Published online Apr 27, 2019. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v11.i4.229

Peer-review started: February 25, 2019

First decision: March 11, 2019

Revised: March 26, 2019

Accepted: April 23, 2019

Article in press: April 23, 2019

Published online: April 27, 2019

Processing time: 61 Days and 12.1 Hours

Hepatocellular adenoma (HCA) is a rare benign liver tumor usually affecting young women with a history of prolonged use of hormonal contraception. Although the majority is asymptomatic, a low proportion may have significant complications such as bleeding or malignancy. Despite responding to the hormonal stimulus, the desire for pregnancy in patients with small HCA is not contraindicated. However, through this work we demonstrate that intensive hormonal therapies such as those used in the treatment of infertility can trigger serious complications

A 33-year-old female with a 10-year history of oral contraceptive use was diagnosed with a hepatic tumor as an incidental finding in an abdominal ultrasound. The patient showed no symptoms and physical examination was unremarkable. Laboratory functional tests were within normal limits and tests for serum tumor markers were negative. An abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed, showing a 30 mm × 29 mm focal lesion in segment VI of the liver compatible with HCA or Focal Nodular Hyperplasia with atypical behavior. After a total of six years of follow-up, the patient underwent ovulation induction treatment for infertility. On a following MRI, a suspected malignancy was warned and hence, surgery was decided. The surgical specimen revealed malignant transformation of HCA towards trabecular hepatocarcinoma with dedifferentiated areas. There was non-evidence of tumor recurrence after three years of clinical and imaging follow-up.

HCAs can be malignant regardless its size and low-risk appearance on MRI when an ovultation induction therapy is indicated.

Core tip: As far as we know, this is the first report of a case involving a young woman with a small hepatocellular adenoma (HCA) with a stable behavior in a 6-year follow-up, who developed imaging changes suggesting malignancy after performing ovulation induction treatment. The patient underwent surgery due to diagnostic uncertainty, and the pathology report confirmed its malignancy. Therefore, we conclude that HCAs can be malignant regardless its size and low-risk appearance on magnetic resonance imaging when a hormone therapy is indicated.

- Citation: Glinka J, Clariá RS, Fratanoni E, Spina J, Mullen E, Ardiles V, Mazza O, Pekolj J, de Santibañes M, de Santibañes E. Malignant transformation of hepatocellular adenoma in a young female patient after ovulation induction fertility treatment: A case report. World J Gastrointestinal Surgery 2019; 11(4): 229-236

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v11/i4/229.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v11.i4.229

Hepatocellular adenoma (HCA) is a rare benign liver tumor that usually affects young women with a history of prolonged use of hormonal contraception[1,2]. Most patients are asymptomatic and diagnosis is made by incidental findings in ultrasonographic studies performed for another reason. A low proportion may have significant complications such as bleeding or malignancy[3]. Therefore, the cessation of hormonal contraception in patients with HCA considered small (less than 5 cm) is usually enough to keep them stable or to cause spontaneous regression[4].

The desire for pregnancy in patients with small HCA is not contraindicated[5]. However, through this work we demonstrate that intensive hormonal therapies such as those used in the treatment of infertility can trigger serious complications. As far as we know, this is the first report of a case involving a young woman with a small HCA with a stable behavior in a 6-year follow-up, that after performing ovulation induction fertility treatment (OIFT) to achieve pregnancy, developed imaging changes that suggested growth and atypical behavior. The patient was offered surgery due to diagnostic uncertainty, and the pathology report confirmed the malignant behavior of the lesion.

The patient was asymptomatic.

The patient had no previous disease.

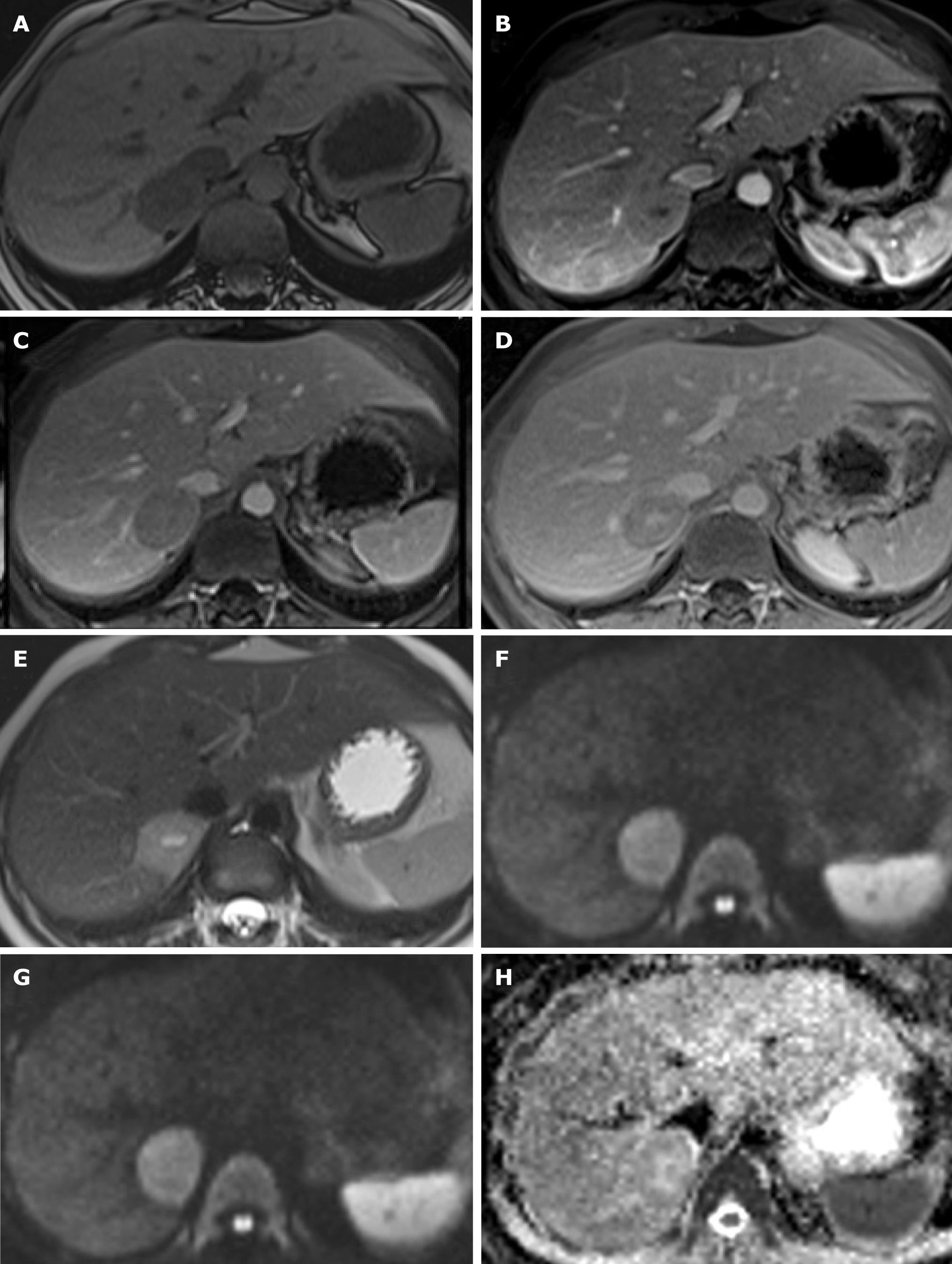

A 33-year-old female with a 10-year history of oral contraceptive use was diagnosed with an hepatic tumor as an incidental finding in an abdominal ultrasound (US). An abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed, showing a 30 mm × 29 mm focal lesion in segment VI of the liver, slightly hyperintense in T2 and isointense in T1 weighted sequences, with a central scar that showed enhancement in early arterial phase and retained contrast on delayed scans, compatible with HCA or Focal Nodular Hyperplasia (FNH) with atypical behavior (Figure 1).

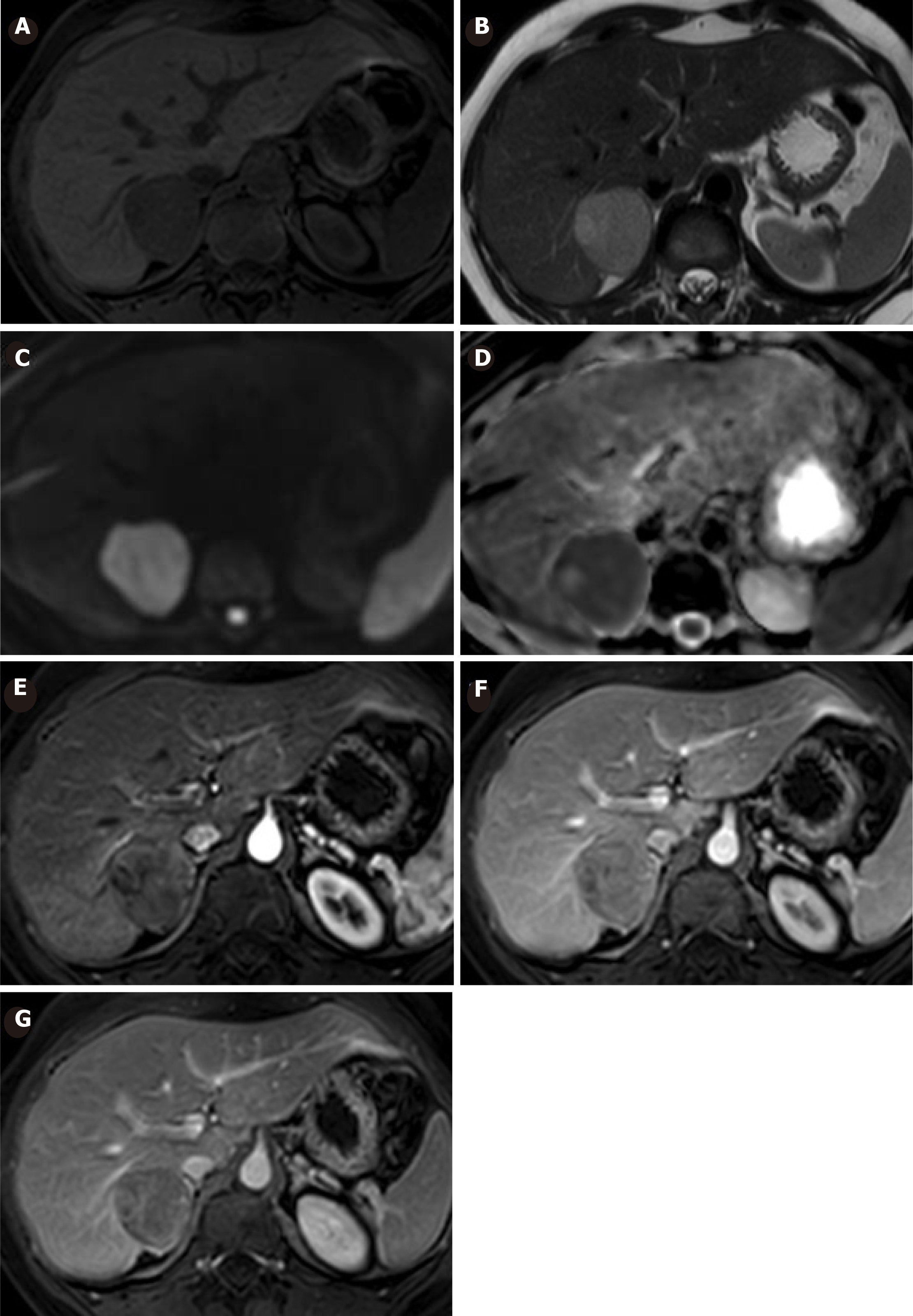

After two years of follow-up, the patient presented an episode of upper quadrant abdominal pain, fever and vomiting. Laboratory test were normal and a new MRI showed a slight reduction in the size of the nodular formation, measuring 26 mm × 18 mm, with a change in its characteristics. Currently showing a hypointense center in T2 and hyperintense appearance in T1, compatible with an intralesional hematic component. The presumptive diagnosis in this circumstance was a HCA with hemorrhagic changes inside (Figure 2).

Because the patient refused to undergo surgery a conservative management was decided, agreeing a strict follow-up with serum tumor markers and color Doppler US alternating with MRI every six months. Since then, no changes in tumor chara-cteristics were observed for the following four years.

The patient later underwent hormonal treatment for infertility. The scheme used consisted in six doses of Clomiphene (50 miligrams/d) the first 6 d, recombinant FSH (follicle-stimulating hormone) 150 IU and LH (luteinizing hormone) 75 IU per day for 10 d. Cetrorelix (0.25 IU) per day during 4 d (from day 6 to 10 from the initiation of the stimulus). Subsequently, HCG (10.000 IU) a single dose in day 11.

Physical examination was unremarkable.

Laboratory functional tests were within normal limits and tests for serum tumor markers carcinoembryonic antigen, carbohydrate antigen 19-9 and alpha-fetoprotein were negative.

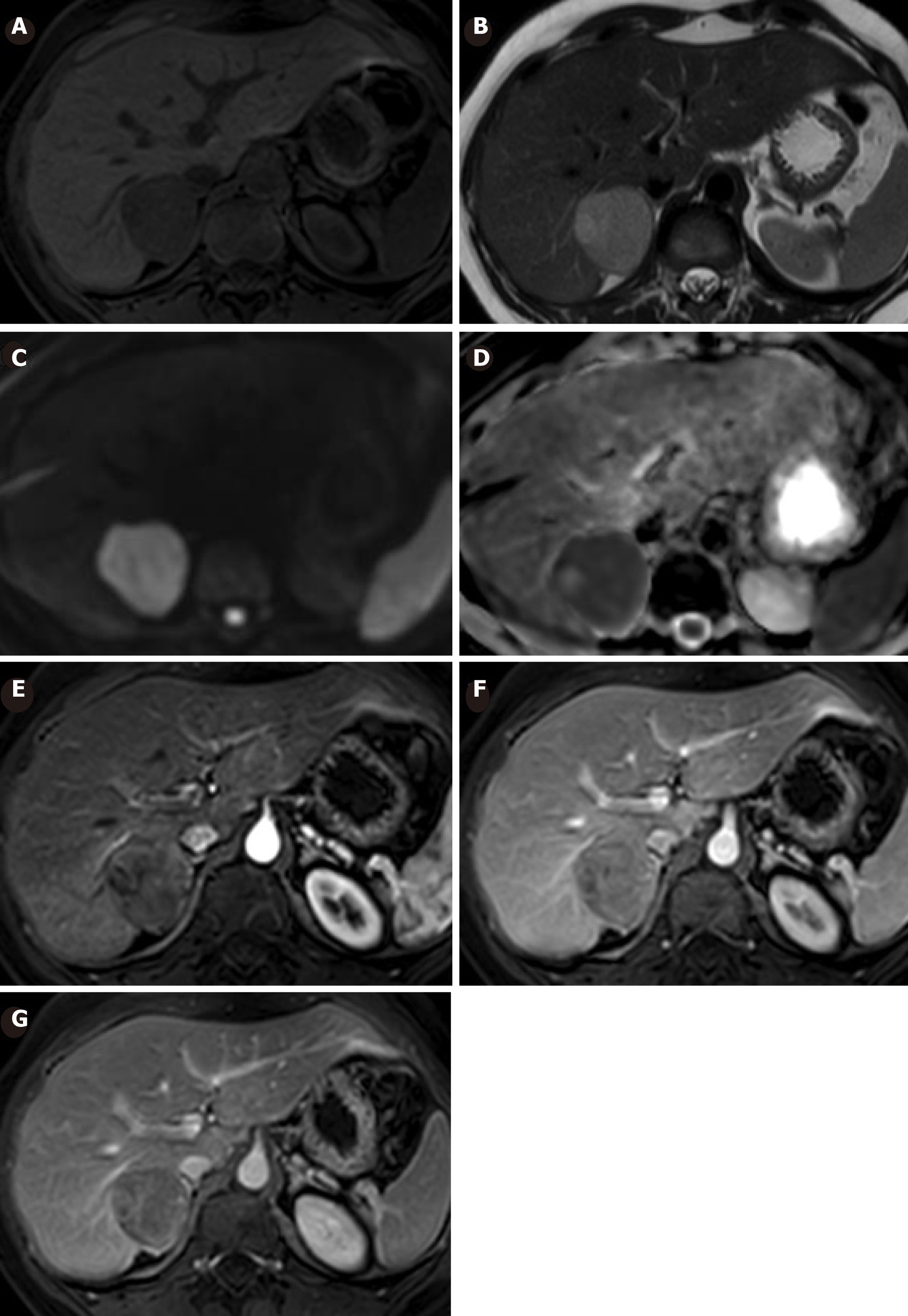

In the last MRI (six months after ovulation induction therapy) the tumor increased in size (40 mm × 39 mm) and a new focal image of 31 mm × 26 mm in contact with its upper region was detected. Both lesions presented heterogeneous enhancement, slighter than the rest of the hepatic parenchyma that persisted in late phases. It showed restriction signs in diffusion-weighted image (DWI), probably because of higher cellularity (Figure 3).

Malignant transformation of HCA.

Surgical treatment was decided. Through a laparotomy approach, the right liver was mobilized. Intraoperative US was performed, revealing two contiguous lesions in segments VI and VII of the liver in contact with the inferior vena cava (IVC). Segmentectomy of the mentioned segments was successfully carried out, with detachment from the IVC and en-block resection with the capsular vein and right adrenal gland that was in intimate contact with the tumor.

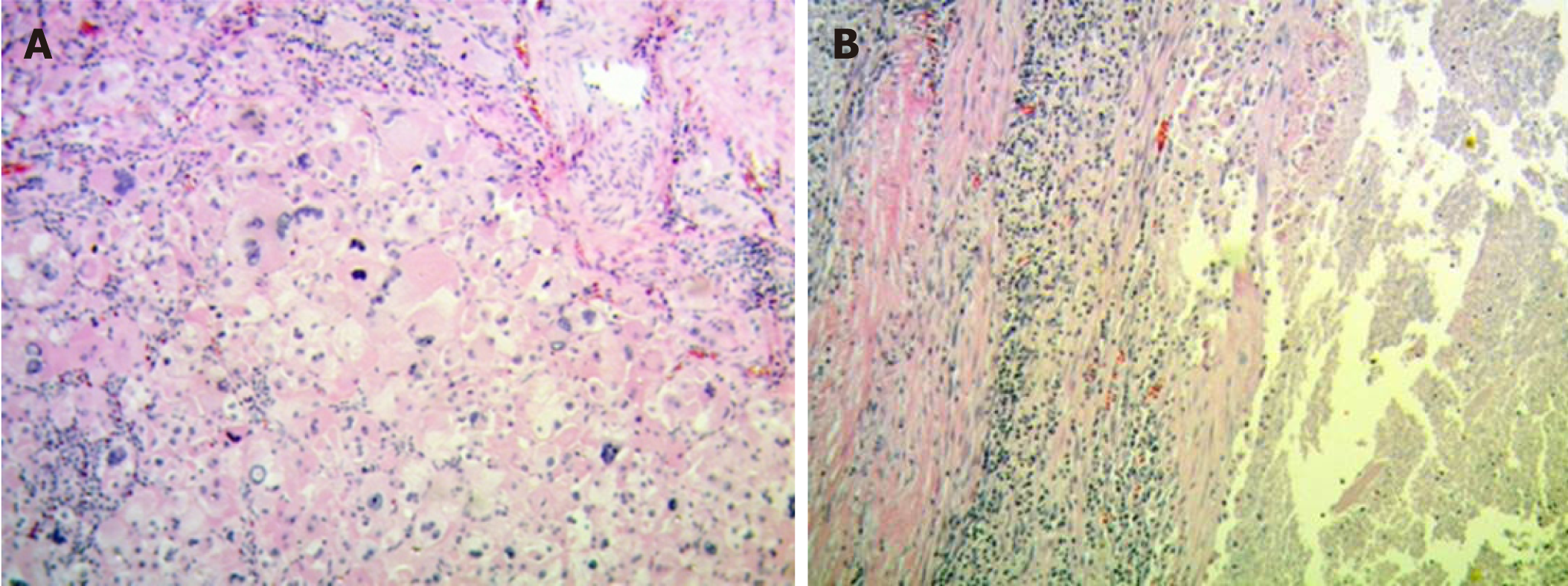

The surgery was carried out successfully. There were neither intraoperative nor postoperative complications, the clinical evolution was favorable and the patient was discharged at day five. The anatomopathological exam revealed a polylobulated tumor of 60 mm × 50 mm × 50 mm constituted by cells with abundant eosinophilic citoplasm, marked anisokaryosis, multinucleation, macronucleoli and frequent atypical mitosis. Extensive areas of intratumoral necrosis were also evident. Growth pattern was expansive and infiltrative and a tumor capsule with infiltration zones was evident. Vascular and lymphatic tumor embolisms coexisted within the lesion (Figure 4).

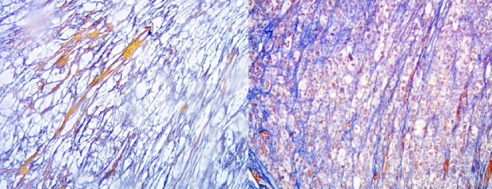

The hepatic parenchyma adjacent to the tumoral formation showed conserved lobular histo-architecture, and absence of steatosis and portal or peri-portal fibro-inflammatory processes. Masson’s Trichromic and Reticulin techniques demonstrated the absence of portal fibrosis and intralobular fibrosis in the hepatic parenchyma adjacent to the tumoral formation (Figure 5).

Regarding immunohistochemistry techniques, Beta-Catenine, Glypican-3, Cytokeratin 7 were negative; HSP-70, CD-68, and Glutamine-Synthetase were focally positive; CD34 revealed abundant vascular frames and non-triad vessels, and Ki-67 expression revealed areas with high prolifferation. The margins of surgical resection and Glisson’s capsule were free of tumor infiltration.

All the described characteristics suggested the malignant transformation of HCA towards trabecular hepatocarcinoma (HCC) with dedifferentiated areas. In three-year of clinical and imaging follow-up, the patient did not evidence tumor recurrence.

HCAs are rare monoclonal benign tumors of the liver with an estimated incidence of 3-4/100000 per year in Europe and North America[2,4]. Most HCAs are solitary and usually incidental findings in patients undergoing radiological work up for unrelated or non-specific symptoms[6]. They closely relate to the dose and duration of OCP use, as well as they tend to regress with the withdrawal of hormonal therapy, so its response to hormonal stimulation is questionless according to several studies[1,7,8]. Once they are diagnosed, discontinuing OCP is indicated in order to prevent potential major complications that can ocurr, like bleeding and/or malignant transformation.

Although its real incidence is not known, Deneve et al[9] reported in a multicenter analysis a 4% malignancy rate in HCA from resected specimens. With the remarkable find that the smallest lesion harboring malignancy was 8 cm. Most of the series that report malignant transformation are focused on HCA treated by resection, which could lead to an overestimation of the risk of malignant transformation[10]. van Aalten et al[11] reported in a systematic review a hemorrhage overall frequency of 27.2%, with an acute rupture and intraperitoneal bleeding in 17.5% of patients. Hemorrhage generally arose in the larger lesions (> 5 cm) but only resected cases were included in this work, so its true incidence is hard to know also.

Currently, a better knowledge about risk factors to develop complications - such as male sex, size greater than 5 cm and β-catenin-activated molecular subtype - has reflected improvements in the selection of patients that would benefit more from a radical treatment vs a conservative treatment[12,13]. In practice, both MRI and biopsy with IHQ are usefull in decision making to help classify HCAs in high or low risk of complications. However, performing a biopsy systematically is still controversial[6]. In the Ronot et al[14] study comparing the efficacy of MRI findings in the diagnosis of these lesions against a routine histological analysis, a 74.5% of agreement between both techniques was observed, with a likelihood ratio of subtype characterization by MRI higher than 20. Therefore, in our center we only perform biopsies when imaging studies are inconclusive. As for this case, we believe a biopsy should have been performed because surgical resection was not considered at the outset. Anyway, in the resected specimen we did not observe β-catenin-activated labeling or any other risk sign, so a categorical HCA biopsy would not have modified our decision of a conservative treatment.

In the past, the relation between an HCA growth ratio and hormonal stimulation in fertile females with these lesions caused them to be discouraged from pregnancy. Today, women with a low-risk HCA who accept the risk of complications related to potential growth during pregnancy could carry it forward without problems[15]. The indispensable condition is that to have a strict surveillance with abdominal US and serum markers. Noels et al[5] monitored twelve women with documented HCA during a total of 17 pregnancies. In 4 cases HCA’s grew during pregnancy, requiring a Caesarean section in 1 patient and radiofrequency ablation in 1 case. All pregnancies reported uneventful course with a successful maternal and fetal outcome. They conclude that if interventions on an HCA are required during pregnancy, they can be performed safely[5].

The patient of this case was a young woman without any children with a strong desire for pregnancy. Considering the patient’s wish and anxiety, the stable characteristics of her HCA, and the lack of evidence about OIFT effect on these lesions, in a multidisciplinary meeting the indication for OIFT has been covenanted.

The patient accepted the risks and the need for strict control. Fortunately and thanks to the rigorous surveillance, malignant transformation of the HCA was early detected and treated with surgery without evidence of recurrence in 3 years of follow-up.

In conclusion, HCAs can be malignant regardless its size and low-risk appearance on MRI when an OIFT is indicated. Therefore, all HCAs should be resected prior to any hormonal therapy given their unpredictable behavior against such stimulation.

We thank Tessa Huber and Patricio Rosas for their disinterested contributions.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Argentina

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Huang XY, Young CJJ S-Editor: Ji FF L-Editor: A E-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Edmondson HA, Henderson B, Benton B. Liver-cell adenomas associated with use of oral contraceptives. N Engl J Med. 1976;294:470-472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 413] [Cited by in RCA: 335] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Vijay A, Elaffandi A, Khalaf H. Hepatocellular adenoma: An update. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:2603-2609. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Sempoux C, Balabaud C, Bioulac-Sage P. Malignant transformation of hepatocellular adenoma. Hepat Oncol. 2014;1:421-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Thomeer MG, Broker M, Verheij J, Doukas M, Terkivatan T, Bijdevaate D, De Man RA, Moelker A, IJzermans JN. Hepatocellular adenoma: when and how to treat? Update of current evidence. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2016;9:898-912. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Noels JE, van Aalten SM, van der Windt DJ, Kok NF, de Man RA, Terkivatan T, Ijzermans JN. Management of hepatocellular adenoma during pregnancy. J Hepatol. 2011;54:553-558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tsilimigras DI, Rahnemai-Azar AA, Ntanasis-Stathopoulos I, Gavriatopoulou M, Moris D, Spartalis E, Cloyd JM, Weber SM, Pawlik TM. Current Approaches in the Management of Hepatic Adenomas. J Gastrointest Surg. 2019;23:199–209. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Barthelmes L, Tait IS. Liver cell adenoma and liver cell adenomatosis. HPB (Oxford). 2005;7:186-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Liau SS, Qureshi MS, Praseedom R, Huguet E. Molecular pathogenesis of hepatic adenomas and its implications for surgical management. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:1869-1882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Deneve JL, Pawlik TM, Cunningham S, Clary B, Reddy S, Scoggins CR, Martin RC, D'Angelica M, Staley CA, Choti MA, Jarnagin WR, Schulick RD, Kooby DA. Liver cell adenoma: a multicenter analysis of risk factors for rupture and malignancy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:640-648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Stoot JH, Coelen RJ, De Jong MC, Dejong CH. Malignant transformation of hepatocellular adenomas into hepatocellular carcinomas: a systematic review including more than 1600 adenoma cases. HPB (Oxford). 2010;12:509-522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 275] [Cited by in RCA: 242] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | van Aalten SM, de Man RA, IJzermans JN, Terkivatan T. Systematic review of haemorrhage and rupture of hepatocellular adenomas. Br J Surg. 2012;99:911-916. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Agrawal S, Agarwal S, Arnason T, Saini S, Belghiti J. Management of Hepatocellular Adenoma: Recent Advances. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1221-1230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Blanc JF, Frulio N, Chiche L, Bioulac-Sage P, Balabaud C. Hepatocellular adenoma management: advances but still a long way to go. Hepat Oncol. 2015;2:171-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ronot M, Bahrami S, Calderaro J, Valla DC, Bedossa P, Belghiti J, Vilgrain V, Paradis V. Hepatocellular adenomas: accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging and liver biopsy in subtype classification. Hepatology. 2011;53:1182-1191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bröker ME, Ijzermans JN, van Aalten SM, de Man RA, Terkivatan T. The management of pregnancy in women with hepatocellular adenoma: a plea for an individualized approach. Int J Hepatol. 2012;2012:725735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |