Published online Sep 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i9.110536

Revised: June 24, 2025

Accepted: July 8, 2025

Published online: September 19, 2025

Processing time: 79 Days and 1.4 Hours

Depression is highly prevalent among postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, driven by the combined effects of hormonal changes, reduced bone density, and psychosocial stress. A recent study by Cui and Su reported that 73.3% of affected women exhibited depressive symptoms, with low bone mineral density, chronic comorbidities, and reduced serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine) levels as key risk factors. Notably, nurse-led psychological interventions improved both mood and quality of life. This editorial underscore the need to integrate mental health support into standard osteoporosis care. Simple, scalable strategies such as routine screening and nurse-delivered emotional support may help bridge the gap between physical and psychological health. These approaches are especially relevant for aging populations across diverse healthcare settings. A dual focus on bone and emotional well-being is essential to improving outcomes in this vul

Core Tip: Depression and osteoporosis frequently co-occur in postmenopausal women, compounding health risks and reducing quality of life. This editorial highlight recent findings that link low bone mineral density, chronic disease, and low serotonin levels with depressive symptoms, while demonstrating the effectiveness of specialized psychological nursing interventions. Integrating emotional and physical care enables clinicians to support postmenopausal women in achieving both psychological well-being and skeletal integrity.

- Citation: Zhu JY, Yiming A, Zeng JQ. Depression in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis: Integrating psychological nursing into holistic care. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(9): 110536

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i9/110536.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i9.110536

The co-occurrence of osteoporosis and depression in postmenopausal women has emerged as a significant public health concern. Osteoporosis affects over 200 million people globally, leading to fractures, chronic pain, and loss of independence among older adults, while depression remains a leading cause of disability in this demographic[1]. Postmenopausal women are particularly vulnerable, as estrogen deficiency disrupts both bone metabolism and serotonergic signaling, increasing the risk of skeletal fragility and mood disorders[2].

When osteoporosis and depression coexist, they can form a vicious cycle. Fracture-related pain and mobility loss may lead to isolation and depression. In turn, depression reduces physical activity, appetite, and treatment adherence, which worsens bone loss[3,4]. Recent epidemiological data estimate that nearly one in three postmenopausal women experiences depressive symptoms, with rates substantially higher among those diagnosed with osteoporosis[5].

Despite the well-documented bidirectional relationship, the mental health aspect of osteoporosis remains underrecognized in clinical practice. Care models continue to treat bone fragility and psychological well-being as separate domains, missing opportunities for more holistic, patient-centered management. Against this backdrop, the study by Cui and Su[6] offers timely insights. Their investigation not only quantifies the prevalence and predictors of depression among osteoporotic women but also evaluates the impact of nurse-delivered psychological interventions. This research underscores the growing need to embed mental health strategies within routine osteoporosis care, particularly for aging populations.

In a retrospective analysis of 180 Chinese women aged 45 to 75, Cui and Su[6] confirmed what smaller-scale studies had previously implied: Depression is strikingly prevalent among women with osteoporosis, affecting 73.3% of their study population. Their multivariate analysis identified three independent risk factors for depression: Significantly low lumbar or femoral bone mineral density (BMD), the presence of chronic comorbidities, and reduced serum serotonin [5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)] levels. On the positive side, two modifiable protective factors were highlighted consistent calcium supplementation and regular engagement in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity.

To address these psychosomatic dynamics, the authors implemented a six-part psychological nursing program over the course of several weeks. The intervention targeted postmenopausal women aged 45-75 with osteoporosis and depressive symptoms (defined as a Hamilton depression rating scale score > 8). It was delivered by certified nursing staff trained in psychological counseling. The program included targeted health education, structured emotional counseling, personalized exercise coaching, dietary guidance, biochemical monitoring, and functional rehabilitation. While no additional outcome tools beyond the 24-item Hamilton depression rating scale were reported, the intervention demonstrated significant reductions in depression scores. These findings are consistent with earlier studies, such as that by Huang et al[7] which documented the positive impact of psychological nursing in reducing anxiety and depressive symptoms among elderly patients recovering from osteoporotic fractures.

The significance of Cui and Su’s findings lies in three areas[6]. First, incorporating biochemical markers like serotonin into nursing-led studies remains relatively novel within psychosocial intervention research. Second, their study demonstrates that specialized, nurse-led interventions can deliver effective biopsychosocial care that is, care which addresses the biological, psychological, and social dimensions of a patient’s health without significantly increasing resource demands or workload. Finally, the alignment between identified risk factors and existing pathophysiological literature enhances the external validity of their findings, supporting broader implementation across clinical settings.

This structured, nurse-led program reflects a pragmatic integration of psychosocial care into standard osteoporosis management, serving as a preliminary framework that can be adapted across clinical contexts. Its emphasis on modifiable factors offers a feasible, scalable approach, particularly suitable for aging populations and resource-limited healthcare systems. To support implementation, routine osteoporosis visits could incorporate brief psychological screenings, nurse-delivered emotional support, and clear referral pathways to mental health services, forming a practical foundation for multidisciplinary care.

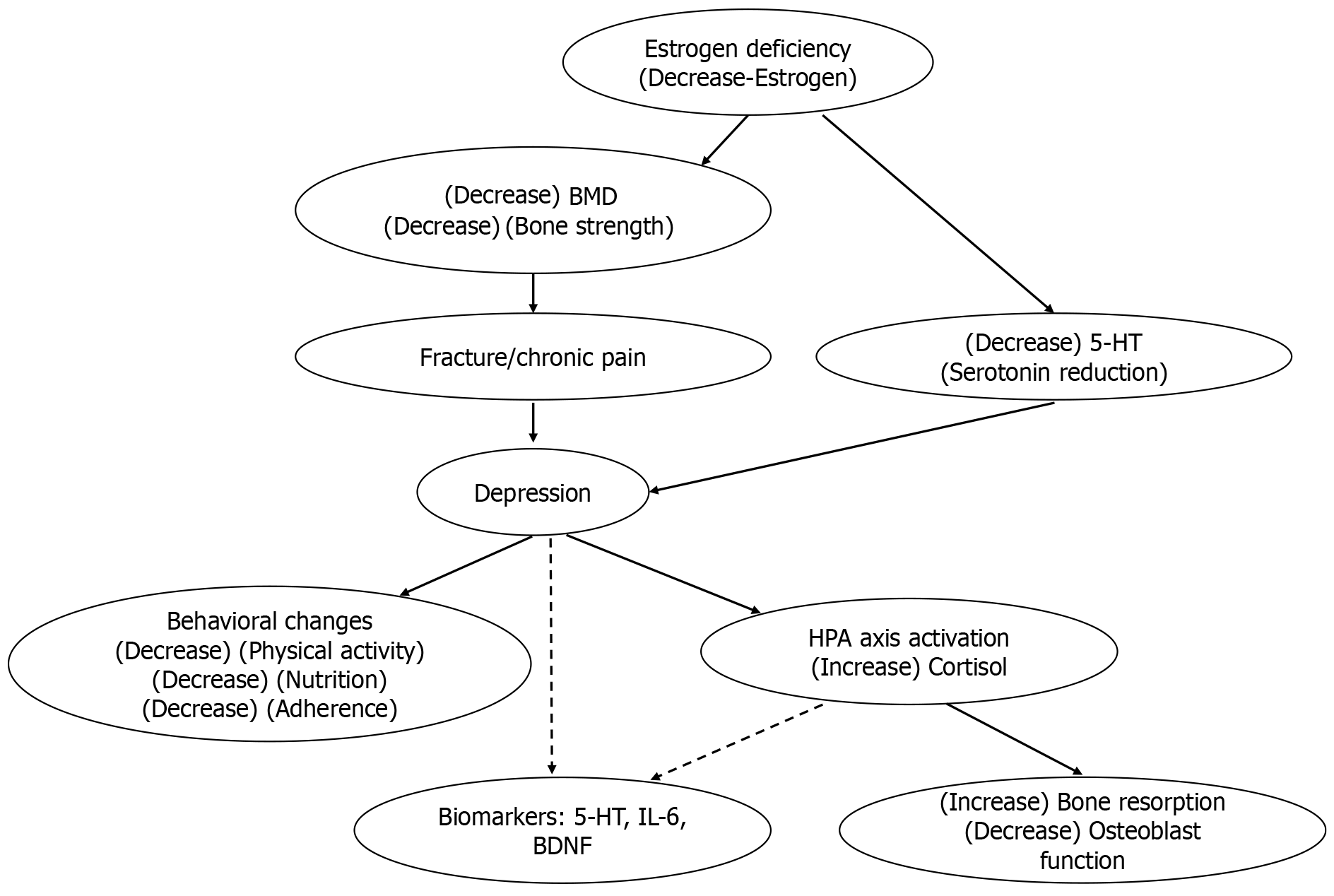

Cui and Su’s study[6] underscores a profound biological and behavioral entanglement between osteoporosis and depression, extending well beyond simple co-occurrence. Estrogen deficiency following menopause disrupts serotonergic signaling and bone remodeling two critical pathways essential for mood regulation and skeletal integrity[8]. Concurrently, chronic psychological stress activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, elevating systemic cortisol levels, suppressing osteoblast function, and accelerating bone resorption[9].

Behavioral dynamics further compound this biological complexity. Depression often diminishes patients’ motivation to engage in physical activity, maintain balanced nutrition, and adhere to medical treatments key behaviors crucial for preserving bone density[10]. Conversely, osteoporotic fractures frequently lead to chronic pain, reduced mobility, and social isolation, exacerbating depressive symptoms and perpetuating a difficult-to-break vicious cycle through conventional monodisciplinary care[11].

This reciprocal relationship is captured in the conceptual model presented in Figure 1, which illustrates the crosstalk between psychological and skeletal health. Estrogen withdrawal lowers BMD and 5-HT levels, both associated with mood disturbances, while depression aggravates bone loss via HPA axis hyperactivity and behavioral deterioration. Emerging evidence also implicates inflammatory markers such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) as mediators in this psychoneuroendocrine loop-a dynamic feedback system linking psychological states, the nervous system, and hormonal responses to stress[12]. These interconnected mechanisms form a feedback system in which biological and behavioral factors reinforce each other. Psychological nursing interventions, by reducing stress, promoting physical activity, and improving treatment adherence, may indirectly modulate this loop-supporting both mood regulation and bone health.

Pharmacologic treatment of depression introduces additional clinical complexity. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), widely prescribed for older adults, are increasingly recognized to elevate fracture risk significantly. A 2020 meta-analysis by Kumar et al[13] reviewed 37 observational studies, revealing a robust association between SSRI use and fracture risk (pooled relative risk = 1.62; 95% confidence interval: 1.52-1.73), persisting across diverse geographic regions, durations of drug use, and fracture sites. Supporting these findings, a comprehensive 2022 review by de Filippis et al[14], including data from over 15 million adults, confirmed a consistent elevation in both hip and vertebral fracture risks among chronic SSRI users.

Collectively, these findings strongly advocate for incorporating non-pharmacological interventions, particularly psychological nursing, as either adjuncts or alternatives for managing depression in patients at heightened osteoporotic risk. An integrated multidisciplinary approach combining behavioral support, vigilant skeletal monitoring, and personalized care planning could effectively mitigate the unintended skeletal consequences of prolonged antidepressant use, enhancing both emotional resilience and physical health.

The study by Cui and Su[6] provides valuable insights into the interplay between osteoporosis and depression, but also highlights critical research gaps-especially in the context of a rapidly aging global population. With the number of individuals aged 60 and above expected to reach 2 billion by 2050, bridging the divide between skeletal and mental health is not only timely but essential.

First, the study’s single-center, retrospective design limits generalizability. Conducted in eastern China, its findings may not translate across populations with diverse cultural norms, healthcare systems, or attitudes toward aging and menopause. Cross-cultural studies are needed to explore how stigma, social support, and family structure influence comorbid depression in osteoporotic women.

Second, the cross-sectional nature of the study restricts causal inference. It remains unclear whether low BMD precedes depression, or vice versa. Prospective, longitudinal studies-supplemented by Mendelian randomization, as demonstrated by Guo et al[2] can help unravel causality. Future research should also integrate biomarkers such as 5-HT, cortisol, IL-6, and BDNF to identify shared molecular pathways. Animal models may further elucidate whether targeting depressive symptoms can decelerate bone loss.

Third, although the six-part psychological nursing model is promising, its long-term efficacy, adherence, and scalability remain uncertain. Variability in patient literacy, comorbidities, and digital access may affect real-world impact. Randomized controlled trials are essential, as are innovations like app-based counseling and remote health tracking to expand reach in underserved communities.

Finally, effective management requires interdisciplinary collaboration. Osteoporosis care traditionally siloed in endocrinology or orthopedics must integrate mental health screening, shared psychiatric referral pathways, and team-based planning. As Kumar et al[13] cautioned, the fracture risk associated with SSRIs underscores the need for non-pharmacological and coordinated strategies.

In sum, future research should be biologically grounded, behaviorally informed, and clinically integrated-building a holistic framework to support aging women at the nexus of mind and bone.

As the global population ages, the intersection of osteoporosis and depression in postmenopausal women demands greater clinical and research attention. Addressing mental health is not ancillary to bone care-it is central to improving outcomes. Psychological nursing interventions offer a low-cost, scalable solution that enables frontline providers to deliver holistic, person-centered care. Moving forward, healthcare systems must prioritize integrated screening, interdisciplinary collaboration, and culturally adaptable interventions. Bridging physical and psychological care is not only more humane it is more effective. The time has come to replace parallel care tracks with a shared roadmap that strengthens both bones and minds. Policymakers and clinical guidelines may consider incorporating psychological screening and nurse-led emotional care as integral components of osteoporosis treatment protocols.

| 1. | Chen K, Wang T, Tong X, Song Y, Hong J, Sun Y, Zhuang Y, Shen H, Yao XI. Osteoporosis is associated with depression among older adults: a nationwide population-based study in the USA from 2005 to 2020. Public Health. 2024;226:27-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Guo X, She Y, Liu Q, Qin J, Wang L, Xu A, Qi B, Sun C, Xie Y, Ma Y, Zhu L, Tao W, Wei X, Zhang Y. Osteoporosis and depression in perimenopausal women: From clinical association to genetic causality. J Affect Disord. 2024;356:371-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kelly RR, McDonald LT, Jensen NR, Sidles SJ, LaRue AC. Impacts of Psychological Stress on Osteoporosis: Clinical Implications and Treatment Interactions. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Shi L, Zhou X, Gao Y, Li X, Fang R, Deng X. Evaluation of the correlation between depression and physical activity among older persons with osteoporosis: a cross-sectional study. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:1193072. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Li J, Liu F, Liu Z, Li M, Wang Y, Shang Y, Li Y. Prevalence and associated factors of depression in postmenopausal women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2024;24:431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cui QM, Su YF. Investigation of depressive symptoms in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis, specialized psychological nursing intervention measures, and key point analysis. World J Psychiatry. 2025;15:104974. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Huang L, Zhang C, Xu J, Wang W, Yu M, Jiang F, Yan L, Dong F. Function of a Psychological Nursing Intervention on Depression, Anxiety, and Quality of Life in Older Adult Patients With Osteoporotic Fracture. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2021;18:290-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rosenblat JD, Gregory JM, Carvalho AF, McIntyre RS. Depression and Disturbed Bone Metabolism: A Narrative Review of the Epidemiological Findings and Postulated Mechanisms. Curr Mol Med. 2016;16:165-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Azuma K, Adachi Y, Hayashi H, Kubo KY. Chronic Psychological Stress as a Risk Factor of Osteoporosis. J UOEH. 2015;37:245-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hlis RD, McIntyre RS, Maalouf NM, Van Enkevort E, Brown ES. Association Between Bone Mineral Density and Depressive Symptoms in a Population-Based Sample. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79:16m11276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sale JEM, Gignac M, Frankel L, Thielke S, Bogoch E, Elliot-Gibson V, Hawker G, Funnell L. Perspectives of patients with depression and chronic pain about bone health after a fragility fracture: A qualitative study. Health Expect. 2022;25:177-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Porter GA, O'Connor JC. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and inflammation in depression: Pathogenic partners in crime? World J Psychiatry. 2022;12:77-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 35.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 13. | Kumar M, Bajpai R, Shaik AR, Srivastava S, Vohora D. Alliance between selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and fracture risk: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;76:1373-1392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | de Filippis R, Mercurio M, Spina G, De Fazio P, Segura-Garcia C, Familiari F, Gasparini G, Galasso O. Antidepressants and Vertebral and Hip Risk Fracture: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Healthcare (Basel). 2022;10:803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |