Published online Oct 27, 2022. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v14.i10.1131

Peer-review started: July 14, 2022

First decision: July 31, 2022

Revised: August 8, 2022

Accepted: September 21, 2022

Article in press: September 21, 2022

Published online: October 27, 2022

Processing time: 102 Days and 21.9 Hours

Thrombectomy and anatomical anastomosis (TAA) has long been considered the optimal approach to portal vein thrombosis (PVT) in liver transplantation (LT). However, TAA and the current approach for non-physiological portal recon

To describe a new choice for reconstructing the portal vein through a posterior pancreatic tunnel (RPVPPT) to address cases of unresectable PVT.

Between August 2019 and August 2021, 245 adult LTs were performed. Forty-five (18.4%) patients were confirmed to have PVT before surgery, among which seven underwent PV reconstruction via the RPVPPT approach. We retrospectively analyzed the surgical procedure and postoperative complications of these seven recipients that underwent PV reconstruction due to PVT.

During the procedure, PVT was found in all the seven cases with significant adhesion to the vascular wall and could not be dissected. The portal vein proximal to the superior mesenteric vein was damaged in one case when attempting thrombolectomy, resulting in massive bleeding. LT was successfully performed in all patients with a mean duration of 585 min (range 491-756 min) and mean intraoperative blood loss of 800 mL (range 500-3000 mL). Postoperative complications consisted of chylous leakage (n = 3), insufficient portal venous flow to the graft (n = 1), intra-abdominal hemorrhage (n = 1), pulmonary infection (n = 1), and perioperative death (n = 1). The remaining six patients survived at 12-17 mo follow-up.

The RPVPPT technique might be a safe and effective surgical procedure during LT for complex PVT. However, follow-up studies with large samples are still warranted due to the relatively small number of cases.

Core Tip: In the study, we presented a new choice for reconstructing the portal vein through a posterior pancreatic tunnel (RPVPPT) to address the issue of unresectable portal vein thrombosis in adult liver transplantation (LT). Clinical data of seven recipients who had portal vein thrombosis (PVT) and underwent RPVPPT were analyzed. PVT was found in all the seven cases with significant adhesion to the vascular wall and could not be dissected. LT was successfully performed in all patients without serious complications. Six patients survived at 12-17 mo follow-up. The RPVPPT technique may be a safe and effective surgical procedure in LT for complex PVT.

- Citation: Zhao D, Huang YM, Liang ZM, Zhang KJ, Fang TS, Yan X, Jin X, Zhang Y, Tang JX, Xie LJ, Zeng XC. Reconstructing the portal vein through a posterior pancreatic tunnel: New choice for portal vein thrombosis during liver transplantation. World J Gastrointest Surg 2022; 14(10): 1131-1140

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v14/i10/1131.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v14.i10.1131

Liver transplantation (LT) remains the mainstay treatment for end-stage liver disease. However, the incidence of portal vein thrombosis (PVT) in patients on the waiting list for transplantation has been reported to range from 5% to 26%. Due to the complexity of treatment techniques, PVT has long been regarded as a contraindication of LT until the 1980s[1-3]. However, the past decade has witnessed unprecedented progress achieved in surgical techniques, leading to the advent of many surgical approaches for recipients with PVT, including physiological portal reconstruction (such as thro

Kasahara et al[13] reported a “pullout technique” for portal vein reconstruction in ten pediatric cases of LT. The portal vein was first pulled out from the back of the pancreas and resected. Then the portal vein reconstruction was completed by bridging the back of the pancreas with allograft or autologous blood vessels. However, this technique has not been widely used, and no relevant reports of its application during adult LT have been documented. Therefore, based on the “pullout technique”, our center explored the technique of reconstructing the portal vein through a posterior pancreatic tunnel (RPVPPT) in adult LT recipients where PVT could not be resolved.

A retrospective analysis was performed on 245 cases of LT at Shenzhen Third People’s Hospital from August 2019 to August 2021. PVT was documented in 45 cases, of which 7 underwent RPVPPT for PVT and portal vein reconstruction (6 males, 1 female; age 48-65 years, mean 54 years). All patients in this study underwent LT with the approval of the Ethics Committee of Shenzhen Third People’s Hospital, and livers were donated after the death of healthy citizens.

Before surgery, each patient underwent Doppler ultrasound and abdominal computed tomography angiography (CTA) to determine the incidence of complications such as PVT. Three-dimensional (3D) visualization models were reconstructed according to the DICOM format data of CTA, as previously described in the literature[14], and surgery was simulated on the model.

Dissection of the hepatic hilum: First, the varicose veins of the hepatic hilum were separated and ligated successively, the common hepatic artery and the proper hepatic artery were dissected, and the left hepatic artery and the right hepatic artery were separated. The main portal vein was dissected from the caudal to the cephalad direction along the trunk to the left and right branches of the portal vein. Finally, the bile duct was isolated and severed near the hilum.

Establishment of the retropancreatic tunnel: First, the main portal vein was dissected from the cephalad to the caudal direction, and the left gastric vein (coronary vein) and the portal vein branch vessels were ligated successively. When the upper edge of the pancreas was reached, dissection started from the lower edge of the pancreas. The superior mesenteric vein (SMV) and splenic vein (SpV) were first separated and lifted with vascular slings. Then, dissection continued from the back of the pancreas to the cephalic side along the main portal vein to establish a retropancreatic tunnel. Subsequently, the pancreas was lifted with a vascular sling or a fine urinary catheter. Finally, the portal vein and its tributary branches behind the pancreas were completely severed and “naked”.

Resection of the main portal vein of the recipient: The severed main portal vein was pulled out from the retropancreatic tunnel to the lower edge of the pancreas. The main portal vein containing the thrombus was removed after interrupting blood flow in the SMV and SpV. If the left gastric vein drained into the SpV or the superior mesenteric-portal vein (SMPV) confluence, it was ligated and severed first to avoid insufficient portal venous flow to the graft due to blood shunting.

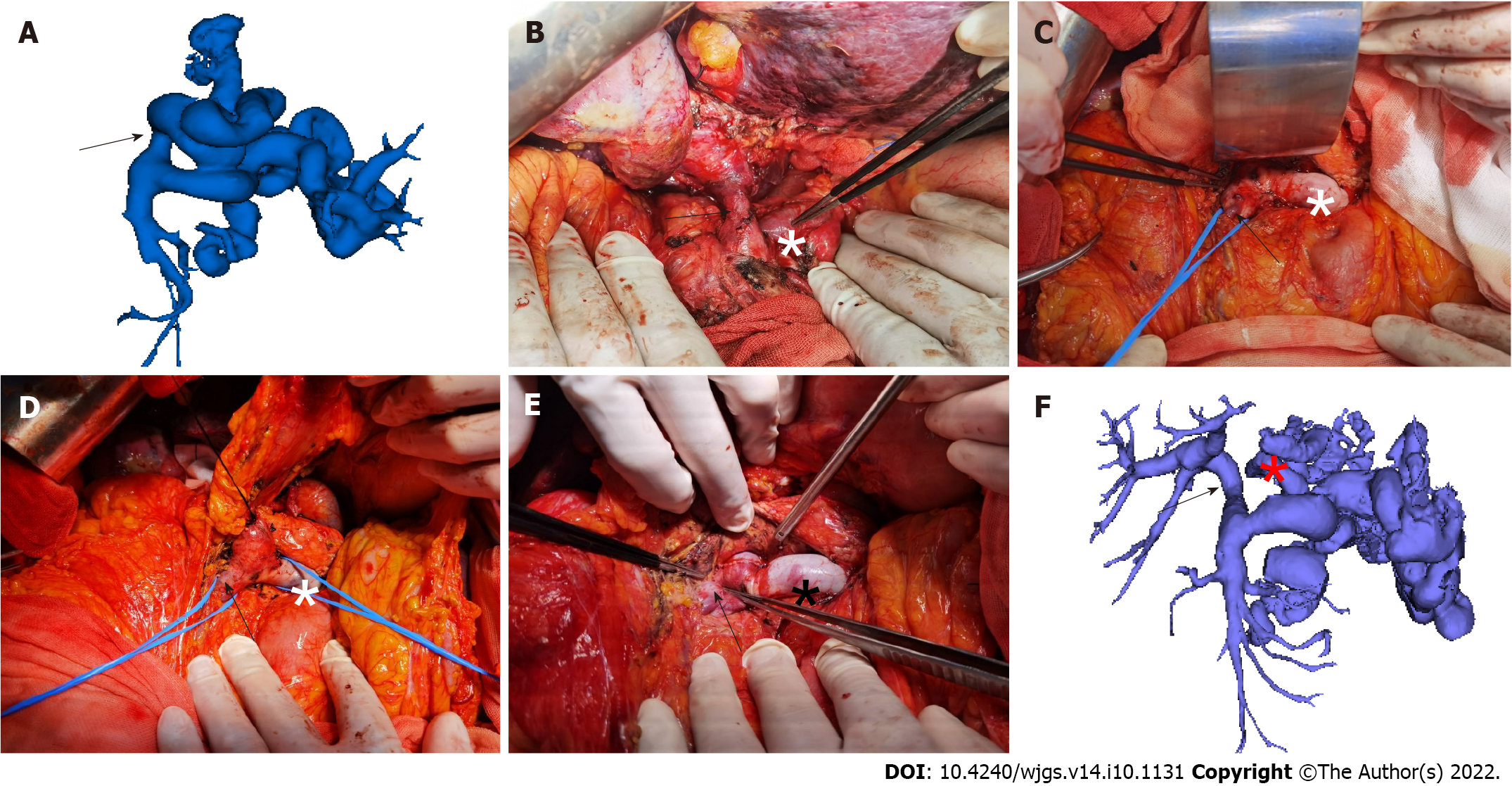

Portal vein reconstruction: After the donor-recipient inferior vena cava anastomosis was completed, the donor’s portal vein was pulled to the lower edge of the pancreas through the retropancreatic tunnel, and the portal vein reconstruction was conducted at the SMPV confluence (Figure 1).

The clinical data of each LT recipient with PVT were collected, including the medical history and laboratory, imaging, and 3D reconstruction results. The surgical methods and operation-related indicators were analyzed, including the operation time, bleeding volume, amount of blood transfusion, and surgical complications.

Patients with PVT included in the present study were cases with a preoperative diagnosis of decompensated hepatitis B virus (HBV)-related cirrhosis (n = 3) and hepatocellular carcinoma with decompensated HBV-related cirrhosis (n = 4). Five cases had a history of gastrointestinal bleeding before the operation. All patients underwent preoperative 3D reconstructions to visually assess blood vessels and simulate surgery, and LT was successfully conducted. The mean operation time was 585 min (range 491-756 min), and the mean intraoperative blood loss was 800 mL (range 500-3000 mL). More details are provided in Table 1.

| Gender | Age | Diagnosis | Operation time (s) | Anhepatic stage (s) | Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | Transfusion of red blood cell suspension (U) | Cold ischemia time (s) | Outcome | |

| Case 1 | Male | 65 | HBV-related decompensated liver cirrhosis, HCC | 648 | 34 | 1300 | 10 | 510 | Survival |

| Case 2 | Male | 48 | HBV-related decompensated liver cirrhosis | 756 | 31 | 1000 | 6 | 480 | Survival |

| Case 3 | Male | 38 | HBV-related decompensated liver cirrhosis | 564 | 35 | 800 | 0 | 390 | Death |

| Case 4 | Female | 64 | HBV-related decompensated liver cirrhosis, HCC | 585 | 25 | 600 | 0 | 360 | Survival |

| Case 5 | Male | 57 | HBV-related decompensated liver cirrhosis, HCC | 583 | 47 | 600 | 0 | 360 | Survival |

| Case 6 | Male | 54 | HBV-related decompensated liver cirrhosis | 491 | 30 | 500 | 0 | 360 | Survival |

| Case 7 | Male | 51 | HBV-related decompensated liver cirrhosis, HCC | 625 | 34 | 3000 | 20 | 360 | Survival |

Anatomical structure of the PVT: One patient presented with complete portal vein occlusion with thrombosis proximal to the SMPV confluence, four cases with portal vein stenosis greater than 70% and thrombosis extending to the SMPV confluence, and two cases with portal vein stenosis greater than 70% and thrombosis extending to the proximal segment of the SMV. All seven patients with PVT presented with organized thrombi that could be completely removed intraoperatively during surgery. Moreover, the proximal portal vein was damaged near the SMPV confluence in one case when attempting thrombolectomy, resulting in massive bleeding.

Anatomical structure of varicose vessels: The left gastric vein drained into the main portal vein (n = 3), SpV (n = 3), and SMPV confluence (n = 1), and the maximum diameter of the left gastric vein was greater than 1 cm in four cases. All cases presented with esophageal and gastric fundal varices and splenorenal shunt; the maximum diameter of the splenorenal shunt was 24 mm, and an umbilical vein opening was found in two cases. More details are provided in Table 2.

| Case | Left gastric vein (coronary vein) | Esophagogastric fundus vein | Superior mesenteric vein | Splenic vein | Shunt situation | ||||||||

| Drain into the main portal vein | Drain into the confluence of SMV and SpV | Drain into SpV | Maximum diameter of the blood vessel (mm) | Degree of varicose veins | History of upper gastrointestinal bleeding | With or without thrombus | Maximum diameter (mm) | With or without thrombus | Maximum diameter (mm) | With or without splenorenal shunt | Maximum diameter of the shunt (mm) | With or without umbilical vein opening | |

| 1 | Yes | 30 | Severe | Yes | No | 18.8 | No | 21.3 | Yes | 21 | No | ||

| 2 | Yes | 10.4 | Severe | Yes | Yes | 17 | No | 14.2 | Yes | 24 | Yes | ||

| 3 | Yes | 24.2 | Severe | Yes | No | 15.4 | No | 12.4 | Yes | 15.7 | No | ||

| 4 | Yes | 13.8 | Severe | Yes | Yes | 10.8 | No | 10.5 | Yes | 17.3 | No | ||

| 5 | Yes | 5.9 | Severe | No | No | 16.4 | No | 12.5 | Yes | 11.2 | Yes | ||

| 6 | Yes | 6.9 | Mild | No | No | 11 | No | 18.4 | Yes | 15.6 | No | ||

| 7 | Yes | 8.2 | Severe | Yes | No | 13.1 | No | 17.1 | Yes | 7.6 | No | ||

Portal vein reconstruction and LT were successfully conducted in all cases, with patent and sufficient portal vein flow documented by intraoperative color Doppler ultrasonography. Six patients recovered smoothly after the surgery, and one patient died. The liver and coagulation function indicators are shown in Tables 3 and 4. Postoperative complications consisted of chylous leakage (n = 3), insufficient portal venous flow to the graft (n = 1), intra-abdominal hemorrhage (n = 1), pulmonary infection (n = 1), and perioperative death (n = 1).

| ALB (g/L) | TB (μmol/L) | DB (μmol/L) | ALT (U/L) | AST (U/L) | GGT (U/L) | PT (s) | INR | |

| Case 1 | 32 | 98 | 52 | 111 | 43 | 78 | 20.4 | 1.72 |

| Case 2 | 31.4 | 11.2 | 4.9 | 49 | 24 | 85 | 16.6 | 1.36 |

| Case 3 | 38.1 | 27.8 | 18.3 | 204 | 63 | 236 | 18.9 | 1.61 |

| Case 4 | 35.1 | 35.1 | 22.8 | 224 | 175 | 741 | 16.4 | 1.30 |

| Case 5 | 35.3 | 39.5 | 23.1 | 169 | 41 | 89 | 15.9 | 1.25 |

| Case 6 | 50 | 26.8 | 14.7 | 329 | 62 | 355 | 14.8 | 1.19 |

| Case 7 | 35 | 20.1 | 13.5 | 48 | 20 | 328 | 15.4 | 1.21 |

| ALB (g/L) | TB (μmol/L) | DB (μmol/L) | ALT (U/L) | AST (U/L) | GGT (U/L) | PT (s) | INR | |

| Case 1 | 33 | 66 | 37 | 58 | 21 | 128 | 17.6 | 1.42 |

| Case 2 | 38.3 | 12.1 | 5.2 | 35 | 15 | 75 | 14 | 1.09 |

| Case 3 | 42.1 | 567 | 226 | 246 | 115 | 232 | 52.2 | 6.0 |

| Case 4 | 34.3 | 80 | 54 | 135 | 87 | 677 | 15.1 | 1.18 |

| Case 5 | 39.1 | 24.2 | 13.2 | 27 | 21 | 39 | 14 | 1.20 |

| Case 6 | 39.8 | 13.8 | 11.2 | 57 | 53 | 140 | 13.6 | 1.12 |

| Case 7 | 34.5 | 13.8 | 8.6 | 37 | 15 | 238 | 14.7 | 1.14 |

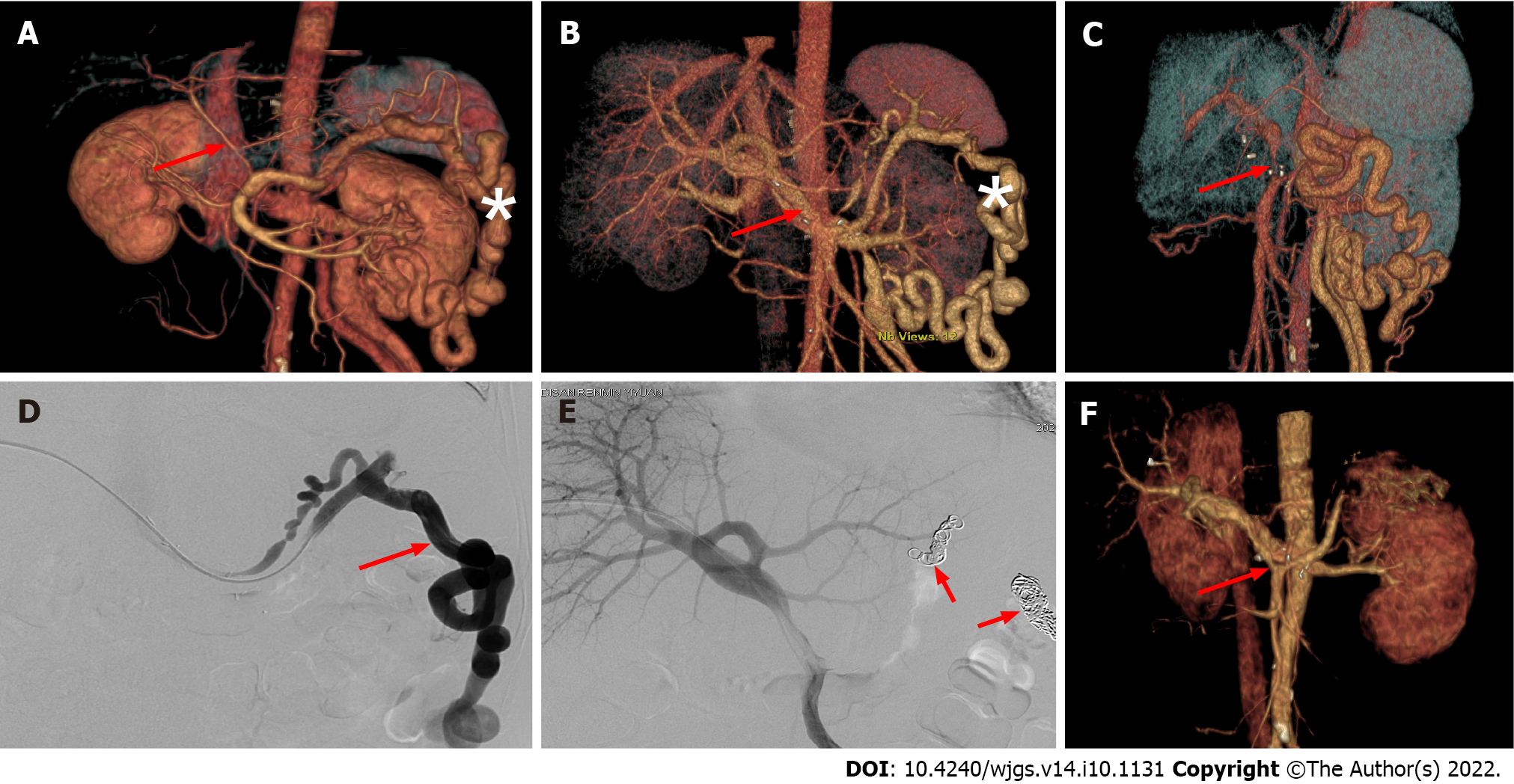

Management of postoperative complications included conservative medical treatment for chylous leaks and antibiotics for pulmonary infection. In cases of insufficient portal venous flow, embolization of splenorenal shunt vessels under digital subtraction angiography (DSA) was used to improve portal venous blood flow (Figure 2). An exploratory laparotomy was performed on a patient with post

PVT refers to thrombosis occurring in the main portal vein and its associated venous system (SMV, inferior mesenteric vein, and SpV). It is one of the most common complications of end-stage liver disease, with an incidence of about 5%-26%[1,15,16]. In the present study, the incidence of PVT was 18.4% (45/245). PVT has long been considered a contraindication for LT due to limited surgical techniques and poor understanding of PVT[17]. With significant inroads achieved in recent years, various innovative surgical approaches are now available.

Hibi et al[10] performed LT in 174 cases of PVT, among which 83 (47.7%) and 91 (52.3%) presented with complete and partial PVT, respectively. In terms of portal vein reconstruction, 149 cases underwent physiological reconstruction [thrombolectomy (n = 123), interposition vein grafts (n = 16), and mesoportal jump grafts (n = 10)]. There were 25 cases of non-physiological reconstruction [cavoportal hemitranspositions (n = 18), renoportal anastomoses (n = 6), and arterialization (n = 1)]. The study found that the non-physiological group suffered a significantly increased incidence of rethrombosis of the portomesenteric veins and gastrointestinal bleeding, with a dismal 10-year overall survival rate of 42% (vs no PVT, 61%; P = 0.002 and vs PVT: Physiological group, 55%; P = 0.043). Rodríguez-Castro et al[12] reported that of 25753 liver transplants, 2004 were performed in patients with PVT (7.78%), and complete thrombosis was observed in nearly 50%. TAA was performed in 75% of patients; other techniques included venous graft interposition and portocaval hemitransposition. It was found that PVT significantly increased post-LT mortality at 30 d (10.5%) and 1 year (18.8%) when compared to patients without PVT (7.7% and 15.4%, respectively). Moreover, rethrombosis occurred in up to 13% of patients with complete PVT, whereby no preventive strategies were used, leading to increased morbidity and mortality. In the present study, there was no recurrence of PVT, but one patient had portal venous insufficiency after LT. Accordingly, the optimal approach for portal vein reconstruction is the restoration of the physiological anatomy of the portal vein system while ensuring adequate portal venous flow[10,18].

At present, no consensus has been reached on the optimal reconstruction approach for different types of PVT during LT. Some scholars have formulated surgical methods according to Yerdel classification criteria[19-21]. However, in some cases, this classification criteria cannot be used to guide clinical practice since the Yerdel standard is based on the extent that the thrombus occupies the portal vein lumen and does not take into account adhesion to the blood vessel wall.

The RPVPPT technique adopted by our team was mainly applied in patients with PVT contraindicated for routine thrombolectomy during the LT surgery. This approach restores the physiological anatomy of the portal vein system while ensuring adequate portal vein blood flow, which is hypothetically ideal for PVT patients. At 12-17 mo follow-up, six of the seven patients survived, preliminarily validating the feasibility and safety of RPVPPT.

However, severe portal hypertension in this patient population accounts for an increase in varicose vessels around the portal vein, or even cavernous transformation of the portal vein, leading to an increased risk of bleeding during the procedure[22,23]. In addition, the RPVPPT technique requires the establishment of a retropancreatic tunnel behind the pancreas in these patients, increasing surgical risks. Accordingly, this surgical approach requires highly skilled surgeons and a transplant team. During the operation, it is recommended to dissect the hepatic hilum along the portal vein to the upper margin of the pancreas and then successively ligate each branch of the portal vein at the lower margin of the pancreas. When separating the lower edge of the pancreas, the SMV and SpV branches should be dissected first, and vascular slings should be placed to lift them for prompt hemostasis during the establishment of the retropancreatic tunnel or the separation of the surrounding tissues of the portal vein. After a successful retropancreatic tunnel is established, lifting the pancreas with a vascular sling or urinary tube is recommended to facilitate portal vein reconstruction (Figure 1).

Intraoperative traction of the pancreas should be as gentle as possible to avoid pancreatic damage and pancreatitis. Based on our experience, we recommend successfully ligating the branches of the blood vessels that merge into the portal vein behind the pancreas. Given that the blood vessels in this region are very thin, hemostasis can be challenging once bleeding occurs. In this regard, given the narrow surgical view, it can be challenging to perform suture hemostasis, and the effect of electrocoagulation is often not satisfactory. In such circumstances, we can only resort to compression hemostasis. In addition, due to the brittleness of pancreatic tissue in patients with portal hypertension and the increase of surface varicose vessels, the risk of hemorrhagic shock is relatively high. Therefore, it is advisable to dissect the lower edge of the pancreas during surgery to prevent postoperative abdominal bleeding. In our study, one patient developed intra-abdominal hemorrhage on postoperative day 7. Exploratory laparotomy revealed that the source of the hemorrhage was at the lower edge of the pancreas, with multiple hemorrhagic foci observed. This finding could be attributed to postoperative pancreatitis since the amylase level in drain fluid from the lower edge of the pancreas was 700 U/L. It is highly likely that the extravasation of pancreatic fluid corroded the blood vessel, thus leading to rupture and bleeding. The patient died of liver failure due to hemorrhagic shock resulting in liver ischemia and hypoxia. Based on our experience, we recommend that the drainage tube should be indwelled at the lower margin of the pancreas and properly fixed. Importantly, the drain fluid amylase level should be assessed regularly after surgery.

During the establishment of the retropancreatic tunnel, the varicose vessels around the portal vein were ligated to create the posterior pancreatic tunnel and reduce the blood shunt of the portal vein system to avoid insufficient portal venous flow to the graft after surgery. However, it is often difficult to ligate splenorenal shunt vascular branches intraoperatively due to their deep location. In some cases, postoperative intervention may be required to manage shunt vessels. In this study, one patient developed insufficient portal venous flow to the graft after surgery, mainly due to significant splenic-renal shunting. DSA showed that most splenic venous flow drained into the inferior vena cava through the shunt rather than the portal vein. After shunt embolization, an immediate improvement in portal vein blood supply was observed.

With the increased number of LT cases, PVT has become a major conundrum that may be solved by portal vein reconstruction. The key point of this technique is to ensure sufficient portal venous blood flow and restore the physiological anatomy of the portal vein system as much as possible. The RPVPPT approach adopted in this study meets the above requirements, and our preliminary assessment yielded good results. We substantiated that the RPVPPT technique is a safe and effective surgical procedure in LT for complex PVT. However, follow-up studies with large samples are warranted due to the relatively small number of cases.

Portal vein thrombosis (PVT) poses a great challenge in liver transplantation (LT). It has been established that thrombectomy and anatomical anastomosis (TAA) can restore the physiological anatomy of the portal vein by complete thrombus excision and has been considered the optimal solution to this problem; however, in some cases, PVT cannot be treated by TAA.

We describe our experience of reconstructing the portal vein through a posterior pancreatic tunnel (RPVPPT) to address the issue of unresectable PVT, which may achieve a similar effect to TAA and provide a new approach to solve this intricate clinical problem.

We sought to describe a new strategy of RPVPPT to address cases of unresectable PVT.

A retrospective analysis was performed on 245 adult patients that underwent LT from August 2019 to August 2021. Forty-five (18.4%) patients presented with PVT before surgery, among which seven underwent portal vein reconstruction using RPVPPT. Preoperative clinical data, operation-related indicators, and postoperative complications were statistically analyzed.

During the operation, PVT was found in all seven cases with significant adhesion to the vascular wall and could not be dissected. LT was successfully performed in all patients without serious postoperative complications. At 12-17 mo follow-up, there were six patients who survived.

The RPVPPT technique can restore the physiological anatomy of the portal vein system through a retropancreatic tunnel, which might be a safe and effective surgical procedure in LT for complex PVT.

Due to the relatively small number of cases in the study, follow-up studies with large samples are still required.

We thank the professor Nan Jiang and the patients for cooperating with our investigation.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Boteon YL, Brazil; Kumar R, India S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Wang JJ

| 1. | Chen H, Turon F, Hernández-Gea V, Fuster J, Garcia-Criado A, Barrufet M, Darnell A, Fondevila C, Garcia-Valdecasas JC, Garcia-Pagán JC. Nontumoral portal vein thrombosis in patients awaiting liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2016;22:352-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ponziani FR, Zocco MA, Senzolo M, Pompili M, Gasbarrini A, Avolio AW. Portal vein thrombosis and liver transplantation: implications for waiting list period, surgical approach, early and late follow-up. Transplant Rev (Orlando). 2014;28:92-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Werner KT, Sando S, Carey EJ, Vargas HE, Byrne TJ, Douglas DD, Harrison ME, Rakela J, Aqel BA. Portal vein thrombosis in patients with end stage liver disease awaiting liver transplantation: outcome of anticoagulation. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:1776-1780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Teng F, Sun KY, Fu ZR. Tailored classification of portal vein thrombosis for liver transplantation: Focus on strategies for portal vein inflow reconstruction. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:2691-2701. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Turon F, Hernández-Gea V, García-Pagán JC. Portal vein thrombosis: yes or no on anticoagulation therapy. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2018;23:250-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lai Q, Spoletini G, Pinheiro RS, Melandro F, Guglielmo N, Lerut J. From portal to splanchnic venous thrombosis: What surgeons should bear in mind. World J Hepatol. 2014;6:549-558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Quintini C, Spaggiari M, Hashimoto K, Aucejo F, Diago T, Fujiki M, Winans C, D'Amico G, Trenti L, Kelly D, Eghtesad B, Miller C. Safety and effectiveness of renoportal bypass in patients with complete portal vein thrombosis: an analysis of 10 patients. Liver Transpl. 2015;21:344-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bhangui P, Lim C, Salloum C, Andreani P, Sebbagh M, Hoti E, Ichai P, Saliba F, Adam R, Castaing D, Azoulay D. Caval inflow to the graft for liver transplantation in patients with diffuse portal vein thrombosis: a 12-year experience. Ann Surg. 2011;254:1008-1016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Borchert DH. Cavoportal hemitransposition for the simultaneous thrombosis of the caval and portal systems - a review of the literature. Ann Hepatol. 2008;7:200-211. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Hibi T, Nishida S, Levi DM, Selvaggi G, Tekin A, Fan J, Ruiz P, Tzakis AG. When and why portal vein thrombosis matters in liver transplantation: a critical audit of 174 cases. Ann Surg. 2014;259:760-766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ghabril M, Agarwal S, Lacerda M, Chalasani N, Kwo P, Tector AJ. Portal Vein Thrombosis Is a Risk Factor for Poor Early Outcomes After Liver Transplantation: Analysis of Risk Factors and Outcomes for Portal Vein Thrombosis in Waitlisted Patients. Transplantation. 2016;100:126-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Rodríguez-Castro KI, Porte RJ, Nadal E, Germani G, Burra P, Senzolo M. Management of nonneoplastic portal vein thrombosis in the setting of liver transplantation: a systematic review. Transplantation. 2012;94:1145-1153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kasahara M, Sasaki K, Uchida H, Hirata Y, Takeda M, Fukuda A, Sakamoto S. Novel technique for pediatric living donor liver transplantation in patients with portal vein obstruction: The "pullout technique". Pediatr Transplant. 2018;22:e13297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zhao D, Lau WY, Zhou W, Yang J, Xiang N, Zeng N, Liu J, Zhu W, Fang C. Impact of three-dimensional visualization technology on surgical strategies in complex hepatic cancer. Biosci Trends. 2018;12:476-483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ponziani FR, Zocco MA, Garcovich M, D'Aversa F, Roccarina D, Gasbarrini A. What we should know about portal vein thrombosis in cirrhotic patients: a changing perspective. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:5014-5020. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Violi F, Corazza GR, Caldwell SH, Perticone F, Gatta A, Angelico M, Farcomeni A, Masotti M, Napoleone L, Vestri A, Raparelli V, Basili S; PRO-LIVER Collaborators. Portal vein thrombosis relevance on liver cirrhosis: Italian Venous Thrombotic Events Registry. Intern Emerg Med. 2016;11:1059-1066. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Shaw BW Jr, Iwatsuki S, Bron K, Starzl TE. Portal vein grafts in hepatic transplantation. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1985;161:66-68. [PubMed] |

| 18. | D'Amico G, Tarantino G, Spaggiari M, Ballarin R, Serra V, Rumpianesi G, Montalti R, De Ruvo N, Cautero N, Begliomini B, Gerunda GE, Di Benedetto F. Multiple ways to manage portal thrombosis during liver transplantation: surgical techniques and outcomes. Transplant Proc. 2013;45:2692-2699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yerdel MA, Gunson B, Mirza D, Karayalçin K, Olliff S, Buckels J, Mayer D, McMaster P, Pirenne J. Portal vein thrombosis in adults undergoing liver transplantation: risk factors, screening, management, and outcome. Transplantation. 2000;69:1873-1881. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 485] [Cited by in RCA: 525] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Nacif LS, Zanini LY, Pinheiro RS, Waisberg DR, Rocha-Santos V, Andraus W, Carrilho FJ, Carneiro-D'Albuquerque L. Portal vein surgical treatment on non-tumoral portal vein thrombosis in liver transplantation: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2021;76:e2184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Rhu J, Choi GS, Kwon CHD, Kim JM, Joh JW. Portal vein thrombosis during liver transplantation: The risk of extra-anatomical portal vein reconstruction. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2020;27:242-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kiyosue H, Ibukuro K, Maruno M, Tanoue S, Hongo N, Mori H. Multidetector CT anatomy of drainage routes of gastric varices: a pictorial review. Radiographics. 2013;33:87-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bosch J, Iwakiri Y. The portal hypertension syndrome: etiology, classification, relevance, and animal models. Hepatol Int. 2018;12:1-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |