Published online Jun 22, 2016. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v6.i2.239

Peer-review started: February 27, 2016

First decision: April 15, 2016

Revised: May 4, 2016

Accepted: May 31, 2016

Article in press: June 2, 2016

Published online: June 22, 2016

Processing time: 114 Days and 21.4 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the effectiveness of an intervention for reducing social stigma towards mental illness in adolescents. The effect of gender and knowledge of someone with mental illness was measured.

METHODS: Two hundred and eighty secondary school students were evaluated using the Community Attitudes towards Mental Illness (CAMI) questionnaire. The schools were randomized and some received the intervention and others acted as the control group. The programme consisted of providing information via a documentary film and of contact with healthcare staff in order to reduce the social stigma within the school environment.

RESULTS: The intervention was effective in reducing the CAMI authoritarianism and social restrictiveness subscales. The intervention showed significant changes in girls in terms of authoritarianism and social restrictiveness, while boys only showed significant changes in authoritarianism. Following the intervention, a significant reduction was found in authoritarianism and social restrictiveness in those who knew someone with mental illness, and only in authoritarianism in those who did not know anyone with mental illness.

CONCLUSION: The intervention was effective to reduce social stigma towards people with mental illness, especially in the area of authoritarianism. Some differences were found depending on gender and whether or not the subjects knew someone with mental illness.

Core tip: The intervention was effective to reduce social stigma towards people with mental illness in schools. Authoritarianism was the area that improves more after the intervention. Women and people with knowledge of someone with mental illness were the collective were the intervention was more effective.

- Citation: Vila-Badia R, Martínez-Zambrano F, Arenas O, Casas-Anguera E, García-Morales E, Villellas R, Martín JR, Pérez-Franco MB, Valduciel T, Casellas D, García-Franco M, Miguel J, Balsera J, Pascual G, Julia E, Ochoa S. Effectiveness of an intervention for reducing social stigma towards mental illness in adolescents. World J Psychiatr 2016; 6(2): 239-247

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v6/i2/239.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v6.i2.239

Stigma is a social construct that includes negative attitudes, feelings, beliefs, and behaviours that are configured as prejudice and which has negative consequences for the stigmatized person, making them feel like a lower class[1,2].

People who suffer from mental illness, particularly people with schizophrenia, are one of the most stigmatized groups[3]. Serafini et al[4] (2011) found that the fact that schizophrenia is perceived as a genetic disorder and not environmental disorder, increase the stigma towards this mental illness. Different studies show that this group is subject to prejudice, discrimination, and the greatest impact of stigma leading to social isolation, loss of social roles, lowering of self-esteem, increases the possibility of depression, shame and fear of exclusion[5-9]. Sartorius et al[10] note that stigma is very harmful, and despite the advances and improvements in psychiatry and medicine, stigma continues to grow.

Lack of knowledge and false ideas about mental illness produce an increase in discriminatory behaviour in society towards this group, lower their quality of life, lower rates of help-seeking and service use[11-13]. It is important to try to change society’s attitudes towards people with mental disorders and to reduce stigmatizing behaviours and attitudes. Griffiths et al[14] showed that educational interventions addressed to reducing social stigma were effective. Additionally, different studies describe the best way of reducing social stigma as being through intervention and social integration programmes, specifically, in children and adolescents[15-18]. Negative attitudes toward mental illness are commonly supported by teens[19]. Education is fundamental to improve understanding of mental health, reduce stigma and improve access to care[20]. Therefore, it is a good idea to create intervention programmes in schools, with the objective of counteracting these stereotypes before they arise. In the same line, Roeser[21] and Weist[22] said that in the schools should carry out programs to promote mental health. He explained that it is necessary include training on interdisciplinary collaboration, working closely with schools and community personal health, and on understanding systems issues (for example, community mental health). The study by Pinfold et al[23] revealed that young people do not have a clear idea regarding what mental illness is and the cultural stereotypes associated with it are not fully developed until adolescence or early adulthood and could be modify[18]. So projects aimed at children and adolescents appear to be promising as they allow the modification of ideas relating to mental illness more easily than in adults.

Regarding the type of intervention, it is not clear which elements are most effective. Clement et al[24] showed, with student nurses, that there were no differences in effectiveness between the DVD and direct contact groups. However, greater improvement was produced when both techniques were used together. In the same way, Penn et al[25] found that a film regarding people with schizophrenia could reduce stigmatizing beliefs. The use of filmed material has many advantages. It is more easily extended to the wider population and it has the potential to reach large audiences, it can be made available on the internet, and more cost-effective solution. Also it allows the participation of more presenters, the material is more consistent, there is greater control through editing, and it is less stressful for users compared to live exposure.

Other variables such as gender and knowledge have been studied in relation to the reduction of stigmatizing attitudes. Martínez-Zambrano et al[26] found that women showed significant changes after the intervention in the authoritarianism and social restrictiveness subscales of OMI questionnaire, while men showed changes in negativism and interpersonal etiology. Regarding the question of knowing someone with a mental disorder, those people who knew someone showed significant changes in the authoritarianism, interpersonal etiology, and negativism subscales, while those people who did not know anyone with mental illness improved in restrictiveness and authoritarianism. Högberg et al[9] described how people who are in contact with those who suffer from a mental disorder presented lower levels of social stigma. In the same line, Graves et al[27], in a study of students (aged 17-27 years), considered that those having a higher level of contact with someone with a mental disorder showed lower negative affect towards these people and less social distance, compared to those students with a lower level of contact. Despite this, the high contact group attributed significantly higher levels of dangerousness to the people with a mental disorder; this may be because interactions are more difficult and complex rather than a perception of dangerousness in the strictest sense. On the other hand, Angermeyer et al[28] found that students who were familiar with people with a mental disorder were less likely to believe that people with schizophrenia or major depression were dangerous. Furthermore, another study by Högberg et al[29] revealed that it is not obvious that those individuals with considerable knowledge about mental disorders always have positive attitudes towards persons with a serious mental disorder. So it seems that knowledge of someone with a mental disorder is related to lower levels of social stigma, although some attitudes concerning danger and living in proximity are not clearly defined.

In summary, there are few studies that seek to reduce social stigma in adolescents. Few studies have used filmed material as a tool for intervention to reduce stigma and few of them have been carried out on adolescents. Furthermore, the evaluation of stigma varies widely and does not facilitate the comparability of different studies.

Therefore, the principal aim of the present study was to evaluate the effectiveness of an intervention with professionals and documentary film in the reduction of social stigma towards a mental disorder in adolescents regarding stigma domains (authoritarianism, benevolence, social restrictiveness, and community mental health ideology). Secondary aims were to analyse whether there were differences regarding gender and knowing someone with a mental disorder.

The schools that participated in the study were randomised in two groups. In some schools the assessments and intervention was applied while in the other school only the assessments were provided. The intervention group included n = 128 while the control group included n = 152. The study consisted in measuring the effect of reduction in stigma before and after the intervention, controlling for the effect of intervention. Our sample size of 280 people, would allow to detect an effect size of at least 0.3 between the groups, with a significance level of 5% and 80% power, with an unilateral Student’s t test.

The subjects evaluated were 280 adolescents aged between 14 and 18 years old from four secondary schools located near Barcelona, Spain. Based in a previous study we need a sample of minimum of 100 students in each condition (Martínez-Zambrano et al[26] 2013). Specifically, these four schools, of a middle-class socioeconomic level and roughly the same ethnicity, that participate in the Escola Amiga Program from the Parc Sanitari Sant Joan de Déu (PSSJD). The program offers young people the opportunity to learn firsthand stories of groups at risk of social exclusion and engage to change situations of injustice. The schools that participated in the program are interested in receiving information about several issues and one of this is mental health.

The Community Attitudes towards Mental Illness (CAMI)[30] was chosen for the assessment of social stigma because it is the only scale validated in our context[31]. Originally this questionnaire was devised to predict and explain the reactions of the general population towards local mental health services. The CAMI report social stigma in general population regarding mental disorders. The CAMI is a scale consisting of 40 items with a 5 Likert-scale that ranges from totally agree to totally disagree. Accordingly, to test the Spanish validity and reliability of the CAMI, it was translated and back-translated by our group. The psychometric properties of the instrument showed adequate data, a Cronbach alpha of 0.867, and a temporal stability measured with a difference of one week varied between 0.324 and 0.775. The validation of CAMI showed four factors originally called authoritarianism, benevolence, social restrictiveness, and community mental health ideology[30]. The authoritarianism scale reflects the view of people with a mental disorder as an inferior class. The benevolence scale represents attitudes that are encouraging of people with mental disorders but which exhibit a paternalistic attitude. The social restrictiveness scale assesses danger to society and suggests that people with a mental disorder should be restricted both during and after hospitalization. And, lastly, the community mental health ideology subscale evaluates attitudes and beliefs related to the integration of people with a mental disorder into the community and into society in general. Higher scores in authoritarianism and social restrictiveness indicate greater stigma, while lower scores in benevolence and community mental health ideology indicate greater stigma.

Data were also collected on the gender of the students, their age, and whether or not they personally knew someone with a mental disorder.

The first contact was to introduce ourselves and collected the informed consents. The informed consents were delivered to the teachers before the study started in order to be signed by their parents and to be brought by the students before the first assessment. The questionnaires were anonymous, but the students were asked to use a pseudonym in order to identify their second questionnaire. A total of 12 students were not assessed in the second evaluation, because they did not assist to the school the second day therefore these cases were lost.

Regarding the intervention group, two activities were carried out. In one, the subjects were shown a documentary film related to mental disorder, featuring adolescent characters, in order to produce a greater level of connection and empathy with the students. The film used for intervention lasts approximately 20 min and it was developed for actors coordinated by professionals of the PSSJD. In the film, three adolescents do a school project about mental disorders. At this point, they discuss the choice of this issue, raising many questions and bringing out stereotypes (for example, if they are dangerous, if they can work, the relationship with others, etiology of the illness...). The film is presented as a conversation with different professionals and users with mental disorders, reaching conclusions, in addition to answering the questions initially posed and responding questions about this social group. Once the film was finished, a brainstorming session of questions with the two specialised mental healthcare staff from the rehabilitation services (psychologists, social workers, and occupational therapists) and from the mental health centres (nurse and social workers) was held.

All participants responded to the CAMI questionnaire at two different time points. In the intervention group, the intervention was carried out one week after completing the first questionnaire, and in the week following the intervention the questionnaire was administered for a second time. In the control group, two assessments were performed in a week.

The study was approved by the PSSJD Research and Ethical Committee.

The data analysis was carried out using the statistics package SPSS version 19. The score difference of each factor at the two administration times was calculated in order to analyze the difference between the responses of the students at the two points. The difference in scores for each group was analysed with a Student t test for independent samples. The same test was repeated to assess these differences in terms of gender and whether or not the students knew someone with a mental disorder. Once all the variables were obtained, a general linear model for repeated measures was carried out controlling for the variables of gender and whether or not the subjects knew someone with a mental disorder.

Differences between the means in the two groups, both at baseline and post-intervention were shown in Table 1. The differences of each intervention group were significant in the authoritarianism and social restrictiveness subscales (P < 0.001 and P = 0.019, respectively). Conversely, the benevolence and community mental health ideology subscales did not show significant changes.

| Baseline | Post-intervention | Difference between baseline and post-intervention | T-students | P value | ||||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||

| Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | |||

| Authoritarianism | 26.61 (3.23) | 27.26 (3.75) | 26.79 (3.98) | 25.32 (4.09) | -0.30 (2.83) | 1.94 (4.03) | 5.186 | 0.000 |

| Benevolence | 21.74 (4.00) | 21.98 (4.08) | 22.14 (4.28) | 22.14 (4.13) | -0.27 (2.91) | -0.14 (3.55) | 0.330 | 0.742 |

| Social restrictiveness | 20.89 (4.51) | 20.07 (4.10) | 22.14 (5.16) | 20.34 (4.33) | -1.25 (3.79) | -0.20 (3.49) | 2.355 | 0.019 |

| Community mental health ideology | 24.43 (5.20) | 23.00 (5.22) | 24.79 (5.60) | 22.53 (5.52) | -0.37 (3.55) | 0.40 (4.40) | 1.572 | 0.117 |

Regarding gender, at baseline girls showed scores significantly lower in all of the CAMI subscales: authoritarianism (P < 0.001), benevolence (P = 0.002), social restrictiveness (P = 0.019), and community mental health ideology (P = 0.013) (Table 2). Regarding whether or not they personally knew someone with a mental disorder at baseline, people who did had significantly lower scores on authoritarianism (P = 0.005) and social restrictiveness (P < 0.001) at baseline than those who did not (Table 3).

| Baseline | T-students | P value | ||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||

| Girls | Boys | |||

| Authoritarianism | 25.96 (3.26) | 27.92 (3.45) | 4.824 | 0.000 |

| Benevolence | 21.11 (3.45) | 22.62 (4.46) | 3.121 | 0.002 |

| Social restrictiveness | 19.91 (4.11) | 21.14 (4.50) | 2.352 | 0.019 |

| Community mental health ideology | 22.97 (4.72) | 24.56 (5.65) | 2.504 | 0.013 |

| Baseline | T-students | P value | ||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |||

| Knows someone | Does not know anyone | |||

| Authoritarianism | 26.48 (3.33) | 27.74 (3.66) | -2.847 | 0.005 |

| Benevolence | 21.53 (4.06) | 22.50 (3.91) | -1.887 | 0.060 |

| Social restrictiveness | 19.86 (4.21) | 21.81 (4.32) | -3.594 | 0.000 |

| Community mental health ideology | 23.37 (5.27) | 24.60 (5.14) | -1.811 | 0.071 |

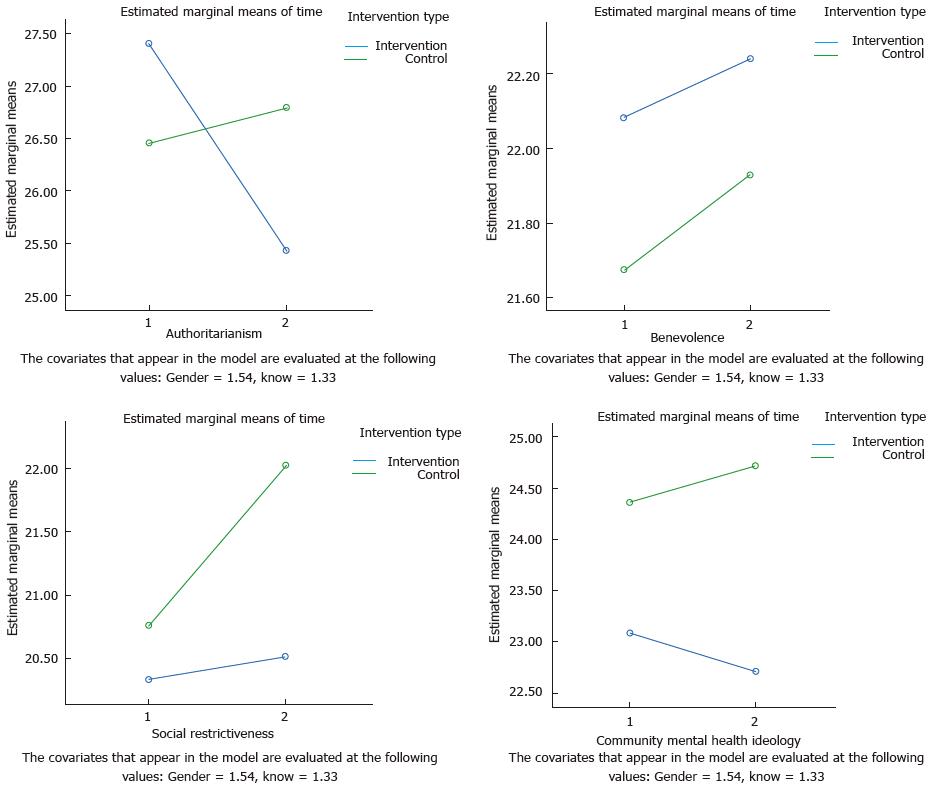

Tables 4 and 5 show the means of each subscale, according to the group at baseline and post-intervention, taking into account the covariates of gender and whether or not the subjects knew someone with a mental disorder, respectively. Significant differences in the authoritarianism subscale were found in the case of boys (P < 0.001), and in authoritarianism and social restrictiveness in the case of the girls (P = 0.010 and P = 0.037, respectively) (Table 5). Lastly, in Table 5, a significant difference in the authoritarianism and social restrictiveness subscales in those people who knew someone with a mental disorder was found (P < 0.001 and P = 0.018, respectively), and only a change in authoritarianism (P = 0.010) in those people who did not know anyone with a mental disorder was significant.

| Baseline | Post-intervention | Difference between baseline and post-intervention | T-students | P value | |||||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||||

| Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | ||||

| Boys | Authoritarianism | 27.44 (3.12) | 28.50 (3.77) | 28.04 (4.31) | 26.18 (4.16) | -0.74 (3.12) | 2.27 (3.93) | 4.771 | 0.000 |

| Benevolence | 22.33 (4.40) | 22.95 (4.54) | 22.93 (4.95) | 22.76 (4.51) | -0.34 (3.12) | 0.19 (3.61) | 0.901 | 0.369 | |

| Social restrictiveness | 21.45 (4.61) | 20.77 (4.39) | 23.06 (5.78) | 21.65 (4.34) | -1.64 (4.06) | -0.63 (3.97) | 1.432 | 0.154 | |

| Community mental health ideology | 25.04 (5.82) | 23.98 (5.43) | 25.99 (6.20) | 23.89 (5.57) | -0.87 (3.81) | 0.32 (5.40) | 1.477 | 0.142 | |

| Girls | Authoritarianism | 25.80 (3.14) | 26.14 (3.41) | 25.58 (3.23) | 24.51 (3.92) | 0.12 (2.47) | 1.67 (4.14) | 2.617 | 0.010 |

| Benevolence | 21.19 (3.53) | 21.02 (3.38) | 21.40 (3.41) | 21.51 (3.69) | -0.21 (2.63) | -0.45 (3.52) | -0.473 | 0.637 | |

| Social restrictiveness | 20.35 (4.37) | 19.36 (3.73) | 21.26 (4.36) | 19.08 (3.99) | -0.88 (3.50) | 0.30 (2.91) | 2.106 | 0.037 | |

| Community mental health ideology | 23.82 (4.45) | 21.97 (4.86) | 23.65 (4.74) | 21.17 (5.17) | 0.13 (3.22) | 0.49 (3.23) | 0.649 | 0.518 | |

| Baseline | Post-intervention | Difference between baseline and post-intervention | T-students | P value | |||||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||||

| Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | ||||

| Knows someone | Authoritarianism | 25.97 (3.27) | 26.88 (3.39) | 26.43 (4.06) | 24.98 (4.14) | -0.47 (3.01) | 1.905 (4.01) | 4.511 | 0.000 |

| Benevolence | 21.53 (4.31) | 21.62 (3.92) | 21.89 (4.3) | 21.61 (4.28) | -0.36 (2.98) | 0.01 (3.51) | 0.571 | 0.569 | |

| Social restrictiveness | 20.19 (4.42) | 19.57 (3.96) | 21.81 (5.44) | 19.81 (4.52) | -1.62 (3.92) | -0.24 (3.57) | 2.388 | 0.018 | |

| Community mental health ideology | 24.24 (5.48) | 22.49 (4.9) | 24.5 (5.80) | 22.03 (5.57) | -0.26 (3.35) | 0.46 (4.37) | 1.039 | 0.300 | |

| Does not know anyone | Authoritarianism | 27.35 (3.13) | 28.52 (4.38) | 27.3 (3.80) | 26.61 (4.07) | 0.05 (2.68) | 1.91 (4.24) | 2.679 | 0.010 |

| Benevolence | 22.2 (3.61) | 23.06 (4.36) | 22.48 (4.24) | 23.67 (3.28) | -0.28 (2.99) | -0.61 (3.63) | -0.437 | 0.663 | |

| Social restrictiveness | 21.93 (4.47) | 21.52 (4.03) | 22.83 (4.75) | 21.82 (3.26) | -0.9 (3.7) | -0.30 (3.39) | 0.783 | 0.435 | |

| Community mental health ideology | 24.7 (4.6) | 24.27 (5.82) | 25.32 (5.16) | 24 (5.29) | -0.62 (3.72) | 0.27 (4.81) | 1.114 | 0.268 | |

Regarding the linear regression models, controlling for gender and whether or not the subject knew someone with a mental disorder, the authoritarianism and social restrictiveness subscales presented significant differences during the intervention in both groups (P < 0.001 and P = 0.017, respectively). In the benevolence and community mental health ideology subscales there were no significant differences controlling for these variables. Figure 1 show the results of the linear regression, comparing the scores between the control group and the intervention group, controlling for gender and whether or not they knew someone with a mental disorder. Authoritarianism showed significant improvement in the adolescents in the intervention group compared to those in the control group. In terms of the social restrictiveness scale, changes were only observed in the control group, with some significantly higher scores and therefore more negative attitudes towards social stigma in mental disorder. Regarding the benevolence and community mental health ideology scales, no significant changes were produced.

The results show that the intervention was effective, with significant changes produced in the intervention group for the most stigmatized factors such as authoritarianism and social restrictiveness. Moreover, in women and people who knew someone with a mental illness the intervention was more effective.

This type of intervention carried out with adolescents was effective, coinciding with other studies[15-18,23,32]. In this line, Penn et al[25] found that a film could reduce beliefs about guilt and responsibility; however it is not useful for reducing behaviour intentions. In addition suggest educational strategies probably do not affect all aspects of psychiatric stigma.

The results of our study indicate that using documentary film is useful for reducing social stigma. The use of documentary film provide to the adolescent information and experiences from different professionals and users. Few studies have used this intervention method in adolescents. Our data are consistent with other studies[24,33]. In the study by Pinfold et al[33] an intervention was carried out in adolescents of the same age as in the present study, although the authors used other actions (workshops and didactic experiences), and it is not clear whether the reduction corresponded to the workshops or to the filmed material, or rather occurred at a general level.

Girls showed fewer stigmatizing patterns than boys at baseline. Boys show higher scores in authoritarianism and social restrictiveness subscale, and girls show higher scores in benevolence and community mental health ideology. Regarding the intervention, both the girls and the boys lowered their social stigma scores with respect to authoritarianism. In the case of the girls, there was also a significant reduction in the social restrictiveness subscale. Therefore, in general, girls have fewer stigmatizing attitudes than boys, both at baseline and post-intervention. These results are consistent with those previously found by the group in Martínez-Zambrano et al[26] and with those found by Morrison[32]. In the same way, the study by Savrun et al[34] showed that female university students were less inclined than men to hold prejudices against people with psychiatric disorders.

Furthermore, differences in the perception of stigma taking into account the variable of knowing someone with a mental disorder were also found. Our results show that when the students knew someone with a mental illness they scored significantly lower in authoritarianism and in social restrictiveness, and higher, although not significantly so, in benevolence, compared to those students that did not know anyone with a mental disorder. In this way, the fact of knowing someone with a mental illness engenders fewer stigmatizing attitudes in adolescents. Our results are consistent with the previous study of the group[26] and with others studies[28,32,35]. The intervention was effective in reducing authoritarianism whether or not the subjects personally knew someone who had a mental disorder.

The results show the attitudes or frames of mind that are less stigmatized in adolescents. Future interventions should take into account differences in terms of gender and whether or not the subjects know someone with a mental disorder. It would be a good idea to carry out an intervention in which, in addition to documentary film and contact with healthcare staff, there was also a certain amount of contact with mental healthcare users. In this way, for those people who do not know anyone with a mental illness, the contact produced would probably allow for a further reduction in the social stigma associated with a mental disorder.

The study has some limitations. Firstly, the intervention shows significant changes in the reduction of social stigma in adolescents. However, although differences have been found in the questionnaire it is difficult to assess if the adolescent have changed their attitude regarding mental health in real life. Moreover, for a future study it would be helpful to carry out another evaluation after a longer period of time, around 6 mo, in order to learn whether the change produced by the intervention is stable. Furthermore, the randomisation was done by the schools in order to control the possibility of the students from the class that did not receive the intervention scoring better after conversation with those who had undergone the intervention. However, it would be better to have a sample from the intervention group and a sample from the control group selected from each school in order to control for the possible effect of the educational methodology of the school and its geographical location, among other factors. Another limitation is the doubt as to the nature of the contact the students have with an individual with mental illness, given the opportunity to respond merely yes or no. Perhaps the answer to this question should be to clarify the relationship with this contact. Moreover better assessment between attitude regarding mental health and behavior addressed to people with a mental illness should be included in next studies. Also, in any future study, the documentary film and the contact with professionals could be combined with some kind of contact with people with a mental disorder, in form of discussions, visits, workshops, or games, among other possibilities, in order to increase the effect of the intervention[24,36-38]. Although Schomerus et al[39] found that providing information on a mental health-mental illness could modify attitudes towards people who suffer of a mental disorder. Therefore, by combining two different types of effective interventions, the results of the stigma reduction would be enhanced, although the cost-effectiveness of this would have to be assessed. The concept of “mental disorder” used in the CAMI questionnaire reflects a period of time in which people with serious mental disorder were considered abnormal and were excluded and isolated. Maybe it is not the most appropriate instrument, but it is the only one that is validated in Spanish. Furthermore, mental disorder is a very broad and imprecise concept, due to a great range of psychiatric disorders included in it, such as depression, anxiety, alcoholism, schizophrenia… This concept has in itself now changed, and a mental disorder is not viewed as unnatural or abnormal and the former isolation no longer exists.

To conclude, the study has demonstrated that interventions with adolescents carried out with documentary film and with healthcare professionals are effective in reducing social stigma, especially in authoritarianism and social restrictiveness. Furthermore, interventions carried out in a school environment should take both gender and the fact of knowing, or not, someone with a mental disorder into account, since these are important differential variables.

We would like to thank the schools that participated in the study: Escola Frederic Mistral, Escola Avenç, Escola Garbí and Escola Sant Josep.

The study shows the effectiveness of an intervention to reduce social stigma towards mental illness in the adolescents. This intervention consists in a documentary film about mental illness and a talk with healthcare professionals.

It is important to try to change the attitudes of our society towards people with mental illness, in order to increase their autoestigma and consequently increase their self-esteem and quality of life as well as their families.

There have been few studies addressed in reducing stigma towards mental illness, much less using visual material. Is not clear the role of gender and the fact of know someone with a mental illness or not in reducing the stigma.

This study provides information on the effectiveness of interventions in schools, made with visual and informative material, to reduce stigma towards mental illness. It is important to take into account gender differences and the fact of know someone with a mental illness or not. Adolescents are a good collective to carry out talks to raise awareness of mental illness.

Stigma is a social construct that includes negative attitudes, feelings, beliefs, and behaviours that are configured as prejudice.

This is, in summary, a manuscript aimed to assess the effectiveness of an intervention for reducing social stigma towards mental illness in a sample of 280 secondary school adolescents. The authors also evaluated the effect of gender and knowledge of someone with mental illness. It has been suggested that this type of intervention was effective in reducing the Community Attitudes towards Mental Illness authoritarianism and social restrictiveness subscales. In addition, the intervention demonstrated significant changes of authoritarianism and social restrictiveness in girls whereas, according to the main results, boys reported only changes concerning authoritarianism. In particular, a significant reduction was reported in authoritarianism and social restrictiveness in those who knew someone with mental illness after the intervention.

P- Reviewer: Richter J, Serafini G, Schweiger U S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Autonell J, Ballús-Creus C, Busquets E. Estigma de la esquizofrenia: factores implicados en su producción y métodos de intervención. Aula Médica Psiquiàtrica. 2001;1:53-68. |

| 2. | Barbato A. Consequences of schizophrenia: a public health perspective. 1st ed. New York: Bullletin WAPR 2000; 6-7. |

| 3. | Brohan E, Elgie R, Sartorius N, Thornicroft G. Self-stigma, empowerment and perceived discrimination among people with schizophrenia in 14 European countries: the GAMIAN-Europe study. Schizophr Res. 2010;122:232-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 318] [Cited by in RCA: 323] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Serafini G, Pompili M, Haghighat R, Pucci D, Pastina M, Lester D, Angeletti G, Tatarelli R, Girardi P. Stigmatization of schizophrenia as perceived by nurses, medical doctors, medical students and patients. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2011;18:576-585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Drapalski AL, Lucksted A, Perrin PB, Aakre JM, Brown CH, DeForge BR, Boyd JE. A model of internalized stigma and its effects on people with mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64:264-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Uçok A, Brohan E, Rose D, Sartorius N, Leese M, Yoon CK, Plooy A, Ertekin BA, Milev R, Thornicroft G. Anticipated discrimination among people with schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;125:77-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Warner R. Community attitudes towards mental disorder. Textbook of Community Psychiatry. New York: Oxford University Press 2001; 453-464. |

| 8. | Whitley R. Social defeat or social resistance? Reaction to fear of crime and violence among people with severe mental illness living in urban ‘recovery communities’. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2011;35:519-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Högberg T, Magnusson A, Ewertzon M, Lützén K. Attitudes towards mental illness in Sweden: adaptation and development of the Community Attitudes towards Mental Illness questionnaire. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2008;17:302-310. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sartorius N, Schulze H. Reducing the Stigma of Mentall Illness. A report from a Global Programme of the World Psychiatric Association. New York: Cambridge University Press 2006; . |

| 11. | Evans-Lacko S, Brohan E, Mojtabai R, Thornicroft G. Association between public views of mental illness and self-stigma among individuals with mental illness in 14 European countries. Psychol Med. 2012;42:1741-1752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 255] [Cited by in RCA: 240] [Article Influence: 18.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Rüsch N, Evans-Lacko SE, Henderson C, Flach C, Thornicroft G. Knowledge and attitudes as predictors of intentions to seek help for and disclose a mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62:675-678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Thornicroft G. Stigma and discrimination limit access to mental health care. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2008;17:14-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 324] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Griffiths KM, Carron-Arthur B, Parsons A, Reid R. Effectiveness of programs for reducing the stigma associated with mental disorders. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World Psychiatry. 2014;13:161-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 269] [Cited by in RCA: 258] [Article Influence: 23.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Battaglia J, Coverdale JH, Bushong CP. Evaluation of a Mental Illness Awareness Week program in public schools. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:324-329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Esters IG, Cooker PG, Ittenbach RF. Effects of a unit of instruction in mental health on rural adolescents’ conceptions of mental illness and attitudes about seeking help. Adolescence. 1998;33:469-476. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Pinto-Foltz MD, Logsdon MC, Myers JA. Feasibility, acceptability, and initial efficacy of a knowledge-contact program to reduce mental illness stigma and improve mental health literacy in adolescents. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72:2011-2019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Schulze B, Richter-Werling M, Matschinger H, Angermeyer MC. Crazy? So what! Effects of a school project on students’ attitudes towards people with schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2003;107:142-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Reavley NJ, Jorm AF. Stigmatizing attitudes towards people with mental disorders: findings from an Australian National Survey of Mental Health Literacy and Stigma. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2011;45:1086-1093. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kelly CM, Jorm AF, Wright A. Improving mental health literacy as a strategy to facilitate early intervention for mental disorders. Med J Aust. 2007;187:S26-S30. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Roeser RW. To Cultivate the Positive … Introduction to the Special Issue on Schooling and Mental Health Issues. J Sch Psychol. 2001;39:99-110. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Weist MD. Challenges and opportunities in moving toward a public health approach in school mental health. J Sch Psychol. 2003;41:77-82. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Pinfold V, Stuart H, Thornicroft G, Arboleda-Flórez J. Working with young people: the impact of mental health awareness programmes in schools in the UK and Canada. World Psychiatry. 2005;4 S1:48-52. |

| 24. | Clement S, van Nieuwenhuizen A, Kassam A, Flach C, Lazarus A, de Castro M, McCrone P, Norman I, Thornicroft G. Filmed v. live social contact interventions to reduce stigma: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2012;201:57-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Penn DL, Chamberlin C, Mueser KT. The effects of a documentary film about schizophrenia on psychiatric stigma. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29:383-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Martínez-Zambrano F, García-Morales E, García-Franco M, Miguel J, Villellas R, Pascual G, Arenas O, Ochoa S. Intervention for reducing stigma: Assessing the influence of gender and knowledge. World J Psychiatry. 2013;3:18-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Graves RE, Chandon ST, Cassisi JE. Natural contact and stigma towards schizophrenia in African Americans: is perceived dangerousness a threat or challenge response? Schizophr Res. 2011;130:271-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H, Corrigan PW. Familiarity with mental illness and social distance from people with schizophrenia and major depression: testing a model using data from a representative population survey. Schizophr Res. 2004;69:175-182. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Högberg T, Magnusson A, Lützén K. To be a nurse or a neighbour? A moral concern for psychiatric nurses living next door to individuals with a mental illness. Nurs Ethics. 2005;12:468-478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Taylor SM, Dear MJ. Scaling community attitudes toward the mentally ill. Schizophr Bull. 1981;7:225-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 435] [Cited by in RCA: 415] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Ochoa S, Martínez-Zambrano F, Vila-Badia R, Arenas O, Casas-Anguera E, García-Morales E, Villellas R, Martín JR, Pérez-Franco MB, Valduciel T. Spanish validation of the social stigma scale: Community Attitudes towards Mental Illness. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment. 2015;pii:S1888-9891(15)00047-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Morrison R; Nursing Students Attitudes toward People with Mental Illness: Do they change after instruction and clinical exposure University of South Florida, College of Nursing, 2011. . |

| 33. | Pinfold V, Toulmin H, Thornicroft G, Huxley P, Farmer P, Graham T. Reducing psychiatric stigma and discrimination: evaluation of educational interventions in UK secondary schools. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182:342-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 283] [Cited by in RCA: 237] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Savrun BM, Arikan K, Uysal O, Cetin G, Poyraz BC, Aksoy C, Bayar MR. Gender effect on attitudes towards the mentally ill: a survey of Turkish university students. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2007;44:57-61. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Sheridan D. College Students Attitudes Towards Mental Illness in Relation to Gender, Self-Compassion & Satisfaction with Life. Department of Psychology, DBS School of Arts. 2012;. |

| 36. | Corrigan PW, Edwards AB, Green A, Diwan SL, Penn DL. Prejudice, social distance, and familiarity with mental illness. Schizophr Bull. 2001;27:219-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 343] [Cited by in RCA: 301] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Corrigan PW, Shapiro JR. Measuring the impact of programs that challenge the public stigma of mental illness. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:907-922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 387] [Cited by in RCA: 284] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Corrigan PW, Morris SB, Michaels PJ, Rafacz JD, Rüsch N. Challenging the public stigma of mental illness: a meta-analysis of outcome studies. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63:963-973. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1101] [Cited by in RCA: 800] [Article Influence: 61.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Schomerus G, Angermeyer MC, Baumeister SE, Stolzenburg S, Link BG, Phelan JC. An online intervention using information on the mental health-mental illness continuum to reduce stigma. Eur Psychiatry. 2016;32:21-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |