Published online Aug 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i8.104221

Revised: April 11, 2025

Accepted: June 16, 2025

Published online: August 19, 2025

Processing time: 238 Days and 4.2 Hours

Bipolar disorder (BD), marked by recurring manic and depressive episodes, often coexists with anxiety disorder (AD), which increases treatment complexity and morbidity. Although quetiapine, an atypical antipsychotic, has demonstrated efficacy in treating BD and AD, further investigation is needed regarding its effectiveness and safety in patients with AD at high-risk factors for BD.

To explore the application and efficacy of quetiapine in combination therapy for patients with AD at high-risk factors for BD.

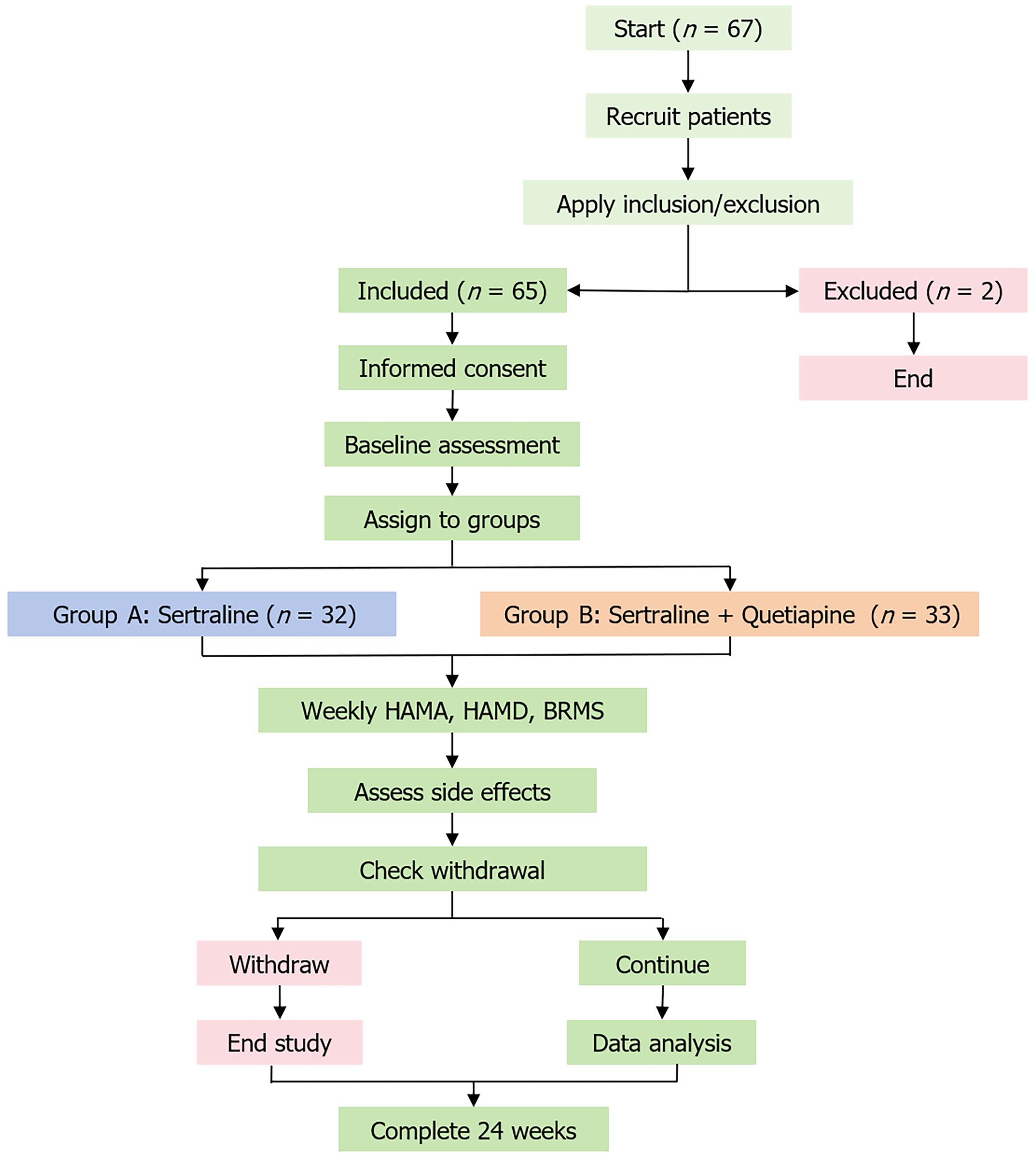

This study included 67 patients, with two excluded, leaving 65 divided into Group A (sertraline treatment) and Group B (combination treatment). All patients received sertraline, with Group B additionally receiving quetiapine. Efficacy was assessed using the Hamilton anxiety scale (HAMA), Hamilton depression scale (HAMD), and Bech-Rafaelsen Mania sale (BRMS) throughout the treatment period. Side effects and physiological indicators were also monitored.

No significant baseline differences existed between the two groups at treatment onset. Over the treatment course, Group B exhibited significantly lower HAMA scores than Group A at the end of weeks 1 and 24. HAMD scores gradually decreased over time, with Group B consistently showing lower scores than Group A. BRMS scores decreased significantly from baseline by week 8. In Group A, 27.27% of patients received zolpidem treatment compared to 10.53% in Group B, which was a significant difference. Incidence of adverse reactions did not differ significantly between groups at treatment onset, but most patients experienced relief from adverse reactions within 4 weeks.

Combination of quetiapine and sertraline can more rapidly alleviate anxiety and depressive symptoms in patients with AD at high-risk factors for BD, improving treatment outcomes.

Core Tip: This study evaluated the efficacy and safety of quetiapine combined with sertraline in patients with anxiety disorder (AD) and high-risk factors for bipolar disorder (BD). In a 24-week randomized trial involving 65 patients, those receiving combination therapy (Group B) showed significantly lower Hamilton anxiety scale scores than those on sertraline monotherapy (Group A) at weeks 1 and 24. Group B also demonstrated faster and sustained reductions in Hamilton depression scale and Bech-Rafaelsen Mania sale scores. Group B required less adjunctive zolpidem for insomnia, with no significant difference in adverse reactions between the groups. These findings support the use of quetiapine as an adjunctive treatment for managing complex AD at high-risk factors for BD, offering a safer and more effective strategy for high-risk patients.

- Citation: Lei LL, Ge CJ, Wang H, Fang Y, Zeng L, Wang SL, Qian MC. Application and efficacy of quetiapine in patients with high-risk factors for bipolar disorder: A randomized controlled trial. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(8): 104221

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i8/104221.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i8.104221

Bipolar disorder (BD) affects approximately 2.8% of adults globally, and is characterized by complex etiology involving biochemical imbalances, seasonal changes, and stressful life events. Patients with BD frequently experience rapid mood swings and emotional dysregulation, complicating the treatment and management of the illness, while greatly increasing its social and economic burden. BD not only affects mood regulation but is often accompanied by other mental disorders, with anxiety disorder (AD) being one of the most common comorbidities[1]. AD is a mental disorder characterized by persistent and excessive anxiety and fear. Research indicates that up to 50% of BD patients also have comorbid AD, and often display more complex clinical symptoms[2]. Importantly, compared to patients who have BD alone, those with comorbid AD are more likely to experience fast cycling, greater emotional instability, and a heightened risk of suicide[3]. Therefore, how to effectively treat BD patients with comorbid AD has become an important area of research in psychiatry[4].

Current BD treatment focuses on mood stabilization and symptom control, with physicians actively exploring patient psychological states to implement effective interventions[5]. The main medications used for treating BD are mood stabilizers, such as lithium and valproate. However, monotherapies of this kind often take effect slowly, are less effective at stabilizing the condition, and have numerous side effects with long-term use, limiting their clinical application[6]. Common anxiety medications like sertraline carry the risk of triggering mood swings and increasing mania risk when used alone in BD patients[7]. Therefore, finding a drug combination or single medication that can effectively address both BD and AD has become a key therapeutic challenge.

Quetiapine, an atypical antipsychotic, has demonstrated efficacy in treating both BD and AD in recent years[8]. Originally developed for schizophrenia treatment, quetiapine functions through dual antagonism of serotonin (5-HT2A) and dopamine (D2) receptors, contributing to its anxiolytic and mood-stabilizing properties[9]. Studies have shown that quetiapine effectively improves depressive symptoms in BD patients, and reduces the occurrence of anxiety during treatment. Quetiapine also has better tolerability, with fewer extrapyramidal side effects than other antipsychotics and is thus more suitable for long-term treatment. Due to its anxiolytic properties, quetiapine is an important therapeutic option for BD patients with comorbid AD[10]. Currently, although quetiapine does show individual efficacy in treating both BD and AD, research on its efficacy in patients with AD at high-risk factors for BD is still scarce[11]. To understand what kind of therapeutic effect quetiapine can have in this patient group, researchers have begun to explore its use combined with other drugs. The current study evaluated the effects, efficacy and safety of quetiapine combined with commonly used anxiolytic sertraline in patients with AD at high-risk factors for BD, to provide new clinical treatment for these patients[11].

Inclusion criteria: (1) Patients diagnosed with social AD, panic disorder, or generalized AD (GAD) according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition; (2) Patients with BD with at least one of the following high-risk factors: Age < 18 years, family history of BD, significant negative thoughts or behaviors, or subthreshold manic symptoms [score between 1 and 5 on the Bech-Rafaelsen Mania scale (BRMS)]; (3) Individuals of Han ethnicity aged 18-60 years; (4) Total score of ≥ 14 on the Hamilton anxiety scale (HAMA) and < 17 on the Hamilton depression scale (HAMD); (5) No medication use for > 2 weeks prior to registration; and (6) Approval from the hospital ethics committee, voluntary participation in the study, and signed written informed consent.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Patients with a history of substance, alcohol, or other psychoactive substance abuse; (2) Patients with significant abnormalities found in laboratory and auxiliary examinations; (3) Patients unable to cooperate or complete examinations due to consciousness, vision, hearing, language expression, or comprehension disorders; (4) Patients with severe physical illnesses such as heart, lung, liver, kidney dysfunction, shock, malignant tumors, and autoimmune diseases; (5) Patients taking glucocorticoids, immunomodulators, antipyretics, and analgesics; and (6) Women who were pregnant or breastfeeding.

Withdrawal criteria: (1) Patients who voluntarily requested to withdraw their consent; (2) Nonadherence to research protocols during the study; (3) Presence of psychiatric symptoms such as agitation or delusions; (4) Disturbances of consciousness; or (6) Pregnancy.

Between January 2021 and December 2022, 67 patients were admitted to our hospital, with two withdrawing from treatment for various reasons. The remaining 65 patients were divided into Group A (sertraline treatment group) with 32 cases and Group B (combination treatment group) with 33 cases. In Group A, there were 13 males and 19 females with an average age of 44.31 ± 11.7 years. Among the 32 patients, two were unmarried and two were divorced. The average disease course was 64.03 ± 62.92 months, and the average duration of education was 10.03 ± 3.54 years. All patients in Group A were diagnosed with GAD. In Group B, there were 11 males and 22 females with an average age of 43.00 ± 13.76 years; seven were unmarried and two were divorced. The average disease course was 65.24 ± 66.613 months, and the duration of education was 9.48 ± 3.801 years. In Group B, 32 patients were diagnosed with GAD and panic disorder. The general data of the two groups were not significantly different (P > 0.05).

At the commencement of the study, participants in both groups were administered sertraline, with the dose incrementally adjusted according to individual response. In addition to sertraline, Group B also received quetiapine as part of the treatment regimen. For patients experiencing severe insomnia at night, a bedtime dose of 10 mg zolpidem tartrate was recommended. To evaluate the therapeutic effects, participants were assessed using HAMA, HAMD and BRMS at the beginning of the experiment (baseline) and at the end of weeks 1, 2, 4, 8, 16 and 24. The treatment emergent symptom scale was utilized to evaluate potential side effects of the medication. Complete blood count, hepatic and renal functions, thyroid function, and electrocardiograms were monitored at baseline and at the end of weeks 2, 4, 8, 16 and 24 (Figure 1).

The random number generation for allocating participants to Groups A and B was conducted using a computer-generated random number sequence. This method ensured that each participant had an equal chance of being assigned to either group, thereby maintaining the integrity of the randomization process.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 23.0. Measurement data were analyzed using independent samples t tests, with a significance level of P < 0.05. All comparisons were conducted between the two groups.

At the onset of treatment, there were no significant differences in baseline scores between the two groups (P > 0.05). However, as the treatment progressed, HAMA scores gradually decreased. At the end of weeks 1 and 24, scores in Group B were significantly lower than those in Group A (P < 0.05). However, the score differences between the two groups at weeks 2, 4, 8 and 16 did not reach significance (P > 0.05) (Table 1). Line graphs have been added to illustrate the trajectories of HAMA scores for both groups over the 24-week study period (Supplementary Figure 1).

| Baseline | 1 week | 2 weeks | 4 weeks | 8 weeks | 16 weeks | 24 weeks | |

| A group | 22.31 ± 2.49 | 16.31 ± 3.34 | 11.47 ± 3.44 | 7.84 ± 3.85 | 6.00 ± 3.47 | 4.94 ± 2.66 | 5.44 ± 3.13 |

| B group | 22.18 ± 2.87 | 13.09 ± 3.15 | 9.79 ± 4.34 | 6.15 ± 4.24 | 4.76 ± 3.90 | 3.97 ± 3.10 | 3.79 ± 3.36 |

| t value | 0.196 | 4.007 | 1.729 | 1.683 | 1.355 | 1.349 | 2.046 |

| P value | 0.845 | < 0.001 | 0.089 | 0.097 | 0.180 | 0.182 | 0.045 |

At the beginning of treatment, there were no significant differences in HAMD scores between the two groups (P > 0.05). As the treatment progressed, the HAMD scores showed a gradual decline. Group B consistently had lower scores than Group A throughout the treatment period, and this difference was significant (P < 0.05). However, at weeks 4, 8, 16 and 24 of the treatment, the score differences between the two groups were not significant (P > 0.05) (Table 2).

| Baseline | 1 week | 2 weeks | 4 weeks | 8 weeks | 16 weeks | 24 weeks | |

| A group | 12.97 ± 2.50 | 8.44 ± 2.79 | 5.44 ± 3.48 | 4.28 ± 2.67 | 3.41 ± 2.09 | 2.91 ± 1.61 | 2.81 ± 1.66 |

| B group | 13.33 ± 2.29 | 6.64 ± 2.00 | 3.42 ± 2.68 | 3.45 ± 2.86 | 2.79 ± 2.22 | 2.48 ± 1.79 | 2.45 ± 1.89 |

| t value | -0.614 | 2.998 | 2.617 | 1.204 | 1.155 | 0.997 | 0.812 |

| P value | 0.541 | 0.004 | 0.011 | 0.233 | 0.252 | 0.323 | 0.420 |

From baseline to the end of week 24 follow-up, the changes in scores between the two groups did not show significant differences (P > 0.05). However, both groups exhibited a significant reduction in scores compared to baseline levels by the end of the treatment (week 8) (P < 0.05), indicating a positive impact of the treatment on symptom improvement in patients (Table 3).

| Baseline | 1 week | 2 weeks | 4 weeks | 8 weeks | 16 weeks | 24 weeks | |

| A group | 3.59 ± 2.86 | 1.09 ± 1.69 | 0.28 ± 0.58 | 0.16 ± 0.45 | 0.16 ± 0.57 | 0.16 ± 0.44 | 0.31 ± 0.93 |

| B group | 3.15 ± 2.86 | 1.18 ± 1.55 | 0.33 ± 0.85 | 0.15 ± 0.44 | 0.06 ± 0.24 | 0.03 ± 0.17 | 0.15 ± 0.57 |

| t value | 0.623 | -0.219 | -0.287 | 0.043 | 0.880 | 1.503 | 0.845 |

| P value | 0.536 | 0.827 | 0.775 | 0.966 | 0.382 | 0.138 | 0.401 |

In this study, 27.27% of the patients in Group A received zolpidem treatment, compared to 10.53% in Group B. This difference between the two groups was significant (P < 0.05), indicating a marked disparity in the utilization of zolpidem between the groups.

During the first week of treatment, four adverse reactions were recorded in Group B, primarily manifesting as gastrointestinal symptoms and headaches. Upon entering the second week of treatment, three patients in Group A reported adverse reactions, with symptoms including gastrointestinal discomfort and fatigue. Although adverse reactions were reported in both groups, there was no significant difference in the incidence of adverse reactions between the two groups (P > 0.05). However, it is noteworthy that within 4 weeks after treatment, 85.71% of the patients experienced alleviation of adverse reactions. These data suggest that despite the occurrence of some adverse reactions during the treatment process, the majority of patients were able to recover in the short term.

We monitored complete blood counts, hepatic and renal functions, thyroid function, and electrocardiograms at baseline and at the end of weeks 2, 4, 8, 16 and 24 (Supplementary Table 1). All parameters remained within normal clinical ranges throughout the study, and no significant differences were observed between the two groups at any time point (P > 0.05).

ADs are typically marked by excessive tension, worry, or fear. Research indicates that individuals with ADs are nine times more likely to develop BD than the general population[12]. BD, also known as manic-depressive illness, is a prevalent and disabling mental health condition marked by emotional instability and alternating episodes of mania and depression, sometimes exhibiting mixed features[13]. It is widely acknowledged that diagnosis of BD is often delayed, with some patients waiting as long as a decade for a correct diagnosis. BD frequently co-occurs with other conditions, including ADs, eating disorders, personality disorders, and substance use disorders[14]. In adolescent patients, anxiety symptoms are considered a risk factor for the development of BD, with some individuals diagnosed with ADs during their teenage years. Anxiety symptoms are also common in patients with BD, with research by Inoue et al[15] indicating that > 50% of patients with BD will experience anxiety symptoms at some point in their lives.

The significantly lower HAMA and HAMD scores in Group B (combination therapy) suggest a synergistic effect of quetiapine and sertraline. The anxiolytic and mood-stabilizing properties of quetiapine, attributed to its dual antagonism of 5-HT2A and D2 receptors, likely contributed to the observed benefits. This aligns with previous research indicating the efficacy of quetiapine in managing anxiety and depressive symptoms in BD patients[16]. Our findings are consistent with studies that reported improved mood disorders in adolescents using a similar combination therapy. However, our study extends these results by focusing on a specific high-risk population, providing further evidence for the utility of quetiapine in preventing treatment destabilization in patients prone to BD.

Although the comorbidity of BD and AD is common, the underlying causes are not fully understood, and research in this area is limited[17]. Current evidence suggests that this comorbidity may be associated with neurobiological, genetic, traumatic, and other sociopsychological factors[16]. Some researchers propose that AD may be a component of BD, a significant risk factor for its onset, or even a prodromal symptom[18]. The occurrence of ADs in young people may predict a genetic predisposition to BD[19]. However, further research is needed to establish these specific associations.

Although studies[20] have shown that patients with comorbid BD and AD do not exhibit a more severe course or frequency of episodes, some research indicates that patients with comorbidity may have an earlier age of onset, increased cognitive impairments, prolonged disease duration, higher chances of disease relapse, increased suicide risk, and even shorter lifespans[21]. In a 2-year follow-up, patients with comorbidity had higher depression scores at various time points and lower remission rates[22]. These risks and characteristics pose challenges for treatment, making the exploration of appropriate therapeutic strategies at the level of comorbidity of significant clinical value[23].

The presence of comorbidity complicates the diagnosis of the disease and increases the difficulty of confirmation. In patients with comorbid conditions, ADs often appear earlier than BD, which may lead to the misdiagnosis of BD as AD and inappropriate treatment, such as the prescription of antidepressants. Previous research has shown that antidepressants, commonly used as a first-line treatment for anxiety, can trigger manic episodes and are associated with irritability, rapid cycling, treatment resistance, and suicidal behavior[24]. This delay in appropriate treatment may result in inadequate initial management and lead to future relapses and functional impairment[25].

The efficacy of antidepressants has been well established, and they are recommended for the treatment of various ADs[26]. In some cases, acute depressive and anxiety episodes can be controlled through combined treatment with lithium, valproic acid, or atypical antipsychotic drugs. This study primarily focused on patients with AD at high risk for BD and observed the effects of sertraline alone and in combination with quetiapine. Sertraline, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, is the first-choice drug in the clinical treatment of ADs due to its single pharmacological mechanism of action and lack of addictive potential[27]. Lithium is a classic mood stabilizer that can reduce the sensitivity of serotonin receptors and increase the release of serotonin, thereby improving physiological functions and exerting both antidepressant and anxiolytic effects. However, some studies have shown that individuals with BD and anxiety symptoms may not respond well to lithium. Atypical antipsychotic drugs mainly work by blocking dopamine receptors and also affect α1-adrenergic receptors, histamine receptors, and γ-aminobutyric acid receptors, serving as adjunctive treatments for GAD, panic disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Quetiapine, an atypical antipsychotic drug, was used in the study group and compared with the sertraline-only group.

The results of this study indicate that the combined use of sertraline and quetiapine significantly reduced HAMA and HAMD scores compared to the use of sertraline alone, suggesting a potential synergistic effect in reducing symptoms of anxiety and depression[28]. The anxiolytic effects of quetiapine seemed to be sustained over time, with Group A having higher HAMA scores than Group B at the end of week 24. These findings are consistent with a study by Blasco-Fontecilla et al[29], who also reported that combined treatment with sertraline and quetiapine significantly improved mood disorders, depression, and anxiety symptoms in patients after stroke.

The Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for BD (STEP-BD) study found that over half of the patients had comorbid anxiety, beginning at an early stage[29]. In this study, patients had at least one high-risk factor for BD. However, the overall older age of the patients, longer disease history, and absence of manic or hypomanic symptoms lasting > 4 days in the longer disease history suggest that the risk of developing BD in patients with a longer history of AD may be lower[30]. The study followed these patients for 24 weeks, and neither group exhibited significant manic symptoms.

The findings of this study have significant clinical implications, particularly in alignment with the STEP-BD recommendations for adjunctive antipsychotics in high-risk cases. The combination of sertraline and quetiapine not only demonstrated faster and more sustained improvements in anxiety and depressive symptoms but also required less adjunctive zolpidem for insomnia. This supports the use of adjunctive antipsychotics in managing complex comorbid conditions, especially in patients with high-risk factors for BD. Our results provide further evidence for the efficacy and safety of this approach, offering clinicians a valuable treatment option for patients who may not respond adequately to traditional monotherapies.

Despite the promising results, our study had some limitations. The sample size was small, and the follow-up period was short, which may affect the generalization of the findings. Additionally, the lack of a placebo control limits our ability to fully attribute observed effects to the combination therapy. Future studies should consider larger sample sizes, longer follow-up periods, and the inclusion of a placebo group to validate these findings. Additionally, exploring the long-term effects of quetiapine in this population could provide valuable insights into its role in preventing the onset of BD.

In summary, combination therapy with quetiapine for patients with AD and high-risk factors for BD can more rapidly alleviate symptoms of anxiety and depression, thereby improving treatment outcomes. However, this study did not find any evidence to suggest that the combined use of quetiapine has an impact on the risk of developing BD in patients with a long history of AD. It is important to note that this study had some limitations, including a small sample size, longer patient disease history, use of different medications, and a short follow-up period. These limitations may affect the conclusions of the study, and future research should address these limitations with further investigation.

| 1. | Nierenberg AA, Agustini B, Köhler-Forsberg O, Cusin C, Katz D, Sylvia LG, Peters A, Berk M. Diagnosis and Treatment of Bipolar Disorder: A Review. JAMA. 2023;330:1370-1380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Buckley V, Young AH, Smith P. Child and adolescent anxiety as a risk factor for bipolar disorder: A systematic review of longitudinal studies. Bipolar Disord. 2023;25:278-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sala R, Axelson DA, Castro-Fornieles J, Goldstein TR, Ha W, Liao F, Gill MK, Iyengar S, Strober MA, Goldstein BI, Yen S, Hower H, Hunt J, Ryan ND, Dickstein D, Keller MB, Birmaher B. Comorbid anxiety in children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders: prevalence and clinical correlates. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:1344-1350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Altinbaş K. Treatment of Comorbid Psychiatric Disorders with Bipolar Disorder. Noro Psikiyatr Ars. 2021;58:S41-S46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | McIntyre RS, Alda M, Baldessarini RJ, Bauer M, Berk M, Correll CU, Fagiolini A, Fountoulakis K, Frye MA, Grunze H, Kessing LV, Miklowitz DJ, Parker G, Post RM, Swann AC, Suppes T, Vieta E, Young A, Maj M. The clinical characterization of the adult patient with bipolar disorder aimed at personalization of management. World Psychiatry. 2022;21:364-387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 30.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Marangoni C, Faedda GL, Baldessarini RJ. Clinical and Environmental Risk Factors for Bipolar Disorder: Review of Prospective Studies. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2018;26:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fornaro M, Anastasia A, Novello S, Fusco A, Solmi M, Monaco F, Veronese N, De Berardis D, de Bartolomeis A. Incidence, prevalence and clinical correlates of antidepressant-emergent mania in bipolar depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20:195-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Smith KA, Cipriani A. Lithium and suicide in mood disorders: Updated meta-review of the scientific literature. Bipolar Disord. 2017;19:575-586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | González-Pinto A, Galán J, Martín-Carrasco M, Ballesteros J, Maurino J, Vieta E. Anxiety as a marker of severity in acute mania. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;126:351-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Xuan R, Li X, Qiao Y, Guo Q, Liu X, Deng W, Hu Q, Wang K, Zhang L. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for bipolar disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290:113116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Suttajit S, Srisurapanont M, Maneeton N, Maneeton B. Quetiapine for acute bipolar depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2014;8:827-838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Meier SM, Uher R, Mors O, Dalsgaard S, Munk-Olsen T, Laursen TM, Mattheisen M, Nordentoft M, Mortensen PB, Pavlova B. Specific anxiety disorders and subsequent risk for bipolar disorder: a nationwide study. World Psychiatry. 2016;15:187-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hafeman DM, Merranko J, Axelson D, Goldstein BI, Goldstein T, Monk K, Hickey MB, Sakolsky D, Diler R, Iyengar S, Brent D, Kupfer D, Birmaher B. Toward the Definition of a Bipolar Prodrome: Dimensional Predictors of Bipolar Spectrum Disorders in At-Risk Youths. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:695-704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Cohen JN, Taylor Dryman M, Morrison AS, Gilbert KE, Heimberg RG, Gruber J. Positive and Negative Affect as Links Between Social Anxiety and Depression: Predicting Concurrent and Prospective Mood Symptoms in Unipolar and Bipolar Mood Disorders. Behav Ther. 2017;48:820-833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Inoue T, Kimura T, Inagaki Y, Shirakawa O. Prevalence of Comorbid Anxiety Disorders and Their Associated Factors in Patients with Bipolar Disorder or Major Depressive Disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2020;16:1695-1704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lin CY, Chiang CH, Tseng MM, Tam KW, Loh EW. Effects of quetiapine on sleep: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2023;67:22-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Çörekçioğlu S, Cesur E, Devrim Balaban Ö. Relationship between impulsivity, comorbid anxiety and neurocognitive functions in bipolar disorder. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2021;25:62-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kadriu B, Deng ZD, Kraus C, Johnston JN, Fijtman A, Henter ID, Kasper S, Zarate CA Jr. The impact of body mass index on the clinical features of bipolar disorder: A STEP-BD study. Bipolar Disord. 2024;26:160-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Spoorthy MS, Chakrabarti S, Grover S. Comorbidity of bipolar and anxiety disorders: An overview of trends in research. World J Psychiatry. 2019;9:7-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Titone MK, Freed RD, O'Garro-Moore JK, Gepty A, Ng TH, Stange JP, Abramson LY, Alloy LB. The role of lifetime anxiety history in the course of bipolar spectrum disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2018;264:202-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Su J, Zhang J, Zhu H, Lu J. Association of anxiety disorder, depression, and bipolar disorder with autoimmune thyroiditis: A bidirectional two-sample mendelian randomized study. J Affect Disord. 2025;368:720-726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | McIntyre RS, Calabrese JR. Bipolar depression: the clinical characteristics and unmet needs of a complex disorder. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35:1993-2005. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Mucci F, Toni C, Favaretto E, Vannucchi G, Marazziti D, Perugi G. Obsessive-compulsive Disorder with Comorbid Bipolar Disorders: Clinical Features and Treatment Implications. Curr Med Chem. 2018;25:5722-5730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Gottlieb N, Young AH. Antidepressants and Bipolar Disorder: The Plot Thickens. Am J Psychiatry. 2024;181:575-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Altamura AC, Buoli M, Caldiroli A, Caron L, Cumerlato Melter C, Dobrea C, Cigliobianco M, Zanelli Quarantini F. Misdiagnosis, duration of untreated illness (DUI) and outcome in bipolar patients with psychotic symptoms: A naturalistic study. J Affect Disord. 2015;182:70-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Poulin TG, Jaworska N, Stelfox HT, Fiest KM, Moss SJ. Clinical practice guideline recommendations for diagnosis and management of anxiety and depression in hospitalized adults with delirium: a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2023;12:174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Elliott SJ, Marshall D, Morley K, Uphoff E, Kumar M, Meader N. Behavioural and cognitive behavioural therapy for obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) in individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;9:CD013173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Hong JSW, Atkinson LZ, Al-Juffali N, Awad A, Geddes JR, Tunbridge EM, Harrison PJ, Cipriani A. Gabapentin and pregabalin in bipolar disorder, anxiety states, and insomnia: Systematic review, meta-analysis, and rationale. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27:1339-1349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Blasco-Fontecilla H, Bragado Jiménez MD, García Santos LM, Barjau Romero JM. Delusional disorder with delusions of parasitosis and jealousy after stroke: treatment with quetiapine and sertraline. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;25:615-617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Melhuish Beaupre LM, Tiwari AK, Gonçalves VF, Lisoway AJ, Harripaul RS, Müller DJ, Zai CC, Kennedy JL. Antidepressant-Associated Mania in Bipolar Disorder: A Review and Meta-analysis of Potential Clinical and Genetic Risk Factors. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2020;40:180-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |