Published online Mar 21, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i11.3409

Peer-review started: September 9, 2014

First decision: October 14, 2014

Revised: October 23, 2014

Accepted: November 11, 2014

Article in press: November 11, 2014

Published online: March 21, 2015

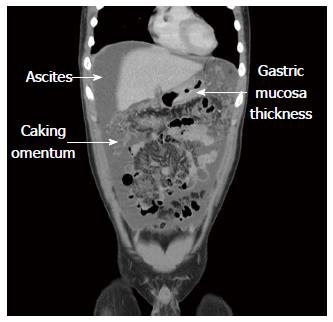

Gastric adenocarcinoma is quite rare in children and as a result very little experience has been reported on with regards to clinical presentation, treatment and outcome. We describe the case of a 16-year-old boy presenting with abdominal fullness and poor appetite for 7 d. Sonography showed massive ascites and computed tomography imaging revealed the presence of gastric mucosa thickness with omentum caking. The diagnosis of gastric adenocarcinoma was biopsy-proven endoscopically. Despite gastric adenocarcinoma being quite rare in the pediatric patient population, we should not overlook the possibility of gastric adenocarcinoma when a child presents with distended abdomen and massive ascites.

Core tip: Gastric adenocarcinoma is rare in pediatric patient. It should be suspected in a child with gastric ulcers and massive ascites. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and endoscopic biopsies are crucial in children with vague gastrointestinal symptoms and massive ascites in whom CT fails to demonstrate the primary site of the malignancy.

- Citation: Lin CH, Lin WC, Lai IH, Wu SF, Wu KH, Chen AC. Pediatric gastric cancer presenting with massive ascites. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(11): 3409-3413

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i11/3409.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i11.3409

Primary gastric adenocarcinoma is a rare cancer in children, and occurs in 0.05% of all childhood cancers[1]. The initial clinical presentations were mostly nonspecific abdominal symptoms, such as dyspepsia, epigastric pain, nausea/vomiting, weight loss, and gastrointestinal bleeding. The etiology of gastric adenocarcinoma in adults could be related to lifestyle factors or infectious factors[2]. However, the role of these factors in children is unknown. The prognosis for the gastric adenocarcinoma in children is very poor, with a median survival time of 5 mo and average survival time of 7.5 mo[3], and relatively little information exists regarding the 5-year disease-free survival rate for children[3-5]. Because of its rarity, the diagnosis and treatment in a pediatric population with gastric adenocarcinoma remains challenging. Herein we describe a 16-year-old boy with gastric adenocarcinoma who presented with abdominal fullness with massive ascites.

A 16-year-old boy presented with abdominal fullness and poor appetite for one week. It took approximately 2 wk from initial symptom occurrence to patient hospitalization. A body weight loss of 8 kilograms was noted initially. The diet habits of the patient were standard without any obvious personal favorites regarding food. The patient also had the social habit of smoking with a consumption of 1 pack of cigarettes every 3 d for about 1 year. His family history showed gastric cancer in his grandfather, who died at the age of 51 years. The physical examination show distended abdominal wall with dull on percussion, and epigastric local tenderness. Neck lymph nodes were enlarged on level V. No resistance and no enlargement of liver or spleen were noted.

Laboratory investigations revealed normal results except for mild leukocytosis (11.19 × 1000/μL, normal range: 3.99-10.39 × 1000/μL) with predominant neutrophil (80.4%, normal range: 40%-74%) and decreased lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level (90 U/L, normal range: 98-192 U/L). The level of tumor marker was significantly increased in CA125 (109.1 U/mL, normal range: < 35 U/mL) but was normal in CEA (0.51 ng/mL, normal range: < 5 ng/mL) and CA199 (6.8 U/mL, normal range: < 35 U/mL).

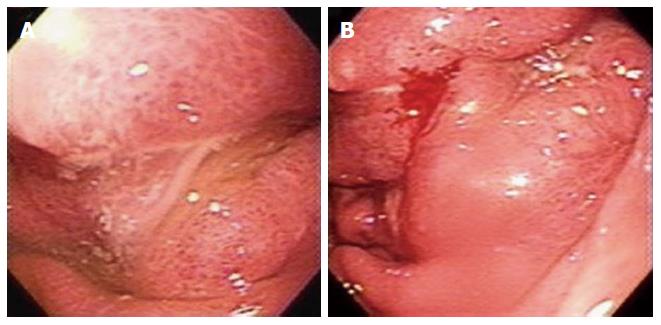

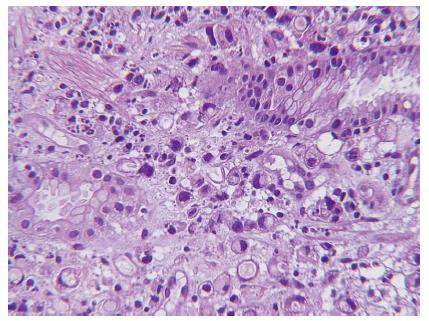

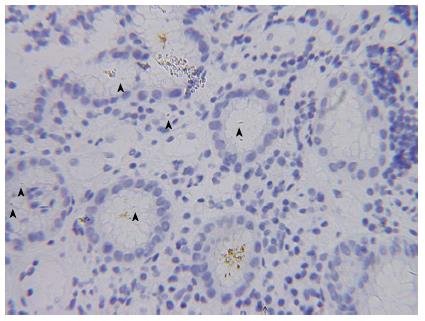

Abdominal sonography confirmed massive ascites. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan revealed massive ascites, gastric mucosa thickness, and caking omentum (Figure 1). The gastroscopy revealed a large bizarre gastric ulcer (A2) (4 cm × 4 cm in size) which appeared as a snake skin with multiple nodular appearance over peri-antrum area (Figure 2). Four biopsy specimens were obtained on the margin of the ulcers during histological examination, and poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma with the presence of signet ring cells was observed (Figure 3). Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) were also detected in the patient’s biopsy tissue specimens (Figure 4).

Study of the ascites showed RBC count: 4000/μL, and WBC count: 10707/μL with neutrophil 89% and biochemistry revealed glucose: 97 mg/dL, LDH: 288 U/L, total protein: 4.2 g/dL, albumin: 2.9 g/dL (normal range: 3.8-5.3 g/dL). The cytology of ascites from abdominal tapping reported malignant cells. The genetic work-up for our patient was all shown to be normal.

The ascites study revealed many tumor nests, which were all negative for CD45, CD3, CD19, CD20, CD33, myeloperoxidase and TdT in the immunohistochemical study. These results indicated that lymphoma was not likely.

The infectious factor of Helicobacter bacilli was evident in pathology from gastric biopsy. However, the EBV DNA PCR study was negative (< 600 copies). Hepatitis was excluded as both HBsAg and HCV antibody were negative.

No local radiotherapy or surgery was planned because of extensive metastatic disease (the TNM staging was T4N × M1, IV); the patient was placed on steroid as dexamethasone phosphate and a chemotherapy regimen of oxaliplatin and capecitabine. The patient died 10 mo after diagnosis.

Gastric adenocarcinoma is primarily a disease that impacts older individuals, and is generally rare in individuals under the age of 30 years, and even rarer in the children[6-8]. The presentation and biologic behavior of primary gastric adenocarcinoma in children are similar to those seen in adults. However, the etiology of pediatric gastric cancer is more unclear and may be associated with gene mutations[9], the incidence is very rare, the management is not well-established, and is associated with very poor outcome. In a review of the related literature, Sasaki et al[3] previously reported 22 cases of primary gastric adenocarcinoma under the age of 21 years, and Lu et al[8] recently reported 16 cases with gastric cancer under the age of 18 years[8]. Of these 39 cases, only 2 patients survived over 2 years (102 mo and 30 mo, respectively), which demonstrated that primary gastric adenocarcinoma during childhood is strongly associated with a very poor clinical outcome as compared to adults. This is possibly because of its rarity and nonspecific presentation results in a failure to consider potential malignancy and thus contributes to a delay in diagnosis, and as a result, few cases of appropriate clinical treatment.

The most common presentations in pediatric gastric adenocarcinoma are abdominal pain and vomiting, which may mimic other disease of acute abdomen[10,11]. Others symptoms include, hematemesis, melena and weight loss. In general, pediatric physician would not routinely do more invasive examination technique on pediatric patient with nonspecific presentation. Therefore, early gastric cancer is rare on children, and almost pediatric gastric adenocarcinoma was diagnosed as terminal stage, which quite different from adult. Our patient complained of abdominal fullness for one week, and massive ascites were found by sonography. The major causes of ascites in pediatric patients are related to diseases of the liver and kidney. However, ascites can also result from heart disease, malignancy, peritonitis, eosinophilic gastroenteritis and pancreatitis. The upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed on our patient because of gastric mucosa thickness with caking omentum seen by CT, and a pathologic result of gastric adenocarcinoma was proven by biopsy. Although ascites due to peritoneal tumor seeding and metastasis are well-known symptoms in adult patients with gastric cancer, they are not frequently encountered in children. According Lu et al[8] in a review of 16 cases of pediatric gastric adenocarcinoma, only one patient presented with abdominal fullness. In this case, the importance of gastroscopy for prompt diagnosis in pediatric patients with ascites is emphasized[2,12,13].

The most important risk factor of pediatric adenocarcinoma is H. pylori infection, which can cause chronic active inflammation in the gastric mucosa; and furthermore, gastric atrophy can develop predominantly in the antrum[1,4,14]. Pediatric patient got H. pylori infection at a very early age has been related to a much higher gastric cancer risk, especially in the setting of a positive family history of gastric cancer[15,16]. Other risk factors such high intake of salt, smoked food, nitrates and carbohydrates, alcohol consumption, smoking, blood groups, and cancer family history are associated with gastric adenocarcinoma in adults, but its role in children is unknown[4]. Taken together, several risk factors for tumor development were present in our patient, including his grandfather dying of gastric cancer, having a history of smoking for one year, and H. pylori infection proven by biopsy. Despite the patient having H. pylori infection, we can suspect the gastric adencarcinoma may be related to an organism infection.

Because gastric adenocarcinoma rarely affects children, the management of this disease in children is not well-established, and must be based on the principles used in adults for the time being. Radical gastrectomy with extended lymph node dissection is the only curative management in patients with localized gastric adenocarcinoma; however, recurrence within 2 years is still quite common[1,4,16,17]. Preoperative chemoradiation or post-operative adjuvant chemoradiation is commonly practiced and has been shown to improve survival[18]. In the patients with unresectable tumors, such as our patient who had extensive metastatic disease, palliative chemotherapy, such as 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, adriamycin, cisplatin, etoposide, and epirubicin-containing protocols can be effective when attempting to control the symptoms, and may provide some limited improvement in terms of survival rates.

In conclusion, although gastric adenocarcinoma is rare in children, it should be suspected in a child with gastric ulcers and massive ascites. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and endoscopic biopsies are crucial in children with vague gastrointestinal symptoms and massive ascites in whom CT fails to demonstrate the primary site of the malignancy.

The main symptom is abdominal fullness and poor appetite for 7 d.

The physical sign of the patient was massive ascites; upon physical examination show distended abdominal wall with dull on percussion, and epigastric local tenderness. Neck lymph nodes were enlarged on level V.

The differential diagnosis of massive ascites included heart disease, malignancy, peritonitis, eosinophilic gastroenteritis and pancreatitis.

Laboratory investigations revealed normal results except for mild leukocytosis (11.19 × 1000/μL, normal range: 3.99-10.39 × 1000/μL) with predominant neutrophil (80.4%, normal range: 40%-74%) and decreased lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level (90 U/L, normal range: 98-192 U/L). The level of tumor marker was significantly increased in CA125 (109.1 U/mL, normal range: < 35 U/mL) but was normal in CEA (0.51 ng/mL, normal range: < 5 ng/mL) and CA199 (6.8 U/mL, normal range: < 35 U/mL).

Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan revealed massive ascites, gastric mucosa thickness, and caking omentum. The gastroscopy revealed a large bizarre gastric ulcer (A2) (4 cm × 4 cm in size) which appeared as a snake skin with multiple nodular appearance over peri-antrum area.

Histological examination revealed poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma with the presence of signet ring cells was observed. Helicobacter pylori were also detected in the patient’s biopsy tissue specimens.

No local radiotherapy or surgery was planned because of extensive metastatic disease; the patient was placed on steroid as dexamethasone phosphate and a chemotherapy regimen of oxaliplatin and capecitabine.

Very few cases of pediatric gastric adenocarcinoma have been reported in the literature. The clinical and pathological characteristics of pediatric gastric adenocarcinoma remain unclear and the treatment is controversial.

Gastric adenocarcinoma, is a rare disease in children that primarily affects adults.

This case report presents the clinical characteristics of gastric adenocarcinoma and also discusses the diagnosis of gastric adenocarcinoma. The authors recommend that upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and endoscopic biopsies are crucial in children with vague gastrointestinal symptoms and massive ascites in whom CT fails to demonstrate the primary site of the malignancy.

The authors have described a case of gastric adenocarcinoma presenting with initial presentation of massive ascites. The article highlights the rare clinical characteristics of this tumor and provides insights into the diagnostic implications.

P- Reviewer: Codoner-Franch P, Qi F S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Harting MT, Blakely ML, Herzog CE, Lally KP, Ajani JA, Andrassy RJ. Treatment issues in pediatric gastric adenocarcinoma. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39:e8-e10. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 25] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Milne AN, Carneiro F, O’Morain C, Offerhaus GJ. Nature meets nurture: molecular genetics of gastric cancer. Hum Genet. 2009;126:615-628. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 145] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sasaki H, Sasano H, Ohi R, Imaizumi M, Shineha R, Nakamura M, Shibuya D, Hayashi Y. Adenocarcinoma at the esophageal gastric junction arising in an 11-year-old girl. Pathol Int. 1999;49:1109-1113. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Subbiah V, Varadhachary G, Herzog CE, Huh WW. Gastric adenocarcinoma in children and adolescents. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;57:524-527. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 29] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Schwartz MG, Sgaglione NA. Gastric carcinoma in the young: overview of the literature. Mt Sinai J Med. 1984;51:720-723. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Strobel CT, Smith LE, Euler AR. Primary gastric adenocarcinoma in the pediatric population. J Pediatr. 1978;92:850-851. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Goldthorn JF, Canizaro PC. Gastrointestinal malignancies in infancy, childhood, and adolescence. Surg Clin North Am. 1986;66:845-861. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lu J, Huang CM, Zheng CH, Li P, Xie JW, Wang JB, Lin JX. [Gastric carcinoma in a 12-year-old girl: a case report and literature review]. Zhonghua Weichang Waike Zazhi. 2012;15:967-970. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Chang VY, Federman N, Martinez-Agosto J, Tatishchev SF, Nelson SF. Whole exome sequencing of pediatric gastric adenocarcinoma reveals an atypical presentation of Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60:570-574. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wu HP, Yang WC, Wu KH, Chen CY, Fu YC. Diagnosing appendicitis at different time points in children with right lower quadrant pain: comparison between Pediatric Appendicitis Score and the Alvarado score. World J Surg. 2012;36:216-221. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 27] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lee YT, Ng EK, Hung LC, Chung SC, Ching JY, Chan WY, Chu WC, Sung JJ. Accuracy of endoscopic ultrasonography in diagnosing ascites and predicting peritoneal metastases in gastric cancer patients. Gut. 2005;54:1541-1545. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 59] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Aydoğan A, Corapçioğlu F, Elemen EL, Tugay M, Gürbüz Y, Oncel S. A case report: gastric adenocarcinoma in childhood. Turk J Pediatr. 2009;51:489-492. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Peek RM, Blaser MJ. Helicobacter pylori and gastrointestinal tract adenocarcinomas. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:28-37. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1317] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1298] [Article Influence: 59.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kato S, Kikuchi S, Nakajima S. When does gastric atrophy develop in Japanese children? Helicobacter. 2008;13:278-281. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Brenner H, Arndt V, Stürmer T, Stegmaier C, Ziegler H, Dhom G. Individual and joint contribution of family history and Helicobacter pylori infection to the risk of gastric carcinoma. Cancer. 2000;88:274-279. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Blaser MJ, Chyou PH, Nomura A. Age at establishment of Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric carcinoma, gastric ulcer, and duodenal ulcer risk. Cancer Res. 1995;55:562-565. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Slotta JE, Heine S, Kauffels A, Krenn T, Grünhage F, Wagner M, Graf N, Schilling MK, Schuld J. Gastrectomy with isoperistaltic jejunal parallel pouch in a 15-year-old adolescent boy with gastric adenocarcinoma and autosomal recessive agammaglobulinemia. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46:e21-e24. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Varadhachary G, Ajani JA. Preoperative and adjuvant therapies for upper gastrointestinal cancers. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2005;5:719-725. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |