Published online May 21, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i19.6060

Peer-review started: December 1, 2014

First decision: January 8, 2015

Revised: January 24, 2015

Accepted: February 13, 2015

Article in press: February 13, 2015

Published online: May 21, 2015

Processing time: 176 Days and 14.5 Hours

This case report concerns a 25-year-old patient with 6-7 bloody stools/d, abdominal pain, tachycardia, and weight loss occurring during the third trimester of pregnancy. Severe ulcerative colitis complicated by toxic megacolon and gravidic sepsis was diagnosed by clinical evaluation, colonoscopy, and rectal biopsy that were performed safely without risk for the mother or baby. The patient underwent a cesarean section at 28+6 wk gestation. The baby was transferred to the neonatal intensive care unit of our hospital and survived without complications. Fulminant colitis was managed conservatively by combined colonoscopic decompression and medical treatment. Although current European guidelines describe toxic megacolon as an indication for emergency surgery for both pregnant and non-pregnant women, thanks to careful monitoring, endoscopic decompression, and intensive medical therapy with nutritional support, we prevented the woman from having to undergo emergency pancolectomy. Our report seems to suggest that conservative management may be a helpful tool in preventing pancolectomy if the patient’s condition improves quickly. Otherwise, surgery is mandatory.

Core tip: Severe ulcerative colitis complicated by toxic megacolon is widely considered to be an indication for emergency surgery. We reported a case of acute colitis in a healthy pregnant woman conservatively treated by intensive monitoring combined with medical therapy and endoscopic decompression in order to prevent the mother from having to undergo pancolectomy and the neonate from suffering an adverse perinatal outcome.

- Citation: Orabona R, Valcamonico A, Salemme M, Manenti S, Tiberio GA, Frusca T. Fulminant ulcerative colitis in a healthy pregnant woman. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(19): 6060-6064

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i19/6060.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i19.6060

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) which affects mainly young people in their reproductive period. A first disease attack of UC during pregnancy is uncommon, and is usually associated with an adverse outcome[1]. Antenatal disease progression correlates with activity at the onset of pregnancy: if UC is in remission at the time of conception, it will remain quiescent throughout pregnancy, while if it is active, it will progressively worsen, leading to an increased incidence of stillbirth, preterm delivery, or postpartum complications for both mother and neonate[2-6]. The management of UC during pregnancy is quite different from that in non-pregnant women because medical therapy, radiology, endoscopy, and surgery imply potential risks for the fetus[2,7]. This article describes an unusual case of UC which developed early in the third trimester of pregnancy and was managed by a multidisciplinary team.

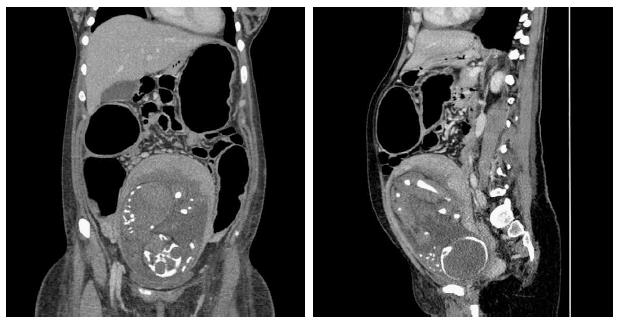

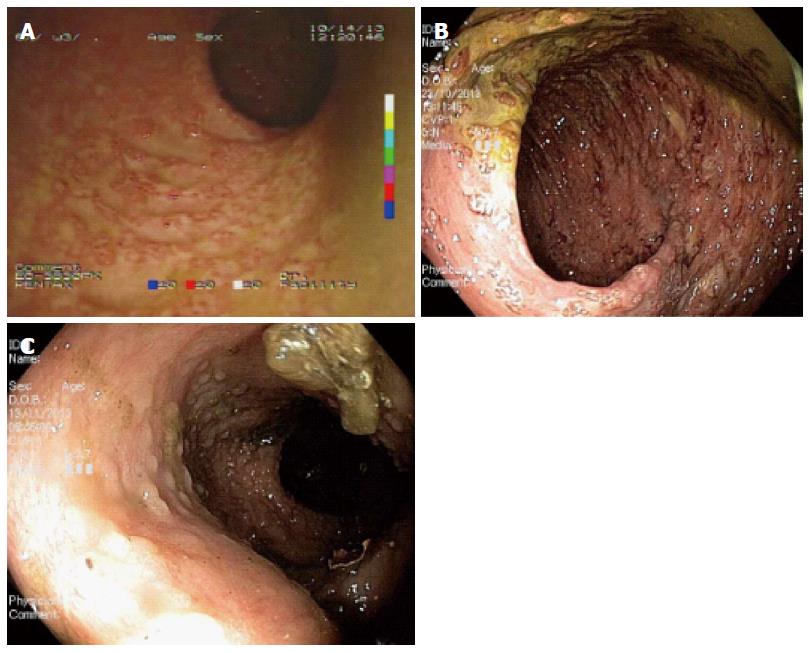

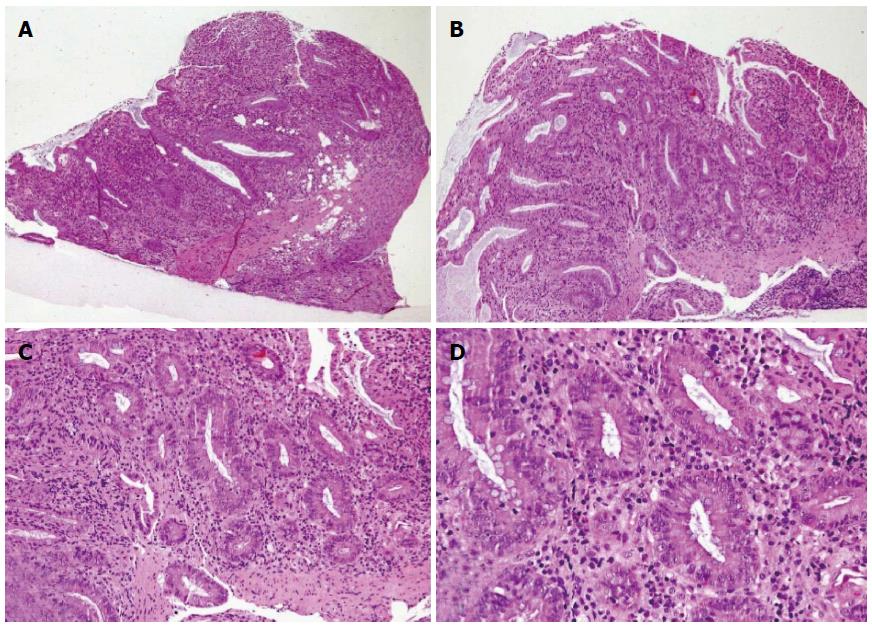

In October 2013 (1st October), a 25-year-old woman gravida 1/para 0 at 27 + 3 wk gestation without previous known diseases, presented to a periphery hospital with 6 episodes of bloody diarrhea per day for 6 d. Over the subsequent 3 d, she failed to improve and was transferred to the Obstetrics Department of the University Hospital of Brescia, Italy after a diagnosis of preterm labor (3rd October). At admission she had no fever and was tachycardic (105 bpm). Initial laboratory investigations included hemoglobin concentration (8.8 g/dL), C-reactive protein (CRP, 178 mg/L), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR, 45 mm/h). Obstetric ultrasound showed fetal cardiac activity appropriate for gestational age biometry and normal amniotic fluid index. Corticosteroids for the induction of fetal lung maturation were administered, together with tocolysis with atosiban and antibiotic therapy (clindamycin from 4th to 8th October, then imipenem). Microbiological testing for infectious diarrhea including Clostridium difficile toxin, Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., Campylobacter spp., Listeria monocytogenes, and Brucella melitensis was performed, were all negative. Meanwhile, because of the appearance of fever and a rise of inflammation indexes with worsening diarrhea (7-8 episodes of bloody stool per day), antibiotic therapy was switched to amikacin, vancomycin, metronidazole, and meropenem. The patient was non-responsive to antibiotics and her clinical condition continued to deteriorate. On 9th October, the patient’s bowels became closed to stool and gases. Computed tomography (Figure 1) revealed the presence of transverse colonic dilatation (9 cm), suggesting a diagnosis of toxic megacolon[8]. Hemocultures for aerobic and anaerobic bacteria were negative. Thereafter (10th October), the patient was transferred to the Intensive Care Unit with a diagnosis of severe sepsis (CRP 163 mg/L, procalcitonin 81.4 ng/mL). Serum albumin had fallen to 1.76 g/dL and albumin infusion was started. Endoscopic procedures were accurately planned in the surgery room and managed in conjunction with obstetricians and colorectal surgeons in order to eventually perform an emergency cesarean section (CS) and/or colectomy, if necessary. Presence of fetal heart activity was confirmed before sedation and after endoscopy. Colonoscopy showed complete substitution of the colorectal mucosa by a fibrinous layer (Figure 2). Ulcerative colitis was confirmed by histopathology (Figure 3). According to Truelove-Witts’ criteria, a diagnosis of a severe form of the disease was formulated[9]. The patient’s hemoglobin fell to 6.3 g/dL, and so she was given a blood transfusion. On 11th October (28 + 6 wk gestation), she underwent a CS. A male neonate was delivered weighing 1295 grams. He did not show any congenital anomalies. He was immediately intubated, transferred to the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) and survived without complications. Immediately after delivery, a colorectal surgeon performed a bowel evaluation and definitively excluded colectomy. On 14th October, intravenous methyl-prednisolone 60 mg/24 h (then oral prednisone 50 mg once a day) and oral mesalazine 500 mg three times a day (then 1600 mg three times a day) were started. Another colonoscopic decompression was performed and then the patient was transferred to the Gastroenterology Unit (16th October), where she underwent her third endoscopic decompression. Oral azathioprine was undertaken. Gastroscopy and magnetic resonance enterography excluded a form of overlap between Crohn’s disease and UC. Parenteral nutrition was stopped on 22nd November. The patient was discharged after 54 d of hospitalization, with follow-up being performed by the IBD Center of the Gastroenterology Unit. The baby was discharged five weeks later in good clinical condition.

On the basis of old reports and experiences, the course of UC during pregnancy correlates with the level of the disease activity at the time of conception. If conception occurs during a period of clinical remission, the disease will probably continue to be inactive throughout pregnancy[3,4]; while an active UC at conception will progressively worsen during pregnancy.

However, in our case report the patient presented with a first diagnosis of UC in the third trimester of pregnancy. The onset of IBD in a pregnant woman is uncommon and is usually associated with a poor prognosis[1,10] because of an increased overall risk of an adverse neonatal outcome; the most frequently described are preterm delivery and low birth weight[5,11-13].

An accurate patient history is crucial, as are clinical and pertinent investigations to assess colitis activity. Endoscopic evaluation and rectal biopsy play an essential role in the diagnosis, management, prognosis, and surveillance of antenatal IBD, and can be performed safely without a significant increase in complications for the mother or fetus[14].

Concerning the method of delivery, most studies have also shown a significantly increased incidence of CS, but it is not consistently clear whether this is predominantly due to elective or emergency CS[5,12,13]. Our decision to perform a CS was taken not only due to the extreme early gestational age, but also in order to evaluate with colorectal surgeons a balanced view of the bowel and possible surgical interventions.

UC management in pregnant women implies special considerations concerning risks for the fetus. For example, most drugs necessary in such cases (e.g., aminosalicylates agents and corticosteroids) are considered safe both for the mother and baby[2,14], but methotrexate and thalidomide are contraindicated[2]. Although there are limited data[15,16] on the safety of colonoscopy during pregnancy, it appears relatively safe, but requires several precautions concerning sedation and the left-sided position of the mother during the procedure, particularly in the third trimester. Obviously, it should be performed only when strongly indicated by an expert endoscopist after obstetric consultation[17]. In our case, the colonoscopy was performed not only for the diagnosis of UC complicated by toxic megacolon, but also to perform a colonoscopic decompression. Abdominal surgery, particularly when performed in the third trimester, is reported to increase the incidence of preterm labor and, consequently, implies a higher risk of adverse perinatal outcome[18]. According to guidelines, the indications for emergency surgery are the same for pregnant and non-pregnant women, including failed medical treatment[19] and complications such as toxic megacolon[2]. The principal advantages of a conservative management of toxic megacolon in pregnant women is to let the baby reach an appropriate gestational age to survive and, secondly, prevent the mother from having to undergo an emergency colectomy during gravidic sepsis. Although current guidelines describe toxic megacolon as an indication of emergency surgery[18], endoscopic decompression together with medical treatment and intensive monitoring should be a potentially successful management of severe UC complicated by toxic megacolon during pregnancy. Conversely, the presence of signs of acute abdomen, including perforation, abscess, ischemia, thrombosis (which were not present in our patient), and/or the lack of early response to conservative therapy, are indicators for surgery. Our report confirms the hypothesis that decisions regarding timing and indications for surgery are often challenging.

A 25-year-old woman gravida 1/para 0 with 6-7 bloody stools/d, abdominal pain, tachycardia, and weight loss occurring during the third trimester of pregnancy.

Bloody diarrhea, abdominal pain, hyporexia, apyrexy, and tachycardia.

Infectious colitis (Clostridium difficile, Cytomegalovirus, Salmonella spp., Shigella spp., Campylobacter spp., Listeria monocytogenes, and Brucella melitensis) and inflammatory bowel disease.

8.8 g/dL hemoglobin concentration, 178 mg/L C-reactive protein, 45 mm/h erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and 81.4 ng/mL procalcitonin.

CT scan showed an ascending colon diameter of 7.6 cm, a transverse colon of 9.2 cm, and a descending colon of 5.7 cm, which was consistent with toxic megacolon. Bowel wall thickness was normal without signs of ischemic sufferance. No abdominal free gas or effusion was detected.

Colonoscopy and biopsy revealed severe ulcerative colitis in the active phase.

The patient was treated with intravenous and oral corticosteroids, oral mesalazine, azathioprine, nutritional support, antibiotics, blood transfusion, potassium parenteral correction, and albumin infusion.

New onset of ulcerative colitis during pregnancy is uncommon and associated with a poor prognosis.

Although current guidelines describe toxic megacolon as an indication for emergency surgery, endoscopic decompression together with medical treatment and intensive monitoring should be lead to the potentially successful management of severe ulcerative colitis complicated by toxic megacolon during pregnancy.

This case report describes the onset of ulcerative colitis complicated by toxic megacolon in a 25-year-old pregnant patient. A cesarean section was performed and the colitis was managed conservatively.

P- Reviewer: Celentano V, Iizuka M, Suzuki H S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Rutherford A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Korelitz BI. Inflammatory bowel disease and pregnancy. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1998;27:213-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | van der Woude CJ, Kolacek S, Dotan I, Oresland T, Vermeire S, Munkholm P, Mahadevan U, Mackillop L, Dignass A. European evidenced-based consensus on reproduction in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:493-510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hanan IM. Inflammatory bowel disease in the pregnant woman. Compr Ther. 1998;24:409-414. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Nielsen OH, Andreasson B, Bondesen S, Jarnum S. Pregnancy in ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1983;18:735-742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Reddy D, Murphy SJ, Kane SV, Present DH, Kornbluth AA. Relapses of inflammatory bowel disease during pregnancy: in-hospital management and birth outcomes. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1203-1209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bortoli A, Saibeni S, Tatarella M, Prada A, Beretta L, Rivolta R, Politi P, Ravelli P, Imperiali G, Colombo E. Pregnancy before and after the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel diseases: retrospective case-control study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:542-549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Dignass A, Lindsay JO, Sturm A, Windsor A, Colombel JF, Allez M, D’Haens G, D’Hoore A, Mantzaris G, Novacek G. Second European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of ulcerative colitis part 2: current management. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6:991-1030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 728] [Cited by in RCA: 702] [Article Influence: 54.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gan SI, Beck PL. A new look at toxic megacolon: an update and review of incidence, etiology, pathogenesis, and management. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2363-2371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Truelove SC, Witts LJ. Cortisone in ulcerative colitis; final report on a therapeutic trial. Br Med J. 1955;2:1041-1048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1832] [Cited by in RCA: 1867] [Article Influence: 26.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Baiocco PJ, Korelitz BI. The influence of inflammatory bowel disease and its treatment on pregnancy and fetal outcome. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1984;6:211-216. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Bengtson MB, Solberg IC, Aamodt G, Jahnsen J, Moum B, Vatn MH. Relationships between inflammatory bowel disease and perinatal factors: both maternal and paternal disease are related to preterm birth of offspring. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:847-855. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bush MC, Patel S, Lapinski RH, Stone JL. Perinatal outcomes in inflammatory bowel disease. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2004;15:237-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mahadevan U, Sandborn WJ, Li DK, Hakimian S, Kane S, Corley DA. Pregnancy outcomes in women with inflammatory bowel disease: a large community-based study from Northern California. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1106-1112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 265] [Cited by in RCA: 264] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Loftus EV, Kane SV, Bjorkman D. Systematic review: short-term adverse effects of 5-aminosalicylic acid agents in the treatment of ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:179-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cappell MS, Colon VJ, Sidhom OA. A study at 10 medical centers of the safety and efficacy of 48 flexible sigmoidoscopies and 8 colonoscopies during pregnancy with follow-up of fetal outcome and with comparison to control groups. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:2353-2361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Quan WL, Chia CK, Yim HB. Safety of endoscopical procedures during pregnancy. Singapore Med J. 2006;47:525-528. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Cappell MS. Risks versus benefits of gastrointestinal endoscopy during pregnancy. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:610-634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Øresland T, Bemelman WA, Sampietro GM, Spinelli A, Windsor A, Ferrante M, Marteau P, Zmora O, Kotze PG, Espin-Basany E. European evidence based consensus on surgery for ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:4-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 286] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 24.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Watson WJ, Gaines TE. Third-trimester colectomy for severe ulcerative colitis. A case report. J Reprod Med. 1987;32:869-872. [PubMed] |