CAREGIVING AND CAREGIVER-BURDEN

Caregiving has been defined as interactions, in which one person is helping another on a regular basis with tasks, which are necessary for independent living[1]. Anyone who provides some assistance to another who is, in some degree, incapacitated and needs help is a caregiver[2]. Normal “care” changes into “caregiving” when it is out of synchrony with the appropriate stage of the lifecycle. For family caregivers, this change takes place when the reciprocity between family members is out of balance, such that the responsibilities and tasks of one party in a relationship go beyond those customarily expected. Family caregivers are often bound by kinship obligations to adopt certain duties and responsibilities that are far in excess of those normally associated with a family role at a particular stage[3]. In doing so, they may perceive considerable distress, have a poor quality of life and experience psychological morbidity. The consequences of being related to and caregiving in chronic mental illness can, thus, be roughly divided into the obligation to offer long-term extensive care, and the emotional distress and worries related to the life-situation of the patient. Such consequences of caregiving are usually referred to as caregiver-burden or burden of care. Caregiver-burden has, thus, been defined as the ‘‘the presence of problems, difficulties or adverse events which affect the life (lives) of the psychiatric patients’ significant others (e.g., members of the household and/or the family)”[4]. Research over the last five decades or so has clearly established that having a family member with mental illness can lead to high levels of distress and burden for caregivers. Research on caregiver burden has also identified the major areas of (objective) burden, namely adverse effects on the household routine including care of children, disruption of relations within and outside the family, restriction of leisure time activities of caregivers, the strains placed on family finances and employment, the difficulties in dealing with dysfunctional and problem behaviours faced by caregivers, and the impact on mental and physical well-being of the caregivers. The prevalence of subjective psychological distress, often referred to as subjective burden, has also been found to be very high[5-15].

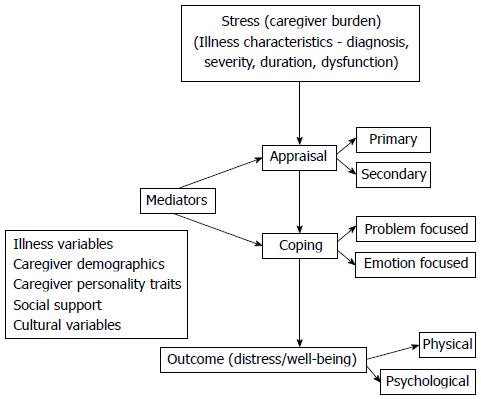

Studies on caregiver-burden have also gradually moved beyond simple enumeration of the problems faced by caregivers on account of the patient’s illness, to a consideration of the caregiving experience in its totality. The dominant model for examining the process of caregiving has been the stress-appraisal-coping paradigm of Lazarus and Folkman[16].

The “stress-appraisal-coping” theory suggests that the principal element of caregiving is an appraisal of its demands. The patient’s illness and its impact on the caregiver are the main sources of stress. Coping with this stress is determined by how it is appraised. Mediators of the process include social, demographic and cultural factors, caregiver’s personality traits, and the level of support they receive[17,18]. Thus, apart from identifying stressors, appraisal and coping as the central elements of the process of caregiving, this model also delineates certain mediators of this process. These mediators include illness variables (e.g., diagnosis, severity, duration of illness, duration of remission, cost of treatment), the caregivers’ socio-demographic and caregiving profile (e.g., gender, education, relation with the patient, amount of time spent with patient), personality attributes (e.g., neuroticism), socio-cultural factors which influence their attitudes towards caregiving, and the degree of social support available for the caregiver. These factors can influence appraisals, as well as the coping strategies adopted by the caregiver. Interactions between stressors, appraisals, coping, and the various mediators produce the eventual outcomes in terms of distress or well-being among caregivers[8,11].

Of all the mediators proposed by the “stress-appraisal-coping” model, ethnic and cultural factors have traditionally received the least research attention. This has changed over the last couple of decades or so with the advent of studies, which have clearly shown that culturally-defined values, norms, and roles are among the major determinants of the caregiving experience[10,11,13,19-31].

CULTURE, ETHNICITY AND CAREGIVING

Several strands of research can be identified in the broad area of the effects of culture and ethnicity on caregiver burden. The predominant methodology employed has been cross-cultural comparisons between caregivers of minority ethnic groups residing in Europe and the United States, and the native Caucasian population. The minority ethnic groups that have been the principal focus of such studies have included African-Americans, Afro-Caribbean, Latino or Hispanic groups, and Asian populations including Chinese, South Korean, Japanese and Indian caregivers[10-13,19-38]. This has been supplemented, to a limited extent, by research carried out among caregivers belonging to different cultures and residing in their countries of origin such as China, South Korea or India[12,13,28,30,39-45]. The examination of ethnic and cultural differences has encompassed virtually the whole spectrum of the caregiving experience. Consequently, it has investigated differences in caregiver burden and related factors such as service utilisation, cultural factors which could mediate these differences, and propounded theories, which could provide a coherent framework to understand these differences. Most of this research has been carried out among caregivers of elderly people with dementia or the physically frail elderly. Among “functional” psychiatric illnesses, schizophrenia has been the focus of research on ethnic or cultural differences in caregiving. Though the research data on schizophrenia appears to be qualitatively similar, the amount of data is, unfortunately, nowhere near the volume of research on dementia[12,46-48]. This is one significant deficiency of research in this area, which needs to be addressed.

CULTURAL DIFFERENCES IN CAREGIVING

There is a large body of comparative, cross-cultural research evidence, which clearly indicates that caregiving experiences vary across cultural and ethnic groups. For the most part, this research suggests that caregivers from a number of ethnic minority groups differ from their Caucasian counterparts in several respects.

Although the evidence is somewhat equivocal, there seems to be a slightly higher prevalence of caregiving among Asian-Americans, African-Americans, and Latinos, than among non-Hispanic Caucasians. Moreover, when controlling for the levels of disability, minority caregivers tend to provide more direct and informal care than do Caucasian caregivers[49]. Caucasian caregivers are most likely to provide care for a spouse; Latinos are the most likely to provide care for a parent; and African Americans are the most likely to be caring for other family members or unrelated individuals[50]. In general caregivers belonging to the ethnic groups such as African-Americans, Afro-Caribbean, Latino or Hispanic groups, and Asian communities such as the Chinese, Korean, Japanese and Indian caregivers report lower levels of caregiving stress and burden[10-13,20-31,33,47,51,52]. They are generally more tolerant of the mentally ill relative[32]. Subjective perceptions of burden appear to vary the most, while objective aspects of burden are more similar in nature[13,33,53]. This is mirrored by the finding of low levels of expressed emotions, particularly among Mexican-American and Indian families[6,12]. On the other hand, it has been shown that there is a higher level of stigma and negative conceptualisations of the illness[32,39]. This leads caregivers to try and keep the illness a secret and delay seeking treatment[31,32,34]. Differences have also been identified in the levels of social support available, appraisals of the caregiving situation and coping and help-seeking behaviour. Caucasian caregivers typically employ problem-solving and avoidance strategies more frequently than do African-American caregivers, perhaps because Caucasians perceive caregiving situations as a greater threat or stressor than do African-Americans. Moreover, African-American caregivers are more likely to view their situation in more positive terms, and draw upon religious faith and social networks to mitigate caregiving stress[11,13,21-23,29,52,54-57]. Caregivers from ethnic minority groups appear to have wider and stronger informal support networks than White caregivers[20-23,58,59]. The availability of greater informal support has been linked to the reduced use of formal services and low service utilisation among minority ethnic caregivers[60,61]. Consequently, caregivers from ethnic minorities cope with the stress of caregiving by turning to this readily available means of support from the family and the wider community[10,13,53]. They also seem to use more religious and spiritual methods of coping[57]. Apart from differences in negative outcomes of caregiving, a number of studies have also indicated a higher prevalence of positive aspects of caregiving and greater satisfaction from caregiving among caregivers from ethnic minority grou-ps[10,13,33,35,51,54,61]. However, the reliability of these cultural and ethnic differences in caregiving has often been compromised by methodological shortcomings and inconsistent findings across studies[19,24,51,52,55]. Moreover, socio-economic status, cultural differences, and within-group variability may confound research findings, making it more difficult to determine how ethnicity or culture differentially impacts the caregiving experience. It has been suggested that cultural or ethnic status may function as a proxy variable for other important factors that are more likely to impact caregiving experiences, such as income, education, health, and family structure[55]. This is not to suggest that ethnic minority status makes families immune to care related stressors. For example, ethnic minority caregivers also report worse physical health and more unhealthy behaviours than whites, after adjustment for socio-demographic differences[13,27]. Nevertheless, there seems to be hardly any doubt that the cultural context shapes the entirety of the caregiving experience and culturally-justified ideologies about roles, responsibilities, and coping shape the caregiving process[20-31]. This has often been referred to as the dimension of “cultural justification”; that is, the process by which caregivers call upon cultural norms and values, styles of communication and coping, and reliance on informal support systems to justify their role and responsibility as primary care providers for their chronically ill family members[26]. Variants of the stress -coping model, which incorporate cultural elements of caregiving have, thus, been proposed to account for these cultural and ethnic differences in caregiving.

FAMILIAL-CULTURAL FACTORS IN CAREGIVING

The list of potential cultural influences on the experience of caregiving is a long one. For sake of convenience, these factors can be divided into those pertaining to family values and norms such as familism, filial obligations or piety, family cohesion and solidarity, and other family values such as reciprocity between adult children and their parents, role modelling of caregiving behaviour for one’s own children, and religious and spiritual values emphasising an ethic to care for family members. The second group would include explanatory models of illnesses held by the caregivers and their attitudes towards mental illnesses. The third group would include coping styles, the influence of religion, and the influence of the wider community and social networks. Finally, factors such as acculturation and disadvantaged status could also be important, particularly for ethnic minority groups in the West[21,22,24,28-31].

Familism is a cultural value that refers to the strong identification and solidarity of individuals with their family as well as strong normative feelings of allegiance, dedication, reciprocity, and attachment to their family members, both nuclear and extended[29]. A review of caregivers from six American ethnic groups found highest levels of familism among most ethnic minority groups, compared to White American caregivers[62]. Thus, familism was representative of the individualism-collectivism dimension, and the differences on this measure reflected the effects of acculturation. It was further proposed that higher levels of familism would lead to a more benign appraisal of the stress of caregiving among ethnic minority groups, as it would reflect an underlying desire to provide care for family members[21]. This could explain why caregivers from ethnic minorities report caregiving as less stressful and burdensome. However, the hypothesis that higher levels of familism would result in less burden for caregivers from different cultural and ethnic groups was not borne out by subsequent research. Findings in this regard were mixed, and indicated that familism has a complex relation with caregiving, and the caregiving process may be influenced by numerous other factors[29,63-66]. One reason for such inconsistent results could be that familism is not a unitary construct. In fact, factor analysis has revealed three dimensions of the construct. These include familial obligation, a factor that reflects cultural values that demand caregiving for family members in need; perceived support from the family, a factor that measures cultural expectations that family members will be supportive in times of need; and family as referents, a factor that taps the value that sets up the family as a major source of rules and guidance for how life should be lived. These three dimensions appear to have independent and differing influences on the perception of burden. Accordingly, familism can have positive influences on caregiving distress when the family is perceived as a source of support. However, the dimensions of familism pertaining to a strong adherence to values regarding both feelings of obligation to provide support, as well as behaviours and attitudes that should be followed by different members of a family have been linked to increased caregiver burden and distress[29,63-66].

Filial piety or obligations is a common notion among Asian cultures including the Chinese and Indian people. It includes respect and care for elderly family members, which is explicitly taught to children from an early age. This family-centred cultural construct implies that adult children have a responsibility to sacrifice individual physical, financial, and social interests for the benefit of their parents or family. Filial piety has also been proposed to be a two-dimensional construct: behavioural (making sacrifices, taking responsibility) and emotional (harmony, love, respect). Although some studies have shown that high levels of filial piety make for lowered caregiving burden, this is not a consistent finding. Thus, similar to familism, the obligatory aspect of filial piety norms may constitute a source of stress for some caregivers belonging to ethnic minorities[28,29,31,37,44,67-70].

Another familial factor thought to have a significant impact on the process of caregiving is family cohesion, a process considered important for family functioning. It refers to the emotional bonding that family members have towards one another. Authors have described cohesion to comprise affective qualities of family relationships such as support, affection, and helpfulness[46,52,66,71]. Families with very high levels of cohesion, (“enmeshment”) often show communication patterns which are psychologically and emotionally intrusive or inhibitive commonly resulting in poor individuation and psychosocial maturity, whereas low levels of cohesion (“disengagement”) can lead to poor affective involvement within the family. Thus, optimal levels of family-cohesion are believed to be ideal for stable family functioning and proper caregiving, and this may differ among ethnic and cultural groups[46,66].

MODELS OF CAREGIVING AMONG DIFFERENT ETHNIC AND CULTURAL GROUPS

Initial attempts to explain differences in caregiving among ethnic minority groups in the West gave rise to the disadvantaged minority group model. This model proposed that because of the historically disadvantaged social history of minority ethnic groups, a number of unique stressors, resources, and vulnerabilities had emerged, which could influence caregiving experiences and caregiver well-being. Caregivers from minority ethnic groups would thus be suffering from the double jeopardy of being from a disadvantaged minority group and being exposed to the negative outcomes, which the caregiving role engenders. In this model, ethnicity was thought to reflect mainly disadvantaged minority status, which was often confounded by socioeconomic status. However, the data did not support this model. Although some studies suggested that differences in caregiving outcomes among minority ethnic groups could be explained by poor socio-economic conditions, the majority of the studies have found lower levels of caregiving burden and stress among ethnic groups such as African-Americans or Hispanics. Moreover, the model overlooked the positive aspects of caregiving, which were more commonly reported by caregivers from minority ethnic groups[29].

Thus, models based on the Lazarus and Folkman’s stress-coping approach were proposed instead. Differences in caregiving among diverse cultural groups were explained by a shared common core model, in which caregiving stressors lead to the appraisal of caregiving as burdensome and thus to poor health outcomes (see Figure 1). This model was originally proposed to explain caregiving outcomes in dementia, and was later extended to caregiving experiences with the frail elderly. More recently, this model has provided a framework for examining caregiving in other psychiatric illnesses such as schizophrenia[11,29,31].

Figure 1 A simplified depiction of the stress-appraisal-coping model of caregiving.

The cultural variant of this stress-coping model was first proposed by Aranda et al[21]. These authors based their observations on Latino caregivers and concluded that the dimension of individualism vs collectivism, or familism, explained the differences in caregiving among different ethnic and cultural groups. They further proposed that cultural influences such as familism operate at the level of appraisals of burden. Consequently, higher levels of familism would lead to more benign appraisals of burden, and also to different patterns of using social support, and coping styles, and eventually to lowered perceptions of caregiving as burdensome. Subsequent research on cultural influences in caregiving did not support the predominant role of familism in explaining cultural differences. Other factors such as filial obligations were also felt to be important. Moreover, a single dimension of caregiving from individualism to familism was not found sufficient to explain cultural differences in caregiving. The influence of cultural factors seemed to be more on coping than appraisals of caregiving stress. Therefore, a revised socio-cultural stress-coping model has been proposed[29,31,66]. In this model the impact of cultural influences on caregiving is smaller, more group specific, and varied in direction of effect than anticipated. Moreover, cultural differences appear to operate at the level of coping with caregiving stress and the social support available for the caregiver, rather than appraisals of burden.

METHODOLOGICAL AND CONCEPTUAL ISSUES

The research thus far has clearly demonstrated that there are obvious cultural differences in the experience of caregiving. It has also identified potential cultural factors of interest and proposed models to explain their influence. However, things are far from clear and findings are far from consistent.

One reason for the inconsistent and uncertain nature of the findings could be methodological problems, which affect quite a few of the studies[21,23,24,27,29,55]. Many studies have used purposive or convenience sampling, and the numbers included have often been too small to reach definitive conclusions. Non-caregiving controls have not been used often. Only about half the studies have incorporated conceptual frameworks and models for examining burden and related variables. In certain areas such as caregiver burden, established measures have been mostly used, while in other domains such as social support or coping, there is a great deal of variability and heterogeneity in the measures used[24]. The cross-cultural relevance of the measures used is another problem, which needs to be addressed[23].

In addition, it is becoming increasingly clear that cultural influences are highly complex and multi-dimensional. They are also quite group specific. For example, Dilworth-Anderson et al[24] found that White caregivers were significantly more depressed and burdened than African-American caregivers, while Hispanic and White caregivers experienced higher levels of role strain compared to African-Americans. Similarly, Japanese and Mexican-American caregivers reported significantly more psychiatric distress than did White and African-Americans[35,36,64].

Moreover, there appears to be substantial within-group heterogeneity among caregivers, which complicates the accurate attribution of differences among caregivers to specific aspects of their group membership[23]. Cultural values and norms are not static entities; instead they can change from one generation to the next because of the influence of urbanisation, globalisation and acculturation[13,61,72]. The interactions between cultural values and other factors such as gender are also complex. For example, Indian and Chinese studies have shown that effects of filial piety and other traditional values could differ between the genders. Women who adhered to notions of filial piety and Asian cultural values regarding family obligations were more likely to perceive greater burden than men who adhered to the same notions[37,45,68]. Finally, most studies have examined family factors on the dimension of familism (or collectivism) to individualism. Other dimensions of potential importance, such as the difference between shame and guilt cultures, have not received as much attention. There is some evidence to indicate that shame and stigma of mental illness may have more negative effects on Asian caregivers, and prevent them from accessing services[30,34,72,73]. Such evidence indicates the need to examine all possible dimensions, which might explain cultural differences in caregiving.

TASKS AHEAD

Despite the theoretical and methodological problems, the foundations of a culturally based framework of caregiving in chronic psychiatric illnesses appear to have been laid. Research on cultural differences in caregiving has important implications for caregivers and the professionals involved in assisting them. An understanding of the role of culture in caregiving is an essential first step, and it can be hoped that future research will help unravel the complexities of this association. Findings of such research could also be utilised to inform professionals working with culturally diverse groups of caregivers, so that they are more sensitive to the unique needs of these families. Moreover, the results could be used to guide the efforts to devise culturally adapted versions of interventions to reduce caregiver burden and distress[28-31]. It is for these very reasons that research in this area needs to continue. More pertinently, there is a greater need for research on cultural aspects of caregiving from Asian and other non-Western countries, on lines of the research among ethnic minorities in the West. Finally, other chronic psychiatric illnesses such as schizophrenia and mood disorders also merit examination of cultural aspects of caregiving among them.