INTRODUCTION

Angiosarcoma is a rare tumor that account for less than 1% of all sarcomas[1], and only 2% of all primary tumors of liver[2]. Although it is rarely observed, it is the third most common primary malignant liver tumor[3]. Clinical diagnosis is usually difficult because the symptoms and signs are unspecific, and tumors are difficult to differentiate from other hepatic tumors radiologically[4]. Moreover, although tissue is required for diagnosis, the rate of diagnosis by needle biopsy is not high[5]. Angiosarcoma progresses rapidly and has a poor prognosis[6]. Treatment guidelines have not been issued as yet, however, we think it important to diagnose angiosarcoma as early as possible. Herein, we report a case of primary hepatic angiosarcoma, which was manifested as recurrent hemoperitoneum.

CASE REPORT

A 73-year-old woman presented with epigastric pain and right shoulder pain. She had suffered from hypertension for several years, but no other past medical histories. On physical examination, the patient appeared with acutely ill and had right upper quadrant pain and tenderness. A complete blood count and blood chemistry were: hemoglobin 11.3 g/dL, hematocrit 34.2%, white blood count 18 400/mm3 (segmented neutrophil 86.6%), platelet 284 000/mm3, total protein/albumin 5.7/3.8 g/dL, total bilirubin 0.7 mg/dL, direct bilirubin 0.1 mg/dL, AST 24 IU/L, ALT 36 U/L, ALP 49 IU/L, G-GTP 59 IU/L, PT 13.2 s, and amylase 60. Tumor markers such as alpha feto-protein, CEA, CA19-9 and CA125 were all within normal limit.

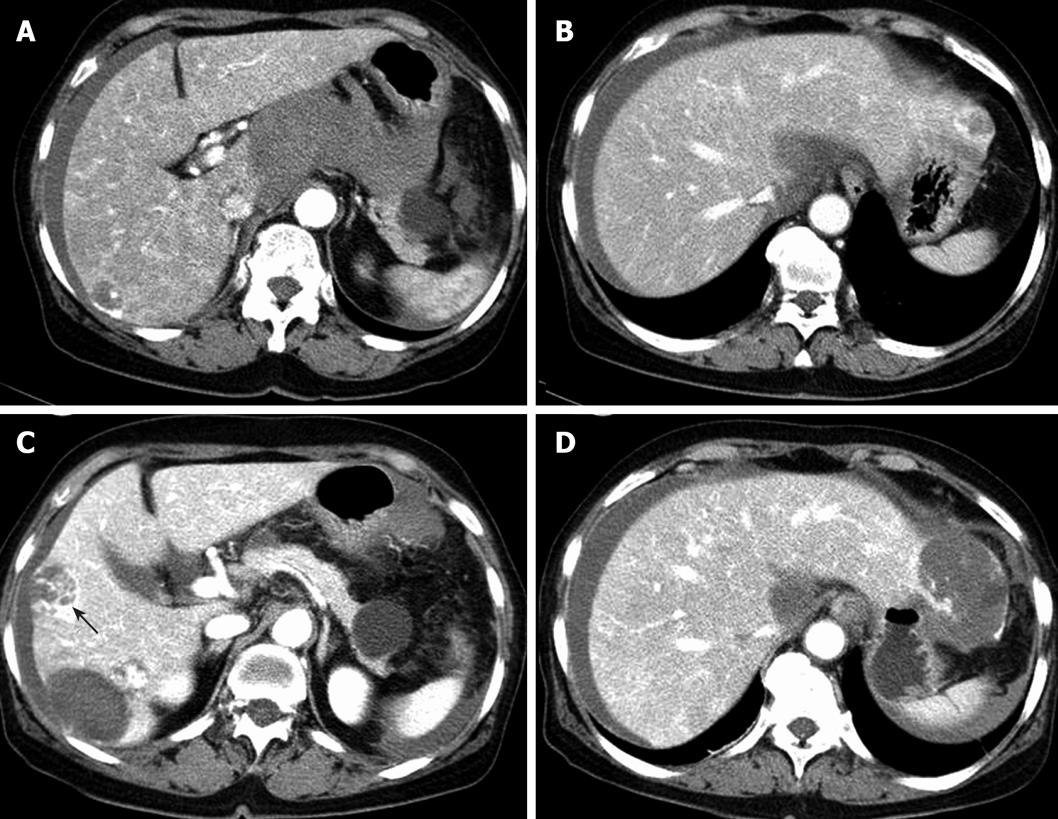

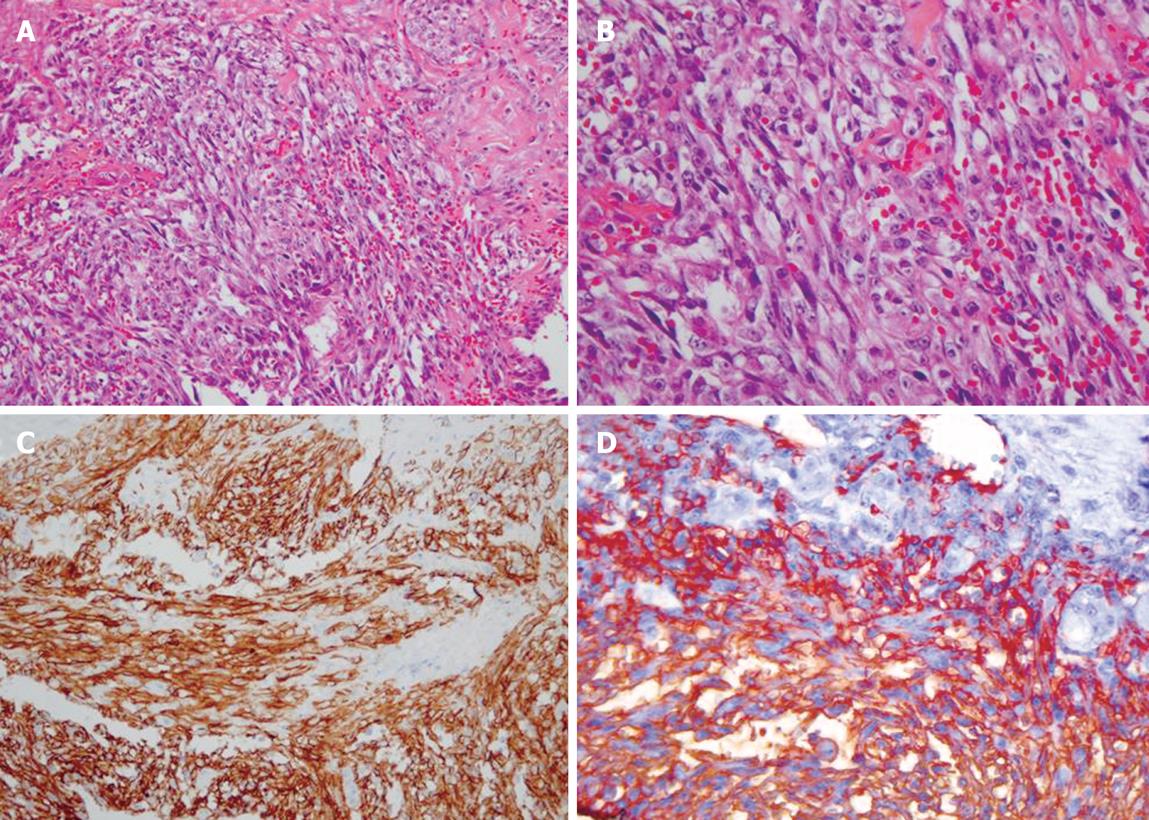

Computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen showed multiple hypervascular masses in the liver and a large amount of hematoma in lesser sac. We thought that a mass in the caudate lobe had ruptured into the abdominal cavity and had caused hemoperitoneum (Figure 1A and B). Transarterial embolization was performed. Her condition then stabilized and she was discharged. However, one month later she revisited the emergency room with identical symptoms. Abdominal CT revealed rupture of two hypervascular mass in the right hepatic lobe. After the 2nd transarterial embolization, she became destabilized. A sono-guided needle biopsy was performed but we failed to confirm a specific diagnosis. Five days after discharge, she visited the emergency room again with the same symptoms. Abdominal CT showed interval increased size of low attenuated lesions with peripheral nodular enhancement in the left lateral and right lobe. One of them shows septum-like and peripheral enhancement within the mass (Figure 1C and C). Transarterial embolization was performed repeatedly (Figure 2) but her vital signs were unstable and bleeding of the hepatic mass continued. On the 8th d after the 3rd embolization, we decided to resect the left hepatic lobe, which showed active bleeding on abdominal CT scan. In operation, there was much blood in the abdominal cavity. The rupture of hepatic mass at segment 2 and 3 was noted. So we decided to resect the left lateral segment which contained the bleeding mass. However, the intra-abdominal bleeding continued and she finally died of disseminated intravascular coagulation. The postoperative surgical specimen showed a great amount of atypical cells forming solid sheets filled with red blood cells (RBCs), which is suggestive of hepatic angiosarcoma. Immunohistochemical staining for CD31 and CD34 showed diffuse strong positive expression (Figure 3).

Figure 1 Initial abdominal computed tomography images.

A and B: A large amount of hematoma in lesser sac and a lowly attenuated nodular lesion with peripheral globular enhancement in the left lobe. Abdominal CT images after 1 mo; C and D: increased size of lowly attenuated lesions in the right lobe and the left lateral lobe. One showing septum-like appearance and peripheral enhancement within the mass (black arrow).

Figure 2 Transarterial embolization images.

A: A large tumor stain in the lateral segment of left lobe (arrows); B: Post-embolization angiogram showing no remained tumor stain.

Figure 3 Pathologic findings.

A and B: Atypical cells forming solid sheets filled with RBCs (HE stain, × 200, × 400, respectively); C and D: Immunohistochemical staining for CD31 and CD34 showing diffuse strong positive expression (× 200, × 400, respectively).

DISCUSSION

Angiosarcoma (AS) can originate from the endothelia of lymphatics or blood vessels and is a rarely encountered type of soft tissue sarcoma[7]. Angiosarcoma has a predilection for cutaneous sites in the head and neck region of elderly male patients[8]. Moreover, despite its rarity, hepatic angiosarcoma is the third most common primary malignant tumor of the liver[3]. Environmental toxins are suggested to be the etiology of AS, for example, the industrial intermediates thorotrast and vinyl chloride and agricultural insecticides are associated with AS[910], as do the anabolic steroids and synthetic estrogens[1112]. However, the majority of hepatic angiosarcomas are not related to the above agents.

Angiosarcoma usually presents with nonspecific symptoms, such as abdominal pain, weight loss and general weakness[2]. Its physical findings are ascites, hepatomegaly and jaundice. In this case, the main symptoms were abdominal and right shoulder pain.

Primary hepatic angiosarcoma is difficult to differentiate from other vascular tumors of the liver using radiographic techniques. On ultrasound, single or multiple masses are demonstrated with different echotextures due to different levels of necrosis and hemorrhage[13]. On nonenhanced helical CT, tumors present as multiple hypodense masses or as a large solitary hypodense mass. In enhanced view, some of the masses are hyperattenuated while others remain hypoattenuated[14]. Within hyperattenuated mass areas, an area of hypoattenuation may be seen, which reflect areas of necrosis and/or old hemorrhage. The delayed scans of some lesions show progressive enhancement over minutes due to the vascular nature of the tumor[15]. In this case, multiple heterogeneous and lowly attenuated lesions with septum like structures were observed on CT scans. Arterioportal shunting is not seen in hemangiomas, and if it is present, it favors a diagnosis of angiosarcoma[16]. The magnetic resonance imaging findings of angiosarcomas and hemangiomas are also similar. Liver biopsies in angiosarcoma patients are accompanied by risks of morbidity and mortality, because the vascular nature of the tumor and its tendency to hemorrhage make the percutaneous biopsy dangerous[2]. Microscopic features include sinusoidal and solid patterns. The sinusoidal pattern is characterized by the proliferation of single or multilayered tumor cell along sinusoids which show sinusoidal dilation, atrophy of liver cell cords. The solid pattern is composed of spindle and polyhedral cells, which form a solid tumor nest without significant vascular spaces[17]. The immunohistochemical staining for CD31 and factor VIII related antigen can aid diagnosis[18].

The treatment of hepatic angiosarcoma has not been defined because of its rarity and associated mortality. The median survival is 6 mo if not treated and only 3% of patients live longer than 2 years[2]. Hepatic resection is indicated when the tumor is localized to one lobe and the remainder of the liver is relatively normal[19]. However, patients meeting these criteria are extremely rare. Timaran et al[20] reported a case of hepatic angiosarcoma with a long postoperative survival after complete surgical resection of the tumor.

Radiation therapy to the liver has been used to palliate liver metastases[21], but soft tissue sarcoma is relatively radioresistant and the dosage required to treat sarcoma is higher than the tolerable dose[22].

Chemotherapy plays a role in the treatment of soft tissue sarcomas. The drugs that show some activity are: alkylating agents, vincristine, actinomycin, adriamycin, and DTIC (Dimethyl triazeno imidazole carboxamide)[23]. Gershon et al[2] reported that adriamycin produced two definite responses, as documented by angiography. Dannaher et al[24] reported that chemotherapy produced an objective improvement in three of four patients and stabilized the disease in one patient. Transarterial chemoembolization is useful for preventing acute arterial bleeding from the liver. Catheter directed embolization allows planning and well structured surgery without the need of emergency liver surgery, which carries high risks of morbidity and lethality[25]. In this case, the patient underwent hepatic resection after transarterial chemoembolization due to acute arterial bleeding in the liver. Liver transplantation has been described in a patient with an unresectable primary hepatic tumor. However, no patient has been reported to survive for longer than 28 mo because of the high recurrence rate of hepatic angiosarcoma[26].

When a ruptured mass causes the spillage of tumor cells into the peritoneal cavity and diffuse sarcomatosis in the peritoneum, the angiosarcomatous lesions subsequently formed induce diffuse and severe hemorrhage, thus appearing to be a leading cause of death[25].

The prognosis of patients with hepatic angiosarcoma is dismal[6]. Although hepatic angiosarcoma is usually found to be unresectable at the time of diagnosis, early diagnosis and complete resection of the tumor may reduce the mortality associated with this disease. In conclusion, we advise that the possibility of angiosarcoma should be considered when a bleeding hepatic mass is encountered.