Published online Oct 7, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i37.6017

Revised: May 25, 2006

Accepted: June 14, 2006

Published online: October 7, 2006

AIM: To compare the efficacy and tolerability of S-pantoprazole (20 mg once a day) versus racemic Pantoprazole (40 mg once a day) in the treatment of gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD).

METHODS: This multi-centre, randomized, double-blind clinical trial consisted of 369 patients of either sex suffering from GERD. Patients were randomly assigned to receive either one tablet (20 mg) of S-pantoprazole once a day (test group) or 40 mg racemic pantoprazole once a day (reference group) for 28 d. Patients were evaluated for reduction in baseline on d 0, GERD symptom score on d 14 and 28, occurrence of any adverse effect during the course of therapy. Gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy was performed in 54 patients enrolled at one of the study centers at baseline and on d 28.

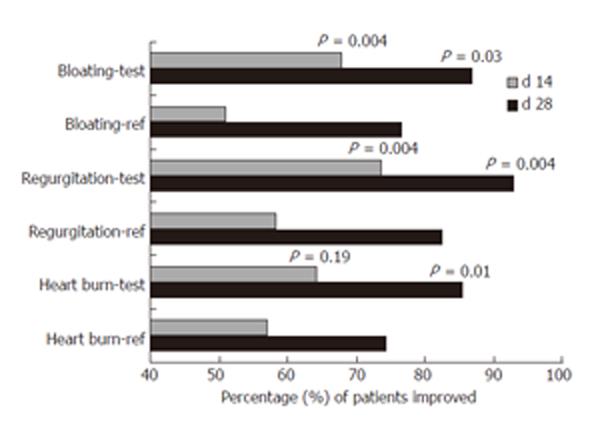

RESULTS: Significant reduction in the scores (mean and median) for heart burn (P < 0.0001), acid regurgitation (P < 0.0001), bloating (P < 0.0001), nausea (P < 0.0001) and dysphagia (P < 0.001) was achieved in both groups on d 14 with further reduction on continuing the therapy till 28 d. There was a statistically significant difference in the proportion of patients showing improvement in acid regurgitation and bloating on d 14 and 28 (P = 0.004 for acid regurgitation; P = 0.03 for bloating) and heart burn on d 28 (P = 0.01) between the two groups, with a higher proportion in the test group than in the reference group. Absolute risk reductions for heartburn/acid regurgitation/bloating were approximately 15% on d 14 and 10% on d 28. The relative risk reductions were 26%-33% on d 14 and 15% on d 28. GI endoscopy showed no significant difference in healing of esophagitis (P = 1) and gastric erosions (P = 0.27) between the two groups. None of the patients in either group reported any adverse effect during the course of therapy.

CONCLUSION: In GERD, S-pantoprazole (20 mg) is more effective than racemic pantoprazole (40 mg) in improving symptoms of heartburn, acid regurgitation, bloating and equally effective in healing esophagitis and gastric erosions. The relative risk reduction is 15%-33%. Both drugs are safe and well tolerated.

- Citation: Pai VG, Pai NV, Thacker HP, Shinde JK, Mandora VP, Erram SS. Comparative clinical trial of S-pantoprazole versus racemic pantoprazole in the treatment of gastro-esophageal reflux disease. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(37): 6017-6020

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i37/6017.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i37.6017

The primary treatment goals in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) are relief of symptoms, prevention of symptom relapse, healing of erosive esophagitis, and prevention of complications of esophagitis[1]. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) block the final step in acid production and hence are the most effective inhibitors of acid secretion[2]. Recent advances in analytical methods for the separation of enantiomers of PPIs have led to a considerable interest in the stereoselective pharmacokinetics of PPI enantiomers[3].

Pantoprazole, a selective and long acting PPI, is a chiral sulfoxide that is used clinically as a racemic mixture of S-pantoprazole and R (+) pantoprazole. The pharmacokinetics of R and S isomers of pantoprazole vary widely in extensive and poor metabolizers[4]. The use of a single isomer avoids this variation and offers predictable pharmacokinetics. Animal studies have shown that S-pantoprazole is more potent (1.5 to 1.9 times) and effective (3 to 4 times) than racemate in inhibiting gastric lesions in different pre-clinical models[3,5], suggesting that in human patients 20 mg of S-pantoprazole would be at least equivalent in efficacy to 40 mg of racemic pantoprazole. The present study was to compare the efficacy and tolerability of S-pantoprazole (20 mg) versus racemic pantoprazole (40 mg) in the treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GERD) in adult patients.

S-pantoprazole was synthesized by Emcure Pharmaceuticals Ltd. Tablets of S-pantoprazole (20 mg) and racemic pantoprazole (40 mg) were provided by the same source in coated opaque packets containing 28 tablets each without labeling the identity of the contents.

This multi-centre, randomized, double blind comparative study permitted by Drugs Controller General of India (DCGI) was conducted in compliance with the ‘Guidelines for Clinical Trials on Pharmaceutical Products in India-GCP Guidelines’ issued by the Central Drugs Standard Control Organization, Ministry of Health, Government of India (http://www.cdsco.nic.in/html/GCP1.html). The Ethical Committee approval was taken from Sharada Clinic Ethical Committee, Karad for Dr. S Erram, Independent Ethical Committee for Dr. H Thacker, Independent Ethical Committee of Surya Hospital, Pune for Dr. V Pai, Dr. V Mandora and Dr. J Shinde. Written informed consent was obtained from the subjects. The study was initiated on November 7, 2004 and completed on February 25, 2005.

Patients of either sex, aged 18-65 years, with clinically confirmed GERD, were enrolled in the study after providing written informed consent. Patients with known hypersensitivity to pantoprazole and any major hematologic, hepatic, metabolic, gastrointestinal or endocrine disorder requiring any other anti-GERD medication and women who were pregnant or lactating or child bearing potential and not practicing effective method of contraception were excluded from the study.

Patients were randomized in blocks of ten, as per the computer generated randomization chart (http://www.randomization.com) into two treatment groups: one group receiving 20 mg S-pantoprazole once daily for 28 d (test group) while the other group receiving 40 mg racemic pantoprazole once daily (reference group) for the same period. The identity of the treatment allocated was unknown to either investigators or patients. The reference and test medications had a similar appearance, shape and size and could not be distinguished from each other based on their external appearance. All the patients completed the 28 d therapy during which they were followed up twice on d 14 and 28. Medication compliance was checked by counting the number of tablets left in the packet, if any.

Heartburn, regurgitation and dysphagia are symptoms of GERD. Although nausea and bloating are symptoms of dyspepsia which can be an overlapping condition in patients with GERD, this study included patients with symptoms of nausea and bloating also in order to capture the overall clinical benefit. The severity of heartburn, acid regurgitation, bloating and nausea was scored as follows: 0 = none, no symptom; 1 = mild, occasional symptoms that did not affect normal activities; 2 = moderate, frequent symptoms or symptoms that affected normal activities; 3 = severe, constant symptoms. The severity of dysphagia was scored as follows: 0 = normal; 1 = occasional sticking of solids; 2 = swallowing semisolids and Pureed food; 3 = swallowing liquids only. Scores were recorded for all the patients at the initiation of the study and then on d 14 and 28. Improvement in symptoms was defined as reduction in baseline symptom score. Assessment of within-group efficacy was done by comparing symptom scores on d 14 and 28 with baseline value on d 0 of the study. Assessment of between-group efficacy was done by comparing the proportions of patients showing improvement in symptoms in each group. GI endoscopy was done in 54 patients enrolled at one of the study centers on d 0 and 28. Tolerability profile was assessed by comparing the incidence of possible drug-related adverse effects in each group on d 14 and 28 of the study.

The results were analyzed using Fisher’s exact test (two sided) for difference in proportions, Friedman’s test (non-parametric repeated measures ANOVA) for comparison of between-days score (variation amongst column medians). For this, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Individual differences between columns (d 0 vs d 14 and d 0 vs d 28) were assessed by Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. The GraphPad InStat (version 3.06, 32 bit for Windows, September 11, 2003, GraphPad Software, San Diego California USA, http://www.graphpad.com) and WINPEPI suite (Abramson JH (2004) WINPEPI (PEPI-for-Windows) computer programs for epidemiologists as well as Epidemiologic Perspectives & Innovations (2004, 1:6) softwares were used for statistical analysis. UBC clinical significance calculator (from http://www.healthcare.ubc.ca/calc/clinsig.html) was used to calculate the absolute risk reduction (ARR), relative risk reduction (RRR) and number needed to treat (NNT). ARR is the absolute arithmetic difference in rates of bad outcomes between experimental and control participants in a trial, calculated as experimental event rate minus control event rate. RRR is the proportional reduction in rates of bad outcomes between experimental and control participants in a trial, calculated as experimental event rate minus control event rate divided by control event rate. NNT is the number of patients who need to be treated to achieve one additional favorable outcome, calculated as 1/ARR.

Three hundred and sixty-nine patients (229 males and 140 females) with symptoms of GERD were enrolled in the study after providing written informed consent. Baseline demographic variables of the two groups are shown in Table 1. There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups at baseline.

| Variable | Reference group | Test group |

| n | 182 | 187 |

| Male: Female | 115:67 | 114:73 |

| Mean age ± SD (yr) | 42.3 ± 11.7 | 42 ±12.3 |

No significant differences were present in the baseline symptom scores in both groups. In both treatment groups, significant reductions in the mean and median scores for heart burn (P < 0.0001), acid regurgitation (P < 0.0001), bloating (P < 0.0001), nausea (P < 0.0001) and dysphagia (P < 0.001) were achieved on d 14 with further reduction on continuing the therapy till d 28 (Table 2). The percentage of patients in the reference group, achieving improvement in heart burn, acid regurgitation, bloating, nausea and dysphagia was 57.0%, 58.2%, 51.0%, 66.4% and 58.6% respectively at the end of 14 d therapy, and 74.4%, 82.4%, 76.5%, 81.3% and 79.3% respectively at the end of 28 d therapy. The percentage of patients in the test group, achieving improvement in heart burn, acid regurgitation, bloating, nausea and dysphagia was 64.3%, 73.5%, 67.8%, 72.7% and 67.8% respectively at the end of 14 d of therapy, and 85.5%, 92.9%, 86.7%, 81.3% and 84.7% respectively at the end of 28 d of therapy. There was a statistically significant difference in the proportion of patients showing improvement in acid regurgitation and bloating on d 14 and 28 (P = 0.004 for acid regurgitation; P = 0.03 for bloating), and heart burn on d 28 (P = 0.01) between the two groups, with a higher proportion in the test group than in the reference group (Table 3, Figure 1).

| Symptoms | d 0 | d 14 | d 28 | P3 | ||||

| Ref | Test | Ref | Test | Ref | Test | |||

| Heart burn | Mean ± SD | 1.8 ± 0.8 | 1.9 ± 0.8 | 1.2 ± 0.8 | 1.2 ± 0.9 | 0.6 ± 0.9 | 0.6 ± 0.8 | < 0.0001 |

| Median (Percentile 25th, 75th) | 2 (1.2) | 2 (1.3) | 1 (1.2)2 | 1 (0.5.2)1 | 0 (0.1)2 | 0 (0.1)1 | ||

| Regurgitation | Mean ± SD | 1.6 ± 0.9 | 1.7 ± 0.9 | 1.1 ± 0.8 | 1 ± 0.8 | 0.5 ± 0.8 | 0.4 ± 0.6 | < 0.0001 |

| Median (Percentile 25th, 75th) | 2 (1.2) | 2 (1.2) | 1 (0.2)2 | 1 (0.2)1 | 0 (0.1)2 | 0 (0.1)1 | ||

| Bloating | Mean ± SD | 1.4 ± 0.9 | 1.4 ± 1 | 0.9 ± 0.9 | 0.8 ± 0.8 | 0.5 ± 0.8 | 0.3 ± 0.6 | < 0.0001 |

| Median (Percentile 25th, 75th) | 1 (1.2) | 2 (1.2) | 1 (0.2)2 | 1 (1.2)1 | 0 (0.1)2 | 1 (1.1)1 | ||

| Nausea | Mean ± SD | 1.4 ± 1 | 1.3 ± 1 | 0.8 ± 0.9 | 0.7 ± 0.8 | 0.4 ± 0.8 | 0.4 ± 0.7 | < 0.0001 |

| Median (Percentile 25th, 75th) | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2)2 | 0 (0.1)1 | 0 (0.0.25)2 | 0 (0.1)1 | ||

| Dysphagia | Mean ± SD | 0.3 ± 0.6 | 0.5 ± 0.8 | 0.2 ± 0.6 | 0.2 ± 0.5 | 0.1 ± 0.4 | 0.1 ± 0.4 | < 0.001 |

| Median (Percentile 25th, 75th) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0)1 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0)1 | ||

| Decrease compared to baseline (d 0) in score | Patients showing improvement in symptoms (n) | |||||||||||

| Heart burn | Regurgitation | Bloating | ||||||||||

| On d 14 | On d 28 | On d 14 | On d 28 | On d 14 | On d 28 | |||||||

| Ref | Test | Ref | Test | Ref | Test | Ref | Test | Ref | Test | Ref | Test | |

| Decrease by 1 | 89 | 93 | 56 | 71 | 90 | 111 | 76 | 86 | 62 | 81 | 69 | 65 |

| Decrease by 2 | 9 | 21 | 61 | 67 | 6 | 12 | 52 | 52 | 11 | 14 | 36 | 38 |

| Decrease by 3 | 0 | 1 | 11 | 15 | 0 | 2 | 8 | 20 | 3 | 2 | 9 | 21 |

| Patients who improved (n) | 98 | 115 | 128 | 153 | 96 | 125 | 136 | 158 | 76 | 97 | 114 | 124 |

| Patients with symptoms (n) | 172 | 179 | 172 | 179 | 165 | 170 | 165 | 170 | 149 | 143 | 149 | 143 |

| Fisher’s test, P | 0.19 | 0.01 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.03 | ||||||

Of the 54 patients who underwent GI endoscopy, baseline findings of esophagitis and erosions were present in 17 (68%) and 6 (2.4%) patients out of 25 patients in the reference group and 21 (72.4%) and 2 (0.7%) patients out of 29 patients in the test group respectively. Twenty-eight days after therapy, esophagitis and erosions were present in 7 (28%) and 6 (2.4%) patients out of 25 patients in the reference group and 9 (31%) and 3 (1.03%) patients out of 29 patients in the test group respectively. There was no significant difference in both treatment groups in healing of esophagitis (P = 1) and erosions (P = 0.27) (Table 5).

| Number of patients with findings (n) | ||||

| d 0 | d 28 | |||

| Esophagitis | Erosions | Esophagitis | Erosions | |

| Ref | 17 | 6 | 7 | 6 |

| Test | 21 | 2 | 7 | 3 |

| Fisher’s test, P | 0.77 | 0.12 | 1 | 0.27 |

None of the patients in either group reported any adverse effect during the course of the study. Both drugs were well tolerated.

All PPIs are chiral compounds. Chirality can introduce marked selectivity and specificity into the way the drug is handled by the body and how the compound interacts with the receptor or enzyme binding sites in some cases. Overall, this may lead to variations in pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties and differences in safety and toxicity profiles[6].

The present study showed that symptoms of GERD viz heart burn, acid regurgitation, bloating, nausea and dysphagia improved significantly in both treatment groups. The results also showed that a significantly higher proportion of patients treated with 20 mg S-pantoprazole achieved improvement in heart burn, acid regurgitation and bloating as compared to patients treated with 40 mg racemic pantoprazole (Table 3, Figure 1). The absolute risk reduction was approximately 15% on d 14 and 10% on d 28. The relative risk reduction was approximately 15% on d 28 and at least 26% on d 14. This translates to a NNT of approximately 6-7 patients on d 14 and 9-10 patients on d 28 (Table 4). The findings of GI endoscopy showed that 20 mg S-pantoprazole was equally effective compared to 40 mg racemic pantoprazole in healing esophagitis (P = 1) and gastric erosions (P = 0.27). Both drugs were well tolerated with no adverse effects. These findings confirm that S-pantoprazole is the more active component of racemic pantoprazole that can be used even at half the dose of racemate to achieve a better efficacy in the treatment of GERD.

| Symptoms, d | Absolute risk reduction1 (95% CI for difference in improvement) (%) | RRR (%) | NNT |

| Heartburn, d 28 | + 11.1 (2.7-19.4) | 15 | 9 |

| Acid regurgitation, d 14 | + 15.3 (5.3-25.0) | 26 | 7 |

| Acid regurgitation, d 28 | + 10.5 (3.6-17.5) | 13 | 10 |

| Bloating, d 14 | + 16.8 (5.7-27.9) | 33 | 6 |

| Bloating, d 28 | + 10.2 (1.4-19.0) | 13 | 10 |

In summary, 20 mg S-pantoprazole is more effective than 40 mg racemic pantoprazole in improving symptoms of heart burn, acid regurgitation, bloating of GERD. Both drugs are safe and well tolerated.

The authors thank Emcure Pharmaceuticals Ltd for providing S-pantoprazole and racemic pantoprazole tablets.

S- Editor Wang GP L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Bi L

| 1. | Heidelbaugh JJ, Nostrant TT, Kim C, Van Harrison R. Management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68:1311-1318. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Sachs G. Proton pump inhibitors and acid-related diseases. Pharmacotherapy. 1997;17:22-37. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Cao H, Wang M, Jia J, Wang Q, Cheng M. Comparison of the effects of pantoprazole enantiomers on gastric mucosal lesions and gastric epithelial cells in rats. Yihu Keji Qikan. 2004;50:1-8. |

| 4. | Tanaka M, Yamazaki H, Hakusui H, Nakamichi N, Sekino H. Differential stereoselective pharmacokinetics of pantoprazole, a proton pump inhibitor in extensive and poor metabolizers of pantoprazole--a preliminary study. Chirality. 1997;9:17-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Cao H, Wang MW, Sun LX, Ikejima T, Hu ZQ, Zhao WH. Pharmacodynamic comparison of pantoprazole enantiomers: inhibition of acid-related lesions and acid secretion in rats and guinea-pigs. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2005;57:923-927. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Welage LS. Pharmacologic features of proton pump inhibitors and their potential relevance to clinical practice. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2003;32:S25-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |