Published online Nov 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i32.12007

Peer-review started: August 3, 2022

First decision: September 5, 2022

Revised: September 18, 2022

Accepted: October 20, 2022

Article in press: October 20, 2022

Published online: November 16, 2022

Processing time: 97 Days and 6.6 Hours

Cases of turbinate mucocele or pyogenic mucocele are extremely rare. During nasal endoscopy, turbinate hypertrophy can be detected in patients with turbinate or pyogenic mucocele. However, in many instances, differentiating between turbinate hypertrophy and turbinate mucocele is difficult. Radiological examinations, such as computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), are essential for the accurate diagnosis of turbinate mucocele. Herein, we report three cases of mucocele or pyogenic mucocele of turbinate, including their clinical presentation, imaging findings, and treatments, to help rhinologists understand this condition better.

Three cases of turbinate and pyogenic mucocele were encountered in our hospital. In all patients, nasal obstruction and headache were the most common symptoms, and physical examination revealed hypertrophic turbinates. On CT scan, mucocele appeared as non-enhancing, homogeneous, hypodense, well-defined, rounded, and expansile lesions. Meanwhile, MRI clearly illustrated the cystic nature of the lesion on T2 sequences. Two patients with inferior turbinate muc

In conclusion, both CT and MRI are helpful in the diagnosis of turbinate or pyo

Core Tip: Herein, we reported three cases of turbinate and pyogenic mucocele, including their clinical presentation, imaging findings, and treatment approach. Concha bullosa was the basis of turbinate and pyogenic mucocele. In our study, nasal obstruction and headaches were the most commonly reported symptoms, which was consistent with previous studies. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are essential for the accurate diagnosis of turbinate mucocele. Surgical removal of turbinate mucocele and pyogenic mucocele is the recommended procedure.

- Citation: Sun SJ, Chen AP, Wan YZ, Ji HZ. Endoscopic nasal surgery for mucocele and pyogenic mucocele of turbinate: Three case reports. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(32): 12007-12014

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i32/12007.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i32.12007

Three stair-like bones protrude from the nasal cavity, namely the inferior, middle, and superior turbinate. The sizes of these turbinates decrease by one-third consecutively; furthermore, the anterior position is successively retracted by one-third[1-3]. With the development of radiologic examinations, including computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), concha bullosa of the middle turbinate has been identified as a relatively common condition[3-7], whereas concha bullosa of the inferior turbinate is considered rare[8-10]. Furthermore, the development of mucocele or pyogenic mucocele from concha bullosa is considered extremely rare. Herein, we report three cases of turbinate mucocele and pyogenic mucocele, including their clinical presentation, imaging, and treatments. This article complies with the “Helsinki Medical Protocol and Ethics Declaration” and has been approved by the Shandong Provincial ENT Hospital Medical Ethics Committee (3701047593066).

Case 1: A 55-year-old female presenting with a chronic headache for more than five years was admitted on October 19, 2016. Over the past six months, the patient had more frequent and severe headaches with bilateral nasal congestion.

Case 2: A 58-year-old male with a 2-year history of bilateral nasal obstruction that was worse on the left side was admitted on December 25, 2019.

Case 3: A 50-year-old male with half a year history of right nasal congestion and a 1-wk history of nasal mass was transferred to our department on April 24, 2020.

Case 1: In the past five years, the patient experienced headaches without an obvious cause. Moreover, the headaches were more pronounced in the morning, mainly in bilateral temporal region, and occurred once a week on average. The patient was treated in the neurology department and underwent a CT scan of the brain, which revealed no obvious abnormalities. During the past six months, the degree and frequency of the patient’s headache had increased significantly (2-3 times a week), requiring oral painkillers for relief; the headache was accompanied by bilateral nasal congestion, especially on the left side. The patient had no runny nose, sneezing, epistaxis, facial pain, or other discomforts.

Case 2: In the past two years, the patient experienced bilateral and intermittent nasal congestion, heavy nasal congestion on the left side at night, frequent mouth breathing at night, and snoring during sleep without an obvious cause. The patient also experienced an occasional headache and mild anosmia on the left side. However, he had no runny nose, sneezing, epistaxis, facial pain, or other discomforts.

Case 3: Since half a year, the patient had right and intermittent nasal congestion with no obvious cause; there was no runny nose, no epistaxis, no headache, and no sleep snoring. Furthermore, he had never been to the department of rhinology. The patient was hospitalized in our hospital due to vertigo 1 wk prior and underwent an MRI of the head. The MRI revealed a mass on the inferior meatus’ right posterior end, so he was transferred to the Department of Rhinology for further treatment.

Case 1: There was no specific past illness.

Case 2: History of right ophthalmoplegia for half a year and right secretory otitis media for two weeks.

Case 3: Meniere’s disease for one week.

All patients have no specific family history of illness.

Case 1: The left inferior turbinate was hypertrophic and proximal to the nasal septum, which was slightly deviated to the right.

Case 2: The left middle turbinate was enlarged, exceeding the lower 1/3rd of the inferior turbinate. Furthermore, the patient’s nasal septum deviated to the left and his right middle ear had fluid effusion.

Case 3: Uplifting in the right posterior end of the inferior meatus and nasal septum deviation to the right.

Case 1-3: All test indicators were in the normal range.

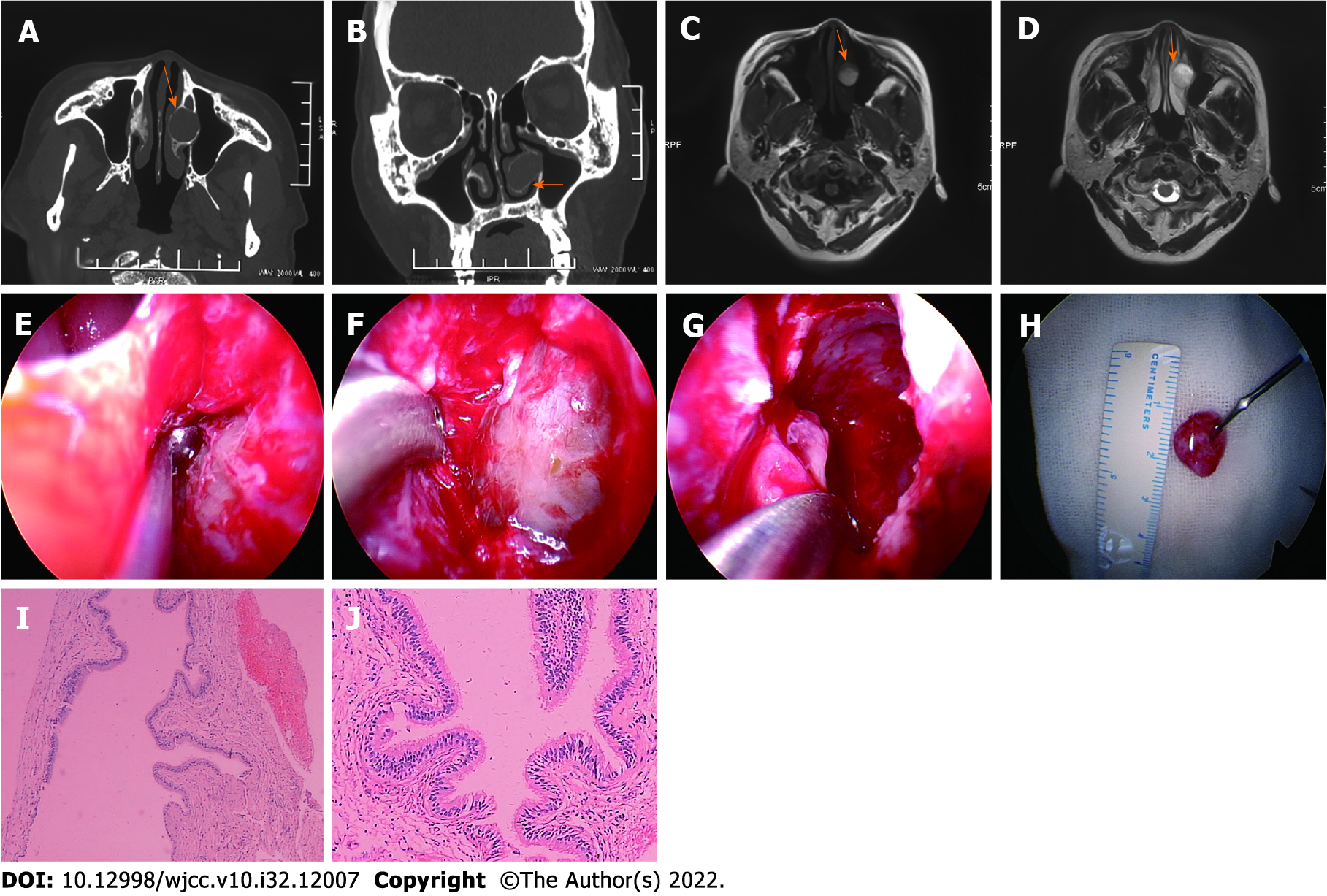

Case 1: CT scan revealed an oval-shaped opaque area with clear edges and thinner cortical bone, which was located in the left inferior turbinate, indicating the presence of a mucocele (Figures 1A and B). Furthermore, T2-weighted MRI images showed a high signal for mucocele fluid, and the edge of the mucocele was clear (Figures 1C and D). In addition, sphenoid sinusitis was observed on both CT and MRI. Sagittal images of CT scans and MRIs were not provided.

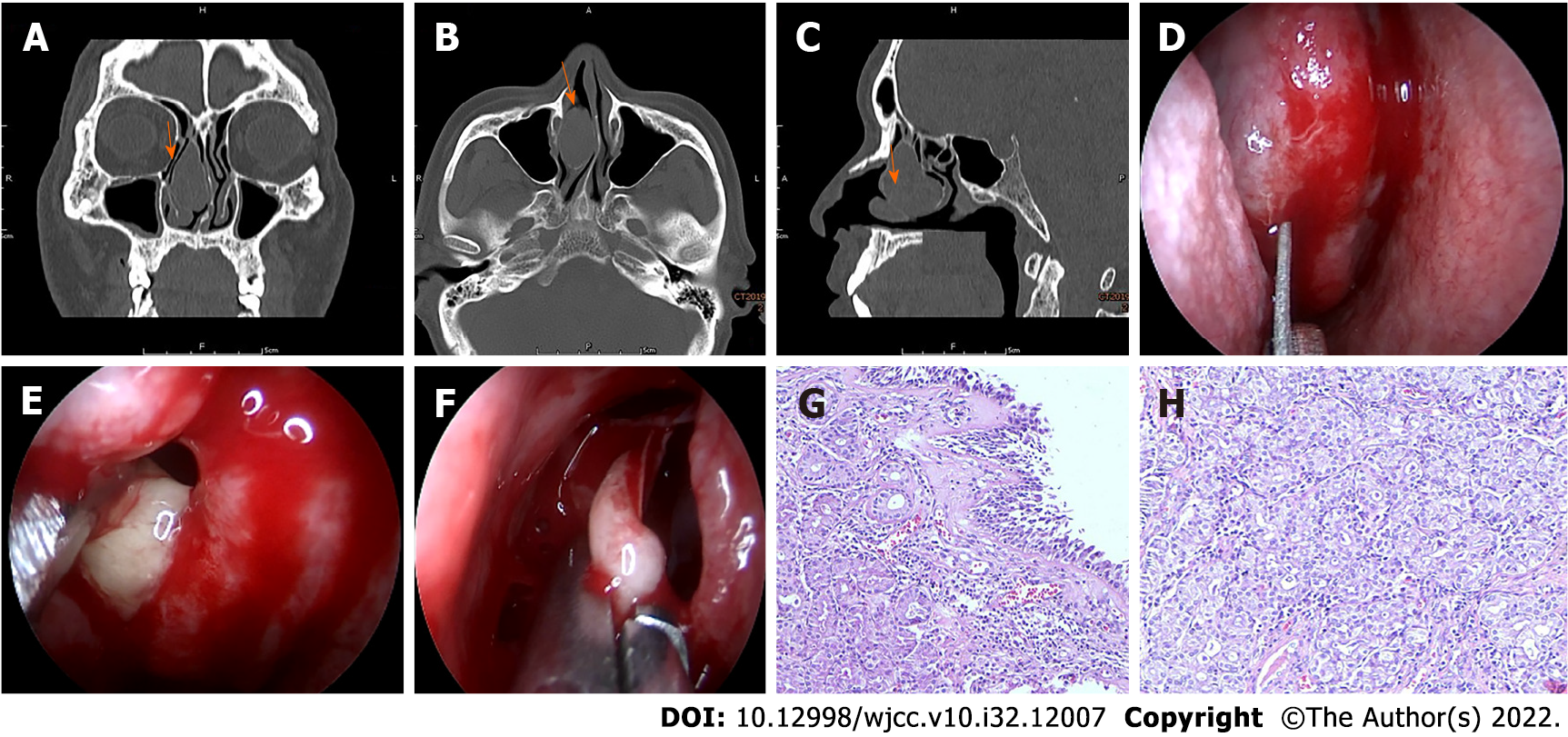

Case 2: CT scan revealed an oval-shaped space-occupying lesion in the left middle turbinate, indicating the presence of a pyogenic mucocele. The pyogenic mucocele showed a homogeneous soft tissue density shadow with clear edges and thinner cortical bone (Figures 2A-C). In addition, right secretory otitis media was also found on the CT scan.

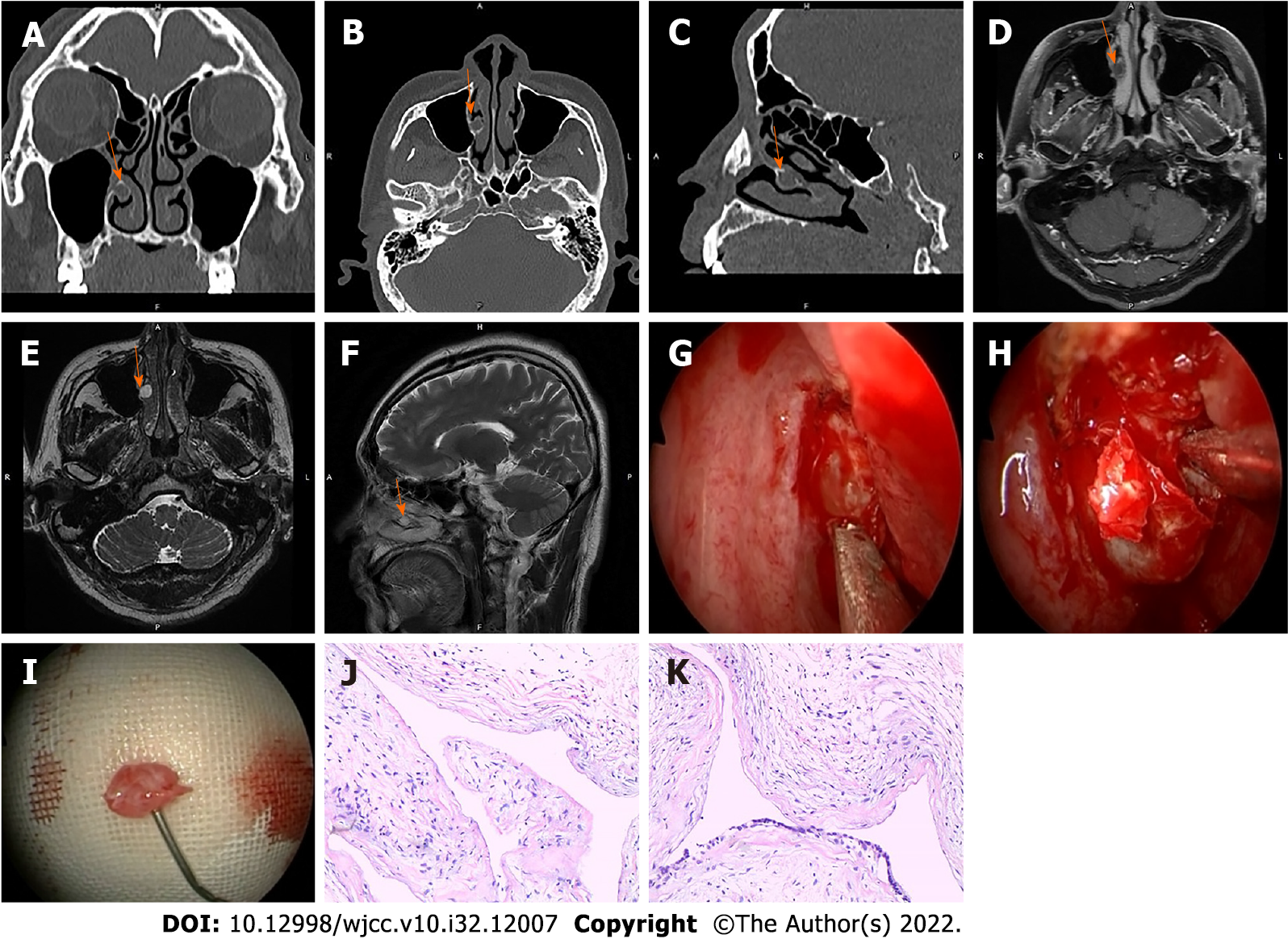

Case 3: CT scan of the sinus revealed a homogeneous soft-tissue density shadow lesion with clear bone edges in the right posterior end of the inferior meatus (Figures 3A-C). MRI revealed clear edges of the mucocele and high homogeneous signals on T2 sequences (Figures 3D-F).

Case 1: The intact lining of the mucocele tissue was stained with hematoxylin and eosin, revealing respiratory epithelium on microscopy (Figures 1I and J).

Case 2: The medial lamellae of the pyogenic mucocele and middle turbinate tissue were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. On microscopy, the pyogenic mucocele lining revealed hyperplasia and hypertrophy with various inflammatory cell infiltrations (Figures 2G and H). Immunohistochemical staining results were as follows: CK-pan(+), CgA(-), SyN(-), P53: 10% of cells were weakly positive (+); and the Ki index was approximately 5%.

Case 3: The intact lining of mucocele tissue was stained with hematoxylin and eosin, revealing respiratory epithelium on microscopy (Figures 3J and K). Immunohistochemical staining results were as follows: CK-pan(+), CK14 (-), P63 (-), SyN(-), and a Ki index was approximately 4%.

Case 1: Mucocele of the inferior turbinate (left); chronic sinusitis.

Case 2: Pyogenic mucocele of the middle turbinate (left); deviation of the nasal septum; secretory otitis (right); ophthalmoplegia (right).

Case 3: Mucocele of the inferior turbinate (right); Meniere’s disease.

Case 1: Following diagnosis, the patient underwent endoscopic surgery under general anesthesia. First, we made a horizontal incision in the inferior turbinate to separate the submucosal tissue until the bone wall of the mucocele. The bone wall was gently peeled off to expose the mucocele lining; the yellow serous fluid was drawn using a syringe, and the mucocele lining was completely removed. Next, we injected normal saline into the dissociative mucocele lining, which showed an inner layer diameter of approximately 1.2 cm (Figures 1E-H). Finally, functional endoscopic sinus surgery on the sphenoid sinus was performed, and the patient recovered with no discomfort.

Case 2: Following diagnosis, the patient underwent endoscopic surgery under general anesthesia. First, a full-thickness longitudinal incision was made at the front end of the right middle turbinate, resulting in white pus oozing out. The medial lamellae of the pyogenic mucocele and the middle turbinate were then resected endoscopically (Figures 2D-F). Finally, in order to treat right ear fullness, the tympanic membrane of the right ear was incised, and a T-shaped tube was inserted. Postoperatively, the patient’s nasal obstruction and ear fullness disappeared completely without discomfort.

Case 3: Following diagnosis, the patient underwent endoscopic surgery under general anesthesia. First, a U-shaped incision was made at the posterior end of the inferior meatus to separate the submucosal tissue from the bone wall of the mucocele. The front and inner bone walls were gently peeled off, yellow serous fluid was drawn using a syringe, and the mucocele lining was completely removed. Next, we injected normal saline into the dissociative mucocele lining, which showed an inner layer diameter of approximately 0.8 cm (Figures 3G-I). Septoplasty under nasal endoscopy was also performed simultaneously. Postoperatively, the patient’s symptoms disappeared completely without discomfort.

Case 1: The patient was followed up on the first, third, sixth month, and 1 year after discharge, and no complaints of headache and nasal congestion were reported during this period.

Case 2: The patient was followed up on the first, third, sixth month, and 1 year after discharge, and no nasal congestion and purulent discharge were observed during this period.

Case 3: The patient was followed up on the first, third, sixth month, and 1 year after discharge, and no nasal congestion was observed during this period.

Mucocele in other body parts present without a lining; however, turbinate mucocele is known to have epithelial linings[11]. Herein, we report two cases of inferior turbinate mucocele and one case of middle turbinate pyogenic mucocele. Concha bullosa, which is an anatomic variant of a turbinate, is responsible for the formation of turbinate mucocele and pyogenic mucocele. Although it is very rare for the inferior turbinate to develop a concha bullosa[8,10], it is a relatively common anatomical variant in the middle turbinate, with an incidence varying from 14%-53.6%[8]. Moreover, concha bullosa is classified into three types, namely lamellar, bulbous, and extensive[12,13]. In this report, we did not find the etiology factors in mucocele development from turbinate bullas.

Previous studies have indicated that either mechanical factors (history of trauma, surgery, nasal polyposis, or benign tumors) or inflammatory factors (infection, allergy, cystic fibrosis) are the main cause of mucocele development[6,14,15]. Mechanical factors induce blockage of a minor salivary gland duct, resulting in the development of a mucocele[6,7,12]. Inflammatory factors may also be the underlying cause of turbinate mucocele, since local lymphocytes may contribute to the release of bone resorption factors[12], and prostaglandin (prostaglandin E2) and proinflammatory cytokines (interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor-α) could provoke osteoclastic bone resorption[16]. In the formation of turbinate mucocele, local bone destruction, remodeling, and expansion occur simultaneously. Mucocele that develops secondary to an infection is referred to as a pyogenic mucocele, which is extremely rare[11,17]. Severe pyogenic mucocele cases may present with intranasal mass, migraine, or orbital involvement[18,19].

Among our patients, nasal obstruction and headaches were the most commonly reported symptoms, which was consistent with previous studies[6,15]. Rhinorrhea is very rarely reported. However, some cases of nasal turbinate mucocele were asymptomatic and diagnosed incidentally on nasal endoscopy and radiologic examinations[5,20]. In our patients, nasal endoscopy could reveal turbinate hypertrophy; however, it needs to be differentiated from turbinate hypertrophy, ethmoidal mucocele, benign or malignant solid tumor (mesenchymal tumor or osseous tumor), meningoencephalocele, and dacryocyst mucocele, based on the patient’s symptoms and physical examination[6,12,14,21-23]. On CT scan, mucocele presents as non-enhancing, homogeneous, hypodense, well-defined, rounded, and expansile lesions[8]. Meanwhile, MRI clearly demonstrates the cystic nature of the lesion on T2 sequences[6,12]. First, the malignant solid tumor was precluded because there was no necrosis, crusting, epistaxis, cervical lymphadenopathy, and bone destruction found by CT and MRI imaging[12]; based on path

In our cases, CT images showed a homogeneous thin bony framework surrounding the turbinate mucocele and thus ruled out ethmoid mucocele and turbinate hypertrophy[22]. According to the CT image, the cyst did not continue with the dacryocyst and dura mater, and the turbinate mucous cyst was surrounded by bone, so meningoencephalocele and dacryocyst mucocele were excluded[28,29]. Therefore, radiological examinations, such as CT or MRI, are essential for the accurate diagnosis of turbinate mucocele[1,3,8,9].

It should be noted that pyogenic mucocele cannot be differentiated from mucocele on CT[6,30], which is important as the infection of a pyogenic mucocele might spread to important surrounding anatomical structures, including the orbit and brain[26]. As such, turbinate mucocele and pyogenic mucocele must always be surgically removed regardless of symptomology[31].

Treatment modalities have changed with the advancement of endoscopic nasal surgery. Although the complete removal of the mucocele lining was recommended in the past, most cases to date involve the marsupialization of lesions, wherein the lesion is reintegrated into the nasal cavity and re-ossification of the bony framework is observed several months after[12]. In our cases, the two patients with inferior turbinate mucocele underwent complete removal, whereas the patient with a pyogenic mucocele underwent marsupialization surgery. Surgical removal of turbinate mucocele and pyogenic mucocele is the recommended procedure, which usually relieves the patient from all symptoms.

In conclusion, turbinate mucocele and pyogenic mucocele from concha bullosa are rare. CT and MRI are both helpful for diagnosis, and endoscopic nasal surgery is the best treatment modality, which has shown good results and no recurrences.

We would like to thank all medical staff who provided data and supported the study.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Abdullah B, Malaysia; Nagar SR, India; Trifan A, Romania S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang JJ

| 1. | Downs BW. The Inferior Turbinate in Rhinoplasty. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2017;25:171-177. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Smith DH, Brook CD, Virani S, Platt MP. The inferior turbinate: An autonomic organ. Am J Otolaryngol. 2018;39:771-775. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Brescia G, Contro G, Frasconi S, Marioni G. Middle turbinate handling during ESS. Our experience. Am J Otolaryngol. 2021;42:102980. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Braun H, Stammberger H. Pneumatization of turbinates. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:668-672. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 52] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Pittore B, Al Safi W, Jarvis SJ. Concha bullosa of the inferior turbinate: an unusual cause of nasal obstruction. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2011;31:47-49. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Khalife S, Marchica C, Zawawi F, Daniel SJ, Manoukian JJ, Tewfik MA. Concha bullosa mucocele: A case series and review of the literature. Allergy Rhinol (Providence). 2016;7:233-243. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Koo SK, Moon JS, Jung SH, Mun MJ. A case of bilateral inferior concha bullosa connecting to maxillary sinus. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;84:526-528. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lee DH, Lim SC. Inferior Turbinate Mucocele. J Craniofac Surg. 2021;32:1638-1640. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lee YW, Kim YM. Mucocoele of the inferior turbinate: a case report. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2016;54:1121-1122. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Al-Sebeih KH, Bu-Abbas MH. Concha bullosa mucocele and mucopyocele: a series of 4 cases. Ear Nose Throat J. 2014;93:28-31. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Toledano A, Herráiz C, Mate A, Plaza G, Aparicio JM, De Los Santos G, Galindo AN. Mucocele of the middle turbinate: a case report. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;126:442-444. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Eloy P, Heylen G, Minavnina J, Ouattassi N. Middle turbinate primary mucocele in a child masquerading as a nasal tumour. B-ENT. 2016;12:159-163. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Bolger WE, Butzin CA, Parsons DS. Paranasal sinus bony anatomic variations and mucosal abnormalities: CT analysis for endoscopic sinus surgery. Laryngoscope. 1991;101:56-64. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 515] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 562] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lee JH, Hong SL, Roh HJ, Cho KS. Concha bullosa mucocele with orbital invasion and secondary frontal sinusitis: a case report. BMC Res Notes. 2013;6:501. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Pinto JA, Cintra PP, de Marqui AC, Perfeito DJ, Ferreira RD, da Silva RH. [Mucopyocele of the middle turbinate: a case report]. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;71:378-381. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lund VJ, Henderson B, Song Y. Involvement of cytokines and vascular adhesion receptors in the pathology of fronto-ethmoidal mucocoeles. Acta Otolaryngol. 1993;113:540-546. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 87] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cinar U, Yiğit O, Uslu B, Alkan S. Pyocele of the middle turbinate: a case report. Kulak Burun Bogaz Ihtis Derg. 2004;12:35-38. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Marianowski R, Farragi M, Zerah M, Brunelle F, Manach Y. Subdural empyema complicating a concha bullosa pyocele. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2002;65:249-252. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yuca K, Kiris M, Kiroglu AF, Bayram I, Cankaya H. A case of concha pyocele (concha bullosa mucocele) mimicking intranasal mass. B-ENT. 2008;4:25-27. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Cankaya H, Egeli E, Kutluhan A, Kiriş M. Pneumatization of the concha inferior as a cause of nasal obstruction. Rhinology. 2001;39:109-111. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Ozcan KM, Selcuk A, Ozcan I, Akdogan O, Dere H. Anatomical variations of nasal turbinates. J Craniofac Surg. 2008;19:1678-1682. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 47] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Okuyucu S, Akoğlu E, Dağli AS. Concha bullosa pyocele. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2008;265:373-375. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Abdel-Aziz M. Mucopyocele of the concha bullosa presenting as a large nasal mass. J Craniofac Surg. 2011;22:1141-1142. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Modlin IM, Kidd M, Falconi M, Filosso PL, Frilling A, Malczewska A, Toumpanakis C, Valk G, Pacak K, Bodei L, Öberg KE. A multigenomic liquid biopsy biomarker for neuroendocrine tumor disease outperforms CgA and has surgical and clinical utility. Ann Oncol. 2021;32:1425-1433. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Yu L, Suye S, Huang R, Liang Q, Fu C. Expression and clinical significance of a new neuroendocrine marker secretagogin in cervical neuroendocrine carcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 2021;74:787-795. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Smirnov A, Lena AM, Cappello A, Panatta E, Anemona L, Bischetti S, Annicchiarico-Petruzzelli M, Mauriello A, Melino G, Candi E. ZNF185 is a p63 target gene critical for epidermal differentiation and squamous cell carcinoma development. Oncogene. 2019;38:1625-1638. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 36] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Huang Z, Pan J, Chen J, Wu S, Wu T, Ye H, Zhang H, Nie X, Huang C. Multicentre clinicopathological study of adenoid cystic carcinoma: A report of 296 cases. Cancer Med. 2021;10:1120-1127. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Kapitanov DN, Shelesko EV, Potapov AA, Kravchuk AD, Zinkevich DN, Nersesyan MV, Satanin LA, Sakharov AV, Danilov GV. [Endoscopic endonasal diagnosis and treatment of skull base meningoencephalocele]. Zh Vopr Neirokhir Im N N Burdenko. 2017;81:38-47. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Pirola F, Spriano G, Ferreli F, Russo E, Di Bari M, Giannitto C, De Virgilio A, Mercante G, Vinciguerra P, Di Maria A, Malvezzi L. Clinical outcome and quality of life of lacrimal sac mucocele treated via endoscopic posterior approach. Am J Otolaryngol. 2022;43:103244. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Göçmen H, Oğuz H, Ceylan K, Samim E. Infected inferior turbinate pneumatization. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;262:979-981. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Fuglsang M, Sørensen LH, Petersen KB, Bille J. 10-year-old with concha bullosa pyogenic mucocele. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |