TO THE EDITOR

Pelvic fractures are significant injuries that can result from various traumatic events, including high-energy impacts such as motor vehicle collisions, falls from significant heights, and crush injuries. These fractures can range from stable, low-energy injuries to complex, unstable fractures associated with substantial hemorrhage and life-threatening complications[1]. The management of pelvic fractures requires a multidisciplinary approach, involving trauma surgeons, orthopedic specialists, interventional radiologists, and critical care teams. Advancements in surgical techniques, including minimally invasive approaches, have improved outcomes by reducing operative time, blood loss, and postoperative complications. Early recognition and appropriate management are crucial to minimize morbidity and mortality associated with these injuries[2,3].

Pelvic fractures, particularly when associated with lumbosacral plexus injuries, constitute severe forms of trauma with far-reaching consequences. Beyond the obvious musculoskeletal implications, these injuries frequently disrupt neurovascular structures and induce significant psychological distress.

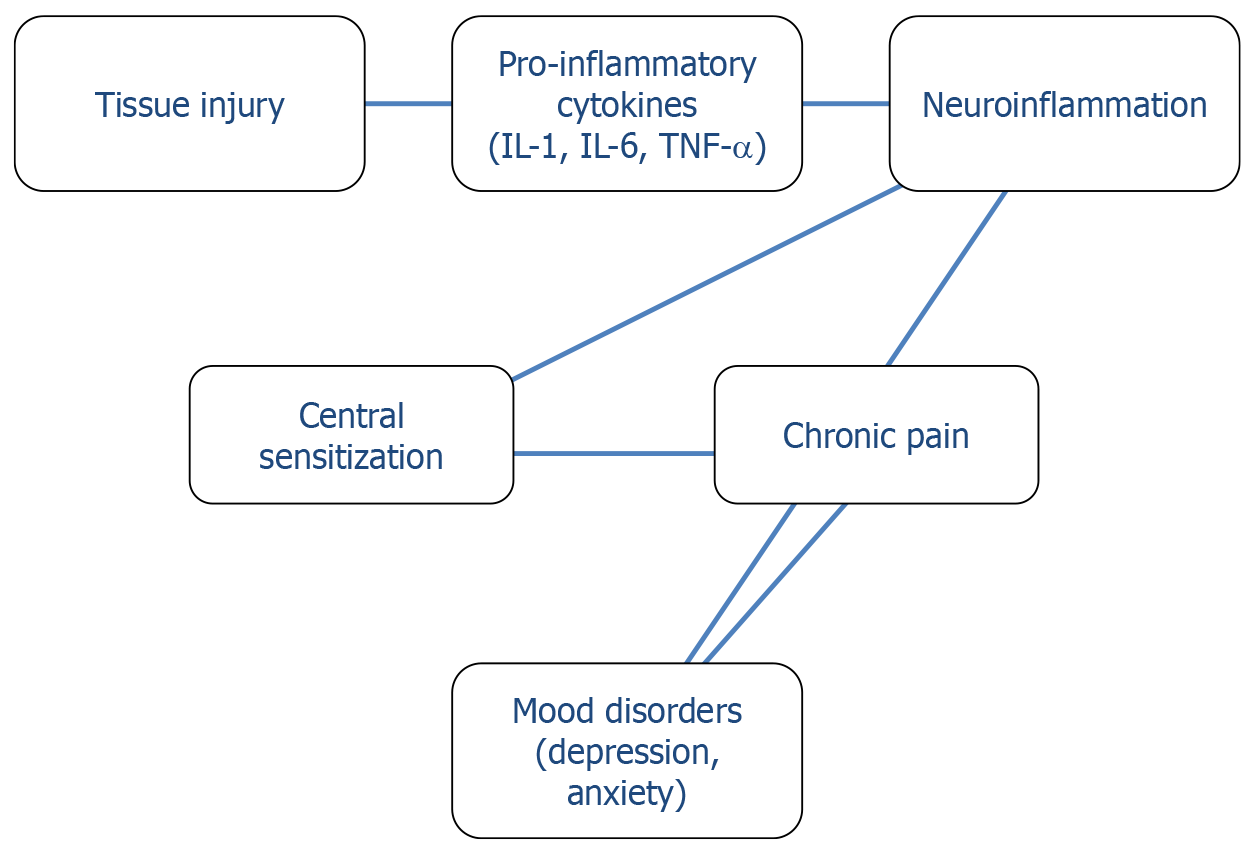

Alterations in the bidirectional communication pathways between the central nervous system (CNS) and peripheral immune system are involved in the etiology of pathologic pain conditions. In fact, both psychiatric illnesses and chronic pain states are characterized by enhanced and prolonged proinflammatory signaling in the CNS[4]. Complex neuroimmune pathways linking pain, inflammation, and psychological distress, shape altered nociceptive mechanisms, physiological and behavioral changes (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Neuroimmune pathways linking pain, inflammation, and psychological distress.

IL-1: Interleukin-1; IL-2: Interleukin-2; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor-α.

The link between orthopedic trauma and psychiatric sequelae is well established, with anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) reported in a substantial portion of patients. In particular, depressive symptoms have been reported in 13% to 56% of patients who have sustained orthopedic trauma, while 20%-51% of patients following orthopedic injury experience PTSD. Quality-of-life assessments show lower scores in patients with higher psychological distress. In addition, PTSD can have a significant impact on outcomes, including the development of chronic pain, and it has been observed that people with PTSD often have co-occurring conditions, such as depression, substance use, or one or more anxiety disorders[5,6]. The occurrence of social and economic burden can negatively affect patients’ recovery and reintegration into society.

TRAUMA RECOVERY

The recent study by Yang et al[7] represents a significant contribution to our understanding of how surgical technique influences not only physical recovery, but also psychological well-being.

Yang et al[7] conducted a retrospective study involving 136 patients with pelvic fractures complicated by lumbosacral plexus injuries, all treated via a transrectus lateral approach. Patients were selected based on strict inclusion criteria confirming posterior pelvic ring instability with nerve injury and excluded if they had previous abdominal surgeries or required combined surgical approaches. Outcome measures included psychological assessments through the Self-rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and Self-rating Depression Scale (SDS)[8], pain via Numerical Rating Scale[9], sleep quality through the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)[10], and motor function using the Medical Research Council scale[11].

The authors demonstrate that the transrectus lateral approach, a minimally invasive method, leads to substantial improvements in anxiety, depression, sleep quality, and pain-critical dimensions of recovery that are often undervalued in trauma care. While the study provided valuable clinical and psychological insights, its retrospective nature, single-center design, reliance on self-reported questionnaires, and focus solely on Chinese patients introduce potential limitations, including recall bias and limited generalizability. Besides, the specific length of the follow-up period is not detailed in the manuscript. This absence limits the ability to evaluate the long-term durability of the surgical and psychological outcomes.

Pain and mood disorders are intricately linked through shared neurobiological pathways, including central sensitization, inflammatory cytokines, and altered neurotransmission[12,13]. Frequently comorbid depression and pain occur within clinical settings, whereby patients show chronic levels of inflammation. The so-called neuroimmune mechanisms, linking the immune system and the CNS, are involved in the pathogenesis of both pain and depression in these individuals. Intense chronic inflammation can lead to a transition from transient adaptive normal responses to inflammation (enhanced pain sensitivity and neurovegetative symptoms, such as fatigue, reduced appetite, sleep disorders) to chronic conditions of depression and chronic pain that can remain even after the inflammation has diminished[14]. Chronic pain and mental health disorders bidirectionally influence each other, with overlapping brain regions and neurotransmitter pathways.

Surgical techniques that minimize nerve injury and postoperative pain may interrupt this cycle and help restore psychological balance. Indeed, minimizing nociceptive burden during surgery appears to reduce downstream psychiatric symptoms, a finding consistent with growing evidence in psychoneuroimmunology. From a trauma recovery perspective, the concept of a biopsychosocial model is indispensable. As articulated in trauma-informed care frameworks[15], recognizing the psychological impact of trauma is essential for comprehensive healing. Patients recovering from orthopedic trauma often report feelings of vulnerability, fear of reinjury, and functional dependency-all of which can be exacerbated by prolonged rehabilitation or poor surgical outcomes[16]. One in five orthopedic trauma patients suffer from psychological distress, with chronic pain appearing as frequent side effect of orthopedic trauma surgeries. As a frequent consequence, opioid or other analgesic therapy administration in orthopedic trauma patients can result in tolerance, dependence, and an increased risk of chronic opioid use, particularly in patients with depression[17].

Approaches that shorten recovery time, preserve nerve function, and reduce pain-as shown in Yang et al[7] may therefore mitigate these psychological risks. Moreover, the integration of early neurorehabilitation and psychological support has shown promise in improving both physical and mental health outcomes in trauma patients[18]. Rehabilitation strategies that incorporate cognitive-behavioral therapy, pain management, and functional goal setting may further enhance the benefits of minimally invasive surgery. Care for orthopedic trauma patients should include not only physical rehabilitation but also mental health support. Pre-injury and injury characteristics, such as upper vs lower extremity involvement, surgical technique and past psychiatric history, may influence the development of psychiatric pathology. The findings of Yang et al[7] should encourage orthopedic teams to assess psychological distress routinely and to tailor interventions accordingly. The use of validated tools such as the SAS/SDS, PSQI, and pain intensity ratings provide essential insights into a patient’s recovery trajectory[19,20].

CLINICAL CASE EXAMPLE

Patient profile

A 45-year-old woman, previously healthy and employed as a primary school teacher, was admitted after a motor vehicle accident resulting in a complex vertical shear pelvic fracture with lumbosacral plexus involvement. She reported severe lower-limb pain, numbness, and motor weakness, along with acute anxiety and insomnia triggered by fears of permanent disability and job loss.

Management

Given the location and complexity of the fracture, the orthopedic team opted for a transrectus lateral minimally invasive approach, aiming to decompress the entrapped nerves and stabilize the pelvic ring while minimizing tissue disruption. Psychiatric evaluation at admission confirmed moderate anxiety and depressive symptoms (SAS: 68; SDS: 66).

Outcome

Postoperatively, the patient experienced significantly reduced pain levels and faster motor function recovery compared to average open procedure outcomes. By the second week, her anxiety and depression scores had dropped considerably (SAS: 43; SDS: 45). She reported improved sleep, enhanced confidence in mobility, and resumed light physical therapy within three weeks. The integrated approach, which included psychological counseling and early rehabilitation, supported her emotional resilience and functional recovery.

This example demonstrates how minimally invasive orthopedic techniques, combined with multidisciplinary care, can positively influence both the physical and psychological recovery trajectory in complex trauma patients.

CONCLUSIONS

To address the psychological impact of pelvic fractures with lumbosacral plexus injury, particularly in the context of minimally invasive approaches like the lateral rectus technique, the integration of psychiatric assessments and multidisciplinary collaboration into orthopedic workflows is essential. As shown by Yang et al[7], minimally invasive techniques are associated with significant improvements in anxiety, depression, pain, and sleep quality-highlighting the need for a broader, patient-centered care model. Routine psychological screening using validated tools should be embedded into both preoperative and postoperative assessments to track patient well-being longitudinally[7,19,20]. These measures can be administered by trained nursing staff and interpreted with the support of mental health professionals, ensuring early identification of distress. Incorporating trauma-informed care and cognitive-behavioral interventions into postoperative rehabilitation, as supported by trauma recovery literature, enhances both physical and psychological recovery[15,18]. A collaborative model involving orthopedic surgeons, psychiatrists, psychologists, physiotherapists, and social workers can promote timely intervention, reduce chronic pain risk, and improve reintegration outcomes[19,20]. This multidisciplinary approach reflects a shift towards holistic trauma management and aligns with evolving standards in comprehensive orthopedic care. While studies like that of Yang et al[7] offer promising insights into the psychological benefits of minimally invasive techniques in pelvic fracture management, several potential confounding factors must be considered when interpreting these outcomes. Pre-existing mental health conditions, such as depression, anxiety disorders, or PTSD, are common in trauma populations and may independently influence postoperative psychological trajectories regardless of surgical approach[6,17,18]. Additionally, socioeconomic factors-including income level, education, employment status, and access to healthcare-can significantly affect a patient's capacity for recovery and engagement with postoperative care[16]. These elements may mediate or moderate psychological responses to surgery, potentially inflating or masking the true impact of surgical technique alone. Many retrospective studies lack detailed baseline psychiatric data and often do not control for these variables, which limits the ability to isolate the effects of the surgical intervention from broader psychosocial determinants. Future prospective studies should incorporate stratified sampling or multivariate analyses to adjust for these confounders and provide a more nuanced understanding of the interaction between surgical method and psychological recovery. Ongoing research should continue to integrate psychiatric metrics into orthopedic trials, validating not just structural outcomes but also the patient's mental health. A pressing need for collaboration between healthcare providers, mental health professionals, and social support systems is warranted to guarantee comprehensive mental care for patients with traumatic orthopedic injuries and pain[19,20]. Early recognition and intervention for psychiatric symptoms have the potential to enhance patient recovery and significantly improve overall outcomes[21-23]. A post-trauma collaborative team and psychological support groups may offer a major opportunity and a stimulating challenge to improve outcomes in this patient population. This approach aligns with evolving paradigms in patient-centered care and may ultimately improve long-term satisfaction and function.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Psychiatry

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade A, Grade A, Grade B, Grade B, Grade D

Novelty: Grade B, Grade B, Grade B, Grade B, Grade D

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B, Grade B, Grade B, Grade B, Grade B

Scientific Significance: Grade A, Grade A, Grade B, Grade B, Grade D

P-Reviewer: Colò G; Kamarehei M; Liu WC S-Editor: Li L L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang L