Published online Jul 14, 2019. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i26.3438

Peer-review started: March 15, 2019

First decision: April 5, 2019

Revised: May 1, 2019

Accepted: May 31, 2019

Article in press: June 1, 2019

Published online: July 14, 2019

Processing time: 121 Days and 18.3 Hours

Neoplasms arising in the esophagus may coexist with other solid organ or gastrointestinal tract neoplasms in 6% to 15% of patients. Resection of both tumors synchronously or in a staged procedure provides the best chances for long-term survival. Synchronous resection of both esophageal and second primary malignancy may be feasible in a subset of patients; however, literature on this topic remains rather scarce.

To analyze the operative techniques employed in esophageal resections combined with gastric, pancreatic, lung, colorectal, kidney and liver resections and define postoperative outcomes in each case.

We conducted a systematic review according to PRISMA guidelines. We searched the Medline database for cases of patients with esophageal tumors coexisting with a second primary tumor located in another organ that underwent synchronous resection of both neoplasms. All English language articles deemed eligible for inclusion were accessed in full text. Exclusion criteria included: (1) Hematological malignancies; (2) Head/neck/pharyngeal neoplasms; (3) Second primary neoplasms in the esophagus or the gastroesophageal junction; (4) Second primary neoplasms not surgically excised; and (5) Preclinical studies. Data regarding the operative strategy employed, perioperative outcomes and long-term outcomes were extracted and analyzed using descriptive statistics.

The systematic literature search yielded 23 eligible studies incorporating a total of 117 patients. Of these patients, 71% had a second primary neoplasm in the stomach. Those who underwent total gastrectomy had a reconstruction using either a colonic (n = 23) or a jejunal (n = 3) conduit while for those who underwent gastric preserving resections (i.e., non-anatomic/wedge/distal gastrectomies) a conventional gastric pull-up was employed. Likewise, in cases of patients who underwent esophagectomy combined with pancreaticoduodenectomy (15% of the cohort), the decision to preserve part of the stomach or not dictated the reconstruction method (whether by a gastric pull-up or a colonic/jejunal limb). For the remaining patients with coexisting lung/colorectal/kidney/liver neoplasms (14% of the entire patient population) the types of resections and operative techniques employed were identical to those used when treating each malignancy separately.

Despite the poor quality of available evidence and the great interstudy heterogeneity, combined procedures may be feasible with acceptable safety and satisfactory oncologic outcomes on individual basis.

Core tip: Esophageal neoplasms manifesting synchronously with other neoplasms of the gastrointestinal tract or solid organs are a unique challenge for the surgeon contemplating their combined resection. Concerns arise about whether patients can tolerate the substantial surgical burden to be exerted on them. Furthermore, the type of esophagectomy required or the choice of conduit for reconstruction when the stomach is to be excised as part of the procedure further complicate the decision-making process. By summing and analyzing existing literature on the topic we aim to determine the best surgical approach depending on the location of the second primary tumor, evaluate the perioperative safety of these procedures and clarify their oncologic outcomes.

- Citation: Papaconstantinou D, Tsilimigras DI, Moris D, Michalinos A, Mastoraki A, Mpaili E, Hasemaki N, Bakopoulos A, Filippou D, Schizas D. Synchronous resection of esophageal cancer and other organ malignancies: A systematic review. World J Gastroenterol 2019; 25(26): 3438-3449

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v25/i26/3438.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i26.3438

Esophageal cancer manifesting as either squamous cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma affects more than 450000 people worldwide and shows an increasing incidence rate over the years[1-4]. Despite innovations in the surgical management of gastrointestinal tract (GI) malignancies, esophageal cancer prognosis remains dismal with 5-year survival rates ranging from 10% to 20%[1,5-7]. Surgery is the mainstay of treatment for esophageal cancer cases amenable to resection[8,9], and represents the best choice for “cure”[10]. Patients with esophageal cancer may present with simultaneous primary malignancies in other organs, such as the stomach, colon, pancreas, liver, kidney and lungs with an estimated incidence of approximately 6%-15%[11-15]. Evidence suggests that this phenomenon may be related to the shared risk factors between esophageal and other GI tract or solid organ malignancies[7,16,17]. Due to their aggressive biologic behavior[18], esophageal carcinomas usually determine survival in these particular patients.

Synchronous resection of both esophageal and second primary malignancy may be feasible in a subset of patients. Although isolated cases have been previously reported, the literature on this topic remains rather scarce. In that context, the objective of this study was to summarize and critically evaluate all available evidence regarding the safety and feasibility of synchronous resection of esophageal carcinoma manifesting simultaneously with another primary organ malignancy. Specifically, we sought to analyze the operative interventions and outcomes of patients undergoing such extensive procedures.

A systematic literature search was performed utilizing Medline/PubMed database until December 2018. This systematic review adhered to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines. The following MESH terms were used in various combinations along with Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT): “Esophageal neoplasms”, “Neoplasms second primary”, “Esophagectomy”, “Neoplasms multiple primary”, “adenocarcinoma”, “squamous cell carcinoma”, “synchronous” and “surgery”. Two independent authors (DP, DS) meticulously searched for potentially eligible articles retrieved after applying the initial search algorithm. Disagreements were resolved by consensus with a third author (DIT). References of the included studies were manually assessed to detect any missing study.

Studies were considered eligible if all of the following criteria were met: (1) Data reported on patients with primary esophageal cancer concurrent with a second primary neoplasm originating from an organ other than the esophagus; (2) Both neoplasms were treated with surgical excision. Exclusion criteria included: (1) Hematological malignancies; (2) Head/neck/pharyngeal neoplasms; (3) Second primary neoplasms in the esophagus or the gastroesophageal junction; (4) Second primary neoplasms not surgically excised; (5) Preclinical; and (6) Non-English studies. In case of overlapping population, only the latest or the most informative studies were included in the final analysis. The main outcomes of interest were the surgical strategy employed in the management of both esophageal and concurrent primary non-esophageal neoplasms as well as the related postoperative outcomes. Descriptive statistics are employed for data presentation.

During pooled data assessment, we used the following definitions: (1) Transthoracic esophagectomy (TTE) incorporates all esophagectomy procedures employing a thoracotomy (namely Transthoracic Two-field Esophagectomy and Transthoracic Three-field Esophagectomy); (2) Non-anatomic gastric resection refers to gastric preserving gastrectomy other than total/subtotal/distal gastrectomy; (3) Anterior resection refers to resection of either the sigmoid colon or the upper part of the rectum.

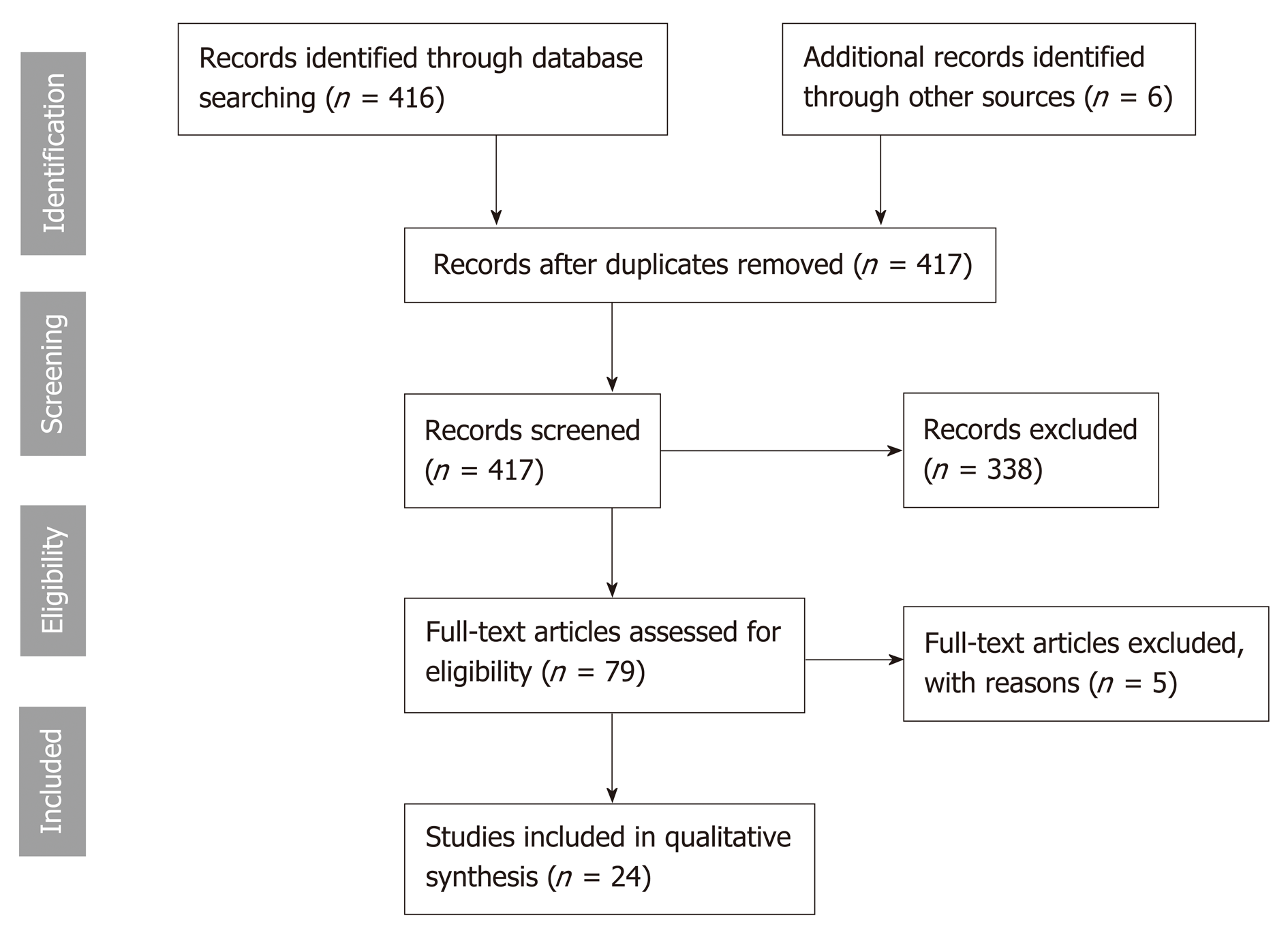

The flowchart of the search strategy is depicted in Figure 1. In brief, the initial search yielded 417 results of which a total of 24 studies met the aforementioned inclu-sion/exclusion criteria[19-42] and thus were included in the analysis. Eligible studies were published between 1994 and 2015. Among them, 6 were single center retrospective studies[19,21,26,36,38,39], while the remaining 18 were case reports or case-series[20,22-25,27-35,37,40-42]. A total of 117 patients with esophageal malignancies coexisting with other primary malignancies were identified. Patient demographics were reported on 44 patients, of which, 37 (84%) were reported to be males and 7 (16%) females. The mean patient age was 59.1 years. Data on the location and histology of the esophageal tumors as well as the coexisting primary tumors are presented in Table 1.

| Author | Year | Number of patients | Esophageal tumor location | Esophageal tumor histology | Second primary tumor location | Second primary tumor histology |

| Kato et al[26] | 1994 | 71 | Upper (n = 4), | N/A | Stomach (n = 71) | Adenocarcinoma |

| Middle (n = 46), | ||||||

| Lower (n = 21) | ||||||

| Isohata et al[24] | 2008 | 1 | Double tumor (lower and middle) | Adenocarcinoma | Stomach | Adenocarcinoma |

| Songping et al[40] | 2013 | 1 | Middle | SCC | Stomach | Adenocarcinoma |

| Kanda et al[42] | 2011 | 1 | Middle | SCC | Stomach | Adenocarcinoma |

| Zhou et al[41] | 2013 | 1 | Lower | SCC | Stomach | Adenocarcinoma and GIST |

| I H et al[38] | 2013 | 4 | Middle (n = 3), | SCC | Stomach | Adenocarcinoma |

| Lower (n = 1) | ||||||

| Chan et al[36] | 2013 | 5 | Proximal (n = 1), | SCC (n = 1), | Stomach | GIST |

| Middle (n = 1), | ||||||

| Adenocarcinoma (n = 4) | ||||||

| Lower (n = 3) | ||||||

| Fukaya et al[37] | 2014 | 1 | Middle | SCC | Stomach and Ampulla of Vater | Adenocarcinoma and small cell carcinoma |

| Mafune et al[31] | 1995 | 1 | Lower | SCC | Ampulla of Vater | Adenocarcinoma |

| Kurosaki et al[29] | 2000 | 1 | Middle | SCC | Pancreatic Head | Adenocarcinoma |

| Jayaprakash et al[25] | 2009 | 1 | GEJ | Adenocarcinoma | Ampulla of Vater | Adenocarcinoma |

| Kim et al[27] | 2011 | 1 | Lower | Adenocarcinoma | Pancreatic Head | Adenocarcinoma |

| Gyorki et al[22] | 2011 | 1 | Middle | Adenocarcinoma | Pancreatic Head | Neuroendocrine carcinoma |

| Fekete et al[21] | 1994 | 12 | N/A | SCC | Lung | N/A |

| Lindeman et al[30] | 2007 | 1 | Middle | SCC | Lung | SCC |

| Ishii et al[23] | 2008 | 2 | Middle (n = 1), | SCC | Lung | Adenocarcinoma |

| Lower (n = 1) | ||||||

| Wang et al[39] | 2012 | 3 | Middle (n = 1), | SCC | Lung | SCC (n = 1), Adenocarcinoma (n = 2) |

| Lower (n = 2) | ||||||

| Motoori et al[32] | 2001 | 1 | Middle | SCC | Rectum | Adenocarcinoma |

| Akiyama et al[35] | 2015 | 1 | Middle | SCC | Colon & Liver | Adenocarcinoma and HCC |

| Kobayashi et al[28] | 2000 | 2 | Middle (n = 1), | SCC | Kidney | Clear cell carcinoma |

| Lower (n = 1) | ||||||

| Liano et al[20] | 2007 | 1 | Lower | SCC | Kidney | Clear cell carcinoma |

| De Hingh et al[19] | 2007 | 1 | N/A | Adenocarcinoma | Kidney | Renal cell carcinoma |

| Vilcea et al[34] | 2010 | 1 | Middle | SCC | Kidney | Urothelial |

| Nagahama et al[33] | 1996 | 2 | Middle (n = 2) | SCC | Liver | HCC |

Stomach: A total of 85 patients (71% of the entire cohort) had concurrent neoplasms of the esophagus and the stomach. Histology of gastric cancer yielded adenocarcinomas in 75 patients and gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) in the remaining 10 patients. Regarding the type of esophagectomy employed, 83 patients underwent a TTE, one patient underwent a transhiatal esophagectomy (THE) while another one underwent esophagectomy via a thoracoabdominal approach. In the same patient group, 26 total gastrectomies were reported, followed by a reconstruction using either a colonic conduit (n = 23) or a jejunal (n = 3) limb. The remaining 59 patients underwent gastrectomies that preserved part of the stomach, such as non-anatomic gastric resections (n = 53), distal gastric resection (n = 2) or underwent tumor excision by endoscopic submucosal dissection (n = 4). In each of these patients the stomach was utilized as a conduit for restoration of gastrointestinal continuity after esophagectomy. Preoperative diagnosis of the second primary neoplasm was available in 91% of the patients. A single minor (Clavien-Dindo II) anastomotic leak was observed; however, 4 cases of perioperative mortality were encountered (Table 2). A two-stage procedure was employed in one patient. During the follow-up period, 43 deaths were recorded (Table 3), of which 35 were attributed to esophageal cancer recurrence and 8 to gastric carcinoma recurrence. Median patient follow-up (as reported in 5 out of 8 total studies) was 15 mo.

| Second primary tumor in stomach | |||||||

| Author | Number of cases | Age (mean) | Type of surgery | Anastomotic leaks | Perioperative deaths | ||

| Esophagus | Stomach | Esophageal substitute | |||||

| Kato et al[26] | n = 71 | 64 | TTE (n = 70) | Non-anatomic resection (n = 46) | Stomach (n = 46) | N/A | n = 3 |

| THE (n = 1) | Total gastrectomy (n = 25) | Colon (n = 22) | n = 1 | ||||

| Jejunum (n = 3) | |||||||

| Isohata et al[24] | n = 1 | 70 | TTE (n = 1) | Non-anatomic resection (n = 1) | Stomach (n = 1) | n = 0 | n = 0 |

| Songping et al[40] | n = 1 | 65 | TAB (n = 1) | Distal gastrectomy (n = 1) | Stomach (n = 1) | n = 0 | n = 0 |

| Kanda et al[42] | n = 1 | 57 | TTE (n = 1) | Distal gastrectomy (n = 1) | Stomach (n = 1) | n = 1 | n = 0 |

| Zhou et al[41] | n = 1 | 77 | TTE (n = 1) | Non-anatomic resection (n = 1) | Stomach (n = 1) | N/A | N/A |

| I H et al[38] | n = 4 | 65 | TTE (n = 4) | ESD (n = 4) | Stomach (n = 4) | n = 0 | n = 0 |

| Chan et al[36] | n = 5 | 69 | TTE (n = 5) | Non-anatomic resection (n = 5) | Stomach (n = 5) | N/A | n = 0 |

| 1Fukaya et al[37] | n = 1 | 69 | TTE (n = 1) | Total gastrectomy (n = 1) | Colon (n = 1) | n = 12 | n = 0 |

| Second primary tumor in pancreas/ampulla of Vater | |||||||

| Esophagus | Pancreas /ampullary | Esophageal substitute | |||||

| Mafune et al[31] | n = 1 | 64 | TTE (n = 1) | PD (n = 1) | Colon (n = 1) | n = 1 | n = 0 |

| Kurosaki et al[29] | n = 1 | 72 | THE (n = 1) | PPPD (n = 1) | Stomach (n = 1) | n = 0 | n = 0 |

| Jayaprakash et al[25] | n = 1 | 62 | TTE (n = 1) | PD (n = 1) | Jejunum (n = 1) | n = 0 | n = 0 |

| Kim et al[27] | n = 1 | 65 | THE (n = 1) | PD (n = 1) | Jejunum (n = 1) | n = 0 | n = 0 |

| 1Gyorki et al[22] | n = 1 | 58 | TTE (n = 1) | PPPD (n = 1) | Colon (n = 1) | N/A | N/A |

| 1Fukaya et al[37] | n = 1 | 69 | TTE (n = 1) | PD (n = 1) | Colon (n = 1) | n = 1 | n = 0 |

| Second primary tumor in lung | |||||||

| Esophagus | Lung | Esophageal substitute | |||||

| Fekete et al[21] | n = 12 | N/A | TTE (n = 12) | Pneumonectomy (n = 1) | Stomach (n = 12) | n = 1 | n = 1 |

| Bilobectomy (n = 1) | |||||||

| Lobectomy (n = 9) | |||||||

| Segmentectomy (n = 1) | |||||||

| Lindeman et al[30] | n = 1 | 60 | TTE (n = 1) | Lobectomy (n = 1) | Stomach (n = 1) | n = 0 | n = 0 |

| 1Ishii et al[23] | n = 2 | 57 | TTE (n = 2) | Segmentectomy (n = 1) | Stomach (n = 2) | n = 1 | n = 0 |

| Wang et al[39] | n = 3 | 65 | TTE (n = 3) | Bilobectomy (n = 1) | Stomach (n = 3) | n = 0 | n = 0 |

| Lobectomy (n = 2) | |||||||

| Second primary tumor in colon/rectum | |||||||

| Esophagus | Colon/rectum | Esophageal substitute | |||||

| Motoori et al[32] | n = 1 | 75 | N/A | AR (n = 1) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 1Akiyama et al[35] | n = 1 | 73 | TTE (n = 1) | AR (n = 1) | Stomach (n = 1) | n = 0 | n = 0 |

| Second primary tumor in kidney | |||||||

| Esophagus | Kidney | Esophageal substitute | |||||

| Kobayashi et al[28] | n = 2 | 61 | TTE (n = 2) | Nephrectomy (n = 2) | Stomach (n = 2) | n = 1 | n = 0 |

| Liano et al[20] | n = 1 | 64 | TTE (n = 1) | Nephrectomy (n = 1) | Stomach (n = 1) | n = 0 | n = 0 |

| De Hingh et al[19] | n = 1 | 69 | THE (n = 1) | Nephrectomy (n = 1) | Stomach (n = 1) | n = 0 | n = 0 |

| 1Vilcea et al[34] | n = 1 | 56 | TTE (n = 1) | Nephrectomy (n = 1) | Stomach (n = 1) | n = 1 | n = 0 |

| Second primary tumor in liver | |||||||

| Esophagus | Liver | Esophageal substitute | |||||

| Nagahama et al[33] | n = 2 | 75 | TTE (n = 2) | Right posterior sectionectomy (n = 2) | Stomach (n = 2) | n = 0 | n = 0 |

| 1Akiyama et al[35] | n = 1 | 73 | TTE (n = 1) | Bisegmentectomy (n = 1) | Stomach (n = 1) | n = 0 | n = 0 |

| Author | Number of patients | Death from esophageal recurrence (%) | Death fromsecond primary recurrence (%) | |

| Second primary in stomach | ||||

| Kato et al[26] | n = 71 | n = 32 (45) | n = 8 (11) | |

| Isohata et al[24] | n = 1 | n = 0 | n = 0 | |

| I H et al[38] | n = 4 | n = 1 (25) | n = 0 | |

| Chan et al[36] | n = 5 | n = 2 (40) | n = 0 | |

| Fukaya et al[37] | n = 1 | n = 0 | n = 01 | |

| Kanda et al[42] | n = 1 | n = 0 | n = 0 | |

| Total | n = 83 | n = 35 (42) | n = 8 (10) | |

| Second primary in pancreas/ampulla of Vater | ||||

| Mafune et al[31] | n = 1 | n = 0 | n = 0 | |

| Kurosaki et al[29] | n = 1 | n = 0 | n = 0 | |

| Jayaprakash et al[25] | n = 1 | n = 0 | n = 0 | |

| Fukaya et al[37] | n = 1 | n = 0 | n = 1 (100)1 | |

| Total | n = 4 | n = 0 | n = 1 (25) | |

| Second primary in lung | ||||

| Lindeman et al[30] | n = 1 | n = 0 | n = 0 | |

| Ishii et al[23] | n = 2 | n = 0 | n = 0 | |

| Total | n = 3 | n = 0 | n = 0 | |

| Second primary in colon/rectum | ||||

| Motoori et al[32] | n = 1 | n = 0 | n = 0 | |

| Akiyama et al[35] | n = 1 | n = 0 | n = 0 | |

| Total | n = 2 | n = 0 | n = 0 | |

| Second primary in kidney | ||||

| Kobayashi et al[28] | n = 2 | n = 0 | n = 0 | |

| Liano et al[20] | n = 1 | n = 0 | n = 0 | |

| Total | n = 3 | n = 0 | n = 0 | |

| Second primary in liver | ||||

| Nagahama et al[33] | n = 2 | n = 1 (50) | n = 0 | |

| Akiyama et al[35] | n = 1 | n = 0 | n = 0 | |

| Total | n = 3 | n = 1 (33) | n = 0 | |

Pancreas/ampulla of Vater: A total of 6 patients (5% of the entire cohort) presented with a second primary malignancy in the pancreas or ampullary region. Four cases of pancreatic or ampullary adenocarcinomas were documented, while the remaining two cases consisted of a neuroendocrine carcinoma and a small cell carcinoma. In this subgroup of patients (Table 2), treatment consisted of 4 TTEs and 2 THEs. Furthermore, 4 patients underwent a pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple’s procedure) followed by restitution of gastrointestinal continuity using either a colonic (n = 2) conduit or a jejunal (n = 2) limb. The remaining 2 patients received a pylorus preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy with subsequent reconstruction by means of an esophagogastrostomy (n = 1) or a colonic conduit (n = 1). There was one case of an esophageal anastomotic leak and one Grade B (according to the ISGPS definition) pancreatic fistula with no reported perioperative deaths. A two-stage procedure was employed in two patients. Preoperative diagnosis of the pancreatic and periampullary tumors was available in all cases. Follow-up monitoring of these patients was available in 4 out of 6 studies and was significant for a single death due to recurrent ampullary neoplasia (Table 3). Median follow-up was reported to be 12.5 mo.

Lung: A total of 18 patients (15% of the entire cohort) were preoperatively diagnosed with a second primary malignancy of the lung. All patients were treated with a TTE. In addition, lung directed therapies consisted of lobectomies (n = 12), segment-ectomies (n = 2), bilobectomies (n = 2) and pneumonectomy (n = 1). A two-stage procedure was employed in two patients. There was one recorded case of postoperative mortality and two anastomotic leaks (Table 2). A median follow-up period of 10 mo is specified for 3 patients, while a cumulative 11% 5-year survival rate was reported for 12 patients.

Colon/rectum: Only two patients (1% of the analytic cohort) had a second primary colorectal malignancy. The surgical approach for these cases was a TTE combined with sigmoidectomy (n = 1) and an unspecified esophagectomy, combined with an anterior rectal resection (n = 1). A two-stage procedure was employed in one patient. The diagnosis of both malignancies was made preoperatively in both patients. After a median follow-up period of 9 mo both patients were reported to be in good health with no signs of disease recurrence.

Kidney: A total of 5 patients (5% of the analytic cohort) had a kidney neoplasm coexisting with an esophageal cancer. Radical nephrectomy (n = 3) combined with either a THE (n = 1) or a TTE (n = 4) were employed; preoperative diagnosis was available in every case. Two cases of postoperative anastomotic leak were described in these studies (Table 2). A two-stage procedure was employed in one patient. Follow-up data were available for 3 patients, which revealed no deaths or recurrences after a median 34 mo.

Liver: Three patients (2% of the entire cohort) had esophageal carcinoma concurrent with hepatocellular carcinoma. These patients underwent TTE, combined with either a posterior sectionectomy (n = 2) or a liver segmentectomy (n = 1). No anastomotic leaks or postoperative mortality was reported; diagnoses of concurrent malignancies were made preoperatively (Table 2). A two-stage procedure was employed in a single patient. A median follow-up period of 17 mo was reported with one case of death due to recurrence of esophageal carcinoma (Table 3).

Coexisting primary neoplasms of the esophagus and other organs present a unique oncologic challenge that complicates surgical decision-making due to the lack of practice guidelines. Suzuki et al[43] postulated that synchronous resection of such neoplasms does indeed provide a benefit to survival but despite this initial report, evidence regarding the management of such patients remains rather scarce, as yet. The current study is important because we sought to critically evaluate the existing literature on the surgical approaches and operative outcomes of patients diagnosed with synchronous primary neoplasms. By employing a systematic search of the literature, we identified a total of 117 patients with concurrent neoplasms in the stomach, pancreas, ampulla of Vater, lung, colon/rectum, kidney and liver. Collectively, the data suggested that synchronous resection was safe, feasible and associated with low perioperative mortality (stomach: 4/84, lung: 1/18, pancreas: 0/6, colon/rectum: 0/2, kidney: 0/5, liver: 0/3). In addition, long-term outcomes of such patients were shown to be determined by the natural history of the esophageal malignancy when synchronous gastric, lung, colorectal, renal and liver cancers were encountered. In contrast, pancreatic cancer may be the main determinant of patient long-term survival when presenting simultaneously with esophageal carcinomas.

The majority of the patient pools (72%) had a second primary neoplasm located in the stomach which was histologically defined as adenocarcinoma in 75 cases and as GIST in 10 cases. A TTE combined with total gastrectomy was performed in 26 patients[26,37]. Gastrointestinal reconstruction for these patients was performed using either a colonic conduit (n = 23)[26,37] or a jejunal limb (n = 3)[26]. No anastomotic leaks were reported for these patients, however one patient died in the postoperative period[26] due to unspecified complications. These procedures, although complex, present a viable solution with acceptable long-term outcomes in cases where the stomach in its entirety needs be removed[44,45]. It should be noted that these procedures, in addition to being technically demanding for the surgeon, exert a substantial impact on the physiology of the patient. To overcome this obstacle, non-anatomic gastric resections (i.e., partial or wedge resections) combined with either a transthoracic (n = 57) or a transhiatal (n = 1) esophagectomy were usually employed[24,26,36,41], followed by a reconstruction utilizing a conventional gastric pull-up. Interestingly, the 46 patients presented in the study by Kato et al[26] underwent gastric preserving gastrectomies despite the probability of a compromised oncologic outcome. In the same study, a comparison of surgical outcomes between patients undergoing total gastrectomy versus patients undergoing a gastric preserving procedure seemed to favor the gastric preserving group, while maintaining comparable long-term survival outcomes between the two groups[26]. Nevertheless, the patient baseline tumor characteristics differed significantly between the compared groups and consequently the results of this study should be interpreted with caution. Three further studies[38,40,42] presented outcomes of patients treated with either distal gastrectomy[40,42] or endoscopic mucosal dissection of early gastric cancer[38]. Both approaches were safe and sufficient from an oncologic perspective for the specific subsets of patients in which they were applied. Finally, six patients were diagnosed with GISTs removed by means of a gastric wedge resection, a procedure that is considered sufficient for these particular neoplasms, taking into account their low malignant potential[36,41]. When a total gastrectomy is mandated, both the colon and the jejunum should be considered reasonable choices for reconstruction, however the surgical team needs to weigh the oncologic advantages against any possible impediment on the patient’s long term quality of life[44,46,47].

Regarding the six patients that were diagnosed with simultaneous esophageal and pancreatic or ampullary malignancies, the choice of esophageal substitute depended on two factors; the need for total gastrectomy (as is the case with concomitant gastric tumors)[37] and the preservation or not of an adequate blood supply to the remnant stomach. Specifically, the preservation of the gastroduodenal artery and its gastroepiploic tributaries is a prerequisite for utilizing the stomach as an esophageal substitute[29]. When the gastroduodenal artery was sacrificed, reconstruction with either a colonic conduit[22,31] or a jejunum limb[25,27] was deemed reasonable, in a similar fashion as in cases of simultaneous esophageal and gastric resections. No patient deaths were reported, although two anastomotic leaks were identified, one from a pancreaticojejunal anastomosis[37] and one from a case in which colonic interposition was used for reconstruction[31].

Eighteen patients were identified having esophageal and lung primary malignancies. For these patients, a transthoracic approach was mandatory in order to address both tumors simultaneously. The choice of side for the thoracotomy was dictated by the side of the lung neoplasia (no bilateral thoracotomies were reported) and gastrointestinal restitution was performed using a gastric conduit. According to the presented data, a left thoracic approach (instead of the standard right thoracotomy), combined with a cervical and abdominal incision might be adequate for excising both concurrent neoplasms and their respective lymphatic basins[39]. Despite the extensive dissection taking place in the thoracic cavity, only one case of a perioperative death[21] and two cases of anastomotic leaks[21,23] were encountered (Table 2). For the remaining 11 patients with concurrent esophageal and colorectal/kidney/ liver neoplasms, the operative technique employed was identical to the one used when treating each malignancy separately. Perioperative mortality was equally low to the previously discussed subgroups of patients, with no deaths being reported and two anastomotic leaks occurring in patients undergoing simultaneous esophagectomy and nephrectomy[28,34].

In order to mitigate the detrimental consequences of a long operative procedure and decrease the devastating consequences of a potential anastomotic leak, several authors opted for a two-staged operative procedure in which GI restitution was accomplished several days after the initial excision stage[22,23,34,35,37]. Establishing the diagnosis of concurrent second primary malignancies before esophageal surgery was possible for the majority of treated patients in our study (113 patients, 96% of the patient pool) thus facilitating the preoperative planning of a combined procedure. Lastly, a major concern when performing simultaneous combined procedures for malignancies is the oncologic long-term outcome. Long term follow-up was available in 16 studies[20,23-26,28-33,35-38,42] (Table 3). In the subgroup of patients with identified gastric second primary neoplasms, out of a total of 85 patients, 34 patients died of esophageal cancer recurrence while 8 died of second primary neoplasm recurrence. The observed lower mortality due to gastric neoplasm recurrences is in part due to the inclusion of GISTs in the analysis. Despite this fact, individual studies demonstrate that esophageal neoplasms are associated with a higher malignant potential than gastric neoplasms[26,36,43], which is often translated to death before gastric cancer relapses. Pooled analysis of the 4 patients with pancreatic and ampullary tumors revealed one case of death from ampullary cancer recurrence, with no deaths attributed to esophageal cancer recurrence. Similarly, esophageal cancer recurrence was the primary cause of death in one of three patients with concurrent neoplasms of the esophagus and liver. No mortality from recurrences was observed in the patients with second primaries found in the lungs, colon/rectum or kidneys.

Utilization of pre-operative and post-operative chemotherapy and radiotherapy was poorly defined in the included studies. Nonetheless, given the aggressive nature of esophageal cancers[43], such patients should be treated in a multidisciplinary setting. The current study had several limitations. First, the small study sample prevents us from drawing accurate and reproducible conclusions regarding the oncologic outcomes of these patients. Second, the considerable interstudy heterogeneity, the inconsistently reported oncologic and surgical outcomes and tumor staging present major limitations in the generalizability of the included results.

In conclusion, data from this systematic review suggested that synchronous resection of esophageal and other primary solid organ malignancy was safe, technically feasible and was associated with acceptable perioperative mortality rates, on individual basis. However, emphasis should be given to the poor quality of the available evidence and the several important limitations of the included studies. Future, well-designed, larger cohort studies will be critical in identifying the optimal therapeutic strategy for patients with synchronous esophageal and organ malignancies.

Esophageal cancer is well known for its lethality and poor prognosis when treated with modalities other than surgery. Esophageal cancer shares many risk factors with other gastrointestinal tract and solid organ neoplasms, a fact which explains why the malignancies may coexist with other tumors of the stomach, colon, liver, pancreas, lung and kidney. This phenomenon is both rare and underreported and when encountered by a treating physician it creates confusion and uncertainty as to what treatment course should be employed, given the lack of relevant practice guidelines. In the present study, by employing a systematic literature review protocol, we sought to elucidate the role of surgical therapy is these patients, the operative techniques applicable in each case and the perioperative and postoperative outcomes that are to be expected.

Summing all available studies concerning patients with coexisting neoplasms of the esophagus and other organs will hopefuly guide patient care and emphasize the need of better and more accurate reporting of such patients.

To identify the operative approaches utilized when synchronously treating neoplasms of the esophagus and the stomach/pancreas/lung/colon/rectum/liver/kidney, their perioperative safety and postoperative outcomes.

We systematically reviewed all existing literature for studies including patients with esophageal cancer and a second primary neoplasm. Studies that included patients who exhibited a second primary neoplasm in an organ other than the head and neck region were included in the analysis. Afterwards, we extracted information pertaining to the intricacies of the operative technique employed, anastomotic leaks, perioperative deaths and neoplasm recurrences.

A total of 23 eligible studies were identified incorporating 117 patients. Eighty five patients had a second primary neoplassm in the stomach and underwent a total gastrectomy (n = 26) with subsequent reconstruction using a colonic (n = 23) or a jejunal (n = 3) conduit or a gastric preserving resection (n = 59) in which a gastric pull-up was used for reconstruction. One anastomotic leak and 4 deaths were recorded in this patient group, whilst follow-up revealed 35 esophageal cancer recurrences and 8 gastric cancer recurrences. Patients that underwent a combined esophagectomy and whipple procedure (n = 6) were reconstructed either by means of a gastric pull-up (n = 1) or a colon/jejunum conduit (n = 5), with 2 anastomotic leaks recorded and no perioperative deaths. Two cases of pancreatic/ampullary carcinoma recurrence were encountered during follow-up. Finaly, the remaining patients (n = 26) with second primary neoplasms in the lung, colon/rectum, kidney and liver had resections identical to those employed in treating each of these neoplasms seperately. Four anastomotic leaks and one case of perioperative mortality were reported. Follow-up was notable only for one case of esophageal cancer recurrence.

The present systematic review supports the safety, efficacy and applicability of combined resections, although the poor quality of included studies limits the strength and generalizability of the results.

Patients with concurrent esophageal and second primary organ neoplasms are a unique category of patients whose survival depends on quick and decisive surgical action. The lack of surgical and oncologic guidelines is therefore a major impediment in treating these unlucky patients. Better reporting of surgical outcomes in a uniform manner may pave the way for future reseach that will eventually help establish clear-cut clinical protocols and optimize therapeutic strategies.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Greece

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ahmad Z, Boukerrouche A, Kosugi S S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: A E-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Malhotra GK, Yanala U, Ravipati A, Follet M, Vijayakumar M, Are C. Global trends in esophageal cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2017;115:564-579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 235] [Article Influence: 29.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Pennathur A, Gibson MK, Jobe BA, Luketich JD. Oesophageal carcinoma. Lancet. 2013;381:400-412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1956] [Cited by in RCA: 1961] [Article Influence: 163.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 3. | Zhang Y. Epidemiology of esophageal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5598-5606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 736] [Cited by in RCA: 747] [Article Influence: 62.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 4. | Arnold M, Soerjomataram I, Ferlay J, Forman D. Global incidence of oesophageal cancer by histological subtype in 2012. Gut. 2015;64:381-387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 944] [Cited by in RCA: 1027] [Article Influence: 102.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Njei B, McCarty TR, Birk JW. Trends in esophageal cancer survival in United States adults from 1973 to 2009: A SEER database analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31:1141-1146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in RCA: 260] [Article Influence: 28.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Murray T, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8283] [Cited by in RCA: 8225] [Article Influence: 483.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Domper Arnal MJ, Ferrández Arenas Á, Lanas Arbeloa Á. Esophageal cancer: Risk factors, screening and endoscopic treatment in Western and Eastern countries. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:7933-7943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 554] [Cited by in RCA: 748] [Article Influence: 74.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (15)] |

| 8. | Polednak AP. Trends in survival for both histologic types of esophageal cancer in US surveillance, epidemiology and end results areas. Int J Cancer. 2003;105:98-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hua Z, Zheng X, Xue H, Wang J, Yao J. Long-term trends and survival analysis of esophageal and gastric cancer in Yangzhong, 1991-2013. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0173896. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sohda M, Kuwano H. Current Status and Future Prospects for Esophageal Cancer Treatment. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;23:1-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Koide N, Adachi W, Koike S, Watanabe H, Yazawa K, Amano J. Synchronous gastric tumors associated with esophageal cancer: A retrospective study of twenty-four patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:758-762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lee JS, Ahn JY, Choi KD, Song HJ, Kim YH, Lee GH, Jung HY, Ryu JS, Kim SB, Kim JH, Park SI, Cho KJ, Kim JH. Synchronous second primary cancers in patients with squamous esophageal cancer: Clinical features and survival outcome. Korean J Intern Med. 2016;31:253-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Nagasawa S, Onda M, Sasajima K, Takubo K, Miyashita M. Multiple primary malignant neoplasms in patients with esophageal cancer. Dis Esophagus. 2000;13:226-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Poon RT, Law SY, Chu KM, Branicki FJ, Wong J. Multiple primary cancers in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: Incidence and implications. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;65:1529-1534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tepperman BS, Fitzpatrick PJ. Second respiratory and upper digestive tract cancers after oral cancer. Lancet. 1981;2:547-549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chuang SC, Scelo G, Tonita JM, Tamaro S, Jonasson JG, Kliewer EV, Hemminki K, Weiderpass E, Pukkala E, Tracey E, Friis S, Pompe-Kirn V, Brewster DH, Martos C, Chia KS, Boffetta P, Brennan P, Hashibe M. Risk of second primary cancer among patients with head and neck cancers: A pooled analysis of 13 cancer registries. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:2390-2396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 230] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Gandini S, Botteri E, Iodice S, Boniol M, Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P, Boyle P. Tobacco smoking and cancer: A meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:155-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 540] [Cited by in RCA: 589] [Article Influence: 32.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Abbas G, Krasna M. Overview of esophageal cancer. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2017;6:131-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | de Hingh IH, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Laguna Pes MP, Busch OR, van Lanschot JJ. Synchronous esophageal and renal cell carcinoma: Incidence and possible treatment strategies. Dig Surg. 2008;25:27-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Díaz de Liaño A, Moras N, Ciga MA, Oteiza F, Ortiz H. Simultaneous presentation of oesophageal and renal cancer. Clin Transl Oncol. 2007;9:195-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Fékété F, Sauvanet A, Kaisserian G, Jauffret B, Zouari K, Berthoux L, Flejou JF. Associated primary esophageal and lung carcinoma: A study of 39 patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;58:837-842. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Gyorki DE, Clarke NE, Hii MW, Banting SW, Cade RJ. Management of synchronous tumours of the oesophagus and pancreatic head: A novel approach. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2011;93:e111-e113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ishii H, Sato H, Tsubosa Y, Kondo H. Treatment of double carcinoma of the esophagus and lung. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;56:126-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Isohata N, Naritaka Y, Shimakawa T, Asaka S, Katsube T, Konno S, Murayama M, Shiozawa S, Yoshimatsu K, Aiba M, Ide H, Ogawa K. Occult lung cancer incidentally found during surgery for esophageal and gastric cancer: A case report. Anticancer Res. 2008;28:1841-1847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Jayaprakash N, O'Kelly F, Lim KT, Reynolds JV. Management of synchronous adenocarcinoma of the esophago-gastric junction and ampulla of Vater: Case report of a surgically challenging condition. Patient Saf Surg. 2009;3:23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kato H, Tachimori Y, Watanabe H, Mizobuchi S, Igaki H, Yamaguchi H, Ochiai A. Esophageal carcinoma simultaneously associated with gastric carcinoma: Analysis of clinicopathologic features and treatments. J Surg Oncol. 1994;56:122-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kim JY, Hanasono MM, Fleming JB, Berry MD, Hofstetter WL. Combined esophagectomy and pancreaticoduodenectomy: Expanded indication for supercharged jejunal interposition. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:1893-1895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Kobayashi S, Kabuto T, Doki Y, Yamada T, Miyashiro I, Murata K, Hiratsuka M, Kameyama M, Ohigashi H, Sasaki Y, Ishikawa O, Imaoka S. Synchronous esophageal and renal cell carcinoma. Dis Esophagus. 2000;13:305-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kurosaki I, Hatakeyama K, Nihei K, Suzuki T, Tsukada K. Thoracic esophagectomy combined with pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy in a one-stage procedure: Report of a case. Surg Today. 2000;30:168-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Lindenmann J, Matzi V, Maier A, Smolle-Juettner FM. Transthoracic esophagectomy and lobectomy performed in a patient with synchronous lung cancer and combined esophageal cancer and esophageal leiomyosarcoma. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;31:322-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Mafune K, Tanaka Y, Ma YY, Takubo K. Synchronous cancers of the esophagus and the ampulla of Vater after distal gastrectomy: Successful removal of the esophagus, gastric remnant, duodenum, and pancreatic head. J Surg Oncol. 1995;60:277-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Motoori M, Tsujinaka T, Kobayashi K, Fujitani K, Kikkawa N. Synchronous rectal and esophageal cancer associated with prurigo chronica multiformis: Report of a case. Surg Today. 2001;31:1087-1090. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Nagahama T, Goseki N, Kato S, Maruyama M, Endo M. Esophageal carcinoma and coexisting hepatocellular carcinoma resected simultaneously. Arch Surg. 1996;131:208-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Vilcea ID, Vasile I, Tomescu P, Mirea C, Vilcea AM, Stoica L, Mesina C, Dumitrescu T, Cheie M, Enache MA. Synchronous squamous esophageal carcinoma and urothelial renal cancer. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2010;105:843-847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Akiyama Y, Iwaya T, Konosu M, Shioi Y, Endo F, Katagiri H, Nitta H, Kimura T, Otsuka K, Koeda K, Kashiwaba M, Mizuno M, Kimura Y, Sasaki A. Curative two-stage resection for synchronous triple cancers of the esophagus, colon, and liver: Report of a case. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;13:1-4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Chan CH, Cools-Lartigue J, Marcus VA, Feldman LS, Ferri LE. The impact of incidental gastrointestinal stromal tumours on patients undergoing resection of upper gastrointestinal neoplasms. Can J Surg. 2012;55:366-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Fukaya M, Abe T, Yokoyama Y, Itatsu K, Nagino M. Two-stage operation for synchronous triple primary cancer of the esophagus, stomach, and ampulla of Vater: Report of a case. Surg Today. 2014;44:967-971. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | I H, Kim GH, Park DY, Kim YD, Lee BE, Ryu DY, Kim DU, Song GA. Management of gastric epithelial neoplasia in patients requiring esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. Dis Esophagus. 2013;26:603-608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Wang XX, Liu TL, Wang P, Li J. Is surgical treatment of cancer of the gastric cardia or esophagus associated with a concurrent major pulmonary operation feasible? One center's experience. Chin Med J (Engl). 2012;125:193-196. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Xie S, Huang J, Kang G, Fan G, Wang W. Surgical treatment of synchronous gastric and esophageal carcinoma: Case report and review of literature. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Rep. 2013;2:35-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Zhou Y, Wu XD, Shi Q, Jia J. Coexistence of gastrointestinal stromal tumor, esophageal and gastric cardia carcinomas. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:2005-2008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Kanda T, Sato Y, Yajima K, Kosugi S, Matsuki A, Ishikawa T, Bamba T, Umezu H, Suzuki T, Hatakeyama K. Pedunculated gastric tube interposition in an esophageal cancer patient with prepyloric adenocarcinoma. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2011;3:75-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Suzuki S, Nishimaki T, Suzuki T, Kanda T, Nakagawa S, Hatakeyama K. Outcomes of simultaneous resection of synchronous esophageal and extraesophageal carcinomas. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;195:23-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Greene CL, DeMeester SR, Augustin F, Worrell SG, Oh DS, Hagen JA, DeMeester TR. Long-term quality of life and alimentary satisfaction after esophagectomy with colon interposition. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;98:1713-9; discussion 1719-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Irino T, Tsekrekos A, Coppola A, Scandavini CM, Shetye A, Lundell L, Rouvelas I. Long-term functional outcomes after replacement of the esophagus with gastric, colonic, or jejunal conduits: A systematic literature review. Dis Esophagus. 2017;30:1-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Mine S, Udagawa H, Tsutsumi K, Kinoshita Y, Ueno M, Ehara K, Haruta S. Colon interposition after esophagectomy with extended lymphadenectomy for esophageal cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:1647-1653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Saito S, Nakamura M, Hosoya Y, Kitayama J, Lefor AK, Sata N. Postoperative quality of life and dysfunction in patients after combined total gastrectomy and esophagectomy. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2017;22:34-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |