Published online Jun 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i6.105855

Revised: March 25, 2025

Accepted: April 18, 2025

Published online: June 19, 2025

Processing time: 92 Days and 2.3 Hours

As the aging process has accelerated, psychological problems in older patients with chronic heart failure (CHF) have become increasingly prominent, significantly affecting their quality of life and prognosis. This study explored a sports rehabilitation program based on the concept of medical care-family integration to provide patients with comprehensive and effective rehabilitation interventions and improve their health status.

To explore the effects of medical care-family integration-based exercise rehabilitation in older patients with CHF and psychological problems.

Data from 118 older patients with CHF and psychological problems were retrospectively analyzed. Patients were divided into conventional (n = 56) and exercise rehabilitation groups (n = 62). The results of the 6-min walking distance (6 MWD), N-terminal B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD), left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), Minnesota living with heart failure questionnaire (MLHFQ), generalized anxiety disorder-7 (GAD-7) scale, 9-item patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) and Athens insomnia scale (AIS) were compared before and after intervention.

After intervention, there were significant differences in the number of patients with depression and anxiety between the two groups. There was also a significant difference in the distribution of sleep disorders. The PHQ-9 score, GAD-7 score, AIS score, NT-proBNP value, LVEDD value, physical field, emotional field, other fields, and MLHFQ total scores were lower in the exercise rehabilitation group compared to the conventional rehabilitation group, while the 6 MWD and LVEF values were higher compared to the conventional rehabilitation group (P < 0.05). During the intervention period, the readmission rate of the exercise rehabilitation group (1.61%) was significantly lower than that of the conventional rehabilitation group (12.50%) (χ2 = 3.930, P = 0.047).

This exercise rehabilitation program with medical care-family integration can improve cardiac function and quality of life, alleviate psychological problems, and reduce readmission rates in older patients with CHF.

Core Tip: This study explored an exercise rehabilitation program based on the concept of medical care-family integration for older patients with chronic heart failure and psychological problems. Compared to conventional rehabilitation, this approach significantly improved cardiac function, reduced anxiety, depression, and sleep disorders, enhanced quality of life, and decreased readmission rates. By integrating medical support with active family involvement, this model offers an innovative and effective rehabilitation strategy for clinical practice.

- Citation: Ao C, Hu S, Zhan L. Exercise rehabilitation based on medical care-family integration in older patients with chronic heart failure and psychological problems. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(6): 105855

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i6/105855.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i6.105855

Chronic heart failure (CHF) refers to a syndrome of abnormal cardiac structure or function, leading to impaired ventricular filling or ejection ability, an inability to meet the needs of the body, and symptoms such as dyspnea and edema[1]. In older adults, CHF not only affects quality of life but also often leads to respiratory infections, cardiogenic cirrhosis, thrombosis, and other serious complications, even increasing the risk of falls, disability, and death[2]. Psychological problems are particularly prominent among older patients with CHF, including anxiety and depression. These psychological problems not only affect patient mood, sleep quality, and quality of life, but also exacerbate the symptoms of heart failure, leading to recurrence and deterioration of the condition. Simultaneously, a poor psychological state affects the treatment of heart failure and increases medical burden[3-5]. Therefore, it is essential to manage the mental and psychological problems during the rehabilitation of older patients with CHF.

As a nondrug treatment, exercise rehabilitation has a significant effect on the treatment of older patients with CHF. Reasonable exercise rehabilitation can improve cardiac function and quality of life, reduce readmission rates, and prolong survival[6]. However, owing to the particularity of their physical condition and mental state, older patients with CHF and psychological problems face many challenges in exercise rehabilitation, such as insufficient exercise endurance and difficulty implementing exercise programs[7].

In recent years, the concept of medical care-family integration has been gradually applied in the management of chronic diseases, which emphasizes close cooperation between hospitals and families to provide continuous and comprehensive medical care[8]. In exercise rehabilitation, the application of the medical care-family integration concept can ensure the safety and effectiveness of exercise rehabilitation and provide continuous guidance and support in the family environment to improve patient compliance and rehabilitation effects[9]. There has been progress in the research of rehabilitation of patients with CHF; however, there are still many limitations. For example, there have been few studies on exercise rehabilitation in older patients with CHF and psychological problems[10]. Furthermore, there is still a lack of systematic and comprehensive evaluation.

Therefore, this study aimed to construct an exercise rehabilitation program for older patients with CHF who have mental and psychological problems and evaluate the effects of its application, to provide new ideas and methods for their exercise rehabilitation and help them better manage the disease and improve their quality of life.

The clinical data of 118 older patients with CHF admitted to our hospital between June 2023 and June 2024 were retrospectively analyzed. The patients were clinically diagnosed with depression or anxiety. Older patients with CHF were divided into conventional and exercise rehabilitation groups based on the different rehabilitation interventions. Patients with CHF receiving routine rehabilitation intervention were included in the conventional rehabilitation group (n = 56), and those receiving exercise rehabilitation intervention based on medical care-family integration were included in the exercise rehabilitation group (n = 62). This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical and Pharmaceutical College. The requirement for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Inclusion criteria: (1) Age ≥ 60 years; (2) Meet the diagnostic criteria of CHF in the Chinese Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Heart Failure 2024[11]; (3) 9-item patient health questionnaire (PHQ-9) and generalized anxiety disorder-7 (GAD-7) scales used for evaluation and patients diagnosed with depression or anxiety[12,13]; (4) New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class II–III; (5) No serious dysfunction of important organs (brain, liver, lung, or kidney); (6) Good function of both lower limbs; and (7) Clear consciousness, smooth communication, and complete cognitive behavior ability.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Acute coronary syndrome, new-onset atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter, acute pericarditis or myocarditis, uncontrolled hypertension or malignant arrhythmia, severe hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy, advanced atrioventricular block, ventricular aneurysm, venous thrombosis; (2) Severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cor pulmonale, or respiratory failure; (3) End stage of disease or without voluntary activity; (4) Mental disorder or cognitive impairment; (5) Pulmonary infection; and (6) Incomplete clinical data.

Patients in the conventional rehabilitation group were treated using a routine exercise rehabilitation program. They were provided with routine drugs, exercise, nutrition, and psychological guidance. Regular follow-up was conducted to assess the effects of exercise, cardiac function changes, and mental health, and certain out-of-hospital guidance was provided. Basic family care guidance was provided, but deep participation and continuous supervision of family members were not emphasized.

Patients in the exercise rehabilitation group were treated using an exercise rehabilitation program based on medical care-family integration, following the conventional rehabilitation group[14].

Team formation and training: A medical care-family integrated team comprising cardiovascular doctors, rehabilitation doctors, psychological counselors, nurses, and family members was formed. Professional training in heart failure management, exercise rehabilitation, mental and psychological support was provided for team members to ensure that they have professional knowledge and skills and are competent in their respective responsibilities.

Comprehensive evaluation: Referring to the "Expert Consensus on Cardiac Rehabilitation for chronic heart failure in China"[15], a comprehensive medical evaluation, including cardiac function assessment (such as echocardiography), exercise capacity [such as 6-min walk test (6 MWT)], mental and psychological state assessment (such as anxiety and depression assessment), of patients was performed. Simultaneously, the quality of daily life and family environment of the patients were evaluated to understand their rehabilitation needs and expectations.

Development of a personalized rehabilitation plan: Based on the evaluation results, a personalized exercise rehabilitation plan was formulated for patients. Each plan comprehensively considered cardiac function, exercise ability, mental state, daily living habits, and other factors to ensure the safety and effectiveness of exercise. The exercise environment was confirmed to be safe, comfortable, and suitable for the patient to perform rehabilitation exercises. If conducted in a home environment, sufficient space and facilities to meet the patient’s exercise needs were required. The main type of exercise was aerobics, such as walking, cycling, and swimming, supplemented by resistance, flexibility, and balance exercises. Exercise intensity was determined using the heart rate reserve method (HRR) outlined in the "Expert Consensus on Cardiac Rehabilitation for chronic heart failure in China"[15]. The specific formula is as follows: target heart rate = (maximum heart rate-resting heart rate) × target intensity % + resting heart rate. The initial stage started at 40% HRR, and the intensity increased by 10% every 2 weeks, with the final goal reaching 80% HRR. During exercise, real-time monitoring through wearable electrocardiogram monitoring equipment ensured that the patient's heart rate fluctuation remained within the target heart rate range of ± 5 beats/min. Exercise frequency was be arranged according to the rehabilitation needs of the patient and the exercise plan, generally 3-5 times per week, with each exercise session lasting approximately 30-60 minutes.

Mental and psychological support: Psychological counselors regularly conduct mental and psychological assessments to understand patients’ emotional states and psychological needs. According to the assessment results, psychological counselors provide personalized psychological support and interventions, such as psychological counseling and psychoeducation, to relieve patients’ anxiety, depression, and other emotional problems. Simultaneously, patients can be psychologically educated on the impact of mental and psychological problems on recovery and how to manage these problems. Through education, patients can learn how to maintain positive attitudes, establish confidence in rehabilitation, and increase their enthusiasm.

Family training: Medical staff provided training to family members on heart failure management and exercise rehabilitation, enabling them to gain basic knowledge of heart failure, the significance and methods of rehabilitation, and in how to assist and supervise the rehabilitation process of patients in the family environment. The training focused on strengthening the three core abilities of family members: (1) Teaching abdominal breathing techniques and guiding family members to assist patients in taking a semi-reclining position for diaphragm training, which included 10 deep breathing exercises in each of 3 sets per day, while simultaneously monitoring changes in blood oxygen saturation; (2) Establishing an early warning response mechanism to identify and address critical signs such as worsening dyspnea (resting SpO2 < 90%), lower limb edema progression (weight gain > 2 kg within 3 days), and paroxysmal dyspnea attack at night; and (3) Standardizing the family exercise monitoring standards with Bluetooth heart rate monitoring equipment, training family members to track the target heart rate interval, assess consciousness and fatigue using the Borg scale (maintaining a score of 11-13), and observe post-exercise recovery.

Emotional support: Family members were encouraged to participate in the patients’ rehabilitation activities, and emotional support and psychological comfort were provided to enhance the patients’ rehabilitation confidence and enthusiasm. Family members learned simple rehabilitation techniques and methods such as massage and deep breathing under the guidance of rehabilitation therapists to assist patients in rehabilitation training.

Communication and collaboration: A medical care-family communication mechanism was established. Through the establishment of a WeChat group, a team of medical staff and family members of the patient were invited to join, and the progress, problems, and adjustment plans for the patient’s rehabilitation were reported and discussed in detail. Family members provided regular feedback to medical staff on the patient’s rehabilitation, while medical staff provided remote guidance and support to ensure that the patient’s rehabilitation process in the family environment received continuous professional attention.

Both the conventional and exercise rehabilitation groups received rehabilitation intervention for 3 months and completed the follow-up evaluation after 3 months. The 6-min walking distance (6 MWD), N-terminal B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) level, left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD), left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), Minnesota living with heart failure questionnaire (MLHFQ), GAD-7, PHQ-9, and Athens insomnia scale (AIS) were used to evaluate cardiac function, quality of life, depression, and anxiety before and after intervention and readmission rate during rehabilitation to fully understand and evaluate the effects of exercise rehabilitation on patients.

Cardiac function indicators: NT-proBNP: Elevation of NT-proBNP level is directly proportional to the severity of heart failure, which is the gold standard for assessing heart failure. The fasting venous blood of patients in the two groups was collected before and after the rehabilitation intervention, and changes in plasma NT-proBNP levels were measured using immunofluorescence chromatography.

Echocardiographic parameters: Changes in LVEF and LVEDD before and after the rehabilitation intervention were monitored by a dedicated echocardiologist using a color Doppler detector.

6 MWT: The 6 MWT was conducted in a 30 m flat and straight corridor. The starting and turning points were marked, and each patient walked back and forth along the straight path according to the set point. Walking speed was determined based on the patient’s physical ability according to the usual normal walking speed, and the 6 MWD was recorded. The patient’s exercise tolerance and cardiac function were assessed by distance traveled[16].

Quality of life: The MLHFQ was used for evaluating quality of life. The MLHFQ, developed by Rector and Cohn[17], is a research tool specific to heart failure. The scale has three dimensions and 21 items: physical (8 items, 0-40 points), emotional (5 items, 0-25 points), and other fields (8 items, 0-40 points). The total score was 0-105 points. Higher scores indicate poorer quality of life. The Cronbach's α coefficient of the total scale was 0.91, and the reliability and validity were good[18].

Psychological problems: Depression: The PHQ-9 was used to assess depression severity and included nine items: reduced interest, low mood, difficulty falling asleep, fatigue, poor appetite, poor feelings, decreased attention, slow movement, and suicidal thoughts. Each item was scored from 0 to 3, with 0 indicating not at all, 1 indicating a few days, 2 indicating more than half of the days, and 3 indicating almost every day. The maximum score was 27, with a score of 0-4 indicating "no depression", a score of 5-9 indicating "mildly depressed state", a score of 10-14 indicating "moderately depressed state", a score of 15-19 indicating "moderately severely depressed state", and a score of 20–27 indicating "severely depressed state". The Cronbach's α value of the PHQ-9 scale was 0.83[19].

Anxiety: The GAD-7 was used to evaluate anxiety and included seven items: feeling nervous, anxious, or on-edge; unable to stop or control worrying; worrying too much about different things; trouble relaxing; being so restless it is hard to sit still; becoming easily annoyed or irritable; and feeling afraid as if something awful might happen. Each item was scored from 0 to 3, with 0 indicating not at all, 1 indicating a few days, 2 indicating more than half of the days, and 3 indicating almost every day. The maximum score was 21, with 0-4 indicating "no anxiety", 5-9 indicating "mild anxiety", 10-13 indicating "moderate anxiety", and 14-18 indicating "moderate-to-severe anxiety". A score of 19-21 indicated a "state of severe anxiety". The Cronbach's α value of the GAD-7 was 0.869[20].

Sleep disorder: The AIS was used to evaluate the severity of sleep disorders. This index involves a self-rating scale based on the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition criteria for insomnia. Eight questions were included, with the first five assessing nighttime sleep and the last three assessing daytime function. Each item was scored on a scale of 0 to 3, with a total score of 0 to 24. A total score of less than 4 indicated no sleep disorder, 4 to 6 indicated indicating insomnia, and > 6 indicated insomnia. The Cronbach's α of the AIS scale was 0.90[21].

Readmission rate: The readmission rate of patients during the rehabilitation intervention was recorded.

Data were analyzed using SPSS software (version 26.0). Count data are presented as n (%), and χ2 test was used for analysis. Rank data were analyzed using the rank-sum test. Measurement data that were normally distribution were described by (mean ± SD), and a t-test was used. Otherwise, the interquartile range was used for descriptive analysis, and the Mann-Whitney U test was used for comparison. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

We did not identify any significant differences in sex, age, body mass index, disease course, marital status, education level, NYHA cardiac function classification, smoking history, drinking history, hypertension, or diabetes between the two groups (P > 0.05) (Table 1).

| Category | Conventional rehabilitation | Exercise rehabilitation | t/χ2/Z | P value |

| Sex | 0.969 | 0.325 | ||

| Female | 22 (39.29) | 19 (29.69) | ||

| Male | 34 (60.71) | 43 (67.19) | ||

| Age (years) | 68.66 ± 3.18 | 69.34 ± 3.61 | 1.076 | 0.284 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.02 ± 3.07 | 26.69 ± 3.40 | 1.120 | 0.265 |

| Course of disease (years) | 4.05 ± 1.04 | 3.82 ± 1.00 | 1.222 | 0.224 |

| Marital status | 0.794 | 0.373 | ||

| Divorced/widowed | 9 (16.07) | 14 (22.58) | ||

| Married | 47 (83.93) | 48 (77.42) | ||

| Education level | 1.110 | 0.292 | ||

| Below high school | 42 (75.00) | 41 (66.13) | ||

| High school and above | 14 (25.00) | 21 (33.87) | ||

| New York Heart Association cardiac function classification | 0.357 | 0.550 | ||

| Grade Ⅱ | 35 (62.50) | 42 (67.74) | ||

| Grade Ⅲ | 21 (37.50) | 20 (32.26) | ||

| Smoking | 0.355 | 0.552 | ||

| No | 11 (19.64) | 15 (24.19) | ||

| Yes | 45 (80.36) | 47 (75.81) | ||

| Drinking | 0.921 | 0.337 | ||

| No | 15 (26.79) | 12 (19.35) | ||

| Yes | 41 (73.21) | 50 (80.65) | ||

| Hypertension | 0.088 | 0.767 | ||

| No | 25 (44.64) | 26 (41.94) | ||

| Yes | 31 (55.36) | 36 (58.06) | ||

| Diabetes | 0.945 | 0.331 | ||

| No | 33 (58.93) | 31 (50.00) | ||

| Yes | 23 (41.07) | 31 (50.00) |

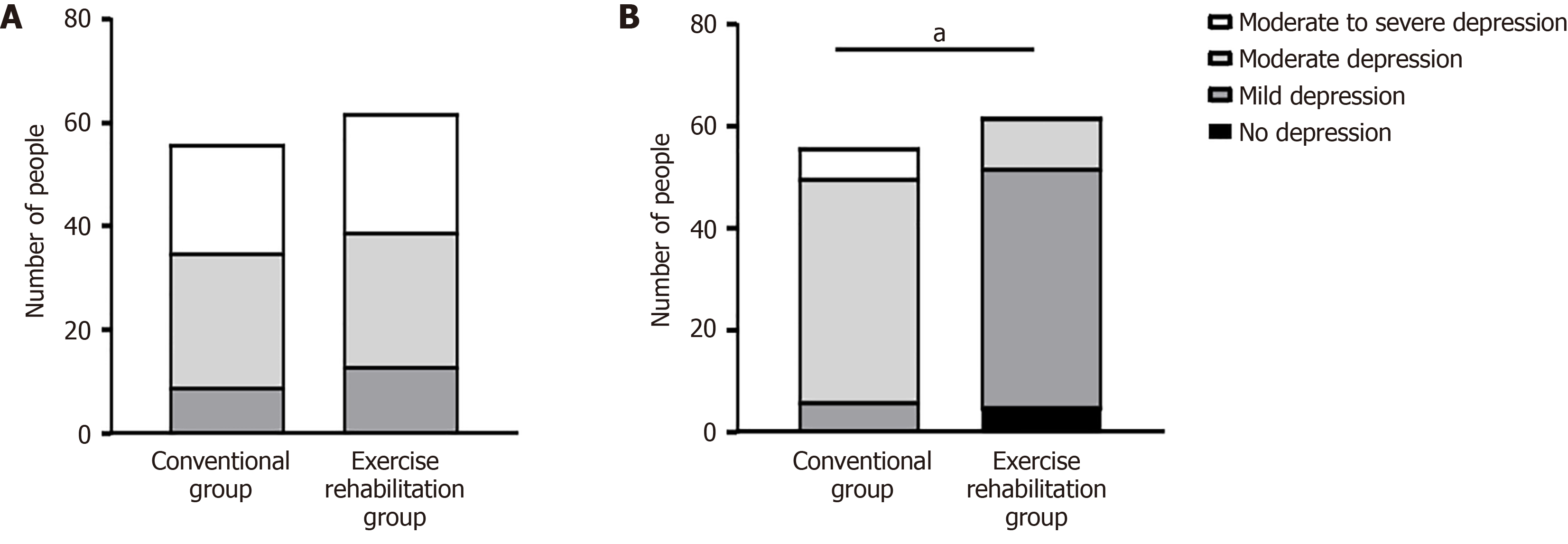

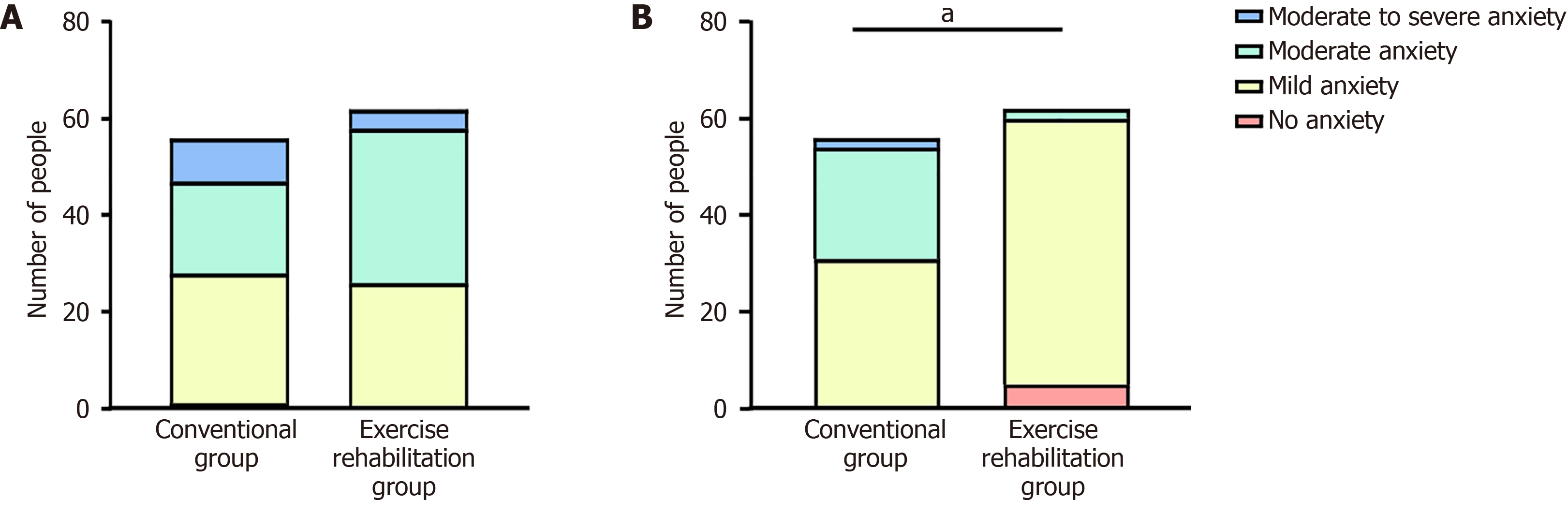

Before the intervention, 117 older patients had CHF, depression, and anxiety, and 1 older patient had CHF and depression. In the conventional rehabilitation group, 9 patients had mild depression, 26 had moderate depression, and 21 had moderate-to-severe depression. Overall, 1 participant had no anxiety, 27 had mild anxiety, 19 had moderate anxiety, and 9 had severe anxiety. In the exercise rehabilitation group, 13 patients had mild depression, 26 had moderate depression, and 23 had moderate-to-severe depression. Overall, 26 patients had mild anxiety, 32 had moderate anxiety, and 4 had moderate-to-severe anxiety. There was no significant difference in the distribution of depression and anxiety between the two groups (Z = 0.344, P = 0.731; Z = 0.278, P = 0.781, respectively) (Figures 1A and 2A). All patients had AIS scores > 6 and insomnia.

After conventional rehabilitation, 6 patients had mild depression, 44 had moderate depression, and 6 had moderate-to-severe depression, while 31 had mild anxiety, 23 had moderate anxiety, and 2 had severe anxiety. Meanwhile, after exercise rehabilitation, 5 patients had no depression, 47 had mild depression, and 10 had moderate depression, while 5 patients had no anxiety, 55 had mild anxiety, and 2 had moderate anxiety. There were significant differences in the number of patients with depression and anxiety between the two groups (Z = 7.858, P < 0.001; Z = 5.540, P < 0.001, respectively) (Figures 1B and 2B). In the conventional treatment group, 0 patients had no sleep disorders, 0 had possible insomnia, and 56 had insomnia. In the exercise rehabilitation group, 4 people had no sleep disorders, 20 had possible insomnia, and 38 had insomnia. The difference between the two groups was statistically significant (Z = -4.818, P < 0.001) (Table 2).

| No sleep disorder | May have insomnia | Have insomnia | ||||

| Before intervention | After intervention | Before intervention | After intervention | Before intervention | After intervention | |

| Conventional rehabilitation group (n = 56) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 56 (100.00) | 56 (100.00) |

| Exercise rehabilitation group (n = 62) | 0 (0.00) | 4 (6.45) | 0 (0.00) | 20 (32.26) | 62 (100.00) | 38 (61.29) |

| Z | -4.818 | |||||

| P value | < 0.001 | |||||

Before intervention, there were no significant differences in the PHQ-9, GAD-7, or AIS scores between the two groups (P > 0.05). After intervention, the PHQ-9, GAD-7, and AIS scores were significantly lower in the exercise rehabilitation group than in the conventional rehabilitation group (P < 0.05). The PHQ-9, GAD-7, and AIS scores of the two groups were significantly lower after the intervention than before the intervention (P < 0.05) (Table 3).

| Items | Conventional rehabilitation | Exercise rehabilitation | t/Z | P value | |

| PHQ-9 score | Before intervention | 14 (11, 16) | 12.5 (10, 15.25) | 0.620 | 0.535 |

| After intervention | 12 (10, 13)a | 7 (5, 9)a | 8.403 | < 0.001 | |

| GAD-7 score | Before intervention | 9.5 (9, 13) | 11 (8, 12) | 0.442 | 0.658 |

| After intervention | 9 (8, 10)a | 6 (5, 7)a | 8.199 | < 0.001 | |

| AIS score | Before intervention | 14.79 ± 2.61 | 13.82 ± 3.09 | 1.191 | 0.236 |

| After intervention | 15.34 ± 2.44a | 7.15 ± 2.30a | 13.379 | < 0.001 |

Before intervention, there were no significant differences in the 6 MWD, NT-proBNP level, LVEF, or LVEDD between the two groups (P > 0.05). After intervention, the 6 MWD and LVEF were higher, while the NT-proBNP level and LVEDD were significantly lower in the exercise rehabilitation group compared to the conventional rehabilitation group (P < 0.05). The 6 MWD and LVEF of the two groups were higher, while the LVEDD was lower after intervention than before intervention. The NT-proBNP level in the exercise rehabilitation group was significantly lower after intervention than before intervention (P < 0.05) (Table 4).

| Items | Conventional rehabilitation | Exercise rehabilitation | t | P value | |

| 6 MWD (m) | Before intervention | 312.78 ± 41.19 | 316.32 ± 43.69 | 0.452 | 0.652 |

| After intervention | 333.49 ± 55.42a | 389.38 ± 42.74a | 6.167 | < 0.001 | |

| NT-proBNP (ng/L) | Before intervention | 498.41 ± 54.71 | 496.94 ± 68.89 | 0.130 | 0.897 |

| After intervention | 490.55 ± 58.49 | 391.44 ± 48.26a | 10.075 | < 0.001 | |

| LVEF (%) | Before intervention | 39.43 ± 3.64 | 40.15 ± 4.04 | 1.008 | 0.315 |

| After intervention | 40.61 ± 4.98a | 46.47 ± 5.36a | 6.139 | < 0.001 | |

| LVEDD (mm) | Before intervention | 55.66 ± 5.31 | 54.37 ± 4.42 | 1.439 | 0.153 |

| After intervention | 53.96 ± 5.10a | 49.31 ± 4.56a | 5.234 | < 0.001 |

Before intervention, there were no significant differences in the physical, emotional, and other fields and the total MLHFQ score between the two groups (P > 0.05). After intervention, the physical, emotional, and other field scores and the total score of the MLHFQ were significantly lower in the exercise rehabilitation group compared to the conventional rehabilitation group (P < 0.05). The physical, emotional, other fields, and total MLHFQ scores of the two groups were significantly lower after intervention than before intervention (P < 0.05) (Table 5).

| Items | Conventional rehabilitation group (n = 56) | Exercise rehabilitation group (n = 62) | t | P value | |

| Physical field | Before intervention | 25.96 ± 5.20 | 26.85 ± 5.08 | 0.940 | 0.349 |

| After intervention | 24.16 ± 4.99a | 19.47 ± 4.72a | 5.246 | < 0.001 | |

| Emotional field | Before intervention | 14.71 ± 3.21 | 14.29 ± 2.80 | 0.767 | 0.444 |

| After intervention | 13.89 ± 3.40a | 7.97 ± 2.58a | 10.727 | < 0.001 | |

| Other field | Before intervention | 18.54 ± 3.85 | 19.11 ± 3.61 | 0.841 | 0.402 |

| After intervention | 17.46 ± 4.52a | 11.24 ± 3.63a | 8.272 | < 0.001 | |

| Total score | Before intervention | 59.21 ± 7.59 | 60.26 ± 6.46 | 0.807 | 0.422 |

| After intervention | 55.52 ± 7.10a | 38.68 ± 5.92a | 14.039 | < 0.001 |

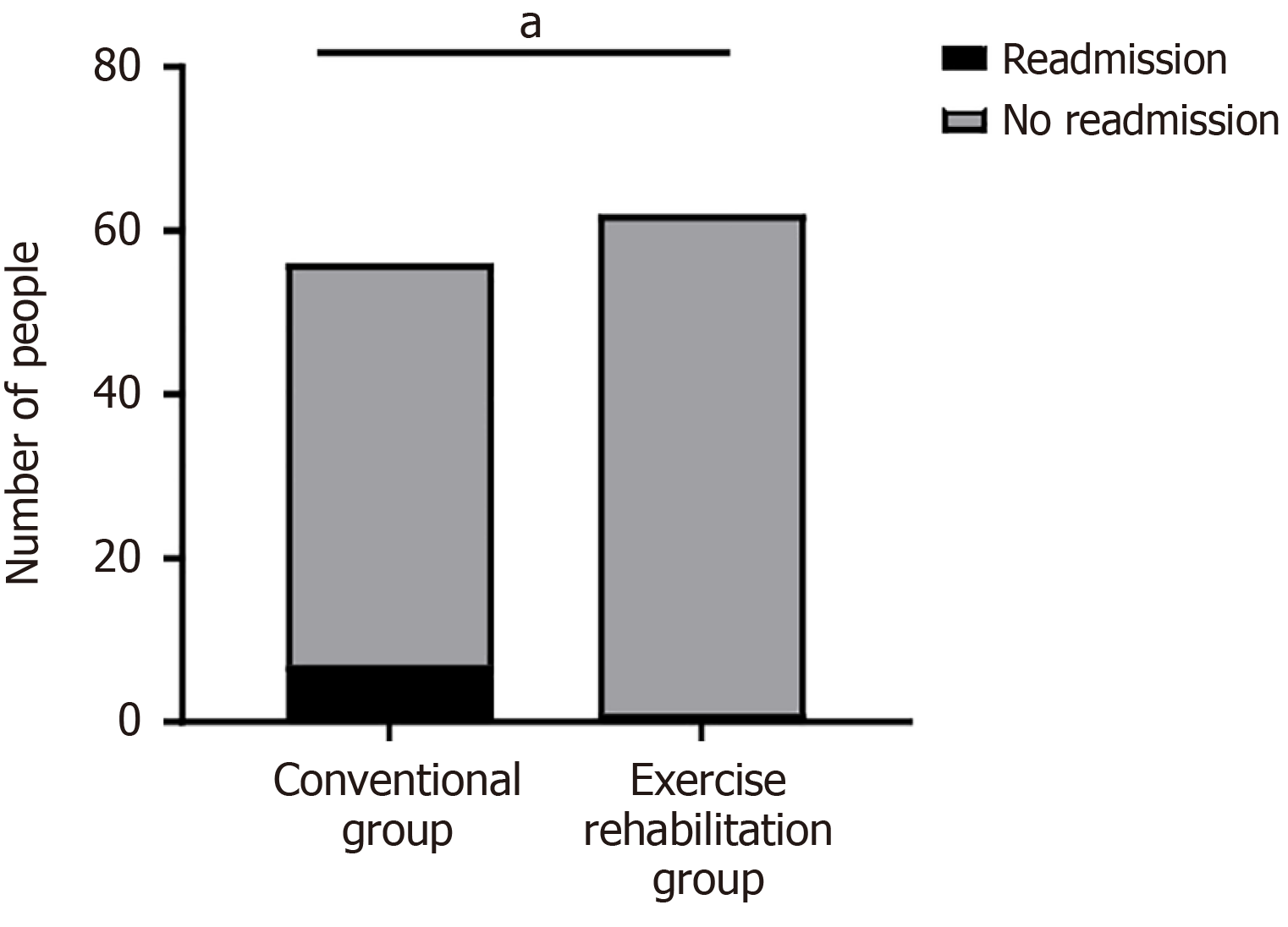

During the intervention period, a total of 8 patients were readmitted across both groups, 7 in the conventional rehabilitation group and 1 in the exercise rehabilitation group. The readmission rate was significantly lower in the exercise rehabilitation group (1.61%) than in the conventional rehabilitation group (12.50%) (χ2 = 3.930, P = 0.047) (Figure 3).

As the global population ages, CHF has become an important disease affecting the health and quality of life of older adults. CHF not only leads to a decline in cardiac function, but is often accompanied by mental and psychological problems, such as depression, anxiety, and sleep disorders. These problems further aggravate the physical and mental burden of patients and affect their rehabilitation processes and quality of life[22]. The treatment and rehabilitation needs of older patients with CHF with psychological problems are more complex, and the traditional single medical model has made it difficult to meet the needs of comprehensive rehabilitation. As an innovative chronic disease management model, medical care-family integration emphasizes patient-centeredness, closely combines medical teams with family members, and participates in the patient rehabilitation process. This concept focuses not only on the physical health of patients but also on the recovery of their mental health and social function and provides patients with comprehensive, continuous, and personalized rehabilitation services[23]. In this study, we compared conventional rehabilitation and exercise rehabilitation intervention based on the concept of medical care-family integration. The study findings showed the significant advantages of exercise rehabilitation in improving cardiac function, alleviating mental and psychological problems, and reducing readmission rates, ultimately improving patients’ quality of life.

Regarding mental and psychological problems, according to the PHQ-9, GAD-7, and AIS scores and the number distribution of participants with depression, anxiety, and sleep disorders before and after the intervention, patients in the exercise rehabilitation group showed lower distribution of depression, anxiety, and sleep disorders than those in the conventional rehabilitation group after intervention, consistent with previous reports[24]. This result not only illustrates the positive impact of exercise rehabilitation on mental and psychological problems but also further emphasizes the importance of medical care-family integration in exercise rehabilitation. From the perspective of social support theory, family involvement in medical care-family integration creates a social support network for patient rehabilitation through three dimensions: emotional support (e.g., companionship and encouragement from family members), instrumental support (e.g., disease monitoring and exercise supervision), and informational support (e.g., heart failure education)[25]. The active participation of family members alleviates patient loneliness and enhances adherence to rehabilitation programs through real-time feedback mechanisms. Additionally, in line with the “seven emotions causing disease” theory in traditional Chinese medicine, long-term depression and anxiety (classified as “worry” and “thinking”) can lead to qi and blood stagnation and obstruction of heart vessels[26]. The exercise rehabilitation model combined with psychological intervention regulates qi movement and relieves emotions, achieving a synergistic effect by integrating Chinese and Western medicine. This approach helps elderly CHF patients with mental and psychological issues better understand and manage their conditions under the guidance of the medical care-family integration concept, thereby reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety and enhancing the effectiveness of exercise rehabilitation[8]. Furthermore, improving psychological well-being helps alleviate sleep disorders, further promoting overall rehabilitation[27].

Regarding cardiac function-related indicators, improvements in the 6 MWD, LVEF, LVEDD, and NT-proBNP level were significantly better in the exercise rehabilitation group than in the conventional rehabilitation group after the intervention. This indicates that exercise rehabilitation programs based on the concept of medical care-family integration can more effectively improve the cardiac function of older patients with CHF who have mental and psychological problems, consistent with previous findings[28]. The 6 MWD test is an important indicator of exercise capacity and quality of life in patients with heart failure, and its increase indicates that the patient’s activity capacity and quality of life have improved. The increase in LVEF reflects the enhancement of heart pumping function, and the decrease in LVEDD indicates that left ventricular remodeling has improved, which is crucial for reducing the progression of heart failure and hospitalization rates. The decrease in NT-proBNP level further confirmed the improvement in cardiac function, as NT-proBNP is an important biomarker for the diagnosis and prognostic evaluation of heart failure. Therefore, its reduction is usually associated with the stability or improvement of heart failure[29]. These positive changes can be attributed to the unique advantages of exercise rehabilitation based on integration of medical care and family, which not only emphasizes the guidance and supervision of professional medical staff but also fully integrates the support and participation of the family[30]. From a mechanistic perspective, exercise rehabilitation directly slows ventricular remodeling by enhancing myocardial contractility, improving endothelial function, and promoting the formation of collateral circulation. The introduction of a family supervision mechanism reduces the risk associated with exercise and ensures the safety of rehabilitation by real-time monitoring of exercise intensity and early identification of warning symptoms. Additionally, family supervision in daily life helps patients maintain an appropriate level of activity after discharge, preventing the recurrence of unhealthy habits. This reduces the patient's cardiac burden while promoting the recovery of cardiac function, as reflected in the improvement of cardiac function-related indicators[23]. Furthermore, traditional Chinese medicine theory emphasizes the "co-cultivation of body and mind", asserting that moderate exercise can "dredge meridians and activate collaterals", in combination with emotional regulation, to achieve the effect of "comforting the body and qi, and circulating blood and vessels" [31]. The integrated approach of addressing both the body and mind may further enhance improved cardiac function.

Regarding quality of life, the scores in physical, emotional, and other fields and the MLHFQ total score were significantly lower in the exercise rehabilitation group than in the conventional rehabilitation group after intervention. This shows that the medical care-family integration-based exercise rehabilitation program can significantly improve the quality of life of older patients with CHF and psychological problems compared to conventional exercise rehabilitation, consistent with previous studies by[8]. The improved physical field may be attributed to the exercise rehabilitation program based on medical care-family integration, which emphasizes personalized, moderate-intensity exercise training. This approach aligns with the evidence-based standards outlined in the "Expert Consensus on Cardiac Rehabilitation for Chronic Heart Failure in China" and allows for precise regulation of exercise intensity through home monitoring devices, such as Bluetooth heart rate monitors[15]. Notably, this mode of exercise is consistent with the traditional Chinese medicine concept of "co-cultivation of body and spirit"-enhancing the "physical" aspect through aerobic exercise while simultaneously regulating the "spiritual" state with family emotional support, thus achieving the rehabilitation goal of "unity of form and spirit"[31]. The improvement in the emotional field may be linked to the psychological support and family involvement integrated into the program. This comprehensive support system alleviates anxiety and depression through modern cognitive behavioral interventions but also rebuilds patients' social connections through family companionship, thereby improving their emotional well-being[8]. The improvements in other fields, such as reduced social isolation and economic burden, may also result from the active participation and support of family members in the patient’s rehabilitation process under the medical care-family integration model, helping to reduce the social isolation and economic stress caused by the disease[23].

Further analysis revealed that the readmission rate was significantly lower in the exercise rehabilitation group (1.61%) than in the conventional rehabilitation group (12.50%)(χ² = 3.930, P = 0.047), consistent with the results of a previous study[28]. A reduction in the readmission rate is an important indicator of the effectiveness of heart failure management, as it reflects the stability of the patient’s condition and the effectiveness of the rehabilitation program[32]. The exercise rehabilitation program based on medical care-family integration has formed a continuous and dynamic rehabilitation management system by strengthening the patients’ self-management ability, supervision, and encouragement of family members, as well as regular follow-up and timely adjustment of rehabilitation plans by medical staff. This system effectively reduces readmission events caused by disease deterioration or improper self-management and improves the long-term quality of life of patients. Exercise rehabilitation improves cardiac function and reduces heart failure-related complications, further reducing the risk of readmission[30,33]. This study achieved some valuable results; however, it had some limitations[34]. First, the sample size of this study was relatively small, which may limit the generalizability of the results. Second, this study only observed the short-term rehabilitation effect and did not evaluate the long-term prognosis. Future research should expand the sample size and prolong the observation period to further verify the long-term effects of exercise rehabilitation programs based on medical care-family integration in older patients with CHF and mental and psychological problems. Finally, this study did not conduct an in-depth analysis of confounding factors, such as patients' living environment (e.g., family economic conditions, living space) and comorbidities (e.g., diabetes). These factors could be controlled for through stratified analysis or propensity score matching in future studies.

In conclusion, our medical care-family integration-based exercise rehabilitation program showed significant effects on older patients with CHF and psychological problems. Comprehensive medical, rehabilitation, and psychological support, as well as participation and support of family members, can significantly improve cardiac function and quality of life and reduce the degree of psychological problems and readmission rate. Future research should further explore and improve this program to provide comprehensive and effective rehabilitation services for older patients with CHF and mental and psychological problems.

| 1. | Metra M, Tomasoni D, Adamo M, Bayes-Genis A, Filippatos G, Abdelhamid M, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, Antohi L, Böhm M, Braunschweig F, Gal TB, Butler J, Cleland JGF, Cohen-Solal A, Damman K, Gustafsson F, Hill L, Jankowska EA, Lainscak M, Lund LH, McDonagh T, Mebazaa A, Moura B, Mullens W, Piepoli M, Ponikowski P, Rakisheva A, Ristic A, Savarese G, Seferovic P, Sharma R, Tocchetti CG, Yilmaz MB, Vitale C, Volterrani M, von Haehling S, Chioncel O, Coats AJS, Rosano G. Worsening of chronic heart failure: definition, epidemiology, management and prevention. A clinical consensus statement by the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail. 2023;25:776-791. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Triposkiadis F, Xanthopoulos A, Parissis J, Butler J, Farmakis D. Pathogenesis of chronic heart failure: cardiovascular aging, risk factors, comorbidities, and disease modifiers. Heart Fail Rev. 2022;27:337-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chen Y, Peng W, Pang M, Zhu B, Liu H, Hu D, Luo Y, Wang S, Wu S, He J, Yang Y, Peng D. The effects of psychiatric disorders on the risk of chronic heart failure: a univariable and multivariable Mendelian randomization study. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1306150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wilhelm EAB, Davis LL, Sharpe L, Waters S. Assess and address: Screening and management of depression in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2022;34:769-779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Xiong J, Qin J, Gong K. Association between fear of progression and sleep quality in patients with chronic heart failure: A cross-sectional study. J Adv Nurs. 2023;79:3082-3091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nichols S, McGregor G, Breckon J, Ingle L. Current Insights into Exercise-based Cardiac Rehabilitation in Patients with Coronary Heart Disease and Chronic Heart Failure. Int J Sports Med. 2021;42:19-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lödding P, Beyer S, Pökel C, Kück M, Leps C, Radziwolek L, Kerling A, Haufe S, Schulze A, Kwast S, Voß J, Kubaile C, Tegtbur U, Busse M. Adherence to long-term telemonitoring-supported physical activity in patients with chronic heart failure. Sci Rep. 2024;14:22037. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Xia L. The Effects of Continuous Care Model of Information-Based Hospital-Family Integration on Colostomy Patients: a Randomized Controlled Trial. J Cancer Educ. 2020;35:301-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Jibb LA, Chartrand J, Masama T, Johnston DL. Home-Based Pediatric Cancer Care: Perspectives and Improvement Suggestions From Children, Family Caregivers, and Clinicians. JCO Oncol Pract. 2021;17:e827-e839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cuomo G, Di Lorenzo A, Tramontano A, Iannone FP, D'Angelo A, Pezzella R, Testa C, Parlato A, Merone P, Pacileo M, D'Andrea A, Cudemo G, Venturini E, Iannuzzo G, Vigorito C, Giallauria F. Exercise Training in Patients with Heart Failure: From Pathophysiology to Exercise Prescription. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2022;23:144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chinese Society of Cardiology; Chinese Medical Association; Chinese College of Cardiovascular Physician; Chinese Heart Failure Association of Chinese Medical Doctor Association; Editorial Board of Chinese Journal of Cardiology. [Chinese guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of heart failure 2024]. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2024;52:235-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Costantini L, Pasquarella C, Odone A, Colucci ME, Costanza A, Serafini G, Aguglia A, Belvederi Murri M, Brakoulias V, Amore M, Ghaemi SN, Amerio A. Screening for depression in primary care with Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9): A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2021;279:473-483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 413] [Cited by in RCA: 352] [Article Influence: 88.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Locke AB, Kirst N, Shultz CG. Diagnosis and management of generalized anxiety disorder and panic disorder in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91:617-624. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Zhang X, Lin JL, Gao R, Chen N, Huang GF, Wang L, Gao H, Zhuo HZ, Chen LQ, Chen XH, Li H. Application of the hospital-family holistic care model in caregivers of patients with permanent enterostomy: A randomized controlled trial. J Adv Nurs. 2021;77:2033-2049. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Professional Committee of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation of Chinese Rehabilitation Medical Association. [Expert consensus on cardiac rehabilitation for chronic heart failure in China]. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 2020;59:942-952. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lu D, Cheng CY, Zhu XJ, Li JY, Zhu YJ, Zhou YP, Qiu LH, Cheng WS, Li XM, Mei KY, Wang DL, Zhao ZY, Wang PW, Zhang SX, Chen YH, Chen LF, Sun K, Jing ZC. Heart Rate Response Predicts 6-Minutes Walking Distance in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 2023;204:207-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Rector TS, Cohn JN. Assessment of patient outcome with the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure questionnaire: reliability and validity during a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of pimobendan. Pimobendan Multicenter Research Group. Am Heart J. 1992;124:1017-1025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 689] [Cited by in RCA: 710] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Dunderdale K, Thompson DR, Beer SF, Furze G, Miles JN. Development and validation of a patient-centered health-related quality-of-life measure: the chronic heart failure assessment tool. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2008;23:364-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hammash MH, Hall LA, Lennie TA, Heo S, Chung ML, Lee KS, Moser DK. Psychometrics of the PHQ-9 as a measure of depressive symptoms in patients with heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2013;12:446-453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Liu M, Wang D, Fang J, Chang Y, Hu Y, Huang K. Validation of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 in patients with COPD: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23:593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Soldatos CR, Dikeos DG, Paparrigopoulos TJ. Athens Insomnia Scale: validation of an instrument based on ICD-10 criteria. J Psychosom Res. 2000;48:555-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 809] [Cited by in RCA: 1056] [Article Influence: 42.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Abou Kamar S, Oostdijk B, Andrzejczyk K, Constantinescu A, Caliskan K, Akkerhuis KM, Umans V, Brugts JJ, Boersma E, van Dalen B, Kardys I. Temporal evolution of anxiety and depression in chronic heart failure and its association with clinical outcome. Int J Cardiol. 2024;411:132274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Yu H, Guo H. Effects of hospital-family holistic care mode on psychological state and nutritional status of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Transl Res. 2023;15:6760-6770. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Li LP, Rao DF, Chen XX, Qi XY, Chen XX, Wang XQ, Li J. The impact of hospital-family integrated continuation nursing based on information technology on patients unhealthy mood, family function and sexual function after cervical cancer surgery. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023;102:e33504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Liu C, Chen H, Zhou F, Long Q, Wu K, Lo LM, Hung TH, Liu CY, Chiou WK. Positive intervention effect of mobile health application based on mindfulness and social support theory on postpartum depression symptoms of puerperae. BMC Womens Health. 2022;22:413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Liu XM, Liu HM, Ma LL, Zhang DK, Ma HY, Lin JZ, Xu RC. [Correlation between internal damage due to seven emotions in traditional Chinese medicine and pathogenesis of breast cancer from perspective of psychological stress]. Zhongguo Zhong Yao Za Zhi. 2021;46:6377-6386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Redeker NS, Yaggi HK, Jacoby D, Hollenbeak CS, Breazeale S, Conley S, Hwang Y, Iennaco J, Linsky S, Nwanaji-Enwerem U, O'Connell M, Jeon S. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia has sustained effects on insomnia, fatigue, and function among people with chronic heart failure and insomnia: the HeartSleep Study. Sleep. 2022;45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Chen YW, Wang CY, Lai YH, Liao YC, Wen YK, Chang ST, Huang JL, Wu TJ. Home-based cardiac rehabilitation improves quality of life, aerobic capacity, and readmission rates in patients with chronic heart failure. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e9629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Peng X, Su Y, Hu Z, Sun X, Li X, Dolansky MA, Qu M, Hu X. Home-based telehealth exercise training program in Chinese patients with heart failure: A randomized controlled trial. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e12069. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Lu L, Wei S, Huang Q, Chen Y, Huang F, Ma X, Huang C. Effect of "Internet + tertiary hospital-primary hospital-family linkage home care" model on self-care ability and quality of life of discharged stroke patients. Am J Transl Res. 2023;15:6727-6739. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Shen H, Lian A, Wu Y, Zhou J, Liu Y, Zhu L, Zhang Y, Yi Z, Liu X, Fan Q. Shen-based Qigong Exercise improves cognitive impairment in stable schizophrenia patients in rehabilitation wards: a randomized controlled study. BMC Psychiatry. 2024;24:796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Meng Y, Zhuge W, Huang H, Zhang T, Ge X. The effects of early exercise on cardiac rehabilitation-related outcome in acute heart failure patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2022;130:104237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Achttien RJ, Staal JB, van der Voort S, Kemps HM, Koers H, Jongert MW, Hendriks EJ; Practice Recommendations Development Group. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation in patients with chronic heart failure: a Dutch practice guideline. Neth Heart J. 2015;23:6-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Wu L, Lin Y, Xue R, Guo B, Bai J. The effects of continuous nursing via the WeChat platform on neonates after enterostomy: a single-centre retrospective cohort study. BMC Nurs. 2023;22:13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |