Published online Jul 6, 2015. doi: 10.5527/wjn.v4.i3.438

Peer-review started: November 13, 2014

First decision: December 26, 2014

Revised: January 14, 2015

Accepted: April 28, 2015

Article in press: April 30, 2015

Published online: July 6, 2015

Processing time: 235 Days and 11.4 Hours

We report a case of a diabetic patient with progressive chronic kidney disease and unexplained hypercalcemia. This unusual presentation and the investigation of all possible causes led us to perform a renal biopsy. The systemic sarcoidosis diagnosis was confirmed by the presence of interstitial multiple granulomas composed of epithelioid and multinucleated giant cells delimited by a thin fibrous reaction, and by pulmonary computed tomography finding of numerous lumps with ground-glass appearance. Sarcoidosis most commonly involves lungs, lymph nodes, skin and eyes, whilst kidney is less frequently involved. When it affects males it is characterized by hypercalcemia, hypercalciuria, and progressive loss of renal function. Early treatment with steroids allows for a gradual improvement in renal function and normalization of calcium serum values. Otherwise, the patient would quickly progress to end stage renal disease. Finding of hypercalcemia in a patient with renal failure must alert physicians because it may be a sign of several pathological entities.

Core tip: This report not only describes a case of kidney sarcoidosis, but also explains the diagnostic algorithm that led to the correct diagnosis of a case wrongly labelled as chronic kidney disease (CKD) secondary to diabetic nephropathy. The absence of other microangiopathic alterations such as retinopathy and secondly the presence of hypercalcemia with hypoparathyroidism in a patient with CKD need to be further explored.

- Citation: Lupica R, Buemi M, Campennì A, Trimboli D, Canale V, Cernaro V, Santoro D. Unexpected hypercalcemia in a diabetic patient with kidney disease. World J Nephrol 2015; 4(3): 438-443

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-6124/full/v4/i3/438.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5527/wjn.v4.i3.438

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease with unknown etiology. The diagnosis requires histological confirmation by the discovery of noncaseating granulomas, the exclusion of other diseases with similar symptoms and the clinical evidence of multiple organ involvement[1]. It is often subclinical or self-limited or the symptoms are shaded[2]. The presentation can be various: respiratory symptoms are not specific and may be mistakenly attributed to other lung diseases, for which empiric therapy may be attempted before other diagnostic tests are performed. Moreover we can find dermatological or ocular abnormalities and totally nonspecific systemic symptoms (fever, weight loss, night sweats). It usually has a benign course with spontaneous resolution in up to two-thirds of cases. However, in one third of cases it is a progressive disorder with significant organ impairment[3].

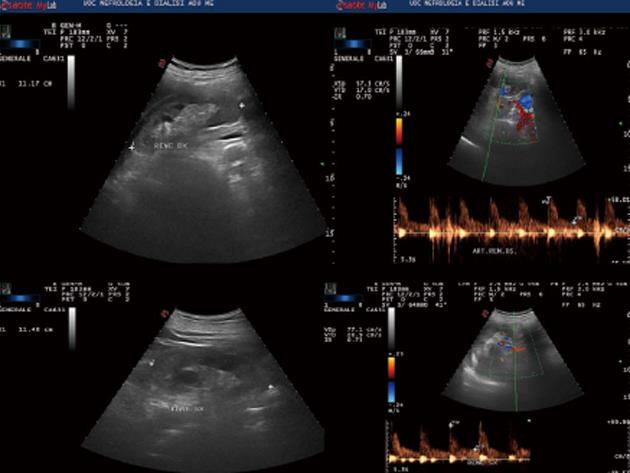

In October 2013, a caucasian 59-year-old man was admitted to Nephrology division. The history was notable for non-insulin diabetes mellitus (ten years), with poor glycemic control (glycosylated haemoglobin A1c = 10.1%). Two months before he had been hospitalized at the internal medicine ward and insulin therapy had been started. Because of increased creatinine levels with lower limb oedema, the patient was referred to the Nephrology Unit. On admission, physical examination revealed normal blood pressure (120/70 mmHg) and heart rate (100 beats/min), moderate leg oedema; laboratory data showed serum creatinine equal to 2.9 mg/dL, calcium 10.4 mg/dL, proteinuria 156 mg/24 h, calculated creatinine clearance (cCrCl) 30.69 mL/min per 1.73 m2 (other blood tests are shown in Table 1); electrocardiogram and echocardiogram were normal. Renal ultrasound (Figure 1) and Colour Doppler showed normal kidneys [antero-posterior diameter of right kidney = 11.17 cm, left kidney = 11.48 cm; normal cortico-medullary representation; resistance index (RI) = 0.70 to right, 0.73 to left]. Fundus oculi was negative for typical lesions of diabetic retinopathy. The patient was discharged with diagnosis of “stage III chronic kidney disease (CKD)” and insulin and antibiotic therapy was recommended. After approximately 1 mo, the patient was hospitalized again due to the worsening of his general conditions and hypercalcemia. He complained of loss of appetite and weakness, with decrease in body weight of about 2 kg. General physical examination was normal except for the presence of right eye hyperaemia, more represented peripheral oedema and reduced breath sounds over the entire pulmonary area. The laboratory tests on the admission are shown in Table 1.

| Serum chemistries | October 2013 | December 2013 | January 2014 | February 2014 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 141 | 136 | 139 | 140 |

| Potassium (mmol/L) | 38 | 4.4 | 4 | 4.6 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 139 | 140 | 117 | 145 |

| HbA1c (%) | 10.1 | 9 | 6.30 | 7 |

| Proteinuria (mg/24 h) | 156 | 408 | 328 | 394 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 2.9 | 3.6 | 1.83 | 1.82 |

| eGFR (mL/min per 1.73 m2) | 30.69 | 20.69 | 42 | 64 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 10.05 | 13.01 | 8.3 | 8.1 |

| Phosphorus (mg/dL) | 4.6 | 4.2 | 3.9 | 4 |

| PTH (pg/mL) | 3.50 | 5.50 | 59.76 | 61.38 |

| VIT D3 (ng/mL) | 30.67 | 21.73 | 20.50 | 19.83 |

| AST (U/L) | 12 | 15 | 17 | 12 |

| ALT (U/L) | 9 | 8 | 24 | 9 |

| ALP (U/L) | 89 | 80 | 79 | 86 |

| Hematologic studies | ||||

| WBC count (x 103/µL) | 10.4 | 13.6 | 11.2 | 10.90 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 10 | 10.6 | 13.60 | 12.2 |

| Platelet count (x 103/µL) | 448 | 456 | 432 |

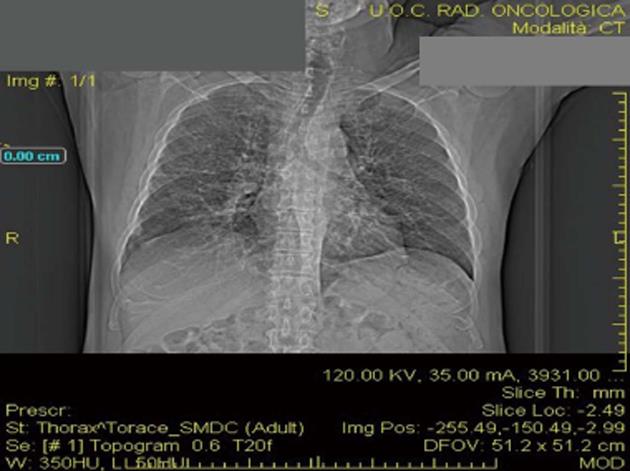

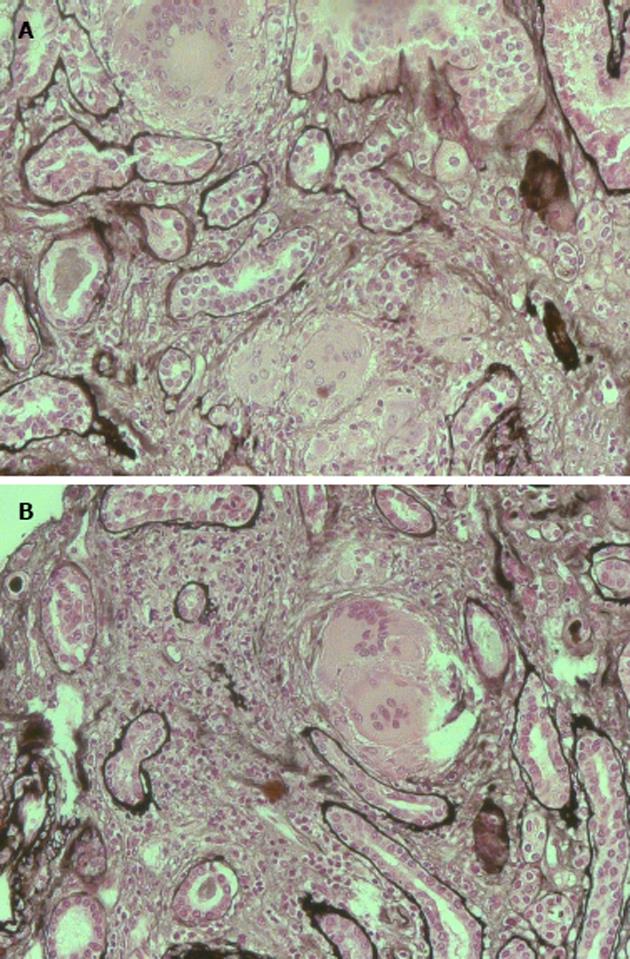

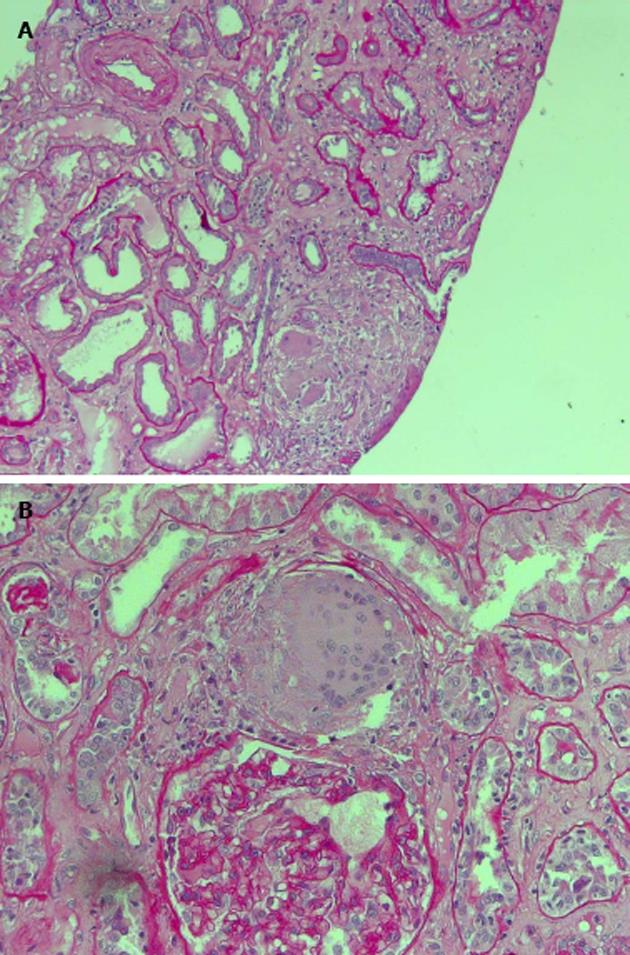

The patient was studied for other secondary causes of hypercalcemia by using an appropriate algorithm[4]. Because of the non-PTH mediated further increase in serum calcium (PTH = 5.5 pg/mL), normal level of 25D (21.73 ng/mL) and absence of vitamin D therapy, hematologic screening was performed to exclude cancer. Chest X-ray (Figure 2) detected a parenchymal consolidation in the right hilum, two pseudo nodular thickenings in the base with a diffuse micronodular pattern. Pulmonary computed tomography (CT) (Figure 3) showed multiple ground-glass like lumps involving both lungs, but not in the basal regions, associated with a thickening of the central and peripheral interstitium and multiple reactive mediastinal lymph nodes. Finally, since data were not suggestive for diabetic nephropathy we decided to perform a renal biopsy. Formalin-fixed and paraffin embedded tissue was processed using standard techniques. Light microscopy showed the presence of interstitial multiple granulomas composed of epithelioid and multinucleated giant cells delimited by a thin fibrous reaction (Figures 4 and 5). Edema was present in the interstitium with mild to moderate lymphocyte-monocyte infiltration and tubular atrophy affecting about 15%-20% of the core. Some tubules showed detachment of necrotic cells in the tubular lumen and in some cases rupture of the basement membrane. Arteriolar hyalinosis and arterial intimal fibrosis were also present. Immunofluorescence staining of frozen sections was negative for IgG, IgM, IgA, C3, C1q, fibrinogen, kappa, and lambda light chains.

Interstitial Granulomatous nephritis secondary to Sarcoidosis. Arteriosclerosis and arteriolosclerosis.

The patient was treated with oral steroids at the dose of 1 mg/kg per day that was progressively tapered.

Normalization in calcium values and improvement of renal function were observed after the first month of corticosteroid therapy (Table 1). There was also resolution of peripheral oedema and asthenia, and improvement of appetite with progressive body weight increase. At the same time, chest CT showed amelioration of pulmonary alterations and disappearance of lumps.

Sarcoidosis most commonly involves lungs, lymph nodes, skin and eyes, whilst kidney is less usually affected[5]. The disease typically occurs in young and middle-aged black race women. Clinical presentation is different depending on the race. Pulmonary involvement covers 90% of patients, of which 61%-63% are women[6]. Among black subjects besides lungs, eyes and skin are often affected. Curiously, calcium metabolism abnormalities are more frequent and more severe in caucasic men with renal interstitial granulomatosis[6] The incidence of renal involvement remains unclear: in autoptic studies, granulomatous infiltrate is found in up to 23% of kidneys, and even up to 48% in small series of biopsies[7]. In our case, the characteristic lesions were related to the presence of multiple granulomas consisting of epithelioid and multinucleated giant cells, delimited by a thin fibrous reaction, interstitial oedema with a mild to moderate lymphocyte and monocyte infiltration and tubular atrophy, involving about 15%-20% of the renal tissue. Our patient was initially classified as a case of CKD secondary to diabetic nephropathy in a context of poor glycemic control. However, first of all the absence of other microangiopathic alterations such as diabetic retinopathy and secondly the presence of hypercalcemia with hypoparathyroidism in a patient with CKD needed to be further explored[8]. On the second admission, the persistence of hypercalcemia despite the suspension of vitamin D therapy, weight loss, anorexia and asthenia suggested for a tubular damage. Differential diagnosis for hypercalcemia at that time was betweeen malignant disease and systemic sarcoidosis. In particular, hypercalcemia characterizes paraneoplastic syndromes[9-12] secondary to bronchial carcinoma, small cell lung cancer, breast, gastric and uterus cancer, myeloma, lymphoma. It could be the first clinical manifestation of a parathyroid adenoma; in an autonomous and independent way, neoplastic tissue produces parathyroid-related hormone (PTHrP), which stimulates bone turnover and calcium reabsorption in the kidney, thus increasing serum calcium values[13]. However, in these situations not only calcium but also PTH is elevated, while in our patient PTH was suppressed. We then considered other causes of hypercalcemia, especially an inappropriate intake or increased activation of vitamin D. In the first hypothesis, suspension of oral vitamin D should have led to a normalization of calcium values, but it was not our case. Moreover, the subject was also suffering from CKD, a condition characterized by reduced production of 1-α-hydroxylase and consequently low concentrations of 1,25 dihydroxycholecalciferol[8] due to progressive replacement of renal parenchyma with fibrotic tissue. We therefore concluded that hypercalcemia was sustained by an abnormal production of 1-α-hydroxylase from granulocyte monocyte-macrophage cells, secondary to a chronic granulomatous disease without any feed-back mechanism of control: this may lead to calcium retention, hypercalciuria and nephrocalcinosis[14]. These situations may be consistent with a diagnosis of sarcoidosis.

Our patient was wrongly categorized as chronic renal failure secondary to diabetes mellitus, whilst it was a case of acute renal injury secondary to sarcoidosis, the identification and treatment of which led to the improvement of renal function. The investigation of all possible causes of “hypercalcemia” allowed to diagnose systemic sarcoidosis confirmed by the evidence of granulomas in renal biopsy. A comprehensive evaluation should be performed in all patients with suspected sarcoidosis, including history, physical examination, chest radiography, pulmonary function tests, peripheral blood counts, complete serum chemistries. Pulmonary evaluation starts with function tests (such as spirometry, diffusing capacity, etc.) reveal a restrictive defect with reduced gas exchange and reduced functional status; chest X-ray. Bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy is the most typical sign at chest radiography. Computed tomography (CT) is essentially face for atypical manifestations of the disease,in order to avoid confusion with differential diagnoses and, sometimes, comorbidities. CT typically shows diffuse pulmonary perilymphatic micronodules, with a perilobular and fissural distribution and upper and posterior predominance, even when an atypical CT pattern is predominant. CT allows deciphering pulmonary lesions in cases of pulmonary fibrosis, pulmonary hypertension, and airflow limitation[15]. Gallium-67-citrate scintigraphy is another imaging method that can be employed both in diagnosis, staging and in the follow-up. Use of fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission/computed tomography (18F-FDG-PET/CT) seems to have higher diagnostic accuracy with respect to Gallium-67-citrate but the high fee of the method limits its employ. Diagnosis relies on compatible clinical and radiological presentation, evidence of noncaseating granulomas and exclusion of other diseases with a similar presentation or histology. However, there are important variations in diagnostic work-up due to diverse expressions of sarcoidosis and differences in clinical practices among physicians. In our case for example, Gallium-67-citrate scintigraphy, 18F-FDG-PET/CT and serum angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) dosage were not made as the result of histological examinations performed on renal tissue was diagnostics. On the other hand, rapid worsening of renal function has been made it necessary to perform biopsy.

In conclusion, we can assume that clinical, laboratory and instrumental data should not be ignored because they are all pieces of a greater puzzle that once rebuilt allows to reach the correct diagnosis and give the right treatment. Like in our case, in a diabetic patient, the presence of hypercalcemia with CKD and the absence of other microangiopathic alterations needs to be further explored because the diagnosis of cancer, paraneoplastic syndrome or parathyroid adenoma has to be excluded as the cause of hypercalcemia.

A caucasian 59-year-old man with non-insulin diabetes mellitus and poor glycemic control, increased serum creatinine level and hypercalcemia.

The patient was initially classified as a case of chronic kidney disease (CKD) secondary to diabetic nephropathy; however, the absence of other microangiopathic alterations in a diabetic patient with CKD needed to be further explored.

Differential diagnosis for hypercalcemia was with cancer, paraneoplastic syndromes and parathyroid adenoma.

Laboratory data showed serum creatinine 2.9 mg/dL, calcium 10.4 mg/dL, proteinuria 156 mg/24 h, cCrCl 30.69 mL/min per 1.73 m2, PTH 5.5 pg/mL, 25D 21.73 ng/mL.

Ultrasound showed normal kidneys. Pulmonary computed tomography revealed multiple ground-glass like lumps involving both lungs.

Histological examination showed the presence of interstitial multiple granulomas composed of epithelioid and multinucleated giant cells delimited by a thin fibrous reaction. Oedema was present in the interstitium with mild to moderate lymphocyte and monocyte infiltration and tubular atrophy affecting about 15%-20% of the core.

The patient was treated with oral steroids at the dose of 1 mg/kg per day that was progressively tapered. Normalization in calcium values and improvement of renal function were observed after the first month of corticosteroid therapy.

Sarcoidosis most commonly involves lungs, lymph nodes, skin and eyes, whilst kidney is less frequently affected. The incidence of renal involvement remains unclear: in autoptic studies, granulomatous infiltrate is found in up to 23% of kidneys, and even up to 48% in small series of biopsies.

The patient was wrongly categorized as chronic renal failure secondary to diabetes mellitus, whilst it was an interesting case of acute kidney injury secondary to sarcoidosis, the identification and treatment of which led to the improvement of renal function.

It is a good article.

P- Reviewer: Prakash J, Turgut A S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Yan JL

| 1. | Hunninghake GW, Costabel U, Ando M, Baughman R, Cordier JF, du Bois R, Eklund A, Kitaichi M, Lynch J, Rizzato G. ATS/ERS/WASOG statement on sarcoidosis. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society/World Association of Sarcoidosis and other Granulomatous Disorders. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 1999;16:149-173. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Newman LS, Rose CS, Maier LA. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1224-1234. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Iannuzzi MC, Fontana JR. Sarcoidosis: clinical presentation, immunopathogenesis, and therapeutics. JAMA. 2011;305:391-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Crowley R, Gittoes N. How to approach hypercalcaemia. Clin Med. 2013;13:287-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mayock RL, Bertrand P, Morrison CE, Scott JH. Manifestations of sarcoidosis. Analysis of 145 patients, with a review of nine series selected from the literature. Am J Med. 1963;35:67-89. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, Judson MA, Rossman MD, Yeager H, Bresnitz EA, DePalo L, Hunninghake G, Iannuzzi MC, Johns CJ. Clinical characteristics of patients in a case control study of sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:1885-1889. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Berliner AR, Haas M, Choi MJ. Sarcoidosis: the nephrologist’s perspective. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;48:856-870. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Levin A, Bakris GL, Molitch M, Smulders M, Tian J, Williams LA, Andress DL. Prevalence of abnormal serum vitamin D, PTH, calcium, and phosphorus in patients with chronic kidney disease: results of the study to evaluate early kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2007;71:31-38. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Nielsen PK, Rasmussen AK, Feldt-Rasmussen U, Brandt M, Christensen L, Olgaard K. Ectopic production of intact parathyroid hormone by a squamous cell lung carcinoma in vivo and in vitro. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:3793-3796. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Nussbaum SR, Gaz RD, Arnold A. Hypercalcemia and ectopic secretion of parathyroid hormone by an ovarian carcinoma with rearrangement of the gene for parathyroid hormone. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1324-1328. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Sargent JT, Smith OP. Haematological emergencies managing hypercalcaemia in adults and children with haematological disorders. Br J Haematol. 2010;149:465-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Stewart AF. Clinical practice. Hypercalcemia associated with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:373-379. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Rosner MH, Dalkin AC. Onco-nephrology: the pathophysiology and treatment of malignancy-associated hypercalcemia. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7:1722-1729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Reichel H, Koeffler HP, Barbers R, Norman AW. Regulation of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 production by cultured alveolar macrophages from normal human donors and from patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1987;65:1201-1209. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Valeyre D, Bernaudin JF, Uzunhan Y, Kambouchner M, Brillet PY, Soussan M, Nunes H. Clinical presentation of sarcoidosis and diagnostic work-up. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;35:336-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |