Published online Mar 21, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i11.3394

Peer-review started: August 6, 2014

First decision: August 27, 2014

Revised: September 8, 2014

Accepted: October 15, 2014

Article in press: October 15, 2014

Published online: March 21, 2015

Processing time: 225 Days and 24 Hours

We herein report a case of bronchial bleeding after radical esophagectomy that was treated with lobectomy. A 65-year-old male who underwent subtotal esophagectomy with three-field lymph node dissection for esophageal carcinoma was referred to our hospital because of sudden hemoptysis. After the esophagectomy, bilateral vocal cord paralysis was observed, and the patient suffered from repeated episodes of aspiration pneumonia. Bronchoscopy revealed hemosputum in the right middle lobe bronchus, and contrast-enhanced computed tomography showed tortuous arteries arising from the right inferior phrenic artery and left subclavian artery toward the right middle lobe bronchus. Although bronchial arterial embolization was performed twice to control the recurrent hemoptysis, the procedures were unsuccessful. Right middle lobectomy was therefore performed via video-assisted thoracic surgery. Engorged bronchial arterys with medial hypertrophy and overgrowth of the small branches were noted near the bronchus in the resected specimen. The patient recovered uneventfully and was discharged on postoperative day 14.

Core tip: To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of bronchial bleeding suspected to arise from ectopic/collateral bronchial arteries after radical esophagectomy with three-field lymphadenectomy for esophageal carcinoma. Such clinical course after esophagectomy for esophageal carcinoma is quite meaningful, especially in cases of postoperative recurrent aspiration pneumonia due to bilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve injury.

- Citation: Kitajima T, Momose K, Lee S, Haruta S, Ueno M, Shinohara H, Fujimori S, Fujii T, Takei R, Kohno T, Udagawa H. Bronchial bleeding caused by recurrent pneumonia after radical esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(11): 3394-3401

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i11/3394.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i11.3394

Hemoptysis is an alarming symptom and a potentially life-threatening complication that can occur in a variety of infectious, inflammatory, and cancerous diseases of the chest. In general, there are several causes of hemoptysis, including bronchogenic carcinoma, chronic inflammatory lung disease due to bronchiectasis and various infections, although the majority of cases are due to tuberculosis[1,2].

According to previous reports, surgeons should consider the potential for locoregional recurrence and aorto-bronchial fistula[3,4] or gastro-tracheobronchial fistula formation[5,6] in cases of hemoptysis after esophagectomy for esophageal carcinoma. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of bronchial bleeding suspected to have arisen from ectopic/collateral bronchial arteries after radical esophagectomy with three-field lymphadenectomy for esophageal carcinoma. This clinical course after esophagectomy for esophageal carcinoma is quite meaningful, especially in cases of postoperative recurrent aspiration pneumonia due to bilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve injury.

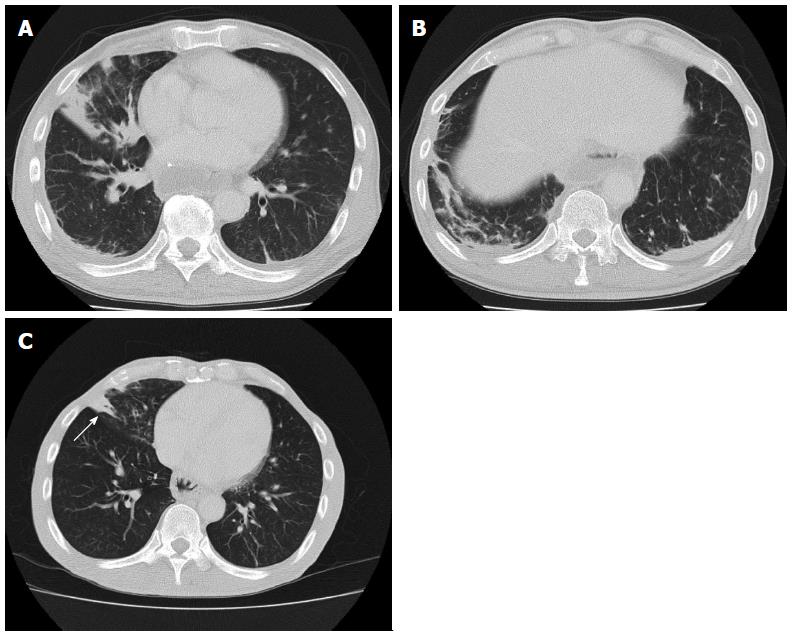

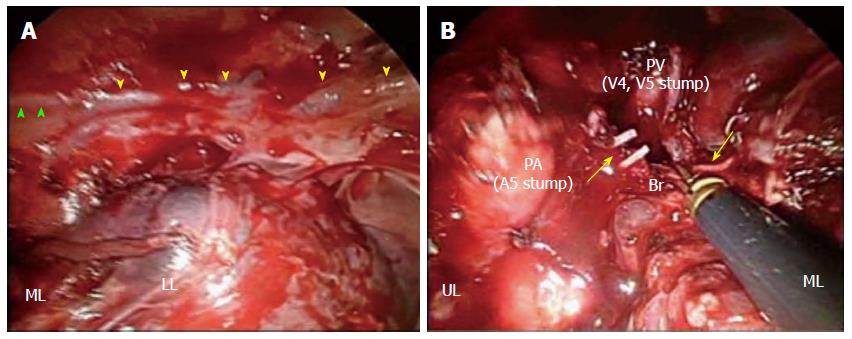

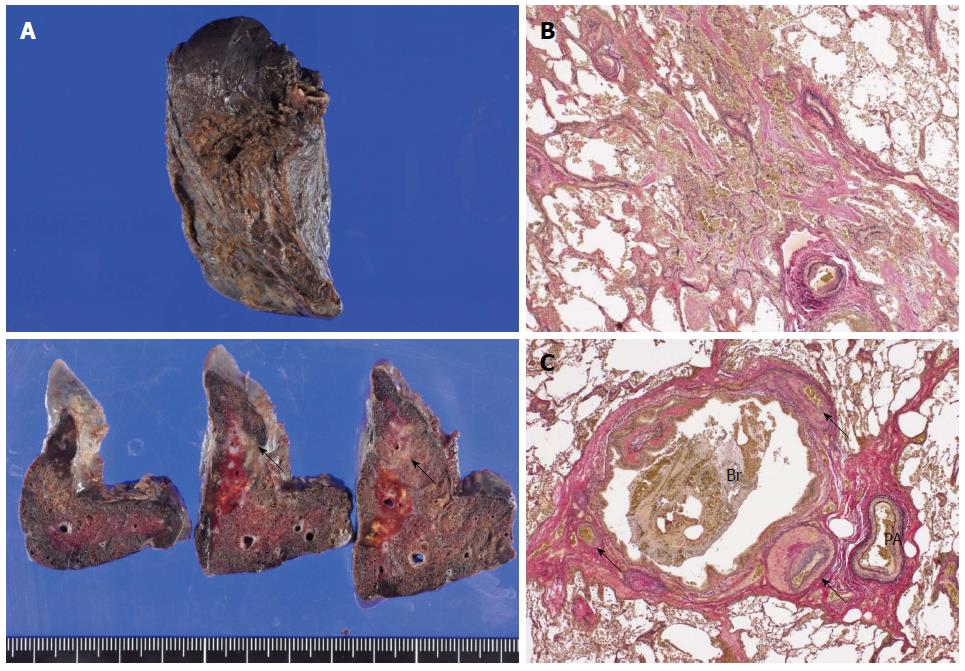

A 65-year-old Japanese male who underwent esophagectomy was admitted to our hospital with sudden hemoptysis. He had smoked 20 cigarettes a day since his twenties and consumed alcohol only on social occasions without regular habitual drinking. On preoperative examination, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy demonstrated a pedunculated lesion located on the posterior wall of the upper thoracic esophagus 21-23 cm distal from the incisors. A biopsy from the pedunculated lesion revealed a well-differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma. The patient had undergone radical esophagectomy with three-field lymphadenectomy 19 mo before the current admission. Surgical reconstruction was performed via the posterior mediastinal route using a gastric conduit, followed by esophagogastrostomy and tracheostomy placement, as bilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve injury was noted. The right bronchial artery (BA), which is usually identified and preserved, was suspected to be absent because it was not identified despite a meticulous investigation. Histopathologically, the pedunculated tumor consisted of mixed adenoendocrine carcinoma. None of the 79 widely dissected lymph nodes exhibited metastasis, and no lymphatic invasion was detected. The patient was diagnosed with stage IA (pT1bN0M0) disease according to the 7th edition of the UICC/AJCC TNM classification. Postoperatively, bilateral vocal cord paralysis was observed, and the patient suffered from repeated episodes of aspiration pneumonia for six months after the surgery (Figure 1A, B). Because the main cause of the patient’s repeated aspiration was postprandial reflux of gastric contents, resection of the pyloric ring and diversion of the gastric conduit in a Roux-en Y fashion was performed to prevent further aspiration of the regurgitant. Thus, it took approximately eight months for the patient to safely resume oral intake. He was discharged from our hospital nine months after surgery. Although the bilateral vocal cord paralysis did not improve, he was able to maintain proper dietary habits through dysphagia rehabilitation and adopting a soft diet. Although no further episodes of aspiration pneumonia or evidence of tumor recurrence were noted during follow-up, consolidation in the right middle lobe, which was observed at discharge, persisted by computed tomography (CT) that was performed immediately before this episode (Figure 1C). A total of 19 mo after esophagectomy, the patient began to cough up small amounts of blood and was admitted to a regional hospital. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy did not reveal any bleeding from the gastric conduit. Meanwhile, bronchoscopy revealed hemosputum in the entrance of the right middle lobe bronchus; bleeding from the peripheral bronchus was suspected to be the primary cause of this complication. Although the patient exhibited a stable clinical course under conservative therapy, sudden hemoptysis was noted one week after onset, and he was transferred to our hospital. Laboratory tests performed at the time of admission indicated anemia and inflammation. The hemoglobin level was 8.8 g/dL, and the C-reactive protein level was elevated at 16.1 mg/dL. However, the levels of serum Aspergillus antigens, β-D glucan, and tumor markers, such as carcinoembryonic antigen, squamous cell carcinoma antigen, and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 were all within normal limits. The patient demonstrated a negative blood culture, although Klebsiella pneumoniae and Pseudomonas aeruginosa were detected in a sputum culture. Additionally, he was negative for tuberculosis. While bronchoscopy revealed no active hemorrhaging from the respiratory tract, a small level of hemosputum was observed in the entrance of the right middle lobe bronchus (Figure 2A). CT and chest radiography revealed a massive infiltrative shadow in the right middle lobe with atelectasis in the right lower lobe (Figure 2B, C). In addition, bronchoscopy and CT revealed no protruding lesions, suggesting bronchial invasion of the tumor and/or gastro-tracheobronchial/aorto-bronchial fistula formation in the bronchus. With respect to the vessel anatomy, contrast-enhanced CT showed a tortuous artery ascending from the right inferior phrenic artery directly arising from the aorta near the celiac trunk toward the right middle bronchus (Figure 3A); in addition, we observed several tortuous arteries with hypervascularity arising from the left subclavian artery, which descended obliquely along the right main bronchus (Figure 3B). Although we considered these engorged and tortuous vessels to be ectopic/collateral BAs that caused the patient’s hemoptysis, identifying the responsible vessel was difficult because of his hemostasis. Considering the difficulty in performing embolization of the ectopic BAs arising from the left subclavian artery, we first attempted to embolize the right collateral BA arising from the inferior phrenic artery. On the next day from admission, a bronchial arterial embolization (BAE) procedure was performed. No aorto-bronchial fistulas were detected on aortography. The right collateral BA was successfully embolized with gelatin sponge particles (Figure 3C). However, the day after the BAE procedure, the level of recurrent hemoptysis was estimated to be approximately 200-300 mL, and bronchoscopy revealed bleeding from the same site as that observed at disease onset. On the third day after admission, a second BAE procedure was emergently performed. Although selective embolization of the ectopic BAs arising from the left subclavian artery was also performed (Figure 3D), CT conducted after the second BAE procedure revealed that the arterial blood supply to the right middle lobe bronchus was decreased but not completely blocked. Because we posited that performing additional embolization of the ectopic vessels would be difficult due to the tortuosity and fragility of the vessels, we planned to perform surgical resection after the patient’s hemodynamic parameters stabilized. On the ninth day after admission, right middle lobectomy was performed via video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS). With respect to the intraoperative findings, the presence of a BA arising from the right inferior phrenic artery was confirmed; the vessel was black in color as a result of the first BAE procedure (Figure 4A). Although a few engorged right BAs streaming into the right middle lobe were dissected at the level of bifurcation of the middle lobe bronchus (Figure 4B), it was difficult to detect the root of the dissected arteries. In addition, whitish pleural thickening of the right middle and lower lobes was significant. Grossly, an ill-demarcated whitish area with a brownish tint was observed on the cut surface of the resected lung (Figure 5A). Histopathologically, organizing pneumonia with the accumulation of hemosiderin-laden macrophages was detected (Figure 5B). The bronchus was enlarged, and engorged BAs with medial hypertrophy and overgrowth of small branches were also noted near the bronchus, although the bleeding origin was not identified (Figure 5C). The patient recovered uneventfully, with the absence of recurrent hemoptysis, and was discharged from our hospital on postoperative day 14. At the time of this writing, he has been doing well for four months, with no evidence of recurrence or hemoptysis.

With respect to the major clinical conditions and/or complications inducing hemoptysis after esophagectomy for esophageal carcinoma, surgeons should consider the possibility of locoregional recurrence and aorto-bronchial[3,4] or gastro-tracheobronchial[5,6] fistula formation. We performed a search of PubMed using the following key words: “hemoptysis/bronchial bleeding/respiratory tract hemorrhage after esophagectomy”. Fistula formation after esophagectomy is an uncommon and invariably life-threatening complication if left untreated. Only a few cases of aorto-bronchial fistulas after esophagectomy have been reported worldwide in the published literature to date; among the two cases identified in PubMed, gastric tube reconstruction was performed via the retrosternal or posterior mediastinal route, and both fistulas were detected between the left main bronchus and descending aorta[3,4]. In contrast, several cases of gastro-tracheobronchial fistulas after esophagectomy have been reported, and tumor recurrence, erosion injury, and radiation necrosis are considered common causes of the late development of these fistulas[5,6]. In the present case, these three conditions were excluded because no protruding/occupied lesions or either fistula type were observed on CT, BAE, or bronchoscopy. In addition, the stage of disease (IA, pT1bN0M0), the presence of bleeding from the peripheral bronchus suspicious on bronchoscopy, and the lack of ulceration necrosis or erosion in the gastric conduit on follow-up gastrointestinal endoscopy supported the exclusion of these clinical conditions.

Based on the intraoperative and pathological findings observed in this case, we judged that the causative vessels of the patient’s hemoptysis were the tortuous and engorged arteries arising from the left subclavian artery along the right main bronchus. Retrospectively, orthotopic bilateral BAs originating from the descending aorta at the level of the sixth thoracic vertebra (T6) were detected on contrast-enhanced CT prior to esophagectomy, whereas the ectopic/collateral arteries arising from the right phrenic artery and left subclavian artery were not. However, it was difficult to precisely evaluate the presence of the ectopic/collateral arteries preoperatively because multiphase contrast-enhanced CT is not routinely performed. According to previous studies, ectopic BAs are defined as arteries originating outside the level of T5-T6 of the thoracic aorta[1,7,8]. Ectopic BAs, which extend along the course of the major bronchus, can be distinguished from collateral arteries arising from the non-bronchial systemic arteries that enter the lung parenchyma via the pulmonary ligament or adherent pleura and exhibit a course that is not parallel to the bronchus[1,7]. Additionally, some studies have reported that chronic inflammation of the lungs is associated with engorgement of the BAs[9,10] in which the collateral blood supply from non-bronchial systemic arteries is vascularized and recruited under conditions of chronic inflammation and may arise from branches of the subclavian, axillary, or internal mammary arteries, as well as infradiaphragmatic branches from the inferior phrenic and left gastric arteries[1,11]. In the present case, it was more appropriate to consider the engorged BAs arising from the left subclavian artery to be inherent, having developed after esophagectomy rather than being completely vascularized, due to the dissection of the orthotopic right BAs during radical lymphadenectomy and the effects of postoperative recurrent aspiration pneumonia. These BAs may have been classified as ectopic BAs because they extended along the course of the right main bronchus[1,7]. Alternatively, the tortuous right BA arising from the right inferior phrenic artery may have been classified as a collateral artery arising from non-bronchial systemic arteries because CT detected this artery extending along the pleural surface[1,7]. The frequency of ectopic BAs arising from the subclavian and inferior phrenic arteries is reported to be 10%-13% of all ectopic BAs detected on CT angiograms[12,13].

The mechanism underlying the persistent pneumonia in the right middle lobe observed in this case is thought to be similar to that underlying middle lobe syndrome. This syndrome is characterized by the recurrent or chronic collapse of the right middle lobe and can be classified into obstructive and non-obstructive types[14-16]. Although the etiology of the non-obstructive type has not been fully elucidated, inefficient collateral ventilation, infection, and inflammation are considered to play key roles. Pathophysiologically, the long length and narrow diameter of the middle lobe bronchus can result in poor conditions for drainage[17]. Additionally, collateral ventilation is often prevented by the presence of deep fissures of the middle lobe with few parenchymal connections[18]. In the present case, these anatomical characteristics may also have contributed to the persistence of pneumonia of the right middle lobe, whereas consolidation of the right lower lobe was resolved (Figure 1C).

Furthermore, this case could be diagnosed as secondary racemose hemangioma of BA as these cases have been reported in Japan. Such cases are diagnosed by the existence of remarkably tortuous, enhancing, and meandering BAs[19]. Hyperplastic changes that develop after inflammation, such as bronchiectasis, bronchitis, and pneumonia, are classified as secondary racemose hemangioma[20]. However, in this case, the definitive diagnosis was difficult to obtain due to the lack of clarity of the diagnostic criteria. Although this case could be clinically classified as secondary racemose hemangioma of BA, the hemangioma was also considered to have developed from postoperative recurrent pneumonia, as previously discussed.

BAE has recently become a well-established, effective treatment for controlling recurrent or massive hemoptysis in patients with various pulmonary diseases[21]. Hayakawa et al[22] reported a high rate of hemoptysis control and high cumulative survival rate among patients with hemoptysis treated with BAE. However, Chun et al[1] reported that recurrent hemoptysis is not uncommon, occurring in 10%-55.3% of cases, although immediate control of hemoptysis is achieved in 73%-99% of treated patients. In addition, several authors have demonstrated that achieving embolization of ectopic BAs is more difficult than that of non-ectopic BAs, and that the complexity of performing selective and definite catheterization explains the increased risk of major complications observed in this patient population[7,23]. In the current case, BAE failed to control the patient’s hemoptysis due to incomplete embolization of several ectopic BAs, and surgical resection was eventually required. Although pulmonary resection for hemoptysis is known to carry an increased risk of death and morbidity due to pre-existing comorbidities and a poor respiratory reserve, particularly in the acute phase[19,24], we propose the use of early lobectomy soon after the patient’s hemodynamic parameters stabilize following failed BAE as a treatment option, even in cases of recurrent hemoptysis after esophagectomy. Furthermore, the use of lobectomy via VATS contributes to a shortened postoperative hospital stay due to the reduced invasiveness of the procedure in patients with poor respiratory function.

We recognize that our discussion includes various limitations. First, there was no evidence suggesting the precise mechanism of the ectopic/collateral BA development in this case. Second, we did not prove, in the resected specimen, that the hemoptysis was induced by rupture of one of the ectopic/collateral BAs, although we surmise that the ectopic BAs originating from the left subclavian artery were responsible based on the patient’s clinical course. However, we consider the patient’s bronchial bleeding and postoperative recurrent pneumonia to be associated because engorged BAs with medial hypertrophy and overgrowth of small branches were easily identified by histology as being localized near the bronchus and because postoperative recurrent pneumonia was persistently detected in the middle lobe.

In conclusion, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first case report of bronchial bleeding suspected to have derived from the ectopic/collateral bronchial arteries after radical esophagectomy with three-field lymphadenectomy for esophageal carcinoma. We propose the use of early lobectomy soon after the patient’s hemodynamic parameters stabilize following failed BAE as a treatment option, even in cases of recurrent hemoptysis after esophagectomy. We strongly believe that the present patient’s clinical course after esophagectomy for esophageal carcinoma is significant, particularly with respect to postoperative recurrent pneumonia due to bilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve injury.

The patient presented with sudden and recurrent hemoptysis 19 mo after esophagectomy.

The authors reported a rare case of bronchial bleeding suspected to have arisen from the ectopic/collateral bronchial arteries after radical esophagectomy for esophageal carcinoma with bilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve injury.

Locoregional recurrence and aorto-bronchial or gastro-tracheobronchial fistula formation should be considered as potential causes of bronchial bleeding after esophagectomy for esophageal carcinoma.

The hemoglobin level was 8.8 g/dL, and the C-reactive protein level was elevated to 16.1 mg/dL, whereas tumor markers, such as carcinoembryonic antigen, squamous cell carcinoma antigen, and carbohydrate antigen 19-9, were all within normal limits.

Bronchoscopy revealed a small level of hemosputum in the entrance of the right middle lobe bronchus, and contrast-enhanced computed tomography showed a tortuous artery ascending from the right inferior phrenic artery as well as several tortuous arteries arising from the left subclavian artery, which descended along the right main bronchus.

Organizing pneumonia with the accumulation of hemosiderin-laden macrophages was detected, and engorged bronchial artery (BA) with medial hypertrophy and overgrowth of small branches were noted near the bronchus.

Right middle lobectomy was performed via video-assisted thoracic surgery.

Chun et al demonstrated that chronic inflammation causes recruitment of a collateral blood supply from nonbronchial arteries. However, there are no other reports of bronchial bleeding suspected to arise from the ectopic/collateral bronchial arteries after esophagectomy with bilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve injury.

Middle lobe syndrome is characterized by chronic collapse of the middle lobe, which is more common in females; chronic productive cough and recurrent infections were the most common symptoms.

When encountering a patient with hemoptysis after esophagectomy, the possibility of bronchial bleeding from ectopic/collateral BAs must be considered, especially in cases of postoperative recurrent pneumonia due to bilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve injury.

This case report described the significant clinical course after esophagectomy for esophageal carcinoma. However, a limitation of the report is that there was no evidence indicating the precise mechanism for ectopic/collateral BA developments.

P- Reviewer: Chiarioni G, Marangoni G, Pal S S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Chun JY, Morgan R, Belli AM. Radiological management of hemoptysis: a comprehensive review of diagnostic imaging and bronchial arterial embolization. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2010;33:240-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Jean-Baptiste E. Clinical assessment and management of massive hemoptysis. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:1642-1647. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Li HP, Hsieh CC, Chiang HH, Wang TH, Lee JY, Huang MF, Chou SH. Aortobronchial fistula after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer -- a very rare complication. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2011;27:247-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Egan C, Szontagh-Kishazi P, Flavin R. Aortic fistula after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy and esophagectomy for esophageal carcinoma: an unusual cause of sudden death. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2012;33:270-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yasuda T, Sugimura K, Yamasaki M, Miyata H, Motoori M, Yano M, Shiozaki H, Mori M, Doki Y. Ten cases of gastro-tracheobronchial fistula: a serious complication after esophagectomy and reconstruction using posterior mediastinal gastric tube. Dis Esophagus. 2012;25:687-693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sahebazamani M, Rubio E, Boyd M. Airway gastric fistula after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. Ann Thorac Surg. 2012;93:988-990. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sancho C, Escalante E, Domínguez J, Vidal J, Lopez E, Valldeperas J, Montañá XJ. Embolization of bronchial arteries of anomalous origin. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1998;21:300-304. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Cauldwell EW, Siekert RG. The bronchial arteries; an anatomic study of 150 human cadavers. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1948;86:395-412. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Ferris EJ. Pulmonary hemorrhage. Vascular evaluation and interventional therapy. Chest. 1981;80:710-714. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Marshall TJ, Jackson JE. Vascular intervention in the thorax: bronchial artery embolization for haemoptysis. Eur Radiol. 1997;7:1221-1227. [PubMed] |

| 11. | McDonald DM. Angiogenesis and remodeling of airway vasculature in chronic inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:S39-S45. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Hartmann IJ, Remy-Jardin M, Menchini L, Teisseire A, Khalil C, Remy J. Ectopic origin of bronchial arteries: assessment with multidetector helical CT angiography. Eur Radiol. 2007;17:1943-1953. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Ponnuswamy I, Sankaravadivelu ST, Maduraimuthu P, Natarajan K, Sathyanathan BP, Sadras S. 64-detector row CT evaluation of bronchial and non-bronchial systemic arteries in life-threatening haemoptysis. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:e666-e672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Einarsson JT, Einarsson JG, Isaksson H, Gudbjartsson T, Gudmundsson G. Middle lobe syndrome: a nationwide study on clinicopathological features and surgical treatment. Clin Respir J. 2009;3:77-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gudbjartsson T, Gudmundsson G. Middle lobe syndrome: a review of clinicopathological features, diagnosis and treatment. Respiration. 2012;84:80-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Shaikhrezai K, Khorsandi M, Zamvar V. Middle lobe syndrome associated with major haemoptysis. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;8:84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Bertelsen S, Struve-Christensen E, Aasted A, Sparup J. Isolated middle lobe atelectasis: aetiology, pathogenesis, and treatment of the so-called middle lobe syndrome. Thorax. 1980;35:449-452. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Ayed AK. Resection of the right middle lobe and lingula in children for middle lobe/lingula syndrome. Chest. 2004;125:38-42. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Kimura M, Kuwabara Y, Ishiguro H, Takeyama H. Esophageal cancer with racemose hemangioma of the bronchial arteries. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;60:149-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Iwasaki M, Kobayashi H, Nomoto T, Arai T, Kondoh T. Primary racemose hemangioma of the bronchial artery. Intern Med. 2001;40:650-653. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Fernando HC, Stein M, Benfield JR, Link DP. Role of bronchial artery embolization in the management of hemoptysis. Arch Surg. 1998;133:862-866. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Hayakawa K, Tanaka F, Torizuka T, Mitsumori M, Okuno Y, Matsui A, Satoh Y, Fujiwara K, Misaki T. Bronchial artery embolization for hemoptysis: immediate and long-term results. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1992;15:154-158; discussion 158-159. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Rabkin JE, Astafjev VI, Gothman LN, Grigorjev YG. Transcatheter embolization in the management of pulmonary hemorrhage. Radiology. 1987;163:361-365. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Andréjak C, Parrot A, Bazelly B, Ancel PY, Djibré M, Khalil A, Grunenwald D, Fartoukh M. Surgical lung resection for severe hemoptysis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88:1556-1565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |