Published online Nov 21, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i43.16372

Revised: July 7, 2014

Accepted: August 13, 2014

Published online: November 21, 2014

Processing time: 257 Days and 13.3 Hours

Hepatic actinomycosis is rare, with few published cases. There are no characteristic clinical manifestations, and computed tomography (CT) shows mainly low-density images, making clinical diagnosis difficult, and leading to frequent misdiagnosis as primary liver cancer, metastatic liver cancer or liver abscess. Diagnosis normally requires examination of both the aetiology and pathology. This article reports one male patient aged 55 who was hospitalized because of repeated upper abdominal pain for more than 2 mo. He exhibited no chills, fever or yellow staining of the skin and sclera, and examination revealed no positive signs. The routine blood results were: haemoglobin 110 g/L, normal numbers of leukocytes and neutral leukocytes, serum albumin 32 g/L, negative serum hepatitis B markers and hepatitis C antibodies, normal tumour markers (alpha-fetoprotein and carcinoembryonic antigen). An abdominal CT scan revealed an 11.2 cm × 5.8 cm × 7.4 cm mass with an unclear edge in the left liver lobe. The patient was diagnosed as having primary liver cancer, and left lobe resection was performed. The postoperative pathological examination found multifocal actinomycetes in the hepatic parenchyma, which was accompanied by chronic suppurative inflammation. A focal abscess had formed, and large doses of sodium penicillin were administered postoperatively as anti-infective therapy. This article also reviews 32 cases reported in the English literature, with the aim of determining the clinical features and treatment characteristics of this disease, and providing a reference for its diagnosis and treatment.

Core tip: Actinomycetes are Gram-positive anaerobic bacteria. Hepatic actinomycosis is very rare, with no specific clinical manifestations or imaging features. The clinical diagnosis of hepatic actinomycosis is difficult, and the rate of misdiagnosis is high. It is often misdiagnosed as malignant liver tumour. This paper reports one case of recently diagnosed and treated hepatic actinomycosis, and reviews 32 previously confirmed hepatic actinomycosis cases. The clinical characteristics and diagnosis of hepatic actinomycosis are analysed, providing a reference for the diagnosis and treatment of this disease.

- Citation: Yang XX, Lin JM, Xu KJ, Wang SQ, Luo TT, Geng XX, Huang RG, Jiang N. Hepatic actinomycosis: Report of one case and analysis of 32 previously reported cases. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(43): 16372-16376

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i43/16372.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i43.16372

Actinomycosis is a chronic, granulomatous and suppurative disease caused by infection with actinomycetes[1,2]. These organisms are part of the normal flora existing in the human pharynx oralis, gastrointestinal tract and female reproductive tract, have low pathogenicity, and normally cause infections in the facial area, chest, abdominal and pelvic cavities[1,3]. Abdominal actinomycotic diseases include abdomen and intrauterine devices (IUD)-related pelvic abscesses, and infections of the appendix, anus, rectum and liver[4]. Hepatic actinomycosis (HA) is very rare, and is often a secondary infection. If no primary lesion is found, it might be considered a primary or isolated HA, but with non-specific clinical manifestations and radiographic changes, the clinical diagnosis is difficult, often resulting in delayed diagnosis and treatment[2]. This paper reports one case of recently diagnosed and treated HA, and reviews 32 confirmed cases of HA in the English literature, aiming to provide a reference for the diagnosis and treatment of HA.

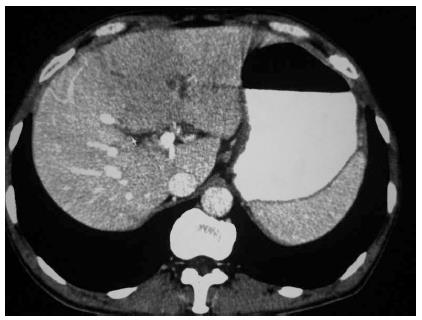

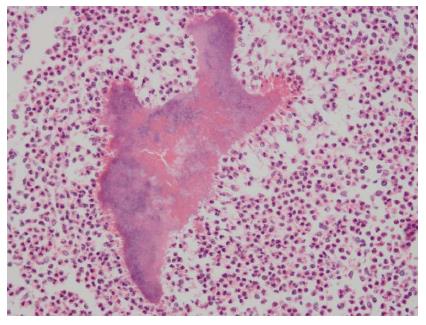

A 55-year-old male was hospitalized as a result of repeated upper abdominal pain lasting more than 2 mo. There was no evidence of radioactive pain, chills, fever, nausea, vomiting, abdominal distension, diarrhoea, yellow staining of the skin and sclera, or gum bleeding. The patient had been administered infusion therapy at a local hospital for two weeks (the specific drug was unclear), without significant improvement. Since onset, his mood, appetite, sleeping habits, stools and urine had remained unchanged, but he had lost about 10 kg. The patient denied a past history of eating raw meat, trauma, or blood transfusion. The patient occasionally drank a small amount of alcohol, and until 4 mo previously, had smoked 10 cigarettes/d for 20 years. The physical examination revealed: temperature 36.5 °C, pulse 98 beats/min, respiration 20 times/min, blood pressure 119/82 mmHg. The patient’s mood was normal, the skin and sclera were not yellow, and there were no petechiae, liver palms or spider veins. The general superficial lymph nodes were not palpable or enlarged. The sounds of lung breathing were clear, without obvious dry or wet rales in either lung, the heart was not enlarged, the heart rate was regular at 98 beats/min and no pathological murmurs were heard. The abdomen was soft, with mild epigastric tenderness, but without rebound tenderness or muscle tension; the murphy sign was negative, the liver and spleen were not palpable, and there was no sensitivity to percussion in the hepatonephric area; the excursive sonant was (-), and the lower extremities had no oedema. Routine blood tests revealed that the haemoglobin was 110 g/L, the total numbers of leukocytes and neutral leukocytes were normal, the serum albumin was 32 g/L, and other parameters were normal. The hepatitis B markers and hepatitis C antibodies were negative and the tumour markers (alpha-fetoprotein and carcinoembryonic antigen) were normal. An abdominal computed tomography (CT, SIEMENS somatom sensation 16, Germany) scan showed an approximately 11.2 cm × 5.8 cm × 7.4 cm mass with an unclear edge in the left hepatic lobe, which involved II, SII, SIII and SIV. Abnormal blood vessels could be seen in the arterial phase, with regurgitation and mild enhancement of the arteries; the portal vein was more clearly visible, and thus there was considered to be a high possibility of neoplastic lesions. The hepatogastric ligaments and the para-abdominal aorta lymph nodes were enlarged and metastasized (Figure 1). The clinical diagnosis indicated primary liver cancer, and therefore left lobe resection was performed. The postoperative pathological examination revealed multifocal actinomycetes in the hepatic parenchyma, accompanied by chronic suppurative inflammation, and a focal abscess. The peripheral fibrous tissues and bile ducts showed hyperplasia, the vessels were dilated, and the liver cells partially denatured, accompanied by chronic inflammatory cell infiltration in the portal area (pathological staining reagents: hexamethylenetetramine, sodium tetraborate and crystal violet were purchased from Chengdu Kelong Chemical Reagents, and basic fuchsin was purchased from Shanghai 3rd Reagent Industry, Figure 2).

The patient was administered sodium penicillin 4000000 units iv.gtt q6h postoperatively. Thirteen days later the patient had improved and was discharged. The patient continued treatment with sodium penicillin 4000000 units iv.gtt q6h at a local hospital. One month later, the patient had no discomfort, and abdominal CT revealed that most of the left liver was missing. The left branch of the portal vein was not visible, and there was a low-density cystic mass shadow in the left hepatic surgical area, with a maximum layer diameter of about 5.8 cm and water density. The boundary was clear, and the right liver lobe was displaced and deformed. Punctiform gas could be seen at the front edge of the conglomerate shadow, high-density puncto-striatus shadows could be seen at some edges, while the front fat gap was fuzzy, possibly due to changes in encapsulated fluid.

Twenty-eight case reports with complete data of HA from 1996 to 2012 were retrieved from Medline[2,5-30], which in total reported 32 cases.

Clinical features of HA: Among the 32 HA patients identified, the youngest was 5 years old, while the oldest was 86 years old. Most were male. Onset was chronic or subacute, with the shortest duration being 3 d, and the longest 1 year; the average duration was 82.3 ± 96.6 days. Most patients had complications, among which the most common was a previous history of abdominal surgery, especially gastrointestinal surgery and gynaecological surgery, followed by diabetes, oral diseases and the use of IUD. Among these patients, 92.6% reported fever, 60% reported weight loss, 70.8% had anaemia, and 93.1% showed increased numbers of peripheral blood leukocytes and/or neutrophils, as shown in Table 1. Seventy-five percent (24/32) of patients had a secondary HA infection in the lungs, chest, pelvic and abdominal organs, etc., while the original HA infection was confined to the liver (Table 1).

| Age (yr) | 45.5 ± 21.12 (5-86) |

| Gender (male/female) | 19/13 |

| Duration (d) | 82.3 ± 96.6 (3-365) |

| Median (d) | 37.5 |

| Combined diseases | 191 (59.4) |

| Diabetics | 5 (15.6) |

| Previous history of abdominal surgery and trauma2 | 9 (28.1) |

| Pancreatitis | 3 (9.4) |

| Oral diseases | 3 (9.4) |

| IUD | 2 (6.3) |

| Drinking | 1 (3.1) |

| Asthma | 1 (3.1) |

| Gastroesophageal Reflux | 1 (3.1) |

| Diverticulitis | 1 (3.1) |

| Chickenpox | 1 (3.1) |

| Fever | 25/27 (92.6) |

| Weight loss | 15/25 (60.0) |

| Anemia | 17/24 (70.8) |

| Peripheral blood WBC and/or neutralization increased | 27/29 (93.1) |

| Diagnostic methods | |

| Liver puncture fluid | 19/32 (59.4) |

| Liver puncture biopsy | 4/32 (12.5) |

| Liver lobe resection | 6/32 (18.7) |

| Others (fiberscopic lung biopsy, pleura biopsy and ovariotomy, 1 case each) | |

| 3/32 (9.45) | |

| Misdiagnosed | |

| Liver malignant tumor | 20/28 (71.4) |

| Hepatophyta | 8/28 (28.6) |

| Liver hydatidosis | 2/28 (7.1) |

| Others3 | 2/28 (7.1) |

| Treatments | |

| Surgery or puncture drainage + anti-infection | 12/32 (37.5) |

| Liver lobe resection + anti-infection | 6/32 (18.7) |

| Anti-infection alone | 14/32 (43.8) |

Imaging features of HA: The imaging features of HA were mainly low-density changes (68.8% of cases), making it easily misdiagnosed as primary liver cancer and metastatic liver cancer; 18.7% exhibited abscess-like changes, which would be difficult to differentiate from acute bacterial liver abscess; in addition, a few exhibited cystic, mass-like and nodular changes. A single lesion was found in 72.4% of patients, and the right liver lobe was the most common site of infection, with a cumulative involvement rate of 93.1%. The imaging characteristics of HA are shown in Table 2.

| Imaging characteristic (cases) | n (%) |

| Imaging characteristics (32) | |

| Low density | 22 (68.8) |

| Abscess-like | 6 (18.7) |

| Cystic | 2 (6.3) |

| Mass-like and nodular | 2 (6.3) |

| Lesion numbers (29) | |

| Single | 21 (72.4) |

| Multiple | 8 (27.6) |

| Lesion distribution (29) | |

| Liver right lobe | 19 (65.5) |

| Liver left lobe | 2 (6.9) |

| Liver right and left lobes | 8 (27.6) |

Diagnosis of HA: The diagnosis of HA depends on the clinical manifestations and imaging findings, and thus it is easily misdiagnosed as a malignant tumour or acute bacterial liver abscess. None of the 32 patients was diagnosed simply according to clinical manifestations and radiographic changes. Other diagnostic methods included ultrasound or CT-guided liver puncture drainage, liver puncture biopsy and liver surgical biopsy for pathological and aetiological examinations (Table 2). The final diagnosis relies on the histopathology and aetiology. The pathological examination may find specific sulphur granules, and Gram staining may find filamentous Gram-positive bacteria; however, the positive rate of actinomycetes in pus and tissue fluid cultivation is normally only 50%, and therefore cultivation should not be relied upon by itself, but should be combined with histopathological examination and smear Gram staining. The pathological and aetiological features of HA are presented in Table 3.

| Diagnostic method (cases) | n (%) |

| Histodiagnosis (31) | |

| Sulfur granules | 22 (71.0) |

| Etiological diagnosis | |

| Gram staining (27) | 22 (81.5) |

| Cultivation (20) | |

| Actinomyces | 10 (50.0) |

| Other bacteria | 3 (15) |

| Mixed infection | 4 (20) |

Treatment of HA: Treatment of HA mainly involves surgical drainage or puncture drainage, hepatic resection, and postoperative anti-infection treatment with anti-infectives such as penicillin, amoxicillin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, ampicillin, clindamycin and minocycline for 3-12 mo[2,6-31]; and outcome is usually satisfactory.

The actinomyces are Gram-positive anaerobic bacteria, and actinomycosis has been recognized for more than 150 years. It is mainly caused by Actinomyces israelii. As the clinical manifestations are diverse, with slow disease progression and a low incidence, diagnosis is difficult, and misdiagnosis is common[31]. The pathological manifestations are chronic suppurative changes, resulting in multiple small abscesses in the liver. Actinomyces are part of the normal flora in the oropharynx, gastrointestinal tract and female reproductive tract, and can cause infections in various body parts, such as the chest, abdomen, pelvis and central nervous system. HA is often a secondary infection following abdominal infection, and primary HA is rare. HA accounts for 15% of abdominal actinomycosis, and 5% of all actinomycosis. However, the preoperative diagnosis rate is less than < 10%, and it is difficult to distinguish from HCC and liver abscess radiologically[6].

On CT, HA is mainly seen as single or multiple low-density shadows, which might be accompanied by the enhancement; the border is often unclear, and it is easy to confuse HA with primary hepatocellular carcinoma and metastatic liver cancer. HA sometimes produces abscess-like and cyst-like changes, and thus is often misdiagnosed as liver abscess and liver hydatid disease. Thus, the imaging diagnosis alone is insufficient to make a correct diagnosis. The diagnosis is mainly based on percutaneous biopsy or pathological biopsy after surgical resection, while abscess-like or cystic-like changes on imaging would require the examination of drainage fluid. The smear diagnostic methods include Gram staining, cultivation and the pathological finding of sulphur particles.

Although HA is a chronic suppurative infection, in the absence of active treatment, patients may experience systemic failure, multiple-organ failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation and other life-threatening sequelae. Penicillin is the first choice of antimicrobial therapy, and amoxicillin, chloramphenicol, erythromycin, clindamycin, tetracycline and doxycycline are also effective. HA is resistant to the following drugs: fluoroquinolones, aztreonam, aminoglycosides (except for streptomycin), fosfomycin (in vitro susceptibility test). Antibiotics should be administered for 3 mo or more, and even up to 12 mo. After proactive, timely and effective antimicrobial therapy, the prognosis is good. In patients who exhibit abscess or cyst-like changes, ultrasound or CT-guided percutaneous drainage or surgical drainage might be performed. For patients who exhibit low-density changes on imaging, surgical resection is an important method of treatment if anti-infective therapy is not effective.

A 55-year-old male patient was hospitalized as a result of repeated upper abdominal pain lasting more than 2 mo. There was no evidence of radioactive pain, chills, fever, nausea, vomiting, abdominal distension, diarrhoea, yellow staining of the skin and sclera, or gum bleeding.

The physical examination revealed: temperature 36.5 °C, pulse 98 beats/min, respiration 20 times/min, blood pressure 119/82 mmHg.

Routine blood tests revealed that the haemoglobin was 110 g/L, the total numbers of leukocytes and neutral leukocytes were normal, the serum albumin was 32 g/L, and other parameters were normal. The hepatitis B markers and hepatitis C antibodies were negative and the tumour markers (alpha-fetoprotein and carcinoembryonic antigen) were normal.

An abdominal computed tomography (CT, SIEMENS somatom sensation 16, Germany) scan showed an approximately 11.2 cm × 5.8 cm × 7.4 cm mass with an unclear edge in the left hepatic lobe, which involved II, SII, SIII and SIV.

The peripheral fibrous tissues and bile ducts showed hyperplasia, the vessels were dilated, and the liver cells partially denatured, accompanied by chronic inflammatory cell infiltration in the portal area.

The patient was administered sodium penicillin 4000000 units iv.gtt q6h postoperatively. Thirteen days later the patient had improved and was discharged. The patient continued treatment with sodium penicillin 4000000 units iv.gtt q6h at a local hospital.

In this study, the authors investigated the clinical characteristics and diagnosis of hepatic actinomycosis. This will increase our understanding of hepatic actinomycosis and reduce the misdiagnosis rate.

P- Reviewer: Kasano Y S- Editor: Wang JL L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Wong JJ, Kinney TB, Miller FJ, Rivera-Sanfeliz G. Hepatic actinomycotic abscesses: diagnosis and management. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;186:174-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kim YS, Lee BY, Jung MH. Metastatic hepatic actinomycosis masquerading as distant metastases of ovarian cancer. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2012;38:601-604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Brook I. Actinomycosis: diagnosis and management. South Med J. 2008;101:1019-1023. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wang HK, Sheng WH, Hung CC, Chen YC, Liew PL, Hsiao CH, Chang SC. Hepatosplenic actinomycosis in an immunocompetent patient. J Formos Med Assoc. 2012;111:228-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kasano Y, Tanimura H, Yamaue H, Hayashido M, Umano Y. Hepatic actinomycosis infiltrating the diaphragm and right lung. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:2418-2420. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Sugano S, Matuda T, Suzuki T, Makino H, Iinuma M, Ishii K, Ohe K, Mogami K. Hepatic actinomycosis: case report and review of the literature in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 1997;32:672-676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sharma M, Briski LE, Khatib R. Hepatic actinomycosis: an overview of salient features and outcome of therapy. Scand J Infect Dis. 2002;34:386-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mukundan G, Fishman EK. Pulmonary and hepatic actinomycosis: atypical radiologic findings of an uncommon infection. Clin Imaging. 2000;24:78-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Felekouras E, Menenakos C, Griniatsos J, Deladetsima I, Kalaxanisi N, Nikiteas N, Papalambros E, Kordossis T, Bastounis E. Liver resection in cases of isolated hepatic actinomycosis: case report and review of the literature. Scand J Infect Dis. 2004;36:535-538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lakshmana Kumar YC, Javherani R, Malini A, Prasad SR. Primary hepatic actinomycosis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2005;99:868-870. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Schmeding M, Neumann U, Neuhaus P. [Solid actinomycosis of the liver]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2005;130:2705-2707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lange CM, Hofmann WP, Kriener S, Jacobi V, Welsch C, Just-Nuebling G, Zeuzem S. Primary actinomycosis of the liver mimicking malignancy. Z Gastroenterol. 2009;47:1062-1064. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Culafić DM, Lekić NS, Kerkez MD, Mijac DD. Liver actinomycosis mimicking liver tumour. Vojnosanit Pregl. 2009;66:924-927. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lall T, Shehab TM, Valenstein P. Isolated hepatic actinomycosis: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2010;4:45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kanellopoulou T, Alexopoulou A, Tiniakos D, Koskinas J, Archimandritis AJ. Primary hepatic actinomycosis mimicking metastatic liver tumor. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:458-459. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Cetinkaya Z, Kocakoc E, Coskun S, Ozercan IH. Primary hepatic actinomycosis. Med Princ Pract. 2010;19:196-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wayne MG, Narang R, Chauhdry A, Steele J. Hepatic actinomycosis mimicking an isolated tumor recurrence. World J Surg Oncol. 2011;9:70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Llenas-García J, Lalueza-Blanco A, Fernández-Ruiz M, Villar-Silva J, Ochoa M, Lozano F, Lizasoain M, Aguado JM. Primary hepatic actinomycosis presenting as purulent pericarditis with cardiac tamponade. Infection. 2012;40:339-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Min KW, Paik SS, Han H, Jang KS. Education and Imaging. Hepatobiliary and pancreatic: Hepatic actinomycosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Rakotoson JL, Andrianasolo R, Rakotomizao JR, Rakotoharivelo H, Andrianarisoa AC. [Disseminated pulmonary actinomycosis with hepatic injury: a misleading form mimicking a polymetastatic picture]. Rev Pneumol Clin. 2012;68:40-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Guven A, Kesik V, Deveci MS, Ugurel MS, Ozturk H, Koseoglu V. Post varicella hepatic actinomycosis in a 5-year-old girl mimicking acute abdomen. Eur J Pediatr. 2008;167:1199-1201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lin TP, Fu LS, Peng HC, Lee T, Chen JT, Chi CS. Intra-abdominal actinomycosis with hepatic pseudotumor and xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis in a 6-y-old boy. Scand J Infect Dis. 2001;33:551-553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hilfiker ML. Disseminated actinomycosis presenting as a renal tumor with metastases. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:1577-1578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Harsch IA, Benninger J, Niedobitek G, Schindler G, Schneider HT, Hahn EG, Nusko G. Abdominal actinomycosis: complication of endoscopic stenting in chronic pancreatitis? Endoscopy. 2001;33:1065-1069. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lai AT, Lam CM, Ng KK, Yeung C, Ho WL, Poon LT, Ng IO. Hepatic actinomycosis presenting as a liver tumour: case report and literature review. Asian J Surg. 2004;27:345-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lawson E. Systemic actinomycosis mimicking pelvic malignancy with pulmonary metastases. Can Respir J. 2005;12:153-154. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Islam T, Athar MN, Athar MK, Usman MH, Misbah B. Hepatic actinomycosis with infiltration of the diaphragm and right lung: a case report. Can Respir J. 2005;12:336-337. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Kocabay G, Cagatay A, Eraksoy H, Tiryaki B, Alper A, Calangu S. A case of isolated hepatic actinomycosis causing right pulmonary empyema. Chin Med J (Engl). 2006;119:1133-1135. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Kim HS, Park NH, Park KA, Kang SB. A case of pelvic actinomycosis with hepatic actinomycotic pseudotumor. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2007;64:95-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | O’Kelly K, Abu J, Hammond R, Jensen M, O’Connor RA, Soomro I. Pelvic actinomycosis with secondary liver abscess, an unusual presentation. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012;163:239-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Kanellopoulou T, Alexopoulou A, Tanouli MI, Tiniakos D, Giannopoulos D, Koskinas J, Archimandritis AJ. Primary hepatic actinomycosis. Am J Med Sci. 2010;339:362-365. [PubMed] |