Published online Jun 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i6.104729

Revised: March 27, 2025

Accepted: May 9, 2025

Published online: June 27, 2025

Processing time: 151 Days and 9.4 Hours

Post-hepatectomy portal vein thrombosis (PH-PVT) is a life-threatening com

To examine the incidence, risk factors, and outcomes associated with PH-PVT.

Medical records of patients who underwent hepatic resection for various diseases between February 2014 and December 2023 at Beijing Tsinghua Changgung Hospital affiliated with Tsinghua University (Beijing, China) were retrospectively reviewed. The patients were divided into a PH-PVT group and a non-PH-PVT group. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to identify the risk factors for PH-PVT.

A total of 1064 patients were included in the study cohort, and the incidence and mortality rates of PH-PVT were 3.9% and 35.7%, respectively. The median time from hepatectomy to the diagnosis of PH-PVT was 6 days. Multivariate analysis revealed that hepatectomy combined with pancreaticoduodenectomy (HPD) [odds ratio (OR) = 7.627 (1.390-41.842), P = 0.019], portal vein reconstruction [OR = 6.119 (2.636-14.203), P < 0.001] and a postoperative portal vein angle < 100° [OR = 2.457 (1.131-5.348), P = 0.023] were independent risk factors for PH-PVT. Age ≥ 60 years [OR = 8.688 (1.774-42.539), P = 0.008] and portal vein reconstruction [OR = 6.182 (1.246-30.687), P = 0.026] were independent risk factors for mortality in PH-PVT patients.

Portal vein reconstruction, a postoperative portal vein angle < 100° and HPD were independent risk factors for PH-PVT. Age ≥ 60 years and portal vein reconstruction were independent risk factors for mortality in PH-PVT patients.

Core Tip: This retrospective study included 1064 patients who underwent hepatectomy to investigate the incidence, risk factors, and outcomes associated with post-hepatectomy portal vein thrombosis (PH-PVT). This study meticulously examined the risk factors contributing to PH-PVT, with an aim of guiding clinicians in recognizing and preventing its occurrence. Furthermore, this study (for the first time) analyzed the mortality risk factors for PH-PVT to provide invaluable insights for the effective management of affected patients.

- Citation: Song JP, Xiao M, Ma JM, Zhang S, Yang LQ, Wang ZS, Xiang CH. Incidence, risk factors and outcomes for post-hepatectomy portal vein thrombosis: A retrospective study. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(6): 104729

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i6/104729.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i6.104729

Hepatectomy, a widely conducted surgical intervention for the treatment of hepatic neoplasms and metastatic lesions[1,2], is progressively being incorporated into the management of both benign and malignant conditions[3]. Despite remarkable advancements in surgical techniques and perioperative care, hepatectomy still presents a substantial risk of morbidity and mortality[4,5], with certain rare, yet critical, complications often overlooked by clinicians, leading to dire consequences. Post-hepatectomy portal vein thrombosis (PH-PVT) is a potentially fatal complication that has historically been underappreciated in clinical practice.

PH-PVT denotes the formation of thrombi within the portal vein and its primary tributaries following hepatectomy. This perilous complication possesses the potential to diminish hepatic portal flow, ultimately leading to hepatic insufficiency. Should the thrombosis extend into the branches of the portal vein, such as the superior mesenteric vein (SMV), mesenteric ischemia may ensue. Previous studies have reported varying morbidity estimates associated with PH-PVT, ranging from 0.9% to 14.3%[6-11]. Factors such as right hepatectomy, prolonged operative duration, extended Pringle maneuver time, caudate lobectomy, postoperative biliary leakage, portal vein segmental resection, and variations in the portal vein’s angle and diameter have been linked to the occurrence of PH-PVT[7-9,12-14]. However, these studies exhibit several limitations, including small sample sizes, a focus on a singular disease type, and the constraints of single-center designs, resulting in inconsistent findings. Consequently, the precise risk factors for PH-PVT remain uncertain.

In this study, we gathered clinical data from 1064 patients who underwent hepatic resection for a range of conditions, including benign disorders, biliary tract cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), and other malignant diseases. The data were obtained from Beijing Tsinghua Changgung Hospital, a distinguished institution affiliated with Tsinghua University, renowned for its expertise in managing complex hepatobiliary conditions. We then performed a retrospective analysis to assess the incidence, risk factors, diagnostic methods, preventive strategies, treatment options, and clinical outcomes related to PH-PVT.

A total of 1064 patients who underwent hepatic resection for various diseases and were admitted to Beijing Tsinghua Changgung Hospital, affiliated with Tsinghua University (Beijing, China), between February 2014 and December 2023, with complete clinical data, were retrospectively analyzed. Based on the development of portal vein thrombosis after hepatectomy, the patients were divided into a PH-PVT group and a non-PH-PVT group. This study received approval from the Research Ethics Board of Beijing Tsinghua Changgung Hospital (No. 23612-6-01).

All patients underwent comprehensive preoperative evaluations. The preoperative factors assessed included sex, age, body mass index, underlying conditions, and liver cirrhosis. Hepatic fibrosis was confirmed through histopathological examination following the surgical procedure. Key blood biochemical markers, including platelet count, prothrombin time-international normalized ratio (PTINR), fibrinogen degradation product (FDP), and D-dimer, were measured. The preoperative laboratory results were sourced from the most recent tests conducted prior to hepatectomy. Additionally, all patients underwent four-phase contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT).

The choice of surgical procedure was based on the following criteria: A major hepatectomy involved the resection of three or more liver segments, while all other hepatectomies were classified as minor hepatectomies. Additionally, the maximum extent of liver resection was determined by the indocyanine green retention rate at 15 minutes. To manage hepatic inflow, the Pringle maneuver was performed. For hepatic parenchymal transection, an ultrasonic dissector (CUSA; Integra Lifesciences, Plainsboro, NJ, United States) was utilized. Hem-o-lok clips were used to ligate small vessels, while EnSeal devices were employed to seal larger vessels, including Glissonian pedicles.

The surgical factors considered included the type of procedure performed, the extent of liver resection, the duration of surgery, blood loss, the total duration of the Pringle maneuver, and any concurrent organ resections, among other relevant factors.

All patients were initially admitted to the intensive care unit, where a contrast-enhanced CT scan of the abdomen was routinely performed on approximately the fifth postoperative day, or earlier if clinically indicated by laboratory results or clinical observations. Hematological analyses were conducted on the first postoperative day and then every two days thereafter. The three-dimensional (3D) images of the portal venous system, hepatic portal vein, and the main PV in particular were reconstructed using a 3D workstation (IQQA-3D, EDDA Technology, Princeton, NJ, United States). The remnant portal vein was defined as an extrahepatic portion of the PV of the remnant liver after liver resection. The postoperative diameters and postoperative angles of the main portal vein (MPV) and remnant portal vein were also measured by rotating 3D images (for patients undergoing major hepatectomy).

Post-hepatectomy thrombosis was defined as the presence of thrombosis within the portal vein and its associated branches, such as the SMV, as identified through postoperative imaging. Hepatic blood flow was monitored daily during the perioperative period using color Doppler ultrasound. In instances where a reduction in portal vein flow or thrombus formation was detected via color Doppler ultrasound, a contrast-enhanced CT scan was performed to confirm the diagnosis. Contrast-enhanced CT was also employed when color Doppler ultrasound failed to detect PH-PVT and the patient exhibited symptoms such as fever, abdominal pain, persistent ascites, or hepatic dysfunction following hepatectomy. Radiologists meticulously examined the CT images, diagnosed PH-PVT, and precisely located the thrombosis. MPV thrombosis was defined as a thrombus confined to the portal vein trunk or extending into the SMV. Peripheral portal vein (PPV) thrombosis was characterized by a thrombus located within the portal vein stump or its branching vessels.

All patients diagnosed with PH-PVT were treated with anticoagulation therapy, provided there were no contraindications. In cases where portal vein blood flow did not improve despite anticoagulant treatment, thrombolysis or surgical thrombectomy procedures were performed, followed by continued anticoagulation therapy.

Upon completion of the treatment, a contrast-enhanced CT scan was conducted to assess the restoration of unob

The variables included in this study encompassed clinicopathological factors potentially associated with PH-PVT, such as the patients’ general information, surgical-related factors, and the results of preoperative and postoperative laboratory examinations. We conducted a retrospective comparison of clinicopathological factors between patients with PH-PVT (PH-PVT group) and those without PH-PVT (non-PH-PVT group). Patients with preexisting portal vein thrombus prior to hepatectomy were excluded from the study.

Numerical variables are presented as medians and interquartile ranges. For numerical variables, when the data met the normal distribution and variance homogeneity test requirements, the t test was used for the comparison between the two groups. If the data were not normally distributed, the Wilcoxon test was used for the comparison between the two groups. For classification types of variables, when the data met the conditions of a theoretical frequency > 5 and a total number of samples ≥ 40, the χ2 test was used for the intergroup comparisons; in contrast, when the data met the conditions of 5 > theoretical frequency ≥ 1 and a total number of samples ≥ 40, the continuous correction χ2 test (Yates’ correction) was used for the intergroup comparisons. When the theoretical frequency of the data was less than 1 or the total number of samples was less than 40, the Fisher’s exact test was used for intergroup comparisons.

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to identify the independent risk factors for PH-PVT and death in patients with PH-PVT. The factors satisfying P values < 0.05 in the comparison test of the two groups were included in the univariate logistic regression analysis, and the factors satisfying P values < 0.05 in the univariate logistic regression analysis were included in the multivariate logistic regression analysis. Furthermore, P values < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 26 and R version 4.2.1 software.

The cohort comprised patients with a variety of hepatobiliary diseases. Of these, 362 patients (34.0%) were diagnosed with biliary tract cancer, including cholangiocarcinoma and gallbladder carcinoma. Additionally, 338 patients (31.8%) had HCC, while 301 patients (28.3%) were diagnosed with benign conditions. Furthermore, 63 patients (5.9%) had other types of malignancies, such as liver metastasis.

The patients enrolled in this study underwent hepatectomy, along with several complex procedures, including portal vein reconstruction. Among the participants, 594 patients (55.8%) underwent major hepatectomy, involving the resection of three or more liver segments, while 470 patients (44.2%) underwent resection of fewer than three liver segments. Furthermore, 226 patients (25.0%) underwent caudate lobectomy, and a small subset of 11 patients (1.0%) underwent hepatectomy combined with pancreaticoduodenectomy (HPD). Additionally, 90 patients (8.5%) underwent portal vein reconstruction, and 9 patients (0.8%) underwent hepatic vein reconstruction. Bile duct resection was performed in 390 patients (36.7%). The median duration of the surgical procedure was 476 minutes. For further details on other clinical aspects, please refer to Table 1.

| Characteristics | Overall (n = 1064) |

| Age | |

| < 60 | 558 (52.4) |

| ≥ 60 | 506 (47.6) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 660 (62) |

| Female | 404 (38) |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 23.24 (21.22, 25.38) |

| Diseases | |

| Biliary tract cancer | 362 (34) |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 338 (31.8) |

| Benign disease | 301 (28.3) |

| Other malignant disease | 63 (5.9) |

| Liver cirrhosis | |

| Yes | 381 (35.8) |

| No | 683 (64.2) |

| Major hepatectomy | |

| Yes | 594 (55.8) |

| No | 470 (44.2) |

| Caudate lobectomy | |

| Yes | 266 (25) |

| No | 798 (75) |

| Pancreaticoduodenectomy | |

| Yes | 11 (1) |

| No | 1053 (99) |

| Portal vein reconstruction | |

| Yes | 90 (8.5) |

| No | 974 (91.5) |

| Hepatic vein reconstruction | |

| Yes | 9 (0.8) |

| No | 1055 (99.2) |

| Bile duct resection | |

| Yes | 390 (36.7) |

| No | 674 (63.3) |

| Operation time (minute), median (IQR) | 476 (328.75, 648) |

| Blood loss (mL), median (IQR) | 300 (100, 500) |

| Blood transfusion | |

| Yes | 516 (48.5) |

| No | 548 (51.5) |

| Postoperative portal vein angle | |

| ≥ 100 | 403 (68.1) |

| < 100 | 189 (31.9) |

| Main portal vein diameter (mm), median (IQR) | 11 (9, 12) |

| Pringle maneuver time (minute), median (IQR) | 56.18 (34.19, 84.27) |

| Preoperative laboratory test | |

| Platelet count (9 × 104/μL), median (IQR) | 195 (145, 260) |

| PTINR, median (IQR) | 1.03 (0.97, 1.09) |

| FDP (μg/mL), median (IQR) | 2.50 (2.50, 2.63) |

| D-dimer (μg/mL), median (IQR) | 0.38 (0.15, 0.88) |

| Postoperative laboratory test | |

| Platelet count (9 × 104/μL), median (IQR) | 157 (110, 209.25) |

| PTINR, median (IQR) | 1.16 (1.08, 1.26) |

| FDP (μg/mL), median (IQR) | 22.46 (13.35, 34.03) |

| D-dimer (μg/mL), median (IQR) | 8.20 (5.72, 13.08) |

In our study cohort, the incidence of PH-PVT was 3.9%, affecting a total of 42 patients. The sex distribution among PH-PVT patients was relatively balanced, with 23 male patients and 19 female patients. The most common underlying disease observed in these cases was biliary tract cancer, particularly perihilar cholangiocarcinoma (PHCC), which accounted for 45.2% of the cases.

Among the types of hepatectomy, 23 patients (54.8%) underwent right hepatectomy or right hepatic trisectionectomy, 15 patients (35.7%) underwent left hepatectomy or left hepatic trisectionectomy, and 4 patients (9.5%) underwent minor hepatectomy. The median time from hepatectomy to confirmatory diagnosis was 6 days. Regarding the location of thrombosis, 37 patients developed MPV thrombosis, while 9 patients developed PPV thrombosis. In patients with MPV thrombosis, the thrombus extended from the MPV to the SMV and splenic vein in 14 patients. Further details of the 42 patients with PH-PVT are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Patients with PH-PVT often present without typical clinical symptoms. The most commonly observed clinical manifestation among these patients was fever (24 patients), while other manifestations included dyspnea and abdominal pain (11 patients), abdominal distension, nausea and vomiting, hematemesis, hematochezia, and jaundice (8 patients). In more severe cases, patients experienced liver failure, hepatic encephalopathy, shock, and even multiple organ failure (13 patients).

The diagnosis of PH-PVT primarily relies on contrast-enhanced CT imaging. Eighteen of our patients underwent color Doppler ultrasonography, and only 8 patients showed positive results.

Among the cohort of 42 patients who developed PH-PVT, 41 individuals received anticoagulation therapy, either alone or in combination with other treatments, while only one patient did not receive any additional intervention. However, the sole administration of anticoagulant therapy proved insufficient for 21 patients. As a result, 10 patients underwent thrombolysis therapy (with one patient requiring reoperation after thrombolysis), and an additional 11 patients underwent reoperation following anticoagulant therapy. Among the five patients who underwent reoperation, two had thrombus suction, while the remaining patients underwent portal vein anastomosis removal and subsequent reconstruction of the portal vein post-thrombectomy. Ultimately, 17 patients experienced resolution, and 10 remained in stable condition; unfortunately, 15 patients succumbed. The causes of mortality among PH-PVT patients included liver failure, coagulation disturbances, septic shock, and multiple organ failure. The treatment modalities and corresponding outcomes for PH-PVT patients are presented in Supplementary Table 1. Additionally, PH-PVT demonstrated a significant mortality rate of 35.7%.

To identify the risk factors associated with PH-PVT, a thorough comparison was made between the clinical characteristics of the PH-PVT group and the non-PH-PVT group. As shown in Table 2, factors such as disease (P = 0.003), major hepatectomy (P < 0.001), caudate lobectomy (P = 0.046), pancreaticoduodenectomy (P < 0.001), portal vein reconstruction (P < 0.001), hepatic vein reconstruction (P = 0.046), bile duct resection (P < 0.001), operation time (P < 0.001), blood loss (P = 0.005), blood transfusion (P = 0.016), postoperative portal vein angle (< 100° vs ≥ 100°, P < 0.001), Pringle maneuver time (P = 0.001), preoperative D-dimer level (P = 0.017), and certain postoperative laboratory test results, such as platelet count (P < 0.001), PTINR (P < 0.001), FDP (P = 0.014), and D-dimer level (P = 0.004), were found to potentially influence the occurrence of PH-PVT. These factors were subsequently included in the univariate logistic regression analysis to screen for risk factors for PH-PVT.

| Characteristics | PH-PVT | Non-PH-PVT | P value | Method |

| n | 42 | 1022 | ||

| Age (n) | 0.534 | χ2 | ||

| < 60 | 24 | 534 | ||

| ≥ 60 | 18 | 488 | ||

| Gender (n) | 0.322 | χ2 | ||

| Male | 23 | 637 | ||

| Female | 19 | 385 | ||

| BMI, median (IQR) | 23.05 (21.70, 25.22) | 23.24 (21.22, 25.39) | 0.944 | Wilcoxon |

| Diseases (n) | 0.003 | Yates’ correction | ||

| Biliary tract cancer | 25 | 337 | ||

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 10 | 328 | ||

| Benign disease | 7 | 294 | ||

| Other malignant disease | 0 | 63 | ||

| Liver cirrhosis (n) | 0.098 | χ2 | ||

| Yes | 10 | 371 | ||

| No | 32 | 651 | ||

| Major hepatectomy (n) | < 0.001 | χ2 | ||

| Yes | 38 | 556 | ||

| No | 4 | 466 | ||

| Caudate lobectomy (n) | 0.046 | χ2 | ||

| Yes | 16 | 250 | ||

| No | 26 | 772 | ||

| Pancreaticoduodenectomy (n) | < 0.001 | Fisher test | ||

| Yes | 6 | 5 | ||

| No | 36 | 1017 | ||

| Portal vein reconstruction (n) | < 0.001 | Yates’ correction | ||

| Yes | 20 | 70 | ||

| No | 22 | 952 | ||

| Hepatic vein reconstruction (n) | 0.046 | Fisher test | ||

| Yes | 2 | 7 | ||

| No | 40 | 1015 | ||

| Bile duct resection (n) | < 0.001 | χ2 | ||

| Yes | 28 | 362 | ||

| No | 14 | 660 | ||

| Operation time (minute), median (IQR) | 667.5 (532.75, 750.75) | 469 (325, 637) | < 0.001 | Wilcoxon |

| Blood loss (mL), median (IQR) | 400 (200, 600) | 250 (100, 500) | 0.005 | Wilcoxon |

| Blood transfusion (n) | 0.016 | χ2 | ||

| Yes | 28 | 488 | ||

| No | 14 | 534 | ||

| Postoperative portal vein angle | < 0.001 | χ2 | ||

| ≥ 100° | 16 | 387 | ||

| < 100° | 22 | 167 | ||

| Main portal vein diameter (mm), median (IQR) | 11 (10, 12) | 11 (9, 12) | 0.147 | Wilcoxon |

| Pringle maneuver time (minute), median (IQR) | 69.69 (58.28, 119.49) | 55 (33.77, 83.90) | 0.001 | Wilcoxon |

| Preoperative laboratory test | ||||

| Platelet count (9 × 104/μL), median (IQR) | 175 (130, 255) | 195 (146, 260) | 0.318 | Wilcoxon |

| PTINR, median (IQR) | 1.02 (0.96, 1.08) | 1.03 (0.97, 1.09) | 0.902 | Wilcoxon |

| FDP (μg/mL), median (IQR) | 2.50 (2.50, 3.68) | 2.50 (2.50, 2.62) | 0.269 | Wilcoxon |

| D-dimer (μg/mL), median (IQR) | 0.56 (0.26, 2.00) | 0.36 (0.15, 0.86) | 0.017 | Wilcoxon |

| Postoperative laboratory test | ||||

| Platelet count (9 × 104/μL), median (IQR) | 113 (83, 168) | 158 (111, 212) | < 0.001 | Wilcoxon |

| PTINR, median (IQR) | 1.24 (1.17, 1.40) | 1.16 (1.08, 1.25) | < 0.001 | Wilcoxon |

| FDP (μg/mL), median (IQR) | 28.74 (21.44, 49.00) | 22.10 (13.15, 33.17) | 0.014 | Wilcoxon |

| D-dimer (μg/mL), median (IQR) | 11.04 (7.23, 16.60) | 8.13 (5.68, 12.80) | 0.004 | Wilcoxon |

As shown in Table 3, several factors were identified as risk factors for PH-PVT, including disease type (biliary tract cancer vs benign disease) [odds ratio (OR) = 3.116 (1.328-7.309), P = 0.009], caudate lobectomy [OR = 1.900 (1.003-3.600), P = 0.049], HPD [OR = 33.900 (9.884-116.268), P < 0.001], portal vein reconstruction [OR = 12.364 (6.43-23.739), P < 0.001], hepatic vein reconstruction [OR = 7.250 (1.459-36.014), P = 0.015], bile duct resection [OR = 3.646 (1.896-7.014), P < 0.001], operation time [OR = 1.003 (1.002-1.004), P < 0.001], blood transfusion [OR = 2.189 (1.139-4.206), P = 0.019], pringle maneuver time [OR = 1.011 (1.005-1.016), P < 0.001], postoperative portal vein angle [< 100° vs ≥ 100°, OR = 3.185 (1.631-6.211), P < 0.001], postoperative platelet count [OR = 0.991 (0.986-0.996), P < 0.001], and PTINR [OR = 1.237 (1.032-1.483), P = 0.022]. Multivariate analysis revealed that HPD [OR = 7.627 (1.390-41.842), P = 0.019], portal vein reconstruction [OR = 6.119 (2.636-14.203), P < 0.001], and postoperative portal vein angle [< 100° vs ≥ 100°, OR = 2.457 (1.131-5.348), P = 0.023] were independent risk factors for PH-PVT.

| Characteristics | n | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

| OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | ||

| Disease | |||||

| Benign disease | 301 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Other malignant disease | 63 | 0.000 (0.000-Infinity) | 0.986 | 0.000 (0.000-Infinity) | 0.987 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 338 | 1.280 (0.481-3.407) | 0.620 | 1.416 (0.402-4.995) | 0.588 |

| Biliary tract cancer | 362 | 3.116 (1.328-7.309) | 0.009 | 1.131 (0.376-3.400) | 0.827 |

| Caudate lobectomy | |||||

| No | 798 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 266 | 1.900 (1.003-3.600) | 0.049 | 0.585 (0.238-1.437) | 0.242 |

| Pancreaticoduodenectomy | |||||

| No | 1053 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 11 | 33.900 (9.884-116.268) | < 0.001 | 7.627 (1.390-41.842) | 0.019 |

| Portal vein reconstruction | |||||

| No | 974 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 90 | 12.364 (6.439-23.739) | < 0.001 | 6.119 (2.636-14.203) | < 0.001 |

| Hepatic vein reconstruction | |||||

| No | 1055 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 9 | 7.250 (1.459-36.014) | 0.015 | 2.314 (0.312-17.180) | 0.412 |

| Bile duct resection | |||||

| No | 674 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 390 | 3.646 (1.896-7.014) | < 0.001 | 1.169 (0.390-3.508) | 0.781 |

| Operation time (minute) | 1064 | 1.003 (1.002-1.004) | < 0.001 | 1.000 (0.997-1.002) | 0.772 |

| Blood loss (mL) | 1064 | 1.000 (1.000-1.001) | 0.238 | ||

| Blood transfusion | |||||

| No | 548 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 516 | 2.189 (1.139-4.206) | 0.019 | 0.627 (0.253-1.549) | 0.311 |

| Pringle maneuver time (minute) | 1060 | 1.011 (1.005-1.016) | < 0.001 | 1.007 (0.998-1.016) | 0.111 |

| Postoperative portal vein angle | |||||

| ≥ 100° | 403 | Reference | Reference | ||

| < 100° | 189 | 3.185 (1.631-6.211) | < 0.001 | 2.457 (1.131-5.348) | 0.023 |

| Preoperative laboratory test | |||||

| D-dimer (μg/mL) | 1064 | 1.047 (0.951-1.153) | 0.347 | ||

| Postoperative laboratory test | |||||

| Platelet count (9 × 104/μL) | 1064 | 0.991 (0.986-0.996) | < 0.001 | 0.996 (0.990-1.002) | 0.242 |

| PTINR | 1064 | 1.237 (1.032-1.483) | 0.022 | 2.191 (0.826-5.814) | 0.115 |

| D-dimer (μg/mL) | 1064 | 1.027 (0.998-1.057) | 0.071 | ||

| FDP (μg/mL) | 1064 | 1.005 (0.998-1.013) | 0.147 | ||

Furthermore, we further divided the PH-PVT patients into two groups-the death group and the survival group-to analyze the risk factors associated with mortality in PH-PVT patients. The results revealed that age (P = 0.003), disease type (P = 0.028), HPD (P = 0.002), and portal vein reconstruction (P = 0.013) were associated with death in PH-PVT patients (Supplementary Table 2). Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses indicated that age ≥ 60 years [OR = 8.688 (1.774-42.539), P = 0.008] and portal vein reconstruction [OR = 6.182 (1.246-30.687), P = 0.026] were independent risk factors for mortality in PH-PVT patients (Table 4). Additionally, no significant difference was observed in postoperative laboratory indicators between the death group and the survival group, suggesting the absence of effective laboratory markers for predicting the risk of mortality in PH-PVT patients.

| Characteristics | n | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

| OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | ||

| Age | |||||

| < 60 | 24 | Reference | Reference | ||

| ≥ 60 | 18 | 7.857 (1.877-32.896) | 0.005 | 8.688 (1.774-42.539) | 0.008 |

| Disease | |||||

| Benign disease | 7 | Reference | |||

| Biliary tract cancer | 25 | 6.500 (0.680-62.148) | 0.104 | ||

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 10 | 0.667 (0.035-12.839) | 0.788 | ||

| Pancreaticoduodenectomy | |||||

| No | 36 | Reference | |||

| Yes | 6 | 3.47 × 108 (0.000-Infinity) | 0.994 | ||

| Portal vein reconstruction | |||||

| No | 22 | Reference | Reference | ||

| Yes | 20 | 5.500 (1.361-22.223) | 0.017 | 6.182 (1.246-30.687) | 0.026 |

Portal vein thrombus is a rare but severe complication following abdominal surgery. Previous studies have predominantly focused on portal vein thrombus after liver transplantation, splenectomy, and pancreaticoduodenectomy. However, in recent years, there has been increasing clinical interest in PH-PVT. In contrast to other studies[8,9,12], the cohort in this study comprised patients with a diverse range of diseases, including benign conditions, HCC, biliary tract cancer, and other malignant diseases. Furthermore, the patients in this study underwent hepatectomy and multiple complex procedures, including portal vein reconstruction, which provided a more thorough assessment of the incidence and risk factors associated with PH-PVT.

In our study cohort, the incidence rate of PH-PVT was 3.9%, which aligns with the findings of previous studies[6-10]. Interestingly, the most common underlying disease associated with PH-PVT in our cohort was biliary tract cancer (particularly PHCC), which accounted for 45.2% of the cases. This differs from previous studies that identified HCC as the predominant underlying condition in patients with PH-PVT[12]. Han et al[12] reported that, within the PH-PVT patient group, 26.3% of patients were biliary tract cancer. However, in the cohort they recruited, the proportion of biliary tract cancer patients was 11.8%, significantly lower than the 39.9% of HCC patients. The present study included a significant number of patients with complex liver diseases. Among these, the proportion of biliary tract cancer patients was 34%, nearly equivalent to the 31.8% of HCC patients and 28.3% of those with benign liver diseases. The findings of this investigation revealed that biliary tract cancer (specifically PHCC) constituted the largest proportion within the PH-PVT context. This may be attributed to the fact that patients with biliary tract cancer often require extensive hepatectomy, lymph node excision, and frequently need portal vein resection and subsequent reconstruction.

In a study by Kuboki et al[9], the clinical manifestations of PH-PVT were often atypical and nonspecific. Specifically, symptoms such as fever, abdominal distension, and abdominal pain were reported in some patients, while others remained asymptomatic (20%). Furthermore, some patients developed liver failure (32%) and even died (8%). Similarly, Onda et al[10] found that 42% of PH-PVT patients did not exhibit any symptoms after hepatectomy, and the condition was mainly detected via imaging examinations. Takata et al[15] reported that 62% of PH-PVT patients remained asymptomatic after hepatectomy, while 38% of patients experienced PH-PVT-related ascites, graded 1-2 on the Clavien-Dindo scale. Notably, no complications above a Clavien-Dindo grade of 3 were observed. In our study, 23.8% of patients with PH-PVT did not exhibit any symptoms. Among those who did, 57.1% experienced fever, while 19.0% reported symptoms such as abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, hematemesis, and jaundice. Additionally, 31.0% of patients developed liver failure.

In this study, 10 out of 18 patients (55.6%) with PH-PVT had false-negative results on ultrasound, and all patients were ultimately diagnosed using CT scans. The reported sensitivity of ultrasound is approximately 89%, with a specificity of 92%[16]. However, ultrasound sensitivity can be influenced by factors such as prior abdominal surgery, which may obscure the visualization of portal vein thrombus due to the presence of intestinal gas or changes in anatomical position. The sensitivity of detecting PH-PVT using ultrasound alone is only 56%[9]. Nonetheless, ultrasound remains an important tool for the initial screening of PH-PVT. Abdominal enhanced CT has shown improved sensitivity (90%) and specificity (99%) in detecting PH-PVT[17]. Therefore, when PH-PVT is strongly suspected clinically but ultrasound results are inconclusive, immediate enhanced CT is recommended to prevent delays in treatment. Furthermore, previous studies have suggested that a decrease in antithrombin III levels on postoperative day 3 may serve as a predictor for PH-PVT, with a sensitivity of 74% and specificity of 59%[18]. In our study, differences were observed in preoperative D-dimer, postoperative platelet count, PTINR, FDP, and D-dimer results between patients in the PH-PVT group and those in the non-PH-PVT group. However, multivariate analysis revealed that these variables were not independent risk factors for PH-PVT.

Currently, no established guidelines exist for the treatment of PH-PVT. Treatment approaches are primarily based on individualized experiences and aim to eliminate the thrombus to restore vessel patency, prevent thrombus extension, and manage thrombus-related complications. Numerous studies have shown that the majority of PH-PVT patients can be effectively managed with anticoagulant therapy[7,19]. Therefore, if there are no significant contraindications to anticoagulation, immediate initiation of anticoagulant therapy is recommended. It is generally advised that anticoagulant therapy should be continued for at least three months to prevent recurrent thrombosis in partially recanalized portal veins. For patients with a genetic predisposition to thrombosis, anticoagulant therapy may be required for at least six months or even lifelong[20,21]. In cases where simple anticoagulant therapy is ineffective, thrombolytic therapy and early reoperation have proven to be effective treatment options[9,22,23]. In our study, 20 patients received only anticoagulant therapy, with 16 achieving thrombolysis or stability and 4 patients dying. Twenty-one patients received a combination of anticoagulant therapy, thrombolysis, and/or surgery, of whom 10 achieved thrombolysis or stability, and 11 patients died. These findings align with the reported percentage of portal vein recanalization with anticoagulant therapy, which ranges from 24% to 81%[12]. Notably, the optimal treatment approach for PH-PVT should be determined on a case-by-case basis, taking into account factors such as the extent of thrombosis, the presence of complications, and individual patient characteristics. In patients with early MPV thrombosis and significant liver dysfunction, active thrombolysis or surgical intervention should be pursued.

The prognosis of patients with PH-PVT can vary considerably and is influenced by several factors, including the underlying disease, the location and severity of the thrombus, the time from thrombosis formation to diagnosis and treatment, and the chosen treatment approach. The reported mortality rate for PH-PVT ranges from 0% to 12.5%[7-10,12,13]. In our study, the mortality rate among PH-PVT patients was 35.7%, which is notably higher than the rates reported in previous studies. In this cohort, the majority of patients (37 out of 42) had MPV thrombosis. Moreover, in 14 patients, the thrombus extended from the MPV to the SMV and splenic vein, which worsened the impact on liver function and led to poorer clinical outcomes. Currently, no studies have reported the risk factors for mortality in PH-PVT patients. In our study, multivariate analysis identified age and portal vein reconstruction as independent risk factors for mortality in PH-PVT patients. Therefore, in clinical practice, it is essential to maintain heightened awareness and provide adequate attention to elderly patients with PH-PVT and those undergoing portal vein reconstruction.

In addition to other venous thromboses, the pathogenic factors of PH-PVT can be explained by the Virchow triad, which includes blood flow stasis, a hypercoagulable state and vascular endothelial injury; moreover, these factors can coexist and influence each other. Several studies have suggested that genetic defects may contribute to susceptibility to thrombosis, thus leading to PH-PVT when combined with acquired thrombotic stimulators such as liver cirrhosis, pancreatitis, splenectomy, and hepatobiliary surgery[24]. The risk factors for portal thrombosis include right trisectionectomy or right hemihepatectomy[7,9], major hepatectomy[7,10,19], a longer operation time[7,10,25], an operation time of longer than 360[25] or 430[10] minutes, a Pringle maneuver occurring during the operation[7,8,10,12,15], a duration of the Pringle maneuver longer than 75[10] minutes, intraoperative portal vein resection and reconstruction[6,12,13,23], postoperative bile leakage[9,10], liver cirrhosis[10], caudate lobectomy[9], splenectomy[9], bile duct resection[9], HCC[25] and an age older than 70 years[19]. The high incidence of PH-PVT after right hepatectomy is related to the small size and easy sliding of the residual liver after right hepatectomy, which leads to distortion of the portal vein and blood stasis[23]. A postoperative portal vein flow velocity < 15 cm/second is strongly related to the formation of portal vein thrombus, and this velocity parameter represents an independent risk factor for PH-PVT[26,27]. Cao et al[13] reported that a postoperative portal vein angle < 100° and a residual intrahepatic portal vein diameter < 5.77 mm are risk factors for PH-PVT. Similarly, Uchida et al[8] reported that a postoperative portal vein angle < 90° and a diameter ratio of the residual intrahepatic portal vein to the portal vein trunk < 45% are risk factors for the formation of PH-PVT. In our study, we also examined the relationships among the postoperative portal vein angle, MPV diameter, and PH-PVT. Our research identified portal vein reconstruction and a postoperative portal vein angle < 100° as independent risk factors for PH-PVT formation after hepatectomy, which aligns with the findings of previous studies. However, we also highlighted the fact that HPD is an independent risk factor for PH-PVT formation, which has not been previously reported.

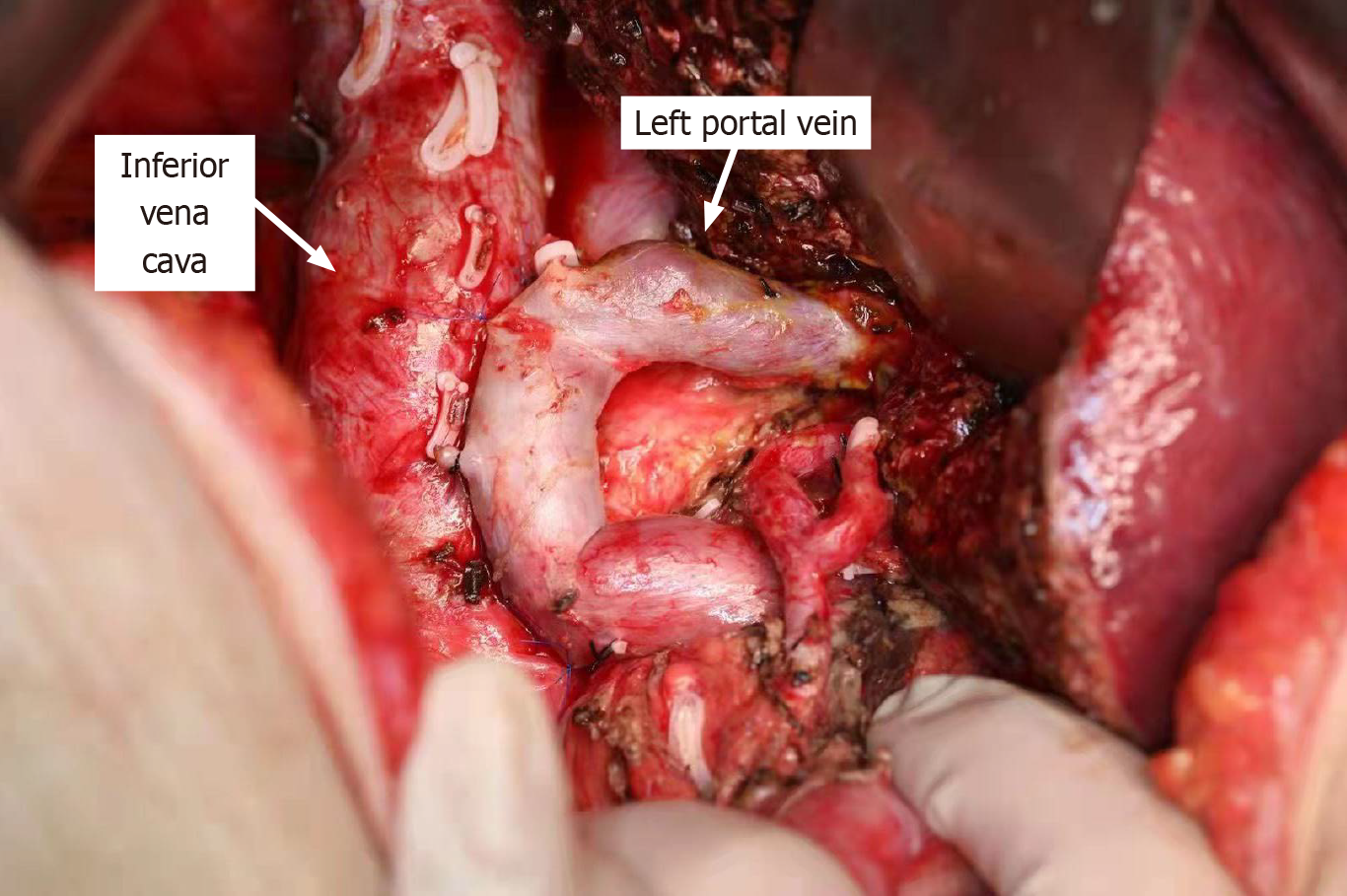

Kuboki et al[9] suggested that suturing of the posterior wall of the portal vein to the anterior wall of the inferior vena cava during surgery can effectively reduce the risk of PH-PVT after right hepatectomy. Following right hepatectomy combined with lymphadenectomy, the portal vein may become redundant, making it more susceptible to angulation and torsion, thereby increasing the risk of PH-PVT. At this stage, it is feasible to employ the technique of placing anchoring sutures between the posterior wall of the portal vein and the anterior wall of the inferior vena cava, thereby caudally stretching the kinked portal vein. This surgical maneuver has the potential to straighten the portal vein and improve portal vein blood flow during right-sided hepatectomy in the absence of portal vein resection. At our research center, we have also implemented this technique in clinical practice to prevent PH-PVT (Figure 1). However, the preventive effect of this method on PH-PVT requires further investigation with larger sample sizes to confirm its efficacy.

However, this study had several limitations. First, it was a retrospective study conducted at a single institution, and the number of postoperative portal vein thrombus events was small. This limited sample size may impact the generalizability of the findings. Second, various anticoagulants were administered in an inconsistent manner, as there are currently no established guidelines for anticoagulant treatment of PH-PVT. Therefore, further research is needed to establish appropriate treatment strategies for PH-PVT following early diagnosis, as this is crucial for improving patient outcomes. Additionally, future studies should focus on the prevention of PH-PVT.

PH-PVT is not an uncommon occurrence and can be a life-threatening complication that demands careful attention. This study is the first to identify HPD as an independent risk factor for PH-PVT. Other independent risk factors for PH-PVT included portal vein reconstruction and a postoperative portal vein angle of < 100°. Furthermore, this study is the first to confirm that age ≥ 60 years and portal vein reconstruction are independent risk factors for mortality in patients with PH-PVT. Among those affected, individuals aged 60 years or older, or those undergoing portal vein reconstruction, are at an increased risk of mortality and should be managed with heightened vigilance in clinical practice.

We are very grateful to Yang LQ from Beijing Tinghua Changgung Hospital for providing statistical consultation for this study.

| 1. | Maehira H, Iida H, Mori H, Nitta N, Maekawa T, Takebayashi K, Kaida S, Miyake T, Tani M. Preoperative Predictive Nomogram Based on Alanine Aminotransferase, Prothrombin Time Activity, and Remnant Liver Proportion (APART Score) to Predict Post-Hepatectomy Liver Failure after Major Hepatectomy. Eur Surg Res. 2023;64:220-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Poon RT, Fan ST, Lo CM, Liu CL, Lam CM, Yuen WK, Yeung C, Wong J. Improving perioperative outcome expands the role of hepatectomy in management of benign and malignant hepatobiliary diseases: analysis of 1222 consecutive patients from a prospective database. Ann Surg. 2004;240:698-708; discussion 708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 495] [Cited by in RCA: 529] [Article Influence: 25.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hyder O, Pulitano C, Firoozmand A, Dodson R, Wolfgang CL, Choti MA, Aldrighetti L, Pawlik TM. A risk model to predict 90-day mortality among patients undergoing hepatic resection. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216:1049-1056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kauffmann R, Fong Y. Post-hepatectomy liver failure. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2014;3:238-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gilg S, Sandström P, Rizell M, Lindell G, Ardnor B, Strömberg C, Isaksson B. The impact of post-hepatectomy liver failure on mortality: a population-based study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:1335-1339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Vivarelli M, Zanello M, Zanfi C, Cucchetti A, Ravaioli M, Del Gaudio M, Cescon M, Lauro A, Montanari E, Grazi GL, Pinna AD. Prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism after resection of hepatocellular carcinoma on cirrhosis: is it necessary? World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:2146-2150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yoshiya S, Shirabe K, Nakagawara H, Soejima Y, Yoshizumi T, Ikegami T, Yamashita Y, Harimoto N, Nishie A, Yamanaka T, Maehara Y. Portal vein thrombosis after hepatectomy. World J Surg. 2014;38:1491-1497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Uchida T, Yamamoto Y, Sugiura T, Okamura Y, Ito T, Ashida R, Ohgi K, Aramaki T, Uesaka K. Prediction of Portal Vein Thrombosis Following Hepatectomy for Perihilar Cholangiocarcinoma: Efficacy of Postoperative Portal Vein Diameter Ratio and Angle. Anticancer Res. 2019;39:5019-5026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kuboki S, Shimizu H, Ohtsuka M, Kato A, Yoshitomi H, Furukawa K, Takayashiki T, Takano S, Okamura D, Suzuki D, Sakai N, Kagawa S, Miyazaki M. Incidence, risk factors, and management options for portal vein thrombosis after hepatectomy: a 14-year, single-center experience. Am J Surg. 2015;210:878-85.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Onda S, Furukawa K, Shirai Y, Hamura R, Horiuchi T, Yasuda J, Shiozaki H, Gocho T, Shiba H, Ikegami T. New classification-oriented treatment strategy for portal vein thrombosis after hepatectomy. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2020;4:701-709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Yoshida N, Yamazaki S, Masamichi M, Okamura Y, Takayama T. Prospective validation to prevent symptomatic portal vein thrombosis after liver resection. World J Hepatol. 2022;14:1016-1024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Han JH, Kim DS, Yu YD, Jung SW, Yoon YI, Jo HS. Analysis of risk factors for portal vein thrombosis after liver resection. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2019;96:230-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cao MT, Higuchi R, Yazawa T, Uemura S, Izumo W, Matsunaga Y, Sato Y, Morita S, Furukawa T, Egawa H, Yamamoto M. Narrowing of the remnant portal vein diameter and decreased portal vein angle are risk factors for portal vein thrombosis after perihilar cholangiocarcinoma surgery. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2021;406:1511-1519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Terasaki F, Ohgi K, Sugiura T, Okamura Y, Ito T, Yamamoto Y, Ashida R, Yamada M, Otsuka S, Aramaki T, Uesaka K. Portal vein thrombosis after right hepatectomy: impact of portal vein resection and morphological changes of the portal vein. HPB (Oxford). 2022;24:1129-1137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Takata H, Hirakata A, Ueda J, Yokoyama T, Maruyama H, Taniai N, Takano R, Haruna T, Makino H, Yoshida H. Prediction of portal vein thrombosis after hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2021;406:781-789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tessler FN, Gehring BJ, Gomes AS, Perrella RR, Ragavendra N, Busuttil RW, Grant EG. Diagnosis of portal vein thrombosis: value of color Doppler imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;157:293-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bach AM, Hann LE, Brown KT, Getrajdman GI, Herman SK, Fong Y, Blumgart LH. Portal vein evaluation with US: comparison to angiography combined with CT arterial portography. Radiology. 1996;201:149-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Okuno M, Kimura Y, Taura K, Nam NH, Li X, Ogiso S, Fukumitsu K, Ishii T, Seo S, Uemoto S. Low level of postoperative plasma antithrombin III is associated with portal vein thrombosis after liver surgery. Surg Today. 2021;51:1343-1351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Mori A, Arimoto A, Hamaguchi Y, Kajiwara M, Nakajima A, Kanaya S. Risk Factors and Outcome of Portal Vein Thrombosis After Laparoscopic and Open Hepatectomy for Primary Liver Cancer: A Single-Center Experience. World J Surg. 2020;44:3093-3099. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Valla DC. Thrombosis and anticoagulation in liver disease. Hepatology. 2008;47:1384-1393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Turnes J, García-Pagán JC, González M, Aracil C, Calleja JL, Ripoll C, Abraldes JG, Bañares R, Villanueva C, Albillos A, Ayuso JR, Gilabert R, Bosch J. Portal hypertension-related complications after acute portal vein thrombosis: impact of early anticoagulation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1412-1417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Thomas RM, Ahmad SA. Management of acute post-operative portal venous thrombosis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:570-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Miyazaki M, Shimizu H, Ohtuka M, Kato A, Yoshitomi H, Furukawa K, Takayashiki T, Kuboki S, Takano S, Suzuki D, Higashihara T. Portal vein thrombosis after reconstruction in 270 consecutive patients with portal vein resections in hepatopancreatobiliary (HPB) surgery. Am J Surg. 2017;214:74-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Janssen HL, Wijnhoud A, Haagsma EB, van Uum SH, van Nieuwkerk CM, Adang RP, Chamuleau RA, van Hattum J, Vleggaar FP, Hansen BE, Rosendaal FR, van Hoek B. Extrahepatic portal vein thrombosis: aetiology and determinants of survival. Gut. 2001;49:720-724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Yamashita Y, Bekki Y, Imai D, Ikegami T, Yoshizumi T, Ikeda T, Kawanaka H, Nishie A, Shirabe K, Maehara Y. Efficacy of postoperative anticoagulation therapy with enoxaparin for portal vein thrombosis after hepatic resection in patients with liver cancer. Thromb Res. 2014;134:826-831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Stine JG, Wang J, Shah PM, Argo CK, Intagliata N, Uflacker A, Caldwell SH, Northup PG. Decreased portal vein velocity is predictive of the development of portal vein thrombosis: A matched case-control study. Liver Int. 2018;38:94-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Zocco MA, Di Stasio E, De Cristofaro R, Novi M, Ainora ME, Ponziani F, Riccardi L, Lancellotti S, Santoliquido A, Flore R, Pompili M, Rapaccini GL, Tondi P, Gasbarrini GB, Landolfi R, Gasbarrini A. Thrombotic risk factors in patients with liver cirrhosis: correlation with MELD scoring system and portal vein thrombosis development. J Hepatol. 2009;51:682-689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 364] [Cited by in RCA: 355] [Article Influence: 22.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |