Published online Jun 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i6.103270

Revised: January 22, 2025

Accepted: April 17, 2025

Published online: June 19, 2025

Processing time: 174 Days and 23.9 Hours

Psychological interventions have demonstrated efficacy in improving patients’ emotional state, cognition, and thinking abilities, thereby enhancing their quality of life and survival. This review examines literature from the China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Wanfang Data, Web of Science, and PubMed databases published over the past decade, focusing on the use of psychotherapy for post-stroke anxiety and depression. The prevalence of anxiety and depression is signi

Core Tip: The prevalence of anxiety and depression is significantly higher among patients who have experienced a stroke than in the general population, possibly due to vestibular dysfunction following brain injury. Psychological interventions, including cognitive behavioral therapy, supportive psychotherapy, music and art therapy, and exercise therapy, effectively alleviate post-stroke anxiety and depression, promoting patients’ emotional well-being and physical rehabilitation.

- Citation: Lei XY, Chen LH, Qian LQ, Lu XD. Psychological interventions for post-stroke anxiety and depression: Current approaches and future perspectives. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(6): 103270

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i6/103270.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i6.103270

Stroke is a severe neurological disorder with profound effects on the physical, cognitive, and emotional well-being[1]. The prevalence of anxiety and depression is significantly higher in stroke patients than in the general population, affecting their quality of life and rehabilitation outcomes[2]. Vestibular dysfunction following a stroke can lead to symptoms such as vertigo, balance disorders, nystagmus, nausea, and vomiting. The vestibular system, which play a crucial role in maintaining balance and spatial orientation, becomes compromised, leading to these impairments. The discomfort and functional limitations caused by dizziness can adversely impact psychological well-being, often resulting in anxiety and depression. These psychological issues can, in turn, create a vicious cycle by intensifying vertigo symptoms and exacerbating the overall distress and impairment experienced by the patients[3,4]. However, the causal mechanisms linking post-stroke vertigo to post-stroke depression (PSD) and post-stroke anxiety (PSA) remain unclear. Establishing these causal relationships could inform targeted therapeutic interventions[5]. In recent years, psychological interventions for PSA and PSD have become a focus of research. This review summarizes current knowledge in this area.

The mechanisms underlying PSA and PSD are complex and involve physiological, psychological, and social factors[6]. The incidence of anxiety and depression in stroke patients can reach 30%-50%[7]. Crocker et al[8] were the first to report emotional dysregulation in patients with subacute and chronic stroke, with a prevalence of anxiety and irritability ranging from 15% to 34%. Taylor-Rowan et al[9] found that 15.1% of stroke patients exhibited post-stroke anger upon admission (Figure 1). In a recent study of 25488 patients, 31% experienced depression within 5 years after stroke, with a cumulative prevalence of one or more depressive episodes ranging from 39% to 52%[10]. A study by Yin et al[11] of 153 stroke patients found that 49.1% had depressive symptoms. Mood disorders not only impede the rehabilitation process but are also associated with high mortality rates. Therefore, timely and effective psychological intervention is crucial. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have indicated that psychological interventions significantly reduce PSA and PSD[12]. Moreover, individualized psychological intervention plans have been shown to be more effective than standardized approaches in meeting patients’ needs and improving treatment outcomes[13].

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a widely used psychological intervention for anxiety and depression[14]. CBT helps patients with stroke identify and alter negative thought patterns, thereby reducing anxiety and depression[15,16]. Activities include body scanning, mindful breathing exercises, awareness of inner thoughts, focusing on current emotions, mindful stretching, and nature meditation, all of which help alleviate anxiety and depression, enhance memory and executive function, and significantly improve quality of life. This therapy is widely applicable to patients with a range of psychological health conditions, including depression, anxiety disorders, eating disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorders, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Its effectiveness lies in modifying the patient’s perceptions and response patterns to specific situations, thereby alleviating negative emotions and enhancing quality of life. The therapy requires skilled psychologists for administration, involves a relatively long duration, and depends on the patient’s active participation and cooperation.

Supportive psychotherapy focuses on providing emotional support and building a strong therapist-patient relationship. This approach effectively reduces anxiety and depression in patients with stroke by providing a safe environment for expressing emotions[17-19]. This therapy is particularly suitable for patients in need of emotional support and psychological comfort, especially those who have experienced significant life events or psychological trauma. It assists patients in managing difficulties and challenges, while enhancing their coping abilities. The implementation of this therapy is relatively straightforward; however, its clinical effectiveness relies heavily on the therapist’s professional competence and the patient’s active participation.

In recent years, music and art therapy have attracted attention as non-traditional psychological interventions. These therapies help stroke patients reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression by encouraging emotional expression and social interaction. Music and art therapy utilize various forms including painting, music, dance, and writing, to facilitate emotional expression and significantly improve psychological well-being. Music therapy, in particular, can directly stimulate the hypothalamus and limbic system through sound frequencies, which plays a crucial role in emotion regulation, thereby exerting a bidirectional regulatory effect. Soothing music activates the brain’s emotional processing areas, inducing feelings of happiness and pleasure, which helps alleviate psychological stress and diminish negative emotions such as anxiety and depression[20]. These approaches are primarily suited for patients who prefer to express their emotions through art and relieve stress, including those with conditions like schizophrenia or autism. They require guidance from professional music and art therapists, and their effectiveness may vary from person to person.

Moderate physical activity is beneficial for mental health. Exercise promotes the release of neurotransmitters such as endorphins in the brain, which have analgesic and mood-enhancing effects, helping to alleviate symptoms of anxiety and depression. Simultaneously, exercise can regulate the availability of neurotransmitters, such as serotonin and norepinephrine, further contributing to mood improvement. Clinical evidence indicates that aerobic exercises, such as running, swimming, and cycling, can serve as adjunctive treatments for patients with mild-to-moderate anxiety and depression. Therefore, the combination of exercise with psychological interventions may be an effective treatment approach[21]. This therapy is suitable for patients who wish to improve their mental health through physical activity, such as those with hyperlipidemia or peripheral nerve injuries. Its implementation is relatively simple but requires the development of a professional exercise plan, and safety precautions should be taken during the exercise.

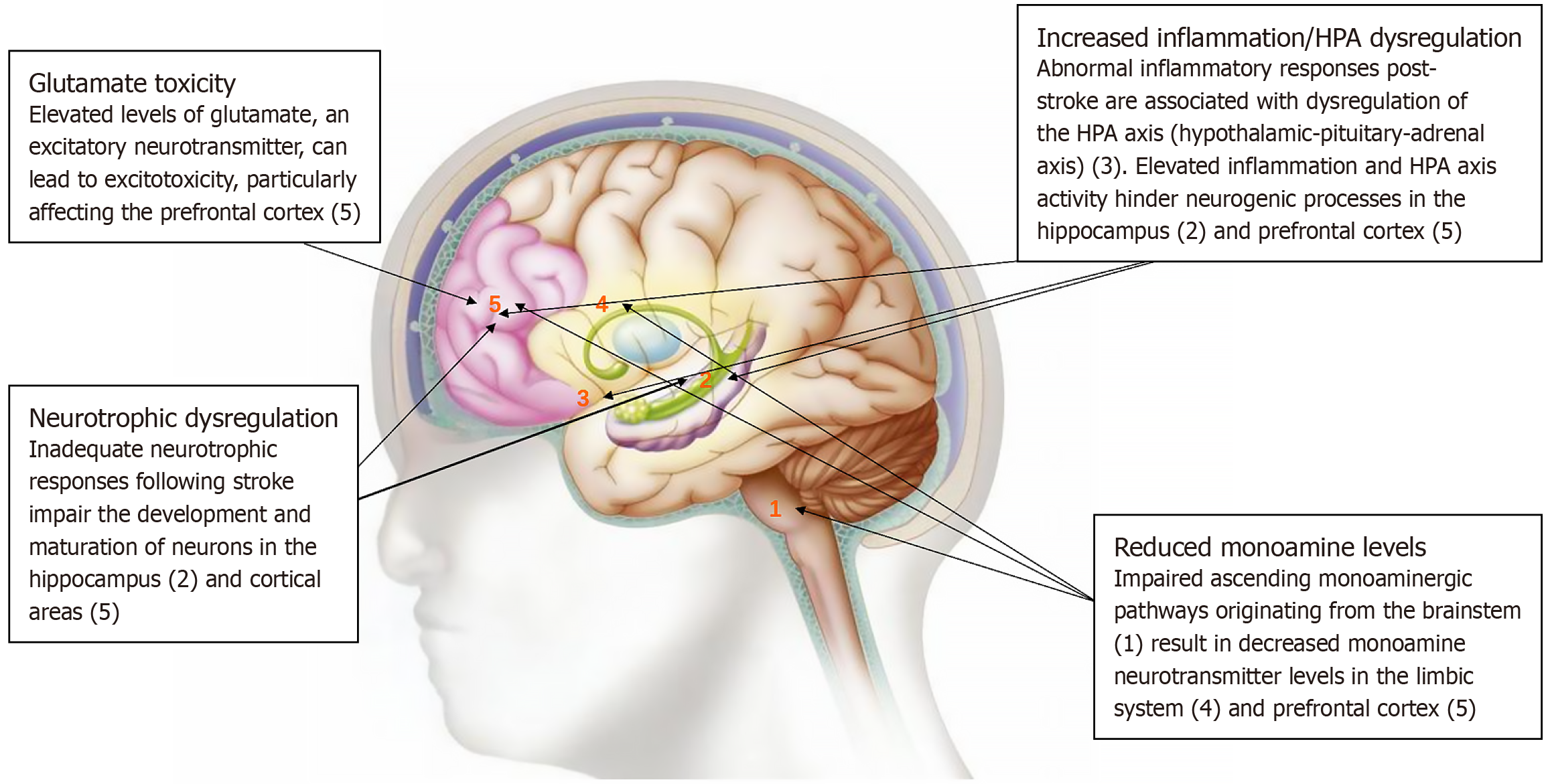

PSD is a common psychological disorder associated with higher mortality, poorer recovery, more pronounced cognitive deficits, and a lower quality of life than stroke patients without depression[22]. The pathophysiology of PSD is multifactorial and involves reduced monoamine levels, abnormal neurotrophic responses, dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, and glutamate-mediated excitotoxicity[23-25]. Medeiros et al[26] estimated the prevalence of PSD to be between 18% and 33%, highlighting the inadequacy of current diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. Risk factors for PSD include female sex, psychiatric history, extensive or multiple strokes, frontal/anterior or basal ganglia lesions, stroke within the past year, poor social support, and significant disability[27]. Identifying these risk factors can guide clinicians in closely monitoring depressive symptoms and implementing preventive interventions. The clinical risk factors for PSD can be categorized into three groups: Pre-stroke, stroke-related, and post-stroke (Table 1)[27-29].

| Classification | Factors |

| Pre-stroke risk factors gender | Female |

| Personal history of mental disorders, specifically depression | |

| Family history of mental disorders | |

| Elevated neuroticism | |

| Stroke-associated risk factors | Extensive and multiple strokes |

| Frontal or anterior brain strokes | |

| Basal ganglia strokes | |

| Post-stroke risk factors | First year post-stroke |

| High degree of disability | |

| Reduced independence | |

| Diffuse white matter injury | |

| Social isolation |

Psychosocial interventions are considered effective in the treatment of PSD. A randomized controlled trial compared the outcomes of antidepressant therapy alone with those of antidepressant therapy combined with an 8-week nurse-led “psychosocial behavioral intervention”, including education and nursing support. The combined intervention group showed significantly higher remission rates both post-intervention and at 12-month follow-up[30]. Wang et al[31] conducted a meta-analysis of 23 studies, finding that CBT alone [standardized mean difference = -0.76; 95% confidence interval (CI): -1.22 to -0.29; P = 0.001] and CBT combined with antidepressants (standardized mean difference = -0.95; 95%CI: -1.20 to -0.71; P < 0.001) effectively alleviated depressive symptoms in PSD patients. The objectives of CBT include modifying cognitive distortion, developing coping skills, engaging patients in activities that promote symptom relief, and improving emotional regulation[32,33]. Several randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that CBT significantly enhances the psychological health of patients with stroke[34]. Two such trials have reported a notable reduction in depressive symptoms after CBT. Yang et al[35] summarized in their review that mindfulness training could serve as a universal approach to alleviate psychological distress and improve emotional states in patients. Wan et al[36] found that CBT might help reduce the severity of depression and enhance the quality of life, although cognitive function might remain unaffected. An analysis of 432 patients undergoing CBT and 385 control patients indicated significant improvements in depressive symptoms and quality of life post-stroke; however, no significant differences in cognitive function were observed between the groups. In a controlled trial involving 58 patients with PSD, Han et al[37] reported that CBT enhances mood, functional abilities, and self-management skills. The therapy improved the patients’ cognitive processes and alleviated negative behaviors and emotions through rational dialogue and relaxation exercises.

In a study of 529 elderly patients aged 60 and above, exercise therapy was found to significantly lower the risk of depression in post-stroke patients[38]. In particular, Tai Chi practice demonstrated a negative correlation between exercise duration and risk of depression, with long-term engagement reducing the likelihood of depressive symptoms. Li et al[39] observed that 25 patients who engaged in a 6-week aerobic exercise regimen (e.g., cycling, yoga, and brisk walking) showed significant improvements in depressive states and enhanced antioxidant capacity. In another controlled study, Du et al[40] employed a combination of music and exercise therapy. The exercise routine was consistent with that of the control group, but music interventions were incorporated during the sessions, featuring calming pieces such as Yun Shui Chan Xin, Guangling San, and Gao Shan Liu Shui. The results indicated that the music-enhanced therapy group exhibited significant improvement in depressive symptoms. Music therapy can stimulate the limbic and reticular activation systems of the brain, influencing psychological states through auditory processing centers in the cerebral cortex. It promotes endorphin release, suppresses hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing hormone, and reduces sympathetic nervous system activity, thereby alleviating anxiety and depressive emotions and fostering relaxation and a positive mood[41].

PSA is characterized by excessive worry, fear, irritability, and insomnia following a stroke[42]. Anxiety can occur at different stages of stroke. The incidence of PSA ranges from 19.3% to 30.8% in China. A meta-analysis of studies published worldwide reported a PSA prevalence of 18%-36.7%[43]. In another meta-analysis, Rafsten et al[44] found that the overall prevalence of anxiety within the first year after stroke was 29.3% (95%CI: 24.8%-33.8%). The incidence was highest within the first 2 weeks after stroke (36.7%), decreasing to 24.1% 2 weeks to 3 months after stroke, and 23.8% 3-12 months after stroke. However, these estimates exhibited significant heterogeneity (I² = 97%; P < 0.001). The neurobiological mechanisms underlying PSA remain poorly understood, with most insights derived from PSD research[45]. Younger age is a significant predictor of PSA, with higher anxiety levels often observed in younger patients who may face greater family and social responsibilities[46]. Many stroke survivors experience neurological deficits, reduced physical functioning, decreased social engagement, and limited participation, all of which contribute to the feelings of loss, helplessness, and irritability. Ayasrah et al[47] reported that 45.6% of 226 patients with stroke exhibited clinically significant anxiety levels associated with challenges in self-care, insufficient income, and vision problems following stroke. To achieve high-quality recovery and improved survival, patients with stroke require pharmacological treatment, emotional stability, and cognitive support.

Psychological support therapy involves addressing patients’ psychological issues, along with routine treatment, dietary guidance, and medication. Love et al[48] found that meditation training enhanced patients’ resilience, reduced their anxiety levels, and improved their stress management abilities. Using paired sample t-tests, they assessed the effect of meditation on the recovery of stroke survivors in the intervention group (n = 20), with evaluations conducted at baseline and after four weeks of intervention. These findings indicate that incorporating mindfulness training into CBT facilitates stress perception, reduces anxiety, and enhances coping capacity. Mi et al[49] conducted a randomized controlled trial in 94 stroke patients using psychological interventions such as distraction and verbal counseling. Compared to the control group, participants in the intervention group showed a significant reduction in negative emotions. Overall, psychological interventions played a positive role in alleviating PSA levels, significantly enhancing recovery, and improving functioning and quality of life.

Although psychological interventions have demonstrated significant therapeutic effects in the treatment of PSA and PSD, several challenges remain. Cognitive functioning is a critical factor that influences the effectiveness of psychological interventions. Psychotherapy is difficult to implement in patients with severe cognitive impairment. Second, professional psychological counselors and therapists are essential to effectively administer these interventions. However, there is a shortage of such professionals in China. Furthermore, the cost of psychotherapy is relatively high, imposing an economic burden on patients and their families.

Research into psychological interventions for PSA and PSD is expected to increase as neuroscience, psychology, and rehabilitation medicine continue to develop. Existing therapies have shown promising results; however, further large-scale randomized controlled trials are necessary to validate the effectiveness and applicability of different psychological interventions. Future research should investigate the integration of psychotherapy with pharmacological treatments to achieve more comprehensive therapeutic outcomes. In summary, psychological interventions for PSA and PSD are important to improve patients’ quality of life and promote recovery. Continued research in this field can advance our understanding and contribute to the development of improved treatment strategies.

| 1. | Zhao Y, Zhang X, Chen X, Wei Y. Neuronal injuries in cerebral infarction and ischemic stroke: From mechanisms to treatment (Review). Int J Mol Med. 2022;49:15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 257] [Article Influence: 64.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Pohl M, Hesszenberger D, Kapus K, Meszaros J, Feher A, Varadi I, Pusch G, Fejes E, Tibold A, Feher G. Ischemic stroke mimics: A comprehensive review. J Clin Neurosci. 2021;93:174-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Li S, Jia Z, Zhang Z, Li Y, Ding Y, Qin Z, Guo S. Effect of gender on the association between cumulative cardiovascular risk factors and depression: results from the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Gen Psychiatr. 2023;36:e101063. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ju P, Zhao D, Ma L, Chen J. Biomarker development perspective: Exploring comorbid chronic pain in depression through deep transcranial magnetic stimulation. J Transl Int Med. 2024;12:123-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tater P, Pandey S. Post-stroke Movement Disorders: Clinical Spectrum, Pathogenesis, and Management. Neurol India. 2021;69:272-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Einstad MS, Saltvedt I, Lydersen S, Ursin MH, Munthe-Kaas R, Ihle-Hansen H, Knapskog AB, Askim T, Beyer MK, Næss H, Seljeseth YM, Ellekjær H, Thingstad P. Associations between post-stroke motor and cognitive function: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21:103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Galovic M, Ferreira-Atuesta C, Abraira L, Döhler N, Sinka L, Brigo F, Bentes C, Zelano J, Koepp MJ. Seizures and Epilepsy After Stroke: Epidemiology, Biomarkers and Management. Drugs Aging. 2021;38:285-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 22.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Crocker TF, Brown L, Lam N, Wray F, Knapp P, Forster A. Information provision for stroke survivors and their carers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;11:CD001919. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Taylor-Rowan M, Momoh O, Ayerbe L, Evans JJ, Stott DJ, Quinn TJ. Prevalence of pre-stroke depression and its association with post-stroke depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2019;49:685-696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Salinas J, Sprinkhuizen SM, Ackerson T, Bernhardt J, Davie C, George MG, Gething S, Kelly AG, Lindsay P, Liu L, Martins SC, Morgan L, Norrving B, Ribbers GM, Silver FL, Smith EE, Williams LS, Schwamm LH. An International Standard Set of Patient-Centered Outcome Measures After Stroke. Stroke. 2016;47:180-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Yin XF, Hu CW, Qi QY, Li XQ. [Mental health survey of elderly patients with post-stroke depression in a community]. Zhongguo Yiyao Zhinan. 2015;60-61. |

| 12. | Kapoor A, Lanctôt KL, Bayley M, Kiss A, Herrmann N, Murray BJ, Swartz RH. "Good Outcome" Isn't Good Enough: Cognitive Impairment, Depressive Symptoms, and Social Restrictions in Physically Recovered Stroke Patients. Stroke. 2017;48:1688-1690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Powell MP, Verma N, Sorensen E, Carranza E, Boos A, Fields DP, Roy S, Ensel S, Barra B, Balzer J, Goldsmith J, Friedlander RM, Wittenberg GF, Fisher LE, Krakauer JW, Gerszten PC, Pirondini E, Weber DJ, Capogrosso M. Epidural stimulation of the cervical spinal cord for post-stroke upper-limb paresis. Nat Med. 2023;29:689-699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 43.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kendall PC, Maxwell CA, Jakubovic RJ, Ney JS, McKnight DS, Baker S. CBT for Youth Anxiety: How Does It Fit Within Community Mental Health? Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2023;25:13-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | van Loenen I, Scholten W, Muntingh A, Smit J, Batelaan N. The Effectiveness of Virtual Reality Exposure-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Severe Anxiety Disorders, Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, and Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24:e26736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Yarwood B, Taylor R, Angelakis I. User Experiences of CBT for Anxiety and Depression: A Qualitative Systematic Review and Meta-synthesis. Community Ment Health J. 2024;60:662-671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Markowitz JC. Supportive Evidence: Brief Supportive Psychotherapy as Active Control and Clinical Intervention. Am J Psychother. 2022;75:122-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Miklowitz DJ, Efthimiou O, Furukawa TA, Scott J, McLaren R, Geddes JR, Cipriani A. Adjunctive Psychotherapy for Bipolar Disorder: A Systematic Review and Component Network Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:141-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 31.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Shatri H, Alwi I, Ismail RI, Herqutanto H, Yuniarti KW, Soewondo P, Rengganis I, Harimurti K, Putranto R, Abdullah V, Lukman PR, Elvira SD, Suwarto S. Supportive Psychotherapy for Healthcare Professionals in The Management of Acute Coronary Syndrome: The Use of Delphi Technique. Acta Med Indones. 2022;54:218-237. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Bleibel M, El Cheikh A, Sadier NS, Abou-Abbas L. The effect of music therapy on cognitive functions in patients with Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2023;15:65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ströhle A. Sports psychiatry: mental health and mental disorders in athletes and exercise treatment of mental disorders. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2019;269:485-498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lam Ching W, Li HJ, Guo J, Yao L, Chau J, Lo S, Yuen CS, Ng BFL, Chau-Leung Yu E, Bian Z, Lau AY, Zhong LL. Acupuncture for post-stroke depression: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23:314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Yue Y, You L, Zhao F, Zhang K, Shi Y, Tang H, Lu J, Li S, Cao J, Geng D, Wu A, Yuan Y. Common susceptibility variants of KDR and IGF-1R are associated with poststroke depression in the Chinese population. Gen Psychiatr. 2023;36:e100928. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Fan Y, Wang L, Jiang H, Fu Y, Ma Z, Wu X, Wang Y, Song Y, Fan F, Lv Y. Depression circuit adaptation in post-stroke depression. J Affect Disord. 2023;336:52-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ashaie SA, Funkhouser CJ, Jabbarinejad R, Cherney LR, Shankman SA. Longitudinal Trajectories of Post-Stroke Depression Symptom Subgroups. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2023;37:46-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Medeiros GC, Roy D, Kontos N, Beach SR. Post-stroke depression: A 2020 updated review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2020;66:70-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 300] [Article Influence: 60.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Blake JJ, Gracey F, Whitmore S, Broomfield NM. Comparing the Symptomatology of Post-stroke Depression with Depression in the General Population: A Systematic Review. Neuropsychol Rev. 2024;34:768-790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Kaadan MI, Larson MJ. Management of post-stroke depression in the Middle East and North Africa: Too little is known. J Neurol Sci. 2017;378:220-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Yang Z, Jiang Y, Xiao Y, Qian L, Jiang Y, Hu Y, Liu X. Di-Huang-Yin-Zi regulates P53/SLC7A11 signaling pathway to improve the mechanism of post-stroke depression. J Ethnopharmacol. 2024;319:117226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Swartz RH, Bayley M, Lanctôt KL, Murray BJ, Cayley ML, Lien K, Sicard MN, Thorpe KE, Dowlatshahi D, Mandzia JL, Casaubon LK, Saposnik G, Perez Y, Sahlas DJ, Herrmann N. Post-stroke depression, obstructive sleep apnea, and cognitive impairment: Rationale for, and barriers to, routine screening. Int J Stroke. 2016;11:509-518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Wang SB, Wang YY, Zhang QE, Wu SL, Ng CH, Ungvari GS, Chen L, Wang CX, Jia FJ, Xiang YT. Cognitive behavioral therapy for post-stroke depression: A meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2018;235:589-596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Liao W, Chen D, Wu J, Liu K, Feng J, Li H, Jiang J. Risk factors for post-stroke depression in patients with mild and moderate strokes. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023;102:e34157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Pan C, Li G, Sun W, Miao J, Wang Y, Lan Y, Qiu X, Zhao X, Wang H, Zhu Z, Zhu S. Psychopathological network for early-onset post-stroke depression symptoms. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23:114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Hama S, Yamashita H, Yamawaki S, Kurisu K. Post-stroke depression and apathy: Interactions between functional recovery, lesion location, and emotional response. Psychogeriatrics. 2011;11:68-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Yang NN, Lin LL, Li YJ, Li HP, Cao Y, Tan CX, Hao XW, Ma SM, Wang L, Liu CZ. Potential Mechanisms and Clinical Effectiveness of Acupuncture in Depression. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2022;20:738-750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Wan M, Zhang Y, Wu Y, Ma X. Cognitive behavioural therapy for depression, quality of life, and cognitive function in the post-stroke period: systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychogeriatrics. 2024;24:983-992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Han H, Zhou Y, Zhang XL, Wang FL, Shao T, Xing FM. [The effect of cognitive-behavioral therapy on depression and self-management behavior in post-stroke patients]. Shandong Yiyao. 2015;55:36-38. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 38. | Li XX, Qiang XX, Gao XX. [Efficacy of Sanyinjiao warm acupuncture combined with exercise therapy on post-stroke depression patients]. Guoji Yiyao Weisheng Daobao. 2024;30:1693-1697. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 39. | Li XY, Wu MM, Zhu LW. [The role of exercise therapy in regulating the "brain-gut axis" in the treatment of post-stroke depression: A review of the research progress]. Shandong Yiyao. 2024;64:89-92. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 40. | Du ZF, Liu YR, Yang Y, Wang WL, Li T. [Effect of music combined with exercise therapy on motor function and negative emotions in stroke patients]. Guoji Jingshenbingxue Zazhi. 2022;49:1059-1062. |

| 41. | Zhao QY, Lin Q, Cheng K, Li XP. [The effects of music-exercise therapy on motor function, walking ability, and mental health in stroke patients]. Zhongguo Kangfu Yixue Zazhi. 2017;32:293-296. |

| 42. | Frank D, Gruenbaum BF, Zlotnik A, Semyonov M, Frenkel A, Boyko M. Pathophysiology and Current Drug Treatments for Post-Stroke Depression: A Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:15114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Ignacio KHD, Muir RT, Diestro JDB, Singh N, Yu MHLL, Omari OE, Abdalrahman R, Barker-Collo SL, Hackett ML, Dukelow SP, Almekhlafi MA. Prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms after stroke in young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2024;33:107732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Rafsten L, Danielsson A, Sunnerhagen KS. Anxiety after stroke: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Rehabil Med. 2018;50:769-778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 22.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Baylan S, Griffiths S, Grant N, Broomfield NM, Evans JJ, Gardani M. Incidence and prevalence of post-stroke insomnia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2020;49:101222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 23.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Almhdawi KA, Alazrai A, Kanaan S, Shyyab AA, Oteir AO, Mansour ZM, Jaber H. Post-stroke depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms and their associated factors: A cross-sectional study. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2021;31:1091-1104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Ayasrah S, Ahmad M, Basheti I, Abu-Snieneh HM, Al-Hamdan Z. Post-stroke Anxiety Among Patients in Jordan: A Multihospital Study. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2022;35:705-716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Love MF, Sharrief A, LoBiondo-Wood G, Cron SG, Sanner Beauchamp JE. The Effects of Meditation, Race, and Anxiety on Stroke Survivor Resilience. J Neurosci Nurs. 2020;52:96-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Mi L, Meng L, Li PP. [The application of psychological intervention combined with rehabilitation nursing in patients with sequelae of cerebral apoplexy]. Xinli Yuekan. 2021;16:158-160. [DOI] [Full Text] |