Published online May 7, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i17.5017

Revised: December 31, 2013

Accepted: March 5, 2014

Published online: May 7, 2014

Processing time: 207 Days and 16.3 Hours

AIM: To investigate whether routinely measured clinical variables could aid in differentiating intestinal tuberculosis (ITB) from Crohn’s disease (CD).

METHODS: ITB and CD patients were prospectively included at four South Indian medical centres from October 2009 to July 2012. Routine investigations included case history, physical examination, blood biochemistry, ileocolonoscopy and histopathological examination of biopsies. Patients were followed-up after 2 and 6 mo of treatment. The diagnosis of ITB or CD was re-evaluated after 2 mo of antituberculous chemotherapy or immune suppressive therapy respectively, based on improvement in signs, symptoms and laboratory variables. This study was considered to be an exploratory analysis. Clinical, endoscopic and histopathological features recorded at the time of inclusion were subject to univariate analyses. Disease variables with sufficient number of recordings and P < 0.05 were entered into logistic regression models, adjusted for known confounders. Finally, we calculated the odds ratios with respective confidence intervals for variables associated with either ITB or CD.

RESULTS: This study included 38 ITB and 37 CD patients. Overall, ITB patients had the lowest body mass index (19.6 vs 22.7, P = 0.01) and more commonly reported weight loss (73% vs 38%, P < 0.01), watery diarrhoea (64% vs 33%, P = 0.01) and rural domicile (58% vs 35%, P < 0.05). Endoscopy typically showed mucosal nodularity (17/31 vs 2/37, P < 0.01) and histopathology more frequently showed granulomas (10/30 vs 2/35, P < 0.01). The CD patients more frequently reported malaise (87% vs 64%, P = 0.03), nausea (84% vs 56%, P = 0.01), pain in the right lower abdominal quadrant on examination (90% vs 54%, P < 0.01) and urban domicile (65% vs 42%, P < 0.05). In CD, endoscopy typically showed involvement of multiple intestinal segments (27/37 vs 9/31, P < 0.01). Using logistic regression analysis we found weight loss and nodularity of the mucosa were independently associated with ITB, with adjusted odds ratios of 8.6 (95%CI: 2.1-35.6) and 18.9 (95%CI: 3.5-102.8) respectively. Right lower abdominal quadrant pain on examination and involvement of ≥ 3 intestinal segments were independently associated with CD with adjusted odds ratios of 10.1 (95%CI: 2.0-51.3) and 5.9 (95%CI: 1.7-20.6), respectively.

CONCLUSION: Weight loss and mucosal nodularity were associated with ITB. Abdominal pain and excessive intestinal involvement were associated with CD. ITB and CD were equally common.

Core tip: Intestinal tuberculosis (ITB) and Crohn’s disease (CD) may easily be confused with one another in terms of clinical, laboratory, endoscopic and histopathological features. In this prospective multi-centre study from Southern India, we found weight loss and mucosal nodularity were associated with ITB. Furthermore, right lower abdominal pain and multi-segment intestinal involvement were associated with CD. The random inclusion of as many CD as ITB patients suggests that CD may be increasing in the region. Current diagnostic modalities for differentiating ITB from CD are imperfect and simple inexpensive tools for diagnosis are needed.

- Citation: Larsson G, Shenoy T, Ramasubramanian R, Balakumaran LK, Småstuen MC, Bjune GA, Moum BA. Routine diagnosis of intestinal tuberculosis and Crohn's disease in Southern India. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(17): 5017-5024

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i17/5017.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i17.5017

Intestinal tuberculosis (ITB) is commonly encountered by gastroenterologists in India, and is presumably seen more often than Crohn’s disease (CD)[1-3]. Nevertheless, CD seems to be increasing in the area, as in other regions of improved hygiene, sanitation and health care[4].

The presentation and pathologic findings in ITB may vary, be non-specific and can easily be confounded with other abdominal or gastrointestinal diseases such as CD or ulcerative colitis[5]. CD is most commonly mistaken for ITB, because the clinical appearance and the radiological, endoscopic and histopathological manifestations may be identical[2,6]. This poses diagnostic problems due to the lack of awareness and the difficulty of confirming TB by bacteriological methods[7]. Skilled clinicians may make the correct diagnosis in approximately half of the patients based on medical history, clinical signs and symptoms alone. By adding results of radiological, endoscopic, histopathological and microbiological investigations, the correct diagnosis may be achieved in up to 80% of the patients[8].

Failing to diagnose ITB represents a considerable risk of morbidity and mortality. However, misdiagnosing and treating ITB as CD could potentially be lethal given the immunosuppressive nature of CD therapy. Conversely, empiric antituberculous chemotherapy (ATT) may complicate diagnosis of ITB at a later stage and facilitate the development of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis) drug resistance. Ultimately, ATT may critically delay proper CD treatment and patients may be at risk of exacerbation or complications.

During the past decade, new diagnostic methods, such as M. tuberculosis PCR, immunohistochemistry and interferon-γ release assays have been evaluated for the differentiation of the two diseases. Unfortunately, studies on their sensitivity and specificity have been conflicting and their diagnostic utility is uncertain. New diagnostic algorithms or recommendations have emerged with nearly every paper published[9-13].

Traditional diagnostic modalities, such as acid-fast staining of biopsies or sputum, M. tuberculosis culturing, Mantoux tuberculin skin testing, and chest X-rays, are often negative in extra-pulmonary TB[1,5,14]. Currently, empiric prescription of standard ATT for eight weeks followed by re-evaluation of the diagnosis remains the commonly applied diagnostic modality[2,12,14,15].

In this prospective multi-centre study, we evaluated routine clinical, endoscopic and laboratory variables currently applied for diagnosing ITB in Southern India. Using these variables we evaluated the ability to differentiate ITB from CD.

Thirty-eight patients with ITB and 37 patients with CD were prospectively included from four South Indian medical centres in a consecutive manner from October 2009 to July 2012. Centre investigators identified patients with ITB or CD. The inclusion/exclusion criteria were thoroughly discussed at meetings and clarified in the study protocol (Table 1). Although generally recommended in the literature, M. tuberculosis specific microbiologic diagnostics were not routinely applied as our study was descriptive and sought to reflect clinical practice in the region. All ITB patients were prescribed ATT for six months according to the Indian Revised National Tuberculosis Control Program[16].

| Criteria | |

| Inclusion criteria | |

| Intestinal tuberculosis (as per modified Paustian’s criteria[31,32]: (a), and one or more of (b) and (c) had to be fulfilled) | (a) Endoscopic apparent intestinal tuberculosis: transverse ulcers, pseudopolyps, involvement of fewer than four intestinal segments, patulous ileo-coecal valve (b) Histological evidence of tubercles/granulomas with caseation necrosis in intestinal biopsies (c) Clinical response to antituberculous chemotherapeutic drug treatment (ATT) trial |

| Crohn’s disease (as per ECCO guidelines 2010[33] and management consensus of inflammatory bowel disease for the Asia-Pacific region 2006[34]) | Exclusion of infectious enterocolitis Endoscopic: ileal disease, rectal sparing, confluent deep linear ulcers, aphthoid ulcers, deep fissures, fistulae, skip lesions (segmental disease), cobble-stoning Histological: focal (discontinuous) chronic (lymphocytes and plasma cells) inflammation and patchy chronic inflammation, focal crypt irregularity (discontinuous crypt distortion) and granulomas (not related to crypt injury) Samples from ileum: irregular villous architecture |

| Exclusion criteria | |

| Malignancy | |

| HIV positive | |

| Age below 18 yr | |

A detailed medical history was acquired prior to physical examination and further investigations, all of which were recorded in standardised electronic questionnaires.

C-reactive protein (CRP) was analysed in blood serum. Retrograde video ileocolonoscopy with biopsies was performed in each centre after proper colon preparation. Any observed pathology was recorded on video and described according to standardised criteria: anatomic location of lesion(s), aphthous and/or deep ulcers nodularity of mucosa, fissures, and strictures. All four centre investigators were senior consultant gastroenterologists and classified pathology according to their clinical experience. Tissue biopsies obtained during ileocolonoscopy were fixated in 10% formalin and preserved in blocks. Sections of 4 μm thickness were cut from blocks and stained by Haematoxylin-Eosin and then evaluated by pathologists.

Patients were scheduled to follow-up clinical evaluation after 8 wk of ATT or immune suppressive therapy. Treatment response was evaluated on clinical grounds, with improvement in signs and symptoms being regarded as confirmatory for diagnosis.

The study was approved by The Ethical Committee of Sree Gokulam Medical College and Research Foundation, Trivandrum, India. Written informed consent was obtained after explaining the study to the participants in their preferred language.

Due to the skewed distribution of data and limited sample size, the continuous variables were described with median and range, while the categorical variables were listed as counts and percentages. Crude differences between disease type and selected disease associated variables were assessed with a Mann-Whitney Wilcoxon test for the continuous variables. χ2 tests were applied to compare pairs of categorical variables.

First, all variables possibly associated with disease type (ITB or CD) were subject to univariate logistic regression. Then, variables with sufficient number of recordings and P < 0.05 were entered into a multiple logistic regression model (MLR). The results were expressed as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and adjusted for known confounders. ITB was used as a reference for the ease of interpretation. All tests were two-sided. We considered our study to be an exploratory analysis, therefore P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant and we did not perform any correction for multiple testing.

All data were analysed in cooperation with a biomedical statistician using SPSS statistical software Version 18.1.

Baseline data were completed for all participants. In total, 24 of 75 patients were lost to follow-up clinical evaluation: 19 ITB and 5 CD patients. Follow-up endoscopy was only achieved in the minority of the patients, as many either refused repeat endoscopy or were lost to follow-up after clinical evaluation at 2 mo. Two patients initially treated with ATT had their diagnosis revised to CD after endoscopy at 6 mo. None of the CD patients had their diagnosis revised to ITB.

Any possible associations between disease type (ITB or CD) and symptoms, signs and other disease associated factors are presented in Table 2. We found an association (P < 0.05) between having ITB and experiencing weight loss and watery diarrhoea. A diagnosis of CD was associated with pain in the right lower abdominal quadrant at examination, malaise and nausea. Weight measurements at examination revealed lower body weight in the ITB patients (median: 52 kg, IQR 13) than in the CD patients (median: 59 kg, IQR 12), P = 0.001.

| Symptoms, signs and factors | ITB (n = 38) | CD (n = 37) | P value |

| Duration of illness prior to care (mo), median | 6 | 6 | 0.581 |

| Min-Max | 0-60 | 1-78 | |

| Body mass index, median | 19.6 | 22.7 | 0.011 |

| Min-Max | 11.2-26.0 | 15.6-31.2 | |

| Waist circumference (cm), median (inter quartile range) | 77 (11) | 80 (15) | 0.821 |

| Change in bowel habit | 28/37 (76) | 34 (92) | 0.112 |

| Weight loss in history of current complaint | 27/37 (73) | 14 (38) | < 0.012 |

| Malaise in history of current complaint | 23/37 (62) | 32 (87) | 0.032 |

| Abdominal pain in history of current complaint | 35 (92) | 33 (89) | 0.712 |

| Nausea in history of current complaint | 20/37 (54) | 31 (84) | 0.012 |

| Recent fever | 17/37 (47) | 9/36 (25) | 0.062 |

| Cachexia at examination | 22/36 (61) | 21 (57) | 0.712 |

| Current watery diarrhoea | 21/33 (64) | 12/36 (33) | 0.012 |

| Daily bowel evacuations, median, max (inter quartile range) | 3 (3) | 3 (0) | 0.241 |

| Pain in right lower abd. quadrant on exam | 15/28 (54) | 27/30 (90) | < 0.012 |

ITB patients had a lower body mass index than the CD patients, but cachexia observed by the centre investigators on physical examination was equally distributed between the two groups. The duration of illness prior to receiving care did not differ between the groups. Abdominal pain and altered bowel habits within the last year were commonly reported by both patient groups. The patients had the same average number of bowel evacuations per day. Chest symptoms were noted in four ITB patients and none of the CD patients.

The median CRP was higher in ITB patients (10.7 mg/L, normal reference < 6.0 mg/L) than in CD patients (4.3 mg/L). However, the difference did not reach statistical significance (Table 3).

| Clinical variables | ITB(n = 38) | CD(n = 37) | P value |

| CRP (mg/L), median | 10.7 | 4.3 | 0.131 |

| Min-max | 0.2-70.5 | 0.3-49.8 | |

| Features on ileocolonoscopy, n endoscopy reports | 31/38 | 37 | |

| Localised intestinal inflammation, n | 12 | 4 | 0.012 |

| 3 or more inflamed intestinal segments, n | 9 | 27 | < 0.012 |

| Aphtous ulcers, n | 12 | 16 | 0.712 |

| Deep ulcers, n | 19 | 24 | 0.902 |

| Mucosal nodularity, n | 17 | 2 | < 0.012 |

| Histopathological evidence of granulomas(s), n | 10/30 | 2/35 | < 0.012 |

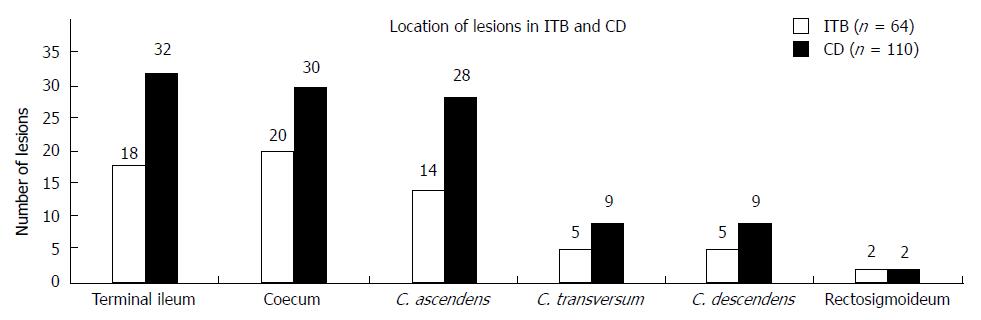

Ileocolonoscopy showed that CD patients had a more widespread disease with involvement of multiple intestinal segments compared to the ITB patients’ more localised disease, P < 0.01. Conversely, mucosal nodularity was more frequent in the ITB patients, P < 0.01. None of the other disease associated macroscopic features differed between the groups (Table 3). Lesions observed on endoscopy were predominantly located in the ileocoecal area and the ascending colon in both patient groups. However, the number of lesions observed was higher in the CD group of patients (110 lesions vs 64 lesions) (Figure 1).

Granulomas were more commonly detected in the biopsies from the ITB patients than the CD patients, P < 0.01 (Table 3).

There were no differences between the groups with regard to patient age and sex distribution. In the ITB group, 42% of the patients reported living in urban areas, and 53% held a high school degree or higher. Conversely, 65 % of the CD patients were urban dwellers and 73% held a high school degree or higher. The median household income in the CD group was nearly twice the median household income of those with ITB [9000 rupees (128 €) vs 5000 rupees (71 €)] (Table 4).

Logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate possible associations between selected disease variables and the outcome (ITB or CD). Variables such as malaise, nausea and watery diarrhoea were excluded from the models due to their confounding potential.

Our first model contained clinical and epidemiological data and included four independent variables: weight loss within last year prior to care, pain in the right lower abdominal quadrant at examination, age and sex. The distributions of the latter two were equal between the groups and were excluded from the model.

Weight loss and abdominal pain remained independent predictors of ITB or CD. Patients with weight loss but no abdominal pain were nearly 9 times more likely to have ITB than patients with the opposite features, OR = 8.6, 95%CI: 2.1-35.6. Conversely, patients with pain in the right abdominal quadrant on examination but no weight loss were 10 times more likely to have CD, adjusted OR 10.1, 95%CI: 2.0-51.3 (Table 5).

| P value | OR | 95%CI | Associated with | |

| Multiple logistic regression model 1 | ||||

| Weight loss | 0.003 | 8.6 | 2.1-35.6 | ITB |

| Pain in right lower abdominal quadrant on examination | 0.005 | 10.1 | 2.0-51.3 | CD |

| Multiple logistic regression model 2 | ||||

| Mucosal nodularity | 0.001 | 18.9 | 3.5-102.8 | ITB |

| Multi-segment involvement (3 or more) | 0.005 | 5.9 | 1.7-20.6 | CD |

Our second model contained endoscopic and epidemiological data and included four independent variables: 3 or more involved intestinal segments, nodularity of mucosa, age and sex. The age and sex distributions were equal between the groups and these variables were excluded from the model. Involvement of 3 or more intestinal segments and nodularity of mucosa remained associated with the type of diagnosis (ITB or CD). The strongest independent predictor was mucosal nodularity. ITB patients were 19 times more likely to present with this feature on endoscopy when controlling for the other factors in the model, OR = 18.9, 95%CI: 3.5-102.8. Conversely, a patient with involvement of 3 or more intestinal segments on endoscopy was 6 times more likely to suffer from CD, adjusted OR = 5.9, 95%CI: 1.7-20.6 (Table 5).

Weight loss is typically found in TB disease in general and is traditionally referred to as “wasting”. The reasons for loss of weight in TB may be multi-factorial. As cachectic patients lose body fat, their leptin production subsequently drops, resulting in loss of appetite and further weight reduction. Energy expenditure has not been found to be increased in TB patients. Thus, wasting has been explained by decreased energy uptake rather than increased energy consumption[17,18]. Weight loss as a presenting symptom of TB has previously been found in 45% of patients with pulmonary TB[19]. Interestingly, 73% of our ITB patients experienced weight loss prior to care. Intestinal involvement may result in malabsorption of nutrients and decreased intestinal transit time[20,21]. Therefore, weight loss in ITB patients may not only reflect the general wasting observed in TB, but also the intestinal involvement itself.

Weight loss may occur in patients with CD as well and has been investigated in several previous studies. In patients without small intestinal involvement and malabsorption other mechanisms may lead to weight reduction. As in TB, a relative decrement in energy intake rather than energy loss has been found to be a major contributor to loss of body mass in colonic CD[22]. Intestinal inflammation may result in inadequate protein sparing mechanisms. Weight loss may therefore be more pronounced in patients with low protein intake and intestinal disease. CD patients with active disease also require excessive energy consumption compared to healthy people.

With respect to the drop in leptin production and decreased energy intake, weight loss in ITB seems stronger than in CD. Weight loss was reported more frequently in ITB patients, and their body weight at examination was lower than in the CD patients. Data of our patients’ weight prior to receiving care was unavailable. Thus, whether the ITB patients’ baseline body weight prior to illness was lower than in the CD patients is unknown.

Pain in the right lower abdominal quadrant was more frequently reported on physical examination in our CD patients than in the ITB patients (P < 0.01). We made a distinction between abdominal pain as a symptom in the patient’s history and localised abdominal pain as a sign on physical examination. Our findings of abdominal pain on examination, predominantly in CD patients and only to a lesser degree in ITB patients, may reflect a higher level of inflammation and a lower threshold for pain in CD compared with ITB. This is further supported by the finding of relatively more lesions in the ileocecal and ascending colon areas in our CD patients. Abdominal pain as a symptom of ITB is well known from the literature, but distinguishing it from pain on physical examination has not been described previously.

Previous reports have described skip lesions and extensive disease to be a more frequent finding of CD[2,23]. Our study confirms this with more CD patients suffering from involvement of three or more intestinal segments compared to those with ITB (P < 0.01). Thus, ITB is localised to the predilection site of M. tuberculosis infection, usually the terminal ileum or coecum. Distal segments are more frequently involved in CD. Although the phenotype of CD in India seems similar to CD elsewhere, environmental triggers of disease may vary between different geographical regions and possibly affect the distribution of lesions[1,4,8].

Nodularity of the intestinal mucosa is a well known feature of ITB[2,3,24]. We identified nodularity in 17 ITB patients and two CD patients. Although nodular mucosa may be a typical finding in ITB, a range of other aetiologies should be kept in mind[25].

With regards to patient demographics, a greater proportion of our CD patients were living in urban communities. We found a trend of CD patients having a higher household income and level of education. This is somewhat similar to the so-called “blue collar findings” reported in studies on IBD, where CD as opposed to ulcerative colitis seems more prevalent in persons with higher socioeconomic status[4,26]. The median age of 33 years at diagnosis in both ITB and CD patients is equivalent to observations in previous reports[2,8,27].

Males were over-represented in our cohort with a male to female ratio of 3 to 2. Other reports on CD in Asia have described a similar 3:2 male predominance[8,27]. In India, this may reflect inequity in access to health care[28].

Our ITB patients were mainly living in rural areas, with a rural to urban ratio of 3 to 2. Epidemiological studies on TB in India have shown different case detection between rural and urban dwellings[29,30]. It is known that TB transmits more easily in communities with lower socioeconomic status because people live more densely with poorer ventilation and hygienic facilities. The relatively lower household income and educational level in our ITB patients may simply reflect that our ITB patients were predominantly rural dwellers with limited access to higher education and income.

By chance, we recruited equal numbers of ITB and CD patients during the 33-mo inclusion period. This result may be a random finding, but it could also suggest that the incidence of CD in South India is higher than previously assumed. According to epidemiological studies throughout Asia the incidence of IBD including CD could be increasing[4].

The study has some limitations. Of the four variables found to be predictive of disease, “pain” and “nodularity” could not be further sub-classified. Conversely, “weight loss” and “number of involved intestinal segments” allowed for objective estimation: a significant difference in body weight was found between the groups and the endoscopists scored the number of involved segments according to pre-defined anatomic locations.

Our cohort of 75 patients only allows for crude statistical analyses. This is reflected by the wide confidence intervals of the ORs established by logistic regression analysis. Therefore, although statistically significant differences were found between the groups with regard to selected variables, the precision of the estimates is limited. Furthermore, to draw any conclusions on differences between the study groups or the background population with regard to demographics or epidemiology is not feasible. Despite repeated attempts to contact patients for scheduling appointments, one third of the patients were lost to follow-up. Hence, we are unaware of their clinical course and could not confirm their diagnosis.

As we sought to describe the current clinical practice in Southern India, only diagnostic modalities routinely available were evaluated. Although positive acid-fast staining and/or culturing of M. tuberculosis from intestinal biopsies have high positive predictive values for TB diagnosis, these methods were not applied, possibly due to their low yield shown in previous studies[1,5,14]. Additionally, it may be unfavourable to leave a patient untreated pending the result of a slow growing M. tuberculosis culture. As negative chest radiographs may not rule out ITB, routine chest X-ray was not performed in our cohort. Chest symptoms were recorded in four of our 38 ITB patients. CT or MR enterography was not applied in the participating centres during the study period.

Our multi-centre design including four study sites strengthens the study as selection bias was avoided. The standardisation of histopathological evaluation of biopsies between the different pathologists was limited and microscopic features could only partially be pooled for analysis. Similarly, although inter-observer variability was reduced by use of standardised endoscopy report forms, interpretations of pathology may have varied between the endoscopists, Apart from endoscopy and histopathology, all laboratory analyses were conducted by one person and all case record forms were standardised to multiple choice answers.

Of all clinical features, weight loss favoured a diagnosis of ITB while right lower abdominal pain on physical examination favoured a diagnosis of CD.

Endoscopically, nodularity of the mucosa was found to be a hallmark of ITB. Involvement of three or more intestinal segments favoured a diagnosis of CD, whereas the majority of our ITB patients had localised disease. The features of our patients are consistent with previous descriptions of ITB and CD from the Indian subcontinent. Interestingly, nearly as many CD patients as ITB patients were recruited from the secondary and tertiary centres of this study. This result suggests that CD is increasing in South India.

Currently, differentiating between ITB and CD is time consuming, labour intensive and costly. Clinical features distinguishing between the diseases may overlap, and a range of other diseases may present identically to ITB and CD. Simple, inexpensive and rapid diagnostic modalities applicable in populations of both high and low TB endemicity are needed for the differentiation and diagnosis of ITB and CD.

G Larsson would like to thank the staff at the Population Health and Research Institute in Trivandrum, India, with special regards to Mrs. Suja, for handling and preparing patient samples and filing the data. Special thanks also to the investigators at Madurai (Dr. Thayumanavan B) and Coimbatore (Dr. Mohan Prasad VG) centres for recruiting patients and to Dr. Holm B and Mrs. Tangen AM at Lovisenberg Diaconal Hospital for allowing the initiation and financial support of this study. Dr. Klepp PC is acknowledged for proofreading and thorough support during the study. The source population consisted of patients enrolled from four different medical institutions in South India: Department of Gastroenterology, Sree Gokulam Medical College, Trivandrum, Kerala; Department of Gastroenterology, Coimbatore Medical College, Coimbatore, Kerala; Department of Gastroenterology, Madurai Medical College, Madurai, Tamil Nadu; Department of Gastroenterology, Tuticorin, Tamil Nadu.

Crohn’s disease (CD) is on the increase worldwide while tuberculosis (TB) is re-emerging in areas of low TB endemicity. Intestinal TB (ITB) may easily be confounded with CD, a mimicry that could pose diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Authors prospectively evaluated routine clinical, endoscopic and laboratory variables currently available in Southern India. By employing these variables, they evaluated the ability to differentiate ITB from CD.

Differentiating between ITB and CD may be time consuming, labour intensive and costly. Modern tools using PCR, immunohistochemistry and interferon-γ release assays have been studied. However, their diagnostic yield remains uncertain and new diagnostic algorithms or recommendations emerge with nearly every paper published. Traditional diagnostic methods such as acid-fast staining of biopsies or sputum, Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis) culturing, Mantoux tuberculin skin testing, and chest X-rays, are often negative in extra-pulmonary TB. Today, empiric prescription of antituberculous chemotherapy for eight weeks followed by re-evaluation of the diagnosis is commonly applied as a diagnostic modality. Simple, inexpensive and rapid diagnostic methods applicable in populations of both high and low TB endemicity are needed for the differentiation and diagnosis of ITB and CD.

Of all clinical features, weight loss favoured a diagnosis of ITB while right lower abdominal pain on physical examination favoured a diagnosis of CD. Endoscopically, mucosal nodularity was found to be a hallmark of ITB, while involvement of three or more intestinal segments favoured a diagnosis of CD. The features of their patients are consistent with previous descriptions of ITB and CD from the Indian subcontinent. However, they also demonstrated that clinical features overlap. The same number of CD patients as ITB patients were recruited from the secondary and tertiary centres of this study and authors stress clinicians should be highly cautious when trying to distinguish between the diseases.

By understanding the differences and the similarities between these two diseases co-existing on the Indian sub-continent, authors may apply new diagnostic modalities to the diagnostic work-up and further evaluate their performance in the field. Their study adds valuable clinical information that may help target the development of simple and inexpensive diagnostics in the future.

Polymerase chain reaction, or PCR, is a laboratory technique used to make multiple copies of a segment of DNA, i.e., mycobacterial DNA; Immunohistochemistry is a molecular biological method which detects antigens in tissue sections by means of immunological and chemical reactions; Interferon-γ release assays detect latent tuberculosis infection by measuring in vitro interferon-γ release in response to antigens present in M. tuberculosis; Leptin is an adipocyte derived hormone which regulates energy intake and expenditure, metabolism and behaviour.

This is a prospective, multi-center exploratory study analysing whether routinely used clinical variables could help to differentiate patients with ITB from CD. In a small series of patients the authors find a marginally significant difference in four variables - they found weight loss and nodularity of the mucosa to be independently associated with ITB. Right lower abdominal quadrant pain on examination and involvement of ≥ 3 intestinal segments were independently associated with CD.

P- Reviewers: Abraham P, Edward C, Koch TR S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Amarapurkar DN, Patel ND, Rane PS. Diagnosis of Crohn’s disease in India where tuberculosis is widely prevalent. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:741-746. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Makharia GK, Srivastava S, Das P, Goswami P, Singh U, Tripathi M, Deo V, Aggarwal A, Tiwari RP, Sreenivas V. Clinical, endoscopic, and histological differentiations between Crohn’s disease and intestinal tuberculosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:642-651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Mukewar S, Mukewar S, Ravi R, Prasad A, S Dua K. Colon tuberculosis: endoscopic features and prospective endoscopic follow-up after anti-tuberculosis treatment. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2012;3:e24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ng SC, Bernstein CN, Vatn MH, Lakatos PL, Loftus EV, Tysk C, O’Morain C, Moum B, Colombel JF. Geographical variability and environmental risk factors in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2013;62:630-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 470] [Cited by in RCA: 442] [Article Influence: 36.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Almadi MA, Ghosh S, Aljebreen AM. Differentiating intestinal tuberculosis from Crohn’s disease: a diagnostic challenge. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1003-1012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Li X, Liu X, Zou Y, Ouyang C, Wu X, Zhou M, Chen L, Ye L, Lu F. Predictors of clinical and endoscopic findings in differentiating Crohn’s disease from intestinal tuberculosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:188-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sri SS, Banginwar AS. Textbook of pulmonary and extra-pulmonary tuberculosis. 6th ed. New Dehli: Metha Publishers 2009; . |

| 8. | Das K, Ghoshal UC, Dhali GK, Benjamin J, Ahuja V, Makharia GK. Crohn’s disease in India: a multicenter study from a country where tuberculosis is endemic. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1099-1107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pulimood AB, Peter S, Rook GW, Donoghue HD. In situ PCR for Mycobacterium tuberculosis in endoscopic mucosal biopsy specimens of intestinal tuberculosis and Crohn disease. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:846-851. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Jin XJ, Kim JM, Kim HK, Kim L, Choi SJ, Park IS, Han JY, Chu YC, Song JY, Kwon KS. Histopathology and TB-PCR kit analysis in differentiating the diagnosis of intestinal tuberculosis and Crohn’s disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:2496-2503. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Ince AT, Güneş P, Senateş E, Sezikli M, Tiftikçi A, Ovünç O. Can an immunohistochemistry method differentiate intestinal tuberculosis from Crohn’s disease in biopsy specimens? Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:1165-1170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pulimood AB, Amarapurkar DN, Ghoshal U, Phillip M, Pai CG, Reddy DN, Nagi B, Ramakrishna BS. Differentiation of Crohn’s disease from intestinal tuberculosis in India in 2010. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:433-443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 13. | Lei Y, Yi FM, Zhao J, Luckheeram RV, Huang S, Chen M, Huang MF, Li J, Zhou R, Yang GF. Utility of in vitro interferon-γ release assay in differential diagnosis between intestinal tuberculosis and Crohn’s disease. J Dig Dis. 2013;14:68-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Epstein D, Watermeyer G, Kirsch R. Review article: the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease in populations with high-risk rates for tuberculosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:1373-1388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ouyang Q, Tandon R, Goh KL, Ooi CJ, Ogata H, Fiocchi C. The emergence of inflammatory bowel disease in the Asian Pacific region. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2005;21:408-413. [PubMed] |

| 16. | API Consensus Expert Committee. API TB Consensus Guidelines 2006: Management of pulmonary tuberculosis, extra-pulmonary tuberculosis and tuberculosis in special situations. J Assoc Physicians India. 2006;54:219-234. [PubMed] |

| 17. | van Crevel R, Karyadi E, Netea MG, Verhoef H, Nelwan RH, West CE, van der Meer JW. Decreased plasma leptin concentrations in tuberculosis patients are associated with wasting and inflammation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:758-763. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Macallan DC, McNurlan MA, Kurpad AV, de Souza G, Shetty PS, Calder AG, Griffin GE. Whole body protein metabolism in human pulmonary tuberculosis and undernutrition: evidence for anabolic block in tuberculosis. Clin Sci (Lond). 1998;94:321-331. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Miller LG, Asch SM, Yu EI, Knowles L, Gelberg L, Davidson P. A population-based survey of tuberculosis symptoms: how atypical are atypical presentations? Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:293-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tandon RK, Bansal R, Kapur BM. A study of malabsorption in intestinal tuberculosis: stagnant loop syndrome. Am J Clin Nutr. 1980;33:244-250. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Yadav P, Das P, Mirdha BR, Gupta SD, Bhatnagar S, Pandey RM, Makharia GK. Current spectrum of malabsorption syndrome in adults in India. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2011;30:22-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Rigaud D, Angel LA, Cerf M, Carduner MJ, Melchior JC, Sautier C, René E, Apfelbaum M, Mignon M. Mechanisms of decreased food intake during weight loss in adult Crohn’s disease patients without obvious malabsorption. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;60:775-781. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Lee YJ, Yang SK, Byeon JS, Myung SJ, Chang HS, Hong SS, Kim KJ, Lee GH, Jung HY, Hong WS. Analysis of colonoscopic findings in the differential diagnosis between intestinal tuberculosis and Crohn’s disease. Endoscopy. 2006;38:592-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Alvares JF, Devarbhavi H, Makhija P, Rao S, Kottoor R. Clinical, colonoscopic, and histological profile of colonic tuberculosis in a tertiary hospital. Endoscopy. 2005;37:351-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Dilauro S, Crum-Cianflone NF. Ileitis: when it is not Crohn’s disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2010;12:249-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ. Crohn’s disease. Lancet. 2012;380:1590-1605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1347] [Cited by in RCA: 1529] [Article Influence: 117.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Prideaux L, Kamm MA, De Cruz PP, Chan FK, Ng SC. Inflammatory bowel disease in Asia: a systematic review. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:1266-1280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Balarajan Y, Selvaraj S, Subramanian SV. Health care and equity in India. Lancet. 2011;377:505-515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 667] [Cited by in RCA: 487] [Article Influence: 34.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Chadha VK. Tuberculosis epidemiology in India: a review. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005;9:1072-1082. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Mukherjee A, Saha I, Sarkar A, Chowdhury R. Gender differences in notification rates, clinical forms and treatment outcome of tuberculosis patients under the RNTCP. Lung India. 2012;29:120-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | PAUSTIAN FF, BOCKUS HL. So-called primary ulcerohypertrophic ileocecal tuberculosis. Am J Med. 1959;27:509-518. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Logan VS. Anorectal tuberculosis. Proc R Soc Med. 1969;62:1227-1230. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Van Assche G, Dignass A, Panes J, Beaugerie L, Karagiannis J, Allez M, Ochsenkühn T, Orchard T, Rogler G, Louis E. The second European evidence-based Consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease: Definitions and diagnosis. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:7-27. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Ouyang Q, Tandon R, Goh KL, Pan GZ, Fock KM, Fiocchi C, Lam SK, Xiao SD. Management consensus of inflammatory bowel disease for the Asia-Pacific region. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:1772-1782. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |