Published online Oct 7, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i37.8283

Peer-review started: May 1, 2016

First decision: June 20, 2016

Revised: July 28, 2016

Accepted: August 10, 2016

Article in press: August 10, 2016

Published online: October 7, 2016

Processing time: 154 Days and 22.2 Hours

The last decade has witnessed remarkable technological advances in mass spectrometry-based proteomics. The development of proteomics techniques has enabled the reliable analysis of complex proteomes, leading to the identification and quantification of thousands of proteins in gastric cancer cells, tissues, and sera. This quantitative information has been used to profile the anomalies in gastric cancer and provide insights into the pathogenic mechanism of the disease. In this review, we mainly focus on the advances in mass spectrometry and quantitative proteomics that were achieved in the last five years and how these up-and-coming technologies are employed to track biochemical changes in gastric cancer cells. We conclude by presenting a perspective on quantitative proteomics and its future applications in the clinic and translational gastric cancer research.

Core tip: Protein identification and quantification by mass spectrometry represent powerful techniques for deciphering the mechanisms underlying the biochemical anomalies that cause human diseases. Due to innovations in mass spectrometry and labeling techniques, cellular protein levels can be monitored routinely with great accuracy. This review provides a brief overview of these technological advances and their applications in gastric cancer biology.

- Citation: Kang C, Lee Y, Lee JE. Recent advances in mass spectrometry-based proteomics of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(37): 8283-8293

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i37/8283.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i37.8283

Functional interpretations of the genes that are associated or linked with cancer by various genomics approaches often require other orthogonal approaches that could provide information beyond the data obtained from sequence analysis of those genes. Since Wilkins and Williams[1] first proposed the concept of the proteome in 1994, the field of proteomics has recently experienced a dramatic development that has largely been driven by technological advances in the field of mass spectrometry.

The introduction of advanced mass spectrometric instruments and bioinformatics tools has enabled the high-resolution and high-specificity analyses of thousands of proteins and their post-translational modification states in cultured cells, primary tissues, and body fluids[2]. Despite the inherent low sensitivity and undersampling suffered by mass spectrometry[3,4], researchers have started to design strategies that capitalize on this emerging technology for the elucidation of disease pathobiology[5-7].

Gastric cancer is one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths worldwide[8,9]. With approximately one million cases diagnosed each year, gastric cancer is also one of the most common cancers, particularly in East Asia[8]. Despite a modest decline in newly diagnosed cases worldwide, the mortality rate of gastric cancer remains higher than other malignancies, mainly due to the lack of noninvasive handy diagnostics of early gastric cancer[8]. Moreover, the pathogenic mechanism underlying gastric tumorigenesis is still unknown, and the only curative treatment for gastric cancer remains surgery.

Aimed at obtaining a full understanding of the molecular determinants that drive gastric cancer, many studies have increasingly adopted advanced proteomic technologies that can help identify protein biomarkers and elucidate the molecular mechanisms of gastric cancer. This review discusses the technological breakthroughs in mass spectrometry-based quantitative proteomics and their applications in gastric cancer research.

Table 1 summarizes the mass spectrometric technologies that have been adopted to study gastric cancer. Mass spectrometric measurements detect and identify the chemical composition of ionized analytes based on the mass-to-charge ratio, m/z. A typical mass spectrometer is composed of an ion source that ionizes the analytes, mass analyzer(s) for the detection of m/z, and detector(s) for counting the intensities of the ions[10]. Ionization is commonly achieved by soft ionization techniques, such as matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI)[11] and electrospray ionization (ESI)[12], to measure the masses of proteins and peptides. In MALDI, the analytes are ionized with a crystalline matrix via laser pulses, whereas in ESI, the analytes are directly ionized from a solution that is typically eluted from liquid chromatography (LC) columns. MALDI is usually adopted to analyze simple samples, whereas LC-ESI is used to analyze complex mixtures.

| Sample | Measurand | Mass spectrometry | Identification/quantification | Ref. |

| Tissue samples | ||||

| GC tissue | Global proteome | MALDI TOF/TOF, LTQ Orbitrap XL | Label-free, Mascot | Balluff et al[16], 2011 |

| GC tissue | Global proteome | Q-TOF | O18/O16, MassLynx (v4.0) | Zhang et al[73], 2013 |

| GC tissue | Global proteome | LTQ Orbitrap | Label-free, ProLuCID (v1.3) | Aquino et al[74], 2014 |

| GC tissue | Global proteome | MALDI TOF/TOF | Label-free, Mascot (v2.2) | Wu et al[75], 2014 |

| GC tissue | Global proteome | LTQ Orbitrap XL | Label-free, Mascot (v2.2) | Ichikawa et al[38], 2015 |

| GC tissue | Global proteome | LTQ Orbitrap XL | Label-free, Bioworks Browser (v3.3.1), Trans-Proteomic Pipeline (v4.0) | Shen et al[76], 2015 |

| GC tissue | Membrane proteome | LTQ Orbitrap Velos | TMT, MaxQuant (v1.2.2.5) | Gao et al[31], 2015 |

| Gastroesophageal malignancy | Global proteome | MALDI TOF/TOF | iTRAQ, Mascot | Singhal et al[14], 2013 |

| Serum samples | ||||

| Sera from GC patients | Serum proteome | MALDI-TOF LTQ Orbitrap XL MS/MS | Label-free, Autoflex, Peptide mass fingerprinting | Fan et al[37], 2013 |

| Sera from GC patients | Serum proteome | Triple TOF 5600 | Multiple reaction monitoring | Humphries et al[59], 2014 |

| Sera from GC patients | Serum proteome | MALDI-TOF Orbitrap Q-Exactive | Label-free, MaxQuant (v1.4.1.1) | Abramowicz et al[50], 2015 |

| Sera from GC patients | Serum proteome | LTQ Orbitrap Velos | iTRAQ, SEQUSET HT, Mascot (v2.2) | Subbannayya et al[29], 2015 |

| Sera from GC patients | Serum proteome | SELDI TOF MS MALDI TOF/TOF | Label-free, Mascot | Song et al[17], 2016 |

| Cell lines | ||||

| BGC823, MKN45, SCG7901 | Global proteome | MALDI TOF/TOF | Label-free, Mascot | Cai et al[71], 2013 |

| AGS, AZ521, FU97, MKN7, MKN74, NCI-N87, SNU16, YCC1, YCC2, YCC3, YCC9 | Global proteome | MALDI TOF/TOF | iTRAQ, ProteinPilot | Hou et al[69], 2013 |

| AGS | Global proteome | Q-TOF | iTRAQ, Mascot (v2.1.1) | Hu et al[72], 2013 |

| MKN45 | Global proteome | MALDI TOF/TOF | Label-free, Mascot | Hu et al[13], 2013 |

| OCUM-2MD3, OCUM-12 | Global proteome | Q-TOF | iTRAQ, ProteinPilot | Morisaki et al[28], 2014 |

| AGS, BGC823, MKN45, SGC7901 | Global proteome | MALDI TOF/TOF | Label-free, Peptide mass fingerprinting | Yang et al[67], 2014 |

| HGC27, MGC803, SGC7901 | Global proteome | LTQ Orbitrap | Label-free, Mascot (v2.3.2), Scaffold (v4.0.5), X! Tandem CYCLONE (v2010.12.01.1) | Qiao et al[62], 2015 |

| AGS | Global proteome | Q-TOF | iTRAQ, Mascot (v2.3.2) | Lin et al[61], 2015 |

| HGC27 | Global proteome | Triple TOF 5600 | iTRAQ, Mascot (v2.3.2) | Chen et al[77], 2016 |

| AGS, MKN7 | Secretome | MALDI TOF/TOF | iTRAQ, ProteinPilot | Loei et al[51], 2011 |

| AGS, KATO III, NCI-N87, SNU1, SNU5, SNU16 | Secretome | LTQ Orbitrap Velos | SILAC, Proteome Discoverer (v1.3.0.339), Mascot, SEQUEST | Marimuthu et al[33], 2013 |

| AGS, KATO III, SNU1, SNU5, MKN7, IM95 | Membrane proteome | LTQ-FT Ultra | Label-free, Trans-Proteomic Pipeline, Mascot (v2.2.07) | Guo et al[68], 2012 |

| AGS, IM95, KATO3, MKN7, MKN28, MKN45, NUGC3, NUGC4, SCH, SNU1, SNU5, SNU16 | Membrane proteome | Q-TOF | iTRAQ, ProteinPilot | Yang et al[70], 2012 |

| AGS, HGC27, KATO III, MKN45, NUGC3, SCH, SGC7901, SNU5, SNU484, TSK1 | Membrane proteome | Q-TOF | iTRAQ, ProteinPilot | Goh et al[60], 2015 |

| Multidrug-resistant GC cell lines: GC7901/VCR, SGC7902/ADR | Surface glycoproteome | LTQ Orbitrap XL | Triplex stable isotope dimethyl labeling, Mascot, MSQuant (v2.0a81) | Li et al[47], 2013 |

| AGS | Interactome | LTQ Orbitrap Velos | Label-free, Mascot (v2.2.2) | Yu et al[57], 2013 |

| AGS | Phosphoproteome | MALDI TOF/TOF | SILAC, Mascot (v2.1) | Holland et al[43], 2011 |

| AGS | Phosphoproteome | LTQ Orbitrap XL | SILAC, MaxQuant (v1.3.0.5) | Glowinski et al[42], 2014 |

Two major types of mass analyzers are used in current proteomics technology. In time-of-flight (TOF) mass spectrometers, the flight times of ions are measured over a fixed distance to match a specific m/z, and the intensity of a measurement is correlated with the amount of the ion. MALDI ionization coupled with TOF technology allows the MALDI-TOF mass analyzer to analyze proteins and peptides with a wide range of molecular weights[10]. Due to its simplicity, excellent mass accuracy, high resolution, and great sensitivity, MALDI-TOF has been widely adopted to identify proteins associated with diseases, including gastric cancer.

Using MALDI-TOF, Hu et al[13] have shown that overproduction of the C-X-C chemokine receptor type 1 (CXCR1) was linked with late-stage gastric cancer. The authors compared the protein abundance profiles of the MKN45 gastric cancer cell line in the presence and absence of CXCR1 overexpression and found that the cellular levels of 29 proteins differed. As these proteins were known to participate in cell adhesion, cellular metabolism, and the cell cycle, CXCR1 was inferred to play a role in the proliferation, metastasis, and invasion of gastric cancer.

In an attempt to understand the inhibitory function of curcumin, curcumin-treated samples were analyzed with MALDI-TOF, and 75 proteins displayed significant changes in abundance. In this study, Singhal et al[14] identified putative biomarkers of gastrointestinal tract cancers by analyzing biopsy samples obtained from patients with gastroesophageal malignancies using MALDI-TOF.

Recently, the application of MALDI has been expanded to obtaining mass images of tissues[15]. In MALDI imaging mass spectrometry, the masses of biomolecules are probed two-dimensionally in a thin tissue section, providing valuable spatial information about the analytes that is lost in typical LC-mass spectrometry experiments. Balluff et al[16] have utilized MALDI imaging mass spectrometry to identify prognostic biomarkers that can be used to predict disease outcomes after surgical resection. The prognostic value of the three identified proteins (CRIP1, HNP-1, and S100-A6) was validated immunohistochemically with tissue microarrays using an independent validation cohort.

Surface-enhanced laser desorption/ionization (SELDI) is a variation of MALDI, in which the analytes are bound to a surface before the mass analysis. The surface can be modified to allow for specific binding of the analytes of interest. Like MALDI, SELDI is usually coupled with TOF for protein identification. Using SELDI-TOF, Song et al[17] identified 15 proteins that were differentially regulated in the serum samples from 296 gastric cancer patients.

The second type of mass analyzer is the ion trap, in which the ionized analytes are first trapped and then subjected to mass spectrometry. The ion trap is less expensive than the MALDI-TOF analyzer but is still sensitive enough to measure non-abundant analytes. Therefore, until recently, ion traps have been commonly used to obtain a majority of proteomics data, despite their relatively low mass accuracy[10].

The Fourier transform (FT) mass spectrometer is an advanced ion trap mass analyzer that exploits strong magnetic field to measure the m/z of ions. FT mass spectrometry boasts sensitivity, accuracy, resolution, and dynamic range[18]. These advantages make FT mass spectrometry suitable for analyzing proteins in a complex mixture. However, its application in proteomics has largely been hindered by its cost and difficulties in operation and maintenance.

The Orbitrap analyzer, a variant of the FT mass spectrometer, made its debut in 2005. Like the FT mass spectrometer, the Orbitrap mass analyzer converts the image currents produced in a trap to mass spectra by Fourier transform[19]. Orbitrap uses electrostatic forces rather than a magnetic field and, thus, does not require the expensive superconducting magnets used in FT mass spectrometers. Orbitrap is currently widely used in proteomics research and is chosen for complex proteome analysis.

“Shotgun proteomics” resulted from the coupling of high-performance liquid chromatography with ESI technology[20]. In this approach, the proteome subject to mass analysis is first digested with a specific protease(s), such as trypsin. The resulting digest composed of proteolytic peptides from the entire proteins in the sample is separated by liquid chromatography before the first mass analysis of the intact peptides (MS1). Additional information about the parent peptide ions is obtained by fragmenting the parent peptides with non-proteolytic methods and measuring the m/z of product ions in the second mass analysis (MS2)[21].

This non-proteolytic fragmentation step is a key to peptide identification, as the amino acid sequence information is inferred from the mass spectra of the fragmented peptides[21]. The most common method used to generate fragment ion spectra of the selected precursor ions is collision-induced dissociation (CID)[22]. Electron transfer dissociation (ETD), an alternative fragmentation technique, has some advantages over CID in accurately assessing post-translational modifications such as glycosylation and phosphorylation, because ETD tends to preserve these modifications when the modified peptide is fragmented[23].

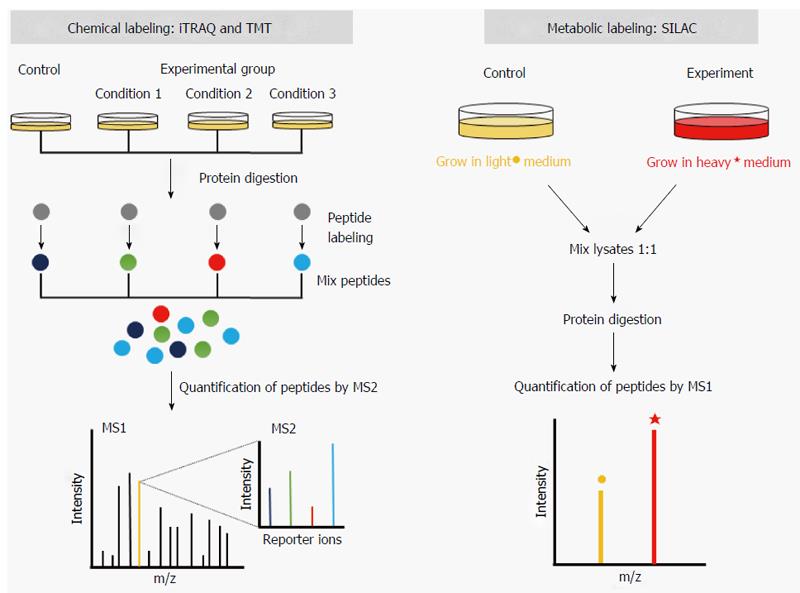

Instead of providing mere lists of proteins, quantitative proteomics can deliver information about the differences in proteomes between two samples, and this information may be more useful for studying biological and biochemical processes. The development of quantitative proteomics owes much to the unique labeling strategies that enables a mass spectrometer to distinguish the same proteins or peptides from different samples. These labeling strategies are designed such that labeling causes a known mass shift in the labeled protein or peptide in the mass spectrum.

In general, differentially labeled samples are mixed and analyzed in the same mass spectrometric run, where the differences in the peak intensities of the labeled peptide pairs are assumed to reflect the differences in the abundance of the corresponding proteins. For instance, it is possible to compare the proteomes from normal and cancerous tissues using this approach. Quantitative mass spectrometry-based proteomics approaches include stable isotope labeling techniques and label-free strategies.

Stable isotope labeling entails the incorporation of stable heavy atoms such as 13C and 15N into specific biomolecular entities, as previously reviewed[24]. In most cases, these labels are chemically or metabolically introduced into peptides or proteins. One of the first chemical labeling strategies adopted for protein quantification by mass spectrometry was the isotope-coded affinity tag (ICAT) technique[25]. In this approach, the sulfhydryl groups in cysteine residues are covalently modified by the ICAT reagents containing “light” or “heavy” isotopes. The presence of the light or heavy ICAT tags leads to the separation and concomitant quantification of modified peptides during the precursor ion measurements in the first mass spectrometry process (MS1).

Recently, chemical labeling strategies utilizing isobaric tags, i.e., tags with the same molecular weight, developed for relative and absolute quantification (iTRAQ)[26] and tandem mass tags (TMT)[27] have gained popularity in proteomics. iTRAQ and TMT reagents differ from ICAT reagents in that the ε-amino group of lysine and α-amino group of the N-terminal residue in peptides are modified. The labeled peptides are quantified during the second mass spectrometry process (MS2) when the tags are released upon fragmentation of the peptides (Figure 1). Advantages of the isobaric tags include a multiplexing capacity of up to eight separate samples in a single mass spectrometric run. Additionally, because isobaric tags modify amino groups, which are more abundant than sulfhydryl groups in most proteins, the coverage of quantification by iTRAQ and TMT is also greater than by ICAT.

A large number of studies quantifying the proteomes of gastric cancer using the iTRAQ approach have been reported. Morisaki et al[28] applied iTRAQ to identify potential biomarkers in gastric cancer stem cells and identified nine proteins that were overproduced in gastric cancer stem cells. Using iTRAQ, Subbannayya et al[29] defined a set of potential biomarkers in sera from gastric cancer patients. In their study, more than 50 proteins were found to exhibit altered levels in samples from gastric cancer patients.

TMT has also been used to quantify gastric cancer proteomes. Gao et al[30] found that 234 mitochondrial protein genes were differentially expressed in gastric cancer using TMT. In another study employing TMT, Gao et al[31] revealed that 82 plasma membrane proteins were dysregulated in gastric cancer.

An alternative to stable isotope labeling technique is metabolic labeling. This approach takes advantage of the metabolic incorporation of heavy isotopes in live cells under culture conditions. Quantification by metabolic labeling is less error-prone than chemical labeling because the labels are introduced before the samples are prepared. Stable isotope labeling with amino acids in cell culture (SILAC)[32] is one of the most popular metabolic labeling techniques (Figure 1). Developed by Ong et al[32], SILAC labels proteins in the cells by growing them in the medium containing heavy amino acids. The most common heavy amino acids used in SILAC are lysine-4, lysine-8, arginine-6, and arginine-10. Different combinations of heavy lysines and arginines can be used such that up to three simultaneous quantifications are possible as follows: a light sample (Lys-0 and Arg-0), medium sample (Lys-4 and Arg-6), and heavy sample (Lys-8 and Arg-10).

As trypsin is the most popular protease used for the preparation of peptide mixtures, which cleaves the carboxyl side of lysine or arginine, the use of heavy lysine and arginine in SILAC helps increase the coverage of quantification by ensuring that every peptide analyzed by the mass spectrometer contains at least one heavy amino acid. Like labeling with ICAT, the quantification of proteins labeled with the SILAC approach is carried out by comparing the intensities of precursor peptide ions in the MS1 process. Quantification employing the SILAC method has been applied in gastric cancer proteomics. Marimuthu et al[33] studied the secretomes from neoplastic and non-neoplastic gastric epithelial cells using SILAC. The authors identified 263 proteins that were upregulated in gastric cancer-derived cells compared to non-neoplastic gastric epithelial cells.

Another quantification strategy used in proteomics, the label-free approach, inherently suffers from low reproducibility caused by experimental errors and requires precise optimization of mass spectrometric instrumentations[34]. Nevertheless, label-free quantification can overcome some of the limitations of stable isotope labeling strategies. For example, the time-consuming and costly labeling steps can be eliminated, and the sample numbers are not limited by the multiplexing capacity (three for SILAC and eight for iTRAQ or TMT).

Two types of label-free quantification approaches are routinely used. In spectral counting, the relative abundance of a specific protein among the samples is evaluated by the number of tandem mass (MS2) spectra that can be matched to the protein[35]. Employing this approach, Uen et al[36] identified biomarker candidates in plasma samples obtained from gastric cancer patients. The authors found 17 proteins with differential expression patterns in gastric cancer.

The second label-free quantitative method requires high-resolution mass spectrometers and quantifies the intensities of the precursor peptide ion, in which the number of possible tryptic peptides from a given protein are often used for normalization[24]. Using this method, Fan et al[37] defined novel diagnostic biomarkers for gastric cancer. The authors analyzed serum samples from gastric cancer patients and discovered four deregulated proteins that were differentially expressed in the patients’ sera. Another recent label-free quantitative proteomics by Ichikawa et al[38] showed the prognostic importance of a tumor suppressor PML (promyelocytic leukemia) in treating gastrointestinal stromal tumors.

In addition to quantifying the global proteome, the analysis and quantitative assessment of post-translational modifications (PTMs) of a proteome is a powerful approach to understanding the signal flux in disease samples, including gastric cancer cell lines and tissues. Mann et al[39] have previously reviewed PTM analysis by mass spectrometry. Of the many PTMs, phosphorylation and glycosylation associated with gastric cancer have been studied using quantitative proteomic methodologies. When only a minute fraction of protein is modified at any given time point, the detection and quantification of PTM by mass spectrometry are significant challenges.

Due to these technological limitations, mass spectrometric PTM analysis requires additional sample preparation steps that enrich the modified peptides. For instance, phosphoproteome analyses rely on the enrichment of phosphorylated peptides using an anti-phosphopeptide antibody, immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC), or titanium-dioxide beads[40,41]. Using an immobilized phosphotyrosine-specific antibody, Glowinski et al[42] reported 85 different proteins that exhibited altered phosphorylation upon infection with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), an organism strongly linked with gastric cancer. Holland et al[43] also found that the phosphorylation of 20 proteins was differentially regulated by H. pylori infection using IMAC enrichment approach.

Additionally, protein glycosylation has been mapped in gastric cancer cells. Asparagine, serine, and threonine residues of proteins are glycosylated in the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus. Increased glycosylation has been associated with the proliferation and progression of various cancers, and glycans with specific structures have been associated with tumor malignancy[44-46]. Li et al[47] performed quantitative proteomic analysis to identify and quantify eleven cell surface N-glycoproteins with differential expression patterns in multidrug-resistant (MDR) gastric cancer and to define the cell surface glycoproteome that is related to resistance to multiple drugs, including vincristine (also known as leurocristine) or doxorubicin (e.g., Adriamycin), which are used to treat gastric cancer.

A systematic assessment of the secretome, i.e., all secretory proteins from a cell, may provide crucial insights into cancer biology, as the composition of proteins that are secreted from cancer tissues differs from the proteins that are secreted from normal tissues[48]. The secretome and serum proteome, i.e., all proteins in the blood serum, are considered a major source of cancer biomarkers, and some important regulatory proteins that are secreted into the serum have been used as tumor biomarkers[49].

In a study seeking to characterize the serum proteome from local and invasive gastric cancer, Abramowicz et al[50] analyzed serum samples acquired from patients with locally advanced or metastatic cancers and healthy controls. Several proteins with different abundances were detected in cancer patients, with no evidence of differences between the patients with local and invasive cancers. Loei et al[51] have compared the secretomes of AGS and MKN7 cells using iTRAQ labeling and found that 43 protein genes were differentially expressed between the two cell lines. Among these proteins, granulin was confirmed by immunohistochemistry to be frequently found in gastric tumor tissues, but it was not found in the normal gastric epithelia.

As tumor has been defined as a disease of pathways[52], interactome analysis may offer some valuable insights into cancer biology by offering information beyond the changes in the abundance of individual proteins[53]. In practice, characterizing alterations in protein-protein interactions in cancer is becoming more relevant, as many studies have reported that patients affected by the same type of cancer display diverse protein expression patterns and activation of oncogenic kinases[54-56]. In these cases, classifications based on protein-protein interaction subnetworks offered greater accuracy than classifications based on individual marker genes[55].

For this reason, interactome analysis represents an attractive avenue for understanding gastric cancer biology, although its broad applications remain to be established. The first interactome analysis of gastric cancer was performed with valosin-containing protein (VCP), a protein associated with H. pylori-induced gastric cancer[57]. In seeking the interacting partner proteins for VCP, Yu et al[57] immunoprecipitated VCP and then performed a quantitative mass spectrometric analysis. The authors identified 288 putative binding partners of VCP in the AGS gastric cancer cell line, providing unexpected new insights into the function of H. pylori in gastric cancer.

In targeted proteomics, prior knowledge of analytes is necessary, which is an attribute not essential for the aforementioned discovery-based proteomics. In this regard, targeted proteomics is similar to immunoassays, in which antibodies recognize and identify specific proteins. Targeted proteomics is emerging as an alternative approach to discovery proteomics or immunoassays, particularly when pre-defined analytes are present at low levels and no reliable antibodies are available.

Selected reaction monitoring (SRM) is the most common approach used for targeted proteome measurements and requires a triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer, as previously reviewed by Picotti et al[58] In SRM, a peptide precursor ion from a specific protein with a particular m/z is selected in the first phase of tandem mass spectrometry, and a signature product ion is produced by fragmenting the precursor ion and detected by the second phase of mass spectrometry.

The sensitivity and reproducibility of SRM are greater than conventional discovery-based mass spectrometry because only a set of predefined proteins is programmed to be analyzed by the SRM mass spectrometer. Another advantage of SRM lies in its speed. After SRM assays have been defined, they are significantly faster than a typical discovery-based mass spectrometry. In addition, the measurements can be multiplexed such that one can measure hundreds or even thousands of peptides in a single mass spectrometric run. The SRM approach has been successfully exploited to test the specificity of afamin, clusterin, haptoglobin, and vitamin D-binding protein as potential serum biomarkers of gastric cancer[59].

Several gastric cancer cell lines have been subjected to recent mass spectrometric analyses as a model mimicking gastric cancer. These studies are summarized in Table 2. In a recent study aimed at defining the proteomes of gastric cancer, Goh et al[60] have quantified the membrane proteomes of eleven gastric cancer cell lines, including AGS, HGC-27, MKN45, and SGC-7901 cells. A total of 882 proteins were detected, and 57 proteins were upregulated, with a greater than 1.3-fold change in at least six of the eleven cell lines. Depletion of DLAT, a subunit of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex that was upregulated, reduced cell proliferation. This study contributed to the recent interest and discussion in cancer energetics and related phenomena, such as the Warburg and reverse Warburg effects.

| Cell line | Ref. | Aim of study | Proteins analyzed | Validation1 |

| AGS | Holland et al[43], 2011 | Phosphoproteome upon H. pylori infection | 20 altered in abundance by H. pylori | No |

| Loei et al[51], 2011 | Secretome of AGS and MKN7 | 43 differed | IHC/WB | |

| Guo et al[68], 2012 | Plasma membrane proteome | 1473 identified | IHC | |

| Hou et al[69], 2013 | Biomarkers for GC metastasis | 19 increased and 34 decreased in metastasis | IHC/WB | |

| Hu et al[72], 2013 | Global profile of miR-148a-regulated proteins | 55 altered by miR-148a | WB | |

| Marimuthu et al[33], 2013 | Secretome | 263 increased and 45 decreased in GC | IHC | |

| Yu et al[57], 2013 | Interactome of VCP | 288 putative partners, including 18 PI3K/Akt proteins | WB | |

| Glowinski et al[42], 2014 | Tyrosine signaling upon H. pylori transfection | 85 altered by H. pylori | No | |

| Goh et al[60], 2015 | Membrane proteome of 11 GC cell lines | 882 altered, including 57 increased in ≥ 6 cell lines | WB | |

| Lin et al[61], 2015 | Tanshinone IIA regulation | 102 altered by tanshinone IIA treatment | WB | |

| BGC-823 | Cai et al[71], 2013 | Effects of curcumin on viability and apoptosis | 75 altered by curcumin treatment | No |

| HGC-27 | Goh et al[60], 2015 | Membrane proteome of 11 GC cell lines | 882 altered, including 57 increased in ≥ 6 cell lines | WB |

| Qiao et al[62], 2015 | Proteomes of three GC cell lines | 9 altered | IHC/WB | |

| Chen et al[77], 2016 | Proteome with FAF1 or H. pylori | 157 altered by FAF1, 500 by H. pylori and 246 by both | WB | |

| MGC-803 | Qiao et al[62], 2015 | Proteomes of three GC cell lines | 9 altered | IHC/WB |

| MKN7 | Loei et al[51], 2011 | Secretome of AGS and MKN7 | 43 differed | IHC/WB |

| Guo et al[68], 2012 | Plasma membrane proteome | 1473 identified | IHC | |

| Yang et al[70], 2012 | Membrane proteome | 175 altered | IHC/WB | |

| MKN45 | Hu et al[13], 2013 | Proteome changes following CXCR1 knockdown | 16 increased and 13 decreased by CXCR1 knockdown | WB |

| Yang et al[67], 2014 | Proteome changes following NAIF1 overexpression | 5 increased and 3 decreased by NAIF1 overexpression | WB | |

| Goh et al[60], 2015 | Membrane proteome of 11 GC cell lines | 882 altered, including 57 increased in ≥ 6 cell lines | WB | |

| SGC-7901 | Li et al[47], 2013 | Cell surface glycoproteome of MDR | 11 altered in MDR cell lines | WB |

| Goh et al[60], 2015 | Membrane proteome of 11 GC cell lines | 882 altered, including 57 increased in ≥ 6 cell lines | WB | |

| Qiao et al[62], 2015 | Proteomes of three GC cell lines | 9 altered | IHC/WB |

In another proteomic analysis of AGS cells, the most intensively studied cell line in gastric cancer proteomics, Lin et al[61] sought to elucidate the mechanism of tanshinone IIA (TIIA) regulation. TIIA is a plant extract used in traditional Chinese herbal medicine that has been reported to have anti-tumor potential against gastric cancer. The authors reported that the cellular levels of the 102 unique proteins were altered upon TIIA treatment.

Other gastric cancer cell lines have also been adopted for proteomic analysis. Qiao et al[62] have quantified the proteomes from SGC-7901, HGC-27, and MGC-803 cells. The authors have found that filamin c and a large actin-cross-linking protein were significantly downregulated, establishing functional roles for these proteins in gastric cancer.

Quantitative proteomic analyses can provide information on proteins that are differentially abundant in cancerous tissues. These proteins, if verified, may serve as biomarkers for the diagnosis and prognosis of cancer and could be extremely useful for clinical purposes. A mass spectrometry-based cancer biomarker study typically starts with the aforementioned discovery-based proteomics by assessing the differences in the proteome profiles in small cohorts or model systems.

Once candidate biomarkers are identified, orthogonal methodologies, such as antibody-based assays, are applied for biomarker validation and verification[63]. An increasing number of studies have adopted mass spectrometry to identify gastric cancer biomarkers recently and are reviewed in detail by Tsai et al[64], Liu et al[65], and Lin et al[66] We briefly discuss some cases in which the quantitative proteomic approaches described in this review are applied.

In an effort to identify membrane-originated biomarkers of gastric cancer, Yang et al[67] compared the relative abundances of membrane proteins from gastric cancer and control samples using the iTRAQ technique. Upregulation of the plasma membrane protein SLC3A2 in gastric cancer cells was validated by immunoblotting of a panel of thirteen gastric cancer cell lines and immunohistochemistry on tissue microarrays comprising 85 matched pairs of normal and tumor tissues.

Plasma membrane proteomes, including cluster of differentiation proteins and receptor tyrosine kinases, have been the subject of another biomarker search. A proteomic investigation by Guo et al[68] showed that four proteins, MET proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase (MET), ephrin type A receptor 2 (EPHA2), fibroblast growth factor receptor 2 (FGFR2), and integrin beta 4 (ITGB4), were upregulated in tumor tissues from 90% gastric cancer patients. Furthermore, three of them, MET, EPHA2, and FGFR2, were upregulated in all intestinal-type gastric cancers from this cohort.

In another attempt to identify potential biomarkers of gastric cancer, Marimuthu et al[33] quantified the secretome of gastric cancer by SILAC. The authors were able to identify and validate several gastric cancer biomarkers, including proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9, lectin mannose binding protein 2, and PDGFA-associated protein 1.

Biomarker candidates for gastric cancer metastasis have also been identified by quantitative proteomics. Hou et al[69] compared metastatic and non-metastatic gastric cancer cell lines with iTRAQ methods. The authors discovered that caldesmon was downregulated in metastasis-derived cell lines, which was confirmed by a further analysis of seven gastric cancer cell lines. In this study, knockdown of caldesmon in gastric cancer cells lead to an increase in cell migration and invasion, whereas upregulation of caldesmon resulted in a decrease in the phenotype.

Due to the progress made in mass spectrometry and quantitative proteomics over the past decade, it is now possible to probe thousands of proteins in a complex proteome. These technological advances include streamlined sample preparation, novel labeling strategies, and improved instrumentation, all of which contribute to the identification of gastric cancer-specific biomarkers, with increasing sensitivity and accuracy. Armed with these advanced proteomics technologies, research endeavors are seeking precise assessments of protein abundance, PTM, and protein-protein interactions that could help define the molecular signatures of gastric cancer susceptibility.

One remaining question is how these state-of-art technologies can be used in clinics and can make a bigger impact on the real-world management of gastric cancer. In this regard, one could envision the entrance of targeted proteomics into the realm of personalized diagnostics and medicine. Targeted proteomics can provide sensitivity and reproducibility, the core requirements for the technology to be applied to these new and exciting fields. In this scenario, once the key molecular determinants of gastric cancer are defined with time-consuming, discovery-based proteomics, targeted proteomics approaches, such as SRM, could be utilized for the rapid and reproducible monitoring of these key molecules and their networks for individual diagnostics or analyses of treatment responses.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Chen L, Codrici E, Garcia-Olmo D, Kon OL, Wang LF S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Wasinger VC, Cordwell SJ, Cerpa-Poljak A, Yan JX, Gooley AA, Wilkins MR, Duncan MW, Harris R, Williams KL, Humphery-Smith I. Progress with gene-product mapping of the Mollicutes: Mycoplasma genitalium. Electrophoresis. 1995;16:1090-1094. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Baker ES, Liu T, Petyuk VA, Burnum-Johnson KE, Ibrahim YM, Anderson GA, Smith RD. Mass spectrometry for translational proteomics: progress and clinical implications. Genome Med. 2012;4:63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lubec G, Afjehi-Sadat L. Limitations and pitfalls in protein identification by mass spectrometry. Chem Rev. 2007;107:3568-3584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Angel TE, Aryal UK, Hengel SM, Baker ES, Kelly RT, Robinson EW, Smith RD. Mass spectrometry-based proteomics: existing capabilities and future directions. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:3912-3928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 276] [Cited by in RCA: 285] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mischak H. How to get proteomics to the clinic? Issues in clinical proteomics, exemplified by CE-MS. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2012;6:437-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hanash S. Disease proteomics. Nature. 2003;422:226-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 751] [Cited by in RCA: 708] [Article Influence: 32.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Boja ES, Rodriguez H. The path to clinical proteomics research: integration of proteomics, genomics, clinical laboratory and regulatory science. Korean J Lab Med. 2011;31:61-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23762] [Cited by in RCA: 25545] [Article Influence: 1824.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 9. | Brenner H, Rothenbacher D, Arndt V. Epidemiology of stomach cancer. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;472:467-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 374] [Cited by in RCA: 411] [Article Influence: 25.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Aebersold R, Mann M. Mass spectrometry-based proteomics. Nature. 2003;422:198-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5042] [Cited by in RCA: 4586] [Article Influence: 208.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hillenkamp F, Karas M, Beavis RC, Chait BT. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry of biopolymers. Anal Chem. 1991;63:1193A-1203A. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Fenn JB, Mann M, Meng CK, Wong SF, Whitehouse CM. Electrospray ionization for mass spectrometry of large biomolecules. Science. 1989;246:64-71. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Hu W, Wang J, Luo G, Luo B, Wu C, Wang W, Xiao Y, Li J. Proteomics-based analysis of differentially expressed proteins in the CXCR1-knockdown gastric carcinoma MKN45 cell line and its parental cell. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai). 2013;45:857-866. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Singhal R, Carrigan JB, Wei W, Taniere P, Hejmadi RK, Forde C, Ludwig C, Bunch J, Griffiths RL, Johnson PJ. MALDI profiles of proteins and lipids for the rapid characterisation of upper GI-tract cancers. J Proteomics. 2013;80:207-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | McDonnell LA, Heeren RM. Imaging mass spectrometry. Mass Spectrom Rev. 2007;26:606-643. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Balluff B, Rauser S, Meding S, Elsner M, Schöne C, Feuchtinger A, Schuhmacher C, Novotny A, Jütting U, Maccarrone G. MALDI imaging identifies prognostic seven-protein signature of novel tissue markers in intestinal-type gastric cancer. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:2720-2729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Song D, Yue L, Li H, Zhang J, Yan Z, Fan Y, Yang H, Liu Q, Zhang D, Xia Z. Diagnostic and prognostic role of serum protein peak at 6449 m/z in gastric adenocarcinoma based on mass spectrometry. Br J Cancer. 2016;114:929-938. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Marshall AG, Hendrickson CL, Jackson GS. Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry: a primer. Mass Spectrom Rev. 1998;17:1-35. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 19. | Makarov A. Electrostatic axially harmonic orbital trapping: a high-performance technique of mass analysis. Anal Chem. 2000;72:1156-1162. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Tsiatsiani L, Heck AJ. Proteomics beyond trypsin. FEBS J. 2015;282:2612-2626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 23.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hunt DF, Yates JR, Shabanowitz J, Winston S, Hauer CR. Protein sequencing by tandem mass spectrometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:6233-6237. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Wells JM, McLuckey SA. Collision-induced dissociation (CID) of peptides and proteins. Methods Enzymol. 2005;402:148-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 302] [Cited by in RCA: 282] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Syka JE, Coon JJ, Schroeder MJ, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF. Peptide and protein sequence analysis by electron transfer dissociation mass spectrometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:9528-9533. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1907] [Cited by in RCA: 1790] [Article Influence: 85.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Bantscheff M, Lemeer S, Savitski MM, Kuster B. Quantitative mass spectrometry in proteomics: critical review update from 2007 to the present. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2012;404:939-965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 583] [Cited by in RCA: 569] [Article Influence: 43.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Gygi SP, Rist B, Gerber SA, Turecek F, Gelb MH, Aebersold R. Quantitative analysis of complex protein mixtures using isotope-coded affinity tags. Nat Biotechnol. 1999;17:994-999. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3651] [Cited by in RCA: 3242] [Article Influence: 124.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ross PL, Huang YN, Marchese JN, Williamson B, Parker K, Hattan S, Khainovski N, Pillai S, Dey S, Daniels S. Multiplexed protein quantitation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae using amine-reactive isobaric tagging reagents. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2004;3:1154-1169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3400] [Cited by in RCA: 3300] [Article Influence: 157.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Thompson A, Schäfer J, Kuhn K, Kienle S, Schwarz J, Schmidt G, Neumann T, Johnstone R, Mohammed AK, Hamon C. Tandem mass tags: a novel quantification strategy for comparative analysis of complex protein mixtures by MS/MS. Anal Chem. 2003;75:1895-1904. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Morisaki T, Yashiro M, Kakehashi A, Inagaki A, Kinoshita H, Fukuoka T, Kasashima H, Masuda G, Sakurai K, Kubo N. Comparative proteomics analysis of gastric cancer stem cells. PLoS One. 2014;9:e110736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Subbannayya Y, Mir SA, Renuse S, Manda SS, Pinto SM, Puttamallesh VN, Solanki HS, Manju HC, Syed N, Sharma R. Identification of differentially expressed serum proteins in gastric adenocarcinoma. J Proteomics. 2015;127:80-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Gao W, Xua J, Wang F, Zhang L, Peng R, Zhu Y, Tang Q, Wu J. Mitochondrial Proteomics Approach Reveals Voltage-Dependent Anion Channel 1 (VDAC1) as a Potential Biomarker of Gastric Cancer. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015;37:2339-2354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Gao W, Xu J, Wang F, Zhang L, Peng R, Shu Y, Wu J, Tang Q, Zhu Y. Plasma membrane proteomic analysis of human Gastric Cancer tissues: revealing flotillin 1 as a marker for Gastric Cancer. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Ong SE, Blagoev B, Kratchmarova I, Kristensen DB, Steen H, Pandey A, Mann M. Stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture, SILAC, as a simple and accurate approach to expression proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2002;1:376-386. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Marimuthu A, Subbannayya Y, Sahasrabuddhe NA, Balakrishnan L, Syed N, Sekhar NR, Katte TV, Pinto SM, Srikanth SM, Kumar P. SILAC-based quantitative proteomic analysis of gastric cancer secretome. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2013;7:355-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Wong JW, Cagney G. An overview of label-free quantitation methods in proteomics by mass spectrometry. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;604:273-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Liu H, Sadygov RG, Yates JR. A model for random sampling and estimation of relative protein abundance in shotgun proteomics. Anal Chem. 2004;76:4193-4201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1937] [Cited by in RCA: 1941] [Article Influence: 97.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Uen YH, Lin KY, Sun DP, Liao CC, Hsieh MS, Huang YK, Chen YW, Huang PH, Chen WJ, Tai CC. Comparative proteomics, network analysis and post-translational modification identification reveal differential profiles of plasma Con A-bound glycoprotein biomarkers in gastric cancer. J Proteomics. 2013;83:197-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Fan NJ, Li K, Liu QY, Wang XL, Hu L, Li JT, Gao CF. Identification of tubulin beta chain, thymosin beta-4-like protein 3, and cytochrome b-c1 complex subunit 1 as serological diagnostic biomarkers of gastric cancer. Clin Biochem. 2013;46:1578-1584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Ichikawa H, Yoshida A, Kanda T, Kosugi S, Ishikawa T, Hanyu T, Taguchi T, Sakumoto M, Katai H, Kawai A. Prognostic significance of promyelocytic leukemia expression in gastrointestinal stromal tumor; integrated proteomic and transcriptomic analysis. Cancer Sci. 2015;106:115-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Mann M, Jensen ON. Proteomic analysis of post-translational modifications. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:255-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1518] [Cited by in RCA: 1438] [Article Influence: 65.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Macek B, Mann M, Olsen JV. Global and site-specific quantitative phosphoproteomics: principles and applications. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2009;49:199-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 335] [Cited by in RCA: 324] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Harsha HC, Pandey A. Phosphoproteomics in cancer. Mol Oncol. 2010;4:482-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Glowinski F, Holland C, Thiede B, Jungblut PR, Meyer TF. Analysis of T4SS-induced signaling by H. pylori using quantitative phosphoproteomics. Front Microbiol. 2014;5:356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Holland C, Schmid M, Zimny-Arndt U, Rohloff J, Stein R, Jungblut PR, Meyer TF. Quantitative phosphoproteomics reveals link between Helicobacter pylori infection and RNA splicing modulation in host cells. Proteomics. 2011;11:2798-2811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Brockhausen I. Mucin-type O-glycans in human colon and breast cancer: glycodynamics and functions. EMBO Rep. 2006;7:599-604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 374] [Cited by in RCA: 409] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Song E, Mayampurath A, Yu CY, Tang H, Mechref Y. Glycoproteomics: identifying the glycosylation of prostate specific antigen at normal and high isoelectric points by LC-MS/MS. J Proteome Res. 2014;13:5570-5580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Zhang Y, Jiao J, Yang P, Lu H. Mass spectrometry-based N-glycoproteomics for cancer biomarker discovery. Clin Proteomics. 2014;11:18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Li K, Sun Z, Zheng J, Lu Y, Bian Y, Ye M, Wang X, Nie Y, Zou H, Fan D. In-depth research of multidrug resistance related cell surface glycoproteome in gastric cancer. J Proteomics. 2013;82:130-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Makridakis M, Vlahou A. Secretome proteomics for discovery of cancer biomarkers. J Proteomics. 2010;73:2291-2305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Schaaij-Visser TB, de Wit M, Lam SW, Jiménez CR. The cancer secretome, current status and opportunities in the lung, breast and colorectal cancer context. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1834:2242-2258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Abramowicz A, Wojakowska A, Gdowicz-Klosok A, Polanska J, Rodziewicz P, Polanowski P, Namysl-Kaletka A, Pietrowska M, Wydmanski J, Widlak P. Identification of serum proteome signatures of locally advanced and metastatic gastric cancer: a pilot study. J Transl Med. 2015;13:304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Loei H, Tan HT, Lim TK, Lim KH, So JB, Yeoh KG, Chung MC. Mining the gastric cancer secretome: identification of GRN as a potential diagnostic marker for early gastric cancer. J Proteome Res. 2012;11:1759-1772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646-674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51728] [Cited by in RCA: 47165] [Article Influence: 3368.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 53. | Bensimon A, Heck AJ, Aebersold R. Mass spectrometry-based proteomics and network biology. Annu Rev Biochem. 2012;81:379-405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 314] [Cited by in RCA: 308] [Article Influence: 23.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Chuang HY, Lee E, Liu YT, Lee D, Ideker T. Network-based classification of breast cancer metastasis. Mol Syst Biol. 2007;3:140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1146] [Cited by in RCA: 1019] [Article Influence: 56.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Vidal M, Cusick ME, Barabási AL. Interactome networks and human disease. Cell. 2011;144:986-998. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1475] [Cited by in RCA: 1196] [Article Influence: 85.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Johnson H, White FM. Quantitative analysis of signaling networks across differentially embedded tumors highlights interpatient heterogeneity in human glioblastoma. J Proteome Res. 2014;13:4581-4593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Yu CC, Yang JC, Chang YC, Chuang JG, Lin CW, Wu MS, Chow LP. VCP phosphorylation-dependent interaction partners prevent apoptosis in Helicobacter pylori-infected gastric epithelial cells. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Picotti P, Aebersold R, Domon B. The implications of proteolytic background for shotgun proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:1589-1598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Humphries JM, Penno MA, Weiland F, Klingler-Hoffmann M, Zuber A, Boussioutas A, Ernst M, Hoffmann P. Identification and validation of novel candidate protein biomarkers for the detection of human gastric cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1844:1051-1058. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Goh WQ, Ow GS, Kuznetsov VA, Chong S, Lim YP. DLAT subunit of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex is upregulated in gastric cancer-implications in cancer therapy. Am J Transl Res. 2015;7:1140-1151. [PubMed] |

| 61. | Lin LL, Hsia CR, Hsu CL, Huang HC, Juan HF. Integrating transcriptomics and proteomics to show that tanshinone IIA suppresses cell growth by blocking glucose metabolism in gastric cancer cells. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Qiao J, Cui SJ, Xu LL, Chen SJ, Yao J, Jiang YH, Peng G, Fang CY, Yang PY, Liu F. Filamin C, a dysregulated protein in cancer revealed by label-free quantitative proteomic analyses of human gastric cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2015;6:1171-1189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Diamandis EP. Towards identification of true cancer biomarkers. BMC Med. 2014;12:156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Tsai MM, Wang CS, Tsai CY, Chi HC, Tseng YH, Lin KH. Potential prognostic, diagnostic and therapeutic markers for human gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:13791-13803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Liu W, Yang Q, Liu B, Zhu Z. Serum proteomics for gastric cancer. Clin Chim Acta. 2014;431:179-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Lin LL, Huang HC, Juan HF. Discovery of biomarkers for gastric cancer: a proteomics approach. J Proteomics. 2012;75:3081-3097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Yang M, Zhong J, Zhao M, Wang J, Gu Y, Yuan X, Sang J, Huang C. Overexpression of nuclear apoptosis-inducing factor 1 altered the proteomic profile of human gastric cancer cell MKN45 and induced cell cycle arrest at G1/S phase. PLoS One. 2014;9:e100216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 68. | Guo T, Fan L, Ng WH, Zhu Y, Ho M, Wan WK, Lim KH, Ong WS, Lee SS, Huang S. Multidimensional identification of tissue biomarkers of gastric cancer. J Proteome Res. 2012;11:3405-3413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Hou Q, Tan HT, Lim KH, Lim TK, Khoo A, Tan IB, Yeoh KG, Chung MC. Identification and functional validation of caldesmon as a potential gastric cancer metastasis-associated protein. J Proteome Res. 2013;12:980-990. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 70. | Yang Y, Toy W, Choong LY, Hou P, Ashktorab H, Smoot DT, Yeoh KG, Lim YP. Discovery of SLC3A2 cell membrane protein as a potential gastric cancer biomarker: implications in molecular imaging. J Proteome Res. 2012;11:5736-5747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Cai XZ, Huang WY, Qiao Y, Du SY, Chen Y, Chen D, Yu S, Che RC, Liu N, Jiang Y. Inhibitory effects of curcumin on gastric cancer cells: a proteomic study of molecular targets. Phytomedicine. 2013;20:495-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Hu CW, Tseng CW, Chien CW, Huang HC, Ku WC, Lee SJ, Chen YJ, Juan HF. Quantitative proteomics reveals diverse roles of miR-148a from gastric cancer progression to neurological development. J Proteome Res. 2013;12:3993-4004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Zhang ZQ, Li XJ, Liu GT, Xia Y, Zhang XY, Wen H. Identification of Annexin A1 protein expression in human gastric adenocarcinoma using proteomics and tissue microarray. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:7795-7803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Aquino PF, Lima DB, de Saldanha da Gama Fischer J, Melani RD, Nogueira FC, Chalub SR, Soares ER, Barbosa VC, Domont GB, Carvalho PC. Exploring the proteomic landscape of a gastric cancer biopsy with the shotgun imaging analyzer. J Proteome Res. 2014;13:314-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Wu JY, Cheng CC, Wang JY, Wu DC, Hsieh JS, Lee SC, Wang WM. Discovery of tumor markers for gastric cancer by proteomics. PLoS One. 2014;9:e84158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Shen XJ, Zhang H, Tang GS, Wang XD, Zheng R, Wang Y, Zhu Y, Xue XC, Bi JW. Caveolin-1 is a modulator of fibroblast activation and a potential biomarker for gastric cancer. Int J Biol Sci. 2015;11:370-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Chen J, Ge L, Liu A, Yuan Y, Ye J, Zhong J, Liu L, Chen X. Identification of pathways related to FAF1/H. pylori-associated gastric carcinogenesis through an integrated approach based on iTRAQ quantification and literature review. J Proteomics. 2016;131:163-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |