Published online Apr 14, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i14.4345

Peer-review started: July 17, 2014

First decision: August 15, 2014

Revised: September 4, 2014

Accepted: October 21, 2014

Article in press: October 21, 2014

Published online: April 14, 2015

Processing time: 272 Days and 2 Hours

AIM: To summarize the evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) regarding the effect of probiotics by using a meta-analytic approach.

METHODS: In July 2013, we searched PubMed, EMBASE, Ovid, the Cochrane Library, and three Chinese databases (Chinese Biomedical Literature Database, Chinese Medical Current Content, and Chinese Scientific Journals database) to identify relevant RCTs. We included RCTs investigating the effect of a combination of probiotics and standard therapy (probiotics group) with standard therapy alone (control group). Risk ratios (RRs) were used to measure the effect of probiotics plus standard therapy on Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication rates, adverse events, and patient compliance using a random-effect model.

RESULTS: We included data on 6997 participants from 45 RCTs, the overall eradication rates of the probiotic group and the control group were 82.31% and 72.08%, respectively. We noted that the use of probiotics plus standard therapy was associated with an increased eradication rate by per-protocol set analysis (RR = 1.11; 95%CI: 1.08-1.15; P < 0.001) or intention-to-treat analysis (RR = 1.13; 95%CI: 1.10-1.16; P < 0.001). Furthermore, the incidence of adverse events was 21.44% in the probiotics group and 36.27% in the control group, and it was found that the probiotics plus standard therapy significantly reduced the risk of adverse events (RR = 0.59; 95%CI: 0.48-0.71; P < 0.001), which demonstrated a favorable effect of probiotics in reducing adverse events associated with H. pylori eradication therapy. The specific reduction in adverse events ranged from 30% to 59%, and this reduction was statistically significant. Finally, probiotics plus standard therapy had little or no effect on patient compliance (RR = 0.98; 95%CI: 0.68-1.39; P = 0.889).

CONCLUSION: The use of probiotics plus standard therapy was associated with an increase in the H. pylori eradication rate, and a reduction in adverse events resulting from treatment in the general population. However, this therapy did not improve patient compliance.

Core tip: Probiotics have a positive effect on Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication since these compounds also induce anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative mechanisms that regulate intestinal microbiota. The benefits of probiotics supplementation in the treatment of antibiotic resistant H. pylori are still unclear due to the lack of supporting evidence. In this meta-analysis of 45 randomized controlled trials involving nearly 6997 individuals, we found that the use of probiotics plus standard therapy was associated with an increase in the H. pylori eradication rate, and a reduction in adverse events resulting from treatment in the general population. However, this therapy did not improve patient compliance.

-

Citation: Zhang MM, Qian W, Qin YY, He J, Zhou YH. Probiotics in

Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(14): 4345-4357 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i14/4345.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i14.4345

Since its identification in 1982 by Barry Marshall and Robin Warren, Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) has been studied for more than 30 years. The infection rate of this single dominant pathogen in the stomach varies between 1.2% and 95% according to age, geographic area, socioeconomic status, and other factors[1-5]. Infection with this organism results in a chronic effect by causing duodenal or gastric ulcers[6,7], gastric cancer[8,9], and gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid-tissue lymphoma[6,10]. The therapy used for the eradication of H. pylori also prevents the development of the diseases mentioned above in patients who are at high risk[8,11-13]. The success rate of standard therapy ranges from 60% to 90% using first-line treatment, and around 70% with second-line treatment[14-16]. Furthermore, the disruption of coevolved human and H. pylori genomes might play an important role in the high incidence of gastric disease[17,18]. Hence, the development of improved strategies is still under investigation to increase the efficiency of eradication or to increase patient compliance, which may contribute to a greater clinical value because of the prevalence of H. pylori infection in large populations[19]. Probiotics have a positive effect on H. pylori eradication since these compounds also induce anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative mechanisms that regulate intestinal microbiota[20-23].

Although several meta-analyses[24-27] have assessed the efficacy and safety of probiotics plus standard therapy, most of these studies have investigated these effects with respect to specific strains or certain formulations of probiotics[24-26]. Tong et al[27] demonstrated that the administration of probiotics can both improve the eradication rate and reduce adverse events, but their study did not examine the effect of probiotics on patient compliance. The benefits of probiotics supplementation in the treatment of antibiotic resistant H. pylori are still unclear due to the lack of supporting evidence[28]. In this study, we performed a meta-analysis of available randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to evaluate the effect of probiotics on H. pylori eradication, adverse events, and patient compliance.

This review was conducted and reported according to the requirements outlined in Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Statement, 2009 (Checklist S1)[29]. RCTs of probiotics plus standard therapy compared with standard therapy were included in our study, regardless of the publication status, i.e., published, in press, or in progress, and the effect of probiotic supplementation on H. pylori eradication, adverse events, and compliance were examined. Relevant trials were identified using the following procedure: (1) electronic searches: we searched PubMed, EMBASE, Ovid, The Cochrane Library, and three Chinese databases (Chinese Biomedical Literature Database, Chinese Medical Current Content, and Chinese Scientific Journals database) for articles published through July 2013. Both medical subject headings and free-language terms of H. pylori and probiotic, yeast, Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Streptococcus, Saccharomyces, Enterococcus, and Bacillus were used as search terms; and (2) other sources: meeting abstracts, references of meta-analyses or reviews already published on related topics, and the clinicaltrials.gov website were also screened for completed or on-going studies. Authors were contacted for essential information regarding publications that were not available in full. Medical subject headings, methods, patient population, interventions, and outcome variables of these studies were used to identify relevant trials.

The literature search, data extraction, and quality assessment were independently undertaken by 2 investigators (Qian W and Qin YY) using a standardized approach. Any inconsistencies between these investigators were identified by the primary investigator (Zhou YH) and resolved by consensus. We restricted our study to RCTs that were less likely to be subject to confounding variables or bias than observational studies.

A study was eligible for inclusion in our meta-analysis if the following criteria were met: (1) the study was a RCT; (2) the probiotics were administrated as adjuvant therapy in combination with the standard eradication therapy used for the treatment of H. pylori, including triple therapy, quadruple therapy and sequential therapy; (3) the probiotics group was treated with the standard eradication therapy plus probiotics and the control group received the same eradication regimens with or without a placebo; (4) the trial reported at least one of the following as an outcome: eradication rates, adverse events, or compliance; (5) if there were relevant studies with multiple arms, the data was combined to create a new study group and a new control group with reference to the criteria listed above; and (6) patient age or symptoms at the time of enrolment regardless of publication language were reported.

Finally, the exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) the study was not an RCT; (2) studies with only one group; and (3) studies in which patients were not treated with the standard therapy or in which the control group was treated differently from the group receiving the therapy.

All data from included trials were extracted independently by 2 investigators (Qian W and Qin YY) using a standardized protocol. Each data set was reviewed by a third investigator (Zhou YH), and any discrepancies between the 2 investigators’ data were resolved by discussion. The data collected from each study included characteristics of the enrolled patients, standard eradication therapy regimens, probiotic strains, dose and duration of probiotics, diagnostic methods of H. pylori infection, duration of the therapy and assessment, eradication rates, adverse events, and compliance. If the data of a study were published in more than one article, only the most recent publication was included. Both eradication rates by per-protocol set (PPS) analyses and intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses were collected.

The quality of the trials was assessed according to the recommendations of the Cochrane Collaboration[30], including random sequence generation (selection bias), allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding, intention-to-treat analysis, and completeness of follow-up. Judgments regarding the presence of methodological biases were determine by using the Cochrane criteria guidelines, Quality assessment was also performed independently by 2 researchers (Qian W and Qin YY), and was adjudicated by a third researcher (He J) when there were disagreements.

We computed the results of each RCT as dichotomous frequency data. Individual study risk ratios (RRs) and 95%CIs were calculated from event numbers extracted from each trial before data pooling. The overall RR and 95%CIs of eradication rates, adverse events, and compliance were also calculated. Both fixed-effect and random-effect models were used to assess the pooled RR for probiotics plus standard therapy compared with standard therapy. Results from the random-effects model were based on the assumption that the true underlying effect varied among the trials included in our meta-analysis presented here[31,32]. Heterogeneity of the treatment effects between studies was evaluated using the Q statistic, and we considered a P value < 0.10 to indicate significant heterogeneity[33,34].

Subgroup analyses were conducted for eradication rates by ITT analyses on the basis of the participant’s age (0-17 years as children; ≥ 18 years as adults; NM: the study was not mentioned or it contained both children and adults), single or multiple probiotic strains, high dose or low dose of probiotics (divided by the mean intake dosage per day of all included studies), duration of probiotics use longer than 15 d or not, duration of standard therapy longer than 7 d or not, duration between the end of the therapy and assessment longer than 4 wk or not, probiotic strains and types of standard therapy (first-line or second-line). Interaction tests[35] were performed to compare differences between the estimates of the 2 subsets, which were based on the Student t distribution rather than on a normal distribution because the number of inclusive studies was small. We also performed a sensitivity analysis by removing each individual trial from the meta-analysis[36]. Several methods were used to check for potential publication bias. Visual inspection of funnel plots for eradication rates, adverse events, and compliance were conducted. The Egger[37] and Begg test[38] were used to statistically assess publication bias for eradication rates, adverse events, and compliance. All reported P values were two-sided, and P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA software version 10.0 (Stata Corp., TX, United States).

Based on the literature search strategy, 4531 titles and abstracts were found from the 4 English databases; 102 of them were further searched based on abstracts or full articles, and 38 studies were enrolled. Another 7 studies from Chinese databases were enrolled later. Finally, 45 articles with 6997 participants were included[39-83] (PRISMA Flowchart). The characteristics of the 45 studies are listed in Table 1.

| Study | Patients (n) | Age (yr) | Methods of diagnosis | Methods of assessment | Probiotic regimens | Eradication therapy regimens and dosage (mg/d)1 |

| Navarro-Rodriguez et al[39], 2013 | 107 | Adults | UBT + HA + Giemsa + RUT | UBT + HA + Giemsa + RUT | Lacto + Bifido + Strep | 400F + 60La/60M + 1000Te |

| Ahmad et al[40], 2013 | 66 | Children | RUT/HA | HpSA | Lacto + Bifido + Strep | 3000A + 360F + 60M |

| Shavakhi et al[41],2013 | 180 | Adults | RUT/HA | UBT | Lacto + Bifido + Strep | 2000A + 480B + 1000C + 40M |

| Kyriakos et al[42], 2013 | 70 | Adults | RUT + HA | UBT | Saccha | 2000A + 1000C + 40M |

| Jiang et al[43], 20132 | 80 | Adults | RUT + Giemsa | UBT | Bacillus | 2000A + 60La + 3000Le |

| Dajani et al[44], 20132 | 301 | Both | UBT/RUT/HA/HpSA | UBT | Bifido | 2000A + 1000C/800Me + PPI |

| Deguchi et al[45], 2012 | 229 | Adults | Culture/(HA + RUT) | (UBT + HpSA) + Culture | Lacto | 1500A + 400C + 20R |

| Tolone et al[46], 2012 | 68 | Children | UBT + HA | UBT | Lacto + Bifido + Strep | 6000A + 1800C + 60M |

| Mirzaee et al[47], 20122 | 102 | Adults | UBT | UBT | NM | 2000A + 1000C + 40P |

| Manfredi et al[48], 20122 | 227 | Adults | RUT/HpSA | HpSA | Lacto + Bifido + Strep | 2000A + 1000C + 40E + 1000Ti |

| Du et al[49], 20122 | 234 | Adults | UBT/RUT/Giemsa | UBT | Lacto + Bacillus + Strep | 2000A + 1000C + 40M |

| Bekar et al[50], 2011 | 82 | Adults | UBT | UBT | Lacto + Bifido | 2000A + 1000C + 60La |

| Yoon et al[51], 2011 | 337 | NM | UBT/RUT/HA | UBT | Lacto + Bifido + Strep | 2000A + 1000C + 80E |

| He et al[52], 2011 | 84 | Adults | UBT + RUT | UBT + RUT | Lacto + Bifido + Entero | 2000A + 1000C + (40-60)R + 1000Ti |

| Xu et al[53], 2010 | 120 | NM | (UBT/RUT) + HA | UBT | Lacto + Bifido + Entero | 2000A + (20-40)E + 200F |

| Yaşar et al[54], 2010 | 76 | Adults | HA | UBT | Bifido | 2000A + 1000C + 80P |

| Wen et al[55], 2010 | 200 | NM | UBT + RUT | UBT | Lacto + Bifido + Entero | 2000A + 40P + 800Ti |

| Song et al[56], 20102 | 991 | Adults | RUT/HA | UBT | Saccha | 2000A + 1000C + 40M |

| Szajewska et al[57], 2009 | 83 | Children | 2 of (UBT, RUT, HA) | UBT | Lacto | 3000A + 1200C + 60M |

| Hurduc et al[58], 2009 | 90 | Children | RUT + HA | RUT + HA | Saccha | 3000A + 1800C + 60E/60M |

| Francavilla et al[59], 2008 | 40 | NM | 3 of (UBT, RUT, HA, HpSA) | UBT + HpSA | Lacto | 2000A + 1000C + 40R + 1000Ti (sequential) |

| Kim et al[60], 2008 | 347 | Adults | UBT/RUT/HA | UBT | Lacto + Bifido + Strep | 2000A + 1000C + PPI |

| Huang et al[61], 2008 | 120 | NM | UBT + RUT | UBT | Lacto + Bifido + Entero | 1000C + (20-40)E/(20-40)R + 1000Rn |

| Imase et al[62], 20082 | 19 | NM | NM | NM | Clost | 1500A + 800C + 60La |

| Cindoruk et al[63], 2007 | 124 | Adults | HA + Giemsa | UBT | Saccha | 2000A + 1000C + 60La |

| Park et al[64], 2007 | 352 | Adults | HA | UBT | Bacillus + Strep | 2000A + 1000C + 40M |

| de Bortoli et al[65], 2007 | 206 | NM | HA/(UBT + HpSA) | UBT | Lacto + Bifido + Strep | 2000A + 1000C + 40E |

| Sahagún-Flores et al[66], 2007 | 71 | Adults | HA | UBT | Lacto | 2000A + 1000C + 40M |

| Lionetti et al[67], 2006 | 40 | Children | 2 of (UBT, RUT, HA) | UBT | Lacto | 3000A + 900C + 60M + 1200Ti (sequential) |

| Goldman et al[68], 2006 | 65 | Children | UBT | UBT | Lacto + Bifido | 3000A + 900C + 60M |

| Sheu et al[69], 2006 | 138 | NM | UBT + HA | UBT | Lacto + Bifido + Strep | 2000A + 360B + 40M + 1000Me |

| Ziemniak et al[70], 20062 | 245 | Adults | UBT | UBT | Lacto | 2000A + 1000C + 80P |

| Sýkora et al[71], 2005 | 86 | Children | 2 of (RUT, HA, culture) + HpSA | UBT + HpSA | Lacto | 3000A + 900C + (1200-2400)M |

| Myllyluoma et al[72], 2005 | 47 | Adults | UBT + EIA | UBT | Lacto + Bifido + Propionibacterium | 2000A + 1000C + 60La |

| Duman et al[73], 2005 | 389 | NM | UBT + HA | NM | Saccha | 2000A + 1000C + 40M |

| Shimbo et al[74], 2005 | 35 | NM | RUT + Culture | UBT | Clost | 3000A + 800C + 120La |

| Cao et al[75], 2005 | 128 | NM | UBT + RUT | UBT + RUT | Lacto + Bifido + Entero | 2000A + 300B + 40M + 800Me |

| Nista et al[76], 2004 | 106 | Adults | UBT | UBT | Bacillus | 2000A + 1000C + 40R |

| Tursi et al[77], 2004 | 70 | NM | RUT + HA | UBT | Lacto | 3000A + 800B + 40E/40P + 1000Ti |

| Guo et al[78], 2004 | 97 | Adults | RUT + HA | UBT | Clost | 1000A + 200F + 40M |

| Sheu et al[79], 2002 | 160 | NM | (RUT/HA) + UBT | UBT/RUT/HA | Lacto + Bifido | 2000A + 1000C + 60La |

| Cremonini et al[80], 20022 | 85 | Adults | UBT | UBT | Lacto | 1000C + 40R + 1000Ti |

| Armuzzi et al[81], 2001a | 60 | Adults | UBT + EIA | UBT | Lacto | 1000C + 40R + 1000Ti |

| Armuzzi et al[82], 2001b | 120 | Adults | UBT + EIA | UBT | Lacto | 1000C + 80P + 1000Ti |

| Canducci et al[83], 2000 | 120 | NM | UBT + HA | UBT + HA | Lacto | 1500A + 750C + 40R |

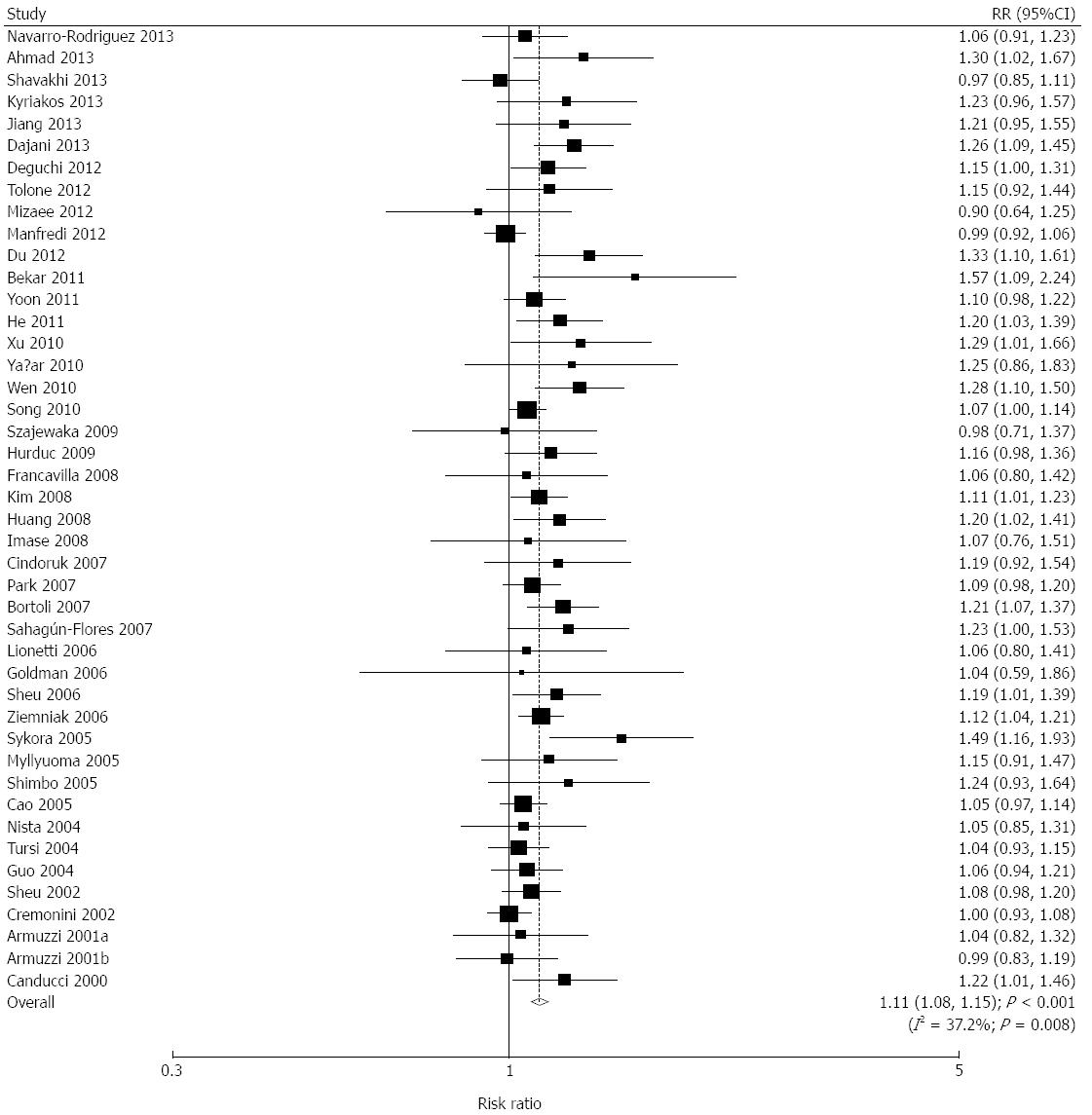

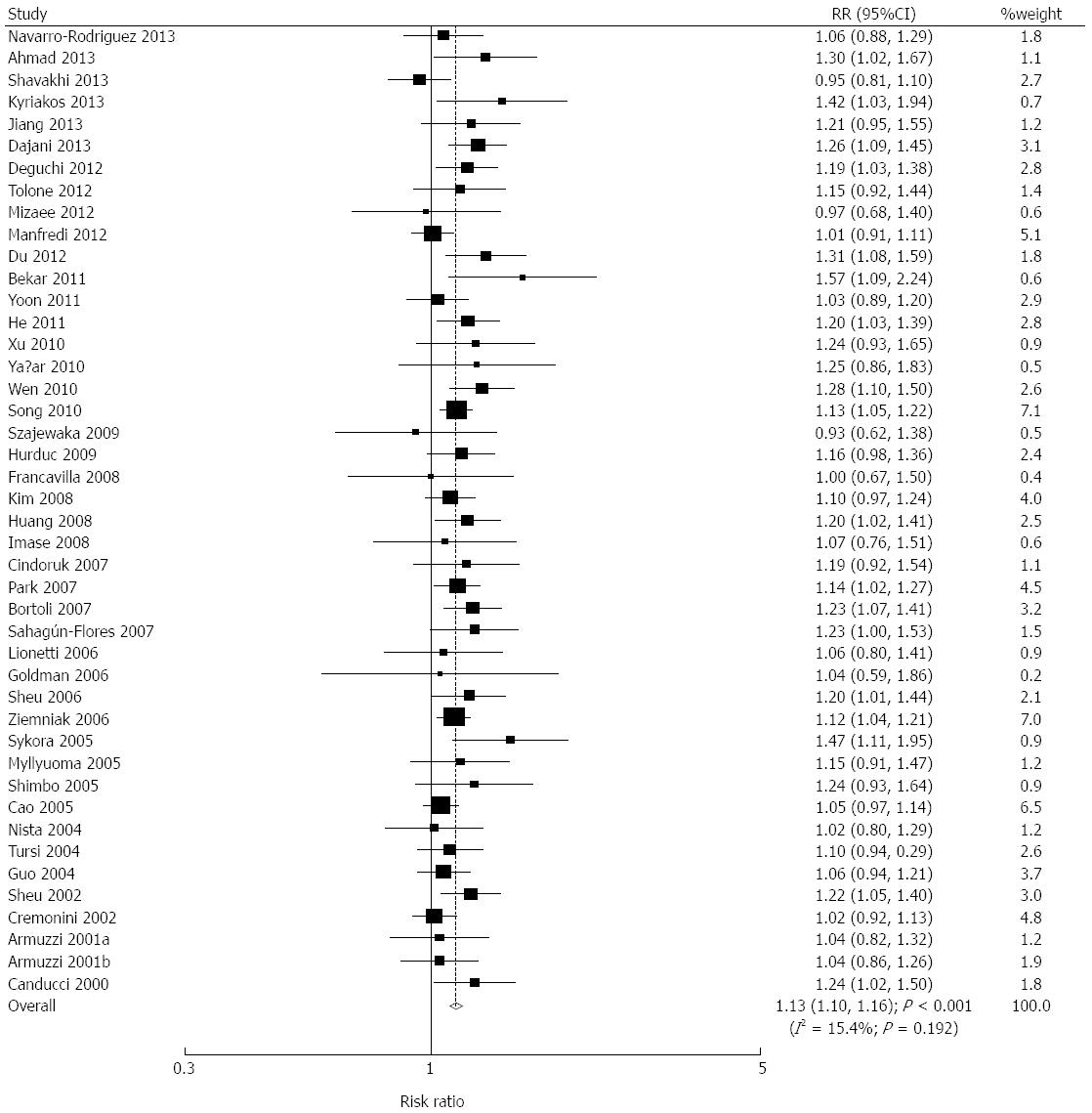

We acquired data relating to 6601 individuals to assess the effect of probiotics plus standard therapy on eradication rates. The pooled eradication rates for the probiotics group and the control group by PPS analysis were 86.23% and 76.60%, respectively. Overall, probiotics plus standard therapy significantly increased the eradication rates (RR = 1.11; 95%CI: 1.08-1.15; P < 0.001; Figure 1). Similarly, in ITT analysis, the pooled eradication rates for the probiotics group and the control group were 82.31% and 72.08%, respectively. Probiotics plus standard therapy significantly increased the eradication rates (RR = 1.13; 95%CI: 1.10-1.16; P < 0.001; Figure 2). Although there was significant heterogeneity across the trials by PPS analysis, a sensitivity analysis was conducted and the results suggested that the data were not affected by the sequential exclusion of any particular trial from the pooled analysis.

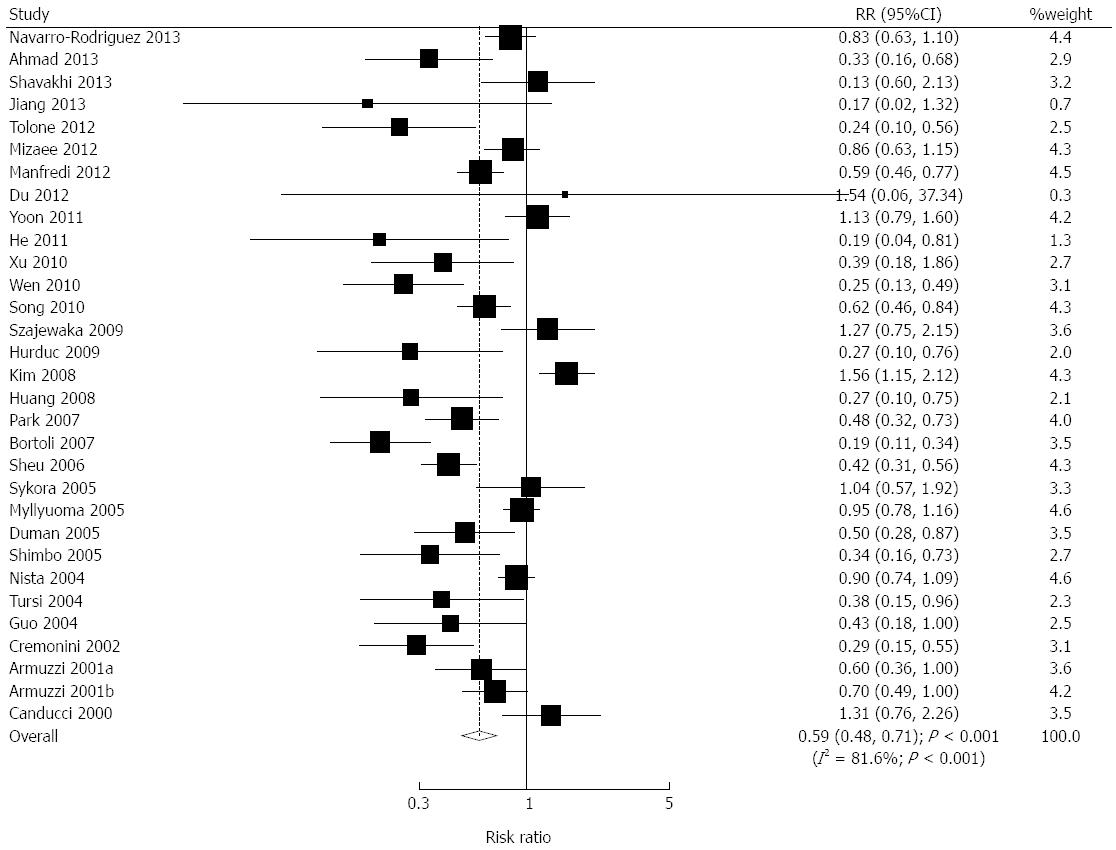

We acquired data on 5312 individuals to assess the effect of probiotics plus standard therapy on adverse events, and reported 1499 adverse events. We noted that probiotics plus standard therapy significantly reduced the risk of adverse events (RR = 0.59; 95%CI: 0.48-0.71; P < 0.001; Figure 3). Substantial heterogeneity was observed in the magnitude of the effect across the trials (I2 = 81.6%; P < 0.001). However, following sequential exclusion of each trial from the pooled analysis, we found that the outcome was not affected by the exclusion of any specific trial. The incidence rates were 21.44% and 36.27% in the probiotics group and the control group, respectively, which demonstrated a favorable effect of probiotics on the reduction of adverse events during H. pylori eradication therapy. As presented in Table 2, the combined effects of probiotics were statistically significant for all the listed adverse events, which clarified the protective effects of probiotics against these adverse events.

| Adverse Event | Trials (n) | Participants (n) | Probiotics group, % | Control group | RR and 95%CI | P value | Heterogeneity (P value) |

| Diarrhea | 26 | 4935 | 5.71% | 13.72% | 0.41 (0.30-0.57) | < 0.001 | 58% (P < 0.001) |

| Nausea/vomiting | 23 | 4067 | 6.95% | 12.83% | 0.60 (0.48-0.76) | < 0.001 | 23% (P = 0.16) |

| Epigastric discomfort | 8 | 1806 | 6.09% | 14.13% | 0.57 (0.44-0.74) | < 0.001 | 0% (P = 0.60) |

| Abdominal bloating | 13 | 1516 | 10.82% | 14.51% | 0.70 (0.55-0.90) | 0.005 | 0% (P = 0.53) |

| Abdominal pain | 10 | 1373 | 8.40% | 13.05% | 0.54 (0.35-0.83) | 0.005 | 31% (P = 0.16) |

| Constipation | 13 | 2021 | 3.96% | 6.73% | 0.55 (0.37-0.81) | 0.002 | 0% (P = 0.77) |

| Taste disturbance | 19 | 3611 | 11.79% | 18.76% | 0.63 (0.48-0.83) | < 0.001 | 73% (P < 0.001) |

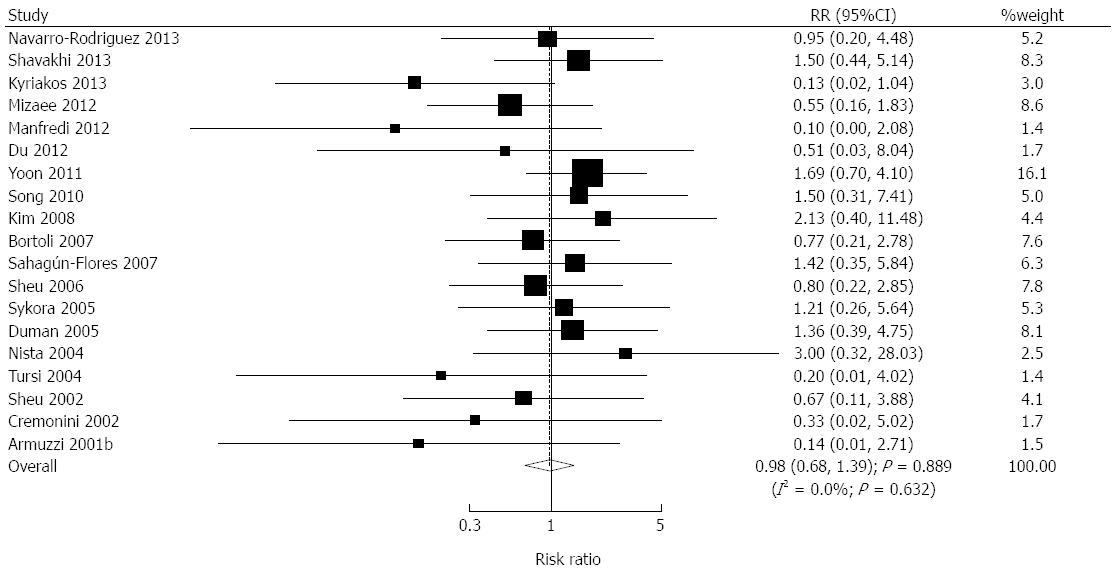

We acquired data on 4033 individuals to assess the effect of probiotics plus standard therapy on compliance, and reported 132 events of non-compliance. The inclusion of probiotics in the H. pylori eradication treatment regimen did not improve patient compliance according to the results of the pooled analysis (RR = 0.98; 95%CI: 0.68-1.39; P = 0.889; without evidence of heterogeneity; Figure 4).

The studies were divided into subgroups based on the age of the patients, single or multiple probiotic strains, dosage of probiotics, duration of probiotics intake, duration of standard eradication therapy, duration between the end of the therapy and assessment, probiotic strains and types of eradication therapy (Table 3). Overall, we noted that Clostridium had no significant effect on the eradication rate, and furthermore, probiotics did not affect the eradication rate if patients received a second-line standard therapy. Subgroup analyses based on other factors were associated with a statistically significant increase in the eradication rate.

| Subgroups | Studies (n) | Patients (n) | Probiotics group | Control group | RR and 95%CI | P value | P value for Q statistics |

| Age | |||||||

| Adults | 23 | 4116 | 81.86% | 73.23% | 1.12 (1.09-1.16) | < 0.001 | 0.224 |

| Children | 7 | 498 | 76.89% | 64.78% | 1.19 (1.07-1.32) | 0.002 | 0.535 |

| Probiotic strains | |||||||

| Multiple | 22 | 3598 | 83.29% | 73.73% | 1.12 (1.08-1.17) | < 0.001 | 0.046 |

| Single | 21 | 2908 | 81.60% | 70.60% | 1.16 (1.11-1.21) | < 0.001 | 0.724 |

| Dosage of probiotics (CFU/d) | |||||||

| ≥ 5 × 109 | 15 | 2470 | 82.84% | 73.06% | 1.13 (1.08-1.18) | < 0.001 | 0.571 |

| < 5 × 109 | 21 | 3283 | 81.49% | 70.69% | 1.14 (1.09-1.20) | < 0.001 | 0.046 |

| Duration of probiotic intake | |||||||

| ≥ 15 d | 17 | 3411 | 81.15% | 71.35% | 1.14 (1.10-1.18) | < 0.001 | 0.976 |

| < 15 d | 24 | 2585 | 82.30% | 71.28% | 1.12 (1.06-1.18) | < 0.001 | 0.022 |

| Duration of standard therapy | |||||||

| > 7 d | 17 | 2050 | 81.79% | 74.32% | 1.11 (1.06-1.17) | < 0.001 | 0.167 |

| = 7 d | 27 | 4558 | 82.39% | 70.97% | 1.16 (1.12-1.20) | < 0.001 | 0.502 |

| Duration between therapy ending and assessment | |||||||

| > 4 wk | 20 | 2520 | 83.86% | 73.36% | 1.16 (1.11-1.21) | < 0.001 | 0.282 |

| = 4 wk | 22 | 3984 | 80.78% | 70.91% | 1.14 (1.10-1.18) | < 0.001 | 0.358 |

| Probiotic (containing the following strains) | |||||||

| Lactobacillus | 31 | 4165 | 82.67% | 73.05% | 1.14 (1.10-1.18) | < 0.001 | 0.088 |

| Bifidobacterium | 20 | 3059 | 82.66% | 71.69% | 1.14 (1.10-1.19) | < 0.001 | 0.058 |

| Streptococcus | 11 | 2262 | 81.47% | 72.65% | 1.11 (1.06-1.17) | < 0.001 | 0.085 |

| Saccharomyces | 4 | 1275 | 81.14% | 69.94% | 1.15 (1.08-1.24) | < 0.001 | 0.594 |

| Bacillus | 4 | 772 | 80.71% | 69.74% | 1.17 (1.08-1.28) | < 0.001 | 0.408 |

| Enterococcus | 5 | 652 | 87.30% | 73.29% | 1.17 (1.06-1.30) | 0.003 | 0.046 |

| Clostridium | 3 | 151 | 93.06% | 86.08% | 1.08 (0.97-1.21) | 0.164 | 0.456 |

| Therapy regimens | |||||||

| First-line | 16 | 3474 | 81.02% | 71.00% | 1.13 (1.08-1.17) | < 0.001 | 0.260 |

| Second-line | 3 | 435 | 88.63% | 81.11% | 1.08 (1.00-1.17) | 0.058 | 0.185 |

| Not specified | 25 | 2699 | 82.67% | 72.25% | 1.18 (1.13-1.23) | < 0.001 | 0.268 |

A review of funnel plots did not exclude the potential for publication bias for the eradication rate, adverse events, and patient compliance. The Egger test[37] results showed potential publication bias for the eradication rate, adverse events, and patient compliance. The Begg test[38] results showed potential publication bias for patient compliance. The conclusions did not change after adjustment for publication bias by using the trim and fill method[84].

Through systematic review and meta-analysis using the results from 45 studies as solid supporting evidence, the effectiveness of the use of probiotics in H. pylori eradication therapy is based on 3 criteria: eradication rate, adverse events, and patient compliance. Our results suggest that additional probiotic supplementation significantly increases the eradication rate, and reduces adverse events. However, there is no significant effect on patient compliance.

The eradication rate of H. pylori using standard therapy plus probiotics has been significantly improved by about 13% compared with standard therapy alone. The value of RR is small because both the probiotics group and the control group have a relatively large eradication rate. Therefore, an improved eradication rate is the best indicator of the effectiveness of probiotics supplementation. Hence, the addition of probiotics to standard H. pylori eradication therapy improves the H. pylori eradication success rate within a population.

The duration of antibiotic treatment, different regimens of standard therapy, patient age, dosage of probiotics, different strains of probiotics[4,40,85-87], and different types of standard therapy have been reported to potentially influence the eradication outcome. In our study, there was a statistically significant increase in eradication rates in nearly all the subgroups when these factors were also taken into consideration. These subgroups showed similar outcomes with strong statistical significance, which may be influenced by a large sample size. We consider that probiotics had a comparable effect on the H. pylori eradication rate in all these subgroups of more than 500 patients. More studies are needed to assess the outcome in groups with fewer patients, such as groups of children and patients who received second-line therapy.

In addition to the subgroups mentioned above, antibiotic resistance can create a significant problem in H. pylori eradication therapy because it can become a major cause of initial eradication failure[19,88-90]. The prevalence of clarithromycin resistance cases treated with clarithromycin-containing triple therapy was reported to be 10%-30%[19,91]. With an increasing number of patients infected with clarithromycin and/or fluoroquinolone resistant H. pylori[92], quadruple therapy with bismuth colloid or sequential therapy has been suggested[92,93]. Probiotic supplementation in this population has rarely been studied before. In this meta-analysis, the studies focusing on antibiotic resistant H. pylori were far fewer than expected. Therefore, we have not included a thorough discussion on the topic of antibiotic-resistant strains here. The results from studies conducted so far seem promising and worth pursuing further through the initiation of studies using a larger population of patients.

In addition to improving the eradication rate of infectious organisms, the administration of probiotics can also reduce the incidence of adverse events by preventing or reducing pathogenic adherence, inducing the production of stomach acid, hydrogen peroxide, and bacteriocins to antagonize pathogen growth, and encourage the formation of normal balanced flora[68]. In our study, all the reported adverse events had RRs < 1, which indicated that the use of probiotics effectively protected the gut flora during H. pylori eradication. The overall incidence of adverse events was reduced by approximately 41% in the probiotics group. There are also studies confirming that the administration of probiotics can prevent diarrhea[94], abdominal bloating[95], and constipation[96-98].

Since probiotics are effective in the prevention of adverse events, they were also expected to promote patient compliance[22,28]. Non-compliance may drastically affect the H. pylori eradication success rate[2]; this aspect has seldom been studied. Manfredi et al[48] reported that the improvement in patient compliance in a study administering lactoferrin and probiotics to treat H. pylori infection was not statistically significant. Most studies had no dropouts or minimal losses to follow-up. The non-compliance rate was low and may relate to intrinsic personality traits, which can only be studied using a meta-analysis approach. Unexpectedly, there was no evidence showing a lower rate of non-compliance in the probiotics group. The RR showed a slight tendency for improved patient compliance, but this did not have any practical benefit on eradication success.

In clinical practice, the overall benefit of administering prophylactic probiotics to H. pylori-infected patients is not only related to the eradication success or reduced adverse events, but also to medical expenses; the influence of the latter factor in H. pylori eradication is still unclear. As H. pylori infection is more prevalent in developing countries or areas of lower socioeconomic status[4,99], the cost-effectiveness of taking probiotics may be subtle and difficult to evaluate. Tursi et al[77] reported that the extra cost of probiotics may be a limiting factor preventing widespread use. Some researchers report that probiotics were economical[100], but more evidence is required to support this statement.

This study may have the following limitations: (1) some publications may have been neglected to be added to the study because they were not included in any of the databases that were searched, leading to publication bias. Some publications that were unavailable were requested from the corresponding author in order to include their data in this study but only a few requests were answered; (2) there is a limited number of papers that include some subgroups, such as patients infected with antibiotic resistant H. pylori who were treated with probiotics. Analysis of these subgroups was not conducted; (3) there may be bias introduced by including studies with multiple arms, and routine means of measuring heterogeneity and publication bias; and (4) probiotics were analyzed by strains instead of by preparations that are available in clinical practice. Furthermore, the eradication therapies were divided into first-line or second-line therapies instead of into specific regimens to account for study number limitations. The correlation of probiotics and standard therapy was not included, and may contribute important information to this study.

In conclusion, the use of probiotics to supplement standard therapy in patients infected with H. pylori increased the eradication rate of the organism by about 13% and decreased the overall rate of adverse events by approximately 41%, independent of patient age, genera or dosage of probiotics, time of standard therapy or assessment, and therapy regimen. Unexpectedly, the patient compliance rate did not improve with the addition of probiotics to the therapeutic regimen. An economic evaluation is required to establish the cost-effectiveness of the addition of probiotics to H. pylori eradication therapy, and to determine whether the combination of probiotics with a standard therapy would be beneficial in clinical practice.

Certain studies have reported inconsistent results regarding the efficacy, safety and patient compliance of the use of probiotics in combination with a standard therapy when compared with standard therapy alone for the eradication of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori).

The benefits of probiotics supplementation in the treatment of antibiotic resistant H. pylori are still unclear due to the lack of supporting evidence. We therefore conducted a meta-analysis to summarize the evidence from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) regarding the effect of probiotics by using a meta-analytic approach.

Several meta-analyses have assessed the efficacy and safety of probiotics plus standard therapy, and most of these studies have investigated these effects with respect to specific strains or certain formulations of probiotics. In this study, we performed a meta-analysis of available RCTs to evaluate the effect of probiotics on H. pylori eradication, adverse events, and patient compliance.

Probiotics supplementing standard therapy in patients infected with H. pylori increased the eradication rate and decreased the overall rate of adverse events, independent of patient age, genera or dosage of probiotics, time of standard therapy or assessment, and therapy regimen. This study may represent a future strategy in the treatment of patients with H. pylori infection.

In this meta-analysis the articles chosen are sufficient by number and the distribution is worldwide. Addition of probiotics may be an option for low eradication regions. Effect of these live but nonpathogenic bacteria on eradication therapy of H. pylori may be by reducing antibiotic related side effects and/or possible antibacterial properties. The studies relating yo cost-effectiveness of this supplementation should be assessed before clinical usage. Also some other measures increasing the compliance of the patient should be taken into account, as appropriate region-based regimens informing the patient.

P- Reviewer: Ji JS, Kanda T, Ulasoglu C S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: Cant MR E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Bik EM, Eckburg PB, Gill SR, Nelson KE, Purdom EA, Francois F, Perez-Perez G, Blaser MJ, Relman DA. Molecular analysis of the bacterial microbiota in the human stomach. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:732-737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 730] [Cited by in RCA: 780] [Article Influence: 41.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hunt RH, Xiao SD, Megraud F, Leon-Barua R, Bazzoli F, van der Merwe S, Vaz Coelho LG, Fock M, Fedail S, Cohen H. Helicobacter pylori in developing countries. World Gastroenterology Organisation Global Guideline. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2011;20:299-304. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Tonkic A, Tonkic M, Lehours P, Mégraud F. Epidemiology and diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2012;17 Suppl 1:1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Khalifa MM, Sharaf RR, Aziz RK. Helicobacter pylori: a poor man’s gut pathogen? Gut Pathog. 2010;2:2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Jafri W, Yakoob J, Abid S, Siddiqui S, Awan S, Nizami SQ. Helicobacter pylori infection in children: population-based age-specific prevalence and risk factors in a developing country. Acta Paediatr. 2010;99:279-282. [PubMed] |

| 6. | McColl KE. Clinical practice. Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1597-1604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 529] [Cited by in RCA: 550] [Article Influence: 36.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yeomans ND. The ulcer sleuths: The search for the cause of peptic ulcers. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26 Suppl 1:35-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Fuccio L, Zagari RM, Eusebi LH, Laterza L, Cennamo V, Ceroni L, Grilli D, Bazzoli F. Meta-analysis: can Helicobacter pylori eradication treatment reduce the risk for gastric cancer? Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:121-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Huang JQ, Hunt RH. The evolving epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer. Can J Gastroenterol. 2003;17 Suppl B:18B-20B. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Parsonnet J, Hansen S, Rodriguez L, Gelb AB, Warnke RA, Jellum E, Orentreich N, Vogelman JH, Friedman GD. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1267-1271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1287] [Cited by in RCA: 1229] [Article Influence: 39.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, Atherton J, Axon AT, Bazzoli F, Gensini GF, Gisbert JP, Graham DY, Rokkas T. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection--the Maastricht IV/ Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2012;61:646-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1719] [Cited by in RCA: 1591] [Article Influence: 122.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 12. | Hunt RH, Sumanac K, Huang JQ. Review article: should we kill or should we save Helicobacter pylori? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15 Suppl 1:51-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lee YC, Chen TH, Chiu HM, Shun CT, Chiang H, Liu TY, Wu MS, Lin JT. The benefit of mass eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection: a community-based study of gastric cancer prevention. Gut. 2013;62:676-682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 275] [Cited by in RCA: 270] [Article Influence: 22.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rokkas T, Sechopoulos P, Robotis I, Margantinis G, Pistiolas D. Cumulative H. pylori eradication rates in clinical practice by adopting first and second-line regimens proposed by the Maastricht III consensus and a third-line empirical regimen. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:21-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Liou JM, Lin JT, Chang CY, Chen MJ, Cheng TY, Lee YC, Chen CC, Sheng WH, Wang HP, Wu MS. Levofloxacin-based and clarithromycin-based triple therapies as first-line and second-line treatments for Helicobacter pylori infection: a randomised comparative trial with crossover design. Gut. 2010;59:572-578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Gisbert JP, Calvet X, O’Connor A, Mégraud F, O’Morain CA. Sequential therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a critical review. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:313-325. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Kodaman N, Pazos A, Schneider BG, Piazuelo MB, Mera R, Sobota RS, Sicinschi LA, Shaffer CL, Romero-Gallo J, de Sablet T. Human and Helicobacter pylori coevolution shapes the risk of gastric disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:1455-1460. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Kanda T, Yokosuka O. Paradoxical role of Helicobacter pylori in Gastric cancer. Editorial. Biohelikon: Cancer and Clinical Research 2 2014; a12. |

| 19. | Olokoba AB, Obateru OA, Bojuwoye MO. Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy: A review of current trends. Niger Med J. 2013;54:1-4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Johnson-Henry KC, Mitchell DJ, Avitzur Y, Galindo-Mata E, Jones NL, Sherman PM. Probiotics reduce bacterial colonization and gastric inflammation in H. pylori-infected mice. Dig Dis Sci. 2004;49:1095-1102. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Lee JS, Paek NS, Kwon OS, Hahm KB. Anti-inflammatory actions of probiotics through activating suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) expression and signaling in Helicobacter pylori infection: a novel mechanism. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:194-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Franceschi F, Cazzato A, Nista EC, Scarpellini E, Roccarina D, Gigante G, Gasbarrini G, Gasbarrini A. Role of probiotics in patients with Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2007;12 Suppl 2:59-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Myllyluoma E, Ahlroos T, Veijola L, Rautelin H, Tynkkynen S, Korpela R. Effects of anti-Helicobacter pylori treatment and probiotic supplementation on intestinal microbiota. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2007;29:66-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Szajewska H, Horvath A, Piwowarczyk A. Meta-analysis: the effects of Saccharomyces boulardii supplementation on Helicobacter pylori eradication rates and side effects during treatment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;32:1069-1079. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Sachdeva A, Nagpal J. Effect of fermented milk-based probiotic preparations on Helicobacter pylori eradication: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized-controlled trials. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:45-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wang ZH, Gao QY, Fang JY. Meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of Lactobacillus-containing and Bifidobacterium-containing probiotic compound preparation in Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47:25-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Tong JL, Ran ZH, Shen J, Zhang CX, Xiao SD. Meta-analysis: the effect of supplementation with probiotics on eradication rates and adverse events during Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:155-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Gotteland M, Brunser O, Cruchet S. Systematic review: are probiotics useful in controlling gastric colonization by Helicobacter pylori? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:1077-1086. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52948] [Cited by in RCA: 47198] [Article Influence: 2949.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Jüni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, Savovic J, Schulz KF, Weeks L, Sterne JA. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18487] [Cited by in RCA: 24860] [Article Influence: 1775.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 31. | DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26739] [Cited by in RCA: 30428] [Article Influence: 780.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Ades AE, Lu G, Higgins JP. The interpretation of random-effects meta-analysis in decision models. Med Decis Making. 2005;25:646-654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 683] [Cited by in RCA: 658] [Article Influence: 32.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG. Analyzing data and undertaking meta-analyses. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 5.0.1. Oxford, UK: The Cochrane Collaboration 2008; chap 9. |

| 34. | Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39087] [Cited by in RCA: 46546] [Article Influence: 2115.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 35. | Altman DG, Bland JM. Interaction revisited: the difference between two estimates. BMJ. 2003;326:219. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Tobias A. Assessing the influence of a single study in meta-analysis. Stata Tech Bull. 1999;47:15-17. |

| 37. | Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629-634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34245] [Cited by in RCA: 40566] [Article Influence: 1448.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 38. | Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088-1101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10586] [Cited by in RCA: 12186] [Article Influence: 406.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Navarro-Rodriguez T, Silva FM, Barbuti RC, Mattar R, Moraes-Filho JP, de Oliveira MN, Bogsan CS, Chinzon D, Eisig JN. Association of a probiotic to a Helicobacter pylori eradication regimen does not increase efficacy or decreases the adverse effects of the treatment: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Ahmad K, Fatemeh F, Mehri N, Maryam S. Probiotics for the treatment of pediatric helicobacter pylori infection: a randomized double blind clinical trial. Iran J Pediatr. 2013;23:79-84. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Shavakhi A, Tabesh E, Yaghoutkar A, Hashemi H, Tabesh F, Khodadoostan M, Minakari M, Shavakhi S, Gholamrezaei A. The effects of multistrain probiotic compound on bismuth-containing quadruple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection: a randomized placebo-controlled triple-blind study. Helicobacter. 2013;18:280-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Kyriakos N, Papamichael K, Roussos A. A Lyophilized Form of Saccharomyces Boulardii Enhances the Helicobacter pylori Eradication Rates of Omeprazole-Triple Therapy in Patients With Peptic Ulcer Disease or Functional Dyspepsia. Hospital Chronicles. 2013;8:127-133. |

| 43. | Jiang YA, Ou XL, Wang JN. Efficacy of Bacillus licheniformis combined with PPI triple therapy in eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 2013;21:840-844. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Dajani AI, Abu Hammour AM, Yang DH, Chung PC, Nounou MA, Yuan KY, Zakaria MA, Schi HS. Do probiotics improve eradication response to Helicobacter pylori on standard triple or sequential therapy? Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:113-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Deguchi R, Nakaminami H, Rimbara E, Noguchi N, Sasatsu M, Suzuki T, Matsushima M, Koike J, Igarashi M, Ozawa H. Effect of pretreatment with Lactobacillus gasseri OLL2716 on first-line Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:888-892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Tolone S, Pellino V, Vitaliti G, Lanzafame A, Tolone C. Evaluation of Helicobacter Pylori eradication in pediatric patients by triple therapy plus lactoferrin and probiotics compared to triple therapy alone. Ital J Pediatr. 2012;38:63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Mirzaee V, Rezahosseini O. Randomized control trial: Comparison of Triple Therapy plus Probiotic Yogurt vs. Standard Triple Therapy on Helicobacter Pylori Eradication. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2012;14:657-666. [PubMed] |

| 48. | Manfredi M, Bizzarri B, Sacchero RI, Maccari S, Calabrese L, Fabbian F, De’Angelis GL. Helicobacter pylori infection in clinical practice: probiotics and a combination of probiotics + lactoferrin improve compliance, but not eradication, in sequential therapy. Helicobacter. 2012;17:254-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Du YQ, Su T, Fan JG, Lu YX, Zheng P, Li XH, Guo CY, Xu P, Gong YF, Li ZS. Adjuvant probiotics improve the eradication effect of triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:6302-6307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 50. | Bekar O, Yilmaz Y, Gulten M. Kefir improves the efficacy and tolerability of triple therapy in eradicating Helicobacter pylori. J Med Food. 2011;14:344-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Yoon H, Kim N, Kim JY, Park SY, Park JH, Jung HC, Song IS. Effects of multistrain probiotic-containing yogurt on second-line triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:44-48. [PubMed] |

| 52. | He QM, Li BS, Li YJ. Bifid Triple Viable facilitates the sequential therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Xiandai Xiaohua Ji Jieru Zhenliao. 2011;16:90-92. |

| 53. | Xu C, Xiao L, Zou H. [Effect of birid triple viable on peptic ulcer patients with Helicobacter pylori infection]. Zhongnan Daxue Xuebao Yixueban. 2010;35:1000-1004. [PubMed] |

| 54. | Yaşar B, Abut E, Kayadıbı H, Toros B, Sezıklı M, Akkan Z, Keskın Ö, Övünç Kurdaş O. Efficacy of probiotics in Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2010;21:212-217. [PubMed] |

| 55. | Wen JJ, Qiu RF. Effect of bifid triple viable on helicobacter pylori eradication. Gannan Yixueyuan Xuebao. 2010;30:902-903. |

| 56. | Song MJ, Park DI, Park JH, Kim HJ, Cho YK, Sohn CI, Jeon WK, Kim BI. The effect of probiotics and mucoprotective agents on PPI-based triple therapy for eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter. 2010;15:206-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Szajewska H, Albrecht P, Topczewska-Cabanek A. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial: effect of lactobacillus GG supplementation on Helicobacter pylori eradication rates and side effects during treatment in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48:431-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Hurduc V, Plesca D, Dragomir D, Sajin M, Vandenplas Y. A randomized, open trial evaluating the effect of Saccharomyces boulardii on the eradication rate of Helicobacter pylori infection in children. Acta Paediatr. 2009;98:127-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Francavilla R, Lionetti E, Castellaneta SP, Magistà AM, Maurogiovanni G, Bucci N, De Canio A, Indrio F, Cavallo L, Ierardi E. Inhibition of Helicobacter pylori infection in humans by Lactobacillus reuteri ATCC 55730 and effect on eradication therapy: a pilot study. Helicobacter. 2008;13:127-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Kim MN, Kim N, Lee SH, Park YS, Hwang JH, Kim JW, Jeong SH, Lee DH, Kim JS, Jung HC. The effects of probiotics on PPI-triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Helicobacter. 2008;13:261-268. [PubMed] |

| 61. | Huang JY, Huang HP, Shi BY. Effect of bifid triple viable with standard triple therapy on helicobacter pylori eradication. Shanghai Yiyao. 2008;29:552-554. |

| 62. | Imase K, Takahashi M, Tanaka A, Tokunaga K, Sugano H, Tanaka M, Ishida H, Kamiya S, Takahashi S. Efficacy of Clostridium butyricum preparation concomitantly with Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy in relation to changes in the intestinal microbiota. Microbiol Immunol. 2008;52:156-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Cindoruk M, Erkan G, Karakan T, Dursun A, Unal S. Efficacy and safety of Saccharomyces boulardii in the 14-day triple anti-Helicobacter pylori therapy: a prospective randomized placebo-controlled double-blind study. Helicobacter. 2007;12:309-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Park SK, Park DI, Choi JS, Kang MS, Park JH, Kim HJ, Cho YK, Sohn CI, Jeon WK, Kim BI. The effect of probiotics on Helicobacter pylori eradication. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54:2032-2036. [PubMed] |

| 65. | de Bortoli N, Leonardi G, Ciancia E, Merlo A, Bellini M, Costa F, Mumolo MG, Ricchiuti A, Cristiani F, Santi S. Helicobacter pylori eradication: a randomized prospective study of triple therapy versus triple therapy plus lactoferrin and probiotics. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:951-956. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Sahagún-Flores JE, López-Peña LS, de la Cruz-Ramírez Jaimes J, García-Bravo MS, Peregrina-Gómez R, de Alba-García JE. [Eradication of Helicobacter pylori: triple treatment scheme plus Lactobacillus vs. triple treatment alone]. Cir Cir. 2007;75:333-336. [PubMed] |

| 67. | Lionetti E, Miniello VL, Castellaneta SP, Magistá AM, de Canio A, Maurogiovanni G, Ierardi E, Cavallo L, Francavilla R. Lactobacillus reuteri therapy to reduce side-effects during anti-Helicobacter pylori treatment in children: a randomized placebo controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:1461-1468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Goldman CG, Barrado DA, Balcarce N, Rua EC, Oshiro M, Calcagno ML, Janjetic M, Fuda J, Weill R, Salgueiro MJ. Effect of a probiotic food as an adjuvant to triple therapy for eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection in children. Nutrition. 2006;22:984-988. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Sheu BS, Cheng HC, Kao AW, Wang ST, Yang YJ, Yang HB, Wu JJ. Pretreatment with Lactobacillus- and Bifidobacterium-containing yogurt can improve the efficacy of quadruple therapy in eradicating residual Helicobacter pylori infection after failed triple therapy. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:864-869. [PubMed] |

| 70. | Ziemniak W. Efficacy of Helicobacter pylori eradication taking into account its resistance to antibiotics. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2006;57 Suppl 3:123-141. [PubMed] |

| 71. | Sýkora J, Valecková K, Amlerová J, Siala K, Dedek P, Watkins S, Varvarovská J, Stozický F, Pazdiora P, Schwarz J. Effects of a specially designed fermented milk product containing probiotic Lactobacillus casei DN-114 001 and the eradication of H. pylori in children: a prospective randomized double-blind study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:692-698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Myllyluoma E, Veijola L, Ahlroos T, Tynkkynen S, Kankuri E, Vapaatalo H, Rautelin H, Korpela R. Probiotic supplementation improves tolerance to Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy--a placebo-controlled, double-blind randomized pilot study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:1263-1272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Duman DG, Bor S, Ozütemiz O, Sahin T, Oğuz D, Iştan F, Vural T, Sandkci M, Işksal F, Simşek I. Efficacy and safety of Saccharomyces boulardii in prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea due to Helicobacterpylori eradication. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;17:1357-1361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Shimbo I, Yamaguchi T, Odaka T, Nakajima K, Koide A, Koyama H, Saisho H. Effect of Clostridium butyricum on fecal flora in Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:7520-7524. [PubMed] |

| 75. | Cao YJ, Qu CM, Yuan Q. Control of intestinal flora alteration induced by eradication therapy of Helicobacter pylori infection in the elders. Weichagnbingxue He Ganbingxue Zazhi. 2005;14:195-199. |

| 76. | Nista EC, Candelli M, Cremonini F, Cazzato IA, Zocco MA, Franceschi F, Cammarota G, Gasbarrini G, Gasbarrini A. Bacillus clausii therapy to reduce side-effects of anti-Helicobacter pylori treatment: randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:1181-1188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Tursi A, Brandimarte G, Giorgetti GM, Modeo ME. Effect of Lactobacillus casei supplementation on the effectiveness and tolerability of a new second-line 10-day quadruple therapy after failure of a first attempt to cure Helicobacter pylori infection. Med Sci Monit. 2004;10:CR662-CR666. [PubMed] |

| 78. | Guo JB, Yang PF, Wang MT. The application of clostridium butyricum to the eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Zhonghua Fubujibing Zazhi. 2004;4:163-165. |

| 79. | Sheu BS, Wu JJ, Lo CY, Wu HW, Chen JH, Lin YS, Lin MD. Impact of supplement with Lactobacillus- and Bifidobacterium-containing yogurt on triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1669-1675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Cremonini F, Di Caro S, Covino M, Armuzzi A, Gabrielli M, Santarelli L, Nista EC, Cammarota G, Gasbarrini G, Gasbarrini A. Effect of different probiotic preparations on anti-helicobacter pylori therapy-related side effects: a parallel group, triple blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2744-2749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 229] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Armuzzi A, Cremonini F, Bartolozzi F, Canducci F, Candelli M, Ojetti V, Cammarota G, Anti M, De Lorenzo A, Pola P. The effect of oral administration of Lactobacillus GG on antibiotic-associated gastrointestinal side-effects during Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:163-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Armuzzi A, Cremonini F, Ojetti V, Bartolozzi F, Canducci F, Candelli M, Santarelli L, Cammarota G, De Lorenzo A, Pola P. Effect of Lactobacillus GG supplementation on antibiotic-associated gastrointestinal side effects during Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy: a pilot study. Digestion. 2001;63:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Canducci F, Armuzzi A, Cremonini F, Cammarota G, Bartolozzi F, Pola P, Gasbarrini G, Gasbarrini A. A lyophilized and inactivated culture of Lactobacillus acidophilus increases Helicobacter pylori eradication rates. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:1625-1629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Duvall S, Tweedie R. A nonparametric ‘’trim and fill’’ method for assessing publication bias in meta-analysis. J Am Stat Assoc. 2000;95:89-98. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 386] [Cited by in RCA: 388] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Zagari RM, Bianchi-Porro G, Fiocca R, Gasbarrini G, Roda E, Bazzoli F. Comparison of 1 and 2 weeks of omeprazole, amoxicillin and clarithromycin treatment for Helicobacter pylori eradication: the HYPER Study. Gut. 2007;56:475-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Patel A, Shah N, Prajapati JB. Clinical application of probiotics in the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection--a brief review. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2014;47:429-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Gao XW, Mubasher M, Fang CY, Reifer C, Miller LE. Dose-response efficacy of a proprietary probiotic formula of Lactobacillus acidophilus CL1285 and Lactobacillus casei LBC80R for antibiotic-associated diarrhea and Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea prophylaxis in adult patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1636-1641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Giorgio F, Principi M, De Francesco V, Zullo A, Losurdo G, Di Leo A, Ierardi E. Primary clarithromycin resistance to Helicobacter pylori: Is this the main reason for triple therapy failure? World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol. 2013;4:43-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Megraud F. Helicobacter pylori and antibiotic resistance. Gut. 2007;56:1502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Georgopoulos SD, Papastergiou V, Karatapanis S. Helicobacter pylori Eradication Therapies in the Era of Increasing Antibiotic Resistance: A Paradigm Shift to Improved Efficacy. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:757926. [PubMed] |

| 91. | Graham DY, Shiotani A. New concepts of resistance in the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infections. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;5:321-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 270] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | De Francesco V, Giorgio F, Hassan C, Manes G, Vannella L, Panella C, Ierardi E, Zullo A. Worldwide H. pylori antibiotic resistance: a systematic review. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2010;19:409-414. [PubMed] |

| 93. | Gisbert JP, Pérez-Aisa A, Bermejo F, Castro-Fernández M, Almela P, Barrio J, Cosme A, Modolell I, Bory F, Fernández-Bermejo M. Second-line therapy with levofloxacin after failure of treatment to eradicate helicobacter pylori infection: time trends in a Spanish Multicenter Study of 1000 patients. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;47:130-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Salari P, Nikfar S, Abdollahi M. A meta-analysis and systematic review on the effect of probiotics in acute diarrhea. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets. 2012;11:3-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Ringel-Kulka T, Palsson OS, Maier D, Carroll I, Galanko JA, Leyer G, Ringel Y. Probiotic bacteria Lactobacillus acidophilus NCFM and Bifidobacterium lactis Bi-07 versus placebo for the symptoms of bloating in patients with functional bowel disorders: a double-blind study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45:518-525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Quigley EM. The enteric microbiota in the pathogenesis and management of constipation. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;25:119-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Jayasimhan S, Yap NY, Roest Y, Rajandram R, Chin KF. Efficacy of microbial cell preparation in improving chronic constipation: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Nutr. 2013;32:928-934. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Miller LE, Ouwehand AC. Probiotic supplementation decreases intestinal transit time: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:4718-4725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 99. | Bardhan PK. Epidemiological features of Helicobacter pylori infection in developing countries. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:973-978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Kamdeu Fansi AA, Guertin JR, LeLorier J. Savings from the use of a probiotic formula in the prophylaxis of antibiotic-associated diarrhea. J Med Econ. 2012;15:53-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |