Published online Dec 7, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i45.8181

Revised: October 22, 2013

Accepted: November 3, 2013

Published online: December 7, 2013

Processing time: 83 Days and 12.4 Hours

Recent progress in the research regarding the molecular pathogenesis and management of gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma is reviewed. In approximately 90% of cases, Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection plays the causative role in the pathogenesis, and H. pylori eradication is nowadays the first-line treatment for this disease, which leads to complete disease remission in 50%-90% of cases. In H. pylori-dependent cases, microbe-generated immune responses, including interaction between B and T cells involving CD40 and CD40L co-stimulatory molecules, are considered to induce the development of MALT lymphoma. In H. pylori-independent cases, activation of the nuclear factor-κB pathway by oncogenic products of specific chromosomal translocations such as t(11;18)/API2-MALT1, or inactivation of tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced protein 3 (A20) are considered to contribute to the lymphomagenesis. Recently, a large-scale Japanese multicenter study confirmed that the long-term clinical outcome of gastric MALT lymphoma after H. pylori eradication is excellent. Treatment modalities for patients not responding to H. pylori eradication include a “watch and wait” strategy, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, rituximab immunotherapy, and a combination of these. Because of the indolent behavior of MALT lymphoma, second-line treatment should be tailored in consideration of the clinical stage and extent of the disease in each patient.

Core tip: Recent progress in the research regarding the molecular pathogenesis and management of gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma is reviewed. Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication leads to complete disease remission in 50%-90% of cases. In H. pylori-independent cases, activation of nuclear factor κB pathway by chromosomal translocations such as t(11;18)/API2-MALT1, or inactivation of A20 are considered to contribute to the lymphomagenesis. A recent Japanese multicenter study confirmed the excellent long-term outcome of gastric MALT lymphoma after H. pylori eradication. Strategies for patients not responding to H. pylori eradication should be tailored in consideration of clinical stage and the disease extent in each patient.

-

Citation: Nakamura S, Matsumoto T.

Helicobacter pylori and gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma: Recent progress in pathogenesis and management. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(45): 8181-8187 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v19/i45/8181.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v19.i45.8181

Extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma is an indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma derived from marginal zone B-cells, which occurs in a number of extranodal organs, including the gastrointestinal tract, lung, salivary gland, thyroid, ocular adnexa, liver or skin[1]. Among these, the stomach is the most frequent site for MALT lymphoma. Gastric MALT lymphoma comprises 40%-50% of primary gastric lymphomas, 20%-40% of all extranodal lymphomas, 4%-9% of all non-Hodgkin lymphomas, and 1%-6% of all gastric malignancies[2-5]. Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) plays a causative role in the development of gastric MALT lymphoma, and the eradication of H. pylori leads to a complete disease remission (CR) in 50%-90% of cases[6,7].

In the present paper, we review the current knowledge on the etiology, diagnosis and optimal management strategies for patients with gastric MALT lymphoma, with special reference to its association with H. pylori infection and efficacy of the eradication therapy.

A link of H. pylori with gastric MALT lymphoma was first suggested in 1991 by identification of the bacteria in the vast majority of patients[8]. This association was supported by subsequent epidemiological and histopathological studies[9,10]. Approximately 90% of patients with gastric MALT lymphoma are infected with H. pylori[7,11,12], and about 70% of the cases respond to H. pylori eradication[6,7]. In such responders, survival of the lymphoma cells depends critically upon the microbe-generated immune responses[13]. Laboratory studies demonstrated that the growth of neoplastic B cells is stimulated by tumor-infiltrating H. pylori-specific T-cells, which require interaction between B and T cells involving CD40 and CD40L co-stimulatory molecules[14-19]. Thus, the genesis of H. pylori-dependent gastric MALT lymphoma is now considered as follows: an H. pylori infection results in T cell-dependent responses through the classic germinal center reaction, and thus generates reactive B and T cells. The H. pylori-specific T cells raised in the reactive component then migrate to the marginal zone/tumor area and provide non-cognate help to autoreactive neoplastic B cells, which may involve stimulation of CD40 and other surface receptors by soluble ligands and cytokines[13,19].

Recently, Munari et al[20] reported that high levels of a proliferation-inducing ligand (APRIL) were produced exclusively by tumor-infiltrating macrophages in H. pylori-dependent gastric MALT lymphoma cases, and that macrophages produced APRIL on direct stimulation with both H. pylori and H. pylori-specific T cells. APRIL is a tumor necrosis factor (TNF) superfamily member known to be important for B-cell development, maturation and survival. It should be noted that APRIL-producing macrophages were dramatically reduced on lymphoma regression induced by H. pylori eradication[20]. These findings suggest that APRIL may also play some important role in the H. pylori-dependent lymphomagenesis.

Genetic abnormalities are common in gastric MALT lymphomas. To date, a number of chromosomal translocations have been described in MALT lymphomas. Among these, t(11;18) (q21;q21)/API2-MALT1, t(1;14) (p22;q32)/BCL10-IGH, t(14;18) (q32;q21)/IGH-MALT1 and t(3;14) (p13;q32)/FOXP1-IGH are replicable[1,13,21]. MALT1 and BCL10 proteins are involved in surface immune receptor-mediated activation of the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) transcription factor; the chromosomal translocations involving these genes are believed to exert their oncogenic activities through constitutive activation of the NF-κB pathway, leading to expression of a number of genes important for cell survival and proliferation[21].

In gastric MALT lymphoma, t(11;18)/API2-MALT1 is the most frequent translocation, which is detected in 15%-24% of cases. The translocation fuses the N-terminal region of API2 to the C-terminal region of MALT1 and generates a functional chimeric fusion, which gains the ability to activate the NF-κB pathway[13,21]. Clinically, t(11;18) is more frequently associated with absence of H. pylori infection, and the majority of the translocation-positive cases do not respond to H. pylori eradication therapy[7,11,21,22]. Interestingly, t(11;18)-positive cases rarely transform to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL)[23].

Recently, the TNF-alpha-induced protein 3 gene (TNFAIP3, A20), a negative regulator of NF-κB, was identified as the target of 6q23 deletion in many cases of MALT lymphoma[13,24,25]. A20 mutation and deletion, which lead to A20 inactivation, are preferentially found in MALT lymphoma of the ocular adnexa, salivary glands, thyroid and liver. It is considered that A20-mediated oncogenic activities in MALT lymphoma depend on the NF-κB activation triggered by TNF or other unidentified molecules[13]. In gastric MALT lymphomas, however, A20 deletion was detected only in 2 of 29 (7%) cases examined[25]. Thus, further investigations are needed to determine to what extent A20 inactivation contributes to the genesis of gastric MALT lymphoma.

The diagnosis of gastric MALT lymphoma should be based on the histopathological criteria according to the World Health Organization classification, using tissue specimens appropriately obtained by biopsy or surgery[1,5,26]. Histologically, the small to medium-sized neoplastic lymphoid cells (centrocyte-like cells) infiltrate around reactive follicles showing marginal zone growth pattern, which often infiltrate into gastric glands causing destruction of the epithelial cells (lymphoepithelial lesions)[1,26]. Immunohistochemically, the neoplastic cells of MALT lymphoma are usually CD20+, CD79a+, CD5-, CD10-, CD23-, CD43+/-, cyclin D1-. Staining for Ki-67 may help in identifying components of DLBCL. Cytogenetic analyses using G-banding, reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction and/or fluorescence in situ hybridization for t(11;18)/API2-MALT1 or other chromosomal translocations are also useful for confirming the diagnosis[1,21,26].

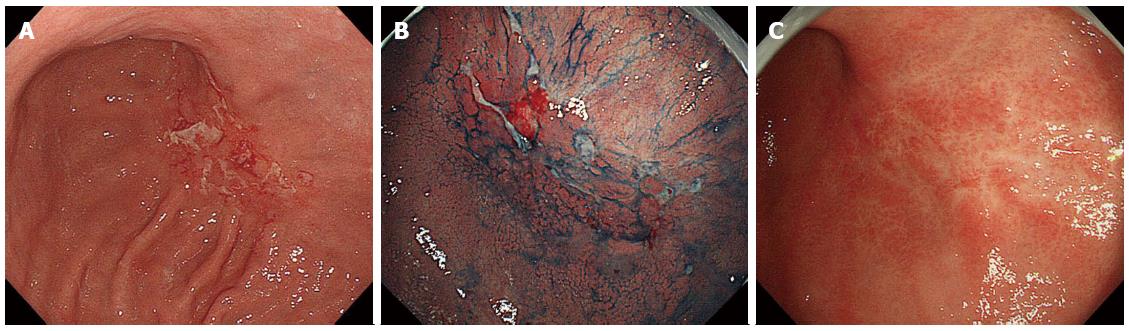

The standard macroscopic classifications for gastric lymphomas have not been established. In Western countries, gastric B-cell lymphomas have been endoscopically classified either as ulcerative (34%-69%), mass/polypoid (26%-35%), diffusely infiltrating (15%-40%), or other types[27-29]. We previously reported that 197 Japanese cases of primary gastric B-cell lymphoma (MALT lymphomas and DLBCLs) were macroscopically classified as superficial-spreading (46%), mass-forming (41%), diffuse-infiltrating (6%), or other types (8%)[30]. Importantly, the most frequent macroscopic type in gastric MALT lymphomas is superficial type (Figure 1), while that in gastric DLBCLs is mass/polypoid type[29,30].

An appropriate clinical staging is mandatory in order to determine the optimal management for malignant lymphomas. For the staging classification in patients with gastric MALT lymphoma, the Ann Arbor staging system with its modifications by Musschoff and Radaszkiewicz (I1E, I2E, II1E, II2E, IIIE, or IV) was recommended in the consensus report of the EGILS (European Gastro-Intestinal Lymphoma Study) group[26]. To date, however, the Lugano International Conference (Blackledge) classification (I, II1, II2, IIE, or IV) has been widely applied for the clinical staging in gastrointestinal lymphomas (Table 1)[31]. In addition to esophagogastroduodenoscopy, the following are recommended for the initial staging workup: physical examination (including peripheral lymph nodes and Waldeyer’s ring), complete hematological biochemical examinations (including LDH and β2-microglobulin), computerized tomography of abdomen and pelvis, and endoscopic ultrasonography[26]. In our opinion, however, ileocolonoscopy, bone marrow aspiration or biopsy, and fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography should also be included. In addition, endoscopic examinations of the small bowel (balloon-assisted endoscopy or capsule endoscopy) can be considered[32].

| Stage | Definition | Description |

| Stage I | Tumor confined to gastrointestinal tract | Single primary site or multiple, non contiguous lesions |

| Stage II | Tumor extending into abdomen from primary gastrointestinal site | |

| Nodal involvement | ||

| II1 local | Paragastric (gastric cases) or paraintestinal (intestinal cases) nodal involvement | |

| II2 distant | Mesenteric, paraaoritic, paracaval, pelvic or inguinal nodal involvement | |

| Stage IIE | Penetration of serosa to involve adjacent organs or tissues | Gastrointestinal lesion extending to involve adjacent organs, i.e., penetration, direct invasion, perforation or peritonitis by lymphoma |

| Stage IV | Disseminated extranodal involvement, or supra-diaphragmatic nodal involvement | Cases with Ann-Arbor stage III disease should be included |

The first-line treatment of all gastric MALT lymphomas is H. pylori eradication therapy[1,26,33]. In patients with stage I/II1 disease, CR is achieved in 50%-90% of cases only by H. pylori eradication[6,7]. Histological evaluation of post-treatment biopsies should be performed according to the Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes de l’Adulte (GELA) grading system (Table 2)[26,34]. Various predictive factors for resistance to H. pylori eradication therapy have been described, including absence of H. pylori infection, advanced stage, proximal location in the stomach, endoscopic non-superficial type, deep tumor invasion in the gastric wall, and t(11;18)/API2-MALT1 translocation[6,7,21,22,26].

| Score | Lymphoid infiltrate | LEL | Stromal changes | Clinical significance |

| CR | Absent or scattered plasma cells and small lymphoid cells in the LP | Absent | Normal or empty LP and/or fibrosis | Complete remission |

| pMRP | Aggregates of lymphoid cells or lymphoid nodules in LP/MM and/or SM | Absent | Empty LP and/or fibrosis | Complete remission |

| rRD | Dense, diffuse or nodular extending around glands in the LP | Focal LEL or absent | Focal empty LP and/or fibrosis | Partial remission |

| NC | Dense, diffuse or nodular | Present, “may be absent” | No changes | Stable disease or progressive disease |

In a systematic review of the data from 32 published studies that included 1408 patients with gastric MALT lymphoma, the CR rate after H. pylori eradication was 78%[6]. Recently, we confirmed excellent long-term outcomes of the disease after H. pylori eradication by a large-scale multicenter study of 420 Japanese patients with gastric MALT lymphoma[7]. In the study, CR was achieved by H. pylori eradication in 77% of patients. During the follow-up periods of up to 14.6 years (mean 6.5 years, median 6.04 years), treatment failure was observed in 9% of patients (37 patients; 10 relapse, 27 progression). Probabilities of freedom from treatment failure, overall survival and event-free survival after 10 years were 90%, 95% and 86%, respectively. Table 3 summarizes 28 previously published studies that included more than 20 patients initially treated by H. pylori eradication[7]. In the 28 studies, CR was achieved in 1361 of 1877 patients (73%), Progressive disease (PD) was observed in 17 of 1576 patients (1.1%), relapse was recorded in 60 of 1203 CR patients (4.9%), and treatment failure (PD or relapse) was found in 118 of all 1877 patients (6.3%). These data are almost similar to those in our multicenter study[7], except for PD rate (1.1% vs 6.4%).

| Author, yr | Patients | CR cases | Median FW (yr) | PD | Relapse | Treatment failure1 |

| Hancock et al, 2009 | 199 | 92 (46) | ND | ND | ND | 25 (13) |

| Wündisch et al, 2006 | 193 | 146 (76) | 2.3 | 0 | 5 (3.1) | 5 (2.6) |

| Wündisch et al, 2005 | 120 | 96 (80) | 6.3 | 0 | 3 (3.1) | 3 (2.5) |

| Stathis et al, 2009 | 102 | 66 (65) | 6.3 | ND | ND | 16 (16) |

| Kim et al, 2007 | 99 | 84 (85) | 3.4 | 0 | 5 (5.9) | 5 (5.1) |

| Nakamura et al, 2005 | 96 | 62 (65) | 3.2 | 7 (7.3) | 4 (6.4) | 11 (11) |

| Hong et al, 2006 | 90 | 85 (94) | 3.8 | 0 | 8 (9.4) | 8 (8.9) |

| Fischbach et al, 2004 | 88 | 73 (83) | 3.8 | 2 (2.3) | 4 (5.5) | 6 (6.8) |

| Nakamura et al, 2008 | 87 | 57 (66) | 3.5 | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.8) | 2 (2.3) |

| Savio et al, 2000 | 76 | 71 (93) | 2.3 | 0 | 6 (8.5) | 6 (7.9) |

| Terai et al, 2008 | 74 | 66 (89) | 3.9 | 0 | 3 (4.5) | 3 (4.1) |

| Sumida et al, 2009 | 66 | 47 (71) | 3.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Weston et al, 1999 | 58 | 40 (69) | 1.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ono et al, 2010 | 58 | 48 (83) | 6.3 | 2 (3.4) | 1 (2.1) | 3 (5.2) |

| Andriani et al, 2009 | 53 | 42 (79) | 5.4 | 0 | 9 (21) | 9 (17) |

| Akamatsu et al, 2006 | 47 | 30 (64) | 3.1 | 1 (2.1) | 1 (3.4) | 2 (4.3) |

| Pinotti et al, 1997 | 44 | 30 (68) | 1.8 | 0 | 2 (6.7) | 2 (4.6) |

| Urakami et al, 2000 | 44 | 42 (95) | 1.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ruskoné-Fourmestraux et al, 2001 | 44 | 19 (43) | 2.9 | 1 (2.3) | 2 (11) | 3 (6.8) |

| Steinbach et al, 1999 | 34 | 14 (41) | 3.4 | 2 (5.9) | 0 | 2 (5.9) |

| Takenaka et al, 2004 | 33 | 26 (79) | ND | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chen et al, 2005 | 32 | 24 (75) | 5.8 | 0 | 3 (13) | 3 (9.4) |

| Lee et al, 2004 | 28 | 24 (86) | 2.0 | 0 | 1 (4.2) | 1 (3.6) |

| Montalban et al, 2005 | 24 | 22 (92) | 4.6 | 0 | 1 (4.5) | 1 (4.2) |

| de Jong et al, 2001 | 23 | 13 (57) | 3.1 | 1 (4.3) | 0 | 1 (4.4) |

| Raderer et al, 2001 | 22 | 15 (68) | 2.1 | 0 | 1 (6.7) | 1 (4.6) |

| Dong et al, 2008 | 22 | 13 (59) | 1.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Yamashita et al, 2000 | 21 | 14 (67) | 0.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total of above | 1877 | 1361 (73) | 3.3 | 17 (1.12) | 60 (4.93) | 118 (6.3) |

| Nakamura et al[7], 2012 | 420 | 323 (77) | 6.04 | 27 (6.4) | 10 (3.1) | 37 (8.8) |

As for the regimen for H. pylori eradication therapy, proton pump inhibitor (PPI) + clarithromycin-based triple therapy composed of a double dose of a PPI plus clarithromycin and amoxicillin or metronidazole for 7 or 14 d is recommended[26,35]. In the areas where the clarithromycin resistance rate exceeds 15%, use of this drug should be avoided without prior susceptibility testing[35]. A pooled data analysis in 1271 patients with gastric MALT lymphoma from 34 studies showed a successful eradication was achieved in 91% of cases after the first-line treatment, and the eradication rate was extended to 98% after the second-line treatment or more attempts[36].

Several studies have demonstrated that H. pylori eradication therapy is also effective even in cases with gastric DLBCL[37,38]. In those reports, 27%-60% of H. pylori-positive patients with DLBCL in stage I/II1 achieved CR after H. pylori eradication. Not only cases with MALT lymphoma component, but also cases without any evidence of MALT lymphoma responded to eradication therapy[37,38]. Therefore, H. pylori eradication should be tried in H. pylori-positive patients with gastric DLBCL.

The management strategy for the patient with gastric MALT lymphoma who does not respond to H. pylori eradication still remains to be elucidated. While patients with PD or clinically evident relapse should undergo oncological treatment, for patients with persistent histological lymphoma without PD (responding residual disease or no change), a “watch and wait” strategy was recommended up to 24 mo after H. pylori eradication in the EGILS consensus report[26].

As for the second-line oncological treatment, radiotherapy is highly effective in localized cases (stage I/II1)[7,26,33]. While chemotherapy and immunotherapy with rituximab are also effective, these systemic treatments are suitable for cases with an advanced stage[26,33]. Recently, the combination of rituximab and chlorambucil[39] or fludarabine[40] provided excellent responses in patients with MALT lymphoma of variable organs, including gastric cases. Surgical resection is nowadays restricted to the management of cases with perforation or bleeding that cannot be controlled endoscopically[26].

While a large amount of clinical evidence has confirmed the validity of H. pylori eradication as the first-line treatment for gastric MALT lymphoma, there are many choices for the second-line treatments. Because of the indolent behavior of MALT lymphoma, the strategy for patients not responding to H. pylori eradication should be tailored in consideration of the clinical stage and extent of the disease. Despite the recent advances in our understanding of the pathogenesis of gastric MALT lymphoma, there still exist many questions to be answered. Further basic and clinical research is needed to clarify the molecular mechanisms in the development of the disease.

P- Reviewers: Chen XZ, Maluf F, Nakase H S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: Logan S E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Isaacson PG, Chott A, Nakamura S, Müller-Hermelink HK, Harris NL, Swerdlow SH. Extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT lymphoma). WHO Classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC 2008; 214-217. |

| 2. | Amer MH, el-Akkad S. Gastrointestinal lymphoma in adults: clinical features and management of 300 cases. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:846-858. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Yoshino T, Miyake K, Ichimura K, Mannami T, Ohara N, Hamazaki S, Akagi T. Increased incidence of follicular lymphoma in the duodenum. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:688-693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nakamura S, Matsumoto T, Iida M, Yao T, Tsuneyoshi M. Primary gastrointestinal lymphoma in Japan: a clinicopathologic analysis of 455 patients with special reference to its time trends. Cancer. 2003;97:2462-2473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nakamura S, Matsumoto T. Gastrointestinal lymphoma: recent advances in diagnosis and treatment. Digestion. 2013;87:182-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zullo A, Hassan C, Cristofari F, Andriani A, De Francesco V, Ierardi E, Tomao S, Stolte M, Morini S, Vaira D. Effects of Helicobacter pylori eradication on early stage gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:105-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Nakamura S, Sugiyama T, Matsumoto T, Iijima K, Ono S, Tajika M, Tari A, Kitadai Y, Matsumoto H, Nagaya T. Long-term clinical outcome of gastric MALT lymphoma after eradication of Helicobacter pylori: a multicentre cohort follow-up study of 420 patients in Japan. Gut. 2012;61:507-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Wotherspoon AC, Ortiz-Hidalgo C, Falzon MR, Isaacson PG. Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis and primary B-cell gastric lymphoma. Lancet. 1991;338:1175-1176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1293] [Cited by in RCA: 1201] [Article Influence: 35.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Parsonnet J, Hansen S, Rodriguez L, Gelb AB, Warnke RA, Jellum E, Orentreich N, Vogelman JH, Friedman GD. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1267-1271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1287] [Cited by in RCA: 1229] [Article Influence: 39.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nakamura S, Yao T, Aoyagi K, Iida M, Fujishima M, Tsuneyoshi M. Helicobacter pylori and primary gastric lymphoma. A histopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 237 patients. Cancer. 1997;79:3-11. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Nakamura S, Matsumoto T, Ye H, Nakamura S, Suekane H, Matsumoto H, Yao T, Tsuneyoshi M, Du MQ, Iida M. Helicobacter pylori-negative gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma: a clinicopathologic and molecular study with reference to antibiotic treatment. Cancer. 2006;107:2770-2778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Asano N, Iijima K, Terai S, Jin X, Ara N, Chiba T, Fushiya J, Koike T, Imatani A, Shimosegawa T. Eradication therapy is effective for Helicobacter pylori-negative gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2012;228:223-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Du MQ. MALT lymphoma: many roads lead to nuclear factor-κb activation. Histopathology. 2011;58:26-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hussell T, Isaacson PG, Crabtree JE, Spencer J. The response of cells from low-grade B-cell gastric lymphomas of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue to Helicobacter pylori. Lancet. 1993;342:571-574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 571] [Cited by in RCA: 515] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hussell T, Isaacson PG, Crabtree JE, Spencer J. Helicobacter pylori-specific tumour-infiltrating T cells provide contact dependent help for the growth of malignant B cells in low-grade gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. J Pathol. 1996;178:122-127. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Greiner A, Knörr C, Qin Y, Sebald W, Schimpl A, Banchereau J, Müller-Hermelink HK. Low-grade B cell lymphomas of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT-type) require CD40-mediated signaling and Th2-type cytokines for in vitro growth and differentiation. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:1583-1593. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Knörr C, Amrehn C, Seeberger H, Rosenwald A, Stilgenbauer S, Ott G, Müller Hermelink HK, Greiner A. Expression of costimulatory molecules in low-grade mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue-type lymphomas in vivo. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:2019-2027. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | D'Elios MM, Amedei A, Manghetti M, Costa F, Baldari CT, Quazi AS, Telford JL, Romagnani S, Del Prete G. Impaired T-cell regulation of B-cell growth in Helicobacter pylori--related gastric low-grade MALT lymphoma. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:1105-1112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Craig VJ, Cogliatti SB, Arnold I, Gerke C, Balandat JE, Wündisch T, Müller A. B-cell receptor signaling and CD40 ligand-independent T cell help cooperate in Helicobacter-induced MALT lymphomagenesis. Leukemia. 2010;24:1186-1196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Munari F, Lonardi S, Cassatella MA, Doglioni C, Cangi MG, Amedei A, Facchetti F, Eishi Y, Rugge M, Fassan M. Tumor-associated macrophages as major source of APRIL in gastric MALT lymphoma. Blood. 2011;117:6612-6616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Nakamura S, Ye H, Bacon CM, Goatly A, Liu H, Banham AH, Ventura R, Matsumoto T, Iida M, Ohji Y. Clinical impact of genetic aberrations in gastric MALT lymphoma: a comprehensive analysis using interphase fluorescence in situ hybridisation. Gut. 2007;56:1358-1363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Liu H, Ye H, Ruskone-Fourmestraux A, De Jong D, Pileri S, Thiede C, Lavergne A, Boot H, Caletti G, Wündisch T. T(11; 18) is a marker for all stage gastric MALT lymphomas that will not respond to H. pylori eradication. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1286-1294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 302] [Cited by in RCA: 272] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chuang SS, Lee C, Hamoudi RA, Liu H, Lee PS, Ye H, Diss TC, Dogan A, Isaacson PG, Du MQ. High frequency of t(11; 18) in gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas in Taiwan, including one patient with high-grade transformation. Br J Haematol. 2003;120:97-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Chanudet E, Ye H, Ferry J, Bacon CM, Adam P, Müller-Hermelink HK, Radford J, Pileri SA, Ichimura K, Collins VP. A20 deletion is associated with copy number gain at the TNFA/B/C locus and occurs preferentially in translocation-negative MALT lymphoma of the ocular adnexa and salivary glands. J Pathol. 2009;217:420-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Honma K, Tsuzuki S, Nakagawa M, Tagawa H, Nakamura S, Morishima Y, Seto M. TNFAIP3/A20 functions as a novel tumor suppressor gene in several subtypes of non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Blood. 2009;114:2467-2475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 235] [Cited by in RCA: 245] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ruskoné-Fourmestraux A, Fischbach W, Aleman BM, Boot H, Du MQ, Megraud F, Montalban C, Raderer M, Savio A, Wotherspoon A. EGILS consensus report. Gastric extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of MALT. Gut. 2011;60:747-758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 245] [Cited by in RCA: 237] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Montalbán C, Castrillo JM, Abraira V, Serrano M, Bellas C, Piris MA, Carrion R, Cruz MA, Laraña JG, Menarguez J. Gastric B-cell mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma. Clinicopathological study and evaluation of the prognostic factors in 143 patients. Ann Oncol. 1995;6:355-362. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Taal BG, Boot H, van Heerde P, de Jong D, Hart AA, Burgers JM. Primary non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the stomach: endoscopic pattern and prognosis in low versus high grade malignancy in relation to the MALT concept. Gut. 1996;39:556-561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Fischbach W, Dragosics B, Kolve-Goebeler ME, Ohmann C, Greiner A, Yang Q, Böhm S, Verreet P, Horstmann O, Busch M. Primary gastric B-cell lymphoma: results of a prospective multicenter study. The German-Austrian Gastrointestinal Lymphoma Study Group. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1191-1202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Nakamura S, Akazawa K, Yao T, Tsuneyoshi M. A clinicopathologic study of 233 cases with special reference to evaluation with the MIB-1 index. Cancer. 1995;76:1313-1324. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Rohatiner A, d’Amore F, Coiffier B, Crowther D, Gospodarowicz M, Isaacson P, Lister TA, Norton A, Salem P, Shipp M. Report on a workshop convened to discuss the pathological and staging classifications of gastrointestinal tract lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 1994;5:397-400. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Matsumoto T, Nakamura S, Esaki M, Yada S, Moriyama T, Yanai S, Hirahashi M, Yao T, Iida M. Double-balloon endoscopy depicts diminutive small bowel lesions in gastrointestinal lymphoma. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:158-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines). Non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas, Version 2. 2013; Available from: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nhl.pdf. |

| 34. | Copie-Bergman C, Gaulard P, Lavergne-Slove A, Brousse N, Fléjou JF, Dordonne K, de Mascarel A, Wotherspoon AC. Proposal for a new histological grading system for post-treatment evaluation of gastric MALT lymphoma. Gut. 2003;52:1656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, Atherton J, Axon AT, Bazzoli F, Gensini GF, Gisbert JP, Graham DY, Rokkas T. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection--the Maastricht IV/Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2012;61:646-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1719] [Cited by in RCA: 1591] [Article Influence: 122.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 36. | Zullo A, Hassan C, Andriani A, Cristofari F, De Francesco V, Ierardi E, Tomao S, Morini S, Vaira D. Eradication therapy for Helicobacter pylori in patients with gastric MALT lymphoma: a pooled data analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1932-197; quiz 1938. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Nakamura S, Matsumoto T, Suekane H, Takeshita M, Hizawa K, Kawasaki M, Yao T, Tsuneyoshi M, Iida M, Fujishima M. Predictive value of endoscopic ultrasonography for regression of gastric low grade and high grade MALT lymphomas after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Gut. 2001;48:454-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Kuo SH, Yeh KH, Wu MS, Lin CW, Hsu PN, Wang HP, Chen LT, Cheng AL. Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy is effective in the treatment of early-stage H pylori-positive gastric diffuse large B-cell lymphomas. Blood. 2012;119:4838-444; quiz 5057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Zucca E, Conconi A, Laszlo D, López-Guillermo A, Bouabdallah R, Coiffier B, Sebban C, Jardin F, Vitolo U, Morschhauser F. Addition of rituximab to chlorambucil produces superior event-free survival in the treatment of patients with extranodal marginal-zone B-cell lymphoma: 5-year analysis of the IELSG-19 Randomized Study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:565-572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Salar A, Domingo-Domenech E, Estany C, Canales MA, Gallardo F, Servitje O, Fraile G, Montalbán C. Combination therapy with rituximab and intravenous or oral fludarabine in the first-line, systemic treatment of patients with extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type. Cancer. 2009;115:5210-5217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |