Published online Aug 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i8.103302

Revised: March 21, 2025

Accepted: June 12, 2025

Published online: August 19, 2025

Processing time: 171 Days and 2.4 Hours

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is an increasingly common treatment for older patients with hip osteoarthritis. Psychological stress is common before THA, although its clinical effects on selected parameters such as joint function, quality of life, and postoperative complications remain unclear.

To investigate the effects of preoperative psychological stress on selected para

Ninety older patients who underwent THA between January 2023 and August 2024 were divided into two groups by their preoperative self-rated anxiety scale and self-rated depression scale scores, including high-stress (n = 42) and low-stress (n = 48). The postoperative joint function, short form-36 health survey (SF-36) score, incidence of postoperative complications, and other indicators were compared between the two groups. Pearson’s correlation coefficient analysis of the relationship among preoperative psychological stress, quality of life, and postoperative complications was performed.

Postoperative joint function and quality of life were lower in the high-stress group than they were in the low-stress group (P < 0.05). The incidence of postoperative complications was higher in the high-stress group (29.27%) than it was in the low-stress group (9.30%) (P < 0.05). Cor

Preoperative psychological stress results in adverse effects on quality of life and complications in older patients undergoing THA. Therefore, pre-operative psychological interventions should be strengthened to improve post-operative outcomes.

Core Tip: We aimed to investigate the effects of preoperative psychological stress on selected parameters in older patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty (THA). After the study, we concluded that preoperative psychological stress resulted in adverse effects on the quality of life and complications in older patients undergoing THA. Therefore, pre-operative psychological interventions should be strengthened to improve post-operative outcomes.

- Citation: Cao JJ, Yin CL, Li XM, Sha XJ, Li L, Sun CY, Zhang LL. Effects of preoperative psychological stress on selected parameters in older patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(8): 103302

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i8/103302.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i8.103302

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is the primary treatment for various bone diseases and can effectively correct deformities, relieve joint pain, improve hip joint function, and speed the patient’s return to normal life[1]. Older individuals are the primary beneficiaries of THA[2]. Although THA can achieve a good therapeutic effect[3], it is more invasive and traumatic, and patients often experience different degrees of psychological stress before surgery, including concerns regarding the results of the operation, fear of complications, and uncertainty regarding the future[4]. Emerging evidence suggests that preoperative psychological stress may impair postoperative recovery through multiple neuroendocrine-immune pathways. Specifically, chronic stress activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and sympathetic nervous system, leading to elevated cortisol and catecholamine levels that suppress lymphocyte proliferation, reduce natural killer cell activity, and dysregulate inflammatory cytokine production. These immunomodulatory effects may increase vulnerability to surgical site infections and delay wound healing[5]. These psychological pressures may also negatively affect rehabilitation after THA[6].

Psychological stress refers to the tension and uneasiness that individuals feel when encountering external stimuli[7] that exceed their adaptive ability and affect their emotions, cognition, and behavior[8]. Psychological pressure exerts a significant effect on postoperative rehabilitation after THA[9]. Beyond the biological mechanisms, stress-induced maladaptive cognition (e.g., catastrophizing and low self-efficacy) may impair rehabilitation adherence through behavioral pathways. Elevated anxiety levels are correlated with reduced engagement in physical activity and poor compliance with postoperative exercise regimens. Furthermore, chronic stress depletes psychological resources and diminishes the patients' capacity to maintain motivation during prolonged recovery[10]. On the one hand, it can lead to a decline in patient immune function and increase the risk of postoperative infection and other complications. Conversely, psychological stress affects the psychological state of patients, produces negative emotions, and affects the subjective well-being and life satisfaction. Psychological pressure also affects patient behavior by reducing compliance and enthusiasm, preventing patients from participating in postoperative rehabilitation training and thus delaying the reco

Therefore, determining the influence of preoperative psychological stress on quality of life and postoperative complications in older patients undergoing THA is of important theoretical and practical significance for designing reasonable preoperative psychological interventions and nursing measures and improving the postoperative rehabilitation effect and quality of life of patients. A deeper understanding of these psychobiological mechanisms could inform targeted inter

The present study was a single-center, retrospective analysis. Data from 90 older patients who underwent THA between January 2023 and August 2024 were collected and divided into two groups according to their preoperative self-rated anxiety scale (SAS) and self-rated depression scale (SDS) scores, including high stress (n = 42) and low stress (n = 48) groups.

Patients fulfilling the following criteria were included: Underwent THA for the first time; were aged > 60 years; pos

Individuals with a history of mental illness, serious heart, liver, kidney, and other organ dysfunction(s), infectious disease(s), or other recent major events affecting psychological status were excluded.

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee, and all patients voluntarily participated.

General information questionnaire: General data questionnaires were designed and included age, sex (male/female), type of disease (femoral neck fracture/rheumatoid arthritis/osteoarthritis/other), body mass index (BMI), duration of surgery, intraoperative blood loss, length of hospital stay, and complications such as diabetes mellitus [in accordance with the clinical guidelines for prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus in the elderly in China (2022 edition)][12] and hypertension (in accordance with the clinical practice guidelines)[13].

Preoperative psychological stress assessment[14]: One day before surgery, all patients were assessed by professionals, and the SAS and SDS were used for quantitative measurements. The total SAS score ranges from 20 to 80 points, and a higher score is indicative of more serious anxiety. The boundary is 50, and ≥ 50 is classified as a state of anxiety[15]. The total SDS score ranges from 20 to 80 points, and a higher score is indicative of a more serious degree of depression. The SDS is divided at 53 points, with ≥ 53 points classified as depression[16]. Older patients who underwent hip replacement and fulfilled any of the following criteria were allocated to the low-stress group: SAS score > 50; SDS score > 53; SAS score > 50; SDS score > 53. Based on these criteria, 42 and 48 patients were assigned to high- and low-stress groups, respectively.

Postoperative joint function[17]: The Harris hip score was used to evaluate hip function recovery at 3 months after surgery. The Harris hip score consists of 12 items that assess pain function, movement, deformation, and muscle strength. The total score ranged from 0 to 100 points. Higher scores indicated better joint function.

Short form-36 health survey score[18]: A higher final score indicates better patient quality of life (total score, 100 points). The short form-36 health survey (SF-36) consists of eight domains (general health, social function, physical function, emotional function, physiological role, physical pain, mental health, and vitality).

Postoperative complications: Postoperative complications in all patients, including infection, bleeding, dislocation, fracture, thrombosis, and nerve injury, were observed and recorded, and the incidence of complications was calculated.

Data collection could only be performed after all researchers were trained and qualified. General patient data were searched and entered into an electronic medical records system. Psychological stress was assessed by the attending nurse within 24 hours after admission, and the recovery of hip function was assessed by a professional physician when the patient was hospitalized for re-examination at 3 months after surgery.

Data analyses were performed using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, United States). Measurement data are expressed as mean ± SD, and the t-test was used for inter-group comparisons. Count data are expressed as frequency and/or percentage, and the Pearson’s χ2 test was used for inter-group comparisons. Pearson’s method was used to analyze the relationships among psychological stress, postoperative quality of life, and complications in older patients undergoing THA. Differences with P < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. The correlation was interpreted as follows: |r| < 0.2 indicates no correlation; 0.2 ≤ |r| < 0.4 signifies a weak correlation; 0.4 ≤ |r| < 0.6 represents a moderate correlation; 0.6 ≤ |r| < 0.8 denotes a strong correlation; |r| ≥ 0.8 indicates an excellent correlation.

Among the 42 patients in the high-stress group, 29 (69%) were male and 13 (31%) were female, with a mean ± SD age of 66.26 ± 4.62 years. Disease types were distributed as follows: Femoral neck fracture (n = 15, 36%); rheumatoid arthritis (n = 10, 24%); osteoarthritis (n = 9, 21%); and others (n = 8, 19%). Among the 48 patients in the low-stress group, 32 (67%) were male and 16 (33%) were female, with a mean age of 65.72 ± 4.53 years. Disease types in this group were distributed as follows: Femoral neck fracture (n = 16, 33%); rheumatoid arthritis (n = 12, 25%); osteoarthritis (n = 11, 23%); and others (n = 9, 19%). There were no statistically significant differences between the 2 groups in terms of age, sex, BMI, disease type, or comorbidities (P > 0.05), indicating that the 2 groups were comparable, as summarized in Table 1.

| Variables | High pressure group (n = 42) | Low pressure group (n = 48) | P value |

| Age (year) | 66.26 ± 4.62 | 65.72 ± 4.53 | 0.519 |

| Sex | 0.709 | ||

| Male | 29 (69) | 32 (67) | |

| Female | 13 (31) | 16 (33) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 22.31 ± 5.77 | 23.74 ± 5.84 | 0.686 |

| Disease type | |||

| Femoral neck fracture | 15 (36) | 16 (33) | 0.881 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 10 (24) | 12 (25) | |

| Osteoarthritis | 9 (21) | 11 (23) | |

| Other | 8 (19) | 9 (19) | |

| Complicated with diabetes | 0.734 | ||

| Yes | 9 (21) | 12 (25) | |

| No | 33 (79) | 36 (75) | |

| Complicated with hypertension | 0.273 | ||

| Yes | 7 (17) | 9 (19) | |

| No | 35 (83) | 39 (81) |

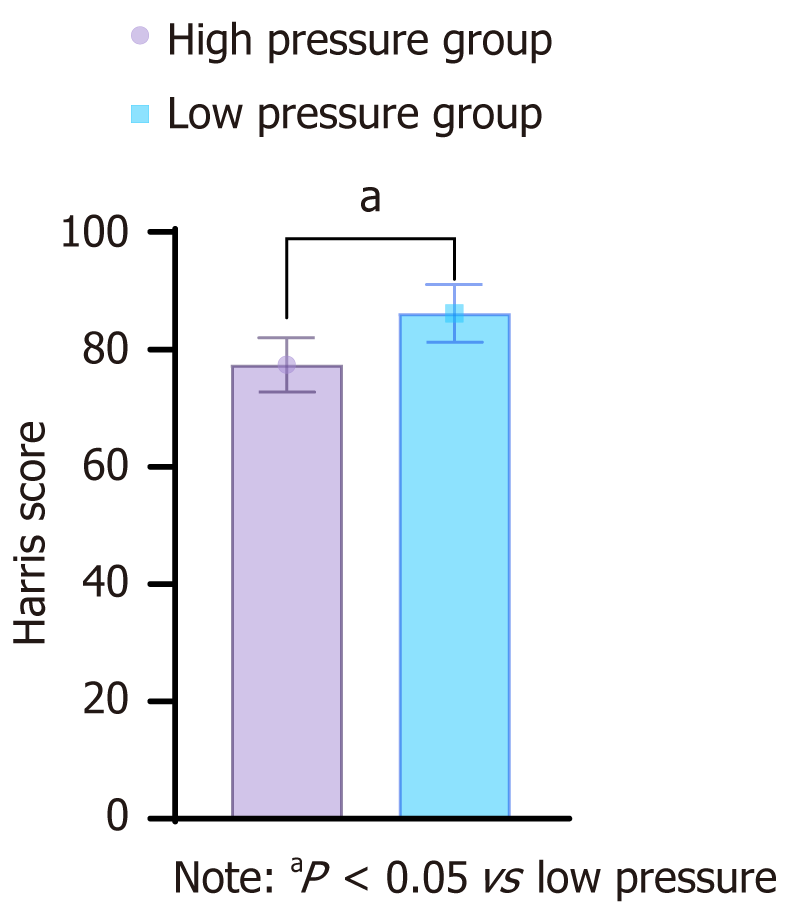

The mean postoperative Harris hip score of patients in the high-stress group (77.36 ± 4.62) was lower than that in the low-stress group (86.12 ± 4.91), with a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) (Figure 1).

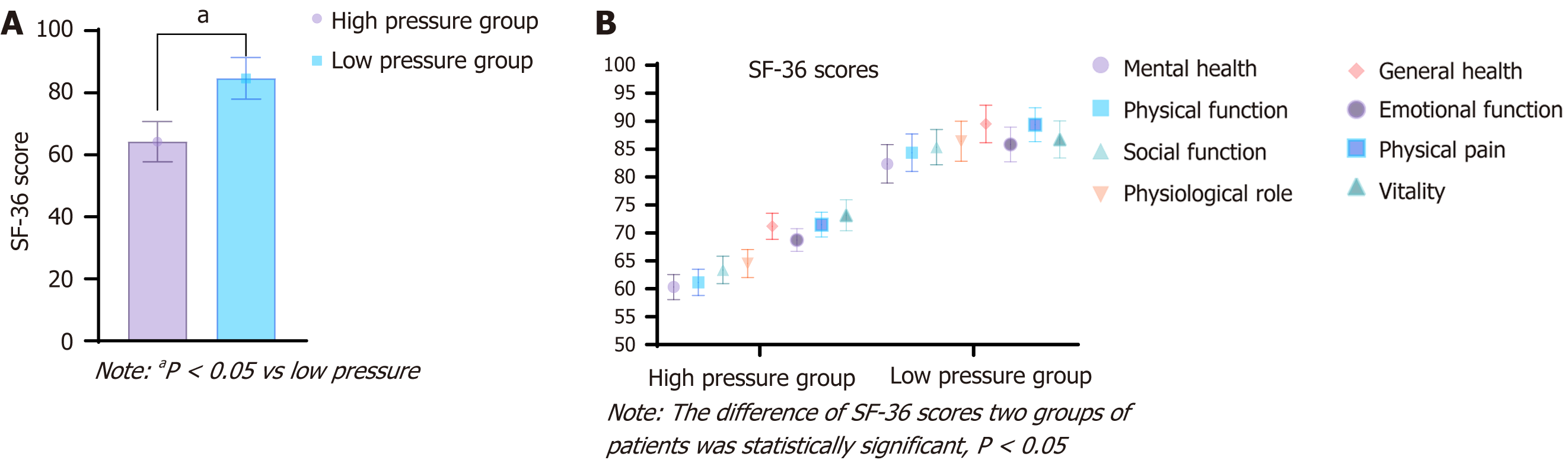

The total score of postoperative SF-36 scale in the high-stress group (64.23 ± 6.52) was lower than that in the low-pressure group (84.67 ± 6.71), and the scores of all dimensions in the high-pressure group were lower than those in the low-pressure group, with a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) (Figure 2).

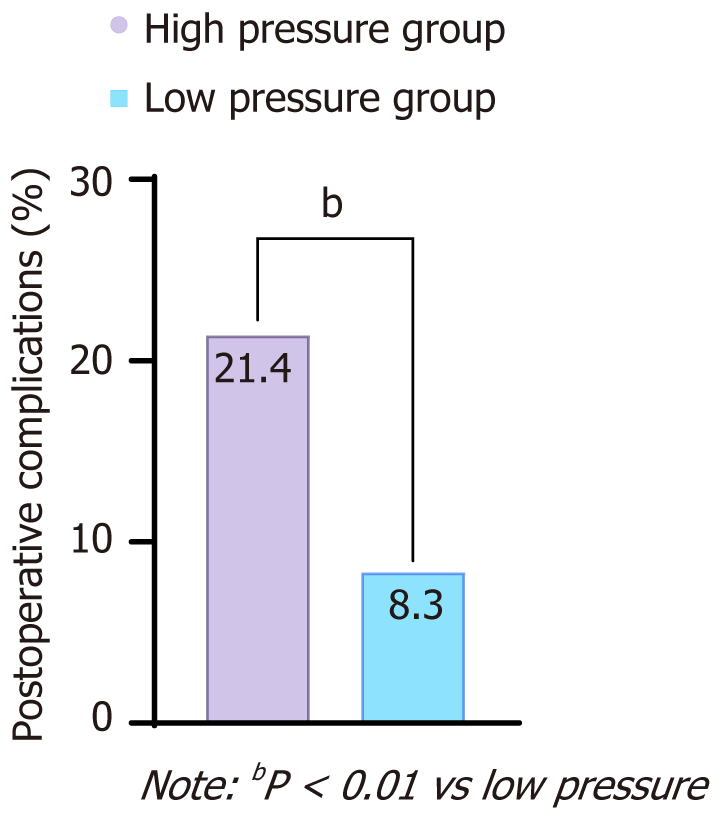

The incidences of postoperative complications were 21.4% (9/42) and 8.3% (4/48) in the high-and low-stress groups, respectively. There was a statistically significant difference in the incidence of postoperative complications between the 2 groups (P < 0.05) (Figure 3).

Correlation analysis revealed that psychological stress was negatively correlated with Harris hip score (r = -0.579, moderate correlation), SF-36 total score(r = -0.636, strong correlation), physical function(r = -0.547, moderate correlation), physical pain(r = -0.635, strong correlation), general health(r = -0.568, moderate correlation), mental health(r = -0.652, strong correlation), social function(r = -0.613, strong correlation), vitality(r = -0.614, strong correlation), emotional function(r = -0.572, moderate correlation), and other scores (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

| Indexes | Preoperative psychological stress | |

| r value | P value | |

| Harris score | -0.579 | < 0.001 |

| Mental health | -0.652 | 0.006 |

| Physical function | -0.547 | < 0.001 |

| Social function | -0.613 | 0.041 |

| Physiological role | -0.576 | < 0.001 |

| General health | -0.568 | < 0.001 |

| Emotional function | -0.572 | < 0.001 |

| Physical pain | -0.635 | 0.032 |

| Vitality | -0.614 | < 0.001 |

| Total SF-36 score | -0.636 | < 0.001 |

THA can improve joint function in patients with bone disease(s) and partly restore their limited activity; however, those affected by pain, reduced self-care ability, and other factors experience greater psychological pressure[19]. Moreover, patients must remain in bed for a prolonged period after surgery, and this can lead to other negative psychological emotions, thus aggravating their psychological stress and rendering them unable to actively cope with the disease, leading to slow recovery of hip function and reduced quality of life[20]. Therefore, implementing targeted measures to facilitate recovery is important. By evaluating preoperative psychological stress levels, quality of life, and postoperative complications in 90 older patients who underwent THA, this study determined that higher preoperative psychological stress was associated with lower postoperative quality of life and a higher incidence of complications. These results are consistent with those of a previous study[6], indicating that preoperative psychological stress is an important factor affecting postoperative rehabilitation and quality of life in older patients undergoing THA and should be considered by clinicians and patients.

Psychological pressure is a cognitive and behavioral experience composed of psychological stressors and psychological stress reactions that can cause a variety of negative emotions in the human body, including anxiety, depression, tension, and fear[21]. Negative emotions can aggravate psychological pressure on patients, forming a vicious cycle that results in adverse effects on their psychological state and affects their rehabilitation state[22]. Studies have reported that anxiety, depression, and other emotions may affect exercise compliance, resulting in poor rehabilitation outcomes[23,24]. Therefore, it is preliminarily speculated that relieving psychological pressure may exert a positive impact on the recovery of hip function. Results of the present study revealed that the mean postoperative Harris hip score of patients in the high-stress group (77.36 ± 4.62) was lower than that of those in the low-stress group (86.12 ± 4.91), and the difference was statistically significant (P < 0.05). The total score of the postoperative SF-36 scale in the high-stress group (64.23 ± 6.52) was lower than that in the low-stress group (84.67 ± 6.71), and the scores of all dimensions in the high-stress group were lower than those in the low-stress group, with statistical significance (P < 0.05). The incidence of postoperative complications was significantly lower in the high-stress group (21.4%) than it was in the low-stress group (8.3%) (P < 0.05). Correlation analysis revealed that psychological stress was negatively correlated with Harris hip score, SF-36 total score, physical function, physical pain, general health, mental health, social function, vitality, emotional function, and other scores (P < 0.05). The results of this study are basically consistent with those of previous studies[25,26]. The reason for the analysis is that, on the one hand, anxiety, depression and other emotions, as a negative psychological state, can impose a burden on patient physiology and psychology. Owing to long-term pain, the quality of life of patients is significantly reduced. Coupled with the restriction of limb functional activities and poor self-care ability, negative emotions were significantly aggravated. Conversely, although surgery can improve the physical function of patients, the economic pressure associated with treatment and rehabilitation easily causes a burden on patient psychology, resulting in heavy psychological negative emotions of patients, thus rendering them unable to maintain a positive rehabilitation mentality.

To reduce preoperative psychological pressure in older patients undergoing THA and to improve postoperative joint function recovery and quality of life, the following clinical measures should be implemented. The first involves stren

This study possesses several limitations. First, we adopted a single-center retrospective design that restricted our ability to fully control for confounding factors that may influence the results, including variables related to genetics, envi

In conclusion, preoperative psychological stress levels exert a significant impact on postoperative joint function recovery, quality of life, and postoperative complications in older patients undergoing THA. Preoperative psychological inter

| 1. | Wong JRY, Gibson M, Aquilina J, Parmar D, Subramanian P, Jaiswal P. Pre-Operative Digital Templating Aids Restoration of Leg-Length Discrepancy and Femoral Offset in Patients Undergoing Total Hip Arthroplasty for Primary Osteoarthritis. Cureus. 2022;14:e22766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chen J, Zhu W, Zhang Z, Zhu L, Zhang W, DU Y. Efficacy of celecoxib for acute pain management following total hip arthroplasty in elderly patients: A prospective, randomized, placebo-control trial. Exp Ther Med. 2015;10:737-742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wang J, Deng Z, Huang B, Zhao Z, Wan H, Ding H. The short-term outcomes of cementless stem for hip arthroplasty in the elderly patients: comparison with patients < 65 years. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2022;23:1070. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mears DC. CORR Insights(®): does preoperative psychologic distress influence pain, function, and quality of life after TKA? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:2466-2467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Spiers JG, Chen HJ, Sernia C, Lavidis NA. Activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal stress axis induces cellular oxidative stress. Front Neurosci. 2014;8:456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jones AR, Al-Naseer S, Bodger O, James ETR, Davies AP. Does pre-operative anxiety and/or depression affect patient outcome after primary knee replacement arthroplasty? Knee. 2018;25:1238-1246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Alattas SA, Smith T, Bhatti M, Wilson-Nunn D, Donell S. Greater pre-operative anxiety, pain and poorer function predict a worse outcome of a total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2017;25:3403-3410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Dash SK, Palo N, Arora G, Chandel SS, Kumar M. Effects of preoperative walking ability and patient's surgical education on quality of life and functional outcomes after total knee arthroplasty. Rev Bras Ortop. 2017;52:435-441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hanusch BC, O'Connor DB, Ions P, Scott A, Gregg PJ. Effects of psychological distress and perceptions of illness on recovery from total knee replacement. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B:210-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Doo EY, Kim JH. Parental smartphone addiction and adolescent smartphone addiction by negative parenting attitude and adolescent aggression: A cross-sectional study. Front Public Health. 2022;10:981245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Valenzuela R, Ziegelmann M, Tokar S, Hillelsohn J. The use of penile traction therapy in the management of Peyronie's disease: current evidence and future prospects. Ther Adv Urol. 2019;11:1756287219838139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chinese Elderly Type 2 Diabetes Prevention and Treatment of Clinical Guidelines Writing Group; Geriatric Endocrinology and Metabolism Branch of Chinese Geriatric Society; Geriatric Endocrinology and Metabolism Branch of Chinese Geriatric Health Care Society; Geriatric Professional Committee of Beijing Medical Award Foundation; National Clinical Medical Research Center for Geriatric Diseases (PLA General Hospital). [Clinical guidelines for prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus in the elderly in China (2022 edition)]. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 2022;61:12-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chinese Society of Cardiology; Chinese Medical Association; Hypertension Committee of Cross-Straits Medicine Exchange Association; Cardiovascular Disease Prevention and Rehabilitation Committee, Chinese Association of Rehabilitation Medicine. [Clinical practice guidelines for the management of hypertension in China]. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2024;52:985-1032. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yu T, Shen X, Li M, Wang M, Lin L. Efficacy and Predictors for Biofeedback Therapeutic Outcome in Patients with Dyssynergic Defecation. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2017;2017:1019652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Turzáková J, Sollár T, Solgajová A. Faces Anxiety Scale as a screening measure of preoperative anxiety: Validation and diagnostic accuracy study. Int J Nurs Pract. 2019;25:e12758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Dunstan DA, Scott N. Norms for Zung's Self-rating Anxiety Scale. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20:90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 312] [Article Influence: 62.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Krishna V, Venkatesan A, Singh AK. Functional and Radiological Outcomes of Unstable Proximal Femur Fractures Fixed With Anatomical Proximal Locking Compression Plate. Cureus. 2022;14:e24903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Li XJ, Dai ZY, Zhu BY, Zhen JP, Yang WF, Li DQ. Effects of sertraline on executive function and quality of life in patients with advanced cancer. Med Sci Monit. 2014;20:1267-1273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sorel JC, Veltman ES, Honig A, Poolman RW. The influence of preoperative psychological distress on pain and function after total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bone Joint J. 2019;101-B:7-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Rajamäki TJ, Moilanen T, Puolakka PA, Hietaharju A, Jämsen E. Is the Preoperative Use of Antidepressants and Benzodiazepines Associated with Opioid and Other Analgesic Use After Hip and Knee Arthroplasty? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2021;479:2268-2280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ardon AE, Baloach AB, Matveev S, Colontonio MM, Narciso PM, Spaulding A. Preoperative anxiolytic and antidepressant medications as risk factors for increased opioid use after total knee arthroplasty: a matched retrospective cohort analysis. Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 2023;55:205-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Rong Y, Hao Y, Wei D, Li Y, Chen W, Wang L, Li T. Association between preoperative anxiety states and postoperative complications in patients with esophageal cancer and COPD: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Cancer. 2024;24:606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Varış O, Peker G. Effects of preoperative anxiety level on pain level and joint functions after total knee arthroplasty. Sci Rep. 2023;13:20787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Pan X, Wang J, Lin Z, Dai W, Shi Z. Depression and Anxiety Are Risk Factors for Postoperative Pain-Related Symptoms and Complications in Patients Undergoing Primary Total Knee Arthroplasty in the United States. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34:2337-2346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Riddle DL, Perera RA, Nay WT, Dumenci L. What Is the Relationship Between Depressive Symptoms and Pain During Functional Tasks in Persons Undergoing TKA? A 6-year Perioperative Cohort Study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:3527-3534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hadlandsmyth K, Sabic E, Zimmerman MB, Sluka KA, Herr KA, Clark CR, Noiseux NO, Callaghan JJ, Geasland KM, Embree JL, Rakel BA. Relationships among pain intensity, pain-related distress, and psychological distress in pre-surgical total knee arthroplasty patients: a secondary analysis. Psychol Health Med. 2017;22:552-563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |