Published online Sep 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i9.110352

Revised: June 25, 2025

Accepted: July 21, 2025

Published online: September 19, 2025

Processing time: 83 Days and 1.3 Hours

This letter critically reviews a recent longitudinal network study by Bai et al examining the dynamic, symptom-level interplay among peer bullying victimization, depression, anxiety, and aggression in Chinese adolescents. The study highlights that key symptoms, such as persistent sad mood, sleep disturbances, and cyberbullying victimization play a pivotal role in reinforcing the vicious cycle between mental health issues and bullying experiences. While the application of cross-lagged panel network analysis offers a nuanced understanding of these bidirectional relationships, several limitations remain, including the use of self-reported measures and a region-specific sample. Nevertheless, the findings underscore the urgent need for early screening and targeted interventions in school settings, particularly those addressing both emotional symptoms and digital forms of bullying. Moving forward, integrated and culturally sensitive approaches are essential to prevent escalation and break the link between peer victimization and adolescent psychopathology. Future research should incorporate multi-informant data and broaden the cultural context to strengthen generalizability and intervention design.

Core Tip: Bai et al’s study demonstrates that specific symptoms especially sad mood, sleep disturbance, and cyberbullying victimization drive the reciprocal relationship between peer bullying and adolescent mental health problems. This finding calls for early, symptom-focused interventions and comprehensive school-based strategies that address both traditional and cyber forms of bullying. For lasting impact, future research and prevention efforts should prioritize multi-source data and culturally adaptable approaches.

- Citation: Byeon H. Tracing the hidden links between sadness, aggression, and peer victimization in adolescents. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(9): 110352

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i9/110352.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i9.110352

Adolescence is a period characterized by rapid cognitive, emotional, and social development, during which interactions within peer groups are known to have a profound impact on an individual’s mental health. At this stage, students exhibit heightened sensitivity to peer approval and social status, as well as increased emotional instability[1]. As a result, adolescents are particularly vulnerable to repeated aggressive behaviors within their peer groups, known as peer bullying victimization (PBV)[2]. Bullying can manifest in various forms including physical, verbal, social, and more recently, cyberbullying through online platforms[3] all of which can have serious consequences for the victim’s mental health.

Theoretically, a close interplay has been reported between PBV and mental health problems such as depression, anxiety, and aggression. Previous studies[4,5] have found that PBV not only increases the risk of internalizing problems (such as depression and anxiety), but also externalizing problems (such as aggression). For example, adolescents who experience bullying are more likely to develop depressive disorders or anxiety disorders[4], and some may express their distress outwardly through aggressive behaviors. More recent research[6,7] has demonstrated that these relationships are not unidirectional; rather, there are reciprocal influences at play. That is, adolescents with internalizing or externalizing problems may become more susceptible to victimization within their peer group, while experiences of victimization can, in turn, exacerbate these psychological issues. Furthermore, the emergence of new forms of bullying such as cyberbullying[8] has drawn increasing attention to the impact of digital harassment on adolescent mental health.

Against this backdrop, the recent longitudinal study by Bai et al[9] transcends variable-centred approaches by applying symptom-level cross-lagged panel network analysis to clarify how depression, anxiety, aggression and PBV influence one another over time. In this Letter, we offer a focused commentary on their work, distilling the study’s key findings, evaluating its methodological strengths and limitations, and explaining how the newly identified intervention targets sad mood, sleep disturbance and cyberbullying victimization can be translated into school-based screening and prevention programmes. By weaving current evidence with practical considerations, we aim to equip clinicians, educators and policy-makers with actionable recommendations that advance both scholarship and frontline practice in adolescent mental health.

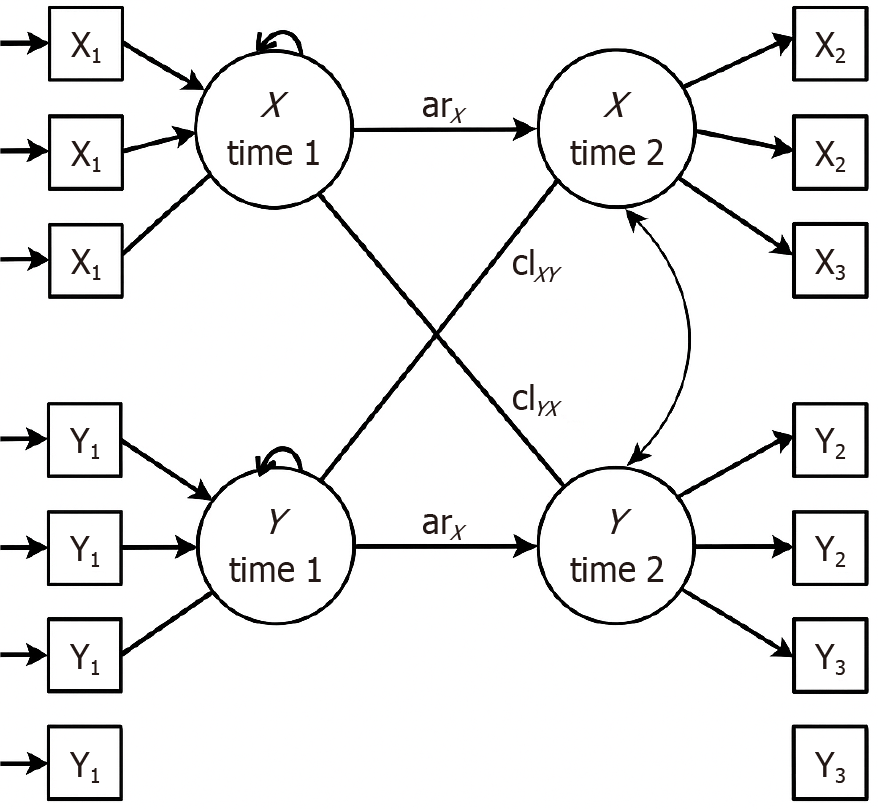

The study by Bai et al[9] investigated the relationships between PBV, depression, anxiety, and aggression in 1260 Chinese middle school students over six months using cross-lagged panel network analysis (Figure 1). The findings indicated that “persistent sad mood”, a symptom of depression, was the strongest predictor of both PBV and aggression. Cyberbullying victimization significantly influenced depression and anxiety, while anxiety had a weak effect on PBV. Aggression was mainly affected by depressive symptoms and sleep disturbances, with physical bullying driving the PBV-aggression interaction. The authors suggest prioritizing sad mood, sleep disturbance, and cyberbullying in interventions.

The study’s strengths include using symptom-level network analysis, which provides detailed insights into specific symptom interplay relevant for clinical targets, unlike previous studies[4,5] focusing on broader correlations. It also comprehensively examined the reciprocal and longitudinal relationships among depression, anxiety, aggression, and PBV, offering a dynamic understanding compared to research[4,5] on single variables. Furthermore, the study’s incorporation of cyberbullying as a primary independent variable reflects its growing significance in adolescence and its distinct impact on mental health[3,8].

However, the study has limitations. The sample was geographically limited, requiring caution when generalizing to diverse adolescent populations. Relying solely on self-report data from students may have introduced biases due to socially desirable responses or memory errors, suggesting a need for multi-informant data in the future. The two-time-point data collection limited the ability to fully understand temporal changes and causal relationships, necessitating more frequent assessments over longer periods. The correlation stability coefficient of 0.21 was below the recommended threshold, warranting cautious interpretation of some results. Finally, the lack of reports from other informants limited a comprehensive assessment of mental health and social behaviors, highlighting the need for multi-informant approaches in future research.

This study presents important implications that can be directly applied in clinical and school settings, making its clinical and academic significance considerable. First, the results clearly demonstrate that key symptoms, such as sad mood, sleep disturbance, and cyberbullying victimization play a central role in the cyclical worsening of PBV and mental health problems. Therefore, in both clinical and school settings, it is crucial to identify these core symptoms early and prioritize them as intervention targets to break the vicious cycle of mental health deterioration. To implement this, it is essential to establish regular and systematic mental health screening programs at the school level, and to build a multidisciplinary collaborative system that enables rapid referral of high-risk students to professional counseling and treatment. In addition, it is important for teachers, school counselors, and parents to cooperate closely and receive practical education, so they can sensitively recognize changes and warning signs in students.

Second, the study found that cyberbullying affects adolescent depression and anxiety in ways that are distinct from traditional offline bullying. Cyberbullying, due to its digital nature including anonymity, rapid dissemination, and persistence creates an environment where victims can become more isolated and psychologically pressured[10]. Based on these findings, schools and communities should go beyond basic internet safety education and implement systematic digital citizenship education and comprehensive programs for the prevention and response to cyberbullying. These efforts should be integrated not only into classroom teaching but also into online communities and social media platforms, covering responsible communication, risk signal recognition, reporting, and support systems. Schools should establish clear anti-cyberbullying policies and procedures, provide easily accessible anonymous reporting systems and professional counseling services, and enhance collaboration and information sharing with parents.

Third, the study specifically confirmed that sleep disturbances are closely linked not only to aggression but also to a variety of other mental health issues. In clinical practice, many adolescents who report sleep problems also struggle with emotional instability, impulsivity, and interpersonal difficulties[11]. Therefore, it is necessary to operate sleep hygiene education programs targeting both students and parents, emphasizing the importance of healthy sleep habits and providing concrete behavioral guidelines that can be implemented in daily life. Furthermore, schools should adopt a holistic approach to improve lifestyles that negatively impact sleep, such as excessive studying hours and overuse of smartphones.

Fourth, the research suggests that deficiencies in emotional regulation and impulse control may lead to peer conflict, aggression, and ultimately, the worsening of mental health. Accordingly, in actual school settings, various psychological education and group counseling programs aimed at developing social and emotional competencies such as emotional regulation, stress management, and impulse control should be regularly conducted. For students showing warning signs, a support system should be in place to provide more in-depth individual therapy. These programs should not be limited to at-risk students but should be expanded as universal preventive approaches targeting all students for greater effectiveness.

I would like to offer several concrete suggestions for future research and policy development. First, to overcome the limitation that the main findings of this study may be restricted to certain regions and cultures, similar studies should be replicated across diverse cultural backgrounds and regions. This will help identify universal mechanisms of adolescent mental health and peer interactions, and enhance the generalizability of research results. In particular, multicultural comparative studies that systematically analyze the effects of social environments and educational systems on research outcomes should be actively promoted.

Second, to better understand the multidimensional nature of adolescent mental health problems, it is essential to integrate observational and report data from various sources including parents, teachers, and peers. By triangulating behavioral and emotional signals that are difficult to capture with self-report alone, more comprehensive and reliable data can be obtained. This, in turn, will enable a more precise evaluation of intervention effectiveness.

Third, it is necessary to actively develop and evaluate tailored intervention programs that specifically target the core symptoms identified in this study, such as sad mood, sleep disturbances, and cyberbullying victimization. In addition to general intervention programs, practical research and field-based interventions focusing on these key symptoms should be systematically implemented for early detection, prevention, and treatment.

Fourth, under a close collaborative system between schools and local communities, it is necessary to build a system that can provide multi-layered and integrated psychological support services for students exposed to various risk factors. To achieve this, networks with education authorities, public health centers, mental health welfare centers, and local counseling agencies should be activated, and a seamless management system encompassing crisis intervention and post-crisis support should be established. These efforts will not only enhance students’ individual resilience but also contribute significantly to creating a healthy and safe school environment.

The study by Bai et al[9] is a valuable longitudinal study that empirically demonstrates the practical potential of symptom-focused network analysis and the importance of clinical intervention targets in the field of adolescent mental health. It is hoped that the implications presented in this study will be widely applied in clinical and school settings, contributing to the improvement of adolescent mental health. Furthermore, it is anticipated that the accumulation of such research will lead to the development of more precise and effective prevention and treatment strategies in the future.

| 1. | Halyna G, Lyubov D. Psychological factors of emotional instability in adolescents. Int J Innov Technol Soc Sci. 2021;4:414318. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 2. | Seon Y, Smith-Adcock S. Adolescents’ meaning in life as a resilience factor between bullying victimization and life satisfaction. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2023;148:106875. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Waasdorp TE, Bradshaw CP. The overlap between cyberbullying and traditional bullying. J Adolesc Health. 2015;56:483-488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 17.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Dantchev S, Hickman M, Heron J, Zammit S, Wolke D. The Independent and Cumulative Effects of Sibling and Peer Bullying in Childhood on Depression, Anxiety, Suicidal Ideation, and Self-Harm in Adulthood. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kelly EV, Newton NC, Stapinski LA, Slade T, Barrett EL, Conrod PJ, Teesson M. Suicidality, internalizing problems and externalizing problems among adolescent bullies, victims and bully-victims. Prev Med. 2015;73:100-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Liao Y, Chen J, Zhang Y, Peng C. The reciprocal relationship between peer victimization and internalizing problems in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Acta Psychol Sin. 2022;54:828-849. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Siennick SE, Turanovic JJ. The longitudinal associations between bullying perpetration, bullying victimization, and internalizing symptoms: Bidirectionality and mediation by friend support. Dev Psychopathol. 2024;36:866-877. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Li C, Wang P, Martin-Moratinos M, Bella-Fernández M, Blasco-Fontecilla H. Traditional bullying and cyberbullying in the digital age and its associated mental health problems in children and adolescents: a meta-analysis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2024;33:2895-2909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 40.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bai YP, Yuan H, Yu QY, Liu LM, Wang WC. Longitudinal study of peer bullying victimization and its psychological effects on adolescents. World J Psychiatry. 2025;15:104145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Smith D, Leonis T, Anandavalli S. Belonging and loneliness in cyberspace: impacts of social media on adolescents’ well-being. Aust J Psychol. 2021;73:12-23. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | McGowan NM, Goodwin GM, Bilderbeck AC, Saunders KEA. Actigraphic patterns, impulsivity and mood instability in bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder and healthy controls. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2020;141:374-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |