Published online Aug 14, 2017. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i30.5619

Peer-review started: April 11, 2017

First decision: April 17, 2017

Revised: May 4, 2017

Accepted: June 18, 2017

Article in press: June 19, 2017

Published online: August 14, 2017

To systematically review the syndrome of giant gastric lipomas, report 2 new illustrative cases.

Literature systematically reviewed using PubMed for publications since 1980 with following medical subject heading/keywords: (“giant lipoma”) AND (“gastric”) OR [(“lipoma”) and (“gastric”) and (“bleeding”)]. Two authors independently reviewed literature, and decided by consensus which articles to incorporate. Computerized review of pathology/endoscopy records at William Beaumont Hospitals, Royal Oak and Troy, Michigan, January 2005-December 2015, revealed 2 giant gastric lipomas among 117110 consecutive esophagogastroduodenoscopies (EGDs), which were thoroughly reviewed, including re-review of original endoscopic photographs, radiologic images, and pathologic slides.

Giant gastric lipomas are extremely rare: 32 cases reported since 1980, and 2 diagnosed among 117110 consecutive EGDs. Average patient age = 54.5 ± 17.0 years old (males = 22, females = 10). Maximal lipoma dimension averaged 7.9 cm ± 4.1 cm. Ulcerated mass occurred in 21 patients. Lipoma locations: antrum-17, body-and-antrum-4, antrum-intussuscepting-into-small-intestine-3, body-2, fundus-1, and unspecified-5. Intramural locations included submucosal-22, subserosal-2, and unspecified-8. Presentations included: acute upper gastrointestinal (UGI) bleeding-19, abdominal pain-5, nausea/vomiting-5, and asymptomatic-3. Symptoms among patients with UGI bleeding included: weakness/fatigue-6, abdominal pain-4, nausea/vomiting-4, early-satiety-3, dizziness-2, and other-1. Their hemoglobin on admission averaged 7.5 g/dL ± 2.8 g/dL. Patients with GI bleeding had significantly more frequently ulcers than other patients. EGD was extremely helpful diagnostically (n = 31 patients), based on characteristic endoscopic findings, including yellowish hue, well-demarcated margins, smooth overlying mucosa, and endoscopic cushion, tenting, or naked-fat signs. However, endoscopic mucosal biopsies were mostly non-diagnostic (11 of 12 non-diagnostic). Twenty (95%) of 21 abdominal CTs demonstrated characteristic findings of lipomas, including: well-circumscribed, submucosal, and homogeneous mass with attenuation of fat. Endoscopic-ultrasound showed characteristic findings in 4 (80%) of 5 cases: hyperechoic, well-localized, mass in gastric-wall-layer-3. Transabdominal ultrasound and UGI series were generally less helpful. All 32 patients underwent successful therapy without major complications or mortality, including: laparotomy and full-thickness gastric wall resection of tumor using various surgical reconstructions-26; laparotomy-and-enucleation-2; laparoscopic-transgastric-resection-2; endoscopic-mucosal-resection-1, and other-1. Two new illustrative patients are reported who presented with severe UGI bleeding from giant, ulcerated, gastric lipomas.

This systematic review may help standardize the endoscopic and radiologic evaluation and therapy of patients with this syndrome.

Core tip: Systematic literature review of giant gastric lipomas revealed 32 reported cases since 1980, with 2 new cases reported among 117110 esophagogastroduodenoscopies. Two authors independently reviewed literature, and decided by consensus which articles to incorporate. Average-patient-age = 54.5 ± 17.0 years (males = 68.8%). Mean-maximal-lipoma-diameter = 7.9 cm ± 4.1 cm. Lipoma locations: antrum-17, antrum and other gastric segments-7, other-8. Lipomas were submucosal-92%, subserosal-8%. Presentations included: acute upper gastrointestinal (UGI) bleeding-19, abdominal pain-5, nausea/vomiting-5, asymptomatic-3. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy was extremely helpful diagnostically; findings included: yellowish hue, well-demarcated margins, and smooth overlying mucosa. Endoscopic biopsies were infrequently diagnostic. Twenty of 21 abdominal CTs demonstrated characteristic lipoma findings: well-circumscribed, submucosal, and homogeneous mass with fat attenuation. Endoscopic-ultrasound showed characteristic findings in 80%. All patients underwent successful therapy without major complications/mortality, including: laparotomy-with-full-thickness-gastric-wall-resections-26; and other-6. Two newly reported patients presented with severe UGI bleeding from giant, ulcerated, gastric lipomas. This review may help standardize work-up of these patients.

- Citation: Cappell MS, Stevens CE, Amin M. Systematic review of giant gastric lipomas reported since 1980 and report of two new cases in a review of 117110 esophagogastroduodenoscopies. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23(30): 5619-5633

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v23/i30/5619.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i30.5619

Gastric lipomas are rare, constituting < 3% of benign gastric tumors, and < 1% of all gastric tumors[1], and giant gastric lipomas (≥ 4 cm) are extremely rare, with only 32 cases reported since 1980 (Table 1)[1-33]. Although small gastric lipomas are usually asymptomatic, giant gastric lipomas typically produce major symptoms from GI obstruction, tumor ulcers, or acute upper gastrointestinal (UGI) bleeding, with 19 cases of UGI bleeding reported since 1980 (Table 1). Due to its extreme rarity, all prior studies of giant gastric lipomas have comprised single case reports. This work systematically reviews the literature since 1980, and collates the case reports scattered among various and sometimes obscure journals, to semi-quantitatively describe the clinical presentation, endoscopic and radiologic findings, and therapy of the disease; and to report two new illustrative cases who presented with massive, life-threatening UGI bleeding among 117110 analyzed esophagogastroduodenoscopies (EGDs) at two large hospitals.

| Ref. | Age, sex, clinical presentation, PMH, signs and lab abnormalities | Diagnostic work-up | Treatment, pathology | Outcome and follow-up |

| Upper GI bleeding | ||||

| Current case report 1 | 63 y. o. M with previous medical history of hypertension and hyperlipidemia presented with melena and dyspnea on exertion for 3 d and epigastric pain, early satiety and 10-kg weight loss during the last 6 mo. BP = 144/77 mm/Hg, pulse = 87/min. Hgb = 6.2 g/dL | EGD: 13-cm-wide, submucosal, yellowish, gastric mass in antrum covered by smooth mucosa except for focal ulcerationAbdominal CT: well-circumscribed, uniform 13.4 cm × 8.4 cm × 8.2 cm mass, with attenuation characteristic for fat | Laparotomy: Resected by subtotal gastrectomy extended by partial bulbar duodenectomy with Billroth II reconstructionPathology: Homogeneous, submucosal, soft, 14.5 cm × 8.7 cm × 7.5 cm mass. Lipoma with spindle cell variant by CD34 positivity by immunohistochemistry | Did well postoperatively with no complications. Asymptomatic at 8 wk of follow-up |

| Current case report 2 | 78 y. o. F presented with melena for 3 d, associated with weakness and orthostatic dizziness. BP = 124/67 mmHg, pulse = 68/min. Rectal exam-melena. Hgb = 7.1 g/dL | Abdominal CT: submucosal, 9.5 cm × 6.0 cm × 4.5 cm, antral mass. EGD: large, focally ulcerated, antral gastric mass, exhibiting a positive cushion sign | Laparotomy: large, 9.0 cm × 6.0 cm × 4.5 cm, submucosal mass excised by distal gastrectomy. Pathology: lipoma | Patient discharged 5 d postoperatively with no further bleeding |

| Ramdass et al[1], 2013 | 37 y. o. F with epigastric pain, melena, vomiting and weakness for 4 d. Pallor and epigastric tenderness. Hgb = 5.9 g/dL. Transfused 6 units packed erythrocytes | EGD: submucosal mass with 1 cm central ulcer in gastric body | Gastric body. Laparotomy: 4 cm × 3.5 cm × 3.2 cm mass at junction of body and antrum removed surgicallyPathology: lipoma | Did well postoperatively with uneventful recovery |

| Almohsin et al[2], 2015 | 61 y. o. M presented with hematemesis, melena, epigastric pain, and fatigue | EGD: Gastric mass with an ulcer. Endoscopic biopsies: benign tissue. EUS: large, hyperechoic, antral, submucosal lesion. Abdominal CT: 8.5 cm × 5 cm submucosal, well-encapsulated antral lesion with density of fat with ulcerated overlying mucosa | Laparotomy: enucleation of lesion and overlying mucosa. Pathology: lipoma | Remained well at 9 mo follow-up |

| Beck et al[3] ,1997 | 13 y, o. M with hematemesis, melena and abdominal pain for 2 d. Occasional nausea and vomiting for several years. Benign abdomenHgb = 10.5 g/dL | Abdominal radiograph: polypoid mass. EGD: 8 cm × 3 cm × 4 cm soft and compressible, polypoid mass with basal ulceration on anterolateral wall of antrum. Endoscopic mucosal biopsy: normal antral tissue. Abdominal CT: smooth, uniform intraluminal mass with low attenuation in submucosal layer | Endoscopic polypectomy: Unsuccessful due to thick polyp stalk and patient pain during attempted polypectomySurgery: Excision of polypPathology: lipoma | Uneventful postoperative course. Patient asymptomatic |

| Bijlani et al[4], 1993 | 70 y. o. M presented with acute hematemesis. Physical examination revealed pallor. Hgb = 7.0 g/dL | EGD: Protruding mass in antrum. Could not traverse endoscope beyond mass. Endoscopic biopsies: normalUGI series: space-occupying lesion in antrumAbdominal USD: normal | Laparotomy: soft, yellowish mass in antrum stretching the serosa. Mass enucleated via serosal approachPathology: lipoma | Uneventful post-operative recovery. Asymptomatic at 6 mo of follow-up |

| Bloch et al[5], 1974 | 55 y, o. F with 1 episode of melenaNausea, epigastric fullness, and belching for 7 mo. Physical exam reveals grapefruit-sized epigastric massN.A | Supine abdominal radiograph: Well-demarcated, large epigastric massUGI series: huge, sharply demarcated, mass in distal two-thirds of stomach with 2 cm × 3 cm ulcer at apex of mass | Distal two-thirds of stomach on anterior wall. Laparotomy: huge, grapefruit size submucosal lipoma arising from anterior wall with shallow central ulcerSurgical resection: not documented | N.A |

| Chu et al[6], 1983 | 61 y. o. F with previous medical history of gastric ulcer and hiatal hernia diagnosed 2 yr earlier presented with melena and weakness for several days. Rectal exam: fecal occult blood. Hgb = 6.0 g/dL. Transfused 3 units of packed erythrocytes | UGI series: sliding hiatal hernia, and golf-ball-sized mass protruding from lesser curve in antrum. Mass moved in and out of pylorusEGD: well-circumscribed, submucosal, 5 cm × 3 cm-mass protruding along lesser curve in antrum. Positive cushion sign | Laparotomy: 5 cm × 4 cm × 3 cm mass in pre-pylorus. Underwent resection of mass with adjacent lesser curvature, and pyloroplastyPathology: lipoma | Uneventful postoperative course and asymptomatic at 1 yr |

| Kibria et al[7], 2009 | 44 y. o. F with hematemesis and melena for 1 d. Hgb = 8.6 g/dL | EGD: Soft, broad-based, 5 cm × 3 cm mass on greater curvature of stomach. Two ulcers on mass. Positive cushion sign. Abdominal CT: 4.5 cm × 3.0 cm gastric mass with attenuation of fat projecting into lumen. Doppler-assisted EUS: submucosal mass of mixed echogenicity | Greater curvature of stomachSurgical resection, 4.8 cm × 3.2 cm, mature adipocytes with ulceration and necrosis of overlying mucosa | Uneventful recovery. Unremarkable EGD at 6 mo of follow-up |

| Kumar et al[8], 2015 | 72 y. o. previously healthy M presented with presyncope associated with diaphoresis and pallor. Rectal exam revealed melena. Hgb = 9.9 g/dL | Abdominal CT: 4.3-cm-wide polypoid mass in antrum consistent with gastric lipoma. EGD: large, submucosal mass in gastric antrum with central ulcer with overlying clot. Ulcer injected with dilute epinephrine | Laparotomy: Gastrostomy with wide excision of antral lesion along anterior wall. Pathology: lipoma | Good postoperative recovery and discharged 3 d after surgery |

| López Cano et al[9], 1991 | 76 y. o. M with recent NSAID use, and hypertension presented with acute melena. Hgb = 6.8 g/dL | EGD: posterior wall of antrum 3.5-cm-wide lesion with overlying smooth mucosa. Central ulceration. Endoscopic biopsy: gastritis. Abdominal ultrasound with water-filled stomach: 4-cm-wide, echogenic submucosal mass | Partial gastrectomyPathology: lipoma | No postoperative complications |

| Myint et al[10], 1996 | 54 y. o. F presented with hematemesis and melena for 1 wk. BP = 70/50 mmHg. Benign abdominal exam. Hgb = 4.0 g/dL. | EGD: 4 cm × 3 cm ulcerated submucosal mass in antrumEndoscopic biopsies: nondiagnostic. Abdominal CT: gastric mass with attenuation value of lipoma | Laparotomy: 6 cm × 6 cm mass in posterior wall of gastric antrum with central ulceration. Pathology: lipoma | Patient alive with no evident disease 6 mo after surgery |

| Ortiz de Solórzapo Aurusa et al[11], 1997 | 60 y. o. F. PMH: vitiligo, acute pancreatitis, duodenal ulcer presented with melena, postprandial pain, nausea, vomiting and early satiety. Pallor. Rectal exam: melena. Hgb = 12.8 g/dL | EGD: antral deformity. No active bleeding. Gastric volvulus? Abdominal USD: 5.8 cm × 3.4 cm pedunculated antral mass intussuscepting into duodenum. Abdominal CT: 4 cm × 3 cm × 3-cm-wide, well-defined, submucosal mass | Surgery; Underwent partial gastrectomy for antral mass intussuscepting into duodenum. Pathology: lipoma | Did well for 6 mo of follow-up |

| Paksoy et al[12], 2003 | 71 y. o. M with acute hematemesis and melena. BP = 110/70 mmHg, Pulse = 100/minHematocrit = 27% | EGD: 4 cm-wide mass with superficial ulcer on posterior gastric wall. Endoscopic biopsies: “benign” lesionAbdominal CT: 4 cm lesion of lipid density in inferioposterior wall of stomach | Inferioposterior wall of stomachSurgery: laparoscopic transgastric resection of 4 cm intramural lipomaPathology: intramural lipoma | Discharged 6 d postoperatively without complications |

| Pérez Cabañas et al[13], 1990 | 73 y. o. M presented with melena and hematemesis for 2 d. Recent NSAID use. PMH: hypertension. Physical exam: pallor, rectal exam-melena. Hgb = 8.6 g/dL. Transfused 5 units of packed erythrocytes | EGD: gastric mass on posterior wall and greater curve with superficial overlying ulcer, small hiatal hernia. Abdominal ultrasound: normal stomach. UGI series: large filling defect, from submucosal lesion | Surgery: Wedge resection for 5 cm × 4 cm submucosal massPathology: ulcerated lipoma | Did well after surgery |

| Priyadarshi et al[14], 2015 | 46 y. o. M with melena for 1 yr. Palpable, soft epigastric lump. Mild epigastric tendernessHgb = 5 mg/dL; coagulation parameters and chemistry WNL | EGD: large mass arising from posterior wall antrum with superficial ulceration. Unable to traverse pylorus due to obstruction. Abdominal CT: huge mass with lobulated surface projecting into gastric lumen with density consistent with fat. Tumor extended into pylorus and caused gastric outlet obstruction | Posterior wall of gastric antrumLaparotomy: Billroth I partial gastrectomy; 14 cm × 11 cm × 5 cm sessile broad based submucosal lipoma; path = mature adipocytes | No reported complications |

| Rao et al[15], 2013 | 60 y. o. M presented with melena, fatigue and pallor. Hgb = 7.2 g/dL | EGD: large, smooth, submucosal bulge along lesser curvature of stomach. Contrast enhanced abdominal CT: Well-defined, encapsulated, submucosal mass with attenuation of fat along lesser curvature of stomach | Laparotomy: large submucosal tumor excised via anterior gastrotomyPathology: 15 cm × 12 cm submucosal tumor with a focal ulcer. Microscopy demonstrates submucosal lipoma | Presently asymptomatic |

| Regge et al[16], 1999 | 52 y. o. M presented with hematemesis and melena. Hgb = 5.5 g/dL | EGD: 3.5-cm-wide, round, pale-pink formation on anterior gastric antrum with oozing superficial ulcer. Hemostasis achieved with dilute epinephrine injection. Abdominal USD: 4-cm-wide hyperechoic antral lesion with distinct margins. Abdominal CT with IV contrast: 4-cm-wide, well-circumscribed, antral lesion with density of fat. Abdominal MRI: Confirmed fat-tissue signal in mass by hyperintensity on T1-weighted images and marked signal reduction on sequences performed with fat suppression | Laparotomy: Antrectomy and gastrojejunal anastomosis via a Roux-en-Y loop. Pathology: lipoma | N.A |

| Sadio et al[17], 2010 | 44 y. o. M with medical history of hypertension, obesity, and sleep-apnea, presented with fatigue and intermittent melena for 1 mo. Physical exam revealed pallor. Hgb = 7.8 g/dL | EGD: 4-cm-wide, yellowish, submucosal mass in gastric fundus with central overlying ulceration. EUS: hyperechoic submucosal mass. Abdominal CT: homogeneous, well-circumscribed mass in fundus with density of fat | Surgery: partial gastric resectionPathology: submucosal lipoma | Did well and discharged 10 d postoperatively |

| Singh et al[18], 1987 | 40 y. o. M with melena, pyrexia, chills, and weakness. BP = 100/70 mmHg, pulse = 106/min, temp = 39 °C, abdomen-soft, nontender, no palpable mass. Hgb = 4.0 g/dL | EGD: huge polypoid tumor in gastric body along greater curve. Multiple small superficial ulcers in antrumEGD biopsies: Mildly inflamed, mature adipose tissueUGI series: large gastric tumor | Gastric body along greater curveLaparotomy: smooth mass in gastric body and antrum. Multiple small ulcerations. Underwent subtotal gastrectomy and gastrojejunostomy. Pathology: 18 cm × 10 cm × 10 cm encapsulated lipoma | Discharged 2 wk postoperatively. Asymptomatic for 1 yr. |

| Youssef et al[19], 1999 | 54 y. o. nonalcoholic F presented with melena and dizzinessPhysical exam: stable vital signs, abdominal tenderness without peritoneal signs. Hgb = 9.2 g/dL | EGD: submucosal protrusion with mucosal erosion along greater curvature in body and antrumAbdominal USD: homogeneous, hyperechoic mass in submucosa of posterior gastric wall. Abdominal CT: homogeneous, 5.1 cm × 3.7 cm lesion with density of fat in posterior gastric wall | Laparotomy: with full-thickness resection of lesionPathology: 5.2 cm × 3.8 cm × 3.2 cm submucosal lipoma | Uneventful recovery |

| Abdominal pain | ||||

| Alberti et al[20], 1999 | 11 y. o. F with periumbilical and RLQ abdominal pain for 3 yr. Outpatient UGI series revealed multiple filling defects in gastric antrum and body. Normal physical examination. Abdomen was soft with no palpable mass. No fecal occult bloodNormal routine blood studies. Normal iron studies | EGD: multiple, large, soft, masses protruding into gastric body and antrum with normal overlying mucosa. Gastric biopsies: normal mucosa. Abdominal USD: multiple, homogeneous, well-encapsulated, submucosal masses with attenuation characteristic of fat. Abdominal MRI: solid, hyperintense formations with signal characteristic of fat in gastric body and antrum. Percutaneous transgastric ultrasound guided biopsy: features of lipoma with mild inflammatory infiltrate | Gastric body and antrum. No treatment because became asymptomatic | “Pain progressively relieved”Follow-up MRI of abdomen: no change |

| Hamdane et al[21], 2012 | 51 y. o. M with epigastric painN.A | EGD: soft, large, ulcerated, submucosal mass in antrumEndoscopic biopsies: nonspecific inflammation of gastric mucosa. Abdominal CT: Round, well-circumscribed, low-attenuation, 9-cm-wide, gastric mass | Surgery: total gastrectomy. Pathology: 9 cm × 7.5 cm × 5 cm., mature adipocyte proliferation with variation of cell size in a fibro-myxoid background. Immunohistochemistry: positive to anti-HGMA2, but not S-100, or CD34, No MDM2 or CDK4 amplification, consistent with lipoma | Uneventful recovery. No symptoms at 1 yr follow-up |

| Neto et al[22], 2012 | 63 y. o. M history of dyslipidemia, and hypertension with upper abdominal pain. Physical exam reveals a palpable, moveable upper abdominal massNormal routine laboratory tests | Abdominal USD: large echoic mass compatible with an expansive lesion in gastric antrum. EGD: large bulging mass in posterior gastric wall with three ulcerated areasEndoscopic biopsies: necrotic mucosaAbdominal CT: well-defined, homogeneous, oval mass located within the posterior gastric wall that compressed descending duodenum and had the density of fat | Posterior gastric wall. Laparotomy with a subtotal gastrectomy and D1 lymphade-nectomy with Roux-en-Y reconstruction: 12 cm × 8 cm × 6 cm, lipoma with mature, well differentiated adipocytes surrounded by a fibrous capsule with 3 ulcerative lesions of 0.5 cm, 1 cm, and 1.4 cm | Uneventful recovery with discharge 7 d postoperatively |

| Ramaraj et al[23], 2012 | 52 y. o. M with dyspepsia, anorexia, and early satiety for 6 mo. Gastric ulcer 5 yr earlier. Iron deficiency anemia: Hg = 11.5 g/dL, ferritin = 5 ng/mL | Colonoscopy: within normal limits. EGD: Extrinsic indentation in distal stomach with smooth overlying mucosa. Endoscopic biopsy: normal mucosaCT abdomen: 15 cm × 14 cm fatty tumor in distal stomach | AntrumSubtotal gastrectomy: Submucosal antral lipoma with central ulceration | No postoperative complications. Asymptomatic at 4 wk of follow-up |

| Zak et al[24], 2006 | 58 y. o. M with intermittent upper abdominal discomfort, early satiety, smoking, hyperlipidemia, obesity, PTSD, and depression. Has iron deficiency anemia | EGD: 10 cm × 6 cm smoothly lobulated, submucosal mass in gastric antrum along greater curvature. Chronic inflammation and intestinal metaplasia of gastric mucosa. EUS: hypoechoic submucosal mass surrounded by a hyperechoic layer in posterior wall of stomach, consistent with encapsulated lipoma. Abdominal CT: homogeneous, round, sharply-defined, encapsulated, submucosal lesion with characteristic density of fat | Gastric antrum along the greater curvatureLaparotomy: resection only of the encapsulated massPathology: 10 cm × 6 cm lipoma | Uneventful recovery with discharge on day 7. Follow-up abdominal CT 2 mo later revealed no abnormalities |

| Predominantly nausea and vomiting or obstructive symptoms | ||||

| Aslan et al[25], 2015 | 77 y. o. M with nausea and vomiting,and dyspepsia. Complete blood count and comprehensive metabolic panel: WNL | EGD: submucosal mass with normal overlying mucosa extending into antrum along lesser curve | Endoscopic submucosal resection of 9-cm-long lipoma with an intact capsule | Discharged after 3 d. Resolution of symptoms at 6 mo of follow-up. Repeat endoscopy did not reveal a mass |

| Lin et al[26], 1992 | 77 y. o. F with nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain for 3 wk and 7-kg-weight-loss. Dehydrated and generalized mild abdominal tenderness. Rectal exam: fecal occult blood | UGI series: large polypoid gastric mass intussuscepting into duodenum. Abdominal USD: suspected intussusception. EGD: inadequate examination. Differential of gastric torsion vs intussusception | Laparotomy: large necrotic polypoid intussuscepting mass arising in stomach. Polyp resected at its base. Pathology: large polypoid lipoma | Ultimately recovered and was discharged |

| Mouës et al[27], 2002 | 72 y. o. M with anorexia, early satiety, nausea, and involuntary weight loss. No overt GI bleeding. Left lung lobectomy for bronchial lung cancer 10 yr earlier. Hemoglobin = 4.7 g/dL | EGD: gastric mucosal hypertrophy extending into duodenum. Abdominal USD: hyperechoic mass in small intestine, consistent with lipoma, with likely intussusception. CT abdomen: low attenuation intraluminal tumor compatible with small intestinal lipoma | Laparotomy: large pedunculated tumor intussuscepting into jejunum. Mass reduced back into stomach. Gastrostomy revealed 10 cm × 5 cm superficially ulcerated gastric lipoma. Mass excised. Pathology: mature adipose tissue | Uneventful recovery |

| Nasa et al[28], 2016 | 56 y. o. F with dyspepsia and occasional vomiting for 1 yr. Mild epigastric tenderness | EGD: smooth 5-cm-wide antral bulge with overlying normal mucosa. Positive cushion sign. Endoscopic biopsy: chronic active gastritis from Helicobacter pylori. EUS: homogeneous, hyperechoic, mass arising from layer 3 of gastric wall, compatible with lipoma. Abdominal CT: homogeneous, 6-cm-wide, oval mass in antropyloric region, with density of fat | Antrum and pylorus along lesser curveLaparotomy: Excision of 6 cm wide, encapsulated tumor along lesser curve of stomach | Did well and discharged. Asymptomatic at 6 mo |

| Treska et al[29], 1998 | 61 y. o. M with intermittent vomiting for several days. History of gastric ulcer N.A | UGI series: spherical, smooth, 4.0 cm × 4.5 cm defect in gastric antrum. EGD: protruding, yellowish tumor in prepylorus. Two ulcers above tumor. Abdominal ultrasound: 7 cm × 6 cm × 5 cm echogenic defect in wall of gastric antrum. Abdominal CT: prepyloric intramural lipoma | Gastric antrum. Laparotomy: 7.0 cm × 6.0 cm tumor in prepylorus. Tumor resection of lipoma with performance of Billroth II | Discharge 12 d postoperatively. No GI symptoms 8 mo after surgery |

| Lipoma discovered incidentally in work-up for other condition | ||||

| Al Shammari et al[30], 2016 | 41 y. o. M presented for morbid obesity with a BMI of 43.9 kg/m2 and history of obstructive sleep apnea. Normal routine blood tests | Abdominal ultrasound: liver span of 18.8 cm.EGD: rounded 3 cm × 3 cm mass in antrum with normal overlying mucosa. Positive cushion sign. Abdominal CT: 3.5 cm × 3.0 cm lesion in stomach suspicious for lipoma | Antrum. Laparoscopy: Intragastric submucosal mass excised from inside stomach after gastrostomy. Sleeve gastrectomy then performed for morbid obesity. Pathology: 4 cm × 3 cm × 2 cm lipoma | Discharged 4 d postoperatively. Asymptomatic at 2 wk of follow-up |

| Hyun et al[31], 2002 | 22 y. o. M who underwent abdominal CT as preoperative evaluation of retroperitoneum before orchiectomy for testicular cancer. N.A | Abdominal CT: large gastric mass with attenuation of fat projecting into gastric lumen. EGD: large, soft, sessile mass on greater curve of stomach with overlying pink mucosa. Positive cushion sign. Endoscopic biopsies: normal mucosa. EUS: Submucosal mass with less echogenicity than expected for lipoma | Surgical resection: 12 cm × 9 cm × 2.5 cm mobile mass resected. Pathology: Submucosal gastric lipoma | Doing well at 2 mo follow-up |

| López - Zamudio et al[32], 2015 | 59 y. o. M who underwent abdominal CT performed during episode of acute alcoholic pancreatitis revealed probable pyloroduodenal intussusception of a tumor with attenuation suggestive of fat. Hgb = 9.3 g/dL | EGD: 8 cm long polypoid mass impeding flow near pylorus. EGD biopsy: gastritis and incomplete intestinal metaplasia. Repeat EGD: greater curve posterior wall large pedunculated polyp with central ulcerationRepeat EGD biopsies: chronic gastritis, focal ulceration intestinal metaplasia and Helicobacter pylori infection. EUS: 5.6 cm × 4.9 cm mass in gastric antrum in muscular layer | Surgery: 5 cm × 5 cm tumor in anterior wall of gastric antrum. Underwent antroduodenectomy with gastroduodenal anastomosis and Roux-en-Y | No postoperative surgical complications. Asymptomatic at 18 mo of follow-up |

The literature was systematically reviewed using PubMed for articles published since 1980 with the following medical subject heading (MeSH) or keywords: (“giant lipoma”) AND (gastric) OR [(“lipoma”) and (“gastric”) and (“bleeding”)]; and by reviewing the section on gastrointestinal lipomas in standard pathology textbooks or monographs. Two authors independently reviewed the literature, and decided by consensus which articles to incorporate in this review. After reviewing one case from 1974[5], cases reported before 1980 were selectively excluded because the preoperative evaluation at the time frequently used relatively obsolete tests such as UGI series and often lacked currently mandatory tests such as EGD. Four case reports, written in Spanish[9,11,13,32], were professionally translated into English. Case reports of large gastric adenomas which did not satisfy the minimal size criteria of giant gastric lipomas (≥ 4 cm) were systematically excluded[3,34]. A video publication was excluded because clinical details were not reported[35]. A clinical series of 16 gastric lipomas were excluded because this series lumped together medium-sized and giant lipomas[36].

Computerized review of the pathology records at William Beaumont Hospitals at Royal Oak and at Troy, Michigan from January 2005-December 2015 using the computerized system of PowerPath (Tamtron) and SOFTPath with the software terms (“lipoma” or “lipomas”) AND (“gastric” or “stomach”) revealed 2 cases of giant gastric lipomas. Computerized review of the EGD reports using Provations did not reveal any further cases. These 2 cases were thoroughly reviewed based on medical records, including re-review of the original endoscopic photographs by an expert endoscopist, radiologic images by an expert radiologist, and pathologic slides by an expert pathologist. This dual case report received exemption/approval by the IRB at William Beaumont Hospital, Royal Oak, on October 17, 2016.

Case 1: A 63-year-old, nonalcoholic, man with a medical history of hypertension treated with lisinopril, amlodipine, and nifedipine, and hyperlipidemia treated with lovastatin, presented with epigastric pain, early satiety, and involuntary 10-kg-weight-loss during the last 6 mo, and melena and dyspnea on exertion for 3 d. The vital signs were stable, with a blood pressure of 144/74 mmHg, and pulse of 87/min. The abdomen was soft, nontender, and without hepatosplenomegaly or palpable masses. Rectal examination revealed melena. The hemoglobin was 6.2 g/dL, blood urea nitrogen was 27 mg/dL, and creatinine was 1.40 mg/dL. He had 496000 platelets/mL, a normal international normalized ratio (INR), and normal partial thromboplastin time (PTT). He was transfused two units of packed erythrocytes.

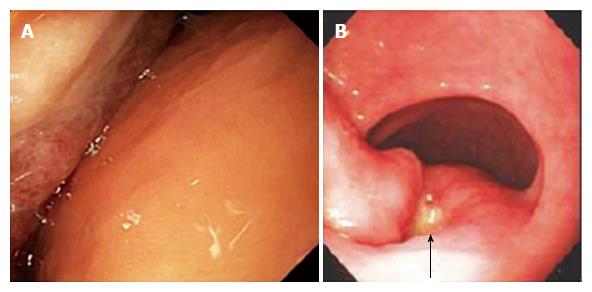

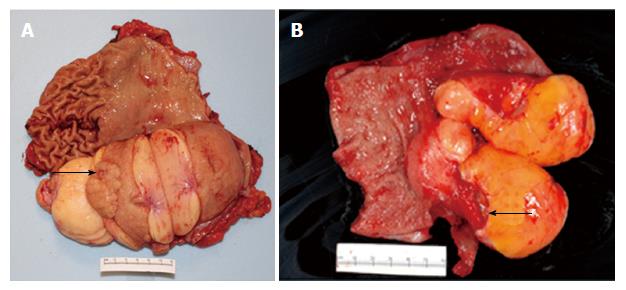

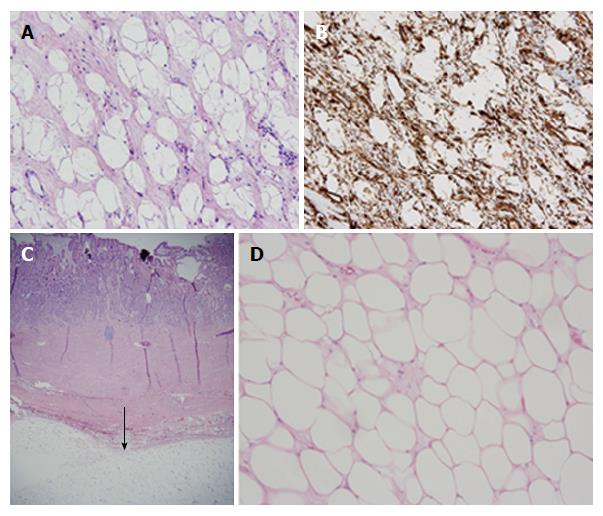

EGD revealed a 13-cm-wide submucosal, yellowish, gastric mass primarily in the antrum, covered by smooth mucosa except for focal ulceration (Figure 1A), and exhibiting the pillow sign, of indentation of the mass with moderate pressure applied via a closed forceps[37,38]. Microscopic examination of multiple mucosal biopsies of the ulcer margin revealed superficial ulceration, granulation tissue, and no malignancy. Abdominal computerized tomography (CT) revealed a well-circumscribed, homogeneous, 13.4 cm × 8.4 cm × 8.2 cm mass, with attenuation characteristic of fat, arising from the gastric antrum and producing a mass effect on the proximal duodenum (Figure 2). A 7-mm-wide lesion in the body of the pancreas was also suspected to be a lipoma based on its characteristic attenuation. The patient underwent laparotomy due to the recent bleeding of the giant lipoma. It was resected via subtotal gastrectomy extended by partial bulbar duodenectomy due to lipoma extension into duodenal bulb, with Billroth II reconstruction. Gross pathology revealed a homogeneous, soft, submucosal mass with a cut surface exposing yellowish, greasy tissue, measuring 14.5 cm × 8.7 cm × 7.5 cm (Figure 3A), which microscopically revealed lipoma (Figure 4A). Immunohistochemical staining revealed positivity for CD34 (Figure 4B), a finding highly consistent with a spindle cell variant lipoma[39]. The patient was discharged 8 d postoperatively, and had no complications during 8 wk of follow-up.

Case 2: A 78-year-old, nonalcoholic, woman with a medical history of atrial fibrillation, peripheral neuropathy, hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes, chronic renal insufficiency, and hysterectomy for uterine fibroids, presented with melena for three days, associated with fatigue and orthostatic dizziness. Medications included warfarin, furosemide, metoprolol, diltiazem, atorvastatin, pioglitazone, amitriptyline, and glimepiride. Physical examination revealed stable vital signs, with a blood pressure of 124/67 mmHg, and pulse of 68/min. There was a heart murmur, and bilateral 3+ lower extremity edema. The abdomen was soft, and non-tender, with normoactive bowel sounds, and no organomegaly. Rectal examination revealed melena. The hemoglobin was 7.1 g/dL, INR was 4.9, platelet count was 306000/mL, and PTT was 42.5 s. The blood urea nitrogen was 44 mg/dL and creatinine was 1.8 mg/dL. An electrocardiogram revealed atrial fibrillation without acute ischemic changes.

She was transfused 2 units of packed erythrocytes and 2 units of fresh frozen plasma. Two-dimensional echocardiography revealed mild mitral valve regurgitation, moderate-to-severe right atrial dilatation, and severe tricuspid valve regurgitation. Abdominal CT revealed a submucosal, antral, gastric mass measuring 9.5 cm × 6.0 cm × 4.5 cm. EGD revealed a large, focally ulcerated, smooth, antral gastric mass, exhibiting the cushion sign (Figure 1B). Microscopic examination of multiple mucosal biopsies of the ulcer margin revealed superficial ulceration, granulation tissue, and no malignancy. The patient underwent surgery due to the recent bleeding of the giant lipoma. At laparotomy, the submucosal mass was excised by distal gastrectomy. Gross pathology of the resected mass revealed a relatively homogeneous, 9.0 cm × 6.0 cm × 4.5 cm, focally ulcerated, mass with a greasy, tan-yellow cut surface (Figure 3B), which microscopically was a lipoma (Figure 4C and D). The patient was discharged 5 d postoperatively with no further GI bleeding[37-39].

Systematic literature review revealed that giant gastric lipomas are rare, with only 32 cases reported since 1980 (Table 1), and only 2 cases currently identified among 117110 EGDs performed during 11 years at William Beaumont Hospital, Royal Oak, one of the five largest hospitals in the United States, and at William Beaumont Hospital, Troy. The 32 reported patients were on average 54.5 ± 17.0 years old. Thirty were adult patients, and two were pediatric patients. Twenty-two were male, and 10 were female. Twenty-one patients had an ulcerated mass. The lipomas averaged 7.9 cm ± 4.1 cm in maximal dimension. Lipoma locations included antrum-17, body and antrum-4, antrum intussuscepting into small intestine-3, gastric body-2, fundus-1, and unspecified-5. This data confirms previous reports that giant gastric lipomas most commonly occur in the antrum[40]. Intramural locations included submucosal-22, subserosal-2, and unspecified-8. This data confirms previous reports that giant gastric lipomas are generally submucosal, but occasionally subserosal[22,36].

Nineteen patients presented with acute UGI bleeding, including melena-11, hematemesis and melena-7, and hematemesis-1. Giant lipomas can ulcerate and bleed secondary to venous stasis[14], friction and trauma of the lipoma tip against the wall contralateral to the lipoma attachment site, or, least likely, from outgrowing their blood supply. Among 19 patients presenting with acute GI bleeding, the hemoglobin on admission averaged 7.5 g/dL ± 2.8 g/dL (unavailable in 2 patients). Symptoms in the 19 patients included: weakness/fatigue-6, abdominal/epigastric pain-4, nausea and vomiting-4, epigastric fullness/early satiety-3, dizziness/presyncope-2, and belching-1. Signs included: pallor-7, epigastric tenderness-3, epigastric mass-3, tachycardia-2, and one each with diaphoresis or hypotension. Among four analyzed variables including age, sex, lipoma size, and lipoma ulceration, only lipoma ulceration was statistically significantly different (more common) in patients presenting with UGI bleeding, than in patients with other presentations (P = 0.004; Table 2). This difference emphasizes the importance of lipoma ulceration in the pathogenesis of bleeding.

| Parameter | mean ± SD of parameter in patients with bleeding | mean ± SD of parameter in patients without bleeding | Patients with bleeding: n with ulcer/total n (% with parameter) | Patients without bleeding: n with parameter/total n (% with parameter) | P value | OR | 95%CI | Statistical test |

| Continuous variables | ||||||||

| Patient age | 54.9 ± 15.5 yr | 53.8 ± 19.6 yr | - | - | 0.87 | NA | NA | Student’s t test |

| Lipoma size | 7.1 cm ± 4.4 cm | 9.3 cm ± 3.1 cm | - | - | 0.16 | NA | NA | Student’s t test |

| Dichotomous variables | ||||||||

| Male sex | - | - | 12/19 (63.2) | 10/13 (76.9) | 0.47 | 0.51 | 0.08-3.17 | χ2 test |

| Ulcer overlying lipoma | - | - | 16/19 (84.2) | 4/13 (30.8) | 0.004 | 12.0 | 1.72-101.9 | Fisher’s exact test |

Five patients presented predominantly with abdominal pain, without acute UGI bleeding, including 2 presenting with iron deficiency anemia. Additional symptoms in these 5 patients included early satiety-2, and anorexia-1. Five patients presented with nausea and vomiting. These patients had additional symptoms including dyspepsia/abdominal pain-3, weight loss-2, anorexia-1, and early satiety-1. Three patients had asymptomatic giant gastric lipomas incidentally detected: by EGD before bariatric surgery for morbid obesity; by abdominal CT in the evaluation of testicular cancer; and by abdominal CT for severe acute pancreatitis.

Thirty-one of the 32 patients underwent EGD (one other patient, see Methods section). EGD is standardly performed preoperatively to characterize the anatomy and show characteristic endoscopic features of lipomas. However, EGD frequently fails to obtain diagnostic tissue due to failure of superficial mucosal biopsies to reach submucosa. Among 12 patients in whom endoscopic biopsy results were reported in the present review, only 1 (8.3%) had lipoma diagnosed pathologically by endoscopic biopsies[18]. Pathologic findings in the other 11 reported biopsy specimens included chronic or nonspecific inflammation, gastritis, and normal or necrotic tissue. Repeated biopsies at the same site (well technique) may increase somewhat the diagnostic yield of endoscopic biopsies. Repeated or deep biopsies at EGD may expose yellow fat from the lipoma, a finding called the “naked fat” sign[41,42]. In the tenting sign observed at EGD the superficial mucosa retracts from the submucosal mass when it is grasped with a forceps because the submucosal lipoma has a fibrous capsule and does not infiltrate into the mucosa. Submucosal lipomas tend to be smooth except for focally ulcerated areas.

CT is currently the standard imaging modality. Lipomas are identified by having an attenuation ranging from -70 to -120 Hounsfield units, characteristic of fat density[20]. Twenty (95.2%) of 21 patients undergoing abdominal CT had CT findings highly suspicious for lipoma, and the other one had diagnostically helpful findings. CT findings consistent with a lipoma include: a well-circumscribed, submucosal, and homogeneous, mass with an attenuation characteristic of fat. Seven patients underwent upper gastrointestinal series which revealed mass size, mass location, and a smooth superficial layer, but did not show characteristic features of lipomas[4-6,13,18,26,29]. All 7 patients undergoing UGI series were reported in publications from 1998 or before, whereas only 4 of 21 patients undergoing CT were reported in publications from 1998 or before (17 CTs reported in publications from 1999-2016) (P < 0.00001, OR > 3.53, Fisher’s exact test). This difference is consistent with replacement of UGI series by EGD and abdominal CT which provide superior characterization. In 9 (82%) of 11 cases abdominal ultrasound showed features suspicious for lipomas of a well-demarcated, submucosal, hyperechoic lesion, but the lesion was missed in 2 cases[4,9,11,16,19,20,22,26,27,29,30]. These results are consistent with abdominal ultrasound being a cheaper, but less definitive test than abdominal CT for giant gastric lipomas.

In 4 (80%) of 5 cases, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) showed characteristic findings of a lipoma of a hyperechoic, well-localized, submucosal mass, but in one case the findings were atypical[17,24,28,31,32]. EUS is useful to identify the primary wall layer of lipomas[22,43]. The currently reported findings are consistent with EUS being an important adjunct test when abdominal CT is non-diagnostic, when a tissue diagnosis is needed preoperatively because of non-diagnostic EGD biopsies, or prior to endoscopic mucosal resection. Both patients undergoing abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) had important findings showing tumor anatomy and exhibiting signals characteristic of fat[16,20].

Therapy was successful in all 32 patients including laparotomy with full-thickness resection of gastric wall containing tumor either via wedge resection, partial gastrectomy, Billroth I resection or other surgery-26; laparotomy with enucleation-2; laparoscopic transgastric resection-2; endoscopic mucosal resection-1, and successful laparotomy with polypectomy after unsuccessful, attempted endoscopic polypectomy-1. No patient suffered major postoperative or postprocedural complications. No patient died from GI bleeding from the lipoma, from the surgery, or from endoscopic therapy.

When GI bleeding or gastric obstruction are associated with a large, ulcerated gastric mass, gastric malignancy may be suspected. It is critical to preoperatively exclude liposarcomas from giant lipomas because liposarcomas require further genetic analysis of pathologic specimens, and chemotherapy after surgical resection[44]. Lipomas have well-demarcated margins on radiologic imaging due to the presence of a fibrous capsule. They are well-differentiated, devoid of lipoblasts, and grow slowly. Liposarcomas have a densitometry close to normal submucosal tissue at abdominal CT[20,45], and are definitively diagnosed by MDM2 and CDK4 gene amplification[21,26]. Other tumors in the differential diagnosis of giant lipomas include GI stromal tumors, such as leiomyoma and fibroma; and rarely intramural tumors, such as neurilemoma, adenomyoma, Brunner’s gland adenoma, and heterotopic pancreas[22].

Treatment for lipomas is not standardized. They are often resected endoscopically when < 4-6 cm, and surgically when > 6 cm[14,22], but endoscopy has been used to resect up to 9-cm-wide gastric lipomas[25]. Lipomas may sometimes be resected by enucleation because they are encapsulated. Resection via subtotal gastrectomy entails much greater morbidity from potential complications of anastomotic leakage, duodenal stump rupture, obstruction, hemorrhage, decreased acid production, delayed gastric emptying, gastroesophageal reflux, and vitamin B12, folate, iron, or calcium deficiencies[24].

The current literature review demonstrates characteristic findings of giant gastric lipomas at EGD, abdominal CT, EUS, and immunohistochemistry, as summarized in Table 3[3,8,14,18,20,22,36-38,40-42,47-52]. The two currently reported cases illustrate characteristic features of giant gastric lipomas: frequently presenting with acute UGI bleeding which is often severe and life-threatening, characteristic endoscopic features, characteristic CT findings, pathologic findings indicating benignity, and excellent post-operative prognosis with rare major morbidity or mortality.

| Test/technique/parameter | Distinctive characteristic | Pathophysiology | Ref. |

| Age | Average age = 54.5 ± 17.0 years old | Current Report | |

| Gender ratio | Male-to-Female ratio approximately 2:1 | Unknown (sexual hormones?) | Current Report |

| Lipoma size | Average maximal dimension = 7.9 cm × 4.1 cm | Current Report | |

| Most common clinical presentation | 19 of 32 presented with acute UGI bleeding | Postulated from ulcer at tip of lipoma caused by rubbing/trauma of tip against gastric wall contralateral to base of lipoma | Current Report |

| EGD | Smooth bulge covered by normal mucosa | Submucosal (or occasionally subserosal) location. No tumor invading mucosa due to benignity | Neto et al[22], 2012, Thompson et al[36], 2003 |

| Most commonly located in gastric antrum | Thompson et al[36], 2003, Menon et al[40], 2014 | ||

| Yellowish hue | Yellow color of adipose tissue in submucosa transmitted to mucosal surface | Menon et al[40], 2014, Chen et al[41], 2014 | |

| Broad base | Rarely pedunculated | Singh et al[18], 1987 | |

| Cushion or pillow sign: easily deforms like a cushion with mild pressure applied against it by an endoscopic probe (closed biopsy forceps). | Lipoma consists of soft, compressible tissue. | De Beer et al[37], 1975, Hwang et al[38], 2005 | |

| Tenting sign: Mucosa easily retracts after it is grasped and gently pulled with a forceps | Mucosa separates from submucosa when gently pulled via forceps because lipoma has fibrous capsule and does not infiltrate into adjacent tissue | Priyadarshi et al[14], 2015 | |

| Naked fat sign: repeated biopsies at same site reveals yellow fatty tissue | Multiple biopsies at same site (using well technique) exposes submucosal lipomatous tissue | Chen et al[41], 2014, Patrick et al[42], 2007 | |

| Moderately frequent focal central ulceration of mucosa | Likely secondary to giant lipoma abutting and rubbing against contralateral gastric wall. Ischemia may also contribute to ulceration. | Kumar, et al[8], 2015, Thompson et al[36], 2003 | |

| Highly useful diagnostic test for lipomas | Typically strongly suggestive of diagnosis | Demonstrates anatomy of mass. Shows if ulcerated or intussuscepting mass. Characteristic findings: yellow hue, smooth overlying mucosa, relatively homogeneous, round margins. Exhibits pillow, tenting or naked fat signs. | Current Report |

| Endoscopic biopsies | Standard endoscopic biopsies usually reveal only normal mucosa and insensitive for pathologic diagnosis. | Standard endoscopic biopsies typically sample superficial mucosa and miss deeper submucosal lipoma. | Current Report, Neto et al[22], 2012 |

| Techniques to increase yield of endoscopic biopsies; use jumbo forceps for endoscopic biopsies; or well technique (repeated endoscopic biopsies at same mucosal site). | Repeated biopsies at same site permits sampling of deeper (submucosal) tissue | Wang et al[47], 2015 | |

| Abdominal CT | Submucosal mass | Typically submucosal, occasionally subserosal, and never mucosal. | Beck et al[3], 1997 |

| Well-circumscribed with well-defined edges | Characteristically has a firm fibrous capsule with no invasion through capsule due to benignity | Thompson et al[36], 2003 | |

| Typically solitary | Multiple gastric lipomas are very rare | Park et al[48], 1999, Skinner, et al[49], 1983 | |

| Homogeneous | Composed of homogeneous lipocytes | Park et al[48], 1999, Alkhatib et al[50], 2012 | |

| Densitometry of -80 to -120 HU (Hounsfield units). | Characteristic of adipose tissue | Alberti et al[20], 1999 | |

| Highly useful as diagnostic test for gastric lipomas | Demonstrates characteristic findings in about 95% of cases. | Characteristic findings: well-circumscribed, submucosal, homogeneous mass with an attenuation characteristic of fat. | Current Report |

| EUS | In third layer of gastric wall | Typically submucosal (rarely subserosal) | Chen et al[43], 2011 |

| Hyperechoic (bright) | Alkhatib et al[50], 2012, Eckardt et al[51], 2012 | ||

| EUS-guided needle biopsy or endoscopic mucosal resection | EUS guidance used to obtain diagnostic deep (submucosal) biopsies | Deep biopsies permit sampling of submucosal lipomas | Alkhatib et al[50], 2012, Karaca et al[52], 2010 |

| Transcutaneous abdominal ultrasound | Not very useful for gastric lipomas. | Supplaned by abdominal CT or EUS for evaluating suspected gastric lipomas | Current Report |

| Upper gastrointestinal series | Mostly obsolete test | CT is a superior alternative | Current Report |

| Histopathology | Diagnostic features | Rounded, plump cells with abundant clear, homogeneous cytoplasm containing fat, eccentric nuclei, mature adipocytes with no lipoblasts, scant stroma, rare inflammatory cells. | Current Report |

| Imunohistochemistry | Reveals no MDM2 or CDK4 gene amplification. | Distinguishes lipoma from liposarcoma. | Shimada et al[45], 2006, Boltze et al[46], 2001 |

| Immunohistochemistry | Lipoma stains positively for CD4 | Indicates spindle-cell lipoma variant | Lau et al[39], 2015 |

The current case reports are limited by retrospective analysis, and by only reporting 2 cases due to disease rarity. The current literature review is likewise limited first, by consisting of single case reports due to syndrome rarity; and second, by retrospectively reporting of case reports. Individually reported cases may be subject to selection bias with preferential reporting of more clinically dramatic or more successful therapeutic interventions. Third, cases from different centers reported somewhat variable clinical data, such as variable follow-up and variable imaging tests (e.g., abdominal CT vs MRI). Fourth, the evaluation of lipomas has evolved over time due to development of better diagnostic tests. This effect was minimized by excluding cases reported before 1980. Fifth, imaging tests were interpreted by various radiologists and pathology specimens were interpreted by various pathologists at various hospitals in the prior case reports.

In conclusion, this systematic literature review provides a comprehensive analysis to help optimize the evaluation and management of suspected giant gastric lipomas. CT and EGD are the standard tests to evaluate suspected giant gastric lipomas. When giant gastric lipomas are identified at abdominal CT by characteristic findings of a homogeneous, well-circumscribed, submucosal mass with characteristic attenuation of fat, EGD with biopsies should be performed, but the endoscopic biopsies may be non-diagnostic. EUS with deep biopsies may be performed to obtain a definitive diagnosis if biopsies from EGD are non-diagnostic. Liposarcoma should be excluded by cytogenetic analysis when necessary. If lipoma is confirmed, endoscopic resection of only the lipoma and its fibrous capsule may be feasible for small-to-moderate sized lesions, with subtotal gastrectomy reserved for especially large lipomas.

Gastric lipomas are rare, constituting < 1% of all gastric tumors, and giant gastric lipomas (≥ 4 cm) are extremely rare, with this systematic review identifying only 32 cases reported since 1980. Although small gastric lipomas are usually asymptomatic, giant gastric lipomas typically produce major, clinically important, symptoms from GI obstruction, tumor ulcers, or upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Due to its extreme rarity, all prior studies of giant gastric lipomas have comprised single case reports. The individual case reports are scattered among numerous, and sometimes obscure, journals. This work systematically reviews the literature since 1980, to comprehensively report what is known about this disease and to inform clinicians and clinical researchers what is not known or controversial about this disease.

A systematic review is important to collate all the prior data presented as case reports to establish what is known about the clinical evaluation (tests) for this disease. This systematic review demonstrates that the standard clinical evaluation should include: (1) abdominopelvic computerized tomography (CT) to demonstrate the characteristic CT findings of a giant gastric lipoma of a well-circumscribed, submucosal, and homogeneous mass with attenuation of fat; and (2) esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) to demonstrate the characteristic endoscopic findings of these lesions of yellowish hue, well-demarcated margins, smooth overlying mucosa, and endoscopic cushion, tenting, or naked fat signs.

This systematic review demonstrates that the following tests are nonstandard or generally obsolete tests: (1) upper gastrointestinal series has been superseded by EGD and should only be performed in highly unusual circumstances; and (2) traditional abdominal ultrasound has been largely superseded by abdominopelvic CT which is a better diagnostic test for this condition, and the traditional abdominal ultrasound should be performed only if the differential diagnosis is broad and not specifically directed at documenting a giant gastric lipoma.

This work systematically reviews several clinically important but controversial topics, including: (1) the role of endoscopic ultrasound: this work shows that conventional mucosal endoscopic biopsies frequently result in a non-diagnostic pathologic diagnosis because giant gastric lipomas are generally submucosal, and therefore endoscopic ultrasound with ultrasound-guided needle biopsies may be necessary if preoperative tissue diagnosis is not obtained by conventional mucosal endoscopic biopsies; and (2) the relative roles of the available therapies: endoscopic mucosal resection, laparoscopic transgastric resection, laparotomy with enucleation, laparotomy with full-thickness wedge resection, and laparotomy with partial gastrectomy and gastric reconstruction.

While several case reports have recently been published on giant gastric lipomas, these case reports generally incorporate limited literature reviews. The present work differs in that it provides a systematic review of the literature. The present work also reports 2 new cases of giant gastric lipomas in a review of 117110 EGDs performed during 11 years at two large teaching hospitals.

This work provides the following highly clinically relevant conclusions: (1) standard evaluation for suspected giant gastric lipomas should include EGD to demonstrate the characteristic endoscopic findings of yellowish hue, well-demarcated margins, smooth overlying mucosa, and endoscopic cushion, tenting, or naked fat signs; (2) at EGD a submucosal mass that is a suspected lipoma should be biopsied, even though the yield of superficial endoscopic biopsies in pathologically diagnosing a gastric lipoma is relatively low. The diagnostic yield of biopsies at EGD may be increased by using jumbo forceps for the biopsies, or by repeated biopsies at the same site (“well” or biopsy-on-biopsy technique); (3) abdominopelvic CT is a standard test in the evaluation of suspected giant gastric lipomas to demonstrate the characteristic CT findings of a giant gastric lipoma of a well-circumscribed, submucosal, and homogeneous mass with characteristic attenuation of fat; (4) upper gastrointestinal (UGI) series is now generally considered an obsolete test for evaluation of suspected giant gastric lipomas and should be replaced by EGD; (5) conventional abdominal ultrasound is not the preferred test for highly suspected giant gastric lipomas, and should be replaced for this indication by abdominopelvic CT. However, abdominal ultrasound may be a very useful initial imaging test for numerous abdominal conditions in which giant gastric lipoma is in the differential diagnosis; and (6) due to scant data about this rare lesion, and absence of prospective, controlled, therapeutic trials there is no universally accepted standardization of preferred therapies for giant gastric lipomas. Reported therapies include endoscopic mucosal resection, laparoscopic transgastric resection, laparotomy with enucleation, laparotomy with full-thickness wedge resection, and laparotomy with partial gastrectomy and gastric reconstruction. All the reported therapies result in a highly favorable prognosis with no reported mortality among the 32 currently reviewed cases and rare severe morbidity because this tumor is benign, is characteristically biologically nonaggressive, and is well-encapsulated that renders it readily amenable to resection. There is recent interest on selecting less invasive techniques for lesion removal, including endoscopic mucosal resection or laparoscopic removal, as opposed to the traditional laparotomy for removal. This systematic review shows that further research is needed on the optimal therapy for giant gastric lipomas, and on individualizing the therapy according to the clinical presentation.

The term giant gastric lipomas refers to gastric lipomas ≥ 4 cm in diameter. The distinction of size ≥ 4 cm vs size < 4 cm is clinically important because gastric lipomas ≥ 4 cm generally produce major clinical symptoms from GI obstruction, tumor ulcers, or upper gastrointestinal bleeding, whereas smaller lesions are usually asymptomatic or produce minor symptoms. Furthermore, lesion size often affects the selected therapeutic modality, with lipomas < 4 cm in diameter often removed endoscopically and lipomas ≥ 4 cm in diameter generally removed surgically.

This is a very important review paper of the main characteristics of the giant gastric lipomas studied in one Hospital through 10 years of study and follow-up. The diagnosis is very well stablished and also the treatment and prognosis.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Mocellin S, Rodrigo L S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Huang Y

| 1. | Ramdass MJ, Mathur S, Seetahal-Maraj P, Barrow S. Gastric lipoma presenting with massive upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2013;2013:506101. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Almohsin M, Meshikhes AW. Gastric lipoma presenting with haematemesis. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015:pii: bcr2014206884. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Beck NS, Lee SK, Lee HJ, Kim HH. Gastric lipoma in a child with bleeding and intermittent vomiting. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1997;24:226-228. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Bijlani RS, Kulkarni VM, Shahani RB, Shah HK, Dalvi A, Samsi AB. Gastric lipoma presenting as obstruction and hematemesis. J Postgrad Med. 1993;39:42-43. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Bloch C, Peck HM. Case report: Giant gastric lipoma. Mt Sinai J Med. 1974;41:593-596. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Chu AG, Clifton JA. Gastric lipoma presenting as peptic ulcer: case report and review of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 1983;78:615-618. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Kibria R, Butt S, Ali SA, Akram S. An unusual case of giant gastric lipoma with hemorrhage. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2009;40:144-145. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kumar P, Gray C. Gastric lipoma: a rare cause of gastrointestinal bleeding. ANZ J Surg. 2015; Epub ahead of print. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | López Cano A, Soria de la Cruz MJ, Rendon Unceta P, Moreno Gallego M, Güezmes Domingo A, Martín Herrera L. [Gastric lipoma diagnosed using transcutaneous echography with a fluid-filled stomach]. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 1991;80:261-263. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Myint M, Atten MJ, Attar BM, Nadimpalli V. Gastric lipoma with severe hemorrhage. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:811-812. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Ortiz de Solórzapo Aurusa FJ, Yarritu Viilanueva C, Ruiz Adrados E, Obelar Bernal L, Acebo García M, Alvarez Rabanal R, Viguri Díaz A. [Gastroduodenal invagination and upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage secondary to gastric lipoma]. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;20:303-305. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Paksoy M, Böler DE, Baca B, Ertürk S, Kapan S, Bavunoglu I, Sirin F. Laparoscopic transgastric resection of a gastric lipoma presenting as acute gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2005;15:163-165. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Pérez Cabañas I, Rodríguez Garrido J, De Miguel Velasco M, Ortiz Hurtado H. [Gastric lipoma: an infrequent cause of upper digestive hemorrhage]. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 1990;78:163-165. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Priyadarshi RN, Anand U, Pandey MK, Chaudhary B, Kumar R. Giant Gastric Lipoma Presenting as Gastric Outlet Obstruction - A Case Report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9:PD03-PD04. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Rao C, Rana SS, Lal A, Kumar M, Behera A, Dahiya D, Joshi K, Bhasin DK. Large gastric lipoma presenting with GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:512-513. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Regge D, Lo Bello G, Martincich L, Bianchi G, Cuomo G, Suriani R, Cavuoto F. A case of bleeding gastric lipoma: US, CT and MR findings. Eur Radiol. 1999;9:256-258. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 22] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sadio A, Peixoto P, Castanheira A, Cancela E, Ministro P, Casimiro C, Silva A. Gastric lipoma--an unusual cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2010;102:398-400. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Singh K, Venkateshwarlu K, Malik AK, Nagi B, Yadav RV. Giant gastric lipoma presenting with fever and melena. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1987;6:181-182. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Youssef PS, Wihelm LH, Schwesinger GO, Howell TD, Petermann J, Zippel RW. Gastric lipoma: A rare cause of gastrointestinal bleeding. Saudi Med J. 1999;20:891-892. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Alberti D, Grazioli L, Orizio P, Matricardi L, Dughi S, Gheza L, Falchetti D, Caccia G. Asymptomatic giant gastric lipoma: What to do? Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:3634-3637. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 31] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hamdane MM, Brahim EB, Salah MB, Haouas N, Bouhafa A, Chedly-Debbiche A. Giant gastric lipoma mimicking well-differentiated liposarcoma. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2012;5:60-63. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Neto FA, Ferreira MC, Bertoncello LC, Neto AA, de Aveiro WC, Bento CA, Cecchino GN, Rocha MA. Gastric lipoma presenting as a giant bulging mass in an oligosymptomatic patient: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6:317. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ramaraj R, Roberts SA, Clarke G, Williams G, Thomas GA. A rare case of iron deficiency. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:82-83. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zak Y, Biagini B, Moore H, Desantis M, Ghosh BC. Submucosal resection of giant gastric lipoma. J Surg Oncol. 2006;94:63-67. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Aslan F, Akpinar Z, Cekic C, Alper E. En bloc resection of a 9 cm giant gastro-duodenal lipoma by endoscopic submucosal dissection. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47:88-89. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lin F, Setya V, Signor W. Gastroduodenal intussusception secondary to a gastric lipoma: a case report and review of the literature. Am Surg. 1992;58:772-774. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Mouës CM, Steenvoorde P, Viersma JH, van Groningen K, de Bruïne JF. Jejunal intussusception of a gastric lipoma: a review of literature. Dig Surg. 2002;19:418-420. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | Nasa M, Choksey A, Phadke A, Sawant P. Gastric lipoma: an unusual cause of dyspeptic symptoms. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;2016. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Treska V, Pesek M, Kreuzberg B, Chudácek Z, Ludvíková M, Topolcan O. Gastric lipoma presenting as upper gastrointestinal obstruction. J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:716-719. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 30. | Al Shammari JO, Al-Shadidi N, Abdulsalam AJ, Al-Daihani AE. Gastric lipoma excision during a laproscopic sleeve gastrecomy: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2016;24:128-130. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Hyun CB, Coyle WJ. Giant gastric lipoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:905. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | López-Zamudio J, Leonher-Ruezga KL, Ramírez-González LR, Razo Jiménez G, González-Ojeda A, Fuentes-Orozco C. [Pedicled gastric lipoma. Case report]. Cir Cir. 2015;83:222-226. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Dargan P, Sodhi P, Jain BK. Bleeding gastric lipoma: case report and review of the literature. Trop Gastroenterol. 2003;24:213-214. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 34. | Johnson DC, DeGennaro VA, Pizzi WF, Nealon TF Jr. Gastric lipomas: a rare cause of massive upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 1981;75:299-301. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 35. | Suarez AL, Dufault DL, Mcvey MC, Shetty A, Elmunzer BJ. Stepwise endoscopic resection of a large gastric lipoma causing gastric outlet obstruction and GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84:180. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Thompson WM, Kende AI, Levy AD. Imaging characteristics of gastric lipomas in 16 adult and pediatric patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:981-985. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 65] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | De Beer RA, Shinya H. Colonic lipomas. An endoscopic analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1975;22:90-91. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 38. | Hwang JH, Saunders MD, Rulyak SJ, Shaw S, Nietsch H, Kimmey MB. A prospective study comparing endoscopy and EUS in the evaluation of GI subepithelial masses. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:202-208. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 39. | Lau SK, Bishop JA, Thompson LD. Spindle cell lipoma of the tongue: a clinicopathologic study of 8 cases and review of the literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2015;9:253-259. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Menon L, Buscaglia JM. Endoscopic approach to subepithelial lesions. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2014;7:123-130. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 53] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Chen Y, Andrews CN. Luminal lipoma: the “pot-of-gold” sign. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:167; discussion 167. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Patrick A, Epstein O. The naked fat sign. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:158; commentary 159. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Chen HT, Xu GQ, Wang LJ, Chen YP, Li YM. Sonographic features of duodenal lipomas in eight clinicopathologically diagnosed patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:2855-2859. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Crago AM, Dickson MA. Liposarcoma: Multimodality Management and Future Targeted Therapies. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2016;25:761-773. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 82] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Shimada S, Ishizawa T, Ishizawa K, Matsumura T, Hasegawa T, Hirose T. The value of MDM2 and CDK4 amplification levels using real-time polymerase chain reaction for the differential diagnosis of liposarcomas and their histologic mimickers. Hum Pathol. 2006;37:1123-1129. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 65] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Boltze C, Schneider-Stock R, Jäger V, Roessner A. Distinction between lipoma and liposarcoma by MDM2 alterations: a case report of simultaneously occurring tumors and review of the literature. Pathol Res Pract. 2001;197:563-568. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Wang H, Tan Y, Zhou Y, Wang Y, Li C, Zhou J, Duan T, Zhang J, Liu D. Submucosal tunneling endoscopic resection for upper gastrointestinal submucosal tumors originating from the muscularis propria layer. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;27:776-780. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 45] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Park SH, Han JK, Kim TK, Lee JW, Kim SH, Kim YI, Choi BI, Yeon KM, Han MC. Unusual gastric tumors: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 1999;19:1435-1446. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 74] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Skinner MS, Broadaway RK, Grossman P, Seckinger D. Multiple gastric lipomas. Dig Dis Sci. 1983;28:1147-1149. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 50. | Alkhatib AA, Faigel DO. Endoscopic ultrasonography-guided diagnosis of subepithelial tumors. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2012;22:187-205, vii. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Eckardt AJ, Jenssen C. Current endoscopic ultrasound-guided approach to incidental subepithelial lesions: optimal or optional? Ann Gastroenterol. 2015;28:160-172. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 52. | Karaca C, Turner BG, Cizginer S, Forcione D, Brugge W. Accuracy of EUS in the evaluation of small gastric subepithelial lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:722-727. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 118] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |