Published online Apr 26, 2024. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v16.i4.353

Peer-review started: December 21, 2023

First decision: February 3, 2024

Revised: February 17, 2024

Accepted: March 15, 2024

Article in press: March 15, 2024

Published online: April 26, 2024

Processing time: 125 Days and 14.3 Hours

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an acute respiratory infection caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). SARS-CoV-2 infection typically presents with fever and respiratory symptoms, which can progress to severe respiratory distress syndrome and multiple organ failure. In severe cases, these complications may even lead to death. One of the causes of COVID-19 deaths is the cytokine storm caused by an overactive immune res

Core Tip: As the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic normalizes, developing efficient treatments is critical to reducing the strain on the healthcare system. We summarize the various current treatments for COVID-19 and the mechanisms of damage caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Through the comparison to existing treatments, we find that stem cell therapy has more research value. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) and their derived exosomes (MSC-Exo) have homing, immunomodulatory, and tissue repair abilities. They can reduce lung injury and inhibit pulmonary fibrosis. We summarized the clinical trials in recent years, analyzed the safety and effectiveness of MSC and MSC-Exo treatment from various aspects such as mechanism of action and therapeutic effect, and provided substantial theoretical support for their clinical application.

- Citation: Hou XY, Danzeng LM, Wu YL, Ma QH, Yu Z, Li MY, Li LS. Mesenchymal stem cells and their derived exosomes for the treatment of COVID-19. World J Stem Cells 2024; 16(4): 353-374

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-0210/full/v16/i4/353.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4252/wjsc.v16.i4.353

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is an enveloped, positive-single-stranded genomic RNA virus[1]. The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by the SARS-CoV-2 infection spread rapidly worldwide. Droplets mainly transmit COVID-19, and infected individuals can show mild to severe symptoms of respiratory diseases, such as fever, cough, malaise, dyspnea, etc. Some infected individuals may have clinical symptoms such as muscle pain, headache, loss of smell or taste, expectoration, diarrhea, etc. In severe cases, patients may develop pneumonia and respiratory failure, and even lead to death[2]. Recent findings highlight that multiple COVID-19 infections significantly increase the risks associated with mortality, length of hospital care, and enduring complications in various organ systems during both the immediate and long-term recovery phases[3], underscores the persistent health risk of COVID-19, exacerbated by the lack of comprehensive, effective treatments. However, numerous research institutions believe there is still hope for ending the pandemic. Contemporary therapeutic strategies against COVID-19 predominantly fall into two categories: One includes the host’s reaction to infection, encompassing treatment of inflammation, thrombosis, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and modulation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system; the other involves direct actions against the virus, including the use of antiviral drugs, recovery plasma, and antibody therapies[4]. In addition, in some countries and communities, traditional herbs and vitamins, among other health supplements, are commonly used to tackle COVID-19[5]. Despite the widespread adoption of these treatment methods, they still have their limitations. Here, we have compared the various treatment approaches for COVID-19 (Table 1). The comparison in Table 1 demonstrates that stem cell therapy shows greater research potential and therapeutic value compared to existing treatment options.

| Treatment categories | Classification | Application examples | Countries and regions | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| Targeting the host response | Inflammation | Dexamethasone reduces overreaction of the immune system and lowers inflammation[118] | Widely used globally | Reduces the immune system’s overreaction and lowers inflammation, decreasing mortality rates | There are uncertainties and individual variabilities, which may entail potential risks and are constrained to early disease intervention |

| Thrombosis | Heparin is used to prevent thrombosis and protect the cardiovascular system[119,120] | Reduces the risk of thrombosis and improves the prognosis of patients | Blood clotting needs to be carefully monitored to reduce the risk of bleeding | ||

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | Oxygen therapy aids in supporting respiratory function and enhancing oxygenation[121,122] | Improves severe hypoxemia | There are side effects on healthy organs and tissues | ||

| Activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system | ACE inhibitors alter ACE2 expression or activity[123,124] | Reduces the viral invasion by SARS-CoV-2, thus improving survival and reducing lung inflammation and injury | There is a potential risk of causing or exacerbating hypotension, hyperkalemia, or kidney damage | ||

| Multi-targeted stem cell therapy | Stem cell therapy promotes the repair of damaged tissue, regulates immune responses, and reduces inflammation[125] | Decreases the inflammatory response, lowers the risk of cytokine storms, and promotes the repair of damaged tissues, thereby improving outcomes in severe cases | Further research is necessary to ascertain the safety, efficacy, optimal timing for administration, and appropriate dosages | ||

| Targeting viruses | Blocking viral replication | Artemisia annua, through its direct inhibition of viral RNA polymerase[5] | Madagasca (Africa) | Offers a potential for shorter hospitalization | The use of unproven artemisinin therapy raises concerns about the emergence of drug-resistant malaria. For drugs currently in use, there should also be extensive randomized controlled trials to assess their effectiveness and safety in the population |

| The active metabolite of remdesivir reduces genome replication by inhibiting RNA-dependent RNA polymerase[4] | Widely used globally | ||||

| Blocking viral access to host cells | Plasma from convalescent patients containing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2[126-128] | United States, United Kingdom, Germany, China, Brazil, Africa, etc. | Provides immediate immune support and benefits critically ill patients who do not have other appropriate treatment options. Early administration of recombinant monoclonal antibody is effective in preventing hospitalization | However, challenges include high variability in antibody levels and quality, the need to match blood types, and the risk of transmission of other pathogens. The neutralizing activity of recombinant monoclonal antibodies is readily lost as new virus variants emerge | |

| Passive administration of pathogen-specific antibodies has been employed to control viral infections[129-132] | |||||

| Targeting improves immunity | Nutritional supplement | Vitamin C enhances immunity by stimulating interferon production and lymphocyte proliferation and enhancing neutrophil phagocytosis[133] | Widely used globally | Enhances immunity | Further research is needed to fully understand its safety, efficacy, optimal administration timing, and dosage |

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are distinguished by their intrinsic capacity for self-renewal and the ability to differentiate in multiple directions. As pluripotent stem cells, they have the potential to slow aging and restore balance to organs affected by trauma, or various pathological conditions[6]. MSCs effectively regulate immune responses in clinical research settings, as demonstrated in both animal models and human clinical trials. The application of MSCs is vital in mitigating hyperactive immune reactions and repairing pathological damage[7]. A significant aspect of the therapeutic mechanism of MSCs involves MSC-derived exosomes (MSCs-Exo), classified as a specific category of paracrine extracellular vesicles[8]. These exosomes encapsulate a range of bioactive molecules, including cytokines, growth factors, signaling lipids, mRNAs, and regulatory microRNAs (miRNAs), essential for intercellular communication and the intercellular transfer of these bioactive elements[9]. MSCs-Exo has similar biological functions with MSCs, such as repairing and regenerating tissues and regulating the immune system, suggesting the feasibility of MSCs and MSCs-Exo in the treatment of acute lung injury as well as their prospective application in the healing of COVID-19[10,11]. This paper reviews the potential mechanisms of MSCs and MSCs-Exo in the treatment of COVID-19, reviews and compares the research progress of different sources of MSCs for the remedy of COVID-19, and looks forward to the safety and effectiveness of MSCs targeting these organs through different delivery pathways, which provides the theoretical basis for the subsequent related therapeutic options.

An exacerbating factor in the progression of COVID-19 is an overactive immune response, characterized by cytokine release syndrome[12]. Specifically, SARS-CoV-2 infects alveolar epithelial cells by mediating membrane fusion via angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor and transmembrane protease serines and induces an immune response accompanied by the accumulation of immunoreactive cells, leading to cytokine storm (CS), resulting in lung tissue damage, repair disruption, and subsequent multi-organ dysfunction[13,14]. ACE2 expression in other organs, such as the kidney, liver, and heart, contributes to respiratory and multi-organ complications in critically ill patients[15]. Histological analyses of patients who died from severe COVID-19 showed that lung lesions, characterized by extensive alveolar epithelial damage and inflammatory cell infiltration, were a consequence of viral infection. These pathological changes are often associated with intense systemic reactions and can lead to death[16-18].

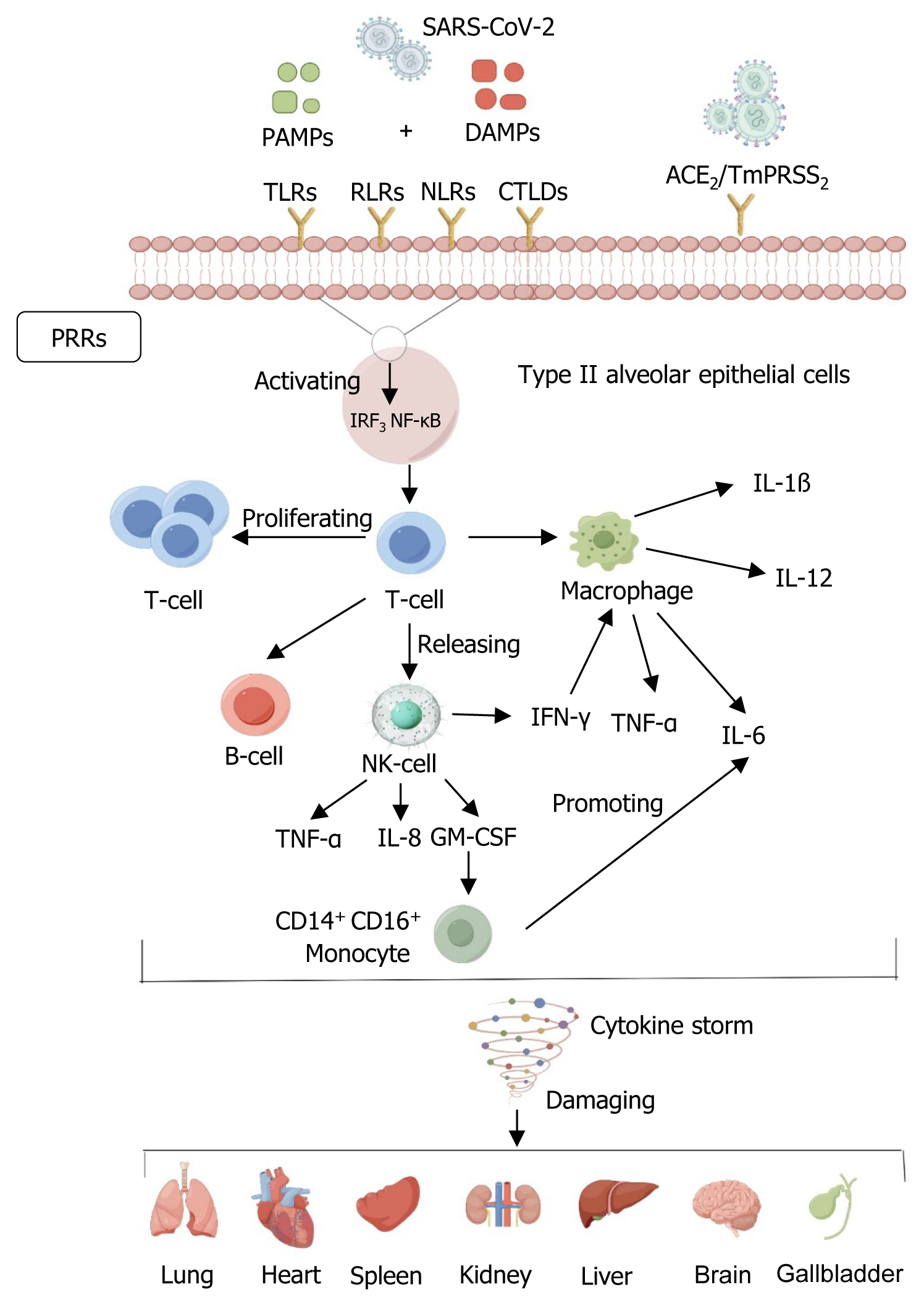

Coronaviruses bind to host receptors, mediating membrane fusion and virus penetration through their S proteins[19]. In the host response to COVID-19 infection, two primary immune mechanisms are involved: Innate immunity, which identifies and neutralizes antigens, and adaptive immunity, activated upon direct antigenic interaction. A foundational aspect of the natural immune response is the detection of pathogenic entities by pathogen-associated molecular patterns. This detection catalyzes the activation of the nuclear factor kappa-B pathway and the interferon (IFN) regulatory factor 3 pathway. Activation of these pathways is critical for the induction of type I and type III IFN expression and for synthesizing pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines[20]. An effective immune response, as described above, successfully eliminates the virus and improves the patient’s clinical symptoms. However, SARS-CoV-2 evades host immune system surveillance through multiple mechanisms, particularly IFN- and ISG-mediated killing[21]. Studies have shown that SARS-CoV-2 can inhibit the early production of IFN, delaying the immune response at the early stages of infection. This delayed response allows the virus more time to replicate and spread, exacerbating infection[22]. When the host eventually develops an immune response, the immune system needs to generate a stronger response to clear the virus because of the increased viral load. This excessive immune response may release large amounts of inflammatory factors, including interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-2, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-17, and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. The massive release of these inflammatory factors prompts T lymphocytes and monocyte macrophages to migrate from the peripheral blood to the site of infection, which may cause a massive uncontrolled immune response that may eventually lead to CS[23] (Figure 1). The specific immune system also exhibits marked dysregulation in COVID-19, with one of the most striking features being the massive depletion of CD4+ T and CD8+ T cells that correlates with the severity of the disease, with activated CD4+ T cells typically differentiating into type 1 T helper cells, which exhibit antiviral activity through the secretion of cytokines such as IFN-γ, and follicular helper T cells, which assist the B cells in forming germinal centers to ensure the long-term maintenance of antibodies in the circulatory system and the persistence of the immune response. In contrast, CD8+ T cells potentially kill virus-infected target cells directly[24,25]. Research has indicated that individuals suffering from severe COVID-19 cases tend to have elevated concentrations of IL-2, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor compared to those with mild to moderate infections[26,27]. In addition, the number of lymphocytes (CD4+ and CD8+ cells), especially CD8+ T cells, continued to decrease substantially in severe patients, but the number of neutrophils increased[28]. Consequently, these results suggest that by closely observing CS dynamics, medical professionals could identify patients at an elevated risk of progressing to severe COVID-19 at an early stage.

COVID-19 is an acute infectious disease that can invade various organs, including the respiratory system. The pa

| Organ system | Primary change | |

| Lung tissue | Acute interstitial pneumonia occurs along with diffuse alveolar damage. The lung tissue shows macrophage infiltration, hyaline membrane formation, and alveolar wall edema. Microvascular involvement includes hyaline thrombosis, hemorrhage, vascular endothelial edema, and immune cell infiltration[134] | + |

| Cardiovascular system | Degeneration and necrosis of some cardiomyocytes, interstitial congestion and oedema, and infiltration by a few monocytes, lymphocytes, and neutrophils are observed. The nucleic acid test for novel coronavirus is occasionally positive. Endothelial cell detachment and endothelial or whole-layer inflammation are present in small blood vessels in significant parts of the body, accompanied by mixed intravascular thrombosis, thromboembolism, and infarction in the corresponding areas. The microvessels of major organs are prone to hyaline thrombosis[135] | + |

| Liver | The liver is enlarged with dark red hepatocyte degeneration and focal necrosis with neutrophil infiltration; hepatic sinusoids are congested, and lymphocyte and monocyte infiltration and microthrombosis are observed in the confluent area[136] | + |

| Gallbladder | The gallbladder is highly filled, and the mucosal epithelium is detached[137] | + |

| Kidney | The renal glomeruli exhibit congestion and occasional segmental fibrinoid necrosis; proteinaceous exudates can be observed within the glomerular lumens. Proximal renal tubular epithelial degeneration, partial necrosis, and desquamation are present, while casts can be found in the distal tubules. The renal interstitium is congested, with microthrombi formation noted[138] | + |

| Brain | Congestion, oedema, degeneration of some neurons, ischaemic changes and detachment, phagocytosis, and satellite phenomena are found. Infiltration of monocytes and lymphocytes in the perivascular space is observed[139] | |

| Testicle | Varying degrees of reduction in the number of spermatogenic cells and degeneration of Sertoli and Leydig cells are observed[140] | + |

| Adrenal gland | Cortical cell degeneration, focal hemorrhage, and necrosis are observed[141] | |

| Esophageal, gastric, and intestinal mucosal epithelium | There is variable degeneration, necrosis, and detachment observed, accompanied by the infiltration of monocytes and lymphocytes in the lamina propria and submucosa[142,143] | + |

| Organ system | Secondary change | |

| Spleen | The spleen shrinks. The white marrow is atrophic, with a decreased number of lymphocytes and some cell necrosis; the red marrow is congested and focally hemorrhagic, macrophages are proliferated, and phagocytosis is observed in the spleen; anemic infarcts of the spleen are easily found. Immunohistochemical staining shows decreased spleen CD4+ T and CD8+ T cells[144] | + |

| Lymph nodes | The lymphocyte count is reduced, and necrosis is found. Immunohistochemical staining shows decreased CD4+ T and CD8+ T cells in the spleen and lymph nodes. Lymph node tissues may be positive for novel coronavirus nucleic acid detection in macrophages[145] | + |

| Bone marrow | Hematopoietic cells are either hyperplastic or reduced in number, with an increased granulocyte-red ratio[146] |

A growing number of studies have reported the reparative role of MSCs and MSCs-Exo in repairing tissue and organ damage, as well as respiratory and pulmonary infections. These studies further affirm that the autologous and allogeneic sources of MSC products achieve optimal therapeutic outcomes across a broad spectrum of clinical diseases related to immunomodulation[35].

MSCs were first identified in bone marrow by Fridenshteĭn[36]. In addition to bone marrow, MSCs are present in various sources, are easy to obtain, isolate, and culture, have high amplification capacity, and remain stable after multiple passages in vitro[37]. Belonging to the category of pluripotent stem cells originating from the mesoderm, MSCs possess the capability for multi-directional differentiation. They can transform into various types of tissue cells, including adipose, bone, cartilage, muscle, and neural cells when subjected to specific inducing conditions either in vivo or in vitro[38]. MSCs also have potent tissue-repairing, anti-inflammatory, and immune-modulating functions. MSCs can be imported into the body through multiple pathways, which is not easy to cause immune rejection[39]. In addition, studies have shown that MSCs derived from different human tissues do not express ACE2, suggesting that MSCs are naturally immune to SARS-CoV-2 and that MSCs with low or no HLA expression are resistant to SARS-CoV-2 infection[40], and that this low-immunogenicity enables them to evade host immune responses, which is an important basis for their therapeutic efficacy. In addition, leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF) released by MSCs can counteract the CS during viral pneumonia. However, its expression cannot counteract the disease’s damage[41,42]. To enhance the effectiveness of LIF, “LIFNano” nanotechnology, which can amplify the efficacy of LIF by a factor of 1000, has been developed. This significant increase in efficacy can effectively suppress CS associated with COVID-19[43]. Therefore, MSCs present a viable treatment for COVID-19, offering regulation of the hyperactivated immune response and aiding in the recovery from lung damage.

MSCs are extracted and isolated from diverse tissues, such as bone marrow, adipose tissue, dental structures, amniotic fluid, the umbilical cord, liver, tendons, and heart[44]. Given their derivation from specific stromal vascular fractions of tissues, these MSCs display variability in aspects like gene expression profiles, phenotypic traits, growth dynamics, and their differentiation potential[45-47]. Factors such as the extraction site, as well as the MSCs’ quality and quantity, influence the composition of growth factors, cytokines, extracellular vesicles, and secreted bioactive elements in the regenerative context, which in turn plays a critical role in shaping the therapeutic outcomes in clinical settings[48]. Selecting an appropriate MSC source is pivotal for the success of their application in treating various diseases. Here, we compare the advantages and disadvantages of MSC therapy for COVID-19 from different sources (Table 4), we believe that umbilical cord MSCs (UC-MSCs) can be prioritized for COVID-19 treatment, but the exact molecular mechanism of UC-MSCs for COVID-19 treatment still needs to be explored in the future[49].

| Types | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| UC-MSCs | Prevent fibrosis and restore the oxygenation index and down-regulated CS in critically ill COVID-19 hospitalized patients; readily available and rapidly expanded to clinically required numbers without raising ethical issues and with minimal allograft rejection[147,148] | More extensive randomized trials and phase III clinical trials of UC-MSCs are still needed to investigate the exact molecular mechanisms of UC-MSCs in treating COVID-19 patients |

| BM-MSCs | Inhibit CS[149] | Adverse events such as low cryopreservation survival, cell product heterogeneity, immunogenicity, and thrombus generation, which have been observed with BM-MSCs products, as well as the low number of MSCs in bone marrow aspirates and the invasive nature of the process of obtaining MSCs have also prevented the generalization of BM-MSCs[150-152] |

| PL-MSCs | Higher amounts of CD106 are expressed because surface markers such as CD106 and CD54 are important for immunizing MSCs through cell-to-cell contact[153] | Differences in autologous or allogeneic preparation protocols and ethical concerns about PL-MSCs[154] |

| ADSCs | Rich tissue sources and tissue collection methods are simple[155] | Some severe side effects have been shown, such as three cases of vision loss after patients with AMD received bilateral intravitreal injections of autologous adipose tissue-derived stem cells at a stem-cell clinic[156] |

Although cell therapy has many advantages in treating COVID-19, it faces numerous challenges. First, specific cytokines secreted by MSCs, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), may induce tumors. Second, since MSCs are highly sensitive to harsh cellular microenvironments (e.g., inflammation), their survival rate is low after tran

Exosomes are small vesicles containing complex RNAs and proteins with lipid bilayer membrane structure, which can carry and transfer a wide range of proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids related to their cellular origin, acting as signaling molecules to other cells and thus participating in the important regulation of cellular exercises, influencing the physiological activities of target cells, and mediating biological effects such as inter-cellular signaling and immunomodulation[53]. MSCs-Exo and MSCs share similar functions, including the repair and regeneration of tissues and the regulation of body immunity[54]. Several studies have demonstrated that MSCs-Exo may inhibit CSs and reduce tissue damage conditions, including ARDS, acute lung injury, and fibrosis[55]. MSCs-Exo group had similar therapeutic outcomes and efficacy to MSCs for treating pulmonary fibrosis after COVID-19 and may be a novel therapy for long-term pulmonary sequelae[56]. MSCs-Exo also enhanced macrophage phagocytosis and significantly diminished TNF-α and IL-8 secretion, thereby ameliorating lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury in mice[57]. Furthermore, many of these MSC-Exos are carriers of miRNAs, which are integral in controlling important cell functions such as cellular proliferation, programmed cell death, and the responses of the host immune system[58,59]. Therefore, MSCs-Exo could serve as optimal carriers for delivering specific antiviral medications in treating COVID-19[60]. However, the widespread use of exosomes faces numerous challenges. With the large variety of MSCs, it is unclear whether there are discrepancies between exosomes of different origins and how much these differences affect the immunomodulatory effects. In addition, these multifaceted challenges include selecting appropriate isolation and purification methods, preparing high-quality, homogeneous, large quantities of exosomes, and optimizing exosome storage conditions[61]. In addition, the issue of efficiently delivering drugs to target cells needs to be addressed. These difficulties must be overcome to utilize the potential of exosomes in COVID-19 treatment fully. MSCs-Exo origin has shown promising applications in various diseases.

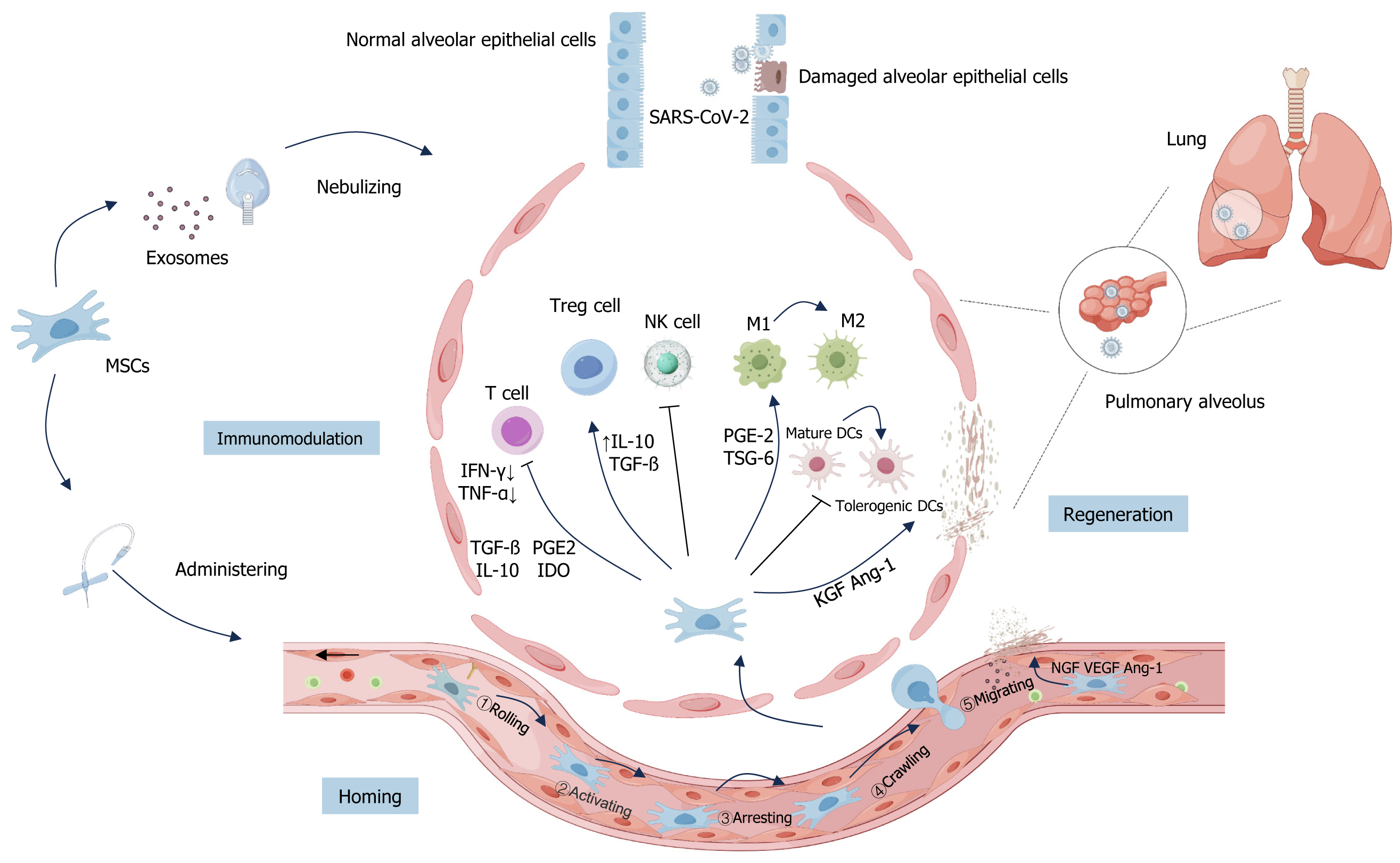

As mentioned earlier, the generation of CS caused an uncontrolled immune response in patients, and the subsequent symptoms of ARDS and acute lung injury were the main reasons for the aggravation of COVID-19 patients’ conditions and even death. While MSCs and MSCs-Exo have the ability of immune regulation and tissue repair and regeneration, they can be homed to the injury site to alleviate lung injury and inhibit lung fibrosis in the treatment of COVID-19, and have a positive effect on the improvement of the respiratory function and the prognosis of the patients with COVID-19 (Figure 2).

Homing of MSCs: The “homing effect” of MSCs allows them to localize to areas of injury due to various causes, which is a prerequisite for the therapeutic action of stem cells[62]. MSCs can be administered via systemic routes or directly at specific sites. These two pathways guide the systemic homing and non-systemic homing of MSCs, respectively[63]. In non-systemic homing, MSCs are transplanted locally into damaged tissue, and chemokine gradients guide MSCs to migrate to the injury site accurately. On the other hand, systemic homing involves a more complex biological process, including five key steps: Rolling, activating, arresting, crawling, and migrating. This series of steps enables MSCs to migrate from the blood to distant sites of injury efficiently, which can be accelerated with the help of drugs or may occur through the natural entry of MSCs into the bloodstream. Each step has its unique biological significance, which collectively promotes the efficient transport and localization of MSCs in the body[62]. With this “homing effect”, MSCs are delivered to the damaged site and play an active role in repair and regeneration[64].

Kosaric et al[65] showed that Ly6Chi cells could not be converted to the Ly6Clo phenotype in injured tissues, resulting in delayed tissue repair. Depletion of Ly6c+ macrophages can be observed in wounds where bone marrow MSCs (BM-MSCs) appeared through a systemic homing effect after intravenous infusion. This study suggests that MSCs can migrate to the injury site through systemic homing and promote the injury-healing process, providing a theoretical basis for the clinical treatment of COVID-19 with MSCs. In addition, it has been shown that patients with COVID-19 may develop intestinal infections with gastrointestinal symptoms of varying severity, including abdominal pain, diarrhea, consti

Homing of MSCs-Exo: In addition, Alvarez-Erviti et al[68] concluded that functional small interfering RNAs could be efficiently delivered to the mouse brain by systemic injection of targeted exosomes. This finding implies that MSCs-Exo may also retain the homing properties of MSCs. However, this property of MSCs-Exo has not yet been systematically studied, and deeper exploration is still needed to broaden therapeutic ideas against COVID-19 in the future.

Immunomodulatory role of MSCs: MSCs have a bi-directional immunoregulatory mechanism, exerting an immune-boosting effect when the immune response is low and inhibiting the immune response when the immune response is strong. When MSCs migrate towards the injury site, they exert their immunosuppressive properties to inhibit the development of CS, which is achieved through the paracrine pathway of MSCs that releases large amounts of soluble cytokines, growth factors, chemokines, and other mediators or directly interacts with immune cells. Key factors associated with these processes are numerous, including IL-6[69], transforming growth factor β (TGF-β)[70], prostaglandin E2[71], indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase[72] and nitric oxide synthase (iNOS)[73]. Also, MSCs play a critical role in modulating local and systemic immune responses, influencing a range of in vivo effector functions[74]. These functions encompass enhancing macrophage polarization, suppressing the activation and proliferation of T-cells, fostering the growth of regulatory T-cells (Tregs), and reducing the cytotoxic activity of natural killer cells, among others[75,76]. Among them, MSCs can promote macrophage polarization from the M1 subtype to the M2 subtype, this process can be mediated by cytokines (e.g., TGF-β) secreted by MSCs[57,77,78]. MSCs can also regulate T cell function in various ways, such as secreting soluble proteins (e.g., programmed death ligand 1) to inhibit the proliferation and activation of CD4+ T cells and inducing them to be hyporesponsive[79,80].

It was found that MSCs cultured in a serum-free medium significantly inhibited bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis by enhancing the induction of Tregs into the lungs and correcting the dysregulated cytokine balance[81]. In addition, MSCs can regulate the activity and differentiation of immune cells and inhibit immune responses. In a mouse model of acute lung injury, infusion of MSCs reduced the number of M1-type macrophages, inhibited neutrophil chemokine secretion, reduced the enrichment of CD38+ and CD11b+ CD38+ monocyte-derived dendritic cells in the lungs, and inhibited antigen presentation processes[82].

Immunomodulatory role of MSCs-Exo: MSCs can also promote macrophage polarization from the M1 subtype to the M2 subtype by secreting miRNA-carrying exosomes (e.g., miR-182)[57,77,78]. On the other hand, MSCs-Exo promotes the proliferation and immunosuppressive capacity of Tregs by up-regulating the inhibitory cytokines IL-10 and TGF-β, attenuating the inflammatory response, and decreasing the level of overactive immune response in patients with COVID-19[79,80]. In addition, recently published studies have shown that MSCs-Exo induces M2 polarization in macrophages by down-regulating iNOS and up-regulating arginase 1 antibody[83] to ameliorate the adverse consequences of SARS-CoV-2 infection, which predicts a great potential for the application of MSCs-Exo in immune modulation.

Regenerative repair and antifibrotic effects of MSCs: In the context of critical COVID-19 patients, some present with significant alveolar and pulmonary vascular endothelial cell damage, accompanied by varying degrees of pulmonary fibrosis. MSCs promote the repair and regeneration of the damaged alveolar epithelium by secreting multiple cytokines and trophic factors[84,85]. MSCs can restore the function and integrity of damaged alveolar epithelium by secreting paracrine factors such as TGF-α, TGF-β, hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), epithelial growth factor, and angiopoietin 1[86]. Gong et al[87] demonstrated that MSCs co-cultured with alveolar epithelium in vitro could successfully differentiate into type II alveolar epithelial cells and repair the damaged alveolar structure. In addition, the decrease of alveolar permeability to proteins caused by intravenous infusion of MSCs given to ARDS patients may be mediated by the reduction of alveolar epithelial damage, which also provides biological evidence for treating lung injury with MSCs[88].

In addition, MSCs produce various pro-angiogenic factors that activate both extrinsic and intrinsic coagulation pathways, promote blood coagulation, and facilitate neovascularization in healing tissues. The latest clinical findings suggest that pulmonary vascular endothelial cells can also be essential as therapeutic targets during SARS-CoV-2 infection[89]. MSCs can release VEGFs to form neovascularization and improve endothelial function. Several studies have confirmed the ability of skin-derived ABCB5+ MSCs to activate the pro-angiogenic hypoxia-inducible factor-1 pathway under low oxygen conditions. This activation significantly enhanced the transcription of VEGF by approximately quadrupling its level. Consequently, this upsurge in transcription was observed to substantially boost VEGF protein secretion, effectively contributing to repairing damaged blood vessels[85].

In addition to the damage of alveolar and pulmonary vascular endothelial cells, the lungs of some patients with severe COVID-19 also show different degrees of pulmonary fibrosis symptoms. MSCs can significantly reduce pulmonary fibrosis and improve lung structure and function. It was found that MSCs secreted antifibrotic proteins and improved lung collagen deposition and lung fibrosis scores in mice in a bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis model[90]. The above studies illustrate that MSCs inhibit fibrosis, but whether MSCs can be used in COVID-19-associated pulmonary fibrosis triggered by multiple factors and the specific improvement effect still needs to be verified by more in vivo experiments and a more mature clinical evaluation system.

Regenerative repair and antifibrotic effects of MSCs-Exo: MSCs-Exo also contributes to the recovery of alveolar epithelial and endothelial cells, maintains vascular barrier integrity, repairs damaged lung tissues, and reduces pulmonary fibrosis. MSCs-Exo contains all the same immunomodulatory and pro-angiogenic factors as MSCs, and the immunomodulation mediated by MSCs-Exo is similar to or even superior to that of MSCs[91]. In addition, highly expressed miR-145 and related proteins within the exosomes also significantly promoted the functional maintenance and regeneration of injured lung tissues, thereby facilitating lung injury repair and providing a more promising therapeutic approach for COVID-19[92]. In an experimental lung fibrosis model, growth factors secreted by MSCs through exosomes, such as HGF, showed anti-fibrotic effects. HGF prevents apoptosis of epithelial cells and shows anti-fibrotic effects in an experimental fibrosis model[93]. Therefore, MSCs-Exo represents a potential novel cell-free therapeutic agent for regenerative repair and antifibrosis in regenerative medicine, and its efficacy needs to be explored in future clinical trials.

In addition to the several main mechanisms of action mentioned above for the treatment of COVID-19, there are some other potential mechanisms, such as the antimicrobial effect of MSCs, which also provide new ideas for the treatment of COVID-19. Compared with mild COVID-19 patients, the neutrophil counts in severe patients showed a significant increase at 13-15 d after the onset of the disease, suggesting that severe patients may have a co-infection of bacterial infections and viral infections[94]. Research has demonstrated the vital role of human-derived antimicrobial peptides, integral to the innate immune system, in providing early defense against lung viral infections[95]. MSCs combat pathogenic infections by producing these antimicrobial peptides, a capability that has potential applications in treating severe COVID-19 cases[96]. The antimicrobial actions of MSCs are attributed to the secretion of various cytokines, including LL-37[97], human β-defensin-2 (hBD-2)[98], and lipid carrier protein 2 (Lcn2)[99], among others, and the regulation of immune cell functions. Specifically, MSCs directly eliminate bacteria through LL-37, which interacts with the toll-like receptor-4 signaling pathway, and through Lcn2, which is mediated by hBD-2[98]. MSCs lack phagocytic activity, but when macrophages are reprogrammed from a pro-inflammatory phenotype to an anti-inflammatory phenotype, MSCs stimulate monocyte macrophages to enhance their phagocytosis of bacteria[100] to promote bacterial infection in critically ill patients’ recovery. The antimicrobial effects of MSCs could be utilized as an improved COVID-19 treatment.

MSCs and MSCs-Exo have multiple roles in treating and repairing COVID-19-induced tissue damage, and there is a close relationship between the mechanisms of homing, immunomodulation, regenerative repair, and anti-fibrotic. The unique homing ability and targeted modifications of MSCs can enhance their ability to promote tissue regeneration[101]. When tissues and organs are damaged, MSCs sense and respond to signaling molecules released from damaged tissues, migrate to these damaged areas, and activate the immune system. Next, damaged cells secrete damage-associated molecular patterns and vigilantes, signaling substances that attract leukocytes such as neutrophils, monocytes, dendritic cells, natural killer cells, and T lymphocytes to the injury site. After successfully eliminating the pathogen, the immune cells shift to an immunosuppressive phenotype that contributes to the production and proliferation of immunosuppressive cells to moderate the ongoing inflammatory response[102]. MSCs can promote the repair and regeneration of damaged tissues by secreting growth factors and extracellular vesicles. MSCs can differentiate into different types of cells, such as osteoblasts, chondrocytes, or adipocytes, to replace the damaged cells, increase the number of new cells, and repair the damaged tissue structure. In addition, MSCs-Exo is one of the key factors released by MSCs and has similar functions to MSCs. For example, MSCs-Exo can also regulate the activity of receptor cells, promote cell self-repair and tissue regeneration, and accelerate wound repair at the injury site[103]. In summary, multiple mechanisms promote the repair of damaged tissues, which makes MSCs and MSCs-Exo promising to be potent tools for treating COVID-19, autoimmune diseases, trauma, and chronic diseases.

Many clinical trials involving MSCs and MSCs-Exo have demonstrated their effectiveness in treating COVID-19 and related complications. As of November 2023, more than 100 registered clinical trials have investigated the use of MSCs and MSCs-Exo for the treatment of COVID-19, and our study covers 20 of the most recent relevant clinical trials in terms of cell source, dosage administered, and therapeutic efficacy (in terms of clinical symptoms, biomarkers, and lung imaging) (Table 5). Meanwhile, we have preliminarily summarized the general criteria for treating COVID-19 by MSCs and MSCs-Exo based on the relevant clinical trials mentioned above, which mainly include the following aspects.

| No. | Study title | Trial ID | Phase | Indications | Source | Route and time of administration | Dose | Effectiveness of treatment | Number of patients | Ref. | ||

| Clinical symptoms | Cytokine storm biomarkers | Lung image | ||||||||||

| 1 | Effectiveness and safety of normoxic allogenic umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells administered as adjunctive treatment in patients with severe COVID-19 | NCT04333368 | Phase 1 | Severe COVID-19 | NA-UC-MSC | Intravenous infusions, 3 rounds (at days 0, 3, and 6) | 1 × 106/kg | Improved the oxygenation index, oxygen saturation | ↓ESR, CRP | 42 | [104] | |

| 2 | Repair of acute respiratory distress syndrome in COVID-19 by stromal cells (REALIST-COVID Trial): A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial | NCT03042143 | Phase 2 | Moderate and severe ARDS in COVID-19 | ORBCEL-C | Intravenous infusions, 1 round | 400 × 106 cells | Prolonged duration of ventilation, modulated the peripheral blood transcriptome | 60 | [157] | ||

| 3 | Human placenta-derived mesenchymal stem cells transplantation in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) caused by COVID-19 (phase I clinical trial): Safety profile assessment | IRCT20200621047859N4 | Phase 1 | ARDS in COVID-19 | PL-MSC | Intravenous infusions, 1 round | 1 × 106 cells/kg | Not show any adverse events | 20 | [153] | ||

| 4 | Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cell therapy in severe COVID-19: Preliminary results of a phase I/II clinical trial | NCT04445454 | Phase 1/2 | Severe COVID-19 | BM-MSC | Intravenous infusions, 3 rounds (1, 4 ± 1, 7 ± 1) | (1.5-3) × 106 cells/kg | The higher survival rate in the MSC group at both 28 and 60 d | ↓D-dimer | 32 | [158] | |

| 5 | Mesenchymal stromal cell therapy for COVID-19-induced ARDS patients: A successful phase 1, control-placebo group, clinical trial | IRCT20160809029275N1 | Phase 1 | ARDS in COVID-19 | UC-MSC | Intravenous infusions, 3 rounds (1, 3, 5) | 1 × 106 cells/kg | Improved the SpO2/FiO2 ratio | ↓CRP, IL-6, IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-17A; ↑TGF-β, IL-1β, IL-10 | 20 | [159] | |

| 6 | Safety of DW-MSC infusion in patients with low clinical risk COVID-19 infection: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | NCT04535856 | Phase 1 | Low clinical risk COVID-19 | UC-MSC | Intravenous infusions, 1 round | High dose: 1 × 108 cells or low dose: 5 × 107 cells | 9 | [160] | |||

| 7 | Safety and long-term improvement of mesenchymal stromal cell infusion in critically COVID-19 patients: A randomized clinical trial | U1111-1254-9819 | Phase 1/2 | Critical COVID-19 | UC-MSC | Intravenous infusions, 3 rounds (at days 1, 3, and 5) | 5 × 105 cells/kg/round | ↓Ferritin, IL-6, MCP1-CCL2, CRP, D-dimer, and neutrophil levels; | A decrease in the extent of lung damage was observed in the fourth month | 17 | [161] | |

| 8 | Treatment of COVID-19-associated ARDS with mesenchymal stromal cells: A multicenter randomized double-blind trial | NCT04333368 | Phase 2 | ARDS in COVID-19 | UC-MSC | Intravenous infusions, 3 rounds (at days 1, 3 ± 1, and 5 ± 1) | 1 × 106 cells/kg/round | Significant increase in PaO2/FiO2 ratios | 47 | [162] | ||

| 9 | Clinical experience on umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell treatment in 210 severe and critical COVID-19 cases in Turkey | Phase 1 | Severe/critical COVID-19 | UC-MSC | Intravenous infusions, 1 round | (1-2) × 106/kg | Significantly lower mortality, improvements in SaO2 | 210 | [163] | |||

| 10 | Cell therapy in patients with COVID-19 using Wharton’s jelly mesenchymal stem cells: A phase 1 clinical trial | IRCT20190717044241N2 | Phase 1 | Severe COVID-19 | UC-MSC | Intravenous infusions, 3 rounds (at days 0, 3, and 6) | 1.5 × 108 cells/round | ↓Ferritin | 5 | [70] | ||

| 11 | The systematic effect of mesenchymal stem cell therapy in critical COVID-19 patients: A prospective double controlled trial | NCT04392778 | Phase 1/2 | Critical COVID-19 | UC-MSC | Intravenous infusions, 3 rounds (at days 0, 3, and 6) | 3 × 106 cells/kg/round | ↓Ferritin, fibrinogen, and CRP | 30 | [164] | ||

| 12 | Umbilical cord mesenchymal stromal cells as critical COVID-19 adjuvant therapy: A randomized controlled trial | NCT04457609 | Phase 1 | ARDS in COVID-19 | UC-MSC | Intravenous infusions, 1 round | 1 × 106 cells/kg/round | Survival rate was 2.5 times higher in the UC-MSC group than in the control group | ↓IL-6 | 40 | [165] | |

| 13 | Evaluation of the safety and efficacy of using human menstrual blood-derived mesenchymal stromal cells in treating severe and critically ill COVID-19 patients: An exploratory clinical trial | ChiCTR2000029606 | Phase 1 | Severe and critical COVID-19 | Allogenic menstrual blood-derived MSCs | Intravenous infusions, 3 rounds (1, 3, 7) | Total 9 × 107 cells | Significant improvement in dyspnea on days 1, 3, and 5 and significant improvements in SpO2 and PaO2 | Improved the lung condition | 44 | [166] | |

| 14 | Effect of human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells on lung damage in severe COVID-19 patients: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial | NCT04288102 | Phase 2 | Severe COVID-19 | UC-MSC | Intravenous infusions, 3 rounds (at days 0, 3, and 6) | 4 × 107 cells/round | Significant reduction in the proportions of solid component lesion volume | 100 | [147] | ||

| 15 | Mesenchymal stem cells derived from perinatal tissues for treatment of critically ill COVID-19-induced ARDS patients: A case series | IRCT20200217046526N2 | Phase 1 | ARDS in COVID-19 | UC-MSC | Intravenous infusions, 3 rounds (at days 0, 2, and 4) | 2 × 108 cells/round | Reduced dyspnea and increased SpO2 within 2-4 d | ↓TNF-α, IL-8, and CRP. There is no significant difference between the two groups (P > 0.05) | Reduction in ground-glass opacities or consolidation | 11 | [106] |

| 16 | Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells for COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome: A double-blind, phase 1/2a, randomized controlled trial | NCT04355728 | Phase 1/2a | ARDS in COVID-19 | UC-MSC | Intravenous infusions, 2 rounds (at days 0 and 3) | (10 ± 2) × 107 cells/round | Improved patient survival and a shorter time to recovery | ↓GM-CSF, IFN-γ, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, TNF-α, and TNF-β | 24 | [167] | |

| 17 | Human umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cell therapy in patients with COVID-19: A phase 1 clinical trial | NCT04252118 | Phase 1 | Moderate and severe COVID-19 | UC-MSC | Intravenous infusions, 3 rounds (at days 0, 3, and 6) | 3 × 107 cells/round | ↓IL-6, IFN-γ, | Complete fading of lung lesions within 2 wk | 18 | [168] | |

| 18 | Treatment of severe COVID-19 with human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells | ChiCTR2000031494 | Phase 1 | Severe/critical COVID-19 | UC-MSC | Intravenous administration, 1 round | 2 × 106 cells/kg | Improved the weakness, fatigue, shortness of breath, and oxygenation index as early as the third day | ↓CRP, IL-6 | Shorter lung inflammation absorption | 41 | [49] |

| 19 | Nebulization therapy with umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes for COVID-19 pneumonia | ChiCTR2000030261 | Phase 1 | Moderate COVID-19 | MSCs-Exo | Nebulized, twice a day (am 8:30, pm 16:00) for 10 min each | 1 million cells/kg predicted body weight | ↓CRP, IFN-γ, IL-17, ATH 19; ↑NK | Absorption of pulmonary lesions | 7 | [115] | |

| 20 | Nebulized exosomes derived from allogenic adipose tissue mesenchymal stromal cells in patients with severe COVID-19: A pilot study | NCT 04276987 | Phase 2 | Severe COVID-19 | HAMSCs-Exo | Nebulized, consecutively 5 d | 2.0 × 108 nanovesicles | ↓CRP, IL-6, lymphocyte counts, and LDH | Massive infiltration and ground-glass opacity disappeared | 7 | [114] | |

Most of the COVID-19 patients treated with MSCs and MSCs-Exo were moderate to severe, often developed ARDS, and eventually progressed to multiple organ failure. The severity of the disease is not determined by the viral load of SARS-CoV-2 but by the inflammatory response[104]. The abnormal increase in pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in patients with severe COVID-19 indicates a dysfunction in their immune system, necessitating the treatment with MSCs and MSCs-Exo. COVID-19 patients should meet specific inclusion criteria, including age, underlying diseases, and the patient’s immune status, to exclude patients suffering from specific comorbidities or high risk of complications from stem cell therapy. In addition, some studies might choose older patients due to their generally more severe reactions to COVID-19[105].

The collection of MSCs and MSCs-Exo needs to meet ethical and legal requirements and be expanded and prepared in the laboratory to obtain sufficient numbers of cells and exosomes for treatment. In 20 of these clinical trials, 14 used UC-MSCs, 1 used CD362-enriched, umbilical cord-derived MSCs, 1 used placental MSC, 1 used BM-MSCs, 1 used allogenic menstrual blood-derived MSCs, and 2 used MSCs-Exo. These data suggest that UC-MSCs are a significant source for use in clinical trials to treat COVID-19.

The therapeutic dose of MSCs and MSCs-Exo is usually determined based on the patient’s body weight and specific clinical conditions. In Table 5, most clinical trials employed a multi-dose (2-3 times) administration approach, with each dose ranging from 5 × 105 cells/round to 2 × 108 cells/round. In clinical trials involving MSCs-Exo, one study adopted a twice-daily administration (at 8: 30 am and 4: 00 pm), each session lasting 10 min, while another trial implemented a consecutive 5-d dosing regimen, with each dose ranging from 1 × 106 cells/round to 2 × 108 cells/round. Given the prevalent administration of doses up to 2 × 108 cells/round in current clinical trials, we categorize this as a higher dosage range. Consequently, we delve into the efficacy of high-dose therapy and the potential risks associated with even higher dosages. In the phase 1 trial conducted by Hashemian et al[106] focused on treating severe ARDS with MSCs, the findings indicated that administering multiple high-dose (at days 0, 2, and 4, 2 × 108 cells/d) intravenous infusions of prenatal allogeneic MSCs was generally safe and well-tolerated.

Notably, although MSCs treatment of COVID-19 showed potential benefits, the increased cell dose may be ac

Currently, the treatment of COVID-19 by MSCs and MSCs-Exo mainly includes intravenous injection of MSCs and nebulization of MSCs-Exo. Both methods have their advantages and disadvantages. Intravenous infusion of MSCs is typically used for treating systemic diseases or conditions that require circulation through the bloodstream to various parts of the body, such as certain types of autoimmune diseases, inflammatory diseases, tissue injury repair, and some degenerative diseases[75,112]. MSCs can repair multiple organ damage induced by COVID-19. However, since MSCs are live cells, their infusion can trigger immune system responses in the body, leading to varying degrees of side effects like inflammatory reactions and allergic responses. Additionally, MSCs may not be evenly distributed in the body after infusion. In some instances, specific areas affected by a disease may not receive an adequate concentration of cells, resulting in suboptimal therapeutic effects[113]. Primarily, the application of nebulized MSCs-Exo is targeted toward treating respiratory conditions, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, and pulmonary fibrosis[114]. Exosomes can directly target the lungs and upper respiratory tract through nebulization, offering high therapeutic effectiveness for pulmonary diseases. Some studies have performed MSCs-Exo nebulization in patients with mild and severe COVID-19, which promoted the absorption of lung lesions and shortened the length of hospital stay in patients with mild COVID-19[114,115]. Nebulization is a non-invasive method of administration, usually more acceptable to patients. It is proved that MSCs-Exo can be used as a safe and feasible new approach for the treatment of COVID-19[95,96]. However, nebulized MSCs-Exo is limited to treating respiratory system-related diseases, and the mechanism of action of exosomes may not be as broad as that of MSCs, offering more specificity. In summary, the clinical application should be based on the specific conditions of patients and disease characteristics to choose the appropriate treatment.

Patients should receive regular medical monitoring during treatment with MSCs and MSCs-Exo, including respiratory status, oxygen saturation, and lung imaging tests. Regular medical monitoring helps to determine the success of the treatment and further treatment as needed. The study demonstrated that after MSC therapy, significant radiological improvements in lung computed tomography (CT) scans were observed in patients, with a notable reduction in pulmonary complications. Some patients showed almost complete resolution of opacities without residual fibrosis 50 d post-treatment. One patient experiencing acute renal failure, pulmonary edema, and bilateral multiple effusions showed a significant reduction in COVID-19-related turbidity post-treatment[106]. Soetjahjo et al[104] showed that patients treated with UC-MSCs (normoxic-allogenic-UC-MSC) improved oxygenation index and oxygen saturation on day 22 of treatment. The levels of three key inflammatory markers (procalcitonin, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein) were also tracked: C-reactive protein showed a significant reduction in both MSCs and controls after 22 d. Also, this treatment regimen improved oxygenation index and oxygen saturation, contributing to lung healing. Significant improvements were also seen in the levels of biomarkers closely associated with severe and critical COVID-19[104]. A clinical study demonstrated that a mildly ill patient’s first chest CT examination revealed an isolated nodule outside the lower lobe of the left lung. The second examination showed a significant reduction in the density and volume of the nodule after MSCs-Exo nebulization treatment, which promoted the absorption of the lung lesion, did not cause acute allergic or secondary allergic reactions, and shortened the hospitalization time[115]. In summary, we believe using MSCs and MSCs-Exo in COVID-19 patients is effective.

Although MSCs and MSCs-Exo have great potential for the treatment of COVID-19, the controversial nature of using them as emerging agents for clinical therapy remains, such as instability in the quality of different batches of MSCs and MSCs-Exo and uncertainty in predicting effects. In addition, due to the unique properties of MSCs and MSCs-Exo, their manufacturing, transportation, and application processes are significantly different from those of standard drugs. Ensuring rigorous quality control at each stage of these processes is critical to maintaining the integrity and efficacy of these products[97]. Therefore, the Scientific Committee of the International Society for Cellular Therapy emphasized the importance of considering key factors to improve clinical success and gain wider acceptance. Similarly, in China, conducting stem cell trials mandates adherence to the “Guidelines for Quality Control of Stem Cell Preparation and Preclinical Research (for Trial Implementation)” and the “Stem Cell Clinical Research Management Methods”. This ensures that MSC therapeutic trials are performed in compliance with international standards.

Meanwhile, scientists are exploring various innovative drug delivery methods to enhance the clinical application of MSCs and MSCs-Exo. Existing methods of delivering MSCs into the body for therapeutic purposes include direct intracellular internalization of nanocarriers and autologous MSC encapsulation in combination with drug administration. However, the complex intracellular environment may degrade the internalized nanocarriers and affect the physiological properties of the cellular carriers. Several studies have constructed a nanoengineering platform based on MSCs, which solved the problem of nanocarriers being degraded by the bio coupling of MSCs and type I collagenase-modified liposomes loaded with Nidanib (MSCs-Lip@NCAF) and adhered to the surface of MSCs through specific biologic ligand-receptor interactions[116]. Autologous MSC-embedded tissue repair coagulant (Tissucol Duo®) has also been feasible, safe, and potentially clinically effective as a prophylactic alternative to prevent prolonged air leakage after pneumonectomy in high-risk patients[117]. In summary, the combination of MSCs piggybacked with corresponding drugs or the use of MSCs themselves as carrier-embedded drugs also has great therapeutic potential. Especially in the face of a more infectious pandemic with faster viral mutation, the number of clinical trials on the safety and efficacy of COVID-19 treatment worldwide is still far from enough, resulting in the exact efficacy and regulatory mechanisms of MSCs and MSCs-Exo in the clinical treatment of COVID-19 patients with severe illnesses are still in the early stage of exploration. In addition, besides mainly attacking the respiratory tract and lungs, the SARS-CoV-2 virus also affects the heart, kidneys, nervous system, and gastrointestinal tract to varying degrees. To evaluate the safety and effectiveness of MSCs and MSCs-Exo in targeting different organs through various delivery routes, more preclinical and randomized controlled clinical trials are needed. This will help to achieve a better therapeutic effect of MSCs and MSCs-Exo in the treatment of COVID-19 and also provide a more theoretical reference.

With the normalization of the COVID-19 pandemic, developing practical therapeutic approaches is critical to reducing the healthcare system’s stresses. The homing, immunomodulation, regenerative repair, and antifibrotic effects of MSCs and MSCs-Exo promote the repair of damaged tissues, making MSCs and MSCs-Exo promising to be a potent therapeutic tool in the treatment of COVID-19. An in-depth understanding of their therapeutic mechanisms and optimization of the application process are crucial, and future studies should focus on improving the safety and efficacy of these therapeutic regimens to make substantial progress in the fight against COVID-19.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Cell and tissue engineering

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kelleni MT, Egypt S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Zhou Z, Zhu Y, Chu M. Role of COVID-19 Vaccines in SARS-CoV-2 Variants. Front Immunol. 2022;13:898192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chen T, Wu D, Chen H, Yan W, Yang D, Chen G, Ma K, Xu D, Yu H, Wang H, Wang T, Guo W, Chen J, Ding C, Zhang X, Huang J, Han M, Li S, Luo X, Zhao J, Ning Q. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. BMJ. 2020;368:m1091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2289] [Cited by in RCA: 2550] [Article Influence: 510.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 3. | Bowe B, Xie Y, Al-Aly Z. Acute and postacute sequelae associated with SARS-CoV-2 reinfection. Nat Med. 2022;28:2398-2405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 315] [Cited by in RCA: 336] [Article Influence: 112.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Murakami N, Hayden R, Hills T, Al-Samkari H, Casey J, Del Sorbo L, Lawler PR, Sise ME, Leaf DE. Therapeutic advances in COVID-19. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2023;19:38-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 49.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nordling L. Unproven herbal remedy against covid-19 could fuel drug-resistant malaria, scientists warn. [cited 10 February 2024]. Available from: https://www.science.org/content/article/unproven-herbal-remedy-against-covid-19-could-fuel-drug-resistant-malaria-scientists. |

| 6. | Jing J, Feng J, Li J, Zhao H, Ho TV, He J, Yuan Y, Guo T, Du J, Urata M, Sharpe P, Chai Y. Reciprocal interaction between mesenchymal stem cells and transit amplifying cells regulates tissue homeostasis. Elife. 2021;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Abraham A, Krasnodembskaya A. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles for the treatment of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2020;9:28-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yin K, Wang S, Zhao RC. Exosomes from mesenchymal stem/stromal cells: a new therapeutic paradigm. Biomark Res. 2019;7:8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 282] [Article Influence: 47.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Katsuda T, Ochiya T. Molecular signatures of mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicle-mediated tissue repair. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015;6:212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cruz FF, Rocco PRM. Stem-cell extracellular vesicles and lung repair. Stem Cell Investig. 2017;4:78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Li Y, Yin Z, Fan J, Zhang S, Yang W. The roles of exosomal miRNAs and lncRNAs in lung diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2019;4:47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 24.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Oberfeld B, Achanta A, Carpenter K, Chen P, Gilette NM, Langat P, Said JT, Schiff AE, Zhou AS, Barczak AK, Pillai S. SnapShot: COVID-19. Cell. 2020;181:954-954.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 18.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Gustine JN, Jones D. Immunopathology of Hyperinflammation in COVID-19. Am J Pathol. 2021;191:4-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 323] [Cited by in RCA: 360] [Article Influence: 90.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Blot M, Bour JB, Quenot JP, Bourredjem A, Nguyen M, Guy J, Monier S, Georges M, Large A, Dargent A, Guilhem A, Mouries-Martin S, Barben J, Bouhemad B, Charles PE, Chavanet P, Binquet C, Piroth L; LYMPHONIE Study Group. Correction to: The dysregulated innate immune response in severe COVID-19 pneumonia that could drive poorer outcome. J Transl Med. 2021;19:100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sun J, He WT, Wang L, Lai A, Ji X, Zhai X, Li G, Suchard MA, Tian J, Zhou J, Veit M, Su S. COVID-19: Epidemiology, Evolution, and Cross-Disciplinary Perspectives. Trends Mol Med. 2020;26:483-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 401] [Cited by in RCA: 347] [Article Influence: 69.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Edler C, Schröder AS, Aepfelbacher M, Fitzek A, Heinemann A, Heinrich F, Klein A, Langenwalder F, Lütgehetmann M, Meißner K, Püschel K, Schädler J, Steurer S, Mushumba H, Sperhake JP. Dying with SARS-CoV-2 infection-an autopsy study of the first consecutive 80 cases in Hamburg, Germany. Int J Legal Med. 2020;134:1275-1284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 313] [Article Influence: 62.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ackermann M, Verleden SE, Kuehnel M, Haverich A, Welte T, Laenger F, Vanstapel A, Werlein C, Stark H, Tzankov A, Li WW, Li VW, Mentzer SJ, Jonigk D. Pulmonary Vascular Endothelialitis, Thrombosis, and Angiogenesis in Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:120-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4313] [Cited by in RCA: 4062] [Article Influence: 812.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Carsana L, Sonzogni A, Nasr A, Rossi RS, Pellegrinelli A, Zerbi P, Rech R, Colombo R, Antinori S, Corbellino M, Galli M, Catena E, Tosoni A, Gianatti A, Nebuloni M. Pulmonary post-mortem findings in a series of COVID-19 cases from northern Italy: a two-centre descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:1135-1140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 730] [Cited by in RCA: 953] [Article Influence: 190.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Jackson CB, Farzan M, Chen B, Choe H. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2022;23:3-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1831] [Cited by in RCA: 1913] [Article Influence: 637.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Gusev E, Sarapultsev A, Solomatina L, Chereshnev V. SARS-CoV-2-Specific Immune Response and the Pathogenesis of COVID-19. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 52.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kim YM, Shin EC. Type I and III interferon responses in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Exp Mol Med. 2021;53:750-760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 47.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Park A, Iwasaki A. Type I and Type III Interferons - Induction, Signaling, Evasion, and Application to Combat COVID-19. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;27:870-878. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 730] [Cited by in RCA: 678] [Article Influence: 135.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Cao X. COVID-19: immunopathology and its implications for therapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20:269-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 972] [Cited by in RCA: 1118] [Article Influence: 223.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kudlay D, Kofiadi I, Khaitov M. Peculiarities of the T Cell Immune Response in COVID-19. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Diao B, Wang C, Tan Y, Chen X, Liu Y, Ning L, Chen L, Li M, Wang G, Yuan Z, Feng Z, Zhang Y, Wu Y, Chen Y. Reduction and Functional Exhaustion of T Cells in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Front Immunol. 2020;11:827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1687] [Cited by in RCA: 1757] [Article Influence: 351.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Muthuka JK Jr, Oluoch K, Wambura FM, Nzioki JM, Nabaweesi R. HIV and Associated Indicators of COVID-19 Cytokine Release Syndrome: A Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression. Cureus. 2023;15:e34688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Chen G, Wu D, Guo W, Cao Y, Huang D, Wang H, Wang T, Zhang X, Chen H, Yu H, Zhang M, Wu S, Song J, Chen T, Han M, Li S, Luo X, Zhao J, Ning Q. Clinical and immunological features of severe and moderate coronavirus disease 2019. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:2620-2629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2835] [Cited by in RCA: 3416] [Article Influence: 683.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Liu J, Li S, Liu J, Liang B, Wang X, Wang H, Li W, Tong Q, Yi J, Zhao L, Xiong L, Guo C, Tian J, Luo J, Yao J, Pang R, Shen H, Peng C, Liu T, Zhang Q, Wu J, Xu L, Lu S, Wang B, Weng Z, Han C, Zhu H, Zhou R, Zhou H, Chen X, Ye P, Zhu B, Wang L, Zhou W, He S, He Y, Jie S, Wei P, Zhang J, Lu Y, Wang W, Zhang L, Li L, Zhou F, Wang J, Dittmer U, Lu M, Hu Y, Yang D, Zheng X. Longitudinal characteristics of lymphocyte responses and cytokine profiles in the peripheral blood of SARS-CoV-2 infected patients. EBioMedicine. 2020;55:102763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1171] [Cited by in RCA: 1207] [Article Influence: 241.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Asrani P, Hassan MI. SARS-CoV-2 mediated lung inflammatory responses in host: targeting the cytokine storm for therapeutic interventions. Mol Cell Biochem. 2021;476:675-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Bian XW; COVID-19 Pathology Team. Autopsy of COVID-19 patients in China. Natl Sci Rev. 2020;7:1414-1418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Stein SR, Ramelli SC, Grazioli A, Chung JY, Singh M, Yinda CK, Winkler CW, Sun J, Dickey JM, Ylaya K, Ko SH, Platt AP, Burbelo PD, Quezado M, Pittaluga S, Purcell M, Munster VJ, Belinky F, Ramos-Benitez MJ, Boritz EA, Lach IA, Herr DL, Rabin J, Saharia KK, Madathil RJ, Tabatabai A, Soherwardi S, McCurdy MT; NIH COVID-19 Autopsy Consortium, Peterson KE, Cohen JI, de Wit E, Vannella KM, Hewitt SM, Kleiner DE, Chertow DS. SARS-CoV-2 infection and persistence in the human body and brain at autopsy. Nature. 2022;612:758-763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 292] [Cited by in RCA: 527] [Article Influence: 175.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Yao XH, Luo T, Shi Y, He ZC, Tang R, Zhang PP, Cai J, Zhou XD, Jiang DP, Fei XC, Huang XQ, Zhao L, Zhang H, Wu HB, Ren Y, Liu ZH, Zhang HR, Chen C, Fu WJ, Li H, Xia XY, Chen R, Wang Y, Liu XD, Yin CL, Yan ZX, Wang J, Jing R, Li TS, Li WQ, Wang CF, Ding YQ, Mao Q, Zhang DY, Zhang SY, Ping YF, Bian XW. A cohort autopsy study defines COVID-19 systemic pathogenesis. Cell Res. 2021;31:836-846. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 25.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Zou X, Chen K, Zou J, Han P, Hao J, Han Z. Single-cell RNA-seq data analysis on the receptor ACE2 expression reveals the potential risk of different human organs vulnerable to 2019-nCoV infection. Front Med. 2020;14:185-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1286] [Cited by in RCA: 1528] [Article Influence: 305.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Hamming I, Timens W, Bulthuis ML, Lely AT, Navis G, van Goor H. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J Pathol. 2004;203:631-637. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3643] [Cited by in RCA: 4149] [Article Influence: 197.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Dauletova M, Hafsan H, Mahhengam N, Zekiy AO, Ahmadi M, Siahmansouri H. Mesenchymal stem cell alongside exosomes as a novel cell-based therapy for COVID-19: A review study. Clin Immunol. 2021;226:108712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Fridenshteĭn AIa. [Osteogenic stem cells of the bone marrow]. Ontogenez. 1991;22:189-197. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Soukup T, Mokrý J, Karbanová J, Pytlík R, Suchomel P, Kucerová L. Mesenchymal stem cells isolated from the human bone marrow: cultivation, phenotypic analysis and changes in proliferation kinetics. Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove). 2006;49:27-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Fridenshteĭn AIa, Piatetskiĭ-Shapiro II, Petrakova KV. [Osteogenesis in transplants of bone marrow cells]. Arkh Anat Gistol Embriol. 1969;56:3-11. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Heo JS, Choi Y, Kim HS, Kim HO. Comparison of molecular profiles of human mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow, umbilical cord blood, placenta and adipose tissue. Int J Mol Med. 2016;37:115-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in RCA: 340] [Article Influence: 34.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Avanzini MA, Mura M, Percivalle E, Bastaroli F, Croce S, Valsecchi C, Lenta E, Nykjaer G, Cassaniti I, Bagnarino J, Baldanti F, Zecca M, Comoli P, Gnecchi M. Human mesenchymal stromal cells do not express ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and are not permissive to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2021;10:636-642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Quinton LJ, Mizgerd JP, Hilliard KL, Jones MR, Kwon CY, Allen E. Leukemia inhibitory factor signaling is required for lung protection during pneumonia. J Immunol. 2012;188:6300-6308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Foronjy RF, Dabo AJ, Cummins N, Geraghty P. Leukemia inhibitory factor protects the lung during respiratory syncytial viral infection. BMC Immunol. 2014;15:41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Metcalfe SM. Mesenchymal stem cells and management of COVID-19 pneumonia. Med Drug Discov. 2020;5:100019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Samsonraj RM, Raghunath M, Nurcombe V, Hui JH, van Wijnen AJ, Cool SM. Concise Review: Multifaceted Characterization of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Use in Regenerative Medicine. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2017;6:2173-2185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 510] [Cited by in RCA: 517] [Article Influence: 64.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Requicha JF, Viegas CA, Muñoz F, Azevedo JM, Leonor IB, Reis RL, Gomes ME. A tissue engineering approach for periodontal regeneration based on a biodegradable double-layer scaffold and adipose-derived stem cells. Tissue Eng Part A. 2014;20:2483-2492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Lopa S, Colombini A, Stanco D, de Girolamo L, Sansone V, Moretti M. Donor-matched mesenchymal stem cells from knee infrapatellar and subcutaneous adipose tissue of osteoarthritic donors display differential chondrogenic and osteogenic commitment. Eur Cell Mater. 2014;27:298-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Stanco D, Viganò M, Perucca Orfei C, Di Giancamillo A, Peretti GM, Lanfranchi L, de Girolamo L. Multidifferentiation potential of human mesenchymal stem cells from adipose tissue and hamstring tendons for musculoskeletal cell-based therapy. Regen Med. 2015;10:729-743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Costela-Ruiz VJ, Melguizo-Rodríguez L, Bellotti C, Illescas-Montes R, Stanco D, Arciola CR, Lucarelli E. Different Sources of Mesenchymal Stem Cells for Tissue Regeneration: A Guide to Identifying the Most Favorable One in Orthopedics and Dentistry Applications. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 22.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Shu L, Niu C, Li R, Huang T, Wang Y, Huang M, Ji N, Zheng Y, Chen X, Shi L, Wu M, Deng K, Wei J, Wang X, Cao Y, Yan J, Feng G. Treatment of severe COVID-19 with human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;11:361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 235] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 42.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Choudhery MS, Harris DT. Stem cell therapy for COVID-19: Possibilities and challenges. Cell Biol Int. 2020;44:2182-2191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Pittenger MF, Discher DE, Péault BM, Phinney DG, Hare JM, Caplan AI. Mesenchymal stem cell perspective: cell biology to clinical progress. NPJ Regen Med. 2019;4:22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 773] [Cited by in RCA: 1248] [Article Influence: 208.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Lotfy A, AboQuella NM, Wang H. Mesenchymal stromal/stem cell (MSC)-derived exosomes in clinical trials. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2023;14:66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 97.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Kalluri R, LeBleu VS. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science. 2020;367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6920] [Cited by in RCA: 6540] [Article Influence: 1308.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Harrell CR, Jovicic N, Djonov V, Arsenijevic N, Volarevic V. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes and Other Extracellular Vesicles as New Remedies in the Therapy of Inflammatory Diseases. Cells. 2019;8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 531] [Article Influence: 88.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Gardin C, Ferroni L, Chachques JC, Zavan B. Could Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Be a Therapeutic Option for Critically Ill COVID-19 Patients? J Clin Med. 2020;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Yousefi Dehbidi M, Goodarzi N, Azhdari MH, Doroudian M. Mesenchymal stem cells and their derived exosomes to combat Covid-19. Rev Med Virol. 2022;32:e2281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Morrison TJ, Jackson MV, Cunningham EK, Kissenpfennig A, McAuley DF, O'Kane CM, Krasnodembskaya AD. Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Modulate Macrophages in Clinically Relevant Lung Injury Models by Extracellular Vesicle Mitochondrial Transfer. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196:1275-1286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 361] [Cited by in RCA: 564] [Article Influence: 70.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Lindsay MA. microRNAs and the immune response. Trends Immunol. 2008;29:343-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 404] [Cited by in RCA: 445] [Article Influence: 26.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Nahand JS, Vandchali NR, Darabi H, Doroudian M, Banafshe HR, Moghoofei M, Babaei F, Salmaninejad A, Mirzaei H. Exosomal microRNAs: novel players in cervical cancer. Epigenomics. 2020;12:1651-1660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Khalaj K, Figueira RL, Antounians L, Lauriti G, Zani A. Systematic review of extracellular vesicle-based treatments for lung injury: are EVs a potential therapy for COVID-19? J Extracell Vesicles. 2020;9:1795365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Ha DH, Kim HK, Lee J, Kwon HH, Park GH, Yang SH, Jung JY, Choi H, Lee JH, Sung S, Yi YW, Cho BS. Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cell-Derived Exosomes for Immunomodulatory Therapeutics and Skin Regeneration. Cells. 2020;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 264] [Cited by in RCA: 330] [Article Influence: 66.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Yuan M, Hu X, Yao L, Jiang Y, Li L. Mesenchymal stem cell homing to improve therapeutic efficacy in liver disease. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022;13:179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |