Published online Jul 28, 2019. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i28.3798

Peer-review started: April 3, 2019

First decision: May 30, 2019

Revised: June 4, 2019

Accepted: June 22, 2019

Article in press: June 23, 2019

Published online: July 28, 2019

Processing time: 116 Days and 17.9 Hours

Cirrhosis is a major risk factor for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Portal vein thrombosis is not uncommon after splenectomy in cirrhotic patients, and many such patients take oral anticoagulants including aspirin. However, the long-term impact of postoperative aspirin on cirrhotic patients after splenectomy remains unknown.

The main purpose of this study was to investigate the effect of postoperative long-term low-dose aspirin administration on the development of HCC and long-term survival of cirrhotic patients after splenectomy.

The clinical data of 264 adult patients with viral hepatitis-related cirrhosis who underwent splenectomy at the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University from January 2000 to December 2014 were analyzed retrospectively. Among these patients, 59 who started taking 100 mg/d aspirin within seven days were enrolled in the aspirin group. The incidence of HCC and overall survival were analyzed.

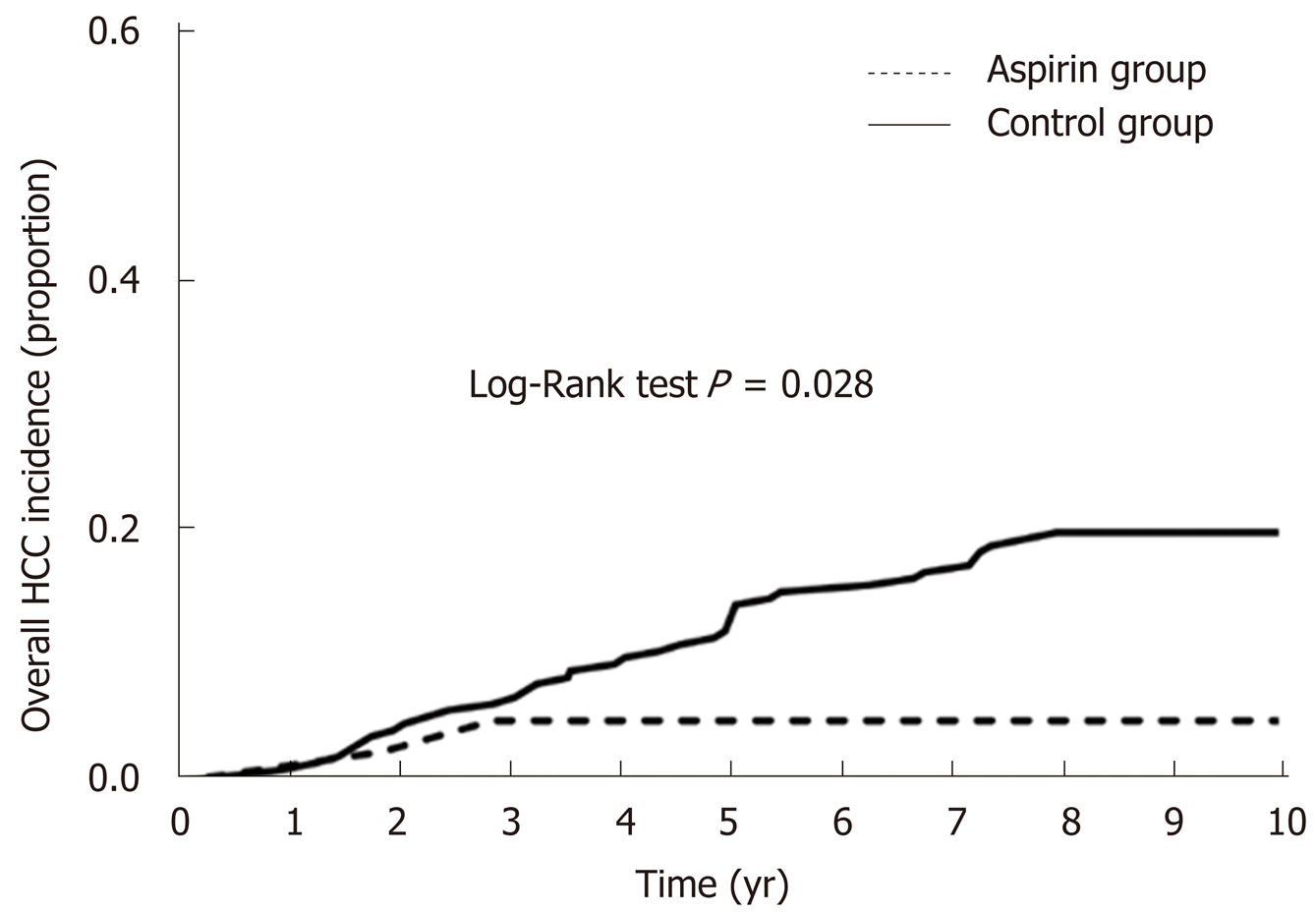

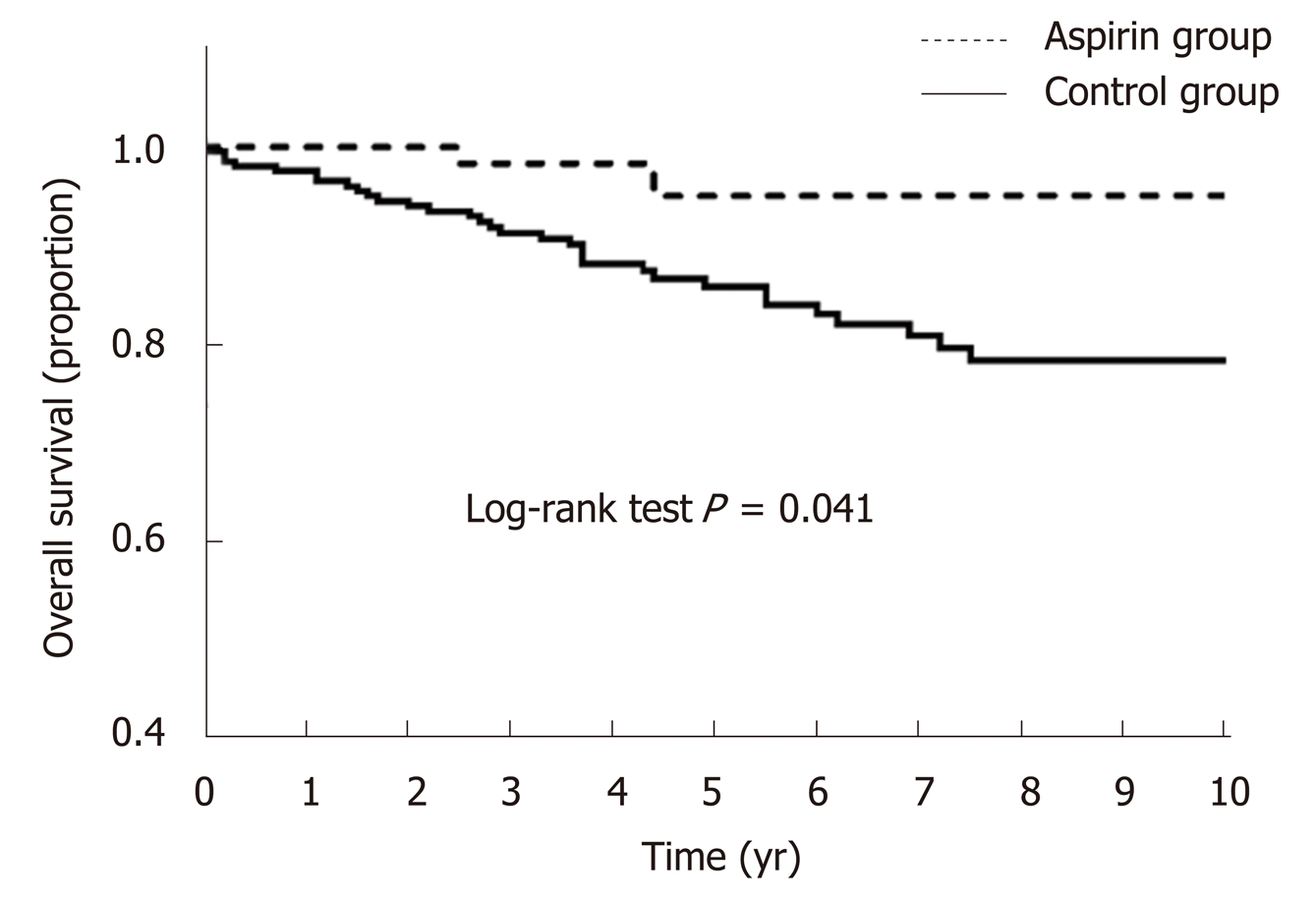

During follow-up, 41 (15.53%) patients developed HCC and 37 (14.02%) died due to end-stage liver diseases or other serious complications. Postoperative long-term low-dose aspirin therapy reduced the incidence of HCC from 19.02% to 3.40% after splenectomy (log-rank test, P = 0.028). Univariate and multivariate analyses showed that not undertaking postoperative long-term low-dose aspirin therapy [odds ratio (OR) = 6.211, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.142-27.324, P = 0.016] was the only independent risk factor for the development of HCC. Similarly, patients in the aspirin group survived longer than those in the control group (log-rank test, P = 0.041). Univariate and multivariate analyses showed that the only factor that independently associated with improved overall survival was postoperative long-term low-dose aspirin therapy [OR = 0.218, 95%CI: 0.049-0.960, P = 0.044].

In patients with viral hepatitis-related cirrhosis, long-term post-splenectomy administration of low-dose aspirin reduces the incidence of HCC and improves the long-term overall survival.

Core tip: Anticoagulant therapy reduces the incidence of post-splenectomy portal thrombosis and improves prognosis by inhibiting thrombus formation. This study was to investigate the effect of postoperative long-term low-dose aspirin therapy on the development of hepatocellular carcinoma and long-term survival of cirrhotic patients after splenectomy. Post-splenectomy long-term administration of low-dose aspirin reduced the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma and improved the long-term overall survival in patients with viral hepatitis-related cirrhosis. Thus, long-term low-dose aspirin therapy should be recommended to cirrhotic patients with hypersplenism after splenectomy.

- Citation: Du ZQ, Zhao JZ, Dong J, Bi JB, Ren YF, Zhang J, Khalid B, Wu Z, Lv Y, Zhang XF, Wu RQ. Effect of low-dose aspirin administration on long-term survival of cirrhotic patients after splenectomy: A retrospective single-center study. World J Gastroenterol 2019; 25(28): 3798-3807

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v25/i28/3798.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i28.3798

Splenectomy, a common surgical treatment for cirrhosis with portal hypertension and hypersplenism, can effectively reduce portal pressure, relieve symptoms, and improve liver function[1,2]. It is often used in patients with viral hepatitis-related chronic liver cirrhosis. However, portal thrombosis is not uncommon after sp-lenectomy, documented at 4.8% to 51.5% of cases[3,4]. Previous studies revealed that portal thrombosis could induce portal hypertension, increase postoperative complications, and result in long-term poor prognosis[5-8]. Therefore, the treatment for portal vein thrombosis after splenectomy is particularly significant.

Anticoagulant therapy reduces the incidence of post-splenectomy portal thrombosis by inhibiting thrombus formation. In this regard, many cirrhotic patients take oral anticoagulants including low-dose aspirin after splenectomy[9,10]. However, the long-term impact of postoperative aspirin on cirrhotic patients after splenectomy remains unknown. The purpose of this study was to investigate the effect of low-dose aspirin therapy on HCC development and long-term overall survival in patients who underwent splenectomy for cirrhosis-related portal vein hypertension and hy-persplenism.

From January 2000 to December 2014, a total of 1662 patients were diagnosed with cirrhosis-related hypersplenism and portal hypertension at the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi'an Jiaotong University. Among them, 295 (17.75%) patients underwent splenectomy, of whom 31 (10.51%) were excluded because they had serious coagulation disorders, cardiovascular diseases, or malignant tumors, or used warfarin or low-molecular-weight heparin after surgery instead of aspirin. The remaining 264 patients were enrolled in this study. Among these patients, 109 took aspirin after surgery. Those who did not start taking it within seven days after surgery, who took less than one year, or who did not follow the doctor's advice were excluded. Finally, 59 patients were included in the aspirin group. This group of patients took aspirin daily at a basic dose of 100 mg. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi'an Jiaotong University and performed in accordance with the provisions of the Helsinki Declaration. No written informed consent was obtained for the retrospective nature of this study.

All clinical variables of these patients were obtained from the electronic medical record system. The general clinical data collected in this study included age, gender, hepatitis status, and underlying concurrent diseases. Laboratory results were collected on the first day after admission, containing routine blood count, liver function, coagulation test, alpha fetoprotein (AFP), and Child-Pugh score. In-traoperative blood loss, spleen size and volume, surgery methods, hospitalization stay, and postoperative complications were also obtained. Portal vein thrombosis was checked by ultrasonography after splenectomy during hospitalization, and anticoagulation information included the initial use of the drugs and detailed name of the drugs.

All patients were followed until October 2017. The median follow-up time was 54 (interquartile range: 40, 87.6) mo. The follow-up content mainly included aspirin drugs, clinical manifestations, laboratory examination, and ultrasound imaging findings. All patients received the relevant follow-up. The overall survival (OS) was recorded from the surgery time to last follow-up, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) occurrence was recorded from the surgery to the last time without tumor. HCC was diagnosed based on imaging results and laboratory tests. To reduce the follow-up bias, two researchers completed the work independently.

Continuous variables are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation or median (min-max). Categorical variables are expressed as frequency and percentage. To calculate the difference between two groups, the Student’s t-test or Wilcoxon test was used for continuous variables and the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical data. For three or more groups, analysis of variance was used. Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and statistical differences were calculated by the log-rank test. If statistical significance was found by univariate analysis, the factor will continue to be calculated through the multivariate log-regression model. All statistical analyzes were performed using PASW Statistics 18.0 software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, United States). Survival curves have been beautified with Graphpad prism 6.0 software (GraphPad Software, Inc. La Jolla, United States). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The demographics and baseline clinical characteristics of the 264 patients are shown in Table 1. The average age of the patients was 45 years (range: 20-67 years), and there were 194 (73.48%) males and 70 (26.52%) females. Among all the patients, 248 (93.94%) had hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, 14 (5.30%) had hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, and 2 (0.76%) had both HBV and HCV infections; 33 (12.50%) had a history of alcohol consumption and 65 (24.62%) had a smoking history; 58 (21.97%) and 21 (7.95%) had hypertension and diabetes, respectively; 71 (26.89%) had a platelet count below 30 (×109/L) at admission. The average values of fibrinogen and alpha fe-toprotein (AFP) at admission were 1.89 g/L (range: 0.60-5.36 g/L) and 10.83 mg/L (range: 0.76-140.90 mg/L), respectively. At admission, 80 (30.30%) cases had Child-Pugh grade A liver function, 165 (62.50%) had Child-Pugh grade B, and 19 (7.20%) had Child-Pugh grade C. The average amount of bleeding during surgery was 425 mL (range: 50-2000 mL). The spleen volume and spleen size were 1410 (range: 156-4896 mm3) and 158 (range: 12-230 mm), respectively. Two hundred and twenty-eight (86.36%) patients underwent open laparotomy and the other 36 (13.64%) patients underwent laparoscopic surgery. The mean length of hospital stay was 27 d (range: 11-125 d). Among these patients, 47 patients (17.80%) developed portal vein thrombosis during hospitalization after splenectomy. A total of 59 patients, including 21 who developed portal vein thrombosis and 38 who did not, were given 100 mg/d aspirin within seven days after surgery for at least one year.

| Clinical characteristic | Median (range)/n (%) |

| Demographic feature | |

| Age (yr) | 45 (20-67) |

| Gender (male:female) | 194:70 |

| Underlying disease | |

| HBV | 248 (93.94) |

| HCV | 14 (5.30) |

| HBV and HCV | 2 (0.76) |

| Coexisting condition | |

| Drinking | 33 (12.50) |

| Smoking | 65 (24.62) |

| Hypertension | 58 (21.97) |

| Diabetes | 21 (7.95) |

| Laboratory results | |

| Leucocytes (109/L) | 2.66 (0.60-59.00) |

| Platelet count (<30 × 109/L) | 71 (26.89) |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 97 (18-175) |

| ALT (>40 U/L) | 91 (34.47) |

| AST (>40 U/L) | 124 (46.97) |

| Albumin (<35 g/L) | 125 (47.35) |

| Total bilirubin (>17 μmol/L) | 184 (69.70) |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 66 (15-188) |

| PT (>17 s) | 79 (29.92) |

| APTT (>45 s) | 77 (29.17) |

| INR (>1.2) | 179 (67.80) |

| Fibrinogen (g/L) | 1.89 (0.60-5.36) |

| AFP (mg/L) | 10.83 (0.76-140.90) |

| Child-Pugh score | |

| Child A | 80 (30.30) |

| Child B | 165 (62.50) |

| Child C | 19 (7.20) |

| Intraoperative and postoperative features | |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | 425 (50-2000) |

| Spleen volume (mm3) | 1410 (156-4896) |

| Spleen size (mm) | 158 (12-230) |

| Surgical method | |

| Laparoscopic surgery | 36 (13.64) |

| Open laparotomy | 228 (86.36) |

| Portal vein thrombosis | 47 (17.80) |

| Postoperative aspirin | 59 (22.35) |

| Length of hospital stay | 27 (11-125) |

In this cohort, 41 (15.53%) patients developed HCC during follow-up and Ka-plan–Meier analysis showed that the incidence of HCC in patients with postoperative aspirin (log-rank test, P = 0.028) was significantly lower than that in patients without aspirin (Figure 1). Univariate and multivariate analyses demonstrated that not taking postoperative aspirin (P = 0.016) was the independent risk factor for the development of HCC after splenectomy (Table 2).

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

| P-value | OR (95%CI) | P-value | OR (95%CI) | |

| Gender (male/female) | 0.067 | 2.348 (0.942-5.853) | 0.088 | 2.287 (0.884-5.919) |

| Age > 60 yr | 0.946 | 1.045 (0.292-3.742) | ||

| Hypertension (yes/no) | 0.222 | 0.628 (0.298-1.325) | ||

| Diabetes (yes/no) | 0.187 | 3.941 (0.514-30.211) | ||

| Drinking (yes/no) | 0.432 | 0.689 (0.276-1.717) | ||

| Smoking (yes/no) | 0.791 | 0.902 (0.421-1.933) | ||

| Platelet count at admission (< 30 × 109/L) | 0.434 | 1.337 (0.646-2.764) | ||

| ALT (> 40 U/L) | 0.543 | 1.237 (0.632-2.459) | ||

| AST (> 40 U/L) | 0.063 | 1.910 (0.966-3.775) | 0.323 | 1.460 (0.690-3.092) |

| Albumin (< 35 g/L) | 0.155 | 0.612 (0.312-1.203) | ||

| Total bilirubin (> 17 μmol/L) | 0.683 | 1.169 (0.553-2.471) | ||

| PT (> 17 s) | 0.581 | 1.221 (0.601-2.477) | ||

| APTT (> 45 s) | 0.297 | 1.452 (0.721-2.924) | ||

| INR (> 1.2) | 0.063 | 2.555 (0.949-6.881) | 0.077 | 2.496 (0.904-6.892) |

| Child-Pugh score | 0.106 | 1.218 (0.959-1.548) | ||

| Surgical method (LS vs OS) | 0.094 | 0.285 (0.066-1.236) | 0.297 | 0.446 (0.098-2.033) |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | 0.184 | 0.998 (0.995-1.001) | ||

| Spleen volume (mm3) | 0.994 | 1.000 (1.000-1.000) | ||

| Spleen size (mm) | 0.129 | 0.993 (0.983-1.002) | ||

| Postoperative early aspirin (yes/no) | 0.010 | 6.696 (1.567-28.616) | 0.016 | 6.211 (1.412-27.324) |

At the end of follow-up, 37 (14.02%) patients died due to end-stage liver diseases or other serious complications. Overall survival rates at 3, 5, and 10 years after splenectomy were 93.18%, 89.77%, and 87.12%, respectively (Table 3). It could be seen that the overall survival of patients in the aspirin group were significantly better than that of the patients who did not receive early postoperative aspirin after surgery (log-rank test, P = 0.041, Figure 2). Next, we used univariate and multivariate analyses to explore factors affecting overall survival after splenectomy. As shown in Table 3, the only factor that was independently associated with overall survival was early postoperative aspirin therapy (P = 0.044). And other factors such as gender, age > 60 years, underlying liver diseases, Child-Pugh score, surgical approach, and spleen volume did not show a statistically significant effect on overall survival.

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

| P-value | OR (95%CI) | P-value | OR (95%CI) | |

| Gender (male/female) | 0.104 | 1.859 (0.896-3.856) | ||

| Age > 60 yr | 0.895 | 1.090 (0.303-3.919) | ||

| Underlying liver disease | ||||

| Hypertension (yes/no) | 0.709 | 1.168 (0.517-2.638) | ||

| Diabetes (yes/no) | 0.491 | 1.497 (0.474-4.726) | ||

| Coexisting condition | ||||

| Drinking (yes/no) | 0.331 | 0.539 (0.156-1.871) | ||

| Smoking (yes/no) | 0.648 | 0.823 (0.356-1.902) | ||

| Platelet count at admission (< 30 × 109/L) | 0.649 | 0.837 (0.388-1.804) | ||

| ALT (> 40 U/L) | 0.061 | 0.510 (0.253-1.030) | 0.495 | 0.710 (0.266-1.897) |

| AST (> 40 U/L) | 0.057 | 0.500 (0.245-1.021) | 0.617 | 0.772 (0.279-2.132) |

| Albumin (< 35 g/L) | 0.012 | 2.583 (1.236-5.398) | 0.737 | 1.158 (0.492-2.724) |

| Total bilirubin (> 17 μmol/L) | 0.260 | 0.620 (0.270-1.425) | ||

| PT (> 17 s) | 0.053 | 0.492 (0.240-1.010) | 0.496 | 0.750 (0.328-1.715) |

| APTT (> 45 s) | 0.907 | 0.955 (0.444-2.054) | ||

| INR (> 1.2) | 0.371 | 0.668 (0.276-1.617) | ||

| Child-Pugh score | 0.008 | 0.422 (0.222-0.800) | 0.181 | 1.728 (0.775-3.857) |

| Surgical method (LS vs OS) | 0.068 | 6.562 (0.871-49.440) | 0.157 | 4.393 (0.566-34.110) |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | 0.131 | 0.999 (0.998-1.000) | ||

| Spleen volume (mm3) | 0.634 | 1.000 (1.000-1.001) | ||

| Spleen size (mm) | 0.563 | 1.003 (0.993-1.013) | ||

| Postoperative early aspirin (yes/no) | 0.017 | 0.170 (0.040-0.731) | 0.044 | 0.218 (0.049-0.960) |

Cirrhotic patients who underwent splenectomy are at a high risk of developing thrombosis[11]. Due to its convenient administration and relatively low bleeding risk, low-dose aspirin is often used after splenectomy[12]. However, the long-term effects of low-dose aspirin in this specific patient population have not been clarified. Here, we found for the first time that long-term low-dose aspirin use after splenectomy significantly reduced HCC incidence and improved overall survival in cirrhotic patients with hypersplenism.

Splenectomy is a routine surgical procedure[1]. Many studies have indicated that splenectomy improved liver function, delayed hepatic fibrosis, corrected cytopenia, and expanded treatment options for the underlying liver disease[13]. Thus, it is commonly used to treat hypersplenism for patients with cirrhosis. Liver cirrhosis is a major risk factor for HCC[14-16]. Hypersplenism is correlated with an increased risk of HCC in patients with post-hepatitis cirrhosis and splenectomy might reduce HCC risk in those patients[17,18]. A recent retrospective study of 2678 cirrhotic patients with hypersplenism showed that 33.0% of cirrhotic patients who did not undergo splenectomy developed HCC, while only 17.3% of those who underwent splenectomy developed HCC[18]. In the current cohort of 264 cirrhotic patients who underwent splenectomy, a total of 41 (15.5%) developed HCC during follow-up, which is consistent with the early report.

Taking a low-dose aspirin daily has been shown to decrease the risk of developing or dying from many types of cancer[19-21]. A recent study[22] on the chemopreventive effect of aspirin on HCC and death due to chronic liver disease showed that any aspirin use at baseline was associated with a reduced risk of both HCC development and mortality. Non-aspirin NSAID users, on the other hand, were not at a reduced risk of developing HCC[20,23]. The anticancer effects of aspirin are mediated through several interconnected mechanisms[24,25]. Aspirin blocks the production of COX1 and COX2, inhibits WNT-β-catenin signaling, and inactivates platelets and the host immune response[26-28]. Chronic or prolonged inflammation can create an environment in which cancer thrives. Chronic viral hepatitis is the major cause of HCC. Immune-mediated inflammatory responses are considered to be the predominant cause of HCC transformation during chronic viral hepatitis. The combined anti-platelet and anti-inflammatory effects of aspirin may specifically prevent inflammation-associated tumorigenesis under such conditions[16,29]. Oral administration of aspirin can be used for long-term treatment of patients at risk of thrombosis. Thus, in cirrhotic patients with hypersplenism, daily low-dose aspirin therapy should be recommended after splenectomy.

The major strength of our study was the long-term follow-up. However, there were also some limitations in the present study. First, the data in this study originated from a single center, therefore the sample size was relatively small and the incidence of postoperative mortality and morbidity was low. For instance, a relatively small proportion of patients died during follow-up, which may have limited the robustness of the multivariable analysis for adjustment for confounding factors. Second, we only considered the long-term use of low-dose aspirin after splenectomy as anticoagulant therapy in this study; however, some patients, especially those who developed portal vein thrombosis, also received other anticoagulants for a short period of time. More data are needed to investigate the long-term effects of other anticoagulants after splenectomy. Third, only viral hepatitis-related cirrhotic patients were enrolled in this study. Therefore, whether long-term low-dose aspirin has the same effect in preventing HCC development in patients with alcohol-related cirrhosis needs to be determined. Moreover, whether taking a low-dose aspirin daily reduces the risk of developing HCC in cirrhotic patients without splenectomy also warrants further investigation. Finally, due to the retrospective nature of this study, the results were subject to some uncontrollable biases, so further prospective studies would be necessary.

In summary, post-splenectomy long-term administration of low-dose aspirin reduces the incidence of HCC and improves the long-term overall survival in patients with viral hepatitis-related cirrhosis. Thus, long-term low-dose aspirin therapy should be recommended to cirrhotic patients with hypersplenism after splenectomy.

Cirrhosis is a major risk factor for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Portal vein thrombosis is not uncommon after splenectomy in cirrhotic patients, and many such patients take oral anticoagulants including aspirin. However, the long-term impact of postoperative aspirin on cirrhotic patients after splenectomy remains unknown.

The motivation of this research was to investigate the effect of low-dose aspirin therapy on HCC development and long-term overall survival in patients who underwent splenectomy for cirrhosis-related portal vein hypertension and hypersplenism.

The main objectives of this study was to investigate the effect of postoperative long-term low-dose aspirin on the development of HCC and long-term survival of cirrhotic patients after splenectomy.

The clinical data of 264 adult patients with viral hepatitis-related cirrhosis who underwent splenectomy at the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University from January 2000 to December 2014 were analyzed retrospectively. Among these patients, 59 who started taking 100 mg/d aspirin within seven days were enrolled in the aspirin group. The incidence of HCC and overall survival were analyzed.

Forty-one (15.53%) patients developed HCC and 37 (14.02%) died due to end-stage liver diseases or other serious complications in this study. Postoperative long-term low-dose aspirin therapy reduced the incidence of HCC from 19.02% to 3.40% after splenectomy. Univariate and multivariate analyses showed that not undertaking postoperative long-term low-dose aspirin therapy was the only independent risk factor for the development of HCC. Similarly, patients in the aspirin group survived longer than those in the control group. Univariate and multivariate analyses showed that the only factor that was independently associated with improved overall survival was postoperative long-term low-dose aspirin therapy.

Post-splenectomy long-term administration of low-dose aspirin reduces the incidence of HCC and improves the long-term overall survival in patients with viral hepatitis-related cirrhosis.

Long-term low-dose aspirin therapy should be recommended to cirrhotic patients with hypersplenism after splenectomy. Further prospective and multi-center studies should be performed to verify our conclusions.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Shrestha B, Weledji E S-Editor: Ma RY L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Kim SH, Kim DY, Lim JH, Kim SU, Choi GH, Ahn SH, Choi JS, Kim KS. Role of splenectomy in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and hypersplenism. ANZ J Surg. 2013;83:865-870. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sugawara Y, Yamamoto J, Shimada K, Yamasaki S, Kosuge T, Takayama T, Makuuchi M. Splenectomy in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and hypersplenism. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;190:446-450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hassn AM, Al-Fallouji MA, Ouf TI, Saad R. Portal vein thrombosis following splenectomy. Br J Surg. 2000;87:362-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Krauth MT, Lechner K, Neugebauer EA, Pabinger I. The postoperative splenic/portal vein thrombosis after splenectomy and its prevention--an unresolved issue. Haematologica. 2008;93:1227-1232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Amitrano L, Guardascione MA, Brancaccio V, Margaglione M, Manguso F, Iannaccone L, Grandone E, Balzano A. Risk factors and clinical presentation of portal vein thrombosis in patients with liver cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2004;40:736-741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 449] [Cited by in RCA: 393] [Article Influence: 18.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ikeda M, Sekimoto M, Takiguchi S, Kubota M, Ikenaga M, Yamamoto H, Fujiwara Y, Ohue M, Yasuda T, Imamura H, Tatsuta M, Yano M, Furukawa H, Monden M. High incidence of thrombosis of the portal venous system after laparoscopic splenectomy: a prospective study with contrast-enhanced CT scan. Ann Surg. 2005;241:208-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sogaard KK, Astrup LB, Vilstrup H, Gronbaek H. Portal vein thrombosis; risk factors, clinical presentation and treatment. BMC Gastroenterol. 2007;7:34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Winslow ER, Brunt LM, Drebin JA, Soper NJ, Klingensmith ME. Portal vein thrombosis after splenectomy. Am J Surg. 2002;184:631-635; discussion 635-636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cheng Z, Yu F, Tian J, Guo P, Li J, Chen J, Fan Y, Zheng S. A comparative study of two anti-coagulation plans on the prevention of PVST after laparoscopic splenectomy and esophagogastric devascularization. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2015;40:294-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Qi X, Han G, Fan D. Management of portal vein thrombosis in liver cirrhosis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11:435-446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | de'Angelis N, Abdalla S, Lizzi V, Esposito F, Genova P, Roy L, Galacteros F, Luciani A, Brunetti F. Incidence and predictors of portal and splenic vein thrombosis after pure laparoscopic splenectomy. Surgery. 2017;162:1219-1230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lai W, Lu SC, Li GY, Li CY, Wu JS, Guo QL, Wang ML, Li N. Anticoagulation therapy prevents portal-splenic vein thrombosis after splenectomy with gastroesophageal devascularization. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:3443-3450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Weledji EP. Benefits and risks of splenectomy. Int J Surg. 2014;12:113-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Axley P, Ahmed Z, Ravi S, Singal AK. Hepatitis C Virus and Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Narrative Review. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2018;6:79-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ayuso C, Rimola J, Vilana R, Burrel M, Darnell A, García-Criado Á, Bianchi L, Belmonte E, Caparroz C, Barrufet M, Bruix J, Brú C. Diagnosis and staging of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): current guidelines. Eur J Radiol. 2018;101:72-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 244] [Article Influence: 34.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ringelhan M, Pfister D, O'Connor T, Pikarsky E, Heikenwalder M. The immunology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Immunol. 2018;19:222-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 440] [Cited by in RCA: 736] [Article Influence: 105.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1264-1273.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2183] [Cited by in RCA: 2508] [Article Influence: 192.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 18. | Lv X, Yang F, Guo X, Yang T, Zhou T, Dong X, Long Y, Xiao D, Chen Y. Hypersplenism is correlated with increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with post-hepatitis cirrhosis. Tumour Biol. 2016;37:8889-8900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wolff RA. Chemoprevention for pancreatic cancer. Int J Gastrointest Cancer. 2003;33:27-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zhao YS, Zhu S, Li XW, Wang F, Hu FL, Li DD, Zhang WC, Li X. Association between NSAIDs use and breast cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;117:141-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Jankowska H, Hooper P, Jankowski JA. Aspirin chemoprevention of gastrointestinal cancer in the next decade. A review of the evidence. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2010;120:407-412. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Sahasrabuddhe VV, Gunja MZ, Graubard BI, Trabert B, Schwartz LM, Park Y, Hollenbeck AR, Freedman ND, McGlynn KA. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, chronic liver disease, and hepatocellular carcinoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104:1808-1814. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chawla YK, Bodh V. Portal vein thrombosis. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2015;5:22-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Drew DA, Cao Y, Chan AT. Aspirin and colorectal cancer: the promise of precision chemoprevention. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16:173-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 293] [Cited by in RCA: 348] [Article Influence: 38.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Alfonso L, Ai G, Spitale RC, Bhat GJ. Molecular targets of aspirin and cancer prevention. Br J Cancer. 2014;111:61-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Eizayaga FX, Aguejouf O, Desplat V, Belon P, Doutremepuich C. Modifications produced by selective inhibitors of cyclooxygenase and ultra low dose aspirin on platelet activity in portal hypertension. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:5065-5070. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Li X, Zhu Y, He H, Lou L, Ye W, Chen Y, Wang J. Synergistically killing activity of aspirin and histone deacetylase inhibitor valproic acid (VPA) on hepatocellular cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;436:259-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Henry WS, Laszewski T, Tsang T, Beca F, Beck AH, McAllister SS, Toker A. Aspirin Suppresses Growth in PI3K-Mutant Breast Cancer by Activating AMPK and Inhibiting mTORC1 Signaling. Cancer Res. 2017;77:790-801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Greten TF, Sangro B. Targets for immunotherapy of liver cancer. J Hepatol. 2017;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |