Published online Sep 9, 2025. doi: 10.5409/wjcp.v14.i3.107165

Revised: April 10, 2025

Accepted: May 7, 2025

Published online: September 9, 2025

Processing time: 91 Days and 15.8 Hours

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a group of chronic disorders that cause relapsing inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT). It results either from gene-environment interactions or as a monogenic disease resulting from pa

Core Tip: Monogenic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is an evolving entity in pe

- Citation: Ghosh U, Samanta A. Monogenic inflammatory bowel disease: An unfolding enigma. World J Clin Pediatr 2025; 14(3): 107165

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2219-2808/full/v14/i3/107165.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5409/wjcp.v14.i3.107165

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a complex disease process characterized by chronic inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT). It results either from gene-environment interactions or as a monogenic disease resulting from pathogenic mutations causing impairment in the protective mechanism of the GIT[1]. Around 10%-15% of patients with very early onset IBDs (VEO-IBD), defined as IBD presenting before 6 years of age, may have an underlying monogenic condition[2-4]. Monogenic IBD differs from polygenic IBD in its pathogenesis; the underlying genetic mutations in monogenic IBD lead to uncontrolled intestinal inflammation. It is a common cause of infantile-onset IBD, it is more commonly associated with various extraintestinal comorbidities and responds poorly to conventional treatment modalities[5]. An in-depth understanding of this distinct form of IBD is essential for deciding the appropriate therapeutic approach as well as disease prognostication. This review focuses on the epidemiology, clinical presentation, diagnostic approach and therapeutic challenges in patients with monogenic IBD.

With the greater use of next generation sequencing (NGS), more cases of monogenic IBD are being diagnosed. Molecular diagnosis of monogenic IBD is essential to determine the correct prognosis and treatment strategy which differs from polygenic IBD. While many cases of monogenic IBD respond to biological therapy, some disorders like interleukin (IL)-10 signaling defects, immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked (IPEX) syndrome, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome (WAS), or X-linked inhibitors of apoptosis (XIAP) deficiency, benefit from hematopoietic stem cell tra

Pediatric IBD accounts for 20%–25% of patients with IBD. Infantile-onset IBD is defined as those having onset of IBD at less than 2 years of age, while VEO-IBD is defined as those with disease-onset before 6 years of age[10]. Infantile-onset IBD has been reported in approximately 1%, and VEO-IBD in about 15% of pediatric IBD patients[11]. In a single centre large cohort of 1005 pediatric IBD patients, where whole exome sequencing (WES) was performed for all patients, monogenic IBD constituted 3% of all cases and 7.8% of VEO-IBD[12]. In various paediatric studies, the proportion of monogenic IBD ranged between 0%-33% and 13%-41% among VEO-IBD and infantile-onset IBD patients respectively[10]. The incidence of monogenic IBD is rising, may be due to increasing awareness and advances in genetic testing[10,13,14]. The European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) 2021 position statement on the diagnosis of monogenic IBD identified 75 genes, and a recent study which aimed to establish a multidimensional taxonomy for monogenic IBD has identified 102 pathogenic genes[10,15]. In a systematic review of 750 monogenic IBD cases, the most commonly affected genes were IL-10RA/B, XIAP, CYBB [chronic granulomatous disease (CGD)], LRBA and tetratricopeptide repeat domain 7A (TTC7A)[5].

Monogenic IBD is classified into 6 classes, based on the defect in the immune mechanisms: (1) Dysfunction of neutrophils and granulocytes; (2) Hyper and autoinflammatory disorders; (3) Complex defects in T cells and B cells function; (4) Defects in regulatory T cells and IL-10 signaling; (5) Epithelial barrier defects; and (6) Others[16]. The pathogenesis along with other extra-intestinal manifestations are discussed in Table 1[14,15,17-74]. This classification helps in understanding the pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and the treatment modalities. Extra-intestinal manifestations of monogenic IBDs can be explained by the involved pathway; certain infections are more commonly associated with specific immunodeficiency syndromes e.g., catalase-positive organisms in CGD and Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) in X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome; autoimmunity is commonly associated with IPEX and IPEX-like conditions and lymphoproliferative disorders are seen in CTLA-4 insufficiency, X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome, IL-10 signaling defects[5]. In the presence of such extraintestinal manifestations, one should look for monogenic IBD. Similarly, if a child is diagnosed with a monogenic defect, one should look for the associated extraintestinal manifestations. As far as the treatment is concerned, some primary immunodeficiencies like WAS and CGD benefit from HSCT, however, epithelial barrier defects do not respond to HSCT due to their inherent defect in barrier function[16]. Targeted therapies are available for specific conditions e.g., IL-1β receptor antagonist in CGD and mevalonate kinase deficiency, CTLA-4 agonist in CTLA-4/ LRBA deficiency, ruxolitinib in Janus kinase 1 (JAK1) gain of function (GOF) mutation[5].

| Group | Genetic condition/ gene (in capital letters)/mode of inheritance (in brackets)1 | Pathogenesis/mechanism | Disease phenotype | Associated manifestations | Ref. |

| Dysfunction of neutrophil granulocytes | 5 components of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate hydrogen oxidase (phox) | ||||

| Gp91-phox, CYBB (X-linked), p22-phox, CYBA (AR), p47-phox, NCF1 (AR), p67-phox, NCF2 (AR), p40-phox, NCF4 (AR) | Decreased neutrophil oxidative burst in the intestinal mucosa predisposes to ineffective clearance of bacteria, which provokes a granulomatous reaction, leading to chronic inflammation characteristic of CD, hypergammaglobulinemia | Crohn’s like colitis/IBD-U, recurrent non-bloody diarrhea | Recurrent infections with catalase positive organisms, gastric outlet obstruction epithelioid granulomas in histopathology, pigmented macrophages and multinucleate giant cells | Marks et al[29], Angelino et al[30], Korzenik et al[31] | |

| Defects in glucose-6-phosphate-translocase, SLC37A4 (AR) | Neutropenia, neutrophil dysfunction | Crohn’s like colitis, perianal fistula | Hypoglycemia, hepatomegaly, bleeding manifestations | Melis et al[74] | |

| Glucose-6-phosphatase-catalytic subunit 3, G6PC3 (AR) | Severe congenital neutropenia, insufficient utilization of glycolysis in neutrophils and monocytes in response to lipopolysaccharides hypoglycolytic neutrophils and monocytes release IL-1β and IL-18 (cause pyroptosis) | Crohn’s like colitis, stricturizing disease | Oral ulcers, arthritis, superficial venous patterns, cardiac defects, facial dysmorphism | Mistry et al[32], Boztug et al[33] | |

| Leukocyte adhesion deficiency 1, ITGB2 (AR) | Leukocytosis, defective chemotaxis and bacterial killing, paucity of tissue neutrophils leads to excessive production of IL-23 and IL-17, which are pro-inflammatory | Crohn’s like colitis, stricturizing phenotype | Recurrent skin infections without pus formation, delayed separation of umbilical cord, periodontal infections | Moutsopoulos et al[34] | |

| Hyper- inflammatory and auto-inflammatory disorders | Mevalonate kinase deficiency, mevalonate kinase, MVK (AR) | Defect in mevalonate pathway of cholesterol synthesis, leading to innate immunity activation, and excessive IL-1β, IL-6, TNF secretion | Neonatal onset UC, perianal disease, strictures | Recurrent fever, arthralgia, hyperimmunoglobulinemia D | Favier et al[25] |

| Autoinflammatory phospholipase Cγ2-associated antibody deficiency and immune dysregulation, phospholipase C gamma 2, PLCG2 (AD) | Activation of phospholipase Cγ2 leads to NLRP3 inflammasome activation | Infantile-onset UC | Arthralgia, conjunctivitis, urticaria, pyoderma gangrenosum, vesciculo-pustular rashes, sinopulmonary infections, low Igs (IgM, IgA, IgG, B cells and NK cells) | Wu et al[35] | |

| Familial MEFV, MEFV (AR) | MEFV encodes pyrin, which regulates caspase-1 activation and suppresses IL-1β activation | Crohn’s like colitis, IBD-U, stricturizing disease, infantile UC | Recurrent fevers, erythematous rash, serositis | Yokoyama et al[26] | |

| Hermansky Pudlak Syndrome, HPS1, adaptor related protein complex 3 subunit beta 1, HPS3, HPS4, HSP5, HPS6, DTNBP1, BLOC1S3, PLDN (AR) | Impaired antimicrobial activity due to abnormal lysosomal trafficking | Crohn’s colitis, fistulizing, perianal disease | Partial albinism, bleeding tendency, recurrent infections, macrophage activation syndrome, ceroid lipofuscin in the reticuloendothelial system | Bolton et al[15], O'Brien et al[36] | |

| X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome 2, XIAP (X-linked) | XIAP is required for NOD1 and NOD2 signaling, and provides innate immunity against pathogens by activation of the of NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinases pathways, provides anti-fungal immunity by Dectin-1 signaling and regulates the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome. XIAP loss causes dysregulation of classical caspase-1/inflammasome activation, overproduction of inflammatory cytokines and cell death | Crohn’s like colitis, perianal disease | Recurrent infections, HLH, splenomegaly, cytopenia, arthritis skin abscesses, EBV and CMV infections, cytopenias, splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, hypogammaglobulinemia | Mudde et al[22] | |

| TRIM22 defect, TRIM22 (AR) | It is expressed in the intestine and macrophages, TRIM22 variants disrupt both NOD2- dependent NF-κB and IFN-β signaling | Crohn’s like colitis, perianal disease | Granulomatous colitis, fever, oral ulcers | Li et al[37] | |

| Familial HLH type 5, STXBP2 (AR) | Defective vesicle transport in NK cell and cytotoxic T cells lead to impairment of degranulation, STXBP2 can disrupt NHE3 trafficking, this changes the gut microbiota resulting in IBD | Intractable diarrhea | HLH, Crohn’s like colitis, perianal disease, microvillous inclusion disease | Fujikawa et al[38] | |

| Complex defects in T cells and B cells function | LRBA deficiency, LRBA (AR) | LRBA is involved in vesicular trafficking of CTLA-4, its absence leads to rapid degradation of CTLA-4, leading to diminished CTLA-4 in Tregs and activated conventional T cells, (CTLA-4 competes with CD28 and terminates excessive T cell proliferation by binding to CD80/86) Increased double-negative T cells, decreased B cells, hypogammaglobulinemia, low ratio of naïve: Memory T cells, and reduced capacity of T cells to secrete various cytokines following stimulation, lower expression of CD 25 and FOXP3 in Tregs | Crohn’s like enterocolitis (IPEX-like) | Erythema nodosum, AIHA, T1DM, hepatitis, uveitis, psoriasis, thyroiditis, splenomegaly, lymphoproliferation, Burkitt’s lymphoma, exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, interstitial lung disease, repeated sino-pulmonary infections (presents early in pre-school children) | Vardi et al[19], Lo et al[39] |

| CTLA-4 insufficiency, CTLA-4 (AD) | CTLA-4 is constitutively active in Tregs and expressed in conventional T cells upon activation. It inhibits immune responses, by competing with the costimulatory molecule CD28 for the ligands CD80 and CD86 on the antigen-presenting cells. Its insufficiency leads to excess T cell activation, lymphoproliferation, autoimmunity and compromised B cell function (due to chronic B cell stimulation) | CD, UC, IPEX-like | T1DM, autoimmune thyroiditis, interstitial lung disease, AIHA, immune thrombocytopenia, lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, gastric adenocarcinoma, demyelinating encephalopathy (presents in young adults) | Schwab et al[18], Lo et al[40] | |

| Common variable immunodeficiency type 1, ICOS deficiency, ICOS (AR) | ICOS expression is upregulated upon T cell activation and it delivers a positive co-stimulatory signal to T cells. It is required for T-B cell coactivation, CD40-mediated Ig class switch and Th2, Th17 immune responses. It is also crucial for the development of Tregs | Crohn’s like entero-colitis | Recurrent bacterial and viral (herpes, CMV) infections, lymphoproliferative diseases splenomegaly, autoimmune cytopenia, autoimmune interstitial pneumonitis, psoriasis | Abolhassani et al[41], Schepp et al[42] | |

| IL-21 deficiency, IL-21 (AR) | IL-21 receptor mediates CD8+ T cell activation and proliferation, NK cell maturation, and differentiation of CD4+ T cells, including Tregs, most potent action on B cells; isotype switching, hypogammaglobulinemia | Crohn’s like entero- colitis | Recurrent sino-pulmonary and gastrointestinal bacterial and fungal infections, cryptosporidiosis-related cholangitis, neutropenia, asthma, urticaria | Cagdas et al[43] | |

| Hyper-Ig, IgM syndrome, CD40L (X-linked), activation-induced cytidine deaminase, AICDA (AR) | Defective isotype switching, elevated/normal IgM; low IgA and IgG, CD40 is expressed on antigen presenting cells, B cells and macrophages; and CD40 Ligand is expressed on T cell. Peripheral B cell tolerance development requires CD40-CD40 L and major histocompatibility complex-II T cells receptor interaction, its absence leads to autoimmunity. Additionally, there are decreased Tregs in hyper IgM syndrome | Crohn’s like colitis | Sinopulmonary infections, susceptibility to intracellular organisms, Pneumocystis pneumonia, cryptosporidium infections, sclerosing cholangitis, neutropenia, AIHA, aphthous stomatitis | Jesus et al[44], Hervé et al[45] | |

| Agammaglobulinemia, BTK (X-linked) | Absent B cells, hypogammaglobulinemia. BTK inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activity. Disinhibited NLRP3-meditates proinflammatory IL-1β and IL-18 signaling leading to CD like colitis | Crohn’s like colitis, stricturizing, fistulizing disease | Recurrent gastrointestinal infections, sino-pulmonary infections, AIHA | Khan et al[46], Mao et al[47] | |

| WAS, WASP (X-linked) | WAS protein is involved in T cell dependent activation, cytotoxic function of CD8+ T cells, Tregs and NK cells. Motility and migration of B cells is defective microbial dysbiosis, ineffective suppression of effector T cells and B cells by Tregs leads to autoimmunity | UC-like colitis, CD, IBD-U | Microthrombocytopenia, eczema, atopic dermatitis, skin vasculitis, AIHA, neutropenia, lymphoreticular malignancy, B cells lymphoma | Suri et al[28], Catucci et al[48] | |

| ARPC1B deficiency, ARPC1B (AR) | Arp2/3 complex is involved in actin polymerization and cell migration of neutrophils, T cells and platelets | UC | Recurrent infections, microthrombocytopenia, eosinophilia, elevated IgE, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, bleeding manifestations, food allergies (resembles WAS) | Kahr et al[49] | |

| Omenn syndrome, DOCK8 (AD/AR) | DOCK8 has a role in regulating actin cytoskeleton, thereby implicated in causing immunodeficiency, atopy, autoimmunity and malignancies | Crohn’s like colitis | Atopy, staphylococcal infection, cutaneous viral infections, candidiasis, food allergy, autoimmunity, vasculitis, autoimmune hepatitis, hyper IgE, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation curative | Engelhardt et al[50], Sanal et al[51] | |

| Phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase activation syndrome 1 and 2, phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit delta, PIK3CD (AD), phosphoinositide-3-kinase regulatory subunit 1, PIK3R1 (AR) | Hyperactivation of the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway leads to senescent T cells, impaired B cell maturation, elevated/normal IgM, absent class switched memory B cells | Colitis | Recurrent sino-pulmonary infections, cytopenia, hepatosplenomegaly, lymphoproliferation, increased risk of lymphoma, viral infections | Tessarin et al[52] | |

| X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency disease, IL-2RG (X-linked) | Mutation in the gene encoding IL-2 receptor | Colitis | Most common sub-type, recurrent fungal/viral opportunistic infections, lymphopenia, Reduced circulating T cells and NK cells | Ouahed et al[24], Justiz-Vaillant et al[53], Felgentreff et al[54] | |

| ADA deficiency, ADA (AR) | Deficiency of ADA leads to accumulation of deoxyadenosine, which is toxic to lymphoid precursors | Colitis | Recurrent infections, hearing and visual impairment, skeletal abnormalities | Justiz-Vaillant et al[53], Felgentreff et al[54] | |

| RAG-1 and RAG-2 mutations (AR) | Defect in T cells receptor development leading to abnormal T cells | Colitis | Recurrent infections, reduced T and B cells | Justiz-Vaillant et al[53], Felgentreff et al[54] | |

| DNA Ligase IV deficiency, Ligase IV, LIG4 (AR) | DNA ligase IV is involved in DNA double-strand breaks repair and class switching | Enterocolitis, colitis | Recurrent infections, growth retardation, facial dysmorphism, myelodysplastic syndrome, Reduced T and B cells, vitiligo, pancytopenia, thrombocytopenia | Sun et al[55] | |

| CD3G mutations (AR) | Arrest of T cell differentiation, impaired T cell activation, loss of Treg functions lead to autoimmunity | Colitis, autoimmune enteropathy | Recurrent bacterial/ viral infections, AIHA, chronic interstitial lung disease | Rowe et al[56] | |

| ZAP70-related combined immunodeficiency, ZAP-70 (AR) | Abnormal T cell differentiation, peripheral CD4+ T cells are refractory to T cells receptor-mediated activation | Colitis | Recurrent viral and fungal infections, reduced CD4+ T cells, and CD8+ T cells, autoimmune cytopenia | Shirkani et al[57] | |

| Artemis-deficiency combined immunodeficiency DCLRE1C (AR) | DCLRE1C codes for artemis, which is a component of V(D)J recombination and the non-homologous end-joining pathway, for degeneration of antigen diversity and early T and B cell maturation | Crohn’s like colitis | Recurrent sinopulmonary infections, fungal and viral infections, bacillus calmette-guerin adenitis, reduced T cells and B cells, normal NK cells | Ghadimi et al[58] | |

| Defects in TGF-β signaling TGF-β1 deficiency, TGF-β1(AR) | TGF-β regulates the survival and differentiation of various immunological (T cells, B cells, NK cells and dendritic cells) and non-immunological cells | Infantile-onset IBD, perianal disease | Recurrent infections, skeletal muscle atrophy, neurological symptoms epilepsy, leukoencephlopathy | Kotlarz et al[59] | |

| Loeys-Dietz syndrome TGF-βR1/TGF-βR2 (AR) | UC | Cranio-facial dysmorphism, hypertelorism, cleft palate, bifid uvula, hyperextensible joints, cardiovascular anomalies like dilatation of aortic root | Naviglio et al[60] | ||

| RIPK1 deficiency, RIPK1 (AR) | RIPK1 is a central regulator of apoptosis and inflammation. Inflammasome is activated in RIPK1 deficient macrophages leading to secretion of inflammatory cytokines | Infantile-onset IBD, perianal disease | Severe bacterial, viral infections, arthritis, recurrent fever | Sultan et al[61] | |

| Tregs and IL-10 signaling | IL-10 signaling defect, IL-10 RA and IL-10RB (AR), IL-10 (AR) | IL-10 is released by type 2 helper T cells, it inhibits Th1 pathway and limits the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-2 IFN-γ, TNF-α and IL-12 | Severe early onset enterocolitis, Perianal disease, fistulizing disease | Folliculitis, pneumonia, arthritis | Glocker et al[62] |

| Immune dysregulation polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X linked (IPEX), FOXP3 (X-linked) | FOXP3 is a regulator of Treg development and competitiveness. Treg downregulate activated B cells | Early onset small bowel type, intractable diarrhea in infancy, graft-versus-host disease like changes (apoptotic bodies) | Classic triad: Intractable diarrhea, T1DM and eczema. Atopic eczema, hypoparathyroidism, hashimoto thyroiditis, AIHA, antibody-mediated cytopenia, lymphadenopathy, CMV/EBV infection, food allergies | Gambineri et al[17], Consonni et al[63] | |

| IPEX-like syndromes: Defects in the IL-2 receptor α chain, IL-2RA/CD25 (AR) | Normal FOXP3 expression with CD25 deficiency. CD25 deficiency leads to Treg dysfunction | Autoimmune enteropathy, villous atrophy | Multisystem autoimmunity, lymphoproliferation, polyendocrinopathy, eczema, hemolytic anemia | Gambineri et al[17], Caudy et al[64] | |

| STAT1 GOF disease (AD) | STAT1 is a cytoplasmic transcription factor which binds to JAK in response to IFNs and IL-27. In STAT1 GOF mutation, there is enhanced STAT1-dependent response to type I and II IFNs | Severe autoimmune enteropathy, CD, UC | Recurrent viral infections, EBV, CMV, candidiasis, hypothyroidism, early onset diabetes, recurrent sinopulmonary infections, hypogammaglobulinemia | Okada et al[20] | |

| STAT3 GOF disease (AD) | STAT3 GOF leads to prolonged activation of STAT3 and its downstream effects, which include lymphoproliferation, autoimmunity | Severe autoimmune enteropathy | Diffuse lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly, cytopenias, interstitial lung disease, early onset type 1 diabetes, vasculitis, arthritis, recurrent viral, fungal and bacterial infections | Vogel et al[21] | |

| JAK1 GOF disease (AD) | JAK1 GOF leads to downstream activation of JAK/STAT pathway and associated inflammatory disease | IBD-U | Pruritus, atopic dermatitis, ichthyosis, arthralgia, calcifying fibrous tumors | Fayand et al[23] | |

| Epithelial barriers | TTC7A deficiency, TTC7A (AR) | TTC7A dysfunction leads to loss of polarity of intestinal epithelium and poor barrier function | Severe enterocolitis from birth | Multiple intestinal atresia from pylorus, small bowel, ileocaecal valve to colon, combined immunodeficiency, lymphocytopenia | Jardine et al[65] |

| NEMO deficiency, inhibitor of NF-κB kinase regulatory subunit gamma, IKBKG (X-linked) | NEMO deficiency leads to impairment in toll-like receptor signaling, B cell response, impaired T cell response | Crohn’s colitis | Anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia involving skin, teeth, viral and fungal infections | Miot et al[27] | |

| ADAM-17 deficiency, ADAM-17 (AR) | ADAM-17 sheds cytokine and cytokine receptors including TNF-α and TNF receptors, and IL-6 receptors | Neonatal IBD | Alopecia, erythroderma, recurrent sepsis, eosinophilia, lymphadenopathy | Imoto et al[66] | |

| Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa, COL7A (AR) | Defective barrier function triggers inflammation | UC | Blistering skin condition, photosensitivity, esophageal strictures | Zimmer et al[67] | |

| Kindler syndrome, fermitin family member 1, FERMT1 (AR) | Altered kindlin-1 leads to epithelial barrier disruption in colonic epithelium, leads to penetration of antigens and IBD | UC, CD | Neonatal onset inflammatory skin disease, poikiloderma, strictures, esophagitis | Roda et al[68] | |

| Familial diarrhea, guanylyl cyclase 2C, GUCY2 (AD) | GOF mutation in the guanylate cyclase-coupled receptors leads to signaling to cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator and increases chloride secretion | Secretory diarrhea | Secretory diarrhea, failure to thrive, antenatal polyhydramnios | Fiskerstrand et al[69] | |

| Congenital sodium diarrhea, solute carrier family 9 isoform 3, SLC9A3 (AR) | Defective the Na+/H+ exchanger NHE3 leads to impaired sodium absorption and alters microbiome | Congenital sodium diarrhea (early and adolescent onset UC) | Secretory diarrhea, failure to thrive, antenatal polyhydramnios | Janecke et al[70] | |

| Trichohepatoenteric syndrome, TTC37 or SKIV2 L (AR) | Abnormalities of the expression and localization of transporter proteins in the enterocytes and hepatocytes | Diarrhea (both secretory and osmotic) | Facial dysmorphism, trichorrhexis nodosa, low Igs, congenital cardiac anomalies, enlarged platelets, liver disease, rarely liver failure, intra uterine growth retardation | Hartley et al[71] | |

| Others | Endothelial cell defects | Azabdaftari et al[14] | |||

| Chronic enteropathy associated with SLCO2A1 gene, SLCO2A1 (AR) | SLCO2A1 encodes prostaglandin transporter, which mediates PGE2 uptake and inactivation in gastrointestinal tract. Its absence leads to elevated serum PGE2, has pro-inflammatory effects and disrupts mechanical barrier | Multiple strictures of the small intestines | Protein-losing enteropathy, iron deficiency anemia, intestinal obstruction, primary hypertrophic osteoarthropathy | Xie et al[72] | |

| CHAPLE, CHAPLE syndrome (AR) | CD55 is expressed in capillary endothelium, brush-border and lymphocytes, and is a complement regulatory protein. Its absence leads to decreased IL-10 secretion, excessive complement activation, TNF secretion and intestinal inflammation | Protein-losing enteropathy | Hypogammaglobulinemia, recurrent respiratory infections, deep vein thromboses, polyarthritis | Ozen et al[73] |

Early onset of disease, especially within the first two years of life, is a strong indicator of monogenic IBD; in a cohort of 62 patients of infantile-onset IBD, there were 19 cases (30.6%) of monogenic IBD and in a large cohort of 207 patients of VEO-IBD, monogenic IBD was diagnosed in 32% (66/207)[75,76]. So far, there are no studies showing the proportion of monogenic IBD in adult-onset IBD. Between the ages of 6 and 18 years, Charbit-Henrion et al[76] found 18.2% (4 of 22), Uchida et al[2] reported 25.9% (7/27) cases of monogenic IBD. Crowley et al[12] have shown that the proportion of monogenic IBD was 2.3% among children aged 6-18 years. Coming to the disease phenotype, IBD is categorized into 3 categories; Crohn’s disease (CD), ulcerative colitis (UC) and IBD-unclassified (IBD-U) based on the Porto criteria. The younger the presentation, the more likely phenotype is UC/IBD-U. In one of the largest cohort of pediatric IBD of 1005 children, of the 31 monogenic IBD cases, almost 55% had CD, however, among the VEO-IBD patients, UC/ IBD-U was the commonest (81.8%, 9/11)[12]. Similarly, in a cohort of infantile-onset IBD, the most common phenotype was IBD-U (73.6%, 14/19)[75]. Based on the extent of disease, in a systematic review of cases of 207 cases of VEO-IBD with severe disease course, the common presentations were colitis alone in 59.4%, small bowel inflammation in 24.6%, and colitis with perianal disease in 16%; among these, the highest proportion of molecular diagnosis was seen in the small bowel inflammation phenotype (61%) followed by colitis with perianal disease (39%)[76]. Perianal disease was seen strongly associated with IL-10 signaling pathway defects, transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGFB1), XIAP mutations[10,76]. A three-generation pedigree analysis and focused physical examination often provides vital clinical clues towards the underlying disorder. In a systematic review of 750 cases of monogenic IBD, 23.1% had a family history of IBD and 21.7% had consanguinity and the most commonly reported monogenic IBD was 10RA mutation[5]. Patients with IL-10, IL-10RA/B mutations, WAS, TTC7A, epithelial cell adhesion molecule, forkhead box protein 3 (FOXP3) mutations etc. usually have their onset of symptoms very early in life[77,78]. However, there are certain mutations like neutrophil disorders, guanylyl cyclase 2C mutation, IPEX syndrome, which have uncommon variants with variable age of presentation[17,78,79].

Coming to the extra-intestinal manifestations, the most common manifestation is recurrent or severe or atypical infection, as a vast majority of monogenic IBD are primary immunodeficiencies[5]. Other manifestations include skin changes, autoimmunity, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, food allergies, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), facial dysmorphism (Tables 1 and 2)[14,15,17-74]. Dermatological manifestations like epidermolysis bullosa, blistering skin conditions, eczema, alopecia, ectodermal dysplasia, trichorrhexis nodosa are commonly associated with epithelial defects[78]. Severe perianal disease, folliculitis, and/or arthritis in early infancy suggest IL-10 signaling defects[77]. Autoimmune conditions like autoimmune anemia, autoimmune thrombocytopenia, type 1 diabetes mellitus, autoimmune thyroiditis, interstitial pneumonia, or other multi-organ autoimmune disorders, are seen in IPEX syndrome (FOXP3) or in CTLA-4 insufficiency, LRBA deficiency, IPEX-like syndromes like signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) gain-of-function (GOF), STAT3 GOF mutations[17-21]. Lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, HLH is seen in lymphoproliferative disorders e.g., X-linked lymphoproliferative disease (XLP), CTLA-4/LRBA deficiency, IPEX syndrome, STAT1 GOF, STAT3 GOF mutations[17,18,20-22]. Patients with glycogen storage disease (GSD)-1b can have IBD-like presentation[74]. In these patients, hypoglycemic symptoms and large, soft hepatomegaly point towards GSD. HLH induced by EBV or cytomegalovirus may be caused by XIAP, mevalonate kinase, and syntaxin-binding protein-2 mutations[5,78]. History of delayed cord detachment and abscess without pus often points towards leukocyte adhesion defect (LAD). Other extra-intestinal manifestations are shown in Table 2.

| Clinical clues | Underlying condition/affected genes |

| Epidermolysis bullosa, nail dystrophy | Epithelial barrier defect (IKBKG, a disintegrin and metalloproteinase 17, COL7A1) |

| Woolly hair, trichorrhexis nodosa | Tricho-entero-hepatic syndrome |

| Severe perianal disease (rectovaginal fistula), folliculitis, and/or arthritis | IL-10 signaling pathway defects |

| Abscess without pus | Leukocyte adhesion defect |

| Eczema | Wisckot-Aldrich syndrome, hyper immunoglobulin E syndrome, IPEX syndrome, IKBKG defect |

| Hepatosplenomegaly | Chronic granulomatous disease |

| Autoimmune anemia, type 1 diabetes mellitus, autoimmune thrombocytopenia, autoimmune thyroiditis, interstitial pneumonia | IPEX, IPEX-like syndromes |

| No bacillus calmette-guerin scar | T cell defect |

| Oral ulcer, leukoplakia | Dyskeratosis congenita 1, regulator of telomere elongation 1 |

| Dysmorphic features | IKBKG, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma translocation protein 1, glucose-6-phosphatase-catalytic subunit 3, SKIV2 L |

| Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, macrophage activation syndrome | X-linked inhibitors of apoptosis, mevalonate kinase, syntaxin-binding protein-2 |

| Periostosis | Solute carrier organic anion transporter family member 2A1 |

| Albinism | Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome 1/4/6 |

| Malignancy (lymphoma, gastric adenocarcinoma) | IL-10/IL-10RA/B, lipopolysaccharide-responsive and beige-like anchor protein, cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 |

| Absent tonsils | Agammaglobulinemia |

We should keep in mind that not all VEO-IBD are monogenic IBD. Monogenic IBD is a distinct subset that requires a separate diagnostic and therapeutic approach. Presentation at early ages, especially less than 2 years, presence of consanguinity and sibling death, presence of perianal disease as well as extraintestinal co-morbidities (such as autoimmunity, tumors etc.) and failure to respond to conventional immunosuppression points towards monogenic IBD. The mnemonic “Young age matters most” best describes the appropriate clinical scenarios to suspect monogenic IBD (Table 3)[16].

| Conditions to suspect monogenic IBD |

| Young age matters most |

| Young age (onset < 2 years/< 6 years with red flags) |

| Multiple family members with IBD with suspected monogenic disorder and consanguinity |

| Autoimmunity |

| Thriving failure |

| Treatment with conventional medication fails |

| Endocrine concerns |

| Recurrent infections or unexplained fever |

| Severe perianal disease |

| Macrophage activation syndrome and hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis |

| Obstruction and atresia of the intestine |

| Skin lesions, dental and hair abnormalities |

| Tumors |

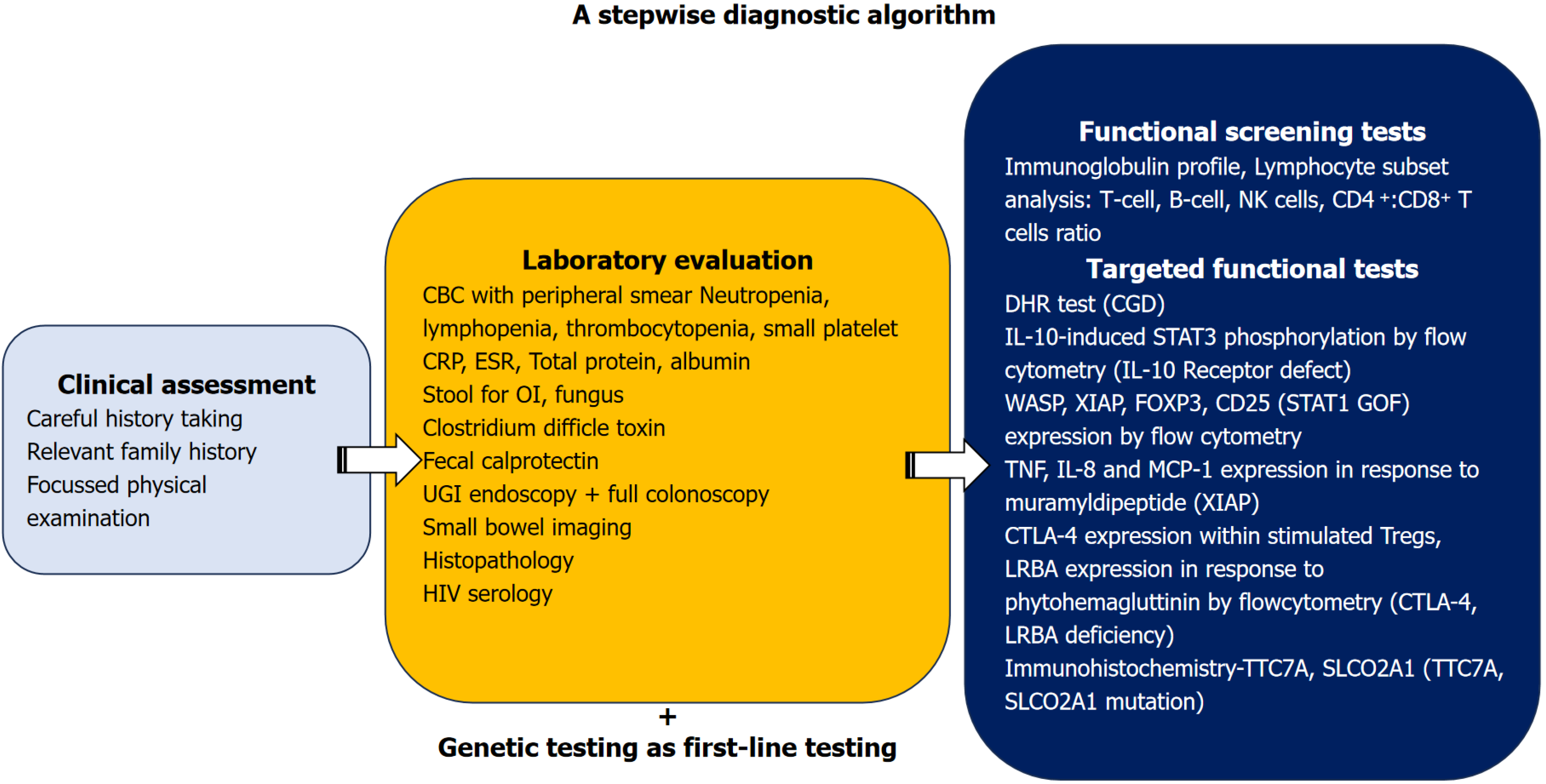

The evaluation of monogenic IBD requires a systematic approach. A diagnostic algorithm has been depicted in Figure 1. When a child presents with colitis at a young age, the child should be evaluated for common causes such as infectious and allergic causes e.g. cow milk protein allergy in infants. When the child doesn’t respond to antibiotics or change in the diet even after good compliance, IBD should be considered. Evaluation of IBD calls for complete blood count, inflammatory markers like C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, total protein and albumin for gastrointestinal protein losses. Complete blood count with peripheral smear can provide many diagnostic clues such as neutropenia e.g., cyclic neutropenia in GSD-1b, very high total leukocyte count in LAD, small-sized platelets and thrombocytopenia in WAS. Full colonoscopy with ileoscopy and upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (with all segment biopsies) with or without enterography should be done for classification of IBD as per Porto criteria, which also helps in guiding the diagnosis. If monogenic disease is suspected, functional screening tests like Ig profile, lymphocyte sub-set assay (CD4, CD8, CD19/CD20, natural killer cells) should be done. High levels of IgE and/or eosinophilia are also found in patients with monogenic disorders caused by defects in FOXP3, IL-2RA, IKBKG, WAS, or dedicator of cytokinesis 8 (DOCK8) as well as Hyper-IgE syndrome[78]. Assessment of oxidative burst by neutrophils (using the nitroblue tetrazolium test or flow cytometry-based assays such as the dihydrorhodamine fluorescence assay) has been a useful in the diagnosis of CGD with good sensitivity[80,81].

With the advent of NGS, the diagnostic approach to monogenic IBD has seen a paradigm change from deep phenotyping followed by sequential genetic testing towards parallel genetic testing as the first line diagnostic tool. NGS by WES offers the advantage to simultaneously look at multiple genes and is less time-consuming and less expensive compared with sequential sequencing in patients presenting with nonspecific clinical phenotype. Studies[2-4,75,76,78] on genetic diagnosis of monogenic IBD have used different methods of genomic analysis, most have used a combination of targeted genetic panel while in a recent study, Crowley et al[12] have used trio WES. The older studies had used targeted gene panels, however as the cost of WES and whole genome sequencing (WGS) is coming down, more centers are using WES/WGS. The disadvantage with the targeted gene panel is that various newer genetic mutations may be missed if they are not covered by the panel. These varied genetic panels might have led to varying diagnostic yields. Also, the study population varied; as some performed WES in all pediatric IBD[12] while others targeted a population of infantile-onset IBD or VEO-IBD[2-4,75,76]. Sanger sequencing or functional tests were used in most of the studies to verify the pathogenic variation. To summarize, targeted panels can be used if a specific disease is suspected, while WES should be considered when the disease phenotype doesn’t fit into a single disorder or if there are newer manifestations. Strategies which can improve the diagnostic yields are (1) Updating the targeted gene panels as per emerging evidence; (2) Performing WES in cases where IBD is strongly suspected but is undetected on the targeted gene panels; and (3) Re-analysis of undiagnosed strongly suspected cases with emerging genomic data[82]. Certain important points to consider before considering genetic study are (1) The gene panels should include all causative diseases; (2) A WES may miss copy number variants (CNVs), which are picked up on targeted panel NGS; (3) Deep intronic defects might be missed by WES; and (4) If the clinical phenotype doesn’t fit with the described genetic defect, one must consider that this might be caused by unknown modifier genes, in such a scenario, specialized validation tests can be done[76,78]. Functional tests give early results (e.g., WAS protein, XIAP, FOXP3 expression by flow cytometry) although not all these tests are available in a resource-limited setting. Other than this, functional tests should be done to validate a novel mutation or in situations where the clinical phenotype is not explained by the genetic diagnosis, or in case the genetic analysis fails to detect any pathogenic variants, or in the presence of a variant of unknown significance[10]. However, these tests are available for a small number of monogenic IBD. Some common functional tests are shown in the Figure 1. The consensus guidelines by the British Society of Gastroenterology and British Society of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition suggest genomic testing (with a curated adaptable gene panel approach covering 102 causative genes) for all patients with infantile-onset IBD and in patients of VEO-IBD who fulfil one or more additional testing criteria and in those aged > 6 years, when at least one testing criteria is met, which is similar to an earlier guideline by the Pediatric IBD Porto group of ESPGHAN (ESPGHAN guidelines are older and had covered 75 genes)[10,82]. Genomic testing criteria include early age of onset < 6 years, susceptibility to infections with abnormal laboratory tests, features of autoimmunity, congenital multiple intestinal atresias, early-onset malignancy at an age < 25 years, family history of suspected monogenic IBD and those patients who are planned for HSCT or have undergone multiple resections requiring parenteral nutrition and other supportive features like family history, growth failure, severe perianal disease or refractory IBD[82]. Both these guidelines suggest that a genetic panel of known mutations (which needs to be updated with the evolution of newer mutations) or WES, or whole genomic sequencing have complementary diagnostic roles[10,82]. A genomic IBD multidisciplinary team of a gastroenterologist, geneticist, immunologist, dietician, IBD nurse and bone marrow transplant physician is required for expedited genetic diagnosis and appropriate treatment decisions.

The majority of monogenic IBD patients do not respond to conventional immunosuppression with steroids and immunomodulators[5,6,11,78]. Biologicals are the primary treatment modality. However, clinicians need to be careful as it may worsen infection in certain genetic conditions leading to poorer outcome e.g., anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) drugs in CGD may cause life-threatening infections[83]. In a systemic review of 750 cases of monogenic IBD, biologic therapy was required in 32.9% (247 cases), and was effective only in 25.5% of them[5]. Other than anti-TNF agents, various targeted therapies have proved to be beneficial in disorders of immune dysregulation and autoinflammatory diseases. Autoimmune features in IPEX syndrome respond to corticosteroids along with other immunosuppressants like calcineurin inhibitors (either cyclosporine A or tacrolimus), rapamycin, azathioprine[17]. Ruxolitinib, tofacitinib, baricitinib (JAK inhibitors) are useful in autoimmunity associated with IPEX-like syndromes (STAT1 GOF, STAT3 GOF, and JAK1 GOF)[20,21,23]. Abatacept can be used as a bridge to HSCT in CTLA-4 insufficiency/LRBA deficiency, colchicine and anti-IL-1β agents (canakinumab) are effective in Familial Mediterranean fever and anakinra and canakinumab (anti-IL-1 agents), tocilizumab (anti-IL-6) in mevalonate kinase deficiency[24-26,84,85].

HSCT has emerged as a potentially curative therapy in primary immunodeficiencies and disorders of immune dysregulation, while it is of no benefit in patients with epithelial barrier defects. For patients with IL-10/IL-10R pathway defects, IPEX syndrome, severe combined immunodeficiency disease (SCID), CGD, WAS, and X-linked lymhoproliferative syndrome (XIAP mutation), HSCT is the treatment of choice and usually has good outcome[5,6,9,86,87]. However, it can be detrimental in patients with epithelial barrier defects like nuclear factor-kappa B essential modulator (NEMO), TTC7A mutations[5,24,27,88]. Hence, the importance of genetic diagnosis before deciding the appropriate treatment modality cannot be over-emphasized.

As IL-10 is expressed predominantly on hematopoietic and immune cells, allogeneic HSCT has been used as a curative therapy for patients with IL-10 or IL-10R mutations with favorable outcomes while results of conventional immunosuppression therapy as well as anti-TNF-α agents have been disappointing[6,13,77]. Engelhardt et al[89], in a series of 9 children with IL-10/IL-10R mutations, have shown that all the three children receiving HSCT were cured while the rest 6 children receiving other immunosuppressive therapy did not show any response.

The treatment of IPEX syndrome has shown a gradual shift from conventional immunosuppressive therapy to HSCT over the last few decades[17,90]. In a large, multicentric retrospective study, Barzaghi et al[90], studied the long-term outcome of 96 patients with IPEX syndrome after HSCT (n = 58) and immunosuppressive therapy (n = 38) over a median follow-up of 2.7 years (range 1 week-15 years) and 4 years (range 2 months-25 years) respectively; the overall 5-year survival after HSCT was 73.2% (95%CI: 59.4-83.0) and 65.1% (95%CI: 62.8-95.8) after immunosuppression. Patients on immunosuppressive therapy had frequent relapses while none had relapses after HSCT[90]. Similar encouraging results with HSCT have been reported in patients with CGD and WAS. Multiple studies have demonstrated 3-year overall survival rates of more than 80% in patients with both CGD and WAS after HSCT[28,86,87,91]. Anti-IL-1 receptor antagonist has shown benefit in CGD while anti-TNF agents increase the risk of infections and death[16,83].

Management of XLP2 (XIAP) depends of the disease manifestation; HLH is treated according to the HLH protocol, hypogammaglobulinemia may require Ig replacement, however IBD doesn’t respond to conventional treatment but requires surgery and the only curative treatment option is HSCT[22]. Outcomes of HSCT in XLP2 have been variable; a recent Japanese study of 10 patients showed a successful outcome, with a post-HSCT survival of 90% at a median follow-up of 21.2 months[92,93]. In CTLA-4 insufficiency with IBD, corticosteroids, anti-TNF agents, vedolizumab and sirolimus have shown variable response. Abatacept (the CTLA-4 fusion protein, CTLA-4–Ig, which substitutes CTLA-4) is recommended as first-line steroid sparing agent in these patients[84]. In refractory IBD, HSCT has shown good response; in a series of 40 patients who underwent HSCT for CTLA-4 insufficiency, 17 patients had enteropathy before HSCT, 16 showed reduction in the disease severity, post-HSCT[94]. Patients require treatment for other manifestations of CTLA-4 insufficiency, e.g., symptomatic lymphoid infiltration of organs/autoimmune cytopenias require treatment with corticosteroids with or without rituximab, Ig replacement is used in those with hypogammaglobulinemia[84]. Similarly in LRBA deficiency, abatacept has been used for autoimmune manifestations, including enteropathy either alone or in combination with sirolimus with good response in comparison to conventional immunosuppression; among 61 patients who received immunosuppression as primary therapy, 72.1% showed either partial or no disease control and required additional immunosuppressants, abatacept or HSCT[85]. In the same study, HSCT was used as a curative option for refractory disease; among 14 patients who underwent HSCT, 9 showed complete response while 3 continued to require im

There is emerging evidence from mouse models and real-world human studies that patients with epithelial barrier defects are less amenable to HSCT, since this does not correct the defect that causes the disease (e.g. NEMO deficiency or TTC7A deficiency)[5,27,88,96]. Patients with TTC7A deficiency might have recurrence of intestinal atresia after HSCT[88,96].

It is imperative to determine the molecular diagnosis for each patient with suspected monogenic IBD before selecting HSCT as a treatment approach as there is significant risk associated with HSCT, including GVHD and severe infections.

Given that genetic testing is generally less aggressively pursued for adult-onset and older pediatric cases than for those under six years of age, clinicians should suspect monogenic IBD more than previously thought, especially if a patient has extraintestinal comorbidities or shows poor response to conventional immunosuppression, even if the patient is not under six years of age.

NGS should be done in parallel to other etiological workup instead of a sequential diagnostic tool after unyielding initial testing. As we embark on the journey of NGS in our clinical practice, we must be aware of its limitations like WES can miss CNVs, intronic variants, synonymous variants, and inversions, etc. Additionally, we should carefully analyze whether the detected mutation is disease-causing or not. Functional tests are an easy way to get an early diagnosis, should be more widely available.

Published literature on many monogenic IBD genes is only in the form of case reports and case series and therefore generalizations about the clinical presentation and course of such conditions should be avoided. The need of the hour is a collaboration between the leading centers of excellence for the treatment of monogenic IBD all over the world, and formation of a genomic IBD multidisciplinary team at each such center of excellence as proposed by Kammermeier et al[82]. This will not only expedite the work-up of exceptional cases of suspected monogenic IBD but also provide insight and promote research in the treatment of newly identified entities. Further studies using techniques like transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics will help in better characterization of individual genetic mutations. Efforts should be made to make functional validation tests more available and affordable.

Timely genetic counselling should be offered to all affected families. An in-depth understanding of the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms of monogenic is of vital importance as it may help in identifying newer molecular pathways and pave the way for newer therapeutic targets.

Overall monogenic IBD is rare, however it is seen in roughly a quarter of children aged less than 6 years of age. One must suspect monogenic IBD in the presence of clinical cues like consanguinity, early age of disease-onset, perianal disease, presence of extraintestinal manifestations like atypical infections, autoimmunity, lymphoproliferative syndromes, malignancies and failure to respond to conventional treatment. Management depends on the immunological pathway involved; many of them being primary immunodeficiency syndromes, benefit from HSCT. An early molecular diagnosis is warranted if the clinical suspicion is high, as it helps in deciding further treatment plans, prognostication and antenatal counselling.

| 1. | Dagci AOB, Cushing KC. Genetic Defects in Early-Onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2023;49:861-874. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Uchida T, Suzuki T, Kikuchi A, Kakuta F, Ishige T, Nakayama Y, Kanegane H, Etani Y, Mizuochi T, Fujiwara SI, Nambu R, Suyama K, Tanaka M, Yoden A, Abukawa D, Sasahara Y, Kure S. Comprehensive Targeted Sequencing Identifies Monogenic Disorders in Patients With Early-onset Refractory Diarrhea. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2020;71:333-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Fang YH, Luo YY, Yu JD, Lou JG, Chen J. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of inflammatory bowel disease in children under six years of age in China. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:1035-1045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lega S, Pin A, Arrigo S, Cifaldi C, Girardelli M, Bianco AM, Malamisura M, Angelino G, Faraci S, Rea F, Romeo EF, Aloi M, Romano C, Barabino A, Martelossi S, Tommasini A, Di Matteo G, Cancrini C, De Angelis P, Finocchi A, Bramuzzo M. Diagnostic Approach to Monogenic Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Clinical Practice: A Ten-Year Multicentric Experience. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26:720-727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nambu R, Warner N, Mulder DJ, Kotlarz D, McGovern DPB, Cho J, Klein C, Snapper SB, Griffiths AM, Iwama I, Muise AM. A Systematic Review of Monogenic Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:e653-e663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 23.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kotlarz D, Beier R, Murugan D, Diestelhorst J, Jensen O, Boztug K, Pfeifer D, Kreipe H, Pfister ED, Baumann U, Puchalka J, Bohne J, Egritas O, Dalgic B, Kolho KL, Sauerbrey A, Buderus S, Güngör T, Enninger A, Koda YK, Guariso G, Weiss B, Corbacioglu S, Socha P, Uslu N, Metin A, Wahbeh GT, Husain K, Ramadan D, Al-Herz W, Grimbacher B, Sauer M, Sykora KW, Koletzko S, Klein C. Loss of interleukin-10 signaling and infantile inflammatory bowel disease: implications for diagnosis and therapy. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:347-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 385] [Cited by in RCA: 344] [Article Influence: 26.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Marsh RA, Rao K, Satwani P, Lehmberg K, Müller I, Li D, Kim MO, Fischer A, Latour S, Sedlacek P, Barlogis V, Hamamoto K, Kanegane H, Milanovich S, Margolis DA, Dimmock D, Casper J, Douglas DN, Amrolia PJ, Veys P, Kumar AR, Jordan MB, Bleesing JJ, Filipovich AH. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for XIAP deficiency: an international survey reveals poor outcomes. Blood. 2013;121:877-883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Speckmann C, Ehl S. XIAP deficiency is a mendelian cause of late-onset IBD. Gut. 2014;63:1031-1032. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Barzaghi F, Passerini L, Bacchetta R. Immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, x-linked syndrome: a paradigm of immunodeficiency with autoimmunity. Front Immunol. 2012;3:211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 238] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Uhlig HH, Charbit-Henrion F, Kotlarz D, Shouval DS, Schwerd T, Strisciuglio C, de Ridder L, van Limbergen J, Macchi M, Snapper SB, Ruemmele FM, Wilson DC, Travis SPL, Griffiths AM, Turner D, Klein C, Muise AM, Russell RK; Paediatric IBD Porto group of ESPGHAN. Clinical Genomics for the Diagnosis of Monogenic Forms of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Position Paper From the Paediatric IBD Porto Group of European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2021;72:456-473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 23.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Heyman MB, Kirschner BS, Gold BD, Ferry G, Baldassano R, Cohen SA, Winter HS, Fain P, King C, Smith T, El-Serag HB. Children with early-onset inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): analysis of a pediatric IBD consortium registry. J Pediatr. 2005;146:35-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 394] [Cited by in RCA: 368] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Crowley E, Warner N, Pan J, Khalouei S, Elkadri A, Fiedler K, Foong J, Turinsky AL, Bronte-Tinkew D, Zhang S, Hu J, Tian D, Li D, Horowitz J, Siddiqui I, Upton J, Roifman CM, Church PC, Wall DA, Ramani AK, Kotlarz D, Klein C, Uhlig H, Snapper SB, Gonzaga-Jauregui C, Paterson AD, McGovern DPB, Brudno M, Walters TD, Griffiths AM, Muise AM. Prevalence and Clinical Features of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases Associated With Monogenic Variants, Identified by Whole-Exome Sequencing in 1000 Children at a Single Center. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:2208-2220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Poddar U, Aggarwal A, Jayalakshmi K, Sarma MS, Srivastava A, Rawat A, Yachha SK. Higher Prevalence of Monogenic Cause Among Very Early Onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Children: Experience From a Tertiary Care Center From Northern India. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2023;29:1572-1578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Azabdaftari A, Jones KDJ, Kammermeier J, Uhlig HH. Monogenic inflammatory bowel disease-genetic variants, functional mechanisms and personalised medicine in clinical practice. Hum Genet. 2023;142:599-611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bolton C, Smillie CS, Pandey S, Elmentaite R, Wei G, Argmann C, Aschenbrenner D, James KR, McGovern DPB, Macchi M, Cho J, Shouval DS, Kammermeier J, Koletzko S, Bagalopal K, Capitani M, Cavounidis A, Pires E, Weidinger C, McCullagh J, Arkwright PD, Haller W, Siegmund B, Peters L, Jostins L, Travis SPL, Anderson CA, Snapper S, Klein C, Schadt E, Zilbauer M, Xavier R, Teichmann S, Muise AM, Regev A, Uhlig HH. An Integrated Taxonomy for Monogenic Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology. 2022;162:859-876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Uhlig HH, Schwerd T, Koletzko S, Shah N, Kammermeier J, Elkadri A, Ouahed J, Wilson DC, Travis SP, Turner D, Klein C, Snapper SB, Muise AM; COLORS in IBD Study Group and NEOPICS. The diagnostic approach to monogenic very early onset inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:990-1007.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 452] [Cited by in RCA: 474] [Article Influence: 43.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Gambineri E, Ciullini Mannurita S, Hagin D, Vignoli M, Anover-Sombke S, DeBoer S, Segundo GRS, Allenspach EJ, Favre C, Ochs HD, Torgerson TR. Clinical, Immunological, and Molecular Heterogeneity of 173 Patients With the Phenotype of Immune Dysregulation, Polyendocrinopathy, Enteropathy, X-Linked (IPEX) Syndrome. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Schwab C, Gabrysch A, Olbrich P, Patiño V, Warnatz K, Wolff D, Hoshino A, Kobayashi M, Imai K, Takagi M, Dybedal I, Haddock JA, Sansom DM, Lucena JM, Seidl M, Schmitt-Graeff A, Reiser V, Emmerich F, Frede N, Bulashevska A, Salzer U, Schubert D, Hayakawa S, Okada S, Kanariou M, Kucuk ZY, Chapdelaine H, Petruzelkova L, Sumnik Z, Sediva A, Slatter M, Arkwright PD, Cant A, Lorenz HM, Giese T, Lougaris V, Plebani A, Price C, Sullivan KE, Moutschen M, Litzman J, Freiberger T, van de Veerdonk FL, Recher M, Albert MH, Hauck F, Seneviratne S, Pachlopnik Schmid J, Kolios A, Unglik G, Klemann C, Speckmann C, Ehl S, Leichtner A, Blumberg R, Franke A, Snapper S, Zeissig S, Cunningham-Rundles C, Giulino-Roth L, Elemento O, Dückers G, Niehues T, Fronkova E, Kanderová V, Platt CD, Chou J, Chatila TA, Geha R, McDermott E, Bunn S, Kurzai M, Schulz A, Alsina L, Casals F, Deyà-Martinez A, Hambleton S, Kanegane H, Taskén K, Neth O, Grimbacher B. Phenotype, penetrance, and treatment of 133 cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4-insufficient subjects. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;142:1932-1946. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 312] [Cited by in RCA: 326] [Article Influence: 46.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Vardi I, Chermesh I, Werner L, Barel O, Freund T, McCourt C, Fisher Y, Pinsker M, Javasky E, Weiss B, Rechavi G, Hagin D, Snapper SB, Somech R, Konnikova L, Shouval DS. Monogenic Inflammatory Bowel Disease: It's Never Too Late to Make a Diagnosis. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Okada S, Asano T, Moriya K, Boisson-Dupuis S, Kobayashi M, Casanova JL, Puel A. Human STAT1 Gain-of-Function Heterozygous Mutations: Chronic Mucocutaneous Candidiasis and Type I Interferonopathy. J Clin Immunol. 2020;40:1065-1081. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 21.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Vogel TP, Leiding JW, Cooper MA, Forbes Satter LR. STAT3 gain-of-function syndrome. Front Pediatr. 2022;10:770077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Mudde ACA, Booth C, Marsh RA. Evolution of Our Understanding of XIAP Deficiency. Front Pediatr. 2021;9:660520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Fayand A, Hentgen V, Posseme C, Lacout C, Picard C, Moguelet P, Cescato M, Sbeih N, Moreau TRJ, Zhu YYJ, Charuel JL, Corneau A, Deibener-Kaminsky J, Dupuy S, Fusaro M, Hoareau B, Hovnanian A, Langlois V, Le Corre L, Maciel TT, Miskinyte S, Miyara M, Moulinet T, Perret M, Schuhmacher MH, Rignault-Bricard R, Viel S, Vinit A, Soria A, Duffy D, Launay JM, Callebert J, Herbeuval JP, Rodero MP, Georgin-Lavialle S. Successful treatment of JAK1-associated inflammatory disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2023;152:972-983. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ouahed J, Spencer E, Kotlarz D, Shouval DS, Kowalik M, Peng K, Field M, Grushkin-Lerner L, Pai SY, Bousvaros A, Cho J, Argmann C, Schadt E, Mcgovern DPB, Mokry M, Nieuwenhuis E, Clevers H, Powrie F, Uhlig H, Klein C, Muise A, Dubinsky M, Snapper SB. Very Early Onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Clinical Approach With a Focus on the Role of Genetics and Underlying Immune Deficiencies. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26:820-842. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 25.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Favier LA, Schulert GS. Mevalonate kinase deficiency: current perspectives. Appl Clin Genet. 2016;9:101-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Yokoyama Y, Yamakawa T, Ichimiya T, Kazama T, Hirayama D, Wagatsuma K, Nakase H. Gastrointestinal involvement in a patient with familial Mediterranean fever mimicking Crohn's disease: a case report. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2021;14:1103-1107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Miot C, Imai K, Imai C, Mancini AJ, Kucuk ZY, Kawai T, Nishikomori R, Ito E, Pellier I, Dupuis Girod S, Rosain J, Sasaki S, Chandrakasan S, Pachlopnik Schmid J, Okano T, Colin E, Olaya-Vargas A, Yamazaki-Nakashimada M, Qasim W, Espinosa Padilla S, Jones A, Krol A, Cole N, Jolles S, Bleesing J, Vraetz T, Gennery AR, Abinun M, Güngör T, Costa-Carvalho B, Condino-Neto A, Veys P, Holland SM, Uzel G, Moshous D, Neven B, Blanche S, Ehl S, Döffinger R, Patel SY, Puel A, Bustamante J, Gelfand EW, Casanova JL, Orange JS, Picard C. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in 29 patients hemizygous for hypomorphic IKBKG/NEMO mutations. Blood. 2017;130:1456-1467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Suri D, Rikhi R, Jindal AK, Rawat A, Sudhakar M, Vignesh P, Gupta A, Kaur A, Sharma J, Ahluwalia J, Bhatia P, Khadwal A, Raj R, Uppuluri R, Desai M, Taur P, Pandrowala AA, Gowri V, Madkaikar MR, Lashkari HP, Bhattad S, Kumar H, Verma S, Imai K, Nonoyama S, Ohara O, Chan KW, Lee PP, Lau YL, Singh S. Wiskott Aldrich Syndrome: A Multi-Institutional Experience From India. Front Immunol. 2021;12:627651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Marks DJ, Miyagi K, Rahman FZ, Novelli M, Bloom SL, Segal AW. Inflammatory bowel disease in CGD reproduces the clinicopathological features of Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:117-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Angelino G, De Angelis P, Faraci S, Rea F, Romeo EF, Torroni F, Tambucci R, Claps A, Francalanci P, Chiriaco M, Di Matteo G, Cancrini C, Palma P, D'Argenio P, Dall'Oglio L, Rossi P, Finocchi A. Inflammatory bowel disease in chronic granulomatous disease: An emerging problem over a twenty years' experience. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2017;28:801-809. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Korzenik JR, Dieckgraefe BK. Is Crohn's disease an immunodeficiency? A hypothesis suggesting possible early events in the pathogenesis of Crohn's disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:1121-1129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Mistry A, Scambler T, Parry D, Wood M, Barcenas-Morales G, Carter C, Doffinger R, Savic S. Glucose-6-Phosphatase Catalytic Subunit 3 (G6PC3) Deficiency Associated With Autoinflammatory Complications. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Boztug K, Rosenberg PS, Dorda M, Banka S, Moulton T, Curtin J, Rezaei N, Corns J, Innis JW, Avci Z, Tran HC, Pellier I, Pierani P, Fruge R, Parvaneh N, Mamishi S, Mody R, Darbyshire P, Motwani J, Murray J, Buchanan GR, Newman WG, Alter BP, Boxer LA, Donadieu J, Welte K, Klein C. Extended spectrum of human glucose-6-phosphatase catalytic subunit 3 deficiency: novel genotypes and phenotypic variability in severe congenital neutropenia. J Pediatr. 2012;160:679-683.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Moutsopoulos NM, Zerbe CS, Wild T, Dutzan N, Brenchley L, DiPasquale G, Uzel G, Axelrod KC, Lisco A, Notarangelo LD, Hajishengallis G, Notarangelo LD, Holland SM. Interleukin-12 and Interleukin-23 Blockade in Leukocyte Adhesion Deficiency Type 1. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1141-1146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Wu N, Zhang B, Wang T, Shen M, Zeng X. Case Report: A Rare Case of Autoinflammatory Phospholipase Cγ2 (PLCγ2)-Associated Antibody Deficiency and Immune Dysregulation Complicated With Gangrenous Pyoderma and Literature Review. Front Immunol. 2021;12:667430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | O'Brien KJ, Parisi X, Shelman NR, Merideth MA, Introne WJ, Heller T, Gahl WA, Malicdan MCV, Gochuico BR. Inflammatory bowel disease in Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome: a retrospective single-centre cohort study. J Intern Med. 2021;290:129-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Li Q, Lee CH, Peters LA, Mastropaolo LA, Thoeni C, Elkadri A, Schwerd T, Zhu J, Zhang B, Zhao Y, Hao K, Dinarzo A, Hoffman G, Kidd BA, Murchie R, Al Adham Z, Guo C, Kotlarz D, Cutz E, Walters TD, Shouval DS, Curran M, Dobrin R, Brodmerkel C, Snapper SB, Klein C, Brumell JH, Hu M, Nanan R, Snanter-Nanan B, Wong M, Le Deist F, Haddad E, Roifman CM, Deslandres C, Griffiths AM, Gaskin KJ, Uhlig HH, Schadt EE, Muise AM. Variants in TRIM22 That Affect NOD2 Signaling Are Associated With Very-Early-Onset Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Gastroenterology. 2016;150:1196-1207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Fujikawa H, Shimizu H, Nambu R, Takeuchi I, Matsui T, Sakamoto K, Gocho Y, Miyamoto T, Yasumi T, Yoshioka T, Arai K. Monogenic inflammatory bowel disease with STXBP2 mutations is not resolved by hematopoietic stem cell transplantation but can be alleviated via immunosuppressive drug therapy. Clin Immunol. 2023;246:109203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Lo B, Zhang K, Lu W, Zheng L, Zhang Q, Kanellopoulou C, Zhang Y, Liu Z, Fritz JM, Marsh R, Husami A, Kissell D, Nortman S, Chaturvedi V, Haines H, Young LR, Mo J, Filipovich AH, Bleesing JJ, Mustillo P, Stephens M, Rueda CM, Chougnet CA, Hoebe K, McElwee J, Hughes JD, Karakoc-Aydiner E, Matthews HF, Price S, Su HC, Rao VK, Lenardo MJ, Jordan MB. AUTOIMMUNE DISEASE. Patients with LRBA deficiency show CTLA4 loss and immune dysregulation responsive to abatacept therapy. Science. 2015;349:436-440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 439] [Cited by in RCA: 481] [Article Influence: 48.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Lo B, Fritz JM, Su HC, Uzel G, Jordan MB, Lenardo MJ. CHAI and LATAIE: new genetic diseases of CTLA-4 checkpoint insufficiency. Blood. 2016;128:1037-1042. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Abolhassani H, El-Sherbiny YM, Arumugakani G, Carter C, Richards S, Lawless D, Wood P, Buckland M, Heydarzadeh M, Aghamohammadi A, Hambleton S, Hammarström L, Burns SO, Doffinger R, Savic S. Expanding Clinical Phenotype and Novel Insights into the Pathogenesis of ICOS Deficiency. J Clin Immunol. 2020;40:277-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Schepp J, Chou J, Skrabl-Baumgartner A, Arkwright PD, Engelhardt KR, Hambleton S, Morio T, Röther E, Warnatz K, Geha R, Grimbacher B. 14 Years after Discovery: Clinical Follow-up on 15 Patients with Inducible Co-Stimulator Deficiency. Front Immunol. 2017;8:964. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Cagdas D, Mayr D, Baris S, Worley L, Langley DB, Metin A, Aytekin ES, Atan R, Kasap N, Bal SK, Dmytrus J, Heredia RJ, Karasu G, Torun SH, Toyran M, Karakoc-Aydiner E, Christ D, Kuskonmaz B, Uçkan-Çetinkaya D, Uner A, Oberndorfer F, Schiefer AI, Uzel G, Deenick EK, Keller B, Warnatz K, Neven B, Durandy A, Sanal O, Ma CS, Özen A, Stepensky P, Tezcan I, Boztug K, Tangye SG. Genomic Spectrum and Phenotypic Heterogeneity of Human IL-21 Receptor Deficiency. J Clin Immunol. 2021;41:1272-1290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Jesus AA, Duarte AJ, Oliveira JB. Autoimmunity in hyper-IgM syndrome. J Clin Immunol. 2008;28 Suppl 1:S62-S66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Hervé M, Isnardi I, Ng YS, Bussel JB, Ochs HD, Cunningham-Rundles C, Meffre E. CD40 ligand and MHC class II expression are essential for human peripheral B cell tolerance. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1583-1593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Khan F, Person H, Dekio F, Ogawa M, Ho HE, Dunkin D, Secord E, Cunningham-Rundles C, Ward SC. Crohn's-like Enteritis in X-Linked Agammaglobulinemia: A Case Series and Systematic Review. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9:3466-3478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Mao L, Kitani A, Hiejima E, Montgomery-Recht K, Zhou W, Fuss I, Wiestner A, Strober W. Bruton tyrosine kinase deficiency augments NLRP3 inflammasome activation and causes IL-1β-mediated colitis. J Clin Invest. 2020;130:1793-1807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Catucci M, Castiello MC, Pala F, Bosticardo M, Villa A. Autoimmunity in wiskott-Aldrich syndrome: an unsolved enigma. Front Immunol. 2012;3:209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Kahr WH, Pluthero FG, Elkadri A, Warner N, Drobac M, Chen CH, Lo RW, Li L, Li R, Li Q, Thoeni C, Pan J, Leung G, Lara-Corrales I, Murchie R, Cutz E, Laxer RM, Upton J, Roifman CM, Yeung RS, Brumell JH, Muise AM. Loss of the Arp2/3 complex component ARPC1B causes platelet abnormalities and predisposes to inflammatory disease. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Engelhardt KR, Gertz ME, Keles S, Schäffer AA, Sigmund EC, Glocker C, Saghafi S, Pourpak Z, Ceja R, Sassi A, Graham LE, Massaad MJ, Mellouli F, Ben-Mustapha I, Khemiri M, Kilic SS, Etzioni A, Freeman AF, Thiel J, Schulze I, Al-Herz W, Metin A, Sanal Ö, Tezcan I, Yeganeh M, Niehues T, Dueckers G, Weinspach S, Patiroglu T, Unal E, Dasouki M, Yilmaz M, Genel F, Aytekin C, Kutukculer N, Somer A, Kilic M, Reisli I, Camcioglu Y, Gennery AR, Cant AJ, Jones A, Gaspar BH, Arkwright PD, Pietrogrande MC, Baz Z, Al-Tamemi S, Lougaris V, Lefranc G, Megarbane A, Boutros J, Galal N, Bejaoui M, Barbouche MR, Geha RS, Chatila TA, Grimbacher B. The extended clinical phenotype of 64 patients with dedicator of cytokinesis 8 deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136:402-412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Sanal O, Jing H, Ozgur T, Ayvaz D, Strauss-Albee DM, Ersoy-Evans S, Tezcan I, Turkkani G, Matthews HF, Haliloglu G, Yuce A, Yalcin B, Gokoz O, Oguz KK, Su HC. Additional diverse findings expand the clinical presentation of DOCK8 deficiency. J Clin Immunol. 2012;32:698-708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Tessarin G, Rossi S, Baronio M, Gazzurelli L, Colpani M, Benvenuto A, Zunica F, Cardinale F, Martire B, Brescia L, Costagliola G, Luti L, Casazza G, Menconi MC, Saettini F, Palumbo L, Girelli MF, Badolato R, Lanzi G, Chiarini M, Moratto D, Meini A, Giliani S, Bondioni MP, Plebani A, Lougaris V. Activated Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase Delta Syndrome 1: Clinical and Immunological Data from an Italian Cohort of Patients. J Clin Med. 2020;9:3335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Justiz-Vaillant AA, Gopaul D, Akpaka PE, Soodeen S, Arozarena Fundora R. Severe Combined Immunodeficiency-Classification, Microbiology Association and Treatment. Microorganisms. 2023;11:1589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Felgentreff K, Perez-Becker R, Speckmann C, Schwarz K, Kalwak K, Markelj G, Avcin T, Qasim W, Davies EG, Niehues T, Ehl S. Clinical and immunological manifestations of patients with atypical severe combined immunodeficiency. Clin Immunol. 2011;141:73-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Sun B, Chen Q, Wang Y, Liu D, Hou J, Wang W, Ying W, Hui X, Zhou Q, Sun J, Wang X. LIG4 syndrome: clinical and molecular characterization in a Chinese cohort. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2020;15:131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 56. | Rowe JH, Delmonte OM, Keles S, Stadinski BD, Dobbs AK, Henderson LA, Yamazaki Y, Allende LM, Bonilla FA, Gonzalez-Granado LI, Celikbilek Celik S, Guner SN, Kapakli H, Yee C, Pai SY, Huseby ES, Reisli I, Regueiro JR, Notarangelo LD. Patients with CD3G mutations reveal a role for human CD3γ in T(reg) diversity and suppressive function. Blood. 2018;131:2335-2344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Shirkani A, Shahrooei M, Azizi G, Rokni-Zadeh H, Abolhassani H, Farrokhi S, Frans G, Bossuyt X, Aghamohammadi A. Novel Mutation of ZAP-70-related Combined Immunodeficiency: First Case from the National Iranian Registry and Review of the Literature. Immunol Invest. 2017;46:70-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Ghadimi S, Jamee M, Abolhassani H, Parvaneh N, Rezaei N, Delavari S, Sadeghi-Shabestari M, Tabatabaei SR, Fahimzad A, Armin S, Chavoshzadeh Z, Sharafian S. Demographic, clinical, immunological, and molecular features of iranian national cohort of patients with defect in DCLRE1C gene. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2023;19:13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Kotlarz D, Marquardt B, Barøy T, Lee WS, Konnikova L, Hollizeck S, Magg T, Lehle AS, Walz C, Borggraefe I, Hauck F, Bufler P, Conca R, Wall SM, Schumacher EM, Misceo D, Frengen E, Bentsen BS, Uhlig HH, Hopfner KP, Muise AM, Snapper SB, Strømme P, Klein C. Human TGF-β1 deficiency causes severe inflammatory bowel disease and encephalopathy. Nat Genet. 2018;50:344-348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Naviglio S, Arrigo S, Martelossi S, Villanacci V, Tommasini A, Loganes C, Fabretto A, Vignola S, Lonardi S, Ventura A. Severe inflammatory bowel disease associated with congenital alteration of transforming growth factor beta signaling. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:770-774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Sultan M, Adawi M, Kol N, McCourt B, Adawi I, Baram L, Tal N, Werner L, Lev A, Snapper SB, Barel O, Konnikova L, Somech R, Shouval DS. RIPK1 mutations causing infantile-onset IBD with inflammatory and fistulizing features. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1041315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Glocker EO, Kotlarz D, Boztug K, Gertz EM, Schäffer AA, Noyan F, Perro M, Diestelhorst J, Allroth A, Murugan D, Hätscher N, Pfeifer D, Sykora KW, Sauer M, Kreipe H, Lacher M, Nustede R, Woellner C, Baumann U, Salzer U, Koletzko S, Shah N, Segal AW, Sauerbrey A, Buderus S, Snapper SB, Grimbacher B, Klein C. Inflammatory bowel disease and mutations affecting the interleukin-10 receptor. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2033-2045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1149] [Cited by in RCA: 1086] [Article Influence: 67.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Consonni F, Ciullini Mannurita S, Gambineri E. Atypical Presentations of IPEX: Expect the Unexpected. Front Pediatr. 2021;9:643094. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Caudy AA, Reddy ST, Chatila T, Atkinson JP, Verbsky JW. CD25 deficiency causes an immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked-like syndrome, and defective IL-10 expression from CD4 lymphocytes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:482-487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 307] [Cited by in RCA: 296] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Jardine S, Dhingani N, Muise AM. TTC7A: Steward of Intestinal Health. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;7:555-570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Imoto I, Saito M, Suga K, Kohmoto T, Otsu M, Horiuchi K, Nakayama H, Higashiyama S, Sugimoto M, Sasaki A, Homma Y, Shono M, Nakagawa R, Hayabuchi Y, Tange S, Kagami S, Masuda K. Functionally confirmed compound heterozygous ADAM17 missense loss-of-function variants cause neonatal inflammatory skin and bowel disease 1. Sci Rep. 2021;11:9552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Zimmer KP, Schumann H, Mecklenbeck S, Bruckner-Tuderman L. Esophageal stenosis in childhood: dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa without skin blistering due to collagen VII mutations. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:220-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Roda Â, Travassos AR, Soares-de-Almeida L, Has C. Kindler syndrome in a patient with colitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis: coincidence or association? Dermatol Online J. 2018;24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Fiskerstrand T, Arshad N, Haukanes BI, Tronstad RR, Pham KD, Johansson S, Håvik B, Tønder SL, Levy SE, Brackman D, Boman H, Biswas KH, Apold J, Hovdenak N, Visweswariah SS, Knappskog PM. Familial diarrhea syndrome caused by an activating GUCY2C mutation. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1586-1595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |