Published online Jan 14, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i2.549

Peer-review started: April 23, 2014

First decision: May 29, 2014

Revised: June 13, 2014

Accepted: July 30, 2014

Article in press: July 30, 2014

Published online: January 14, 2015

Processing time: 270 Days and 7.9 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the clinicopathological features of mixed-type gastric cancer and their influence on prognosis of mixed-type stage I gastric cancer.

METHODS: We analyzed 446 patients who underwent curative gastrectomy for stage I gastric cancer between 1999 and 2009. The patients were divided into two groups: those with differentiated or undifferentiated cancer (non-mixed-type, n = 333) and those with a mixture of differentiated and undifferentiated cancers (mixed-type, n = 113).

RESULTS: The overall prevalence of mixed-type gastric cancer was 25.3% (113/446). Compared with patients with non-mixed-type gastric cancer, those with mixed-type gastric cancer tended to be older at onset (P = 0.1252) and have a higher incidence of lymph node metastasis (P = 0.1476). They also had significantly larger tumors (P < 0.0001), more aggressive lymphatic invasion (P = 0.0011), and deeper tumor invasion (P < 0.0001). In addition, they exhibited significantly worse overall survival rates than did patients with non-mixed-type gastric cancer (P = 0.0026). Furthermore, mixed-type gastric cancer was independently associated with a worse outcome in multivariate analysis [P = 0.0300, hazard ratio = 11.4 (1.265-102.7)].

CONCLUSION: Histological mixed-type of gastric cancer contributes to malignant outcomes and highlight its usefulness as a prognostic indicator in stage I gastric cancer.

Core tip: Little is known about the clinical outcome of the histological mixed-type gastric cancer, which consists of differentiated and undifferentiated components. We evaluated the clinicopathological features of this cancer and their influences on the prognosis of patients with mixed-type stage I gastric cancer.

- Citation: Komatsu S, Ichikawa D, Miyamae M, Shimizu H, Konishi H, Shiozaki A, Fujiwara H, Okamoto K, Kishimoto M, Otsuji E. Histological mixed-type as an independent prognostic factor in stage I gastric carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(2): 549-555

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i2/549.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i2.549

Gastric cancer presents a variety of histological types, each of which shows different features. It is well known that the histological type is defined as one of the crucial factors for endoscopic treatment and lymphadenectomy in the treatment guidelines[1,2] and chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer. In the early stage of gastric cancer, the histological type influences the extent of lymph node metastasis; the undifferentiated type, in particular, is one of the independent risk factors of lymph node metastasis[3-5]. In the advanced stage of gastric cancer, the histological type is an important factor that predicts prognosis, recurrence patterns, and chemosensitivity in patients[6-9]. Thus, the histological type of gastric cancer has been regarded as a crucial factor that may have a potentially useful role in determining treatment strategies.

However, gastric cancer tissues often present with histological heterogeneity; a cancer tissue does not always consist of a single histological type of tumor cell but sometimes consists of a mixture of several different types. Therefore, it is difficult for pathologists to diagnose accurately the histological differentiation state of the tissues of mixed-type gastric cancer due to the restricted tumor volume, even from several biopsy specimens. Moreover, there are some differences in the definitions of the histological type described by the 14th Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma (JCGC)[10] and the 7th tumour-node-metastasis (TNM) classification[11]. For example, mixed-type gastric cancer is classified based on the predominant component by the JCGC, whereas it is classified based on the weakest differentiated component by the TNM classification. Such differences in the definitions could give rise to disagreement about the recognition of the histological types, particularly of mixed-type gastric cancer.

In this study, therefore, we hypothesized that a mixture of differentiated and undifferentiated components itself might be associated with malignant clinical outcomes and poorer prognosis in patients undergoing curative gastrectomy for stage I gastric cancer. To verify this hypothesis, we evaluated prognosis relative to the extent of differentiated or undifferentiated components by comparing the clinicopathological features between two groups: the non-mixed-type, which consists of either differentiated or undifferentiated cancers; and the mixed-type, which is a mixture of differentiated and undifferentiated cancers. Our results suggest that the presence of mixed-type gastric cancer serves as an indicator of poor prognosis in patients with stage I disease and needs meticulous follow-up with clinical satisfaction.

Four hundred and forty-six patients with stage I gastric cancer diagnosed according to the criteria of the 14th JCGC[10] and the 7th TNM classification[11] were enrolled in this study. All patients underwent curative gastrectomy with radical lymphadenectomy in the Department of Digestive Surgery, Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine, Japan between 1999 and 2009. Patients who underwent chemotherapy prior to surgery, had multiple lesions of gastric cancer, or both were excluded from this study. Median follow-up time was 63.0 mo. All patients were examined in the outpatient clinic by blood tests for carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and carbohydrate antigen (CA)19-9 every 3-6 mo after surgery, and annual computed tomography (CT) scans.

The resected stomach was opened and then placed on a flat board with the mucosal side up and was fixed in 10% buffered formalin solution. After fixation, tumors in the resected stomach were generally sectioned on the maximum cross-sectional plane parallel to the lesser curvature line based on the rules of the JCGC[10]. Tumors were sectioned in their entirety parallel to the reference line at intervals of 5 mm. The resected specimens were embedded in paraffin, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. The clinicopathological features of these patients were obtained from hospital records based on the 14th JCGC[10] and the 7th TNM classification[11], excluding the definition of the histological type.

The histological types of resected tumor specimens were categorized into two major types: (1) expanding, intestinal or differentiated type; and (2) infiltrative, diffuse or undifferentiated type[12,13], based on the Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010[1]. These state that the differentiated cancer includes papillary and tubular adenocarcinomas, which arise from the gastric mucosa with intestinal metaplasia, whereas the undifferentiated cancer includes poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, signet ring cell carcinoma, and mucinous adenocarcinoma, which arise from ordinary gastric mucosa without intestinal metaplasia[14]. Quantitation of the relative extent of differentiated and undifferentiated components in resected specimens was determined by histological analysis by at least two pathologists in our hospital.

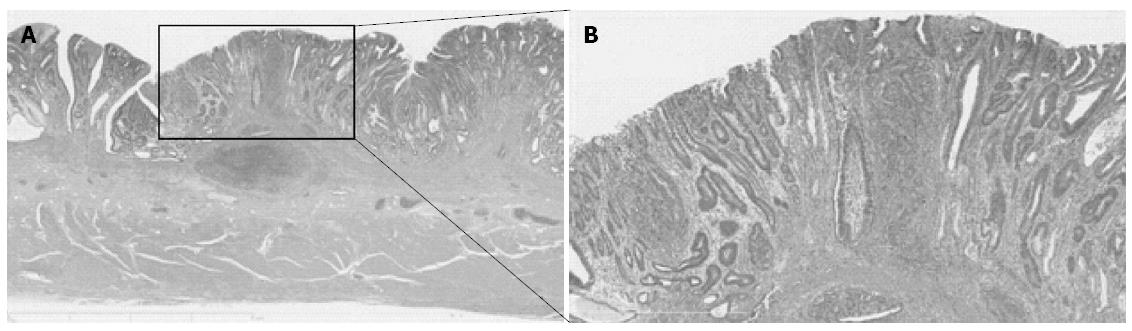

No universal standard has existed regarding the definition of the histological type, particularly in mixed-type gastric cancer. To define histological type according to both the JCGC and the TNM classification, all of the gastric cancers were divided into four subgroups: (1) a group that consisted solely of a differentiated component (pure D group); (2) a group that consisted predominantly of a differentiated component and has < 50% of an undifferentiated component (D > U group); (3) a group that consisted of > 50% of an undifferentiated component (U > D group); and (4) a group that consisted solely of an undifferentiated component (pure U group). According to the JCGC, the pure D and the D > U groups were classified as the differentiated type of gastric cancer, whereas the U > D and the pure U groups were classified as the undifferentiated type. On the other hand, according to the TNM classification, only the pure D group was classified as the differentiated type, and the remaining three groups as the undifferentiated type. Histological mixed-type gastric cancer consisted of both differentiated and undifferentiated components and belonged to the D > U or the U > D groups[15]. A representative case of mixed-type gastric cancer is shown in Figure 1.

The Fisher’s exact probability test and χ2 test were performed for categorical variables between two groups. Cause-specific death was recorded when death resulted from recurrent gastric cancer. The cumulative cause-specific overall survival rates were calculated by using the Kaplan-Meier method, and the log rank test was used to assess differences between clinical factors. Multivariate analysis using the Cox regression model was performed in order to identify significant contributors that were independently associated by univariate analysis. HRs are presented with 95%CIs. For all tests, P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

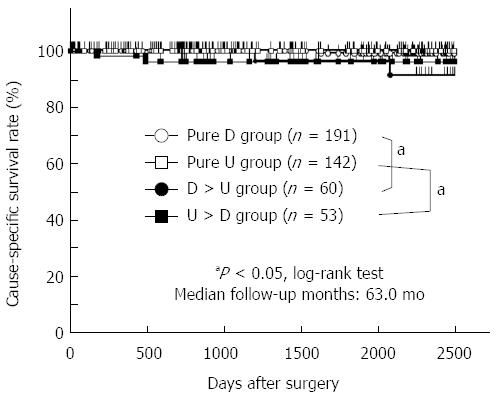

The four subgroups of histological differentiation state consisted of the pure D group of 191 patients (43%), the pure U group of 142 patients (32%), the D > U group of 60 patients (13%), and the U > D group of 53 patients (12%). According to the criteria of the JCGC, 251 of the 446 patients (56%) were diagnosed with differentiated gastric cancer (the pure D and the D > U groups), whereas 195 patients (44%) were diagnosed with undifferentiated gastric cancer (the U > D and the pure U groups). In contrast, according to the criteria of the TNM classification, 191 of the 446 patients (43%) were diagnosed with differentiated gastric cancer (the pure D group), whereas 255 patients (57%) were diagnosed with undifferentiated gastric cancer (the D > U, U > D, and pure U groups). Moreover, the histological mixed-type was made up of the D > U and the U > D groups of 113 patients (25%), and the non-mixed-type consisted of the pure D and the pure U groups of 333 patients (75%).

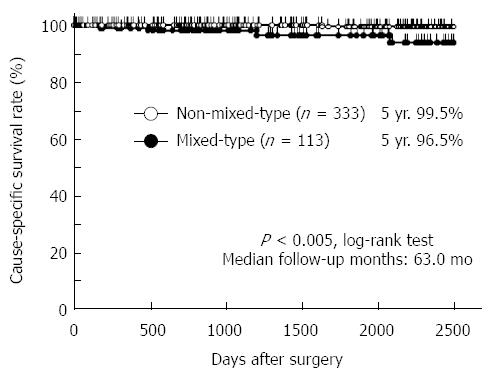

Cause-specific survival curves showed that the 5-year survival rates of patients in the pure D, pure U, D > U, and U > D groups were 99.0%, 100.0%, 96.3%, and 96.1%, respectively (Figure 2). There was no significant difference in the cause-specific survival rates between the differentiated and undifferentiated gastric cancer groups as defined by the JCGC (P = 0.7256) and the TNM classification (P = 0.3423). The prognosis of patients with mixed-type gastric cancer was significantly worse than that of patients with non-mixed-type gastric cancer (P = 0.0026) (Figure 3). These data implied that a mixture of differentiated and undifferentiated components was associated with poor prognosis of patients with gastric cancer. Indeed, in differentiated gastric cancer as defined by the JCGC, the prognosis of patients in the D > U group was significantly worse than that of patients in the pure D group (P = 0.0391) (Figure 2). Similarly, in undifferentiated gastric cancer as defined by the JCGC, the prognosis of patients in the U > D group was significantly worse than that of patients in the pure U group (P = 0.0231) (Figure 2). These findings strongly suggest that a mixture of these two components in each histological type could be related to poor prognosis in patients with stage I gastric cancer.

Clinicopathological factors were compared between the histological mixed-type and non-mixed-type of stage I gastric cancer (Table 1). Patients with the mixed-type cancer tended to be older at onset (P = 0.1252) and have a higher incidence of lymph node metastasis (P = 0.1476). They also had significantly larger tumors (P < 0.0001), more aggressive lymphatic invasion (P = 0.0011), and deeper tumor invasion (P < 0.0001).

| n | Histological type | P value | ||

| Mixed-type | Non-mixed-type | |||

| Sex | 446 | 113 | 333 | |

| Male | 305 | 76 (67) | 229 (69) | |

| Female | 141 | 37 (33) | 104 (31) | 0.7651 |

| Age (yr) | ||||

| < 65 | 233 | 52 (46) | 181 (54) | |

| ≥ 65 | 213 | 61 (54) | 152 (46) | 0.1252 |

| Location | ||||

| Upper | 340 | 81 (72) | 259 (78) | |

| Middle or Lower | 106 | 32 (28) | 74 (22) | 0.1883 |

| Histological type (JCGC) | ||||

| Differentiated | 251 | 60 (53) | 191 (57) | |

| Undifferentiated | 195 | 53 (47) | 142 (43) | 0.4302 |

| Macroscopic appearance (JCGC) | ||||

| Type 0 | 402 | 99 (88) | 303 (91) | |

| Type 1-5 | 44 | 14 (12) | 30 (9) | 0.2977 |

| Tumor size (mm) | ||||

| < 25 | 214 | 36 (32) | 178 (53) | |

| ≥ 25 | 232 | 77 (68) | 155 (47) | < 0.00011 |

| Venous invasion | ||||

| 0 | 410 | 102 (90) | 308 (92) | |

| 1-3 | 36 | 11 (10) | 25 (8) | 0.4526 |

| Lymphatic invasion | ||||

| 0 | 370 | 82 (73) | 288 (86) | |

| 1-3 | 76 | 31 (27) | 45 (14) | 0.00111 |

| TNM classification | ||||

| pT categories | ||||

| T1a | 11 | 34 (30) | 185 (56) | |

| T1b | 11 | 59 (52) | 124 (37) | |

| T2 | 31 | 20 (18) | 24 (7) | < 0.00011 |

| pN categories | ||||

| N0 | 427 | 105 (93) | 322 (97) | |

| N1 | 19 | 8 (7) | 11 (3) | 0.1476 |

Cause-specific survival rates of 446 patients with stage I gastric cancer were evaluated by univariate and multivariate analyses (Table 2). By univariate analysis, the presence of venous invasion (P < 0.0001) or histological mixed-type cancer (P = 0.0026) was considered as a significant prognostic factor. Multivariate analysis using Cox regression procedures revealed that the presence of mixed-type cancer was an independent factor that could predict a poor prognosis [P = 0.0300, HR = 11.4 (1.265-102.7)].

| Variables | Univariate1 | Multivariate2 | |||

| P value | HR | 95%CI | P value | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Male vs female | 0.5618 | ||||

| Age (yr) | |||||

| ≥ 65 vs < 65 | 0.1001 | ||||

| Location | |||||

| U vs ML | 0.8450 | ||||

| Histological type (JCGC) | |||||

| Undiff vs Diff | 0.7256 | ||||

| Tumor size (mm) | |||||

| ≥ 25 vs < 25 | 0.1918 | ||||

| Venous invasion | |||||

| Positive vs Negative | < 0.00013 | 13.513 | 2.252 | 83.33 | 0.00443 |

| Lymphatic invasion | |||||

| Positive vs Negative | 0.1796 | ||||

| pT-stage | |||||

| T2 vs T1 | 0.4781 | ||||

| pN-stage | |||||

| N1 vs N0 | 0.6373 | ||||

| Histological type | |||||

| Mixed vs Non-mixed | 0.00263 | 11.402 | 1.265 | 102.74 | 0.03003 |

Several studies have identified clinical features associated with the histological mixture of differentiated and undifferentiated components in gastric cancer[14-25]. However, the prognostic effects of these components in patients with gastric cancer remain little known, particularly in the early stages. In the present study, we demonstrated that the presence of histological mixed-type gastric cancer was associated with old-age onset, large tumor, deep tumor invasion, lymphatic invasion, and lymph node metastasis in stage I gastric cancer. Furthermore, mixed-type cancer was observed to be an independent prognostic factor in stage I gastric cancer. These results clearly suggest that patients with mixed-type stage I gastric cancer should receive more careful attention.

With respect to clinical outcomes of mixed-type gastric cancer, only a few studies have reported that mixed-type cancer is associated with lymph node metastasis[16,17,20] and larger tumors[18]. Regarding the prognostic effects of the differentiation state, we previously demonstrated that mixed-type cancer was associated with poor prognosis in differentiated T1/T2 cancer, as defined by the JCGC[15]. On the other hand, we did not clarify the relevance of this factor in undifferentiated cancer, as defined by the JCGC. In this study, however, we elucidated that the prognosis of patients in the U > D group was significantly worse than that of patients in the pure U group (P = 0.0231). Including other results, our data suggest that a mixture of histologically differentiated and undifferentiated components itself contributes to malignant clinical outcomes and poor prognosis of patients with gastric cancer, whether or not undifferentiated components predominate.

Consistent with our results, Huh et al[23] demonstrated the significance of the histological mixed-type in the undifferentiated type of early gastric cancer. Specifically, the histological mixed-type of signet ring cell carcinoma was one of the independent risk factors of lymph node metastasis, and patients with the mixed-type of this carcinoma showed significantly lower survival rates than those of patients with the non-mixed-type of the same carcinoma[23]. That study also supports our finding that the clinical aggressiveness of histological mixed-type components in undifferentiated gastric cancer is independent of the predominance of the undifferentiated component. Furthermore, from the viewpoint of molecular pathology, mixed-type gastric cancer exhibited increased expression of Ki-67, extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer, and vascular endothelial growth factor proteins, which are involved in angiogenesis and cell proliferation[24], and enhanced the status of CpG island hypermethylation in tumor suppressive genes[25]. These data also support the idea that the histological mixed-type gastric cancer is clinically aggressive. However, further studies are needed to validate the detailed mechanisms by which histological mixed-type gastric cancer is more aggressive than non-mixed-type gastric cancer.

The histological type has been defined as one of the factors that determine limited treatments according to Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines[1]. Consequently, endoscopic submucosal dissection with narrow-band imaging magnifying endoscopy[26] and limited gastrectomy with laparoscopic surgery[27,28] have emerged as new, less-invasive technologies, and are widely accepted as limited treatments for early gastric cancer. However, it is true that there might be some problems in using the classification of histological types in clinical settings, because it is difficult for pathologists to diagnose accurately the histological differentiation, particularly in the histological mixed-type gastric cancer, let alone to diagnose the histological differentiation in biopsy specimens. Therefore, in order to apply histological differentiation to clinical settings, whether the histological mixed-type or not itself may also be a better factor to determine limited treatments, as proposed by recent studies and our results[15-18,20]. Indeed, it is not so difficult for pathologists to diagnose whether tumor specimens are histological mixed-type gastric cancer or not.

In conclusion, this is believed to be the first report to demonstrate that histological mixed-type cancer is related to malignant outcomes and poor prognosis in the early stage of gastric cancer, and to highlight its usefulness as an indicator of poor prognosis. Therefore, for patients with mixed-type gastric cancer, meticulous follow-up should be performed after curative gastrectomy, even at the early stage of this disease.

Several studies have identified clinical features associated with the histological mixture of differentiated and undifferentiated components in gastric cancer. However, little is known about the prognostic effects of these components in patients with gastric cancer, particularly in the early stages.

This is believed to be the first report to demonstrate that histological mixed-type cancer is related to malignant outcomes and poor prognosis in the early stage of gastric cancer, and to highlight its usefulness as an indicator of poor prognosis. Therefore, for patients with mixed-type gastric cancer, meticulous follow-up should be performed after curative gastrectomy, even at the early stage of this disease.

Four hundred and forty-six patients, who underwent curative gastrectomy for stage I gastric cancer between 1999 and 2009, were enrolled in this study. The patients were divided into two groups: patients with either differentiated or undifferentiated cancer (non-mixed-type, n = 333) and patients with a mixture of differentiated and undifferentiated cancers (mixed-type, n = 113). The overall prevalence of mixed-type gastric cancer was 25.3% (113/446). Compared with patients with non-mixed-type gastric cancer, those with mixed-type gastric cancer tended to be older at onset (P = 0.1252) and have a higher incidence of lymph node metastasis (P = 0.1476). They also had significantly larger tumors (P < 0.0001), more aggressive lymphatic invasion (P = 0.0011), and deeper tumor invasion (P < 0.0001). In addition, they exhibited significantly worse overall survival rates than did patients with non-mixed-type gastric cancer (P = 0.0026). Furthermore, mixed-type gastric cancer was independently associated with a worse outcome in multivariate analysis [P = 0.0300, hazard ratio = 11.4 (1.265-102.7)].

These findings suggest that the histological mixed-type of gastric cancer contributes to malignant outcomes and highlight its usefulness as an indicator of poor prognosis in stage I gastric cancer.

Histological mixed-type gastric cancer: gastric cancer consists of both differentiated and undifferentiated components.

This was a good descriptive study showing that the presence of mixed-type gastric cancer serves as an indicator of poor prognosis in patients with stage I disease and requires meticulous follow-up with clinical satisfaction.

P- Reviewer: Leitman M S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Kerr C E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3). Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:113-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1723] [Cited by in RCA: 1895] [Article Influence: 135.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Nakajima T. Gastric cancer treatment guidelines in Japan. Gastric Cancer. 2002;5:1-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 410] [Cited by in RCA: 418] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Popiela T, Kulig J, Kolodziejczyk P, Sierzega M. Long-term results of surgery for early gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2002;89:1035-1042. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gotoda T, Sasako M, Ono H, Katai H, Sano T, Shimoda T. Evaluation of the necessity for gastrectomy with lymph node dissection for patients with submucosal invasive gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2001;88:444-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Folli S, Morgagni P, Roviello F, De Manzoni G, Marrelli D, Saragoni L, Di Leo A, Gaudio M, Nanni O, Carli A. Risk factors for lymph node metastases and their prognostic significance in early gastric cancer (EGC) for the Italian Research Group for Gastric Cancer (IRGGC). Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2001;31:495-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Adachi Y, Yasuda K, Inomata M, Sato K, Shiraishi N, Kitano S. Pathology and prognosis of gastric carcinoma: well versus poorly differentiated type. Cancer. 2000;89:1418-1424. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Noda S, Soejima K, Inokuchi K. Clinicopathological analysis of the intestinal type and diffuse type of gastric carcinoma. Jpn J Surg. 1980;10:277-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ribeiro MM, Sarmento JA, Sobrinho Simões MA, Bastos J. Prognostic significance of Lauren and Ming classifications and other pathologic parameters in gastric carcinoma. Cancer. 1981;47:780-784. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Maehara Y, Anai H, Kusumoto H, Sugimachi K. Poorly differentiated human gastric carcinoma is more sensitive to antitumor drugs than is well differentiated carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1987;13:203-206. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:101-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2390] [Cited by in RCA: 2865] [Article Influence: 204.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sobin L, Gospodarowicz M, Wittekind C, editors: International union against cancer. TNM classification of malignant tumours. 7th ed. New York: Wiley-Blackwell 2010; . |

| 12. | Nakamura K, Sugano H, Takagi K. Carcinoma of the stomach in incipient phase: its histogenesis and histological appearances. Gan. 1968;59:251-258. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Lauren P. The Two Histological Main Types Of Gastric Carcinoma: diffuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma. An attempt at a histo-clinical classification. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1965;64:31-49. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Tahara E, Semba S, Tahara H. Molecular biological observations in gastric cancer. Semin Oncol. 1996;23:307-315. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Shimizu H, Ichikawa D, Komatsu S, Okamoto K, Shiozaki A, Fujiwara H, Murayama Y, Kuriu Y, Ikoma H, Nakanishi M. The decision criterion of histological mixed type in “T1/T2” gastric carcinoma--comparison between TNM classification and Japanese Classification of Gastric Cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2012;105:800-804. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Watanabe G, Ajioka Y, Kato T. Pathological characteristics of differentiated-type early gastric carcinoma mixed with undifferentiated-type-Status of lymph node metastasis and macroscopic features [in Japanese with English abstract]. Stom Int. 2007;42:1577-1587. |

| 17. | Tanabe H, Iwashita A, Haraoka S. Clinicopathological characteristics of differentiated mixed-type early gastric carcinoma with lymph node metastasis [in Japanese with English abstract]. Stom Int. 2007;42:1561-1576. |

| 18. | Hanaoka N, Tanabe S, Mikami T, Okayasu I, Saigenji K. Mixed-histologic-type submucosal invasive gastric cancer as a risk factor for lymph node metastasis: feasibility of endoscopic submucosal dissection. Endoscopy. 2009;41:427-432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tajima Y, Murakami M, Yamazaki K, Masuda Y, Aoki S, Kato M, Sato A, Goto S, Otsuka K, Kato T. Risk factors for lymph node metastasis from gastric cancers with submucosal invasion. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1597-1604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Iwamoto J, Mizokami Y, Ito M, Shomokobe K, Hirayama T, Honda A, Saito Y, Ikegami T, Matsuzaki Y. Clinicopathological features of undifferentiated mixed type early gastric cancer treated with endoscopic submucosal dissection. Hepatogastroenterology. 2010;57:185-190. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Takao M, Kakushima N, Takizawa K, Tanaka M, Yamaguchi Y, Matsubayashi H, Kusafuka K, Ono H. Discrepancies in histologic diagnoses of early gastric cancer between biopsy and endoscopic mucosal resection specimens. Gastric Cancer. 2012;15:91-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Takizawa K, Ono H, Kakushima N, Tanaka M, Hasuike N, Matsubayashi H, Yamagichi Y, Bando E, Terashima M, Kusafuka K. Risk of lymph node metastases from intramucosal gastric cancer in relation to histological types: how to manage the mixed histological type for endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastric Cancer. 2013;16:531-536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Huh CW, Jung da H, Kim JH, Lee YC, Kim H, Kim H, Yoon SO, Youn YH, Park H, Lee SI. Signet ring cell mixed histology may show more aggressive behavior than other histologies in early gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2013;107:124-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zheng HC, Li XH, Hara T, Masuda S, Yang XH, Guan YF, Takano Y. Mixed-type gastric carcinomas exhibit more aggressive features and indicate the histogenesis of carcinomas. Virchows Arch. 2008;452:525-534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Park SY, Kook MC, Kim YW, Cho NY, Kim TY, Kang GH. Mixed-type gastric cancer and its association with high-frequency CpG island hypermethylation. Virchows Arch. 2010;456:625-633. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Nakayoshi T, Tajiri H, Matsuda K, Kaise M, Ikegami M, Sasaki H. Magnifying endoscopy combined with narrow band imaging system for early gastric cancer: correlation of vascular pattern with histopathology (including video). Endoscopy. 2004;36:1080-1084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 328] [Cited by in RCA: 335] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Huscher CG, Mingoli A, Sgarzini G, Sansonetti A, Di Paola M, Recher A, Ponzano C. Laparoscopic versus open subtotal gastrectomy for distal gastric cancer: five-year results of a randomized prospective trial. Ann Surg. 2005;241:232-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 650] [Cited by in RCA: 655] [Article Influence: 32.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Kitano S, Shiraishi N, Uyama I, Sugihara K, Tanigawa N. A multicenter study on oncologic outcome of laparoscopic gastrectomy for early cancer in Japan. Ann Surg. 2007;245:68-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 519] [Cited by in RCA: 518] [Article Influence: 28.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |