Published online Aug 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i8.105929

Revised: May 29, 2025

Accepted: June 24, 2025

Published online: August 19, 2025

Processing time: 100 Days and 2 Hours

Rabies is a zoonotic viral disease affecting the central nervous system, caused by the rabies virus, with a case-fatality rate of 100% once symptoms appear.

To analyze high-risk factors associated with mental disorders induced by rabies vaccination and to construct a risk prediction model to inform strategies for im

Patients who received rabies vaccinations at the Department of Infusion Yiwu Central Hospital between August 2024 and July 2025 were included, totaling 384 cases. Data were collected from medical records and included demographic characteristics (age, gender, occupation), lifestyle habits, and details regarding vaccine type, dosage, and injection site. The incidence of psychiatric disorders following vaccination was assessed using standardized anxiety and depression rating scales. Patients were categorized into two groups based on the presence or absence of anxiety and depression symptoms: The psychiatric disorder group and the non-psychiatric disorder group. Differences between the two groups were compared, and high-risk factors were identified using multivariate logistic re

Among the 384 patients who received rabies vaccinations, 36 cases (9.38%) were diagnosed with anxiety, 52 cases (13.54%) with depression, and 88 cases (22.92%) with either condition. Logistic regression analysis identified the following signi

In real-world settings, psychiatric disorders following rabies vaccination are relatively common and are associated with factors such as lower education level, higher exposure severity, vulnerable family status, and limited awa

Core Tip: Identifying risk factors for mental disorders induced by vaccination and constructing predictive models is essential for safeguarding the mental health of patients especially those receiving rabies vaccination. This study is based on real-world data and provides the first comprehensive and systematic analysis of the risk factors for mental disorders caused by rabies vaccination, and constructs a predictive model.

- Citation: Ding JY, Zhu JJ. Based on real-world data: Risk factors and prediction model for mental disorders induced by rabies vaccination. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(8): 105929

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i8/105929.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i8.105929

Rabies is a zoonotic viral disease of the central nervous system caused by the rabies virus, characterized by a case-fatality rate of 100% once clinical symptoms appear[1,2]. Patients typically present with severe agitation, hydrophobia, impaired consciousness, paralysis, and coma, ultimately succumbing to cardiac arrest, circulatory failure, or respiratory insufficiency[3]. Given the absence of specific therapeutic options, immediate wound care and rabies vaccination are essential for preventing disease onset[4]. With the increasing number of household pets and personal pet ownership in China, the risk and incidence of rabies exposure have risen significantly, resulting in higher vaccination rates[5]. However, many patients experience psychological distress such as anxiety, panic, and depression following rabies vaccination, often due to misconceptions about the disease or concerns regarding the vaccine’s efficacy[6]. These mental health issues can adversely affect patients’ daily functioning and work productivity. Although several studies have investigated the psychological condition of patients post-vaccination, most have been clinical trials or retrospective analyses that do not fully reflect the diversity and complexity of real-world settings. Real-world studies, conducted in routine clinical and everyday environments, offer more accurate insights into disease characteristics, treatment outcomes, and adverse reac

This observational study was conducted using real-world data. A total of 384 patients who received rabies vaccinations at the Department of Infusion our hospital between August 2024 and July 2025 were included. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Confirmed dog bite verified through clinical examination; (2) Age 18 years or older; (3) Presentation to the hospital within 24 hours of the bite; (4) Absence of infection at the wound site; (5) Eligibility for rabies vaccination; and (6) Provision of written informed consent after explanation of the study’s purpose and procedures. The exclusion criteria were: (1) Pre-existing psychiatric symptoms prior to the dog bite; (2) Presence of severe organ disease, hematological disorders, or immunodeficiency; (3) Impaired consciousness or cognitive dysfunction; (4) Contraindications to rabies vaccination or a history of related allergic reactions; (5) Critical condition preventing completion of the psychological assessment prior to vaccination; and (6) Pregnancy or breastfeeding. For data collection, snowball sampling was used to distribute electronic questionnaires. Initially, a small number of eligible patients were identified and invited to participate. These participants were provided with a quick response code to complete the survey and asked to re

Risk factor investigation: A self-designed questionnaire developed by the research team was used to collect detailed information based on patients’ medical records. Personal information included age, gender, occupation, lifestyle habits, and vaccine-related details such as type, dosage, and injection site.

Anxiety assessment: The generalized anxiety disorder scale[7] was used to assess recent anxiety symptoms. The scale consists of seven items, each scored from 0 to 3, with a maximum score of 21. A score of ≥ 5 indicates anxiety, with 5-9 classified as mild, 10-14 as moderate, and 15-21 as severe anxiety.

Depression assessment: The patient health questionnaire-9[8] was used to assess recent depressive symptoms. The scale comprises nine items, each scored from 0 to 3, with a total score of 27. A score of ≥ 5 indicates depression, with 5-9 repre

A self-developed survey on rabies prevention and control knowledge was used. The survey covered basic knowledge of rabies, wound management, and post-vaccination precautions. It included 14 items, each scored from 0 to 1, for a total score of 14. A score greater than 8 was considered indicative of sufficient awareness.

Snowball sampling was used to distribute electronic questionnaires. Participants accessed the survey by scanning a quick response code, and data were collected through an online platform. Before completing the survey, participants were informed of the study’s purpose and significance. Any questions were addressed via voice or video calls. A total of 400 questionnaires were distributed, of which 384 were valid, yielding a response rate of 96.0%.

All participants completed the mental health assessment and were categorized into two groups based on the presence or absence of anxiety and depression symptoms: The psychiatric disorder group and the non-psychiatric disorder group. These groups served as the modeling cohort for developing a risk prediction model for psychiatric disorders following rabies vaccination, based on identified risk factors. The model’s predictive accuracy was subsequently validated.

All data were analyzed using SPSS version 26.0. For normally distributed continuous variables, results were reported as mean ± SD and analyzed using independent sample t-tests. For non-normally distributed data, results were described using medians and interquartile ranges. Categorical variables were presented as percentages (%) and analyzed using χ2 tests. Risk factors were identified using multivariate logistic regression analysis. The predictive performance of the risk prediction model was evaluated using the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC). A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Among the 384 patients who received rabies vaccinations, 36 cases (9.38%) were diagnosed with anxiety, 52 cases (13.54%) with depression, and 88 cases (22.92%) with either condition. The remaining 296 patients (77.08%) constituted the non-psychiatric disorder group.

Compared to the non-psychiatric disorder group, patients in the psychiatric disorder group had higher rates of urban residence, education level of primary school or below, occupations as farmers or workers, and monthly per capita family income < 5000 Chinese yuan. They also had higher frequencies of exposure to the head and neck, grade III exposure, and more than one wound (P < 0.05). Additionally, they demonstrated lower rates of family completeness and lower awareness of rabies prevention and control knowledge (P < 0.05). No statistically significant differences were observed in other general characteristics between the two groups (P > 0.05). Detailed results are presented in Table 1.

| Variable | Psychiatric disorder group (n = 88) | Non-psychiatric disorder group (n = 296) | χ² value | P value |

| Gender | 0.006 | 0.937 | ||

| Male | 42 (48.84) | 146 (49.32) | ||

| Female | 44 (51.16) | 150 (50.68) | ||

| Age (years) | 0.470 | 0.791 | ||

| 18-35 | 31 (35.23) | 98 (33.11) | ||

| 36-60 | 42 (47.73) | 138 (46.62) | ||

| > 60 | 15 (17.05) | 60 (20.27) | ||

| Residence | 12.522 | 0.001 | ||

| Urban | 52 (59.09) | 112 (37.84) | ||

| Rural | 36 (40.91) | 184 (62.16) | ||

| Education level | 15.643 | < 0.001 | ||

| Primary school or below | 44 (50.00) | 86 (29.05) | ||

| Middle/high school | 28 (31.82) | 104 (35.14) | ||

| College or above | 16 (18.18) | 106 (35.81) | ||

| Occupation | 4.665 | 0.046 | ||

| Healthcare worker | 4 (4.55) | 34 (11.49) | ||

| Public institution | 24 (27.27) | 112 (37.84) | ||

| Corporate employee | 25 (28.41) | 108 (36.49) | ||

| Self-employed | 18 (20.45) | 27 (9.12) | ||

| Farmer/worker | 12 (13.64) | 13 (4.05) | ||

| Other | 5 (5.68) | 2 (0.68) | ||

| Monthly family income (Chinese yuan) | 11.553 | 0.003 | ||

| < 5000 | 28 (31.82) | 46 (15.54) | ||

| 5001-10000 | 42 (47.73) | 175 (59.12) | ||

| > 10000 | 18 (20.45) | 75 (25.34) | ||

| Family status | 6.638 | 0.024 | ||

| Complete | 25 (28.41) | 128 (43.24) | ||

| Living alone | 22 (25.00) | 65 (21.96) | ||

| Unmarried | 18 (20.45) | 48 (16.22) | ||

| Divorced/widowed | 23 (26.14) | 55 (18.58) | ||

| Exposure method | 0.026 | 0.987 | ||

| Bite | 35 (39.77) | 115 (38.85) | ||

| Scratch | 42 (47.73) | 143 (48.31) | ||

| Other | 11 (12.50) | 38 (12.84) | ||

| Exposure site | 20.303 | < 0.001 | ||

| Head/neck | 30 (34.09) | 45 (15.20) | ||

| Trunk | 35 (39.77) | 108 (36.49) | ||

| Limbs | 23 (26.14) | 143 (48.31) | ||

| Exposure degree | 22.646 | < 0.001 | ||

| Grade II | 62 (70.45) | 268 (90.54) | ||

| Grade III | 26 (29.55) | 28 (9.46) | ||

| Number of wounds | 8.416 | 0.004 | ||

| 1 wound | 65 (73.86) | 257 (86.82) | ||

| > 1 wound | 23 (26.14) | 39 (13.18) | ||

| Wound management | 0.317 | 0.853 | ||

| Self-managed | 31 (35.23) | 95 (32.09) | ||

| Unmanaged | 14 (15.91) | 51 (17.23) | ||

| Clinic managed | 43 (48.86) | 150 (50.68) | ||

| Time from injury to visit | 1.970 | 0.374 | ||

| < 6 hours | 25 (28.41) | 92 (31.08) | ||

| 6-12 hours | 36 (40.91) | 135 (45.61) | ||

| > 12 hours | 27 (30.68) | 69 (23.31) | ||

| Rabies immune globulin | 0.438 | 0.508 | ||

| Yes | 73 (82.95) | 254 (85.81) | ||

| No | 15 (17.05) | 42 (14.19) | ||

| Full vaccine course | 0.412 | 0.521 | ||

| Yes | 82 (93.18) | 283 (95.61) | ||

| No | 6 (6.82) | 13 (4.39) | ||

| Awareness of rabies prevention | 15.930 | < 0.001 | ||

| Aware | 45 (51.14) | 218 (73.65) | ||

| Unaware | 43 (48.86) | 78 (26.35) |

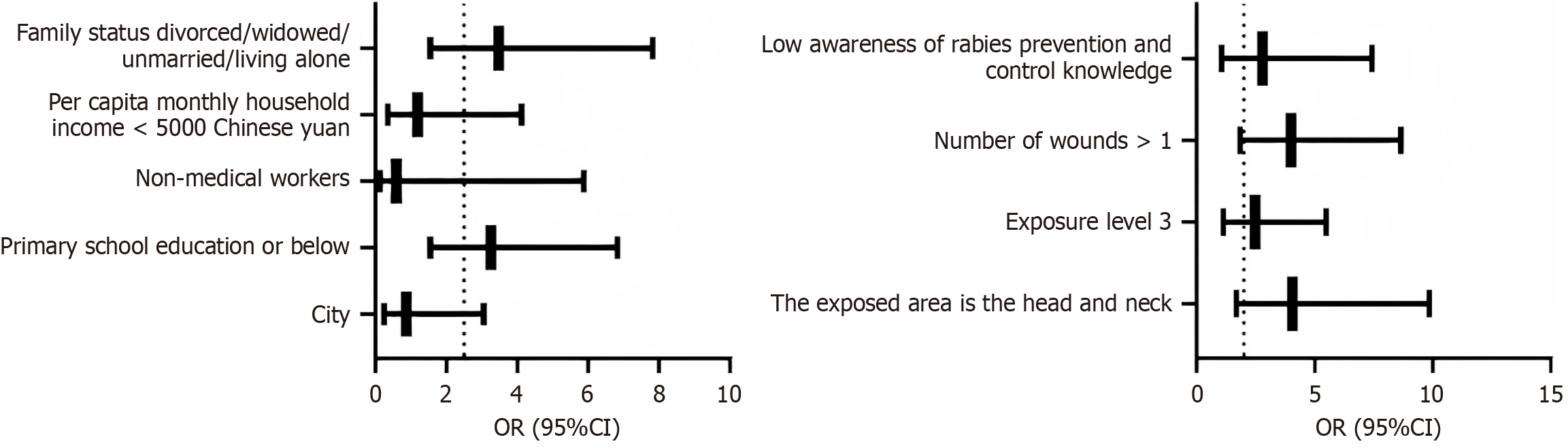

Variables with statistically significant differences in the univariate analysis were further analyzed using logistic re

| Factor | Coding |

| Residence | Urban = 1; Rural = 0 |

| Education level | Primary school or below = 1; Middle/high school = 0; College or above = 0 |

| Occupation | Farmer/worker = 1; All other categories = 0 |

| Monthly family income (Chinese yuan) | < 5000 = 1; 5001–10000 = 0; > 10000 = 0 |

| family status | Living alone/unmarried/divorced or widowed = 1; Complete = 0 |

| Exposure site | Head/neck = 1; Trunk = 0; Limbs = 0 |

| Exposure degree | Grade III = 1; Grade II = 0 |

| Number of wounds | > 1 wound = 1; 1 wound = 0 |

| Awareness of rabies prevention | Unaware = 1; Aware = 0 |

| Factor | β | SE | Wald | P value | OR | 95%CI |

| Urban | -0.139 | 0.128 | 1.179 | 0.468 | 0.870 | 0.248-3.052 |

| Primary school or below | 1.179 | 0.248 | 22.601 | 0.001 | 3.251 | 1.548-6.826 |

| Non-medical occupation | -0.151 | 0.276 | 1.873 | 0.522 | 0.588 | 0.140-5.876 |

| Monthly income < 5000 (Chinese yuan) | 0.171 | 0.108 | 2.507 | 0.260 | 1.187 | 0.342-4.120 |

| Divorced/widowed/unmarried/living alone | 1.247 | 0.360 | 11.999 | 0.001 | 3.480 | 1.548-7.825 |

| Head/neck exposure site | 1.402 | 0.271 | 26.764 | < 0.001 | 4.062 | 1.675-9.852 |

| Grade III exposure | 0.910 | 0.212 | 18.425 | < 0.001 | 2.483 | 1.125-5.482 |

| > 1 wound | 1.386 | 0.412 | 11.317 | < 0.001 | 3.999 | 1.848-8.652 |

| Low awareness of rabies prevention | 1.028 | 0.364 | 7.976 | 0.010 | 2.795 | 1.052-7.425 |

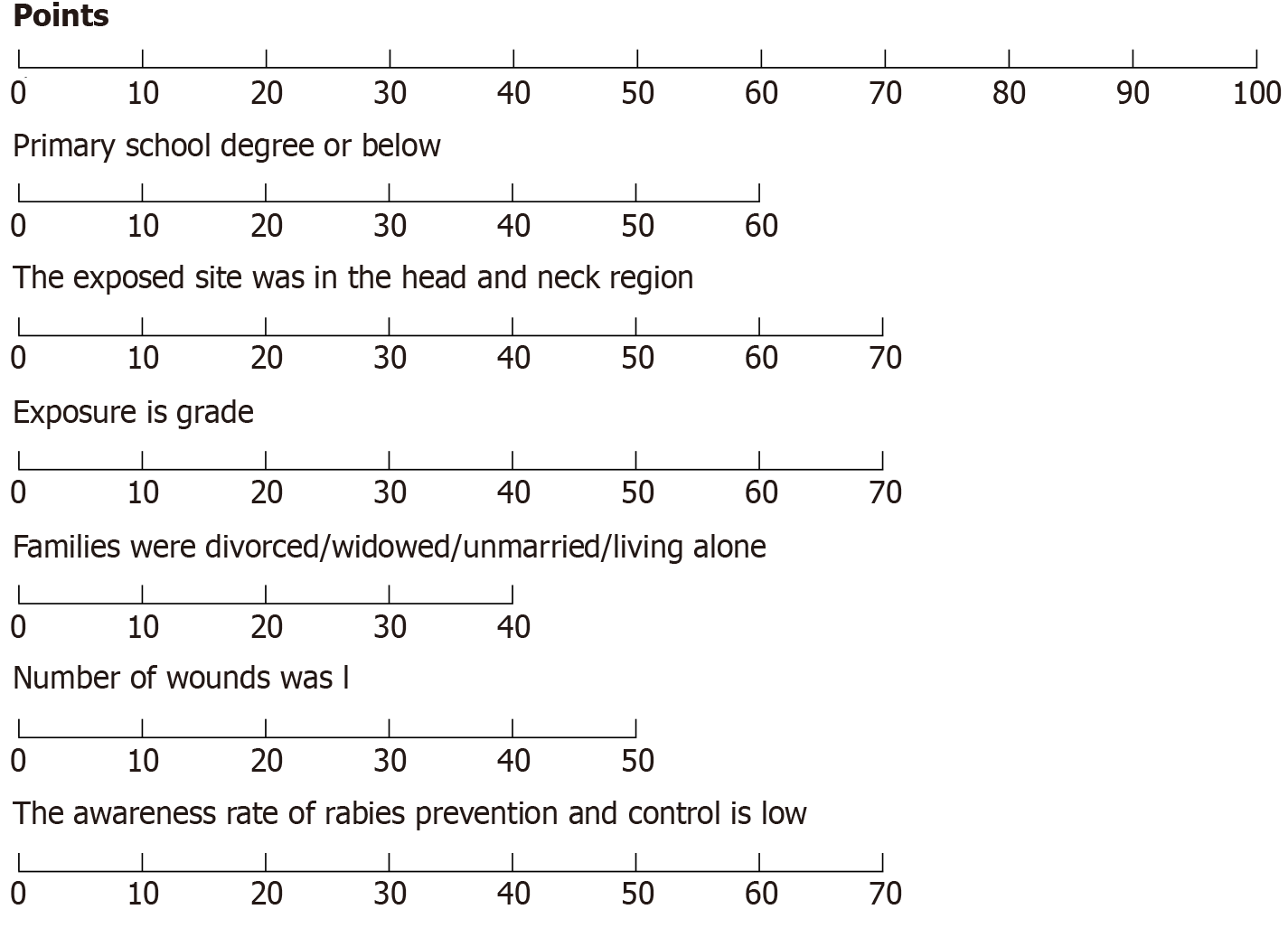

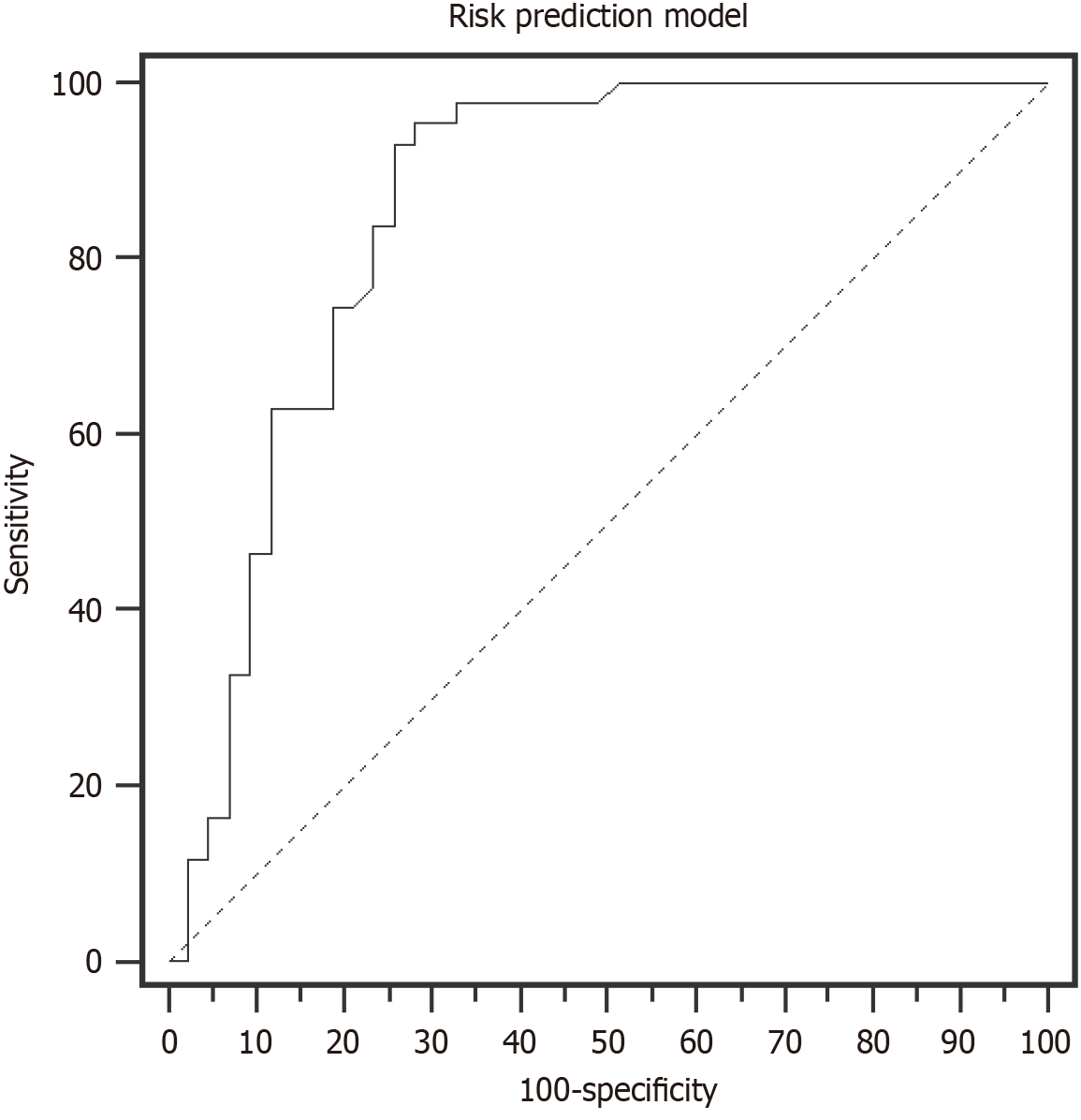

Based on the results of multivariate logistic regression analysis, a risk prediction model for rabies vaccination-induced psychiatric disorders was developed and presented as a nomogram (see Figure 2). The nomogram displays the relative contribution (score) of each risk factor to the total predicted probability. Model performance was evaluated using the ROC curve, yielding an AUC of 0.859, a specificity of 74.42%, and a sensitivity of 93.02%, as shown in Figure 3.

Dog bites are a common occurrence in China. Due to the high bacterial load in a dog’s mouth, muscle tissue exposed to the rabies virus can readily lead to infection if not promptly treated-resulting in death and posing significant challenges for disease prevention and control[9]. Rabies vaccination remains the only effective method for preventing and con

This study identified several risk factors for psychiatric disorders following rabies vaccination through logistic regression analysis. These included lower education level (primary school or below), exposure site on the head and neck, grade III exposure, family status of divorced/widowed/unmarried/Living alone, having more than one wound, and low awareness of rabies prevention and control (P < 0.05). These results suggest that patients are vulnerable to multiple psychosocial and clinical factors that may contribute to the development of psychiatric symptoms after rabies vaccination. Notably, neither the type nor the quantity of the vaccine was significantly associated with the occurrence of psychiatric disorders.

Limited knowledge of rabies presents a significant psychological burden. When exposed to rabies, many patients experience heightened anxiety due to fear of disease onset a potent psychological stressor that can trigger anxiety and depression. Patients with lower educational attainment are often less informed about rabies prevention and the effec

Family status also plays a crucial role in patients’ psychological well-being. A supportive family can offer emotional reassurance and encouragement, helping patients maintain a positive outlook toward rabies vaccination. Conversely, individuals living alone or grieving the loss of a loved one may experience loneliness and lack social support, which can adversely affect their mental health.

In cases of grade III exposure, referrals to higher-level medical facilities may delay timely treatment and aggravate the patient’s condition, increasing psychological stress and skepticism regarding vaccination. Many primary care institutions lack specialized staff for managing rabies exposure, which may reduce patient confidence in treatment outcomes and subsequent vaccination adherence[14]. Moreover, patients with severe injuries and multiple wounds often require rabies immune globulin injections, which are costly and involve complex wound care. The prolonged wound healing process and uncertainties about vaccine efficacy can lead to increased anxiety and depression[15].

Patients bitten on the head or neck may worry about visible scarring and perceive a higher risk of viral transmission due to the critical nature of these anatomical areas. Such concerns can undermine their trust in the vaccine’s effectiveness and heighten psychological distress. Therefore, identifying risk factors for psychiatric disorders induced by rabies vacci

This study developed a risk prediction model based on identified risk factors and validated it using the ROC curve. The AUC was 0.859, with a specificity of 74.42% and a sensitivity of 93.02%. These results demonstrate strong concor

In summary, by analyzing risk factors for psychiatric disorders induced by rabies vaccination in real-world settings and validating the predictive model through ROC analysis, this study provides a foundation for early identification of high-risk populations and offers meaningful insights for early clinical intervention. However, the study has several limitations. First, all data were collected from a single medical institution, which may limit the representativeness of the sample and reduce the generalizability of the findings. Second, the prediction model has not yet undergone external validation, potentially introducing bias into the results. Future studies should consider multi-center, large-scale trials and external validation to enhance the model’s robustness and provide a more reliable basis for clinical application.

In real-world settings, psychiatric disorders induced by rabies vaccination are relatively common and are influenced by factors such as educational background, exposure severity, family status, and awareness of rabies prevention and control. The development of a risk prediction model based on these factors can help identify high-risk groups at an early clinical stage and provide a reference for timely clinical intervention. However, due to limitations in the study design, all par

| 1. | Kumar A, Bhatt S, Kumar A, Rana T. Canine rabies: An epidemiological significance, pathogenesis, diagnosis, prevention, and public health issues. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2023;97:101992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Arsuaga M, de Miguel Buckley R, Díaz-Menéndez M. Rabies: Epidemiological update and pre- and post-exposure management. Med Clin (Barc). 2024;162:542-548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Gibbons K, Dvoracek K. Rabies postexposure prophylaxis: What the U.S. emergency medicine provider needs to know. Acad Emerg Med. 2023;30:1144-1149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kaye AD, Perilloux DM, Field E, Orvin CA, Zaheri SC, Upshaw WC, Behara R, Parker-Actlis TQ, Kaye AM, Ahmadzadeh S, Shekoohi S, Varrassi G. Rabies Vaccine for Prophylaxis and Treatment of Rabies: A Narrative Review. Cureus. 2024;16:e62429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ghassemi S, Pourbadie HG, Prehaud C, Lafon M, Sayyah M. Role of the glycoprotein thorns in anxious effects of rabies virus: Evidence from an animal study. Brain Res Bull. 2022;185:107-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bodner E, Bergman YS, Ben-David B, Palgi Y. Vaccination anxiety when vaccinations are available: The role of existential concerns. Stress Health. 2022;38:111-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lee C, Round JM, Hanlon JG, Hyshka E, Dyck JRB, Eurich DT. Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-Item (GAD-7) Scores in Medically Authorized Cannabis Patients-Ontario and Alberta, Canada. Can J Psychiatry. 2022;67:470-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Negeri ZF, Levis B, Sun Y, He C, Krishnan A, Wu Y, Bhandari PM, Neupane D, Brehaut E, Benedetti A, Thombs BD; Depression Screening Data (DEPRESSD) PHQ Group. Accuracy of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 for screening to detect major depression: updated systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. BMJ. 2021;375:n2183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 36.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Whitehouse ER, Mandra A, Bonwitt J, Beasley EA, Taliano J, Rao AK. Human rabies despite post-exposure prophylaxis: a systematic review of fatal breakthrough infections after zoonotic exposures. Lancet Infect Dis. 2023;23:e167-e174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ahmad N, Nawi AM, Jamhari MN, Nurumal SR, Mansor J, Zamzuri M'IA, Yin TL, Hassan MR. Post-Exposure Prophylactic Vaccination against Rabies: A Systematic Review. Iran J Public Health. 2022;51:967-977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Warmerdam AMT, Luppino FS, Visser LG. The occurrence and extent of anxiety and distress among Dutch travellers after encountering an animal associated injury. Trop Dis Travel Med Vaccines. 2023;9:11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Westgarth C, Provazza S, Nicholas J, Gray V. Review of psychological effects of dog bites in children. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2024;8:e000922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ubeyratne K, Srikitjakarn L, Pfeiffer D, Kong F, Sunil-Chandra N, Chaisowwong W, Hemwan P. A Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices (KAP) survey on canine rabies prevention and control in four rural areas of Sri Lanka. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2021;68:3366-3380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zhu M, Mu D, Chen Q, Chen N, Zhang Y, Yin W, Li Y, Chen Y, Deng Y, Tang X. Awareness Towards Rabies and Exposure Rate and Treatment of Dog-Bite Injuries Among Rural Residents - Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, China, 2021. China CDC Wkly. 2021;3:1139-1142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lodha L, Manoor Ananda A, Mani RS. Rabies control in high-burden countries: role of universal pre-exposure immunization. Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia. 2023;19:100258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |