Published online May 21, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i19.5910

Peer-review started: October 16, 2014

First decision: December 2, 2014

Revised: December 31, 2014

Accepted: February 5, 2015

Article in press: February 5, 2015

Published online: May 21, 2015

Processing time: 218 Days and 0.2 Hours

AIM: To investigate the risk factors causing structural sequelae after anastomotic leakage in patients with mid to low rectal cancer.

METHODS: Prospectively collected data of consecutive subjects who had anastomotic leakage after surgical resection for rectal cancer from March 2006 to May 2013 at Korea University Anam Hospital were retrospectively analyzed. Two subgroup analyses were performed. The patients were initially divided into the sequelae (stricture, fistula, or sinus) and no sequelae groups and then divided into the permanent stoma (PS) and no PS groups. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to identify the risk factors of structural sequelae after anastomotic leakage.

RESULTS: Structural sequelae after anastomotic leakage were identified in 29 patients (39.7%). Multivariate analysis revealed that diversion ileostomy at the first operation increases the risk of structural sequelae [odds ratio (OR) = 6.741; P = 0.017]. Fourteen patients (17.7%) had permanent stoma during the follow-up period (median, 37 mo). Multivariate analysis showed that the tumor level from the dentate line was associated with the risk of permanent stoma (OR = 0.751; P = 0.045).

CONCLUSION: Diversion ileostomy at the first operation increased the risk of structural sequelae of the anastomosis, while lower tumor location was associated with the risk of permanent stoma in the management of anastomotic leakage.

Core tip: This study aimed to find the risk factors causing structural sequelae of anastomotic site after leakage in rectal cancer patients. Anastomotic leakage is one of the most challenging complications. Even after patients recover from the acute complication phase, they can suffer from its structural sequelae including stricture, fistula, sinus, or permanent stoma. No studies have evaluated the risk factors causing structural sequelae of anastomosis after leakage. Here we report our data about the fate of anastomotic leakage and the risk factors that should be considered after anastomotic leakage in patients with rectal cancer.

- Citation: Ji WB, Kwak JM, Kim J, Um JW, Kim SH. Risk factors causing structural sequelae after anastomotic leakage in mid to low rectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(19): 5910-5917

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i19/5910.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i19.5910

Despite technological advancements in surgical devices, methods, and perioperative management, anastomotic leakage (AL) after colorectal surgery remains a significant problem for patients and surgeons. AL can result in poor surgical, oncological, and functional outcomes. It increases postoperative morbidity and mortality[1,2] as well as local and systemic tumor recurrence or progression[3] and decreases quality of life[4-6]. Even with the proper management of AL, structural sequelae can develop such as prolonged fistula, sinus formation, or stricture. Those complications may cause various symptoms, complicate postoperative management, delay or prevent stomal repair, and postpone adjuvant treatment.

There have been many studies on AL after colorectal surgery as well as its risk factors[7-11]. However, none have examined the prognosis of leakage itself. Here we evaluated the clinical consequences of the anastomosis site after leakage and identified factors influencing poor anastomotic healing after leakage.

We performed a retrospective data analysis with prospectively collected data from a cohort of 107 consecutive patients who experienced AL after elective surgical resection for rectal cancer from March 2006 to May 2013 at Korea University Anam Hospital. A total of 809 patients with rectal cancer underwent surgical resection during this period. We included 79 patients in this study and excluded 28 patients who had upper rectal cancer (n = 16), were lost to follow-up, had postoperative mortalities (n = 9), or had another pelvic organ malignancy (n = 1). Follow-up loss was defined as when the patient did not present at the clinic on any of the designated dates during study period.

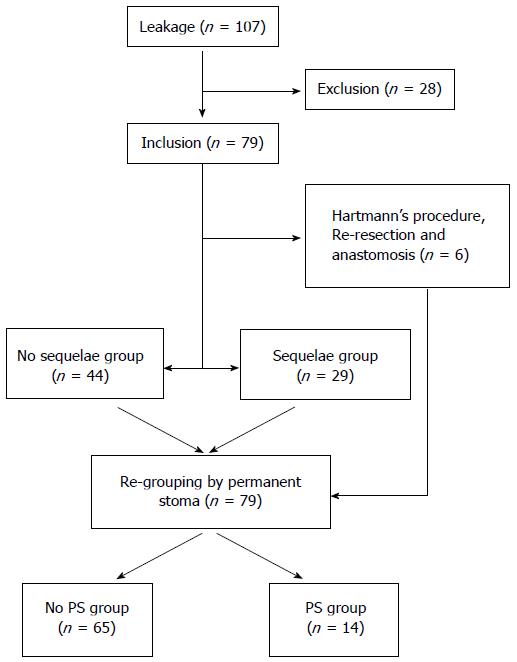

Two subgroup analyses were performed. First, all included patients were divided into the sequelae and no sequelae groups according to the existence of structural sequelae of AL (fistula, sinus, or stricture). Second, all patients were divided into the permanent stoma (PS) and no PS groups (Figure 1).

All surgical procedures were performed by three surgeons in a division that specialized in laparoscopic and robotic colorectal surgery. All surgical resections for rectal cancer were performed using a conventional laparoscopic or robotic method. A normal diet was resumed by clinical decision according to the surgeons’ preferences. The pathological examinations were performed by pathologists according to the seventh edition on colon and rectal cancer of the American Joint Committee on Cancer. The approach to managing AL was chosen by the surgeons among conservative management with antibiotic therapy, percutaneous abscess drainage (PAD), surgical procedures such as drainage and irrigation, diversion enterostomy with or without primary repair of the leakage site, re-resection with anastomosis, and Hartmann’s procedure.

After surgical resection of the rectal cancer, all patients were routinely followed every 3-6 mo during the first 2 years and every 6 mo thereafter. Routine follow-up tests included computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis, chest CT, and carcinoembryonic antigen levels. Total colonofiberoscopy or sigmoidoscopy was performed if needed. Patients with AL underwent additional CT, sigmoidoscopy, or contrast study at the physician’s discretion.

Anastomotic leakage was defined as in previous studies with any grade including abscess in close proximity and was diagnosed based on radiologic and endoscopic findings together with clinical signs such as a change in drainage color or signs of peritonitis that required surgery[12]. Mid to low rectal cancer was defined as rectal cancer located < 10 cm from the dentate line[13]. Hospital stay was defined as the period of time from admission until discharge. Intensive care unit (ICU) transfer was defined as transfer to the ICU during the course of in-hospital management including routine stays after the surgical procedure. Tumor location was defined as the length in centimeters between the lower tumor margin and the dentate line. Multi-organ failure was defined as functional deterioration of two or more vital organs.

Structural sequelae of AL included prolonged fistula, sinus formation, and anastomotic stricture. A fistula was diagnosed when the contrast study findings showed a fistulous tract connected to the intra-abdominal cavity, abdominal organ, or abscess cavity. Sinus formation was diagnosed when the end of a fistulous tract of any length without connection was identified during the examination. Anastomotic stricture was defined when the endoscopic findings showed any degree of stenotic lesion at the anastomotic area with or without symptoms. Permanent stoma was any type of enterostomy for the diversion that was not intended to be repaired until the last follow-up visit during the study period.

Continuous data were analyzed by Student’s t-test and categorical data were analyzed by logistic regression test or χ2 test with Fisher’s exact test as needed. Multivariate analysis was performed using a logistic regression test that was set up using univariate associations that were significant at P values < 0.05. Survival analysis and the test for cumulative incidence of permanent stoma were performed using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis with a log-rank test. All tests were two-sided and statistical significance was considered at P values < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics for Windows (version 20; IBM, Armonk, NY, United States).

The median follow-up period of the included 79 patients was 37 mo. Disease-related death occurred in five patients, while disease progression or recurrence was observed in 18 patients. The baseline characteristics of the included patients (n = 79) are presented in Table 1. There was no statistically significant difference in initial management methods after AL (Tables 2 and 3). A total of 29 patients underwent multiple invasive procedures to manage complications after the initial therapies. Conservative therapy using antibiotics and diet control was initially intended for 32 patients, but 11 of them (34.4%) underwent other management tactics such as PAD or surgical procedures.

| n (%) | Surgical method | n (%) | |

| Age (yr), median | 59 | ||

| Gender | Conventional | 3 (3.8) | |

| Male | 55 (69.6) | Laparoscopic | 45 (57.0) |

| Female | 24 (30.4) | Robotic | 28 (35.4) |

| BMI (mean, kg/m2) | 24.18 | Conversion | 3 (3.8) |

| ASA score | Anastomosis method | ||

| I | 34 (43.0) | Hand-sewn | 10 (12.8) |

| II | 43 (54.4) | Stapling | 68 (87.2) |

| III | 2 (2.5) | Anastomosis type | |

| Tumor stage | End-to-end | 70 (88.6) | |

| 0/I | 23 (29.1) | End-to-side | 5 (6.3) |

| II | 24 (30.4) | Colonic J-pouch | 4 (5.1) |

| III | 24 (30.4) | Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy | 19 (24.1) |

| IV | 8 (10.1) | Transfusion | 13 (17.3) |

| 95%CI | ||||||

| Sequelae1 | No sequelae | OR | Lower | Upper | P value | |

| Age, median (yr) | 62 | 55.5 | 0.037 | |||

| > 65 | 11 (37.9) | 14 (31.8) | 1.459 | 0.557 | 3.819 | 0.442 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 21 (72.4) | 30 (68.2) | 1.148 | 0.411 | 3.212 | 0.792 |

| BMI, mean | 23.99 | 24.25 | 0.748 | |||

| ASA score | ||||||

| I | 11 | 20 | ||||

| II/III | 18 | 24 | 1.259 | 0.487 | 3.255 | 0.635 |

| Operation time, mean (min) | 284.49 | 260.74 | 0.205 | |||

| Ileostomy | 21 (72.4) | 20 (45.5) | 3.412 | 1.254 | 9.290 | 0.016 |

| LNM, mean | 1.1 | 1.3 | 0.698 | |||

| RLN, mean | 22.1 | 23.6 | 0.681 | |||

| Stage | ||||||

| 0/I/II | 22 (75.9) | 22 (50.0) | ||||

| III/IV | 7 (24.1) | 22 (50.0) | 0.318 | 0.114 | 0.890 | 0.029 |

| Tumor location, median (centimeters from AV) | 5 | 5.5 | 0.144 | |||

| Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy | 9 (31.0) | 8 (18.2) | 2.137 | 0.715 | 6.393 | 0.174 |

| Surgical method | 0.080 | |||||

| Conventional | 0 | 3 (6.9) | ||||

| Laparoscopic | 14 (48.3) | 27 (61.4) | ||||

| Robotic | 13 (44.8) | 14 (31.8) | ||||

| Conversion | 2 (6.9) | 0 | ||||

| Anastomosis | 0.726 | |||||

| Hand-sewn | 3 (10.3) | 6 (13.6) | ||||

| Stapling | 26 (89.7) | 38 (86.4) | ||||

| Anastomosis type | 0.766 | |||||

| End-to-end | 26 (89.7) | 39 (88.6) | ||||

| End-to-side | 2 (6.9) | 2 (4.5) | ||||

| Colonic J-pouch | 1 (3.4) | 3 (6.9) | ||||

| Mechanical bowel preparation | ||||||

| Yes | 20 (69.0) | 34 (77.3) | ||||

| No | 9 (31.0) | 10 (22.7) | 0.784 | 0.281 | 2.187 | 0.642 |

| Initial AL management | 0.512 | |||||

| Conservative | 12 (41.4) | 20 (45.5) | ||||

| PAD | 7 (24.1) | 9 (20.5) | ||||

| Diversion only | 4 (13.8) | 10 (22.7) | ||||

| Primary repair + diversion | 0 | 1 (2.3) | ||||

| Surgical irrigation + drainage | 6 (20.7) | 4 (9.1) | ||||

| Transfusion | 8 (27.6) | 4 (9.1) | 3.810 | 1.027 | 14.137 | 0.046 |

| Leakage (d) | 5.7 | 4.2 | 0.054 | |||

| Hospital stay (d) | 48.9 | 20.9 | 0.001 | |||

| Days to start diet (d) | 6.3 | 5.7 | 0.665 | |||

| Antibiotics use (d) | 25.3 | 15.0 | 0.001 | |||

| ICU transfer | 3 (10.3) | 3 (6.9) | 1.212 | 0.251 | 5.852 | 0.811 |

| Multi-organ failure | 3 (10.3) | 2 (4.3) | 2.538 | 0.398 | 16.204 | 0.325 |

| Postoperative ileus | 5 (17.2) | 4 (8.7) | 2.197 | 0.536 | 8.935 | 0.276 |

| 95%CI | ||||||

| PS | No PS | OR | Lower | Upper | P value | |

| Age, median (yr) | 58 | 60 | 0.772 | |||

| > 65 | 4 (28.6) | 25 (38.5) | 0.250 | 0.181 | 2.262 | 0.488 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Male | 10 (71.4) | 45 (69.2) | 1.111 | 0.311 | 3.971 | 0.871 |

| BMI, mean | 24.29 | 24.16 | 0.893 | |||

| ASA score | ||||||

| I | 8 (57.1) | 26 (40.0) | ||||

| II/III | 6 (42.9) | 39 (60.0) | 0.500 | 0.155 | 1.609 | 0.245 |

| Surgical time, mean (min) | 274.79 | 269.63 | 0.827 | |||

| Ileostomy | 11 (78.6) | 34 (52.3) | 3.343 | 0.853 | 13.107 | 0.083 |

| LNM, mean | 2.21 | 1.06 | 0.299 | |||

| RLN, mean | 20.57 | 23.11 | 0.561 | |||

| Stage | ||||||

| 0/I/II | 9 (64.3) | 23 (58.5) | ||||

| III/IV | 5 (35.7) | 23 (41.5) | 0.782 | 0.236 | 2.594 | 0.688 |

| Tumor location, median (centimeters from AV) | 3 | 5 | 0.029 | |||

| Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy | 5 (35.7) | 14 (21.5) | 2.204 | 0.584 | 7.014 | 0.266 |

| Surgical method | 0.438 | |||||

| Conventional | 0 (0) | 3 (4.6) | ||||

| Laparoscopic | 10 (71.4) | 35 (53.8) | ||||

| Robotic | 3 (21.4) | 25 (38.5) | ||||

| Conversion | 1 (7.1) | 2 (3.1) | ||||

| Anastomosis | 0.545 | |||||

| Hand-sewn | 1 (7.7) | 9 (13.8) | ||||

| Stapling | 12 (92.3) | 56 (86.2) | ||||

| Anastomosis type | 0.129 | |||||

| End-to-end | 12 (85.7) | 58 (89.2) | ||||

| End-to-side | 2 (14.3) | 3 (4.6) | ||||

| Colonic J-pouch | 0 | 4 (6.2) | ||||

| Mechanical bowel preparation | ||||||

| Yes | 5 (35.7) | 17 (26.2) | ||||

| No | 9 (64.3) | 48 (73.8) | 0.638 | 0.187 | 2.171 | 0.471 |

| Initial AL management | 0.633 | |||||

| Conservative | 4 (28.6) | 29 (44.6) | ||||

| PAD | 4 (28.6) | 13 (20.0) | ||||

| Diversion only | 2 (14.3) | 12 (18.5) | ||||

| Primary repair and diversion | 0 | 1 (1.5) | ||||

| Surgical irrigation and drainage | 3 (21.4) | 7 (10.8) | ||||

| Re-anastomosis and diversion | 0 | 2 (3.1) | ||||

| Hartmann’s procedure | 1 (7.1) | 1 (1.5) | ||||

| Transfusion | 5 (35.7) | 10 (15.4) | 3.056 | 0.846 | 11.036 | 0.088 |

| Leakage, mean (d) | 5.0 | 4.7 | 0.768 | |||

| Hospital stay, mean (d) | 45.9 | 29.1 | 0.121 | |||

| Days to start diet, mean (d) | 7.5 | 5.8 | 0.427 | |||

| Antibiotics use, mean (d) | 26.8 | 17.5 | 0.018 | |||

| ICU transfer | 4 (28.6) | 5 (7.7) | 4.800 | 1.098 | 20.990 | 0.037 |

| Multi-organ failure | 3 (21.4) | 3 (4.6) | 5.636 | 1.005 | 31.602 | 0.049 |

| Postoperative ileus | 1 (7.1) | 8 (12.3) | 0.548 | 0.063 | 4.773 | 0.586 |

Among the 79 patients, six were excluded from this comparison because they experienced changes in the anastomosis site by Hartmann’s procedure or re-resection and anastomosis at any point during the management period. Structural sequelae after anastomotic leakage, such as prolonged fistula, sinus formation, and stricture, were identified in 29 patients (39.7%). Univariate analysis of the sequelae and no sequelae groups revealed that age, pathological stage (0/I/II), ileostomy, hospital stay, duration of antibiotic use, and transfusion were significantly different between the two groups (Table 4). Multivariate analysis performed using these variables showed that diversion ileostomy at the first operation increases the risk of complications [odds ratio (OR) = 6.741; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.404-32.364; P = 0.017; Table 4].

| 95%CI | ||||

| OR | Lower | Upper | P value | |

| Age | 1.035 | 0.979 | 1.095 | 0.378 |

| Ileostomy | 6.741 | 1.069 | 13.372 | 0.017 |

| Stage (III/IV) | 0.292 | 0.079 | 1.077 | 0.064 |

| Antibiotics use (d) | 1.016 | 0.954 | 1.085 | 0.613 |

| Hospital stay (d) | 1.045 | 0.987 | 1.106 | 0.135 |

| Transfusion | 5.760 | 0.787 | 42.138 | 0.085 |

Among 79 patients, 14 (17.7%) had a permanent enterostomy. None of the patients in the no sequelae group required a permanent stoma, while 15 patients (51.7%) in the sequelae group (n = 29) were able to have their stomas repaired after anastomotic complication management.

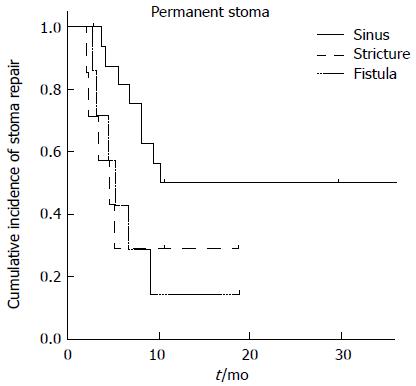

Sinus formation occurred in eight patients, stricture in nine, and fistula in 14. Of these, 87.5% of stomas with sinus formation and 66.7% of those with stricture were closed, but only 35.7% of stomas with prolonged fistula could be closed. A log-rank test revealed a difference in the risk of PS between AL complication types with borderline significance (P = 0.05; Figure 2).

There was a statistically significant difference between the PS and no PS group in terms of tumor location from the anal verge, duration of antibiotic use, ICU transfer, and multi-organ failure (Table 3). Multivariate analysis showed that a tumor location farther from the anal verge was associated with decreased risk of PS (OR = 0.751; 95%CI: 0.567-0.994; P = 0.045) (Table 5).

| 95%CI | ||||

| OR | Lower | Upper | P value | |

| Tumor location | 0.751 | 0.567 | 0.994 | 0.045 |

| Antibiotic use | 1.036 | 0.990 | 1.084 | 0.125 |

| ICU transfer | 4.184 | 0.277 | 63.162 | 0.301 |

| Multi-organ failure | 0.685 | 0.027 | 17.426 | 0.528 |

To our knowledge, this is the first study of the structural sequelae of AL to include its prognosis and risk factors. Although several studies have been performed to identify the factors influencing PS[14-16], we identified the risk of structural sequelae that can occur after leakage as well as the risk of having a PS of patients who underwent surgical resection for mid to low rectal cancer.

Temporary diversion with ileostomy is frequently performed after high-risk anastomosis. Several factors are associated with high-risk anastomosis including preoperative radiotherapy, male gender, low-level anastomosis, co-morbidities, steroid use, and obesity[9-11]. However, the decision to perform diversion ileostomy depends on the surgeon. Although ileostomy after rectal surgery could be considered a subjective variable, diversion turned out to be the single most predictive risk factor of structural sequelae of AL in the current study. Diversion after surgical resection of mid to low rectal cancer can be interpreted to indicate that the anastomosis was unstable for various reasons, including preoperative radiotherapy, difficult procedure due to a deep and narrow pelvis (as is common in male patients), or very a low-level anastomosis.

Diversion for protection against AL or a defunctioning stoma can reduce the risk of anastomosis failure[17,18]. In a randomized multicenter trial, Matthiessen et al[19] reported that a defunctioning stoma could reduce the risk of AL (OR = 3.4; P < 0.001). However, the results of our study showed that if AL had already occurred, diversion was the most predictive factor of structural sequelae of AL. The significant difference in hospital stay and duration of antibiotic use between the sequelae and no sequelae groups on univariate analysis is thought to reflect the association between the development of AL complications and its severity. In addition, transfusion is usually performed when the procedures are difficult for various reasons such as severe adhesion, narrow pelvis, and an advanced cancer lesion.

Dinnewitzer et al[16] reported that coloanal anastomosis and anastomotic leakage were risk factors for PS on multivariate analysis. den Dulk et al[20] reported that postoperative complications and secondary stoma formation were limiting factors for stoma reversal in patients undergoing total mesorectal excision (TME) for rectal cancer. We found that all protective diversions were repaired in patients who did not have structural sequelae of AL, whereas only 51.7% of patients in the sequelae group had repairable stomas. Our results also showed that a higher cancer lesion location decreased the risk of PS (OR = 0.751; P = 0.045). Univariate analysis showed that ICU transfer and multi-organ failure were associated with PS (Table 3). A patient’s postoperative condition might affect the decision to perform stoma repair.

The prognosis of patients who experience AL after colorectal surgery for colorectal cancer is known to be worse than that of those who do not[21-24]. We did not compare the leakage and non-leakage groups, but 5-year progression-free survival was significantly decreased in the patients who could not undergo stoma repair compared to those of patients who could (data now shown). Dekker et al[25] showed the importance of the first postoperative year for the prognosis of patients with colorectal cancer. Our finding of a worse 5-year progression-free survival rate of the PS group suggest that post-leakage structural sequelae should be a concern in the consideration of cancer prognosis.

We could not collect data on anorectal function for all of the included patients. Patients who had their stomas repaired might have problems with long-term anorectal function[26,27]. By adding functional data, we would learn more about the prognosis of structural sequelae of AL. Moreover, there were no standard protocols for the choice of management options for the structural sequelae of AL; rather, it depended on each physician’s choice[28-30]. Nonetheless, there was no statistically significant difference in management methods between the study groups (Tables 2 and 4).

In conclusion, even with proper management, patients undergoing rectal surgery may experience structural sequelae of anastomotic leakage. Although there are several reasons to perform diversion, our study showed that performing ileostomy significantly increased the risk of structural sequelae of AL and that a lower cancer lesion location was a risk factor for PS.

Anastomotic leakage is one of the significant complications experienced by patients with rectal cancer. However, even after proper management is provided for anastomotic leakage, patients my still develop structural sequelae of anastomotic leakage and the symptoms caused by them.

By retrospectively analyzing the data, the authors described the fate of anastomotic leakage and risk factors that cause the structural sequelae of anastomotic leakage.

In this study, the authors reviewed experience with anastomotic leakage in patients with mid to low rectal cancer to identify the risk factors of the structural sequelae of anastomotic leakage and permanent stoma. They concluded that previous diversion ileostomy was a risk factor of the structural sequelae of anastomotic leakage and a low cancer lesion location was a risk factor of permanent stoma.

P- Reviewer: Kornmann VNN S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Thornton M, Joshi H, Vimalachandran C, Heath R, Carter P, Gur U, Rooney P. Management and outcome of colorectal anastomotic leaks. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2011;26:313-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Platell C, Barwood N, Dorfmann G, Makin G. The incidence of anastomotic leaks in patients undergoing colorectal surgery. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9:71-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Walker KG, Bell SW, Rickard MJ, Mehanna D, Dent OF, Chapuis PH, Bokey EL. Anastomotic leakage is predictive of diminished survival after potentially curative resection for colorectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2004;240:255-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 333] [Cited by in RCA: 343] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Marinatou A, Theodoropoulos GE, Karanika S, Karantanos T, Siakavellas S, Spyropoulos BG, Toutouzas K, Zografos G. Do anastomotic leaks impair postoperative health-related quality of life after rectal cancer surgery? A case-matched study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57:158-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ashburn JH, Stocchi L, Kiran RP, Dietz DW, Remzi FH. Consequences of anastomotic leak after restorative proctectomy for cancer: effect on long-term function and quality of life. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:275-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Brown SR, Mathew R, Keding A, Marshall HC, Brown JM, Jayne DG. The impact of postoperative complications on long-term quality of life after curative colorectal cancer surgery. Ann Surg. 2014;259:916-923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kumar A, Daga R, Vijayaragavan P, Prakash A, Singh RK, Behari A, Kapoor VK, Saxena R. Anterior resection for rectal carcinoma - risk factors for anastomotic leaks and strictures. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1475-1479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Pommergaard HC, Gessler B, Burcharth J, Angenete E, Haglind E, Rosenberg J. Preoperative risk factors for anastomotic leakage after resection for colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Colorectal Dis. 2014;16:662-671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rullier E, Laurent C, Garrelon JL, Michel P, Saric J, Parneix M. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after resection of rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 1998;85:355-358. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Konishi T, Watanabe T, Kishimoto J, Nagawa H. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage after surgery for colorectal cancer: results of prospective surveillance. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;202:439-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 193] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Peeters KC, Tollenaar RA, Marijnen CA, Klein Kranenbarg E, Steup WH, Wiggers T, Rutten HJ, van de Velde CJ. Risk factors for anastomotic failure after total mesorectal excision of rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2005;92:211-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 492] [Cited by in RCA: 507] [Article Influence: 25.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Rahbari NN, Weitz J, Hohenberger W, Heald RJ, Moran B, Ulrich A, Holm T, Wong WD, Tiret E, Moriya Y. Definition and grading of anastomotic leakage following anterior resection of the rectum: a proposal by the International Study Group of Rectal Cancer. Surgery. 2010;147:339-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 732] [Cited by in RCA: 1029] [Article Influence: 68.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 13. | Zaheer S, Pemberton JH, Farouk R, Dozois RR, Wolff BG, Ilstrup D. Surgical treatment of adenocarcinoma of the rectum. Ann Surg. 1998;227:800-811. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Floodeen H, Lindgren R, Matthiessen P. When are defunctioning stomas in rectal cancer surgery really reversed? Results from a population-based single center experience. Scand J Surg. 2013;102:246-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Francone TD, Saleem A, Read TA, Roberts PL, Marcello PW, Schoetz DJ, Ricciardi R. Ultimate fate of the leaking intestinal anastomosis: does leak mean permanent stoma? J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:987-992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Dinnewitzer A, Jäger T, Nawara C, Buchner S, Wolfgang H, Öfner D. Cumulative incidence of permanent stoma after sphincter preserving low anterior resection of mid and low rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:1134-1142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Nurkin S, Kakarla VR, Ruiz DE, Cance WG, Tiszenkel HI. The role of faecal diversion in low rectal cancer: a review of 1791 patients having rectal resection with anastomosis for cancer, with and without a proximal stoma. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:e309-e316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Thoker M, Wani I, Parray FQ, Khan N, Mir SA, Thoker P. Role of diversion ileostomy in low rectal cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Surg. 2014;12:945-951. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Matthiessen P, Hallböök O, Rutegård J, Simert G, Sjödahl R. Defunctioning stoma reduces symptomatic anastomotic leakage after low anterior resection of the rectum for cancer: a randomized multicenter trial. Ann Surg. 2007;246:207-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 861] [Cited by in RCA: 795] [Article Influence: 44.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | den Dulk M, Smit M, Peeters KC, Kranenbarg EM, Rutten HJ, Wiggers T, Putter H, van de Velde CJ. A multivariate analysis of limiting factors for stoma reversal in patients with rectal cancer entered into the total mesorectal excision (TME) trial: a retrospective study. Lancet Oncol. 2007;8:297-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 233] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Alonso S, Pascual M, Salvans S, Mayol X, Mojal S, Gil MJ, Grande L, Pera M. Postoperative intra-abdominal infection and colorectal cancer recurrence: a prospective matched cohort study of inflammatory and angiogenic responses as mechanisms involved in this association. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41:208-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Salvans S, Mayol X, Alonso S, Messeguer R, Pascual M, Mojal S, Grande L, Pera M. Postoperative peritoneal infection enhances migration and invasion capacities of tumor cells in vitro: an insight into the association between anastomotic leak and recurrence after surgery for colorectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2014;260:939-943; discussion 943-944. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Krarup PM, Nordholm-Carstensen A, Jorgensen LN, Harling H. Anastomotic leak increases distant recurrence and long-term mortality after curative resection for colonic cancer: a nationwide cohort study. Ann Surg. 2014;259:930-938. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 18.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Mirnezami A, Mirnezami R, Chandrakumaran K, Sasapu K, Sagar P, Finan P. Increased local recurrence and reduced survival from colorectal cancer following anastomotic leak: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2011;253:890-899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 747] [Cited by in RCA: 680] [Article Influence: 48.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Dekker JW, van den Broek CB, Bastiaannet E, van de Geest LG, Tollenaar RA, Liefers GJ. Importance of the first postoperative year in the prognosis of elderly colorectal cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:1533-1539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lindgren R, Hallböök O, Rutegård J, Sjödahl R, Matthiessen P. Does a defunctioning stoma affect anorectal function after low rectal resection? Results of a randomized multicenter trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:747-752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Nesbakken A, Nygaard K, Lunde OC. Outcome and late functional results after anastomotic leakage following mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2001;88:400-404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 251] [Cited by in RCA: 257] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Basilico V, Griffa B, Radaelli F, Zanardo M, Rossi F, Caizzone A, Vannelli A. Anastomotic leakage following colorectal resection for cancer: how to define, manage and treat it. Minerva Chir. 2014;69:245-252. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Krarup PM, Jorgensen LN, Harling H. Management of anastomotic leakage in a nationwide cohort of colonic cancer patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;218:940-949. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Daams F, Luyer M, Lange JF. Colorectal anastomotic leakage: aspects of prevention, detection and treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:2293-2297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |