Published online Dec 14, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i46.17468

Revised: May 9, 2014

Accepted: July 24, 2014

Published online: December 14, 2014

Processing time: 323 Days and 22.1 Hours

AIM: To assess the rate of relapses of acute pancreatitis (AP), recurrent AP (RAP) and the evolution of endosonographic signs of chronic pancreatitis (CP) in patients with pancreas divisum (PDiv) and RAP.

METHODS: Over a five-year period, patients with PDiv and RAP prospectively enrolled were divided into two groups: (1) those with relapses of AP in the year before enrollment were assigned to have endoscopic therapy (recent RAP group); and (2) those free of recurrences were conservatively managed, unless they relapsed during follow-up (previous RAP group). All patients in both groups entered a follow-up protocol that included clinical and biochemical evaluation, pancreatic endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) every year and after every recurrence of AP, at the same time as endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).

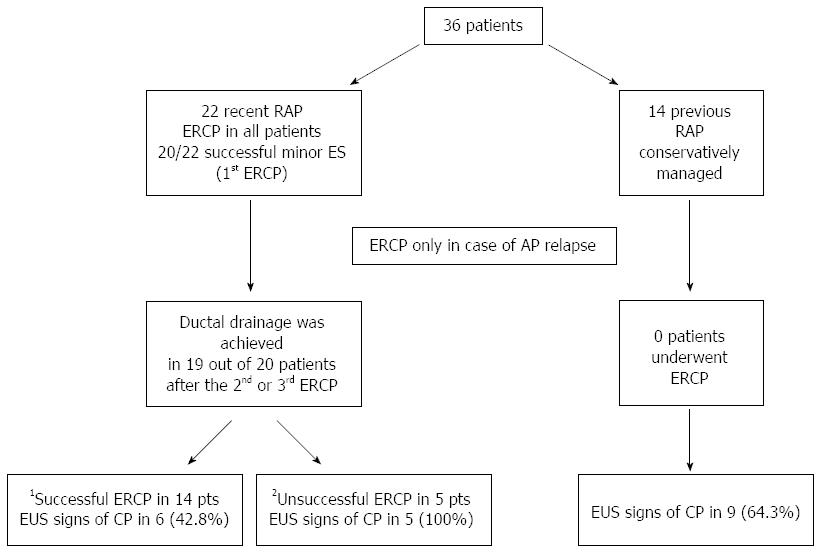

RESULTS: Twenty-two were treated by ERCP and 14 were conservatively managed during a mean follow-up of 4.5 ± 1.2 years. In the recent RAP group in whom dorsal duct drainage was achieved, AP still recurred in 11 (57.9%) after the first ERCP, in 6 after the second ERCP (31.6%) and in 5 after the third ERCP (26.3%). Overall, endotherapy was successful 73.7%. There were no cases of recurrences in the previous RAP group. EUS signs of CP developed in 57.9% of treated and 64.3% of untreated patients. EUS signs of CP occurred in 42.8% of patients whose ERCPs were successful and in all those in whom it was unsuccessful (P = 0.04). There were no significant differences in the rate of AP recurrences after endotherapy and in the prevalence of EUS signs suggesting CP when comparing patients with dilated and non-dilated dorsal pancreatic ducts within each group.

CONCLUSION: Patients with PDiv and recent episodes of AP can benefit from endoscopic therapy. Effective endotherapy may reduce the risk of developing EUS signs of CP at a rate similar to that seen in patients of previous RAP group, managed conservatively. However, in a subset of patients, endotherapy, although successful, did not prevent the evolution of endosonographic signs of CP.

Core tip: In this paper we compared the outcome of patients with pancreas divisum (PDiv) and recent or previous recurrent acute pancreatitis (RAP) after minor papilla endotherapy or observation, respectively. We confirmed previous findings regarding the benefit of endotherapy in patients with PDiv and RAP. In addition, we showed that effective endotherapy in patients with recent bouts of pancreatitis reduced the risk of developing endoscopic ultrasonography signs of chronic pancreatitis (CP) at a rate similar to that seen in patients without recent episodes of acute pancreatitis who are managed conservatively. However, in a subset of patients, endotherapy, although successful, did not prevent the evolution of endosonographic signs of CP.

- Citation: Mariani A, Di Leo M, Petrone MC, Arcidiacono PG, Giussani A, Zuppardo RA, Cavestro GM, Testoni PA. Outcome of endotherapy for pancreas divisum in patients with acute recurrent pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(46): 17468-17475

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i46/17468.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i46.17468

Pancreas divisum (PDiv) is the most common congenital variant of the pancreas, in which the ventral and dorsal ducts of the embryonic pancreas fail to fuse during organogenesis[1,2]. Less than 5% of people with PDiv have symptoms related to this altered anatomy[3,4]. However, the prevalence of PDiv amongst patients undergoing endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) for unexplained acute pancreatitis (AP) is much higher, up to 25.6%[5,6]. Several studies have found an increased prevalence of PDiv in patients with recurrent acute pancreatitis (RAP)[5,7-9]. A recent study based on magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) findings appeared to confirm that PDiv predisposes patients to RAP and chronic pancreatitis (CP)[4].

The mechanism responsible for the development of pain or AP in PDiv is unknown, but outflow obstruction of the pancreatic ductal system associated with stenosis or dysfunction of the minor papillary sphincter has been postulated[10-12]. Persisting outflow obstruction may lead to chronic damage to the gland. However, not all studies support the obstruction theory as the explanation for AP in PDiv[13] .

The goal of endoscopic therapy in PDiv patients is to open the minor sphincter to relieve presumed obstruction to pancreatic exocrine flow[13-15]. Although most published reports have been small case series, it has become clear that the RAP subset of PDiv patients is most likely to respond to endoscopic intervention, usually minor papillotomy[14-18]. However, it is still debated whether endoscopic minor sphincterotomy really improves the outcome and prevents progression to CP in these patients[19].

The aims of this prospective study were to assess the rate of relapses of CP and the evolution of morphological signs of CP in patients with PDiv and RAP.

According to the protocol approved by our institutional review board, all patients with PDiv suffering from RAP referred to our institution were scheduled to undergo routine MRCP with secretin stimulation (ss-MRCP), endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), genetic screening [specifically, for cystic fibrosis transmembrane regulator (CFTR) gene mutation], serum IgG-subclass 4 (IgG-4), and fecal elastase assays. Patients also had a medical consultation if they suffered a recurrence of AP. RAP was defined as two or more episodes of abdominal pain associated with serum amylase and/or lipase levels at least double the upper normal limit (110 IU/L for amylase, 90 IU/L for lipase) are present. AP was classified as mild or severe according to the Atlanta criteria[20].

Over a five-year period (from January, 2005, to December, 2009), all consecutive patients with a history of RAP, without signs suggesting CP on EUS investigation, and PDiv documented by ss-MRCP, were entered into a prospective follow-up study. Patients reporting at least one episode of AP in the year before enrollment were assigned to minor papilla sphincterotomy (recent RAP group), while those with no recurrences in the same period were assigned to observation, unless they relapsed during follow-up (previous RAP group). Patients in both groups had either a dilated or a non-dilated dorsal pancreatic duct. Amongst patients assigned to endotherapy, only those in whom dorsal duct drainage was achieved, were included in the per protocol analysis.

The following data were collected for each patient: age, sex, time of the first attack of AP, number of AP recurrences before and after enrollment, duration of the disease, duration of follow-up and time to development of CP. Patients were excluded for any of the following reasons: pancreatitis associated with known alcohol abuse (≥ 60 g of pure alcohol per day), gallstones, trauma, drug abuse, elevated serum IgG-4, hypertriglyceridemia or hypercalcemia; CFTR gene mutations; decreased fecal elastase activity; CP, known or suspected intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm or pancreatic cancer, family history of pancreatitis, pancreatic surgery and previous pancreatic sphincterotomy.

Informed consent for diagnostic procedures, blood sampling and data management for scientific purposes was routinely obtained from all patients.

The diagnosis of PDiv was established by MRCP when the dorsal pancreatic duct crossed the common bile duct to drain through the minor duodenal papilla, and was clearly separate from a smaller ventral duct[21]. The diameter of the main (dominant dorsal) pancreatic duct was considered dilated when its caliber was ≥ 3 mm. Ss-MRCP was performed in all patients to confirm the diagnosis of PDiv, to evaluate an abnormal pancreatic juice outflow through the minor papilla[22] and quantify pancreatic exocrine secretion.

ERCP procedures were done using a side-viewing duodenoscope (Pentax ED-3440T or ED3480TK or ED3680TK, Tokyo, Japan). The minor papilla was cannulated with a metal-tipped catheter (ERCP-1-Cremer, Cook Medical, Winston-Salem, NC, United States) or a pull-type sphincterotome (Mini-Tome MT-20M or Cannula-Tome II CT-20M, Cook Medical, Winston-Salem, NC, United States) which was used in all cases for sphincterotomy (minor papillotomy). Immediately after minor sphincterotomy, 5 French (Fr) gauge, single flanged, plastic pancreatic stents, 2-3 cm long, with a duodenal pigtail (SPSOF-5-3 Cook Medical, Winston-Salem, NC United States), or in some cases unflanged 5Fr stents (ZEPDS-5-2 Cook Medical, Winston-Salem, NC United States), were placed into the dorsal duct to prevent the development of post-ERCP pancreatitis. All patients received pharmacologic prophylaxis against post-ERCP pancreatitis using gabexate mesilate (Foy, Sanofi-Aventis, Milano, Italy)[23,24].

As with recurrences of AP, the Atlanta criteria were used to grade cases of post-ERCP pancreatitis[20]. All patients had plain abdominal X-rays approximately seven days after their pancreatic stent placement to verify its spontaneous migration into the duodenal lumen. Retained stents were removed using a duodenoscope at the earliest time available.

EUS procedures were performed using a linear-scanning echoendoscope (EG-3830UT, EG-3630U, FG-36UX; Pentax, Hamburg, Germany) at 5-10 MHz. EUS procedures were carried out by two experienced endosonographers (MCP, PGA, each with more than 500 EUS procedures/year). The endosonographers were blinded to the clinical findings at enrollment and to the other EUS examinations during follow-up. All pancreatic examinations were reviewed carefully by both endosonographers using the standard nine Wiersema criteria for diagnosing CP[25]. In the event of equivocal EUS findings they reached a consensus agreement. When four or more Wiersema criteria were present, the EUS findings were considered suggestive of chronic pancreatitis[26,27].

All patients in both groups entered a follow-up protocol that included: (1) clinical (abdominal pain) and biochemical evaluation including serum pancreatic enzyme levels and a surrogate marker for pancreatic exocrine function (fecal elastase: normal value > 200 μg/g; ScheBo Pancreatic Elastase 1 ELISA kit, ScheBo-Tech, Giessen, Germany); and (2) pancreatic EUS every year and after every recurrence of AP, at the same time as ERCP (i.e., under the same sedation).

Patients with a relapse of AP underwent minor papilla sphincterotomy (previous RAP group), or (recent RAP group) a second ERCP with: (1) extension of the previous papillary orifice (if judged inadequate because of difficulty or resistance to passage of a 3- to 5 Fr sphincterotome or catheter through the papillary orifice) and placement of a 7 Fr gauge, 3-7 cm long plastic pancreatic stent (SPSOF-7-3 to 7 or GPSO-7-3 to 7, Cook Medical, Winston-Salem, NC United States), scheduled to be left in place for one month and no longer (short-term stenting) to prevent post-procedural narrowing of the papillary opening and reduce the risk of long-term stent-induced pancreatic ductal changes; and (2) placement of a 7 Fr gauge, 3-7 cm long plastic pancreatic stent, scheduled to be left in place for three months then changed every three months for a year (long-term stenting) in cases not requiring extension of previous sphincterotomy.

When AP still recurred, a third ERCP was performed to place a 7 Fr gauge, 3-7 cm long stent if one was placed for only one month during the second procedure, or a 10 Fr gauge, 3-5 cm long stent (GEPD-10-3 or GEPD-10-5 Cook Medical, Winston-Salem, NC United States) if 7 Fr gauge long-term stenting had already been performed. The stent placed in the dorsal duct was scheduled to be left in place for three months, then changed every three months for a year.

Endotherapy was considered: (1) “successful” if there were no recurrences of AP; (2) “unsuccessful” if AP still recurred; and (3) “failed” if dorsal duct drainage was not achieved, including cannulation failure.

Mean ± SD were used for continuous variables, percentages for categorical variables. Groups were compared using the t-test or Mann Whitney test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. All differences were considered significant at a two-sided P value less than 0.05. Data were analyzed using the SPSS 17.0 system software (Chicago, IL, United States).

Thirty-six patients entered the protocol study, 22 in the recent RAP group and 14 in the previous RAP group. There were no differences between the two groups in sex, age, number of episodes of AP and duration of the disease before enrollment (Table 1).

| Previous RAP (14 pts) | Recent RAP (22 pts) | P value | |

| Male/female | 6/8 | 7/15 | 0.72 |

| Age (yr), mean ± SD | 52.0 ± 12.6 | 55.6 ± 10.4 | 0.35 |

| Episodes of pancreatitis (mean ± SD) | 2.8 ± 1.1 | 3.4 ± 1.2 | 0.14 |

| Duration of the disease (yr), mean ± SD | 3.6 ± 1.9 | 3.4 ± 1.5 | 0.73 |

In 18/36 patients (50%), ss-MRCP detected dilation of the dorsal pancreatic duct, 12 at baseline and 6 after secretin stimulation. Twelve of these patients were candidates for endotherapy (8 with dorsal duct dilatation at baseline and 4 after secretin) and 6 for observation (4 with dorsal duct dilatation at baseline and 2 after secretin). No morphologic or functional abnormalities of the dorsal pancreatic duct were seen on ss-MRCP in the other 18 patients, ten of whom underwent therapeutic ERCP.

Minor papilla cannulation and sphincterotomy was successful in 20 of the 22 patients (90.9%) who underwent ERCP. The two cases in which cannulation failed were not included in the per protocol analysis.

Thirty-three patients were followed up for a mean of 4.5 ± 1.2 years; range: 2.0-6.7), 19/20 in the recent RAP group and all 14 in the previous RAP group. One patient in whom the second ERCP failed (after initial successful dorsal duct drainage) refused a further ERCP and was lost to follow-up and for this reason excluded in the per protocol analysis.

The mean follow-up time did not significantly differ between treated (4.3 ± 1.3 years) and untreated patients (4.7 ± 1.1 years). In all patients undergoing endotherapy, the mean duration of stenting was 1.17 year (range: 1 mo-2 years). The mean duration of the follow-up after retrieval of the last stent was 2.7 years (range: 1.5-4 years).

In the 19 patients in whom dorsal duct drainage was achieved, AP still recurred in 11 (57.9%) after the first ERCP, in 6 after the second ERCP (31.6%) and in 5 after the third ERCP (26.3%). Overall, endotherapy was successful in 14 out of 19 patients (73.7%). There were no AP recurrences in the previous RAP group.

The five patients who still had further recurrences of AP after the third ERCP were followed-up by pancreatic EUS. One patient developed a pseudocyst and underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy. Except for this case, which was classified as severe AP, all the other relapses of pancreatitis were classified as mild disease.

Although the rate of AP recurrences after endotherapy was higher in patients without (37.5%) than in those with main pancreatic duct (MPD) dilatation (18.2%) at the time of enrollment, there was no statistically significant difference (P = 0.60) (Table 2).

Considering only the patients treated with long-term stenting, the recurrence rate of pancreatitis after retrieval of the last stent was 50% (5/10 patients).

A total of 58 ERCP procedures were carried out. Complications arose following fourteen of them (24.1%). Amongst the eight patients with major complications, seven developed mild AP (three after the first procedure) and one had bleeding. Minor complications were observed after six other procedures: pancreatic-type pain with normal serum amylase levels in three cases, and serum amylase levels more than three times the upper limit of normal without pain in the other three.

EUS investigation detected findings suggestive of CP in 20 of the 33 patients (60.6%) during follow-up, 11/19 (57.9%) amongst those in the recent RAP group and 9/14 (64.3%) in the previous RAP group (Figure 1): these rates were not significantly different. There were no significant differences in the prevalence of EUS signs suggesting CP when comparing patients with dilated and non-dilated dorsal pancreatic ducts within each group (Table 2). The mean duration of disease between the first attack of AP and the occurrence of EUS signs suggesting CP in the two groups was 6.1 ± 1.4 years ( and did not significantly differ between treated (5.7 ± 1.5) and untreated patients (6.4 ± 1.3).

In the 20 patients who developed EUS signs suggesting CP, the numbers (mean ± SD) of overall EUS criteria at enrolment (1.46 ± 0.52 vs 1.62 ± 0.74) and at the end of follow-up (4.46 ± 0.52 vs 4.25 ± 0.46) were not significantly different in the recent and previous RAP group, respectively. In each group, the number of EUS criteria detected at the end of follow-up was significantly higher (P < 0.001) than at enrollment; in all patients with EUS signs suggestive of CP, this increase was due to both ductal and parenchymal criteria. In these patients the most frequent EUS abnormalities were side branch dilation, hyperechoic MPD margins (ductal criteria), hyperechoic strands and foci (parenchymal criteria).

Amongst patients who underwent endotherapy, there were significantly fewer EUS signs of CP in the successful cases (6/14; 42.8%) than in the unsuccessful ones (5/5; 100%) (P = 0.04) (Table 3).

| Successful endotherapy1(14 pts) | Unsuccessful endotherapy2(5 pts) | P value | |

| Male/female | 11/3 | 4/1 | 1.0 |

| Age (yr), mean ± SD | 55.3 ± 7.9 | 55.0 ± 21.1 | 0.5 |

| No. of episodes of AP before study, yr, mean ± SD | 3.4 (1.3) | 3.4 (1.1) | 0.8 |

| Duration of ARP before enrollment (yr), mean ± SD | 3.2 (1.6) | 3.8 (1.3) | 0.3 |

| Duration of post-enrollment follow-up (yr), mean ± SD | 4.1 (1.3) | 4.8 (1.1) | 0.7 |

| EUS signs of CP | 6 (42.8) | 5 (100) | 0.04 |

| Duration of disease between the first attack of AP and the diagnosis of CP (yr), mean ± SD | 5.6 (1.3) | 6.1 (1.7) | 0.7 |

EUS signs of CP occurred less frequently after successful endotherapy in patients with recent RAP than in those with previous RAP which did not undergo to endotherapy (42.8% vs 64.3%), but the differences were not statistically significant (P = 0.45).

Table 4 shows the rate of EUS signs of CP in patients undergoing pancreatic stenting: this was higher in patients undergoing long-term stenting (80%) than those with no stent or only short-term stenting (33.3%) and similar to the observation group (64.3%).

Two patients developed reduced exocrine function, one in the previous RAP group, the other in the recent RAP group (whose ERCP was unsuccessful).

Although only a minority of patients with PDiv suffer life-long symptoms, this anatomical variant is found in up to 20% of patients with RAP[5,28,29]. It is not clear why these patients are at a higher risk for recurrent acute pancreatitis or whether their symptoms are etiologically related to PDiv[30]. In fact, genetic studies have suggested that as many as 10%-20% of patients with PDiv who have pancreatitis carry at least one allele of the CFTR gene product[31,32], or a higher frequency of SPINK1 gene mutation[33], compared with healthy controls, suggesting a multifactorial origin of pancreatitis in these cases.

The obstructive hypothesis has led in the last few years to symptomatic PDiv patients being treated by endoscopic minor papilla sphincterotomy and/or dorsal duct stenting[18,34], which has proved as effective as surgical sphincteroplasty, according to a recent systematic review[35].

As regards the efficacy of successful minor sphincterotomy, it is not known if lowering intra-ductal pressure affects the evolution of CP in these patients.

Our prospective follow-up study of patients with PDiv and RAP without signs of CP aimed to evaluate, over a mean period of 4.5 years, the clinical outcome in those who had or did not have bouts of acute pancreatitis in the year preceding the study after endoscopic therapy or observation, respectively. All patients with relapses of pancreatitis after the enrollment underwent endoscopic therapy. The study also investigated morphologic and functional changes suggesting CP during the follow-up. To our knowledge, this is the first study with these issues up to date.

The endoscopic therapy was successful in approximately 73% of cases, as reported in a recent review[35]. The relapses of acute pancreatitis in patients in whom endotherapy was unsuccessful could have had other unknown causes, possibly involving the pancreatic parenchyma rather than the ductal system, since we excluded any patients with alcohol abuse or with the CFTR-gene, but not SPINK 1-gene mutations.

EUS is recognized as the best imaging method to obtain high-resolution images of the pancreas. It can detect features of CP in the pancreatic parenchyma and ducts that are not visible by any other imaging modality including ERCP and pancreatic exocrine function tests[36,37]. EUS findings suggestive of CP, according to the Wiersema criteria[25], were seen during the follow-up in 57.9% patients undergone endoscopic therapy and 64.3% in the observation group.

Considering that the mean duration of symptoms before enrolment in the study was approximately 3.5 years, changes consistent with CP occurred in these patients after they had had the disease for six years; this agrees with a previous report[38].

Overall, the frequency of EUS signs of CP was similar in both groups of patients. Dorsal duct dilatation did not predict the EUS findings suggestive of CP in either group, confirming once again that factors other than ductal dilation may be involved in chronic disease in these patients. However, among patients assigned to endotherapy there were significantly fewer CP findings in those with successful compared to unsuccessful ERCP (42.8% vs 100%, P = 0.04). In cases where endotherapy was successful, there was a lower rate of EUS signs of CP (42.8%) than in the observation group (64.3%), although the difference was not statistically significant. Possibly we investigated two different categories of patients with PD and RAP: one with inactive disease, with a history of recurrent pancreatitis but no episodes in the year before the study, and another with persisting pancreatitis at the time of enrollment, as a consequence of a still active inflammatory process. In the latter group, the ductal drainage obtained by endotherapy may have reduced or at least delayed the evolution toward CP, compared with cases after unsuccessful therapy, and gave results similar to those in the observation group, confirming a possible role of the outflow obstruction in the occurrence of EUS signs suggesting CP. These data are in favor of a therapeutic endoscopic approach in patients with PDiv and a history of recent episodes of pancreatitis, independently of the dorsal ductal dilatation, but they need to be confirmed in further studies because of the small number of patients evaluated and the relatively limited follow-up after the last stent retrieval.

A major problem related to long-term pancreatic ductal stenting is the occurrence of stent-related ductal changes similar to those observed in CP, already reported in previous studies, especially in cases with non-dilated ducts[39-41].

In our series, despite the frequent use of small, short stents, some ductal changes consistent with CP may have been induced by the long-term stenting. In fact, findings suggesting CP developed during follow-up in 33.3% of patients submitted to minor papilla sphincterotomy without or with short-term stenting, a lower rate than in patients with long-term stenting (80%). However, considering only patients with successful long-term stenting, CP developed in a similar proportion (60%) of untreated patients (64.3%). We do not know whether the combination of ductal and parenchymal lesions suggesting CP observed with EUS in patients with unsuccessful endotherapy depends on the course of an existing undetectable chronic inflammatory process involving the gland, rather than the long-term stenting, or both. This possibility is supported by evidence that up to 53% of patients in studies with idiopathic pancreatitis and PD have an underlying CP[19,42]. In these patients, CP may be the cause rather than the consequence of unsuccessful endotherapy.

In conclusion, this prospective study showed that: (1) in most patients with PDiv suffering from recent repeated episodes of pancreatitis endoscopic ductal drainage had a beneficial symptomatic effect independent of whether there was dorsal duct dilatation; (2) about 60% of patients with either recent (after endotherapy) or previous (observation) episodes of acute pancreatitis developed EUS findings consistent with CP over a six-year period; and (3) patients with recent bouts of acute pancreatitis in whom endotherapy was successful had a significantly lower risk of developing EUS findings consistent with CP than those treated unsuccessfully, but further studies are needed to confirm these results.

Pancreas divisum (PDiv) is the most common anatomical congenital variant of pancreatic ductal system. Its role in recurrent acute pancreatitis (RAP) and in chronic pancreatitis (CP) remains controversial.

It is unclear if endoscopic therapy of pancreas divisum affects natural history of patients regarding the rate of recurrences and the evolution of CP.

It is the first study that evaluated endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) sign suggesting CP in patient with PDiv and RAP submitted endotherapy.

The results of the present study confirmed that successful endoscopic treatment of pancreas divisum in patients with recurrent acute pancreatitis could reduce the rate of recurrence and it could also reduce occurrence of EUS signs suggesting CP.

Recurrent was defined as two or more episodes of abdominal pain associated with serum amylase and/or lipase levels at least double the upper normal limit are present. Endotherapy was considered: (1) “successful” if there were no recurrences of AP; (2) “unsuccessful” if AP still recurred; and (3) “failed” if dorsal duct drainage was not achieved, including cannulation failure.

This paper has done a prospective study using EUS, but further studies are needed to confirm these results.

P- Reviewer: Chow WK, Kamisawa T, Pezzilli R S- Editor: Ma N L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Dawson W, Langman J. An anatomical-radiological study on the pancreatic duct pattern in man. Anat Rec. 1961;139:59-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Neuhaus H. Therapeutic pancreatic endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2002;34:54-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Delhaye M, Matos C, Arvanitakis M, Deviere J. Pancreatic ductal system obstruction and acute recurrent pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:1027-1033. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gonoi W, Akai H, Hagiwara K, Akahane M, Hayashi N, Maeda E, Yoshikawa T, Tada M, Uno K, Ohtsu H. Pancreas divisum as a predisposing factor for chronic and recurrent idiopathic pancreatitis: initial in vivo survey. Gut. 2011;60:1103-1108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bernard JP, Sahel J, Giovannini M, Sarles H. Pancreas divisum is a probable cause of acute pancreatitis: a report of 137 cases. Pancreas. 1990;5:248-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cotton PB. Congenital anomaly of pancreas divisum as cause of obstructive pain and pancreatitis. Gut. 1980;21:105-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 300] [Cited by in RCA: 259] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Richter JM, Schapiro RH, Mulley AG, Warshaw AL. Association of pancreas divisum and pancreatitis, and its treatment by sphincteroplasty of the accessory ampulla. Gastroenterology. 1981;81:1104-1110. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Sahel J, Cros RC, Bourry J, Sarles H. Clinico-pathological conditions associated with pancreas divisum. Digestion. 1982;23:1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Schnelldorfer T, Adams DB. Outcome after lateral pancreaticojejunostomy in patients with chronic pancreatitis associated with pancreas divisum. Am Surg. 2003;69:1041-104; discussion 1041-104;. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Bradley EL, Stephan RN. Accessory duct sphincteroplasty is preferred for long-term prevention of recurrent acute pancreatitis in patients with pancreas divisum. J Am Coll Surg. 1996;183:65-70. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Klein SD, Affronti JP. Pancreas divisum, an evidence-based review: part I, pathophysiology. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:419-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Warshaw AL, Simeone JF, Schapiro RH, Flavin-Warshaw B. Evaluation and treatment of the dominant dorsal duct syndrome (pancreas divisum redefined). Am J Surg. 1990;159:59-64; discussion 64-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Matos C, Metens T, Devière J, Delhaye M, Le Moine O, Cremer M. Pancreas divisum: evaluation with secretin-enhanced magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:728-733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Heyries L, Barthet M, Delvasto C, Zamora C, Bernard JP, Sahel J. Long-term results of endoscopic management of pancreas divisum with recurrent acute pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:376-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lans JI, Geenen JE, Johanson JF, Hogan WJ. Endoscopic therapy in patients with pancreas divisum and acute pancreatitis: a prospective, randomized, controlled clinical trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:430-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ertan A. Long-term results after endoscopic pancreatic stent placement without pancreatic papillotomy in acute recurrent pancreatitis due to pancreas divisum. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:9-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Jacob L, Geenen JE, Catalano MF, Johnson GK, Geenen DJ, Hogan WJ. Clinical presentation and short-term outcome of endoscopic therapy of patients with symptomatic incomplete pancreas divisum. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:53-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Borak GD, Romagnuolo J, Alsolaiman M, Holt EW, Cotton PB. Long-term clinical outcomes after endoscopic minor papilla therapy in symptomatic patients with pancreas divisum. Pancreas. 2009;38:903-906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Fogel EL, Toth TG, Lehman GA, DiMagno MJ, DiMagno EP. Does endoscopic therapy favorably affect the outcome of patients who have recurrent acute pancreatitis and pancreas divisum? Pancreas. 2007;34:21-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bradley EL. A clinically based classification system for acute pancreatitis. Summary of the International Symposium on Acute Pancreatitis, Atlanta, Ga, September 11 through 13, 1992. Arch Surg. 1993;128:586-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1929] [Cited by in RCA: 1736] [Article Influence: 54.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Bret PM, Reinhold C, Taourel P, Guibaud L, Atri M, Barkun AN. Pancreas divisum: evaluation with MR cholangiopancreatography. Radiology. 1996;199:99-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Mariani A, Curioni S, Zanello A, Passaretti S, Masci E, Rossi M, Del Maschio A, Testoni PA. Secretin MRCP and endoscopic pancreatic manometry in the evaluation of sphincter of Oddi function: a comparative pilot study in patients with idiopathic recurrent pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:847-852. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Testoni PA, Mariani A, Masci E, Curioni S. Frequency of post-ERCP pancreatitis in a single tertiary referral centre without and with routine prophylaxis with gabexate: a 6-year survey and cost-effectiveness analysis. Dig Liver Dis. 2006;38:588-595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Cavallini G, Tittobello A, Frulloni L, Masci E, Mariana A, Di Francesco V. Gabexate for the prevention of pancreatic damage related to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Gabexate in digestive endoscopy--Italian Group. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:919-923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 263] [Cited by in RCA: 252] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Wiersema MJ, Hawes RH, Lehman GA, Kochman ML, Sherman S, Kopecky KK. Prospective evaluation of endoscopic ultrasonography and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in patients with chronic abdominal pain of suspected pancreatic origin. Endoscopy. 1993;25:555-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 249] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Varadarajulu S, Eltoum I, Tamhane A, Eloubeidi MA. Histopathologic correlates of noncalcific chronic pancreatitis by EUS: a prospective tissue characterization study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:501-509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Zimmermann MJ, Mishra G, Lewin DN, Hawes RH, Coyle W, Adams DA, Hoffman B. Comparison of EUS findings with histopathology in chronic pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:AB185. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 28. | Venu RP, Geenen JE, Hogan W, Stone J, Johnson GK, Soergel K. Idiopathic recurrent pancreatitis. An approach to diagnosis and treatment. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34:56-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Levy MJ, Geenen JE. Idiopathic acute recurrent pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2540-2555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Lehman GA, Sherman S. Pancreas divisum. Diagnosis, clinical significance, and management alternatives. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1995;5:145-170. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Gelrud A, Sheth S, Banerjee S, Weed D, Shea J, Chuttani R, Howell DA, Telford JJ, Carr-Locke DL, Regan MM. Analysis of cystic fibrosis gener product (CFTR) function in patients with pancreas divisum and recurrent acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1557-1562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Bertin C, Pelletier AL, Vullierme MP, Bienvenu T, Rebours V, Hentic O, Maire F, Hammel P, Vilgrain V, Ruszniewski P. Pancreas divisum is not a cause of pancreatitis by itself but acts as a partner of genetic mutations. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:311-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Garg PK, Khajuria R, Kabra M, Shastri SS. Association of SPINK1 gene mutation and CFTR gene polymorphisms in patients with pancreas divisum presenting with idiopathic pancreatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:848-852. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Chacko LN, Chen YK, Shah RJ. Clinical outcomes and nonendoscopic interventions after minor papilla endotherapy in patients with symptomatic pancreas divisum. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:667-673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Liao Z, Gao R, Wang W, Ye Z, Lai XW, Wang XT, Hu LH, Li ZS. A systematic review on endoscopic detection rate, endotherapy, and surgery for pancreas divisum. Endoscopy. 2009;41:439-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Sahai AV, Zimmerman M, Aabakken L, Tarnasky PR, Cunningham JT, van Velse A, Hawes RH, Hoffman BJ. Prospective assessment of the ability of endoscopic ultrasound to diagnose, exclude, or establish the severity of chronic pancreatitis found by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:18-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Catalano MF, Lahoti S, Geenen JE, Hogan WJ. Prospective evaluation of endoscopic ultrasonography, endoscopic retrograde pancreatography, and secretin test in the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:11-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 235] [Cited by in RCA: 208] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Frulloni L, Castellani C, Bovo P, Vaona B, Calore B, Liani C, Mastella G, Cavallini G. Natural history of pancreatitis associated with cystic fibrosis gene mutations. Dig Liver Dis. 2003;35:179-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Kozarek RA. Pancreatic stents can induce ductal changes consistent with chronic pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:93-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 245] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Rashdan A, Fogel EL, McHenry L, Sherman S, Temkit M, Lehman GA. Improved stent characteristics for prophylaxis of post-ERCP pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:322-329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Smith MT, Sherman S, Ikenberry SO, Hawes RH, Lehman GA. Alterations in pancreatic ductal morphology following polyethylene pancreatic stent therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:268-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | DiMagno MJ, Wamsteker EJ. Pancreas divisum. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2011;13:150-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |