Published online Mar 16, 2015. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v7.i3.183

Peer-review started: September 3, 2014

First decision: November 19, 2014

Revised: December 12, 2014

Accepted: December 29, 2014

Article in press: December 31, 2014

Published online: March 16, 2015

Processing time: 200 Days and 19.2 Hours

Congenital esophageal stenosis (CES) is an extremely rare malformation, and standard treatment have not been completely established. By years of clinical research, evidence has been accumulated. We conducted systematic review to assess outcomes of the treatment for CES, especially the role of endoscopic modalities. A total of 144 literatures were screened and reviewed. CES was categorized in fibromuscular thickening, tracheobronchial remnants (TBR) and membranous web, and the frequency was 54%, 30% and 16%, respectively. Therapeutic option includes surgery and dilatation, and surgery tends to be reserved for ineffective dilatation. An essential point is that dilatation for TBR type of CES has low success rate and high rate of perforation. TBR can be distinguished by using endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS). Overall success rate of dilatation for CES with or without case selection by using EUS was 90% and 29%, respectively. Overall rate of perforation with or without case selection was 7% and 24%, respectively. By case selection using EUS, high success rate with low rate of perforation could be achieved. In conclusion, endoscopic dilatation has been established as a primary therapy for CES except TBR type. Repetitive dilatation with gradual step-up might be one of safe ways to minimize the risk of perforation.

Core tip: Congenital esophageal stenosis (CES) is a rare malformation consisting of 3 types; fibromuscular thickening, tracheobronchial remnants (TBR) and membranous web. Endoscopic dilatation has been established as a primary therapy for CES except TBR type. Endoscopic ultrasonography is useful to distinguish TBR from other types of CES. Repetitive dilatation with gradual step-up is recommended to minimize the risk of perforation.

- Citation: Terui K, Saito T, Mitsunaga T, Nakata M, Yoshida H. Endoscopic management for congenital esophageal stenosis: A systematic review. World J Gastrointest Endosc 2015; 7(3): 183-191

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5190/full/v7/i3/183.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v7.i3.183

Congenital esophageal stenosis (CES) is an extremely rare malformation, and diagnostic criteria and standard treatment have not been completely established. By years of clinical research, evidence for the management of CES has been accumulated. In the management of CES, surgery and endoscopic modalities play a key role. Endoscopic management could be an effective and less-invasive, however, the risk of therapies and therapeutic margin should be considered. The aims of this systematic review were to identify all published studies of endoscopic management of CES and to assess outcomes in terms of relief of the stricture and complication rates. Frequency and characters of 3 categories of CES, and relationship with associated anomalies were also reviewed.

A Definition of CES was based on the description by Nihoul-Fékété[1]; “an intrinsic stenosis of the esophagus, present although not necessarily symptomatic at birth, which is caused by congenital malformation of esophageal wall architecture”.

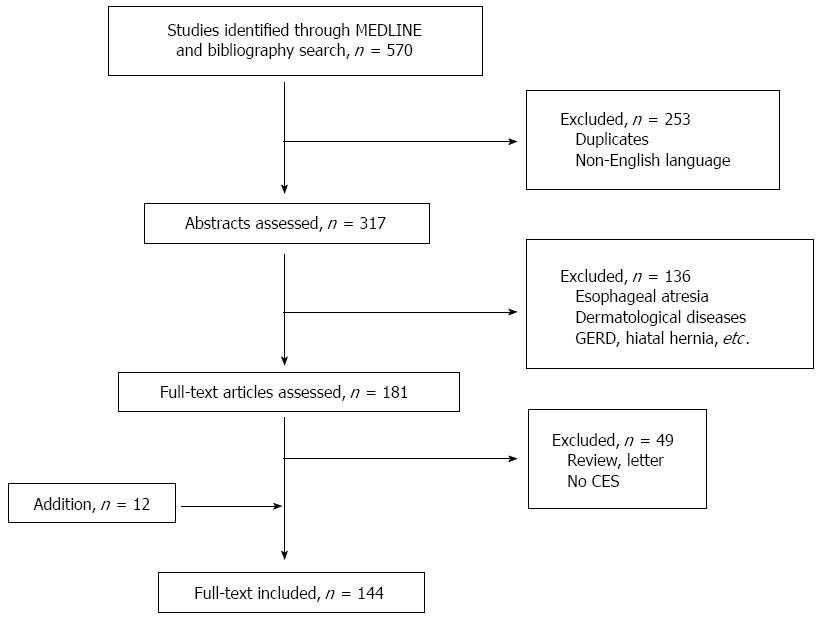

Systematic review of English-language articles reporting CES was conducted by searching the PubMed database, in July 2014. Search terms “congenital” AND “esophageal stenosis” AND “endosc*”, and MeSH term“Esophageal Stenosis” AND the term “congenital” were used. The references of each of the included studies were then screened for any additionally relevant articles. Studies were selected according to the following inclusion/exclusion criteria: the only inclusion criteria was diagnosis of CES, defined as intrinsic stenosis of the esophagus. Esophageal stricture due to compression by cardiac/vascular malformations or intrathoracic tumor was excluded, if it is “congenital”. Secondary esophageal stenosis due to gastro-esophageal reflux, postoperative anastomotic stricture of esophageal atresia (EA) with/without tracheal fistula, leiomyoma and dermatological diseases including epidermolysis bullosa, dyskeratosis congenita, Rothmund Thomson syndrome and Goltz syndrome were also excluded. Review articles and mere letters were excluded. There were no exclusions based on patient numbers or length of follow-up. Accordingly, a total of 570 studies were identified by the initial searches, of which 144 studies satisfied the selection criteria (Figure 1). All the studies included were case reports or retrospective observational studies.

Investigators have commented on the rarity of CES, but the true incidence is still unknown. Bluestone et al[2] treated 24 cases of CES and approximately 200 cases of trachea-esophageal fistula in the single institution during the same 15 years, and estimated that the incidence of CES was one per 25000 births using that the incidence of tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF) was one per 2500 births[2]. Nihoul-Fékété et al[1] found 20 cases of CES and 484 cases of EA in the single institution during the same 25 years (1960-1984). According to this data, incidence of CES was lower than 1/20 of that of EA. Therefore, 1/25000-50000 live births is thought to be the incident rate of CES. These data are reliable and basically correct, but the frequency data should be revised based on the data at least in the 2000s.

The classification of CES has been confusing mainly because of its infrequency. Histological classification has been difficult because surgical specimens cannot be obtained if the only bougie can improves the symptom. Furthermore, it has also been difficult to differentiate CES from other non-congenital esophageal stricture such as achalasia, peptic esophageal stenosis due to gastroesophageal reflux and herpetic esophageal stenosis[3,4].

Various classification of CES had been proposed to date. Ohkawa et al[5] (1975) reported 5 entities of CES including tracheobronchial remnants, fibromuscular thickening, esophageal epithelioma, short esophagus and achalasia. Sneed et al[6] (1979) considered that there are congenital fibromuscular thickening (FMT), tracheobronchial remnants (TBR) and membranous web (MW) in the category of CES. Nihoul-Fékété (1989) clearly define CES and categorized the cases based on these 3 entities[1]. This categorization based on this sophisticated study has been broadly accepted to date. Ramesh et al[7] (2001) categorized CES into 3 groups; isolated segmental type, isolated diaphragm type and combined type. Isolated segmental type corresponds FMT and TBR, isolated diaphragm type corresponds MW and combined type corresponds segmental stenosis distal EA/TEF or MW. Although this classification involves the etiological consideration of CES, it is too complicated to use in clinical practice.

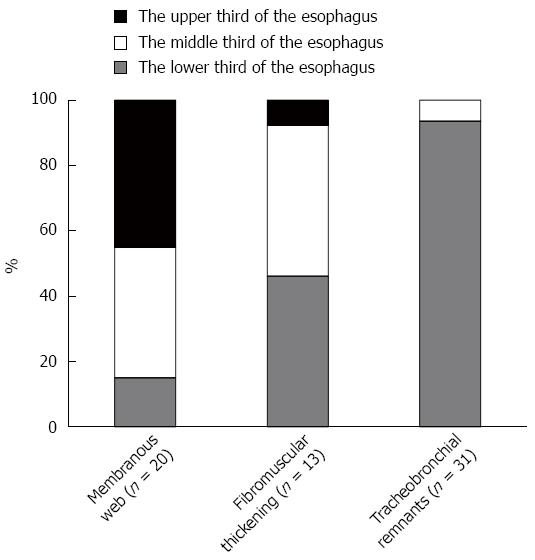

Frequency of 3 categories of CES were assessed by using the 3 observational studies including pediatric CES cases with detailed categorization (Table 1)[1,8,9]. Accordingly, overall frequency of FMT, TBR and MW were 53.8%, 29.9% and 16.2%, respectively. Locations of stenosis in each categories were assessed by using 52 case reports including 64 patients (Figure 2). Trends were as follows; MW mainly in the upper or middle third of the esophagus[10-27], FMT mainly in the middle or lower third[28-39], and TBR mostly in the lower third[6,40-60].

Additionally, multiple web type of CES has been reported mainly in adults[61]. Only 1 pediatric case with multiple web has been reported[62].

CES associated with esophageal atresia (EA) and/or tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF) is not so rare, and 44 cases have been reported as case(s) report to date[12,22,26,28,31,33,37,44,47,50,55,63-75]. To assess relationship and EA and/or TEF, 14 observational studies of pediatric cases were reviewed[1,2,8,9,76-85]. According to the 4 observational studies[76,80,81,84], overall incidence rate of CES among patients with EA and/or TEF was 9.6% (Table 2). All the CES located in the middle to lower third of the esophagus; 13.5% in middle third of the esophagus, and 86.5% in lower third of the esophagus. Pathological findings of CES associated with TEF were not clear, because not all the cases had surgical specimens. In 15 cases (27% of CES cases), pathological assessment was performed; 10 cases (67%) had tracheobronchial remnant and 5 cases (33%) had fibromuscular stenosis. CES in TEF/EA is not a rare association, therefore, careful attention is required during the management of TEF/EA, especially in postoperative esophagogram.

According to the 10 observational studies[1,2,8,9,77-79,82,83,85], overall incidence rate of EA and/or TEF among patients with CES was 24.8% (Table 3). Variation of the incident rate in each study may depend on study period, the role of institution and study design. Type of EA were not so different from original proportion; EA in 2.4%, EA+TEF in 92.7% and TEF in 4.9% of the cases. CES cases with complicated form of EA/TEF which cannot be classified were also reported[6,64].

| Ref. | Cases | Incidence rate | EA | EA + TEF | TEF |

| Bluestone et al[2] (1969) | 0/24 | 0.0% | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nishina et al[77] (1981) | 4/81 | 4.9% | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| Dominguez et al[78] (1985) | 5/34 | 14.7% | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| Nihoul-Fékété et al[1] (1987) | 2/20 | 10.0% | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Yeung et al[79] (1992) | 6/8 | 75.0% | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| Vasudevan et al[82] (2002) | 4/6 | 66.7% | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Takamizawa et al[8] (2002) | 13/36 | 36.1% | 0 | 13 | 0 |

| Amae et al[83] (2003) | 4/14 | 28.6% | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Romeo et al[85] (2011) | 15/47 | 31.9% | 0 | 15 | 0 |

| Michaud et al[9] (2013) | 29/61 | 47.5% | 0 | 29 | 0 |

| Total | 82/331 | 24.8% | 2 (2.4%) | 76 (92.7%) | 4 (4.9%) |

Additionally, another esophageal malformation with CES, including esophageal duplication[22,50,86], diverticulum[18] and achalasia[11] were also reported.

Seven observational studies with detailed description about associated anomalies were reviewed[1,8,77-79,82,83]. These studies included a total of 199 cases of CES. The cases without any anomalies accounted for 55.3% of CES cases. Associated anomalies other than esophageal malformation were miscellaneous. Relatively frequent anomalies were as follows; congenital heart disease (4.5%), 21trisomy (4.0%), anorectal anomaly (2.0%), duodenal atresia (1.5%), tracheal malacia (1.5%), esophageal hiatal hernia (1.0%).

It is difficult to prove whether the adult cases with esophageal stenosis are truly “congenital”. Actually, webs of the cervical esophagus have been commonly associated with Plummer-Vinson syndrome. In the largest series of adult CES cases, 62% of cases with upper esophageal webs had anemia, and all of them were female[87]. Khosla et al[88] also reported that among 117 patients with iron deficiency anemia, 6 cases (5.1%) had upper esophageal webs. Meanwhile, esophageal stenosis may also be found without the Plummer-Vinson syndrome. We found 24 case reports including 30 adult cases of CES with the categorization[10,11,13,15-18,20,21,40,41,59,89-99]. In these, 26 cases (86.7%) had MW type of CES[10,11,13,15-18,20,21,89-97,98,99]. In these, 16 cases had multiple webs[89-99], which was similar to ring of the trachea. Younes et al[61] treated 10 adult cases of multiple esophageal webs during 7 years, and stated that CES in adults is under-recognized cause for intermittent, long-standing dysphagia. Although extremely rare, TBR[40,41,59] and FMT[34] type of CES were also reported in adults.

Occurrence of CES within a family was reported only in the 2 literatures; in father and son[94], and sisters[96]. They all were over middle age, suffered from dysphagia and/or food impaction for long duration, and had multiple esophageal webs (one of the sisters had no detail). In the former family, the son had male sibling who died 1 wk after birth because of an inability to swallow. In earlier reports, the nature of multiple esophageal webs has been speculated to be either congenital or acquired[89], and still remains unclear.

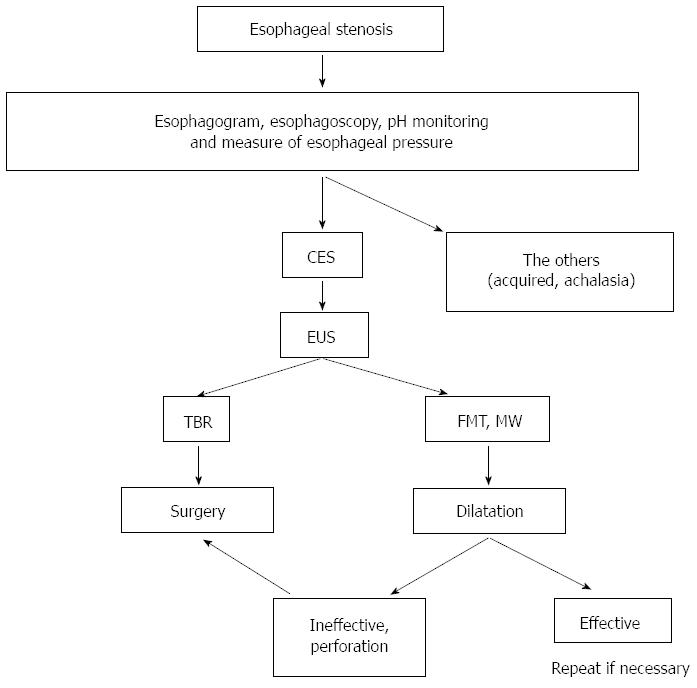

In diagnosis of CES, it is essential to exclude postnatally acquired stenoses (peptic, caustic, infectious, neoplastic), extrinsic compression, and achalasia[1]. Careful medical interview is of key importance. Both esophagogram and esophagoscopy is required to know location, range, form and degree of stenosis. To exclude peptic stenosis, pH monitoring may be useful. To exclude achalasia, measure of esophageal pressure is also informative.

Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) is brilliant way to classify the CES, especially distinguishing TBR from FMT[8,54,100,101]. By using this modality, the cartilage in the esophageal wall is visualized as low echoic area[54,100] or high echoic area[8,101]. Whether CES is classified as TBR or not is important information to determine the therapeutic strategy, because CES of TBR should be managed by surgery, not bougie due to high rate of perforation[55].

Therapeutic option consists of dilatation and surgery. Although surgery tends to be reserved for ineffective dilatation, efficacy and risk of dilatation has been controversial. We, therefore, reviewed the literatures in which more than 5 cases of CES were treated by dilatation[1,8,9,79,81-83,85]. Studies were divided into two groups by whether EUS was used for case selection or not. EUS was to distinguish TBR type of CES. Accordingly, overall success rate of dilatation for CES with or without case selection was 89.7% and 28.9%, respectively (Table 4). Overall rate of perforation with or without case selection was 7.4% and 23.9%, respectively (Table 5). By using EUS, high success rate with low rate of perforation could be achieved. On the basis of this knowledge, flow chart of treatment is shown in Figure 3.

| Ref. | Case selection by EUS | Modality | |

| + | - | ||

| Success rate | |||

| Takamizawa et al[8] (2002) | 16/21 (76.2%) | - | BD |

| Romeo et al[85] (2011) | 45/47 (95.7%) | - | BD |

| Nihoul-Fékété et al[1] (1987) | - | 7/14 (50.0%) | BD or TD |

| Yeung et al[79] (1992) | - | 0/7 (0.0%) | BD or TD |

| Kawahara et al[81] (2001) | - | 2/9 (22.2%) | BD |

| Vasudevan et al[82] (2002) | - | 3/7 (42.9%) | TD |

| Amae et al[83] (2003) | - | 3/11 (27.3%) | BD or TD |

| Michaud et al[9] (2013) | - | 13/49 (26.5%) | BD or TD |

| Total | 611/68 (89.7%) | 28/97 (28.9%) | |

| Ref. | Case selection by EUS | Modality | |

| + | - | ||

| Rate of perforation | |||

| Takamizawa et al[8] (2002) | 0/21 (0.0%) | - | BD |

| Romeo et al[85] (2011) | 15/47 (10.6%) | - | BD |

| Nihoul-Fékété et al[1] (1987) | - | 6/14 (42.9%) | BD or TD |

| Yeung et al[79] (1992) | - | 1/7 (14.3%) | BD or TD |

| Newman et al[80] (1997) | 3/18 (16.7%) | BD | |

| Kawahara et al[81] (2001) | - | 4/9 (44.4%) | BD |

| Amae et al[83] (2003) | - | 1/11 (9.1%) | BD or TD |

| Fan et al[104] (2011) | - | 1/8 (12.5%) | BD |

| Total | 5/68 (7.4%) | 16/67 (23.9%) | |

As a technique of dilatation, there are tapered dilator and balloon dilatator, but there has been no comparison study of these. Some prefer balloon dilator because it enable expanding force to focus on the stenotic segment without shear stress, resulting in more effective and safer[8,102]. Appropriate diameter of dilatation for CES is still unknown. Kozarek et al[103] suggested that inflation of a single large-diameter dilator of less than 15 mm or an incremental dilation of more than 3 mm may be safe in simple esophageal strictures in adults. Fan et al[104] reported 9 procedures of balloon dilatation for CES including 1 esophageal perforation. Although there was no statistical significance, mean balloon diameter of the procedure with/without perforation was 12.1 mm and 15.0 mm, respectively. Mean dilation achieved with/without perforation was 5.4 mm and 8.4 mm, respectively. Not surprisingly, large dilatation with large increment might be a risk of perforation. Therefore, repetitive dilatation with gradual step-up might be one of safe ways to minimize the risk of perforation.

In cases of MW type of CES, efficacy of endoscopic dilatation with radial incision of the web has been reported. Instruments for incision include electrocoagulation[17,19,105], high-frequency-wave[27] and laser[23]. Nose et al[27] used balloon catheter for pulling up the web from the distal side during incision. Adverse events during dilatation with incision have not been reported.

It is well known that the association of Plummer-Vinson syndrome with carcinoma of the mouth, hypopharynx and upper esophagus. In the 58 adult cases of MW type of CES, 9 cases (15.5%) had carcinoma; buccal carcinoma in 6, esophageal carcinoma in 3[88]. Other than MW type, only one case has been reported, who had esophageal carcinoma associated with FMT type of CES; 65-year-old man who had suffered from dysphagia and vomiting since birth, but had not received any treatment because of mild symptom, underwent esophagectomy for worsening symptom. The resected specimen revealed squamous cell carcinoma in the region of fibromuscular stenosis[34]. The authors speculated that chronic mechanical stimulation by food trapped above the stenosis may have induced dysplasia of the mucosa. Special attention should be paid to status of the esophageal passage. Long-term functional prognosis after dilatation of pediatric CES has not been reported. Further studies are still needed.

Endoscopic dilatation has been established as a primary therapy for CES except TBR type. EUS is useful to distinguish TBR from other types of CES. Repetitive dilatation with gradual step-up is recommended to minimize the risk of perforation.

P- Reviewer: Shimi SM, Xiao Q S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Nihoul-Fékété C, De Backer A, Lortat-Jacob S, Pellerin D. Congenital esophageal stenosis. A review of 20 cases. Pediatr Surg Int. 1987;2:86-92. |

| 2. | Bluestone CD, Kerry R, Sieber WK. Congenital esophageal stenosis. Laryngoscope. 1969;79:1095-1103. |

| 3. | Valerio D, Jones PF, Stewart AM. Congenital oesophageal stenosis. Arch Dis Child. 1977;52:414-416. |

| 4. | Rossier A, de Montis G, Chabrolle JP. Congenital oesophageal stenosis and herpes simplex infection. Arch Dis Child. 1977;52:982. |

| 5. | Ohkawa H, Takahashi H, Hoshino Y, Sato H. Lower esophageal stenosis in association with tracheobronchial remnants. J Pediatr Surg. 1975;10:453-457. |

| 6. | Sneed WF, LaGarde DC, Kogutt MS, Arensman RM. Esophageal stenosis due to cartilaginous tracheobronchial remnants. J Pediatr Surg. 1979;14:786-788. |

| 7. | Ramesh JC, Ramanujam TM, Jayaram G. Congenital esophageal stenosis: report of three cases, literature review, and a proposed classification. Pediatr Surg Int. 2001;17:188-192. |

| 8. | Takamizawa S, Tsugawa C, Mouri N, Satoh S, Kanegawa K, Nishijima E, Muraji T. Congenital esophageal stenosis: Therapeutic strategy based on etiology. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:197-201. |

| 9. | Michaud L, Coutenier F, Podevin G, Bonnard A, Becmeur F, Khen-Dunlop N, Auber F, Maurel A, Gelas T, Dassonville M. Characteristics and management of congenital esophageal stenosis: findings from a multicenter study. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:186. |

| 10. | Adler RH. Congenital esophageal webs. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1963;45:175-185. |

| 11. | Salzman AJ. Lower esophageal WEB asssociated with achalasia of the esophagus. N Y State J Med. 1965;65:1922-1925. |

| 12. | Azimi F, O’Hara AE. Congenital intraluminal mucosal web of the esophagus with tracheo-esophageal fistula. Am J Dis Child. 1973;125:92-95. |

| 13. | Liebman WM, Samloff IM. Congenital membranous stenosis of the midesophagus. A case report and literature survey. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1973;12:660-662. |

| 14. | Gilat T, Rozen P. Fiberoptic endoscopic diagnosis and treatment of a congenital esophageal diaphragm. Am J Dig Dis. 1975;20:781-785. |

| 15. | Ikard RW, Rosen HE. Midesophageal web in adults. Ann Thorac Surg. 1977;24:355-358. |

| 16. | Shauffer IA, Phillips HE, Sequeira J. The jet phenomenon: a manifestation of esophageal web. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1977;129:747-748. |

| 17. | Acosta JC. Congenital stenosis of the esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1981;27:197-198. |

| 18. | Mercer CD, Hill LD. Esophageal web associated with Zenker’s diverticulum: a possible cause of continuing dysphagia after diverticulectomy. Can J Surg. 1985;28:375-376. |

| 19. | Mares AJ, Bar-Ziv J, Lieberman A, Tovi F. Congenital esophageal stenosis. Transendoscopic web incision. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1986;8:555-558. |

| 20. | Shergill IS, Khanna S, Kaur J. Congenital upper esophageal web. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 1986;28:156-159. |

| 21. | Beggs D, Morgan WE. Spontaneous perforation of cervical oesophagus associated with oesophageal web. J Laryngol Otol. 1989;103:537-538. |

| 22. | Snyder CL, Bickler SW, Gittes GK, Ramachandran V, Ashcraft KW. Esophageal duplication cyst with esophageal web and tracheoesophageal fistula. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31:968-969. |

| 23. | Roy GT, Cohen RC, Williams SJ. Endoscopic laser division of an esophageal web in a child. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31:439-440. |

| 24. | Grabowski ST, Andrews DA. Upper esophageal stenosis: two case reports. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31:1438-1439. |

| 25. | Kumuro H, Makino S, Tsuchiya I, Shibusawa H, Kusaka T, Nishi A. Cervical esophageal web in a 13-year-old boy with growth failure. Pediatr Int. 1999;41:568-570. |

| 26. | Nagae I, Tsuchida A, Tanabe Y, Takahashi S, Minato S, Aoki T. High-grade congenital esophageal stenosis owing to a membranous diaphragm with tracheoesophageal fistula. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:e11-e13. |

| 27. | Nose S, Kubota A, Kawahara H, Okuyama H, Oue T, Tazuke Y, Ihara Y, Okada A. Endoscopic membranectomy with a high-frequency-wave snare/cutter for membranous stenosis in the upper gastrointestinal tract. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40:1486-1488. |

| 28. | Tuqan NA. Annular stricture of the esophagus distal to congenital tracheoesophageal fistula. Surgery. 1962;52:394-395. |

| 29. | Takayanagi K, Ii K, Komi N. Congenital esophageal stenosis with lack of the submucosa. J Pediatr Surg. 1975;10:425-426. |

| 30. | Groote AD, Laurini RN, Polman HA. A case of congenital esophageal stenosis. Hum Pathol. 1985;16:1170-1171. |

| 31. | Homnick DN. H-type tracheoesophageal fistula and congenital esophageal stenosis. Chest. 1993;103:308-309. |

| 32. | Garau P, Orenstein SR. Congenital esophageal stenosis treated by balloon dilation. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1993;16:98-101. |

| 33. | Pesce C, Musi L, Campobasso P, Costa L, Mercurella A. Conservative non-surgical management of congenital oesophageal stenosis associated with oesophageal atresia. Ital J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;31:899-900. |

| 34. | Tabira Y, Yasunaga M, Sakaguchi T, Okuma T, Yamaguchi Y, Kuhara H, Honda Y, Iyama K, Kawasuji M. Adult case of squamous cell carcinoma arising on congenital esophageal stenosis due to fibromuscular hypertrophy. Dis Esophagus. 2002;15:336-339. |

| 35. | Setty SP, Harrison MW. Congenital esophageal stenosis: a case report and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2004;14:283-286. |

| 36. | Machmouchi MA, Al Harbi M, Bakhsh KA, Al Shareef ZH. Congenital esophageal stenosis. Saudi Med J. 2004;25:648-650. |

| 37. | Queizán A, Martínez L. Congenital segmental fibromuscular hypertrophy of the esophagus and esophageal atresia: an uncommon case. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2006;16:201-204. |

| 38. | Martinez-Ferro M, Rubio M, Piaggio L, Laje P. Thoracoscopic approach for congenital esophageal stenosis. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:E5-E7. |

| 39. | Al-Tokhais TI, Ahmed AM, Aljubab AS. Congenital esophageal stenosis and antral web. A new association and management challenge. Saudi Med J. 2010;31:1166-1168. |

| 40. | Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital; case 42411. N Engl J Med. 1956;255:707-710. |

| 41. | Bergmann M, charnas RM. Tracheobronchial rests in the esophagus; their relation to some benign strictures and certain types of cancer of the esophagus. J Thorac Surg. 1958;35:97-104. |

| 42. | Paulino F, Roselli A, Aprigliano F. Congenital esophageal stricture due to tracheobraonchial remnants. Surgery. 1963;53:547-550. |

| 43. | Ishida M, Tsuchida Y, Saito S, Tsunoda A. Congenital esophageal stenosis due to tracheobronchial remnants. J Pediatr Surg. 1969;4:339-345. |

| 44. | Spitz L. Congenital esophageal stenosis distal to associated esophageal atresia. J Pediatr Surg. 1973;8:973-974. |

| 45. | Marcus PB, de Wet Lubbe JJ, Muller Botha GS. An unusual cause of congenital oesophageal stenosis. S Afr J Surg. 1973;11:145-146. |

| 46. | Anderson LS, Shackelford GD, Mancilla-Jimenez R, McAlister WH. Cartilaginous esophageal ring: a cause of esophageal stenosis in infants and children. Radiology. 1973;108:665-666. |

| 47. | Deiraniya AK. Congenital oesophageal stenosis due to tracheobronchial remnants. Thorax. 1974;29:720-725. |

| 48. | Rose JS, Kassner EG, Jurgens KH, Farman J. Congenital oesophageal strictures due to cartilaginous rings. Br J Radiol. 1975;48:16-18. |

| 49. | Briceño LI, Grases PJ, Gallego S. Tracheobronchial and pancreatic remnants causing esophageal stenosis. J Pediatr Surg. 1981;16:731-732. |

| 50. | Ibrahim NB, Sandry RJ. Congenital oesophageal stenosis caused by tracheobronchial structures in the oesophageal wall. Thorax. 1981;36:465-468. |

| 51. | Bar-Maor JA, Posen JA, Hamilton DG, Chappell JS. Congenital oesophageal stenosis due to cartilaginous tracheobronchial remnants. S Afr J Surg. 1983;21:43-47. |

| 52. | Shoshany G, Bar-Maor JA. Congenital stenosis of the esophagus due to tracheobronchial remnants: a missed diagnosis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1986;5:977-979. |

| 53. | Olguner M, Ozdemir T, Akgür FM, Aktuğ T. Congenital esophageal stenosis owing to tracheobronchial remnants: a case report. J Pediatr Surg. 1997;32:1485-1487. |

| 54. | Kouchi K, Yoshida H, Matsunaga T, Ohtsuka Y, Nagatake E, Satoh Y, Terui K, Mitsunaga T, Ochiai T, Arima M. Endosonographic evaluation in two children with esophageal stenosis. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:934-936. |

| 55. | Zhao LL, Hsieh WS, Hsu WM. Congenital esophageal stenosis owing to ectopic tracheobronchial remnants. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:1183-1187. |

| 56. | Maeda K, Hisamatsu C, Hasegawa T, Tanaka H, Okita Y. Circular myectomy for the treatment of congenital esophageal stenosis owing to tracheobronchial remnant. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:1765-1768. |

| 57. | Saito T, Ise K, Kawahara Y, Yamashita M, Shimizu H, Suzuki H, Gotoh M. Congenital esophageal stenosis because of tracheobronchial remnant and treated by circular myectomy: a case report. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:583-585. |

| 58. | Deshpande AV, Shun A. Laparoscopic treatment of esophageal stenosis due to tracheobronchial remnant in a child. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2009;19:107-109. |

| 59. | Longcroft-Wheaton G, Ellis R, Somers S. Dysphagia in a 30-year-old woman: too old for a congenital abnormality? Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2010;71:170-171. |

| 60. | Quiros JA, Hirose S, Patino M, Lee H. Esophageal tracheobronchial remnant, endoscopic ultrasound diagnosis, and surgical management. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;56:e14. |

| 61. | Younes Z, Johnson DA. Congenital esophageal stenosis: clinical and endoscopic features in adults. Dig Dis. 1999;17:172-177. |

| 62. | Carlisle WR. A case of multiple esophageal webs and rings. Gastrointest Endosc. 1984;30:184-185. |

| 63. | Goldenberg IS. An unusual variation of congenital tracheo-esophageal fistula. J Thorac cardiovasc Surg. 1960;40:114-116. |

| 64. | Lister J. An unusual variation of oesophageal atresia. Arch Dis Child. 1963;38:176-179. |

| 65. | Stephens HB. H-type tracheoesophageal fistula complicated by esophageal stenosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1970;59:325-329. |

| 66. | Mahour GH, Johnston PW, Gwinn JL, Hays DM. Congenital esophageal stenosis distal to esophageal atresia. Surgery. 1971;69:936-939. |

| 68. | Mortensson W. Congenital oesophageal stenosis distal to oesophageal atresia. Pediatr Radiol. 1975;3:149-151. |

| 69. | Sheridan J, Hyde I. Oesophageal stenosis distal to oesophageal atresia. Clin Radiol. 1990;42:274-276. |

| 70. | Neilson IR, Croitoru DP, Guttman FM, Youssef S, Laberge JM. Distal congenital esophageal stenosis associated with esophageal atresia. J Pediatr Surg. 1991;26:478-481; discussion 481-482. |

| 71. | Shorter NA, Mooney DP, Vaccaro TJ, Sargent SK. Hydrostatic balloon dilation of congenital esophageal stenoses associated with esophageal atresia. J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35:1742-1745. |

| 72. | Babu R, Hutton KA, Spitz L. H-type tracheo-oesophageal fistula with congenital oesophageal stenosis. Pediatr Surg Int. 2005;21:386-387. |

| 73. | Jones DW, Kunisaki SM, Teitelbaum DH, Spigland NA, Coran AG. Congenital esophageal stenosis: the differential diagnosis and management. Pediatr Surg Int. 2010;26:547-551. |

| 74. | van Poll D, van der Zee DC. Thoracoscopic treatment of congenital esophageal stenosis in combination with H-type tracheoesophageal fistula. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47:1611-1613. |

| 75. | Escobar MA, Pickens MK, Holland RM, Caty MG. Oesophageal atresia associated with congenital oesophageal stenosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013. |

| 76. | Holinger PH, Johnston KC. Postsurgical endoscopid problems of congenital esophageal atresia. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1963;72:1035-1049. |

| 77. | Nishina T, Tsuchida Y, Saito S. Congenital esophageal stenosis due to tracheobronchial remnants and its associated anomalies. J Pediatr Surg. 1981;16:190-193. |

| 78. | Dominguez R, Zarabi M, Oh KS, Bender TM, Girdany BR. Congenital oesophageal stenosis. Clin Radiol. 1985;36:263-266. |

| 79. | Yeung CK, Spitz L, Brereton RJ, Kiely EM, Leake J. Congenital esophageal stenosis due to tracheobronchial remnants: a rare but important association with esophageal atresia. J Pediatr Surg. 1992;27:852-855. |

| 80. | Newman B, Bender TM. Esophageal atresia/tracheoesophageal fistula and associated congenital esophageal stenosis. Pediatr Radiol. 1997;27:530-534. |

| 81. | Kawahara H, Imura K, Yagi M, Kubota A. Clinical characteristics of congenital esophageal stenosis distal to associated esophageal atresia. Surgery. 2001;129:29-38. |

| 82. | Vasudevan SA, Kerendi F, Lee H, Ricketts RR. Management of congenital esophageal stenosis. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:1024-1026. |

| 83. | Amae S, Nio M, Kamiyama T, Ishii T, Yoshida S, Hayashi Y, Ohi R. Clinical characteristics and management of congenital esophageal stenosis: a report on 14 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:565-570. |

| 84. | Yoo HJ, Kim WS, Cheon JE, Yoo SY, Park KW, Jung SE, Shin SM, Kim IO, Yeon KM. Congenital esophageal stenosis associated with esophageal atresia/tracheoesophageal fistula: clinical and radiologic features. Pediatr Radiol. 2010;40:1353-1359. |

| 85. | Romeo E, Foschia F, de Angelis P, Caldaro T, Federici di Abriola G, Gambitta R, Buoni S, Torroni F, Pardi V, Dall’oglio L. Endoscopic management of congenital esophageal stenosis. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46:838-841. |

| 86. | Fuchs J, Grasshoff S, Schirg E, Glüer S, Bürger D. Tubular esophageal duplication associated with esophageal stenosis, pericardial aplasia, diaphragmatic hernia, ramification anomaly of lower lobe bronchus and partial pancreas anulare. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1998;8:102-104. |

| 87. | Shamma’a MH, Benedict EB. Esophageal webs; a report of 58 cases & an attempt at classification. N Engl J Med. 1958;259:378-384. |

| 88. | Khosla SN. Cricoid webs--incidence and follow-up study in Indian patients. Postgrad Med J. 1984;60:346-348. |

| 89. | Shiflett DW, Gilliam JH, Wu WC, Austin WE, Ott DJ. Multiple esophageal webs. Gastroenterology. 1979;77:556-559. |

| 90. | Longstreth GF, Wolochow DA, Tu RT. Double congenital midesophageal webs in adults. Dig Dis Sci. 1979;24:162-165. |

| 91. | Janisch HD, Eckardt VF. Histological abnormalities in patients with multiple esophageal webs. Dig Dis Sci. 1982;27:503-506. |

| 92. | Munitz HA, Ott DJ, Rocamora LR, Wu WC. Multiple webs of the esophagus. South Med J. 1983;76:405-406. |

| 93. | Agarwal VP, Marcel BR. Multiple esophageal rings. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:147-149. |

| 94. | Harrison CA, Katon RM. Familial multiple congenital esophageal rings: report of an affected father and son. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:1813-1815. |

| 95. | Pokieser P, Schima W, Schober E, Böhm P, Stacher G, Levine MS. Congenital esophageal stenosis in a 21-year-old man: clinical and radiographic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170:147-148. |

| 98. | Gonzalez JA, Craft CM, Knight TT, Messerschmidt WH. Superimposed spontaneous esophageal perforation in congenital esophageal stenosis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;77:1098-1100. |

| 99. | Smith MA, Patterson GA, Cooper JD. Dysphagia in the young male: the ringed esophagus. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81:354-356. |

| 100. | Bocus P, Realdon S, Eloubeidi MA, Diamantis G, Betalli P, Gamba P, Zanon GF, Battaglia G. High-frequency miniprobes and 3-dimensional EUS for preoperative evaluation of the etiology of congenital esophageal stenosis in children (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:204-207. |

| 101. | Usui N, Kamata S, Kawahara H, Sawai T, Nakajima K, Soh H, Okada A. Usefulness of endoscopic ultrasonography in the diagnosis of congenital esophageal stenosis. J Pediatr Surg. 2002;37:1744-1746. |

| 102. | Sato Y, Frey EE, Smith WL, Pringle KC, Soper RT, Franken EA. Balloon dilatation of esophageal stenosis in children. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1988;150:639-642. |

| 103. | Kozarek RA, Patterson DJ, Ball TJ, Gelfand MG, Jiranek GE, Bredfeldt JE, Brandabur JJ, Wolfsen HW, Raltz SL. Esophageal dilation can be done safely using selective fluoroscopy and single dilating sessions. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;20:184-188. |

| 104. | Fan Y, Song HY, Kim JH, Park JH, Ponnuswamy I, Jung HY, Kim YH. Fluoroscopically guided balloon dilation of benign esophageal strictures: incidence of esophageal rupture and its management in 589 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197:1481-1486. |

| 105. | Chao HC, Chen SY, Kong MS. Successful treatment of congenital esophageal web by endoscopic electrocauterization and balloon dilatation. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:e13-e15. |