Published online Aug 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i8.108959

Revised: May 30, 2025

Accepted: June 30, 2025

Published online: August 27, 2025

Processing time: 120 Days and 4.4 Hours

Complex hepatolithiasis has a high perioperative risk and recurrence rate. Cur

We present the case of a woman with intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile duct stones and chronic cholangitis who underwent laparoscopic hepatectomy. He

Based on segmental/subsegmental diseased bile duct tree territory hepatectomy and hilar stenosis relief, laparoscopic hepatectomy for complex hepatolithiasis can be safely performed guided by double landmarks (diseased bile duct/hepatic vein).

Core Tip: This study describes the complex case of a woman with intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile duct stones and chronic cholangitis who underwent laparoscopic hepatectomy. Laparoscopic hepatectomy for complex hepatolithiasis can be safely performed using double landmarks (diseased bile duct/hepatic vein).

- Citation: Yang YH, Li XJ, Liu YX, Wang XR, Li JW. Laparoscopic hepatectomy based on diseased bile duct tree territory guided by double landmarks for hepatolithiasis: A case report. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(8): 108959

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i8/108959.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i8.108959

The surgical management of complex hepatolithiasis poses considerable challenges due to the intricate anatomical variations of the biliary system, significant perioperative risks, and unfavorable long-term outcomes including high recurrence and reoperation rates. Multiple surgical interventions often lead to severe complications such as intra-abdominal infections, biliary fistulae (including biliary-enteric and biliary-bronchial variants), and iatrogenic bile duct injuries. Patients with a history of repeated biliary surgeries, including cholangioplasty or bile duct repair, frequently require reoperative laparotomy, which further increases technical difficulty and postoperative morbidity. Due to the increasing progress in laparoscopic technology, increased understanding of disease pathophysiology and liver anatomy, and continuous sublimation of surgical concepts, the safety of laparoscopic hepatectomy for complex hepatolithiasis has been widely recognized. Laparoscopic hepatectomy results in minimal trauma and rapid recovery. Compared to open surgery, laparoscopic hepatectomy for complex hepatolithiasis results in lower complication rates and comparable operative times, residual stone rates, and recurrence rates[1,2]. However, standardized treatment protocols and reliable anatomical landmarks remain undefined, we propose surgical planning and operative procedures for complete resection of the dilated bile duct tree guided by double landmarks (diseased bile duct/hepatic vein) and full resolution of the hilar bile duct stricture as a possible standardized treatment for complex hepatolithiasis.

The 56-year-old female patient was admitted to the hospital due to recurrent epigastric pain with chills and fever for 5 years, aggravated for 1 day.

The patient reported abdominal pain with jaundice, and the stool was clay-like in color.

She had a history of open gallbladder resection and biliary tract exploration stone removal 7 years ago.

She also had a family history of hepatolithiasis.

On examination, her body temperature was 38.8 °C, with a pulse rate of 96 beats per minute and blood pressure measuring 96/52 mmHg. There was evidence of jaundice in the skin and sclera. The incision on the rectus abdominis muscle in the right upper quadrant measured approximately 11 cm in length, accompanied by epigastric tenderness, rebound tenderness, and mild muscle rigidity.

The post-hospitalization laboratory results are summarized as follows: The white blood cell, red blood cell, and platelet counts in addition to tumor markers were all normal. Total bilirubin level was 137 μmol/L, direct bilirubin level was 76 μmol/L, indirect bilirubin level was 61 μmol/L and gamma-glutamyl transferase level was 651 U/L. Liver function was classified as grade A, and performance status score was 0.

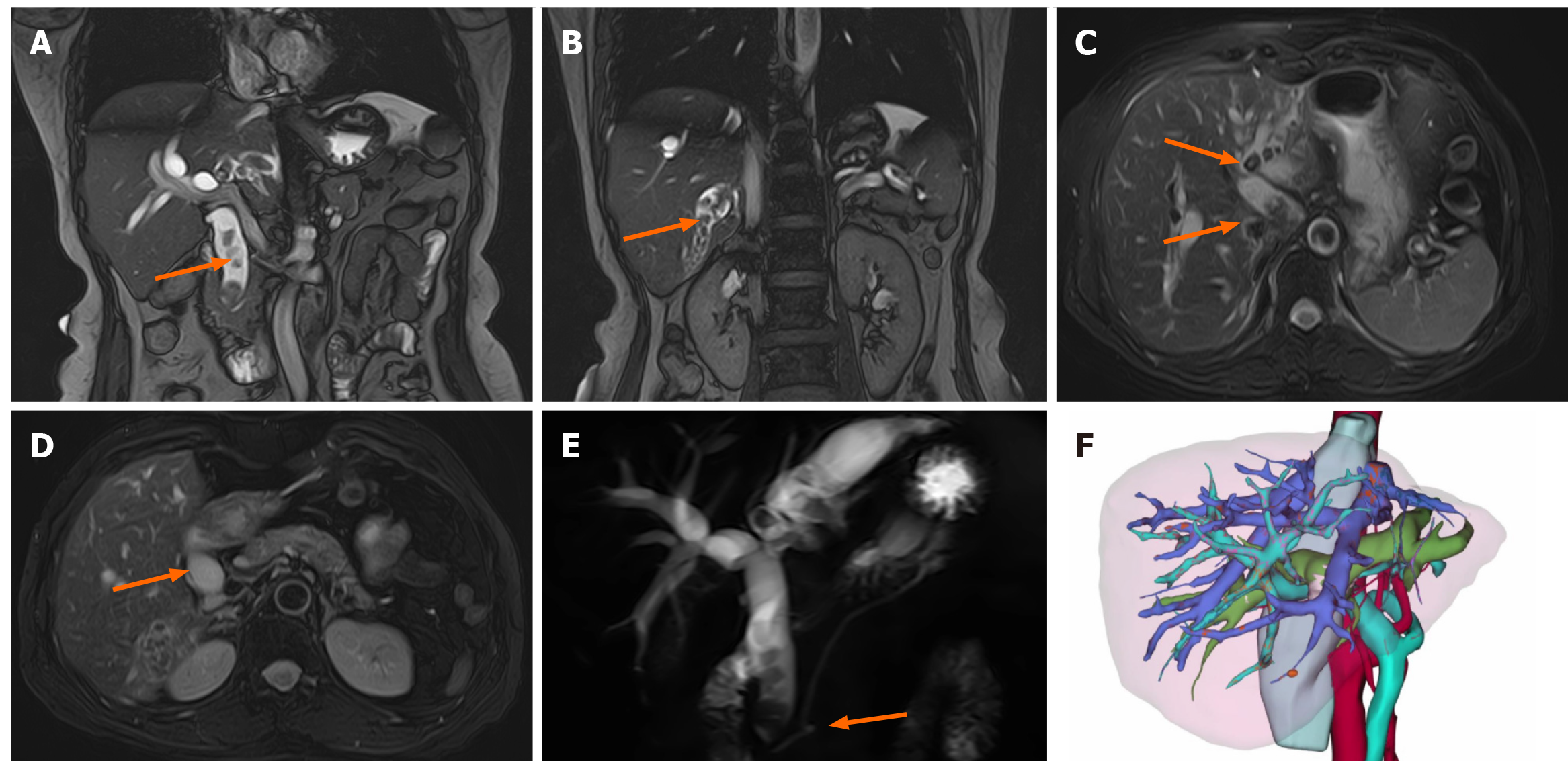

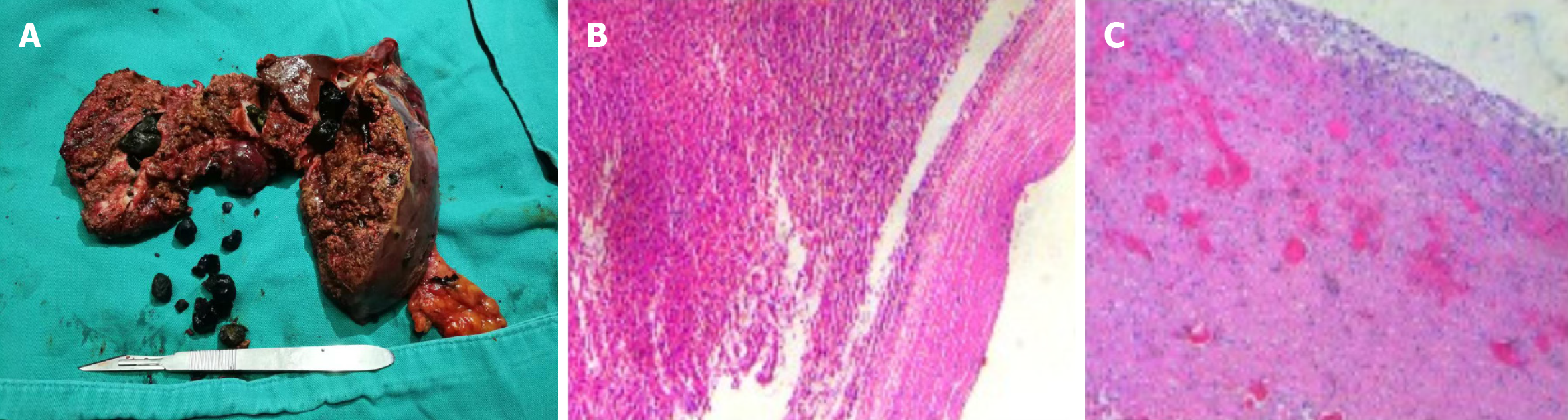

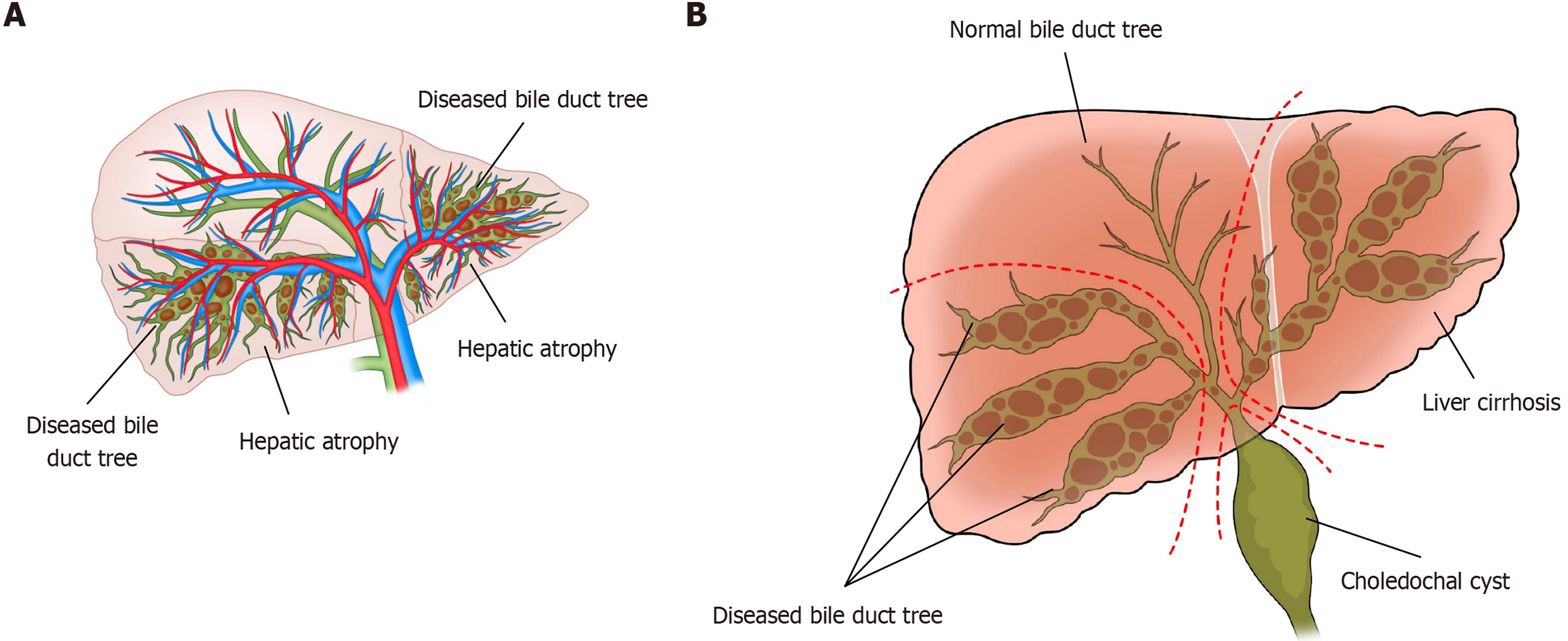

The patient was hospitalized for a comprehensive diagnostic workup, which involved contrast-enhanced abdominal magnetic resonance imaging, abdominal computed tomography (CT) with contrast enhancement, and three-dimensional image reconstruction (Figure 1). The diagnostic imaging findings, supported by histopathological analysis, verified the presence of hepatolithiasis complicated by biliary tract inflammation and cystic dilatation of the common bile duct (Figure 2).

The patient was diagnosed with intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile duct stones and chronic cholangitis with a common bile duct cyst.

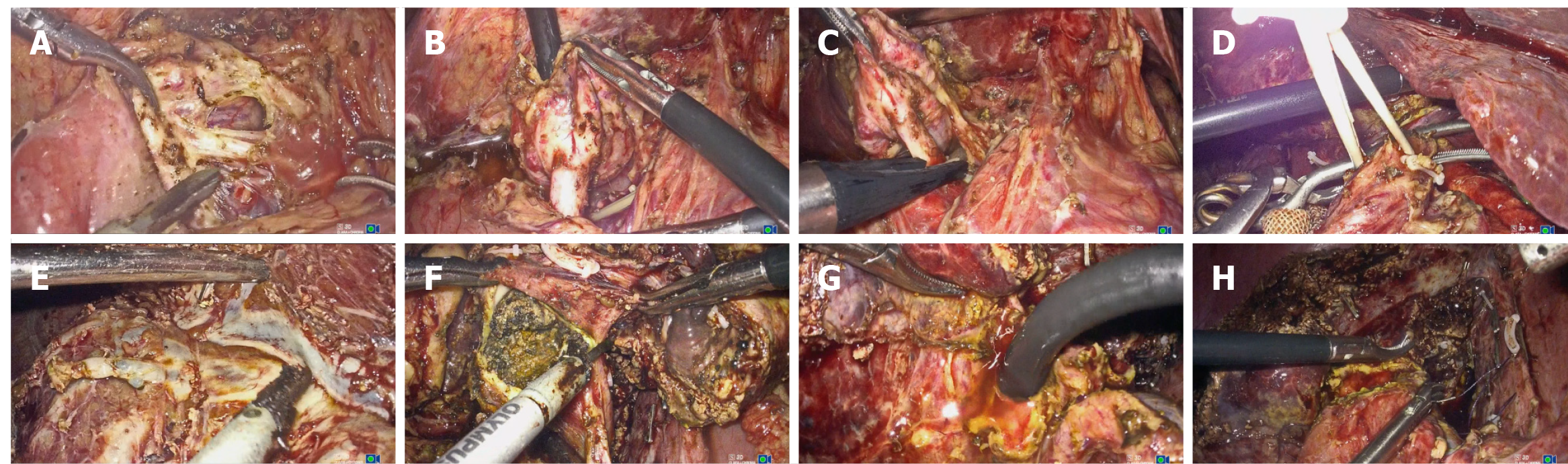

In accordance with the preoperative surgical planning, anatomical resection of liver segments I, II, III, IV, VI, and VII was performed to completely remove the pathological bile duct territories. This was followed by meticulous hilar bile duct reconstruction with Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy to restore biliary-enteric continuity. Abdominal exploration demonstrated no evidence of malignant transformation or metastatic disease. The choledochal cyst was then completely excised through a systematic dissection extending from the cyst dome to the hepatic hilum superiorly and continuing distally to the pancreatic portion of the common bile duct. Meticulous choledochoscopic evaluation of the distal common bile duct was performed, including saline irrigation to ensure complete stone clearance and minimize the risk of postoperative pancreatitis. The hepatic portal plate was dissociated, and the left branch and right posterior branch of the portal vein and hepatic artery were dissected following determination of the right anterior branch of the portal vein. The short veins of the severed liver and portal vein branch supplying the caudate lobe were carefully separated. The liver surface was dissected along the ischemic line demarcated by the dilated bile duct tree. The caudate and atrophied right posterior lobe were completely removed along the right hepatic vein and dilated right posterior bile duct, and pulled to the left side. After the left hepatic vein was disconnected using a stapling system, the liver was gradually severed along the middle hepatic vein from the cranial side to the caudal side. Liver segments I, II, III, IV, VI, and VII were completely removed and specimens were collected. The narrow bile duct in the hilum was formed into a spacious opening, and a bile duct jejunal anastomosis was completed by continuous suturing of the intestinal loop with absorbable thread (Figure 3).

The operating time was 400 minutes, and the intraoperative blood loss was 300 mL. The drainage tube was removed after CT of the chest and abdomen on postoperative day 7. The patient was discharged without complications on postoperative day 9. Stone recurrence and anastomotic stenosis were not observed during the 2-year follow-up. Important indicators of liver function were strictly followed up during the perioperative period (Figure 4).

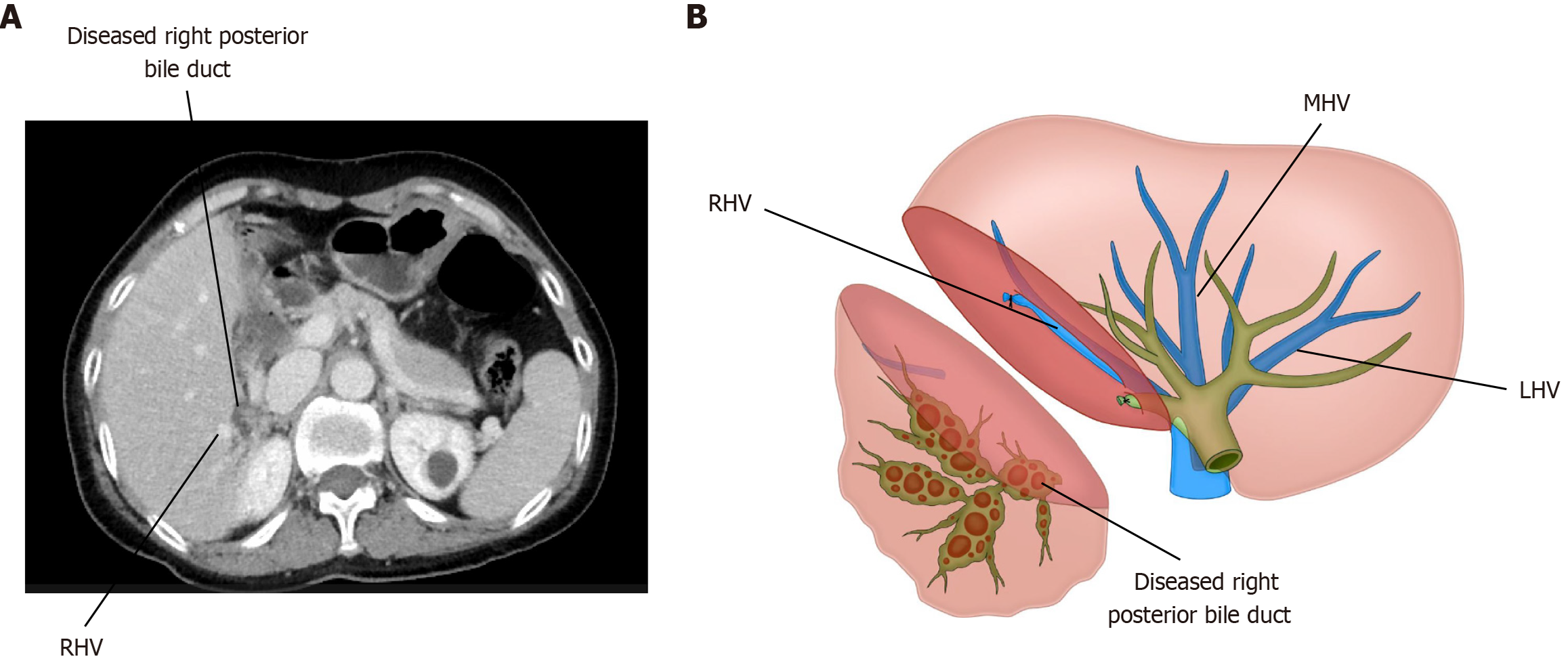

Anatomical hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma comprises complete liver resection of the responsible territory (or territories) of the portal venous branches[3]. In anatomical liver resection, the hepatic vein-guided approach also represents a safe and effective strategy[4]. Most of the diseased livers and portal veins in patients with hepatolithiasis are atrophied[5], with only the remaining dilated bile ducts and stones, which are often close to the iconic hepatic veins (Figure 5). The portal vein, artery, and bile duct walk in the same connective tissue-wrapped Glisson pedicle, and the area of bile duct drainage is, in most cases, equivalent to the area of portal vein drainage (Figure 6A). For biliary diseases, especially hepatolithiasis, anatomical resection should focus on segmental/subsegmental diseased bile duct tree territory hepatectomy as the core as well as the removal of hepatic hilar stenosis to eradicate stones, achieve unobstructed bile drainage, and prevent recurrence[5] (Figure 6B). Finding the correct transection plane has always been a difficult step in surgery. A major challenge in hepatolithiasis surgery is determining the correct transection plane due to hepatic atrophy and anatomical distortion. Due to atrophy and occlusion of the portal vein, dilated bile ducts and hepatic veins become specific anatomical landmarks, and can guide the transection plane of liver dissection. Observing the gap between the two landmarks can ensure that the direction of liver disconnection is not lost in these patients.

Hepatolithiasis, stone irritation, biliary tract infection, and other factors lead to hyperplasia of the bile duct fibers and connective tissue, localized thickening of the bile duct wall, and thinning of the bile duct lumen. More than one-third of patients experience hilar bile duct stenosis. In this case, to fully resolve the stenosis of the hilar bile duct, the total caudate lobe was resected to avoid the retention of multiple small bile ducts, which reduced the incidence of postoperative bile leakage. The total caudal lobe only accounts for 8%-12% of the total liver volume. Combined resection of the total caudal lobe does not increase postoperative liver failure secondary to excessive loss of liver tissue. Additionally, in the presented case, the patient was concurrently diagnosed with a choledochal cyst. Imaging studies further revealed the presence of a pancreaticobiliary maljunction, which may have contributed to the pathogenesis of the choledochal cyst and the development/progression of intrahepatic bile duct stones.

Based on segmental/subsegmental diseased bile duct tree territory hepatectomy and hilar stenosis relief, laparoscopic hepatectomy can be safely performed guided by double landmarks (diseased bile duct/hepatic vein) for complex hepatolithiasis. Prospective, large-sample, multicenter, randomized studies are needed to confirm this concept and establish a standard laparoscopic technique for complex hepatolithiasis.

| 1. | Liu X, Min X, Ma Z, He X, Du Z. Laparoscopic hepatectomy produces better outcomes for hepatolithiasis than open hepatectomy: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2018;51:151-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Li H, Zheng J, Cai JY, Li SH, Zhang JB, Wang XM, Chen GH, Yang Y, Wang GS. Laparoscopic VS open hepatectomy for hepatolithiasis: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:7791-7806. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Wakabayashi T, Benedetti Cacciaguerra A, Ciria R, Ariizumi S, Durán M, Golse N, Ogiso S, Abe Y, Aoki T, Hatano E, Itano O, Sakamoto Y, Yoshizumi T, Yamamoto M, Wakabayashi G; Study Group of Precision Anatomy for Minimally Invasive Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic surgery (PAM-HBP surgery). Landmarks to identify segmental borders of the liver: A review prepared for PAM-HBP expert consensus meeting 2021. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2022;29:82-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yu DC, Wu XY, Sun XT, Ding YT. Glissonian approach combined with major hepatic vein first for laparoscopic anatomic hepatectomy. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2018;17:316-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Huang L, Lai J, Liao C, Wang D, Wang Y, Tian Y, Chen S. Classification of left-side hepatolithiasis for laparoscopic middle hepatic vein-guided anatomical hemihepatectomy combined with transhepatic duct lithotomy. Surg Endosc. 2023;37:5737-5751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |