Published online Jan 7, 2016. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i1.379

Peer-review started: May 31, 2015

First decision: July 14, 2015

Revised: September 14, 2015

Accepted: November 9, 2015

Article in press: November 9, 2015

Published online: January 7, 2016

Processing time: 217 Days and 16.3 Hours

Proteoglycans are a group of molecules that contain at least one glycosaminoglycan chain, such as a heparan, dermatan, chondroitin, or keratan sulfate, covalently attached to the protein core. These molecules are categorized based on their structure, localization, and function, and can be found in the extracellular matrix, on the cell surface, and in the cytoplasm. Cell-surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans, such as syndecans, are the primary type present in healthy liver tissue. However, deterioration of the liver results in overproduction of other proteoglycan types. The purpose of this article is to provide a current summary of the most relevant data implicating proteoglycans in the development and progression of human and experimental liver cancer. A review of our work and other studies in the literature indicate that deterioration of liver function is accompanied by an increase in the amount of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans. The alteration of proteoglycan composition interferes with the physiologic function of the liver on several levels. This article details and discusses the roles of syndecan-1, glypicans, agrin, perlecan, collagen XVIII/endostatin, endocan, serglycin, decorin, biglycan, asporin, fibromodulin, lumican, and versican in liver function. Specifically, glypicans, agrin, and versican play significant roles in the development of liver cancer. Conversely, the presence of decorin could potentially provide protective effects.

Core tip: Proteoglycans are molecules that contain at least one glycosaminoglycan chain and are primarily found on the cell surface and in the extracellular matrix, where they serve as structural components. In addition, their glycosaminoglycan chains interact with numerous regulatory molecules, thus potentially influencing a myriad of cellular processes, including those linked with cancer development. For example, they can support or inhibit signaling of growth factors, cytokines, and hormones. This article reviews current data demonstrating the versatile role of proteoglycans in the development, maintenance, and progression of liver cancer.

- Citation: Baghy K, Tátrai P, Regős E, Kovalszky I. Proteoglycans in liver cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2016; 22(1): 379-393

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v22/i1/379.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i1.379

Proteoglycans are molecules with glycosaminoglycan (GAG) chains covalently attached to the protein core and are typically found on the cell surface or in the extracellular matrix (ECM). They were believed to be responsible for the maintenance of tissue turgor in the interstitial matrix, and were thought to act as molecular sieves in basement membranes. Although their sugar chains hindered the determination of their exact structure[1,2], gene technologies introduced in the second part of the last century provided a clearer picture. DNA sequencing of the regions encoding the protein cores led to the identification of glycanation sites. It then became possible to classify proteoglycans, initially based on sugar chains, and then subsequently by protein structure and function. It became clear that both the sugar chains and the protein cores of proteoglycans possess distinct and well-determined functions that are independent of each other.

The GAG chains of proteoglycans are comprised of repeating disaccharide units, each containing a uronic acid and an acetylated or sulfated hexosamine (D-glucosamine, N-acetyl-D-glucosamine, or N-acetyl-D-galactosamine). The length of these chains is variable, though the number of chains that attach to the protein core is determined by the number of sugar attachment sites, marked by Ser-Gly dipeptide motifs. Whereas the backbone of heparan sulfate (HS) is comprised of glucuronic acid and N-acetyl-D-glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate (CS) contains glucuronic acid and N-acetyl-galactosamine, and dermatan sulfate (DS) contains iduronic acid and N-acetyl-galactosamine. Instead of uronic acid, keratan sulfate (KS) contains sulfated galactose with N-acetyl-glucosamine residues. Partial sulfation of D-glucosamine residues in HS chains create a domain structure of alternating N-acetylated and N-sulfated regions. The latter can potentially interact with growth factors, cytokines, growth factor receptors, lipoproteins, and viruses, among others.

With the classification of proteoglycans (Table 1), it became evident that CS and DS proteoglycans primarily reside within the connective tissue ECM (bone, joints, tendons), whereas a considerable number of HS proteoglycans reside on the cell surface. Currently, more than 40 proteoglycans have been discovered, though only a few have been studied in the liver. This review describes what is currently known about the proteoglycans, with particular focus on the role of these molecules in the healthy and cancerous liver.

| Localization | Eponym | Gene symbol | GAG |

| Intracellular | Serglycin | SRGN | Hep |

| Membrane | |||

| SLIPs | |||

| Syndecan-1 | SDC1 | HS/CS | |

| Syndecan 2-4 | SDC2-4 | HS | |

| GRIPs | |||

| Glypican 1-6 | GPC 1-6 | HS/CS | |

| Other | |||

| Betaglycan | TGFBR3 | HS/CS | |

| CD44 | CD44 | CS | |

| Extracellular | |||

| SLRPs | |||

| Class I | |||

| Decorin | DCN | DS/CS | |

| Biglycan | BGN | CS | |

| Asporin | ASPN | - | |

| Class II | |||

| Fibromodulin | FMOD | KS | |

| Lumican | LUM | KS | |

| Keratocan | KERA | KS | |

| PRELP | PRELP | - | |

| Osteoadherin | OMD | KS | |

| Class III | |||

| Epiphycan | EPYC | CS/DS | |

| Osteoglycin | OGN | - | |

| Pericellular | |||

| BM zone | |||

| Agrin | AGRN | HS | |

| Collagen XVIII | COL18A1 | HS | |

| Aggrecan | ACAN | CS/KS | |

| Hyalectans | |||

| Versican | VCAN | CS | |

| Neurocan | NCAN | CS | |

| Brevican | BCAN | CS |

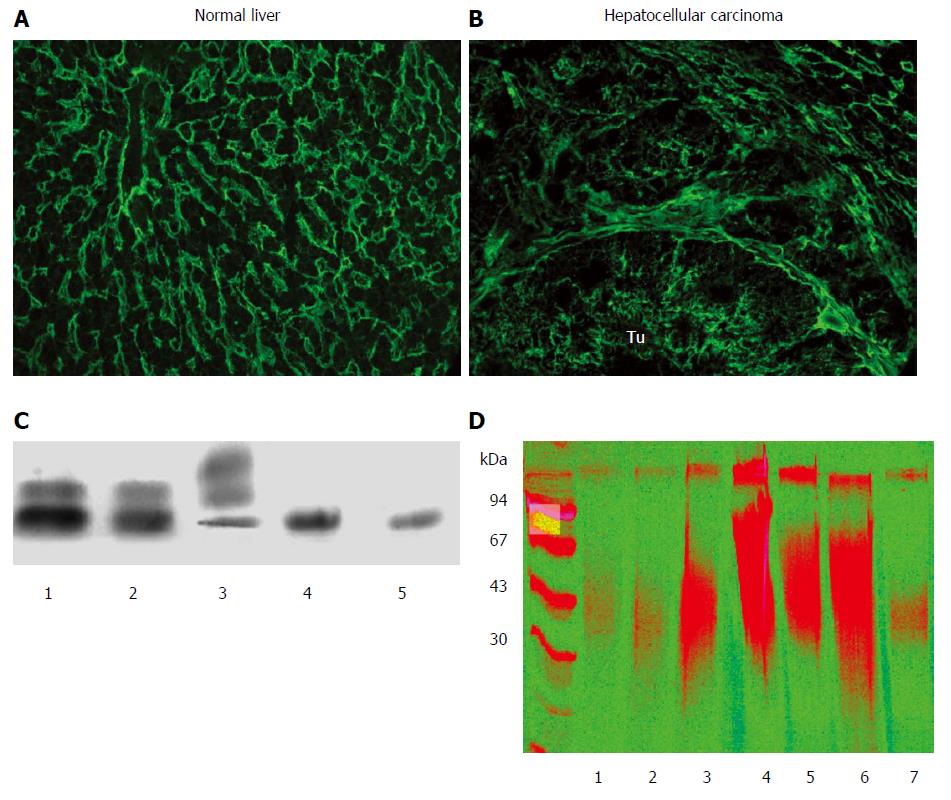

As a parenchymal organ, the liver contains a limited amount of stromal components. As a result, HS would likely be the major GAG present on the surface of hepatocytes in normal conditions. Indeed, immunohistochemical analyses demonstrate positivity with anti-HS antibodies along the sinusoids and on the surface of hepatocytes[3]. Moreover, electrophoresis of GAGs isolated from normal human liver confirms that the majority of GAG chains are HS, with additional minor amounts of DS; CS is barely detectable (Figure 1).

The development of liver cancer is accompanied by dramatic changes in both the quantity and the composition of liver GAGs. The most conspicuous change is a 20-fold increase in CS, though enhancement of other GAGs has also been observed (Figure 1)[4]. This progressive increase in CS is accompanied by a relative decrease in HS[5]. Surprisingly, there is also a substantial increase in the amount of GAG components that appear in the seemingly normal peritumoral tissue. The alteration of GAG composition is a consequence of remodeled proteoglycan profiles, though it is not known which types are responsible. Glypican-3 and agrin are the two major HS proteoglycan components in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), while the source of CS in liver cancer is presumably versican.

It has been reported that, unlike in normal liver, HS obtained from cancerous liver is undersulfated[6]. However, in our own experiments, although we observed a modest but significant decrease in 6-O sulfation and an increase in 3-O sulfation, total HS sulfation levels did not differ between normal liver and HCC[7]. This implies that any observed functional differences are likely based on more subtle structural alterations, such as those affecting the relationship between sulfated and acetylated domains. In addition, HSs isolated from HCC are increased in size compared to those isolated from the apparently normal peritumoral tissue[8]. It is likely that there are additional, as of yet undetermined, alterations responsible for the functional changes[9].

The diversity of ligand-binding properties on cell-surface HS proteoglycans derives from the intricate and diverse structures of their sugar chains[10]. Tyrosine kinase receptor ligands can bind with cell-surface HS to form a ternary receptor complex. At the same time, free HS proteoglycans in the ECM can compete for these binding partners, thereby creating a soluble factor concentration gradient within the pericellular space. Moreover, many growth factors can bind HS, including basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), hepatocyte, platelet-derived, and vascular endothelial growth factors, and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β[11-13]. Interactions between HS and cytokines, such as regulated on activation normal T cell expressed and secreted (RANTES; also known as CCL5) and stromal cell-derived factor 1 (also known as CXCL12), have been implicated in hepatoma cell line invasion[14,15].

One of the best-known etiologic factors of HCC is hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Importantly, it has been shown that of HSs prepared from various bovine tissues, only those from the liver have a high affinity for E1 and E2, the envelope glycoproteins of HCV[16]. These data suggest that surface HS proteoglycans on liver cells are responsible for the liver-specific tissue tropism of HCV infection.

HSs extracted from healthy liver tissue can inhibit topoisomerase I and II activity[9,17] and compete with DNA for binding to several transcription factors (AP1, Ets1, TFIID, and Sp1), whereas HSs obtained from HCC do not[8]. This is important, as labeled HS proteoglycans have been shown to enter the nucleus of hepatoma cells[8]. Although the mechanism for this nuclear translocation is not known, complex formation with growth factors such as bFGF may facilitate this. Furthermore, recent data show that free or protein core-bound HSs are capable of inhibiting histone deacetylase activity, such as with syndecans shed from tumors that are taken up by stromal cells[18,19].

Syndecans are a family of molecules comprised of three domains, including highly conserved intracellular and transmembrane domains and an extracellular domain that is unique to each member. The extracellular domain carries three HS chains, but a single CS chain can also be present on the core protein[20]. Syndecan-1, the most widely studied of the syndecans, is found in low amounts on the basolateral surface of hepatocytes. It is likely to be the major cell-surface HS proteoglycan in healthy liver tissue. HS chains of syndecan-1 confer all the aforementioned functions that characterize HSPGs in general. In addition it has been shown to play a critical role in lipoprotein clearance, acting as a low-density lipoprotein receptor on hepatocytes[21].

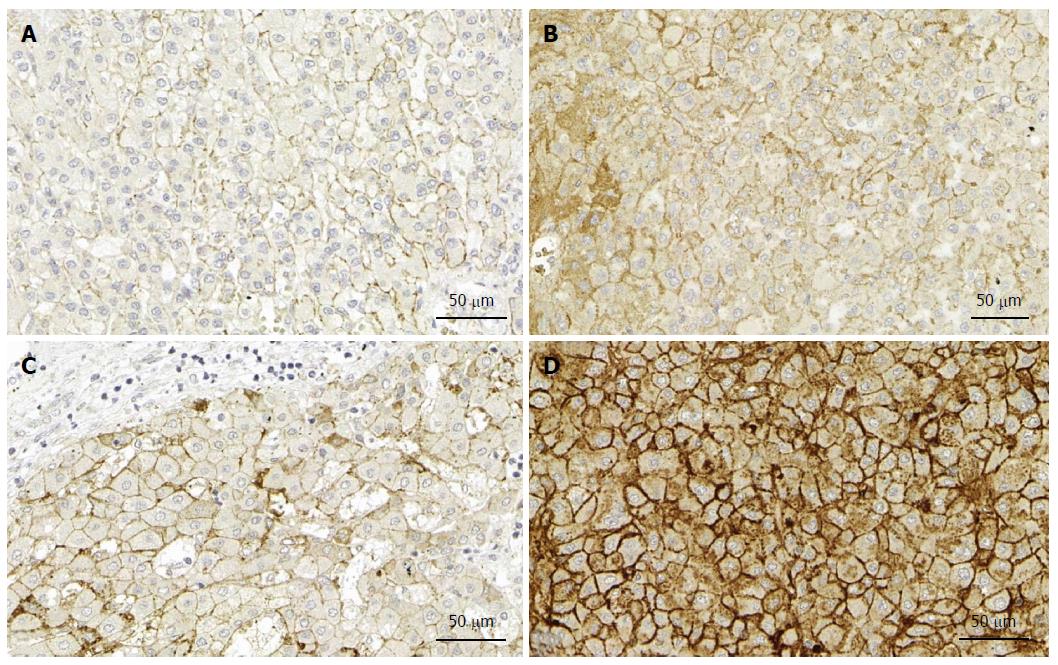

Although syndecan-1 expression is upregulated in human liver cirrhosis, our immunohistochemical analyses failed to reveal tumor-specific changes in liver cancer (unpublished data) (Figure 2). Thus, elevated syndecan-1 expression appears to be more closely associated with liver cirrhosis, rather than malignant transformation. Consistent with this idea, mRNA expression of syndecan-1 was decreased in 12 HCC samples[22], and the protein expression was low in 57 patients with invasive HCC[23].

It is important to note that the modest changes observed in syndecan-1 on the surface of hepatoma cells are likely underestimating the true effect, as a considerable proportion of syndecan-1 is shed from the cell surface. This shedding can be detected as an increased serum concentration, which also correlates with advanced Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage, and therefore associated with the progression of HCC[24] and a greater risk of death[25]. As a result, expression of syndecan-1 on the surface of hepatoma cells does not reflect the role this molecule plays in the progression of liver cancer. The importance of shedding is highlighted by the work of Ramani et al[26], who demonstrated the importance of heparanase in the modification of HS chains and shedding of syndecan-1, which triggered the production of matrix metalloproteases. Furthermore, our unpublished data indicate that inhibition of syndecan-1 shedding in HepG2 cells induces cell differentiation via downregulation of the transcription factor Ets-1 and the major sheddase MMP7. Additional in vitro experiments indicate that specific domains of syndecan-1 exert particular effects on hepatoma cells, as HepG2 and Hep3B cells expressing a truncated form of syndecan-1 (in which the extracellular domain contains only the four membrane-proximal amino acids) are induced to differentiate (unpublished data).

Glypicans (GPCs) are a family of six medium-sized HS proteoglycans that are tethered to the cell surface with a GPI anchor. These proteins share conserved structural features, including insertion of two to four HS chains close to the membrane, and are considered regulators of Wnt, Hedgehog, FGF, and bone morphogenetic protein signaling[27]. Although the roles of GPC-1 and GPC-5 have also been investigated in development and cancer[28-31], GPC-3 is by far the most thoroughly studied member of this family, and appears to be a key driver of hepatocarcinogenesis. Mutations of GPC-3 were first described in Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndrome, an X-linked disorder characterized by pre- and postnatal overgrowth[32]. As these were loss-of-function mutations, it was hypothesized that the function of GPC-3 is to suppress tissue growth. In the following years, GPC-3 became increasingly implicated in cancer, and is now regarded as a typical oncofetal protein that is widely expressed during development, but silenced in adult tissues.

GPC-3 expression is elevated in several cancer types, such as embryonic tumors[33,34], malignant melanoma[35], and, most notably, HCC[36,37]. On the other hand, it is downregulated in malignant mesothelioma and ovarian cancer[38,39], and silenced via promoter hypermethylation in the majority of breast cancers[40,41]. The effects of GPC-3, such as the growth-inhibitory potential, have been associated with the negative regulation of Hedgehog signaling[42]. Conversely, GPC-3 may also stimulate cell proliferation by enhancing activity of the Wnt pathway. Stabilization of Wnt binding to its receptor, Frizzled, appears to be pivotal in promoting hepatocarcinogenesis[43]. It was also recently shown that GPC-3 promotes the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and invasive behavior of HCC cells through the stimulation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)[44].

GPC-3 is not expressed in the normal liver[45], and overexpression in this organ is restricted to malignant hepatocellular lesions[36,46,47]. Because of this, positivity for GPC-3[48,49], along with arginase-1, CD34, glutamine synthetase, HepPar1, and heat shock protein-70[50-53], are utilized in immunohistochemical analyses for the diagnosis of HCC. Indeed, the use of various combinations of these markers when analyzing problematic samples, such as core biopsies and fine-needle aspiration specimens, can aid in resolving diagnostic dilemmas, such as distinguishing small well-differentiated HCC from dysplastic nodules[51,52,54]. Furthermore, GPC-3 can be used as a serum marker, as it is cleaved from the cell surface by the lipase notum[55]. However, GPC-3 should not be relied upon as a single serum marker, as it has only moderate accuracy in this application[37,56]. Nevertheless, GPC-3 is an attractive therapeutic target for liver cancer because of its high expression in the majority of HCCs and its known oncogenic role via Wnt and ERK signaling. As such, several preclinical and clinical studies have been initiated to test the efficacy of GPC-3-specific antibodies in advanced HCC patients. Although a promising candidate, the humanized mouse antibody GC33 recently failed in a phase II trial (Yen et al, J Clin Oncol 2014; 32 Suppl 5; abstr 4102), others are still in development[57]. Additionally, immunotherapy with T cells bearing chimeric-antigen receptors specific for GPC-3 is currently being tested in a phase I clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT02395250).

Agrin is a large, multidomain proteoglycan with a about 220 kDa protein core that is both N-glycosylated and heavily O-glycanated with HS (and, to a lesser extent, CS) chains, thus rendering its apparent molecular mass > 400 kDa. Alternative splicing of the C-terminal exons imparts acetylcholine receptor clustering functionality, which was the first known role of agrin[58]. In addition, the use of alternative promoter sequences lead to tissue-specific expression of secreted and membrane-bound isoforms. Agrin cross-links the cytoskeleton of cells with the ECM, where it interacts with laminins and cell-surface receptors, including integrins, α-dystroglycan, and the lipoprotein-related receptor 4/muscle-specific kinase complex[58,59]. Like other HS proteoglycans, agrin binds to and regulates growth factors such as bone morphogenetic proteins and TGF-β1[60].

Since its discovery as a key motoneuron-derived synaptic organizer at the neuromuscular junction[61], agrin has been described in numerous other anatomic locations and physiologic roles. For example, in addition to also organizing central nervous system synapses[62], agrin was found to orchestrate the formation of the so-called “immunologic synapse” between T cells and their antigen-presenting partners[63]. Furthermore, agrin has recently emerged as a key component of the hematopoietic stem cell niche and the matrix of peripheral lymphoid organs[64,65], and was identified as a cell-autonomous survival factor for monocytes[66]. The secreted isoform is present in specialized basal laminae, such as capillary and alveolar walls of the lung, the renal glomerular basement membrane, and the blood-brain barrier[67-70], and may be a major HS proteoglycan constituent of larger blood vessels[71].

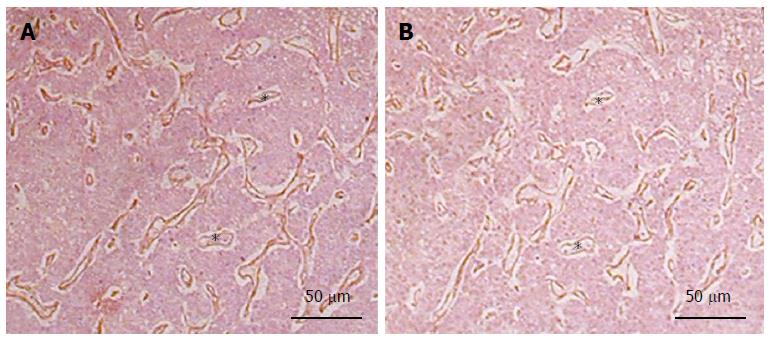

As it is expressed only in the walls of portal arteries and the biliary compartment (comprising both mature bile ducts and the hepatic progenitor cell niche), agrin was not initially detected in healthy liver tissue[72-74]. In contrast, levels of agrin are dramatically elevated in chronic liver disease, such as cirrhosis, where it is observed in reactive bile ductules and arterial walls, and in the tumor microvasculature of HCC[73]. Indeed, its presence in tumor microvessels reliably differentiates HCC from non-malignant lesions (where it is absent), such as adenomas and dysplastic nodules, and cholangiocellular and metastatic adenocarcinomas. In non-hepatocellular adenocarcinomas, agrin is detected in pseudoglandular basement membranes rather than microvascular walls[75,76].

The origin of agrin in liver cancer and its roles in HCC progression remain unknown. However, a recent report found that multiple HCC cell lines highly express and secrete agrin[77]. In these cell lines, agrin promoted proliferation, migration, invasion, and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition via the lipoprotein-related receptor 4/muscle-specific kinase complex and focal adhesion signaling. Similar protumorigenic effects of agrin (and perlecan) were also observed in oral squamous cell carcinoma[78]. Of note, the microvascular basement membrane where most agrin resides in HCC contacts other cell types in addition to the tumor cells, including endothelial cells and pericytes, which also contribute to the ECM. Furthermore, these cell types (i.e., cultured rat hepatic myofibroblasts corresponding to pericytes and endothelial cells from the human umbilical vein) have also been shown to produce agrin[73,79]. It is important to acknowledge the potential for additional functions of agrin. For example, agrin may modulate vascular barrier properties of the endothelial basement membrane by reorganizing junctional complexes[80].

Perlecan is another large, multidomain HS proteoglycan that is synthesized by hepatic stellate cells and endothelial cells and is present in basement membranes of blood vessels and bile ducts in the portal area, as well as along the sinusoids[81]. It is structurally similar to agrin, and a transmembrane variant has also been described[82,83]. The primary functions assigned to perlecan have been attributed to the growth factor-binding HS chains, though the modular protein core also participates in numerous cell-matrix and matrix-matrix interactions[84].

Perlecan deposition is enhanced by sinusoidal capillarization during fibrogenesis[81]. In liver cancer, it becomes a component of the tumorous stroma, where it colocalizes with bFGF, indicating a possible role in tumor neoangiogenesis (Figure 3). Indeed, perlecan is known to play a central role in pathologic angiogenesis based on the high capacity of its HS chains to bind the two major proangiogenic factors, vascular endothelial growth factor and bFGF[85]. Intriguingly, perlecan can also inhibit angiogenesis via its C-terminal proteolytic fragment, termed endorepellin[86]. Endorepellin binds to the master matrix receptor α2β1-integrin on endothelial cells, triggering disruption of the cytoskeleton and blockade of migration and survival[87]. Nevertheless, there are experimental and clinical data demonstrating the proangiogenic role of perlecan in human malignancies, where it promotes tumor progression in carcinomas of the breast, prostate, and colon, as well as in metastatic melanoma[88]. Thus, perlecan is also likely to favor neovessel formation in HCC progression, though this has not yet been specifically examined.

Collagen XVIII is a large basement membrane molecule that shares features with both collagens and proteoglycans. As a proteoglycan, collagen XVIII harbors several HS GAG attachment sites. At the same time, it is structurally similar to collagen XV[89,90], and has three variant forms that arise due to alternative transcription and splicing. Short variants of collagen XVIII are synthesized by the bile duct epithelial, endothelial, and vascular smooth muscle cells, and are primarily expressed in vascular, epithelial, muscle fiber, and peripheral nerve basement membranes. Long variants are mainly produced by hepatocytes and deposited in the perisinusoidal space. However, activated hepatic stellate cells also produce the short collagen XVIII variant during fibrogenesis, which then becomes a major component of the altered basement membrane in capillarized sinusoids[91] and of the ECM in primary and metastatic liver cancers[92]. At the same time, the mRNA levels of collagen XVIII are decreased in liver cancer, and have been associated with larger tumor size, higher microvessel density, and recurrence after tumor resection[93]. It has been proposed that a decrease in the long variant, which contains a domain homologous to the Wnt-binding Frizzled receptor, favors tumor progression in HCC[92,94] by promoting activation of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway[95].

The C-terminal domain of collagen XVIII can be cleaved by several proteases, including MMP-3, -7, -9, -13, -20, elastase, and cathepsin L, producing a proteolytic fragment called endostatin, which has a strong antiangiogenic effect[90]. Endostatin influences several signaling pathways, including vascular endothelial growth factor, Wnt/β-catenin, and α5β1-integrin, which are known to play crucial roles in hepatocarcinogenesis. Exogenous administration of endostatin has also been shown to inhibit tumor growth in various tissues, as well as HCC[96]. These features led to the use of endostatin as a therapeutic agent for cancer in phase I and II clinical trials, though the results were less promising than were found in preclinical experiments. Nevertheless, as stable disease and regression were observed in several cases, the use of a modified form of endostatin has continued in certain countries for the treatment of lung and gastric cancers[97]. Additionally, endostatin can be detected in serum, and therefore could be used for predicting prognosis[93,98]. For example, preoperative serum endostatin is inversely correlated with microvessel density in HCC patients and is related to a better prognosis after resection[93].

Endocan, a proteoglycan whose core protein is glycanated by a single DS chain, is typically produced by endothelial cells[99]. Endocan is not normally expressed in highly vascularized organs such as the liver, but is rather synthesized upon inflammation and malignant transformation, indicating that it may be a characteristic feature of activated endothelial cells[100]. In liver cancer, endocan expression is confined to the microvessels of the tumor tissue, but is not present in capillaries in the peritumoral liver[101]. The DS chain of endocan has a high affinity for hepatocyte growth factor, an interaction that is critical for the activation of the Met receptor, which stimulates proliferation of hepatoma cells[100].

When analyzing the factors associated with clinicopathologic characteristics of HCC tumors, it was found that endocan-positive, but not CD34-positive, microvessel density was strongly correlated with microscopic venous invasion, a reliable indicator of postoperative recurrence[101]. Increased production of endocan can be detected in serum, which also can be used as a prognostic indicator, as it is associated with poor hepatic function, a greater number of tumors, and vascular invasion[102].

One of the first to be sequenced, serglycin is the only proteoglycan with intracellular localization. Another unique feature of serglycin is that it has heparin as a sugar side chain, which allows it to interact with a variety of inflammatory mediators, such as proteases, cytokines, and growth factors[103,104]. Serglycin is mainly produced by hematopoietic cells, and it was only recently discovered that it is also expressed by tumor cells, where it promotes their aggressive behavior[104]. Consistent with this, overexpression of serglycin in HCC is predictive of a poor prognosis, with increasing levels corresponding to advanced Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging, vascular invasion, and early recurrence[105]. In addition, the increased level of serglycin correlates with elevated vimentin and reduced E-cadherin levels, and is therefore thought to induce epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in HCC[105].

Small leucine-rich proteoglycans (SLRPs) represent the largest family of proteoglycans, with 18 distinct gene products and several splice variants. Members of this proteoglycan family are characterized by a relatively small core protein comprised of a central region of leucine-rich repeats[103,106]. Although most SLRP members carry CS/DS or KS chains, there are a few that lack GAG chains, and are thus only classified as proteoglycans based on their structural and functional homology with other SLRP members[91,103,107].

Decorin is the prototypical member of the SLRP family, and is glycanated with either a single CS or DS chain[106,108]. Primarily expressed by fibroblasts and myofibroblasts among various tissue types, decorin is most abundant in the skin, connective tissues, muscles, and the kidney[109]. Indeed, it was named based on its “decoration” of collagen fibers through binding to collagen I where it regulates fibril formation and stabilization[110,111]. However, it is also known to be involved in many biologic and physiologic processes, including cell proliferation and differentiation, via interaction with various growth factors, matrix constituents, and signal transduction pathway-coupled receptors, such as those known to be dysregulated in HCC[112]. Therefore, soluble forms of decorin may act as pan-receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors, targeting receptors for epidermal growth factor, HGF, insulin-like growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, and platelet-derived growth factor[108,113-121]. Interactions with such receptors can also lead to decorin-induced caveosomal internalization and receptor degradation[122].

In the healthy liver, decorin levels are generally low, with the exception of the central veins and the portal tracts where expression is higher. Some expression has also been detected in the sinusoidal walls. However, decorin accumulates with increased connective tissue production in chronic liver injury and is deposited along the sinusoidal walls as capillarization occurs, though its appearance often precedes the accumulation of fibrillar collagens. Furthermore, decorin colocalizes with high amounts of TGF-β1, a key stimulator of fibrillogenesis, in fibrotic areas in cases of chronic hepatitis, fibrosis, and cirrhosis[123]. Indeed, decorin has been shown to directly bind to and regulate TGF-β1[124,125], as well as indirectly via association with the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein receptor[126]. Through similar interactions, decorin can inhibit TGF-β1-dependent proliferation of fibroblasts, production of matrix in experimental renal fibrogenesis[127], and collagen synthesis in hepatic stellate cells[128]. Moreover, decorin-deficient mice exhibit increased susceptibility to thioacetamide-induced fibrogenesis, as well as enhanced connective tissue deposition and significantly higher TGF-β1 bioactivity compared to their wild-type counterparts[129]. The lack of decorin also impeded the resolution of severe fibrosis, which may have been due to impaired matrix metalloprotease action. In addition, in vitro experiments demonstrated that knockdown of decorin in the LX2 hepatic stellate cell line increased the expression of smooth muscle actin and collagen type I. These observations support the notion that decorin could be utilized as an anti-TGF-β1 agent in the treatment of chronic liver diseases[130]. However, it is important to note that decorin can be present in both soluble and collagen-bound pools, which could potentially modulate its antifibrogenic activity.

The observation that decorin can affect multiple signaling pathways dysregulated in HCC[112], along with its ability to downregulate β-catenin and Myc expression[131] with concurrent induction of p21WAF1/CIP1[132], indicates that decorin may serve as a tumor suppressor in liver cancer. In support of this role, levels of decorin mRNA are reportedly downregulated in HCC[133,134], and decorin was found to inhibit proliferation of HuH7[135] and HepG2 hepatoma cells via induction of p21WAF1/CIP1 and p57KIP2[136,137], while enhancing apoptosis[135-137]. Furthermore, virus-mediated transfection of decorin causes death of xenografted HCC cells[138].

Interestingly, well-defined deposits of decorin surround tumor foci in experimental models of hepatocarcinogenesis[139]. At the same time, decorin production is decreased in the majority of human hepatoma stroma cells within the tumor tissue, while the expression is increased in the surrounding connective tissue (unpublished data). Furthermore, an inverse correlation exists between decorin expression and aggressive HCC behavior, as ablation of the decorin gene results in enhanced tumor formation in primary hepatocarcinogenesis models, likely due to enhanced receptor tyrosine kinase signaling and failed p21WAF1/CIP1 induction[119,139]. Indeed, increased phosphorylation of epithelial and platelet-derived growth factor receptors, macrophage stimulating protein receptor, and insulin-like growth factor receptor was observed with decorin deletion[139].

Biglycan is a member of the SLRP family that is produced by activated hepatic stellate cells during fibrogenesis[140,141]. Biglycan is deposited along with decorin in fibrotic areas[142], and similarly interacts with members of the TGF-β/bone morphogenetic protein family[107]. However, mechanistic details of its contribution to liver diseases have not yet been elucidated[91].

Asporin is a proteoglycan that is very similar in structure to decorin and biglycan, though it does not contain any GAG chains[143,144]. Its name is derived from its aspartic acid-rich N-terminal region and its overall homology and similar tissue distribution to decorin. Although it is not expressed in normal liver tissue[143,144], levels of asporin are upregulated in cancer-associated fibroblasts in gastric carcinoma[145]. Moreover, asporin can interfere with TGF-β/Smad signaling[146], and therefore may potentially play a role in liver malignancies.

Fibromodulin and lumican are SLRPs that contain KS GAG chains. Although not detectable in normal liver, expression of these proteoglycans is induced during liver fibrogenesis[147]. Fibromodulin was shown to promote the profibrogenic potential of hepatic stellate cells[148], and lumican was found to be a prerequisite for hepatic fibrosis[149]. However, the role of these specific SLRPs in hepatocarcinogenesis has not yet been determined.

Versican is a member of the hyaluronic acid-binding proteoglycan group that contains CS and DS GAG side chains, and is a ubiquitous component of the interstitial stroma ECM. Its four splice variants (V0, V1, V2, and V3) all have N-terminal and C-terminal globular domains responsible for various molecular interactions, and may or may not contain two GAG binding domains (GAGα and GAGβ). In adult tissues, the V2 variant is the most frequent, which contains the CS GAGβ binding domain. The number of CS/DS chains varies among the variants, whereas the number, length, and molecular structure of the GAG chains are influenced by the N-terminal and C-terminal globular domains[150]. Synthesis of versican is primarily stimulated by TGF-β1[151-153], but also by platelet-derived growth factor and interleukin 1α, whereas its production is inhibited by interleukin 1β[154,155].

In the ECM, versican interacts with various partners, such as tenascin-R, fibulin-1[156-158], fibrillin-1[157], fibronectin[159], P- and L-selectin[160,161], and various chemokines[150] via the globular domains or GAG chains. In addition, versican has been shown to bind to the epidermal growth factor receptor[150], and to the cell-surface proteins CD44[160] and integrin β1[162]. Recently, versican has been shown to act on macrophages through toll-like receptors (TLR2 and TLR6), and promote inflammatory cytokine production and tumor cell metastasis[163]. The ability of versican to interact with a variety of regulatory components and cell-surface molecules indicates that versican could potentially influence cell adhesion, proliferation, apoptosis, migration, and invasion[164-167].

Elevated expression of versican (V0 and V1 variants) has been found in numerous types of malignancies, including breast and prostate cancers, gliomas, osteosarcomas, fibrosarcomas, and melanomas, where it is associated with cancer relapse and poor patient outcome[168-174]. Recent studies show that expression of versican is regulated by a number of microRNAs[175,176]. Interestingly, the 3’UTR of versican can bind to and antagonize some of these microRNAs, thereby enhancing its own expression[177]. Indeed, transgenic mice expressing the 3’UTR region of versican develop HCC[178], demonstrating a possible role for versican expression in hepatocarcinogenesis. However, versican was not detected in tumor cells in immunohistochemical analyses from a large cohort of human HCC specimens[179]. Thus, further study is needed to confirm the role of versican in liver cancer.

Proteoglycans can be found on the cell surface and in the extracellular matrix. Their GAG chains interact with numerous regulatory molecules and signaling pathways, including growth factors, cytokines, and hormones, thus affording the potential to influence a myriad of cellular processes, including those linked with cancer development. There is clear evidence that proteoglycan composition changes with liver cancer development, and thus proteoglycans provide targets for potential therapeutic agents and diagnostic biomarkers.

P- Reviewer: Wirth TC S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Fransson LA, Havsmark B, Chiarugi VP. Co-polymeric glycosaminoglycans in transformed cells. Transformation-dependent changes in the co-polymeric structure of heparan sulphate. Biochem J. 1982;201:233-240. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Kjellén L, Lindahl U. Proteoglycans: structures and interactions. Annu Rev Biochem. 1991;60:443-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1409] [Cited by in RCA: 1409] [Article Influence: 41.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Roskams T, Moshage H, De Vos R, Guido D, Yap P, Desmet V. Heparan sulfate proteoglycan expression in normal human liver. Hepatology. 1995;21:950-958. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Kovalszky I, Pogany G, Molnar G, Jeney A, Lapis K, Karacsonyi S, Szecseny A, Iozzo RV. Altered glycosaminoglycan composition in reactive and neoplastic human liver. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;167:883-890. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Lv H, Yu G, Sun L, Zhang Z, Zhao X, Chai W. Elevate level of glycosaminoglycans and altered sulfation pattern of chondroitin sulfate are associated with differentiation status and histological type of human primary hepatic carcinoma. Oncology. 2007;72:347-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nakamura N, Kojima J. Changes in charge density of heparan sulfate isolated from cancerous human liver tissue. Cancer Res. 1981;41:278-283. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Tátrai P, Egedi K, Somorácz A, van Kuppevelt TH, Ten Dam G, Lyon M, Deakin JA, Kiss A, Schaff Z, Kovalszky I. Quantitative and qualitative alterations of heparan sulfate in fibrogenic liver diseases and hepatocellular cancer. J Histochem Cytochem. 2010;58:429-441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Dudás J, Ramadori G, Knittel T, Neubauer K, Raddatz D, Egedy K, Kovalszky I. Effect of heparin and liver heparan sulphate on interaction of HepG2-derived transcription factors and their cis-acting elements: altered potential of hepatocellular carcinoma heparan sulphate. Biochem J. 2000;350 Pt 1:245-251. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Kovalszky I, Dudás J, Oláh-Nagy J, Pogány G, Töváry J, Timár J, Kopper L, Jeney A, Iozzo RV. Inhibition of DNA topoisomerase I activity by heparan sulfate and modulation by basic fibroblast growth factor. Mol Cell Biochem. 1998;183:11-23. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Kreuger J, Spillmann D, Li JP, Lindahl U. Interactions between heparan sulfate and proteins: the concept of specificity. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:323-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 366] [Cited by in RCA: 390] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lyon M, Deakin JA, Mizuno K, Nakamura T, Gallagher JT. Interaction of hepatocyte growth factor with heparan sulfate. Elucidation of the major heparan sulfate structural determinants. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:11216-11223. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Tumova S, Woods A, Couchman JR. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans on the cell surface: versatile coordinators of cellular functions. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2000;32:269-288. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Jakobsson L, Kreuger J, Holmborn K, Lundin L, Eriksson I, Kjellén L, Claesson-Welsh L. Heparan sulfate in trans potentiates VEGFR-mediated angiogenesis. Dev Cell. 2006;10:625-634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 197] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Friand V, Haddad O, Papy-Garcia D, Hlawaty H, Vassy R, Hamma-Kourbali Y, Perret GY, Courty J, Baleux F, Oudar O. Glycosaminoglycan mimetics inhibit SDF-1/CXCL12-mediated migration and invasion of human hepatoma cells. Glycobiology. 2009;19:1511-1524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sutton A, Friand V, Papy-Garcia D, Dagouassat M, Martin L, Vassy R, Haddad O, Sainte-Catherine O, Kraemer M, Saffar L. Glycosaminoglycans and their synthetic mimetics inhibit RANTES-induced migration and invasion of human hepatoma cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:2948-2958. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kobayashi F, Yamada S, Taguwa S, Kataoka C, Naito S, Hama Y, Tani H, Matsuura Y, Sugahara K. Specific interaction of the envelope glycoproteins E1 and E2 with liver heparan sulfate involved in the tissue tropismatic infection by hepatitis C virus. Glycoconj J. 2012;29:211-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Dudás J, Bocsi J, Fullár A, Baghy K, Füle T, Kudaibergenova S, Kovalszky I. Heparin and liver heparan sulfate can rescue hepatoma cells from topotecan action. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:765794. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Richardson TP, Trinkaus-Randall V, Nugent MA. Regulation of heparan sulfate proteoglycan nuclear localization by fibronectin. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:1613-1623. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Stewart MD, Sanderson RD. Heparan sulfate in the nucleus and its control of cellular functions. Matrix Biol. 2014;35:56-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Beauvais DM, Rapraeger AC. Syndecans in tumor cell adhesion and signaling. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2004;2:3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Stanford KI, Bishop JR, Foley EM, Gonzales JC, Niesman IR, Witztum JL, Esko JD. Syndecan-1 is the primary heparan sulfate proteoglycan mediating hepatic clearance of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3236-3245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Conejo JR, Kleeff J, Koliopanos A, Matsuda K, Zhu ZW, Goecke H, Bicheng N, Zimmermann A, Korc M, Friess H. Syndecan-1 expression is up-regulated in pancreatic but not in other gastrointestinal cancers. Int J Cancer. 2000;88:12-20. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Matsumoto A, Ono M, Fujimoto Y, Gallo RL, Bernfield M, Kohgo Y. Reduced expression of syndecan-1 in human hepatocellular carcinoma with high metastatic potential. Int J Cancer. 1997;74:482-491. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Metwaly HA, Al-Gayyar MM, Eletreby S, Ebrahim MA, El-Shishtawy MM. Relevance of serum levels of interleukin-6 and syndecan-1 in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Sci Pharm. 2012;80:179-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Nault JC, Guyot E, Laguillier C, Chevret S, Ganne-Carrie N, N’Kontchou G, Beaugrand M, Seror O, Trinchet JC, Coelho J. Serum proteoglycans as prognostic biomarkers of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22:1343-1352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ramani VC, Purushothaman A, Stewart MD, Thompson CA, Vlodavsky I, Au JL, Sanderson RD. The heparanase/syndecan-1 axis in cancer: mechanisms and therapies. FEBS J. 2013;280:2294-2306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Filmus J, Capurro M, Rast J. Glypicans. Genome Biol. 2008;9:224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 407] [Cited by in RCA: 465] [Article Influence: 27.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Yan D, Lin X. Shaping morphogen gradients by proteoglycans. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a002493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 264] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Filmus J, Capurro M. The role of glypicans in Hedgehog signaling. Matrix Biol. 2014;35:248-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Yoneda A, Lendorf ME, Couchman JR, Multhaupt HA. Breast and ovarian cancers: a survey and possible roles for the cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans. J Histochem Cytochem. 2012;60:9-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Theocharis AD, Skandalis SS, Neill T, Multhaupt HA, Hubo M, Frey H, Gopal S, Gomes A, Afratis N, Lim HC. Insights into the key roles of proteoglycans in breast cancer biology and translational medicine. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1855:276-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Pilia G, Hughes-Benzie RM, MacKenzie A, Baybayan P, Chen EY, Huber R, Neri G, Cao A, Forabosco A, Schlessinger D. Mutations in GPC3, a glypican gene, cause the Simpson-Golabi-Behmel overgrowth syndrome. Nat Genet. 1996;12:241-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 591] [Cited by in RCA: 557] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Toretsky JA, Zitomersky NL, Eskenazi AE, Voigt RW, Strauch ED, Sun CC, Huber R, Meltzer SJ, Schlessinger D. Glypican-3 expression in Wilms tumor and hepatoblastoma. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2001;23:496-499. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Ota S, Hishinuma M, Yamauchi N, Goto A, Morikawa T, Fujimura T, Kitamura T, Kodama T, Aburatani H, Fukayama M. Oncofetal protein glypican-3 in testicular germ-cell tumor. Virchows Arch. 2006;449:308-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Nakatsura T, Kageshita T, Ito S, Wakamatsu K, Monji M, Ikuta Y, Senju S, Ono T, Nishimura Y. Identification of glypican-3 as a novel tumor marker for melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:6612-6621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Zhu ZW, Friess H, Wang L, Abou-Shady M, Zimmermann A, Lander AD, Korc M, Kleeff J, Büchler MW. Enhanced glypican-3 expression differentiates the majority of hepatocellular carcinomas from benign hepatic disorders. Gut. 2001;48:558-564. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Capurro M, Wanless IR, Sherman M, Deboer G, Shi W, Miyoshi E, Filmus J. Glypican-3: a novel serum and histochemical marker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:89-97. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Lin H, Huber R, Schlessinger D, Morin PJ. Frequent silencing of the GPC3 gene in ovarian cancer cell lines. Cancer Res. 1999;59:807-810. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Murthy SS, Shen T, De Rienzo A, Lee WC, Ferriola PC, Jhanwar SC, Mossman BT, Filmus J, Testa JR. Expression of GPC3, an X-linked recessive overgrowth gene, is silenced in malignant mesothelioma. Oncogene. 2000;19:410-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Xiang YY, Ladeda V, Filmus J. Glypican-3 expression is silenced in human breast cancer. Oncogene. 2001;20:7408-7412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Yan PS, Chen CM, Shi H, Rahmatpanah F, Wei SH, Caldwell CW, Huang TH. Dissecting complex epigenetic alterations in breast cancer using CpG island microarrays. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8375-8380. [PubMed] |

| 42. | Filmus J, Capurro M. The role of glypican-3 in the regulation of body size and cancer. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:2787-2790. [PubMed] |

| 43. | Capurro MI, Xiang YY, Lobe C, Filmus J. Glypican-3 promotes the growth of hepatocellular carcinoma by stimulating canonical Wnt signaling. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6245-6254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 349] [Cited by in RCA: 387] [Article Influence: 19.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Wu Y, Liu H, Weng H, Zhang X, Li P, Fan CL, Li B, Dong PL, Li L, Dooley S. Glypican-3 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition of hepatocellular carcinoma cells through ERK signaling pathway. Int J Oncol. 2015;46:1275-1285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Ho M, Kim H. Glypican-3: a new target for cancer immunotherapy. Eur J Cancer. 2011;47:333-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 180] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Wang XY, Degos F, Dubois S, Tessiore S, Allegretta M, Guttmann RD, Jothy S, Belghiti J, Bedossa P, Paradis V. Glypican-3 expression in hepatocellular tumors: diagnostic value for preneoplastic lesions and hepatocellular carcinomas. Hum Pathol. 2006;37:1435-1441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Libbrecht L, Severi T, Cassiman D, Vander Borght S, Pirenne J, Nevens F, Verslype C, van Pelt J, Roskams T. Glypican-3 expression distinguishes small hepatocellular carcinomas from cirrhosis, dysplastic nodules, and focal nodular hyperplasia-like nodules. Am J Surg Pathol. 2006;30:1405-1411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | International Consensus Group for Hepatocellular NeoplasiaThe International Consensus Group for Hepatocellular Neoplasia. Pathologic diagnosis of early hepatocellular carcinoma: a report of the international consensus group for hepatocellular neoplasia. Hepatology. 2009;49:658-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 610] [Cited by in RCA: 589] [Article Influence: 36.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 49. | Jain D. Tissue diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2014;4:S67-S73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Di Tommaso L, Franchi G, Park YN, Fiamengo B, Destro A, Morenghi E, Montorsi M, Torzilli G, Tommasini M, Terracciano L. Diagnostic value of HSP70, glypican 3, and glutamine synthetase in hepatocellular nodules in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;45:725-734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 312] [Cited by in RCA: 296] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Timek DT, Shi J, Liu H, Lin F. Arginase-1, HepPar-1, and Glypican-3 are the most effective panel of markers in distinguishing hepatocellular carcinoma from metastatic tumor on fine-needle aspiration specimens. Am J Clin Pathol. 2012;138:203-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Jin GZ, Dong H, Yu WL, Li Y, Lu XY, Yu H, Xian ZH, Dong W, Liu YK, Cong WM. A novel panel of biomarkers in distinction of small well-differentiated HCC from dysplastic nodules and outcome values. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Yao S, Zhang J, Chen H, Sheng Y, Zhang X, Liu Z, Zhang C. Diagnostic value of immunohistochemical staining of GP73, GPC3, DCP, CD34, CD31, and reticulin staining in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Histochem Cytochem. 2013;61:639-648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Di Tommaso L, Destro A, Seok JY, Balladore E, Terracciano L, Sangiovanni A, Iavarone M, Colombo M, Jang JJ, Yu E. The application of markers (HSP70 GPC3 and GS) in liver biopsies is useful for detection of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2009;50:746-754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 229] [Cited by in RCA: 223] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 55. | Traister A, Shi W, Filmus J. Mammalian Notum induces the release of glypicans and other GPI-anchored proteins from the cell surface. Biochem J. 2008;410:503-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Liu XF, Hu ZD, Liu XC, Cao Y, Ding CM, Hu CJ. Diagnostic accuracy of serum glypican-3 for hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Biochem. 2014;47:196-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Feng M, Ho M. Glypican-3 antibodies: a new therapeutic target for liver cancer. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:377-382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 58. | Bezakova G, Ruegg MA. New insights into the roles of agrin. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:295-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 259] [Cited by in RCA: 263] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Kim N, Stiegler AL, Cameron TO, Hallock PT, Gomez AM, Huang JH, Hubbard SR, Dustin ML, Burden SJ. Lrp4 is a receptor for Agrin and forms a complex with MuSK. Cell. 2008;135:334-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 564] [Cited by in RCA: 524] [Article Influence: 30.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Bányai L, Sonderegger P, Patthy L. Agrin binds BMP2, BMP4 and TGFbeta1. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Reist NE, Werle MJ, McMahan UJ. Agrin released by motor neurons induces the aggregation of acetylcholine receptors at neuromuscular junctions. Neuron. 1992;8:865-868. [PubMed] |

| 62. | Daniels MP. The role of agrin in synaptic development, plasticity and signaling in the central nervous system. Neurochem Int. 2012;61:848-853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Khan AA, Bose C, Yam LS, Soloski MJ, Rupp F. Physiological regulation of the immunological synapse by agrin. Science. 2001;292:1681-1686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Mazzon C, Anselmo A, Cibella J, Soldani C, Destro A, Kim N, Roncalli M, Burden SJ, Dustin ML, Sarukhan A. The critical role of agrin in the hematopoietic stem cell niche. Blood. 2011;118:2733-2742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Song J, Lokmic Z, Lämmermann T, Rolf J, Wu C, Zhang X, Hallmann R, Hannocks MJ, Horn N, Ruegg MA. Extracellular matrix of secondary lymphoid organs impacts on B-cell fate and survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:E2915-E2924. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Mazzon C, Anselmo A, Soldani C, Cibella J, Ploia C, Moalli F, Burden SJ, Dustin ML, Sarukhan A, Viola A. Agrin is required for survival and function of monocytic cells. Blood. 2012;119:5502-5511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Barber AJ, Lieth E. Agrin accumulates in the brain microvascular basal lamina during development of the blood-brain barrier. Dev Dyn. 1997;208:62-74. [PubMed] |

| 68. | Groffen AJ, Buskens CA, van Kuppevelt TH, Veerkamp JH, Monnens LA, van den Heuvel LP. Primary structure and high expression of human agrin in basement membranes of adult lung and kidney. Eur J Biochem. 1998;254:123-128. [PubMed] |

| 69. | Groffen AJ, Ruegg MA, Dijkman H, van de Velden TJ, Buskens CA, van den Born J, Assmann KJ, Monnens LA, Veerkamp JH, van den Heuvel LP. Agrin is a major heparan sulfate proteoglycan in the human glomerular basement membrane. J Histochem Cytochem. 1998;46:19-27. [PubMed] |

| 70. | Liebner S, Czupalla CJ, Wolburg H. Current concepts of blood-brain barrier development. Int J Dev Biol. 2011;55:467-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Didangelos A, Yin X, Mandal K, Baumert M, Jahangiri M, Mayr M. Proteomics characterization of extracellular space components in the human aorta. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:2048-2062. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Gesemann M, Brancaccio A, Schumacher B, Ruegg MA. Agrin is a high-affinity binding protein of dystroglycan in non-muscle tissue. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:600-605. [PubMed] |

| 73. | Tátrai P, Dudás J, Batmunkh E, Máthé M, Zalatnai A, Schaff Z, Ramadori G, Kovalszky I. Agrin, a novel basement membrane component in human and rat liver, accumulates in cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Lab Invest. 2006;86:1149-1160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Vestentoft PS. Development and molecular composition of the hepatic progenitor cell niche. Dan Med J. 2013;60:B4640. [PubMed] |

| 75. | Tátrai P, Somorácz A, Batmunkh E, Schirmacher P, Kiss A, Schaff Z, Nagy P, Kovalszky I. Agrin and CD34 immunohistochemistry for the discrimination of benign versus malignant hepatocellular lesions. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:874-885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Somorácz A, Tátrai P, Horváth G, Kiss A, Kupcsulik P, Kovalszky I, Schaff Z. Agrin immunohistochemistry facilitates the determination of primary versus metastatic origin of liver carcinomas. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:1310-1319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Chakraborty S, Lakshmanan M, Swa HL, Chen J, Zhang X, Ong YS, Loo LS, Akıncılar SC, Gunaratne J, Tergaonkar V. An oncogenic role of Agrin in regulating focal adhesion integrity in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Kawahara R, Granato DC, Carnielli CM, Cervigne NK, Oliveria CE, Rivera C, Yokoo S, Fonseca FP, Lopes M, Santos-Silva AR. Agrin and perlecan mediate tumorigenic processes in oral squamous cell carcinoma. PLoS One. 2014;9:e115004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Reine TM, Kusche-Gullberg M, Feta A, Jenssen T, Kolset SO. Heparan sulfate expression is affected by inflammatory stimuli in primary human endothelial cells. Glycoconj J. 2012;29:67-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Steiner E, Enzmann GU, Lyck R, Lin S, Rüegg MA, Kröger S, Engelhardt B. The heparan sulfate proteoglycan agrin contributes to barrier properties of mouse brain endothelial cells by stabilizing adherens junctions. Cell Tissue Res. 2014;358:465-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Gallai M, Kovalszky I, Knittel T, Neubauer K, Armbrust T, Ramadori G. Expression of extracellular matrix proteoglycans perlecan and decorin in carbon-tetrachloride-injured rat liver and in isolated liver cells. Am J Pathol. 1996;148:1463-1471. [PubMed] |

| 82. | Iozzo RV. Perlecan: a gem of a proteoglycan. Matrix Biol. 1994;14:203-208. [PubMed] |

| 83. | Vischer P, Feitsma K, Schön P, Völker W. Perlecan is responsible for thrombospondin 1 binding on the cell surface of cultured porcine endothelial cells. Eur J Cell Biol. 1997;73:332-343. [PubMed] |

| 84. | Whitelock JM, Melrose J, Iozzo RV. Diverse cell signaling events modulated by perlecan. Biochemistry. 2008;47:11174-11183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 221] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Iozzo RV, Sanderson RD. Proteoglycans in cancer biology, tumour microenvironment and angiogenesis. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15:1013-1031. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 421] [Cited by in RCA: 435] [Article Influence: 31.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Mongiat M, Sweeney SM, San Antonio JD, Fu J, Iozzo RV. Endorepellin, a novel inhibitor of angiogenesis derived from the C terminus of perlecan. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:4238-4249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 259] [Cited by in RCA: 263] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Bix G, Fu J, Gonzalez EM, Macro L, Barker A, Campbell S, Zutter MM, Santoro SA, Kim JK, Höök M. Endorepellin causes endothelial cell disassembly of actin cytoskeleton and focal adhesions through alpha2beta1 integrin. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:97-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Bix G, Iozzo RV. Novel interactions of perlecan: unraveling perlecan’s role in angiogenesis. Microsc Res Tech. 2008;71:339-348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Iozzo RV, Zoeller JJ, Nyström A. Basement membrane proteoglycans: modulators Par Excellence of cancer growth and angiogenesis. Mol Cells. 2009;27:503-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Seppinen L, Pihlajaniemi T. The multiple functions of collagen XVIII in development and disease. Matrix Biol. 2011;30:83-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Tátrai P, Kovalszky I. Proteoglycans in Chronic Liver Disease and Hepatocellular Carcinoma: An Update. Hepatocellular Carcinoma-Basic Research: InTech 2012; 171-200. |

| 92. | Musso O, Theret N, Heljasvaara R, Rehn M, Turlin B, Campion JP, Pihlajaniemi T, Clement B. Tumor hepatocytes and basement membrane-Producing cells specifically express two different forms of the endostatin precursor, collagen XVIII, in human liver cancers. Hepatology. 2001;33:868-876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Sun HC, Tang ZY. Angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma: the retrospectives and perspectives. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2004;130:307-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Musso O, Rehn M, Théret N, Turlin B, Bioulac-Sage P, Lotrian D, Campion JP, Pihlajaniemi T, Clément B. Tumor progression is associated with a significant decrease in the expression of the endostatin precursor collagen XVIII in human hepatocellular carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2001;61:45-49. [PubMed] |

| 95. | Quélard D, Lavergne E, Hendaoui I, Elamaa H, Tiirola U, Heljasvaara R, Pihlajaniemi T, Clément B, Musso O. A cryptic frizzled module in cell surface collagen 18 inhibits Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1878. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Folkman J. Antiangiogenesis in cancer therapy--endostatin and its mechanisms of action. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:594-607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 479] [Cited by in RCA: 467] [Article Influence: 23.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Sund M, Kalluri R. Tumor stroma derived biomarkers in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2009;28:177-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Szarvas T, László V, Vom Dorp F, Reis H, Szendröi A, Romics I, Tilki D, Rübben H, Ergün S. Serum endostatin levels correlate with enhanced extracellular matrix degradation and poor patients’ prognosis in bladder cancer. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:2922-2929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Sarrazin S, Adam E, Lyon M, Depontieu F, Motte V, Landolfi C, Lortat-Jacob H, Bechard D, Lassalle P, Delehedde M. Endocan or endothelial cell specific molecule-1 (ESM-1): a potential novel endothelial cell marker and a new target for cancer therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1765:25-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Delehedde M, Devenyns L, Maurage CA, Vivès RR. Endocan in cancers: a lesson from a circulating dermatan sulfate proteoglycan. Int J Cell Biol. 2013;2013:705027. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Huang GW, Tao YM, Ding X. Endocan expression correlated with poor survival in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:389-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | Ozaki K, Toshikuni N, George J, Minato T, Matsue Y, Arisawa T, Tsutsumi M. Serum endocan as a novel prognostic biomarker in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer. 2014;5:221-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 103. | Iozzo RV, Schaefer L. Proteoglycan form and function: A comprehensive nomenclature of proteoglycans. Matrix Biol. 2015;42:11-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 880] [Cited by in RCA: 856] [Article Influence: 85.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 104. | Korpetinou A, Skandalis SS, Labropoulou VT, Smirlaki G, Noulas A, Karamanos NK, Theocharis AD. Serglycin: at the crossroad of inflammation and malignancy. Front Oncol. 2014;3:327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | He L, Zhou X, Qu C, Tang Y, Zhang Q, Hong J. Serglycin (SRGN) overexpression predicts poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Med Oncol. 2013;30:707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 106. | Iozzo RV, Murdoch AD. Proteoglycans of the extracellular environment: clues from the gene and protein side offer novel perspectives in molecular diversity and function. FASEB J. 1996;10:598-614. [PubMed] |

| 107. | Schaefer L, Iozzo RV. Biological functions of the small leucine-rich proteoglycans: from genetics to signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:21305-21309. [PubMed] |

| 108. | Iozzo RV. The biology of the small leucine-rich proteoglycans. Functional network of interactive proteins. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18843-18846. [PubMed] |

| 109. | Kalamajski S, Oldberg A. The role of small leucine-rich proteoglycans in collagen fibrillogenesis. Matrix Biol. 2010;29:248-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 300] [Cited by in RCA: 338] [Article Influence: 22.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 110. | Iozzo RV. The family of the small leucine-rich proteoglycans: key regulators of matrix assembly and cellular growth. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1997;32:141-174. [PubMed] |

| 111. | Schönherr E, Hausser H, Beavan L, Kresse H. Decorin-type I collagen interaction. Presence of separate core protein-binding domains. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:8877-8883. [PubMed] |

| 112. | Villanueva A, Newell P, Chiang DY, Friedman SL, Llovet JM. Genomics and signaling pathways in hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 2007;27:55-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 421] [Cited by in RCA: 416] [Article Influence: 23.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 113. | Goldoni S, Humphries A, Nyström A, Sattar S, Owens RT, McQuillan DJ, Ireton K, Iozzo RV. Decorin is a novel antagonistic ligand of the Met receptor. J Cell Biol. 2009;185:743-754. [PubMed] |

| 114. | Iozzo RV, Buraschi S, Genua M, Xu SQ, Solomides CC, Peiper SC, Gomella LG, Owens RC, Morrione A. Decorin antagonizes IGF receptor I (IGF-IR) function by interfering with IGF-IR activity and attenuating downstream signaling. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:34712-34721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 115. | Schaefer L, Tsalastra W, Babelova A, Baliova M, Minnerup J, Sorokin L, Gröne HJ, Reinhardt DP, Pfeilschifter J, Iozzo RV. Decorin-mediated regulation of fibrillin-1 in the kidney involves the insulin-like growth factor-I receptor and Mammalian target of rapamycin. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:301-315. [PubMed] |

| 116. | Schönherr E, Sunderkötter C, Iozzo RV, Schaefer L. Decorin, a novel player in the insulin-like growth factor system. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:15767-15772. [PubMed] |

| 117. | Schaefer L, Iozzo RV. Small leucine-rich proteoglycans, at the crossroad of cancer growth and inflammation. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2012;22:56-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 118. | Seidler DG. The galactosaminoglycan-containing decorin and its impact on diseases. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2012;22:578-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 119. | Baghy K, Horváth Z, Regős E, Kiss K, Schaff Z, Iozzo RV, Kovalszky I. Decorin interferes with platelet-derived growth factor receptor signaling in experimental hepatocarcinogenesis. FEBS J. 2013;280:2150-2164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 120. | Buraschi S, Neill T, Owens RT, Iniguez LA, Purkins G, Vadigepalli R, Evans B, Schaefer L, Peiper SC, Wang ZX. Decorin protein core affects the global gene expression profile of the tumor microenvironment in a triple-negative orthotopic breast carcinoma xenograft model. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 121. | Morrione A, Neill T, Iozzo RV. Dichotomy of decorin activity on the insulin-like growth factor-I system. FEBS J. 2013;280:2138-2149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 122. | Zhu JX, Goldoni S, Bix G, Owens RT, McQuillan DJ, Reed CC, Iozzo RV. Decorin evokes protracted internalization and degradation of the epidermal growth factor receptor via caveolar endocytosis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:32468-32479. [PubMed] |

| 123. | Dudás J, Kovalszky I, Gallai M, Nagy JO, Schaff Z, Knittel T, Mehde M, Neubauer K, Szalay F, Ramadori G. Expression of decorin, transforming growth factor-beta 1, tissue inhibitor metalloproteinase 1 and 2, and type IV collagenases in chronic hepatitis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2001;115:725-735. [PubMed] |

| 124. | Yamaguchi Y, Mann DM, Ruoslahti E. Negative regulation of transforming growth factor-beta by the proteoglycan decorin. Nature. 1990;346:281-284. [PubMed] |

| 125. | Zhang Z, Li XJ, Liu Y, Zhang X, Li YY, Xu WS. Recombinant human decorin inhibits cell proliferation and downregulates TGF-beta1 production in hypertrophic scar fibroblasts. Burns. 2007;33:634-641. [PubMed] |

| 126. | Cabello-Verrugio C, Brandan E. A novel modulatory mechanism of transforming growth factor-beta signaling through decorin and LRP-1. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:18842-18850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 127. | Isaka Y, Brees DK, Ikegaya K, Kaneda Y, Imai E, Noble NA, Border WA. Gene therapy by skeletal muscle expression of decorin prevents fibrotic disease in rat kidney. Nat Med. 1996;2:418-423. [PubMed] |

| 128. | Shi YF, Zhang Q, Cheung PY, Shi L, Fong CC, Zhang Y, Tzang CH, Chan BP, Fong WF, Chun J. Effects of rhDecorin on TGF-beta1 induced human hepatic stellate cells LX-2 activation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1760:1587-1595. [PubMed] |

| 129. | Baghy K, Dezso K, László V, Fullár A, Péterfia B, Paku S, Nagy P, Schaff Z, Iozzo RV, Kovalszky I. Ablation of the decorin gene enhances experimental hepatic fibrosis and impairs hepatic healing in mice. Lab Invest. 2011;91:439-451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 130. | Breitkopf K, Haas S, Wiercinska E, Singer MV, Dooley S. Anti-TGF-beta strategies for the treatment of chronic liver disease. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:121S-131S. [PubMed] |

| 131. | Buraschi S, Pal N, Tyler-Rubinstein N, Owens RT, Neill T, Iozzo RV. Decorin antagonizes Met receptor activity and down-regulates {beta}-catenin and Myc levels. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:42075-42085. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 132. | Santra M, Mann DM, Mercer EW, Skorski T, Calabretta B, Iozzo RV. Ectopic expression of decorin protein core causes a generalized growth suppression in neoplastic cells of various histogenetic origin and requires endogenous p21, an inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinases. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:149-157. [PubMed] |

| 133. | Chung EJ, Sung YK, Farooq M, Kim Y, Im S, Tak WY, Hwang YJ, Kim YI, Han HS, Kim JC. Gene expression profile analysis in human hepatocellular carcinoma by cDNA microarray. Mol Cells. 2002;14:382-387. [PubMed] |

| 134. | Miyasaka Y, Enomoto N, Nagayama K, Izumi N, Marumo F, Watanabe M, Sato C. Analysis of differentially expressed genes in human hepatocellular carcinoma using suppression subtractive hybridization. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:228-234. [PubMed] |

| 135. | Shangguan JY, Dou KF, Li X, Hu XJ, Zhang FQ, Yong ZS, Ti ZY. [Effects and mechanism of decorin on the proliferation of HuH7 hepatoma carcinoma cells in vitro]. Xibao Yu Fenzi Mianyixue Zazhi. 2009;25:780-782. [PubMed] |

| 136. | Hamid AS, Li J, Wang Y, Wu X, Ali HA, Du Z, Bo L, Zhang Y, Zhang G. Recombinant human decorin upregulates p57KIP² expression in HepG2 hepatoma cell lines. Mol Med Rep. 2013;8:511-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 137. | Zhang Y, Wang Y, Du Z, Wang Q, Wu M, Wang X, Wang L, Cao L, Hamid AS, Zhang G. Recombinant human decorin suppresses liver HepG2 carcinoma cells by p21 upregulation. Onco Targets Ther. 2012;5:143-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 138. | Tralhão JG, Schaefer L, Micegova M, Evaristo C, Schönherr E, Kayal S, Veiga-Fernandes H, Danel C, Iozzo RV, Kresse H. In vivo selective and distant killing of cancer cells using adenovirus-mediated decorin gene transfer. FASEB J. 2003;17:464-466. [PubMed] |

| 139. | Horváth Z, Kovalszky I, Fullár A, Kiss K, Schaff Z, Iozzo RV, Baghy K. Decorin deficiency promotes hepatic carcinogenesis. Matrix Biol. 2014;35:194-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 140. | Meyer DH, Krull N, Dreher KL, Gressner AM. Biglycan and decorin gene expression in normal and fibrotic rat liver: cellular localization and regulatory factors. Hepatology. 1992;16:204-216. [PubMed] |

| 141. | Gressner AM, Krull N, Bachem MG. Regulation of proteoglycan expression in fibrotic liver and cultured fat-storing cells. Pathol Res Pract. 1994;190:864-882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 142. | Högemann B, Edel G, Schwarz K, Krech R, Kresse H. Expression of biglycan, decorin and proteoglycan-100/CSF-1 in normal and fibrotic human liver. Pathol Res Pract. 1997;193:747-751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |