Published online Aug 18, 2018. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v9.i8.105

Peer-review started: March 6, 2018

First decision: March 23, 2018

Revised: May 17, 2018

Accepted: May 23, 2018

Article in press: May 23, 2018

Published online: August 18, 2018

Processing time: 167 Days and 14.6 Hours

To examine whether opioid dependence or abuse has an effect on opioid utilization after anatomic or reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA).

All anatomic TSA (ICD-9 81.80) and reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) (ICD-9 81.88) procedures from 2007 to 2015 were queried from within the Humana claims database utilizing the PearlDiver supercomputer (Colorado Springs, CO). Study groups were formed based on the presence or absence of a previous history of opioid dependence (ICD-9 304.00 and 304.03) or abuse (ICD-9 305.50 and 305.53). Opioid utilization among the groups was tracked monthly up to 1 year post-operatively utilizing National Drug Codes. A secondary analysis was performed to determine risk factors for pre-operative opioid dependence or abuse.

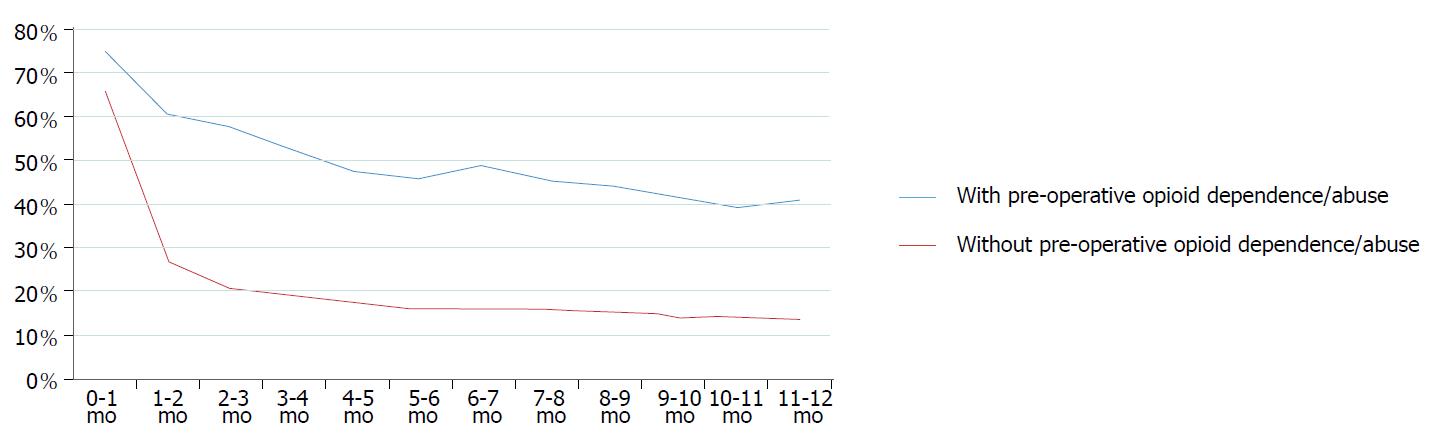

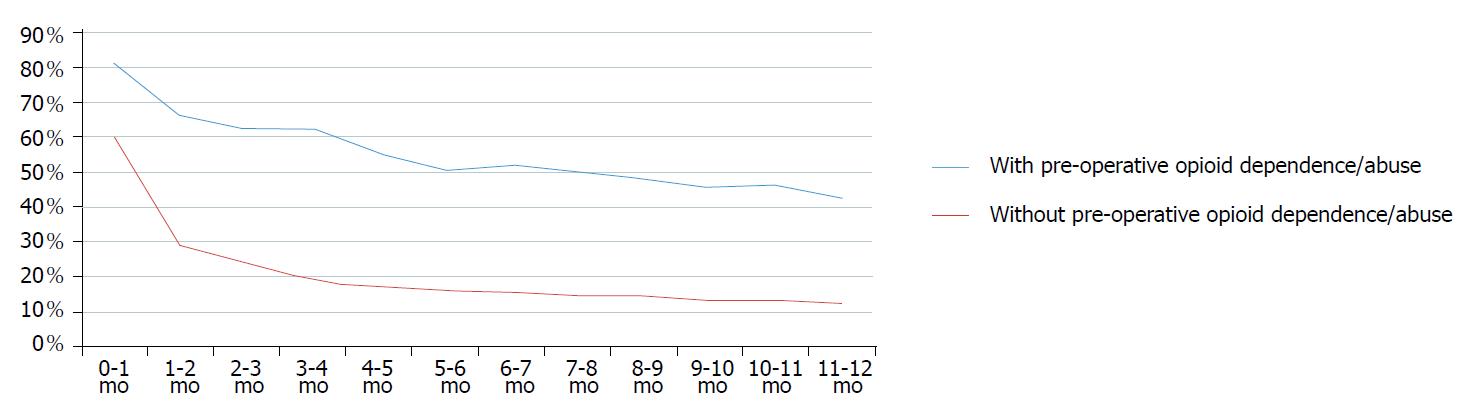

Two percent of TSA (157 out of 7838) and 3% of RSA (206 out of 6920) patients had a history of opioid dependence or abuse. For both TSA and RSA, opioid utilization was significantly higher in opioid dependent patients at all post-operative intervals (P < 0.01) although the incidence of opioid use among groups was similar within the first post-operative month. After TSA, opioid dependent patients were over twice as likely to fill opioid prescriptions during the post-operative months 1-12. Following RSA, opioid dependent patients were over 3 times as likely to utilize opioids from months 3-12. Age less than 65 years, history of mood disorder, and history of chronic pain were significant risk factors for pre-operative opioid dependence/abuse in patients who underwent TSA or RSA.

Following shoulder arthroplasty, opioid use between opioid-dependent and non-dependent patients is similar within the first post-operative month but is greater among opioid-dependent patients from months 2-12.

Core tip: A retrospective analysis of the Humana claims determined that patients with pre-operative opioid dependence or abuse had higher post-operative opioid utilization after anatomic total shoulder arthroplasty and reverse shoulder arthroplasty. Younger age, mood disorders, and chronic pain diagnoses were significant risk factors for pre-operative opioid dependence or abuse.

- Citation: Berglund DD, Rosas S, Kurowicki J, Mijic D, Levy JC. Effect of opioid dependence or abuse on opioid utilization after shoulder arthroplasty. World J Orthop 2018; 9(8): 105-111

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v9/i8/105.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v9.i8.105

Opioid analgesics have proven to be effective in treating severe pain. However, increasing utilization along with highly addictive properties of opioid medications has led to significant societal consequences. The utilization of opioids for analgesia in the United States increased substantially from the late 1990’s to the early 2010’s[1,2]. In the United States opioid consumption is significantly higher than any other country[3,4] and this has in turn led to an increase in opioid abuse and dependence among patients. Opioid utilization has a profound impact on the practice of orthopaedics as orthopaedic surgeons are the 3rd highest prescribers of opioid medications among physicians[5]. Opioid dependence or abuse among patients undergoing elective orthopedic surgery has increased by 152% from 2002 to 2011 and has been associated with increased inpatient morbidity and mortality[6].

Increasing rates of opioid dependence or abuse has a significant negative impact on patients undergoing shoulder arthroplasty as pre-operative opioid use has been associated with worse patient-reported outcomes post-operatively[7,8]. Previous national database studies have shown that patients using opioids prior to knee arthroplasty or rotator cuff repair are more likely to continue using opioids for prolonged post-operative periods[9,10]. However, no study to date has analyzed the impact of diagnosed opioid dependence or abuse on opioid utilization after shoulder arthroplasty. The purpose of the current study is to examine whether diagnosed pre-operative opioid dependence or abuse has an effect on opioid utilization following total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA) or reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA). Our hypothesis was that patients with pre-operative opioid abuse or dependence would have greater opioid utilization. Secondarily, we sought to evaluate potential risk factors for pre-operative opioid dependence or abuse within this patient population.

The PearlDiver supercomputer (Pearldiver Inc, Colorado Springs, CO) was utilized to query the Humana Inc administrative claims database. This database contains claims data from 2007 through 2015 for over 20 million patients that are insured privately/commercially or through Medicare/Medicare Advantage. The data retrieved from the database is retrospective, publicly available, and is complaint with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). This study was therefore deemed exempt from institutional review board review.

Patients who underwent anatomic TSA and RSA were identified using International Classification of Disease Ninth Edition (ICD-9) codes 81.80 and 81.88, respectively. Separate analyses were performed for each arthroplasty type. Patients were divided into study groups based on whether there was a history of diagnosed opioid dependence or abuse prior to surgery. This was delineated using ICD-9 codes for opioid dependence (304.00 and 304.03) and opioid abuse (305.50 and 305.53). Patients who received a brachial plexus nerve block on the day of surgery were identified using the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code 64415 and the proportion of patients receiving nerve blocks were compared between groups.

Generic drug codes for commonly prescribed opioid medications (Table 1) were used to determine the number of patients within each study group that filled at least one opioid prescription within specific post-operative time periods. These codes are mapped to eleven-digit National Drug Codes (NDC) on patient charging records. The percent of patients filling opioid prescriptions was compared between patients with and without a history of opioid dependence or abuse for both TSA and RSA. This was performed on a month-by-month basis up to one year post-operatively.

| Opioid medication | Generic drug codes |

| Oxycodone | 101126, 101215, 106757, 108546, 111094, 107000, 109518, 100548, 100504, 110286, 109192, 106437 |

| Hydrocodone | 106414, 112157, 101854, 100055, 110070, 105295, 112625, 102382, 101434, 109398, 110812, 100358, 101802, 108359, 106104, 106326, 106622, 107601, 103995, 111636, 106030, 106747, 101805, 110605, 108113, 112007 |

| Morphine sulfate | 104592, 106367, 108034, 104962, 100074, 103380, 108114, 110174, 112832 |

| Codeine | 101623, 100873, 107990, 103275, 104787, 104710, 107214, 112297, 104491, 112574, 112774, 108218, 101073, 107402, 103943, 107406, 104952, 108825, 102621, 110215, 101274, 109769, 105010, 105460, 111188, 107202, 112555, 104895, 108556, 102273, 107506, 110492, 110760, 112140, 107410, 103069, 109078, 101383, 109320, 104915, 112523, 100351, 111016, 108443, 106918, 105070, 104040, 109446, 111749, 108445, 108480, 112775, 105654, 110799, 109752, 100679, 109086, 108889, 110743, 106810, 102890, 110671 |

| Fentanyl | 100599, 104678, 101119, 103260, 100142 |

| Hydromorphone | 101111, 100978 |

| Meperidine | 101505, 101784, 112026 |

| Methadone hydrochloride | 100319 |

| Oxymorphone hydrochloride | 101242 |

A secondary analysis was performed to determine risk factors for pre-operative opioid dependence or abuse among patients undergoing TSA or RSA. The relative risk of opioid dependence/abuse was determined for gender, age, the presence of chronic pain (ICD-9 codes 338.29, 338.4, 338.21, 338.28, and 338.22) and mood disorder (ICD-9 codes 296.00 and 296.99) diagnoses. Charlson Comorbidity Index was also compared for patients with opioid dependence/abuse vs those without.

Statistical analysis was conducted with descriptive and comparative evaluations based on data type (continuous vs categorical). Incidences were used to calculate relative risk rations and 95%CIs through univariate regressions. Age (younger or older than 65), pre-operative opioid abuse (present or not) and the presence of chronic pain (defined as present or not) were dichotomized into 2 groups for comparison. Statistical analysis was conducted with SPSS (version 20, IBM corporation, Armonk, NY, United States).

Our query returned 7838 patients (3417 male and 4421 female) that underwent TSA between 2007 and 2015. Of that, 157 patients (2.0%) had diagnoses of opioid dependence or abuse prior to surgery and were placed in the opioid dependence/abuse group while the remainder of patients, 7681 (98.0%) without diagnoses of opioid dependence or abuse were placed in the non-opioid dependent group. The proportion of patients receiving a brachial plexus nerve block was not significantly different between patients with and without opioid dependence or abuse (P = 0.199, Table 2).

| With pre-op opioid dependence/abuse | Without pre-op opioid dependence/abuse | P-value | |

| TSA | 92 (58.60) | 4105 (53.44) | 0.199 |

| RSA | 108 (52.43) | 3461 (51.55) | 0.803 |

Within the first post-operative month, 75.16% of patients with opioid dependence/abuse and 66.01% of patients without opioid dependence/abuse filled at least one opioid prescription. The incidence of opioid use in the opioid-dependent group decreased to 60.51% from 1-2 mo and subsequently continued to decrease until 6 mo post-operatively where it plateaued. Opioid use ranged from 39.49%-48.41% from 6-12 mo in the opioid-dependent group. For patients without a history of opioid dependence or abuse, opioid use decreased to 26.92% after the first month and then slowly decreased from post-operative months 2-12 (range 13.74%-20.82%). Opioid use among patients with a history of dependence/abuse was significantly greater than in the non-opioid dependent patients at all postoperative time intervals (P < 0.01). Within the first post-operative month, patients with a history of opioid dependence/abuse were only slightly more likely to use opioids (RR = 1.14, 95%CI: 1.04-1.25). However, from months 1-12 they were over twice as likely to fill opioid prescriptions (RR ranged 2.25-3.00, 95%CI: 1.97-3.61) (Table 3 and Figure 1).

| TSA | RSA | |||||

| Post-operative interval | RR | 95%CI | P value | RR | 95%CI | P value |

| 0-1 mo | 1.14 | 1.04-1.25 | 0.005 | 1.36 | 1.27-1.45 | < 0.001 |

| 1-2 mo | 2.25 | 1.97-2.56 | < 0.0001 | 2.28 | 2.06-2.53 | < 0.001 |

| 2-3 mo | 2.78 | 2.42-3.20 | < 0.0001 | 2.69 | 2.40-3.02 | < 0.001 |

| 3-4 mo | 2.80 | 2.39-3.27 | < 0.0001 | 3.20 | 2.85-3.60 | < 0.001 |

| 4-5 mo | 2.78 | 2.34-3.30 | < 0.0001 | 3.23 | 2.82-3.69 | < 0.001 |

| 5-6 mo | 2.84 | 2.38-3.40 | < 0.0001 | 3.09 | 2.67-3.57 | < 0.001 |

| 6-7 mo | 3.00 | 2.54-3.56 | < 0.0001 | 3.26 | 2.82-3.75 | < 0.001 |

| 7-8 mo | 2.87 | 2.40-3.43 | < 0.0001 | 3.34 | 2.87-3.88 | < 0.001 |

| 8-9 mo | 2.88 | 2.39-3.46 | < 0.0001 | 3.30 | 2.83-3.85 | < 0.001 |

| 9-10 mo | 2.90 | 2.39-3.52 | < 0.0001 | 3.47 | 2.95-4.08 | < 0.001 |

| 10-11 mo | 2.81 | 2.30-3.44 | < 0.0001 | 3.50 | 2.98-4.10 | < 0.001 |

| 11-12 mo | 2.97 | 2.44-3.61 | < 0.0001 | 3.36 | 2.83-3.98 | < 0.001 |

Analysis of risk factors showed that patients less than 65 years old (RR = 2.12, 95%CI: 1.46-3.08, P = 0.0001), patients with previous diagnosis of a mood disorder (RR = 6.70, CI: 4.92-9.11, P < 0.0001), and patients with diagnosis of chronic pain (RR = 10.31, 95%CI: 7.51-14.17, P <0.0001) were more likely to have abused opioids or be opioid dependent prior to TSA surgery. Gender did not have an impact on the risk for opioid dependence/abuse prior to surgery (RR = 1.06 for female gender, 95%CI: 0.78-1.46, P = 0.69). The mean CCI was significantly higher (4 ± 3.71 vs 2 ± 2.73, P < 0.001) in patients with a history of opioid dependence/abuse (Table 4).

| TSA | RSA | |||||

| Variable | RR | 95%CI | P value | RR | 95%CI | P value |

| Female | 1.07 | 0.78-1.46 | 0.691 | 1.3 | 0.96-1.75 | 0.085 |

| Age < 65 | 2.12 | 1.46-3.08 | 0.000 | 1.6 | 1.06-2.41 | 0.024 |

| Mood disorder | 6.70 | 4.92-9.11 | < 0.0001 | 5.27 | 4.04-6.87 | < 0.0001 |

| Chronic pain | 10.31 | 7.51-14.17 | < 0.0001 | 10.10 | 7.53-13.57 | < 0.0001 |

Among the 6920 patients that underwent RSA within the study period, 206 (3.0%) had a previous diagnosis of opioid dependence/abuse and 6714 (97.0%) did not. The proportion of patients receiving a brachial plexus block did not differ significantly between groups (P = 0.803, Table 2).

Eighty-one point five five percent of patients in the opioid-dependent group filled opioid prescriptions within the first post-operative month. This percentage fell to 66.50% after the first month and gradually decreased to 42.72% from 1 to 12 mo post-operatively (range 42.72%-66.50%). Of the patients in the non-opioid dependent group, 60.05% filled prescriptions within the first post-operative month. This percentage quickly fell to less than 30% after the first month and then slowly decreased from 4 to 12 mo (range 12.72%-17.16%). Opioid use was significantly higher for patients with previously diagnosed dependence/abuse at all post-operative intervals (P < 0.001). Within the first post-operative month, opioid dependent patients were slightly more likely to fill opioid prescriptions (RR = 1.36, 95%CI: 1.27-1.45). However, they were over 3 times as likely to use opioids during post-operative months 3-12 (RR ranged 3.09-3.50, 95%CI: 2.67-4.10) (Table 3 and Figure 2).

Age less than 65 years (RR = 1.60, 95%CI: 1.06-2.41, P = 0.0240), prior diagnosis of mood disorder (RR = 5.27, 95%CI: 4.04-6.87, P < 0.0001), and chronic pain diagnosis (RR = 10.10, 95%CI: 7.53-13.57, P < 0.0001) were significant risk factors for opioid dependence or abuse prior to RSA. Female patients were slightly more likely to have pre-operative opioid dependence/abuse (RR = 1.30, 95%CI: 0.96-1.75) but this result was not statistically significant (P = 0.0848). The mean CCI was significantly higher for the opioid dependent group (5 ± 3.85 vs 3 ± 3.20, P = 0.001) (Table 4).

The results of the current study show that, following TSA and RSA, both opioid dependent and non-opioid dependent patients had similar opioid use within the first post-operative month. However, opioid use was much more prevalent among patients previously diagnosed with opioid dependence beyond the initial post-operative period. Younger age, mood disorders, and chronic pain diagnoses were significant risk factors for pre-operatively diagnosed opioid dependence or abuse.

Several previous studies utilizing national databases have analyzed the impact of pre-operative opioid use on post-operative use after orthopaedic surgery. Bedard et al[9] found that pre-operative opioid use was a strong predictor of post-operative use following total knee arthroplasty. The incidences of opioid use at post-operative months 2-12 for “opioid users” in their study were similar to those for opioid-dependent patients in the current study. However, “non-opioid users” in their study had lower overall incidences of opioid use compared to the non-opioid dependent patients in the current study. This discrepancy may be related to differences in the specific opioid medications included in each analysis. “All common oral and transdermal opioids” were included in Bedard’s analysis with the exception of tramadol. However, the authors did not disclose detailed information on the specific medications included. It is therefore possible that post-operative opioid use was under-reported in the “non-opioid users”.

Westermann et al[10] utilized the Humana dataset to analyze opioid use following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair (RCR). They found that patients using opioids within 3 mo prior to surgery were more like to fill opioid prescriptions post-operatively. Following the first post-operative month, the monthly incidences of opioid use for both opioid and non-opioid users was lower than opioid-dependent and non-opioid dependent patients in the current study, respectively. Similar to Bedard et al[9], the specific opioid medications tracked in Westermann's analysis may have contributed to this difference as the drugs analyzed in their study were not specified.

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) currently has no clinical practice guidelines recommending for or against the use of opioids following shoulder arthroplasty. Yet, opioid utilization is common following these procedures and the negative effects of pre-operative use on post-operative outcomes are clear[7,8]. In a recent Information Statement, the AAOS has advocated for the development of standardized opioid prescription protocols that include limits on prescription number and duration[11]. We support this statement and recommend that orthopaedic surgeons collaborate with primary care physicians and pain specialists as a part of a multidisciplinary team in the development these protocols. Based on the findings of our study, it would be prudent for physicians to closely monitor opioid utilization for patients with a history of opioid dependence or abuse. The current study clearly demonstrates that patients with a history of opioid dependence or abuse are at increased risk for prolonged postoperative opioid use. Furthermore, use of a risk-assessment tool for behaviors associated with prolonged opioid use[12] could be utilized to help identify risk factors for opioid dependence such as mood disorders and chronic pain diagnoses. As demonstrated in the current study, patients with risk factors such as mood disorder or chronic pain diagnosis are more prone to opioid dependence/abuse and, subsequently, to greater post-operative opioid use.

A key strength of the current study rests in the analysis of patients with any previous history of diagnosed opioid dependence or abuse, whereas the studies by Bedard[9] and Westermann[10] focused on patients who filled an opioid prescription within 3 mo prior to surgery. It is quite possible that patients assessed in other studies did not have diagnosis of opioid dependence or abuse, and received opioids for temporary pain management prior to surgery. This likely explains the discrepancy between the percentages of opioid users in their studies (31% for THA, 43% for RCR) and the percentages of opioid dependent patients in our study (2% for TSA, 3% for RSA). It is our opinion that investigating patients with a history of diagnosed opioid dependence/abuse is a more meaningful analysis. While it is still possible that patients with previously diagnosed opioid dependence/abuse may not have been taking opioids immediately before surgery, having a history of diagnosed opioid dependence/abuse is a patient characteristic that can have lasting negative implications on postoperative outcomes even after cessation of opioid use[13]. During preoperative assessment, orthopedic surgeons should be encouraged to investigate any history of opioid dependence/abuse, however remote. As shown in the current study, these patients are at a higher risk for prolonged post-operative opioid use.

Certain limitations exist for the current study. First of all, the accuracy of data within large national databases such as the Humana claims dataset is dependent on proper coding. Errors in documentation have the potential to skew results. Secondly, previous studies have shown that brachial plexus nerve blocks prior to shoulder surgery decrease postoperative opioid utilization[14,15], thus acting as a potential confounding variable. However, the proportion of patients receiving brachial plexus nerve blocks in this study was equivalent between study groups (Table 2) and thus did not likely affect the results. Third, the incidence of diagnosed opioid dependence/abuse is quite low. However, the use of a large national database is beneficial in providing the power required to show significant differences in smaller patient populations. Finally, wide standard deviations existed for CCI. For both TSA and RSA, the CCI standard deviation in patients without opioid dependence/abuse was greater than the mean. The difference in CCI between patients with and without opioid dependence/abuse history was significant but the wide distribution of CCI scores must be taken into account when determining patients’ risk for opioid dependence/abuse.

In patients undergoing TSA and RSA, opioid use was similar within the first post-operative month for patients with and without a history of diagnosed opioid dependence/abuse. However, opioid use was much more prevalent among diagnosed opioid dependent patients from months 2-12. Younger age, mood disorders, and chronic pain diagnoses were significant risk factors for pre-operative opioid dependence or abuse. We recommend that orthopaedic surgeons carefully examine patients’ opioid use history, as this may have a significant impact on prolonged post-operative opioid use after shoulder arthroplasty and the overall postoperative outcomes.

While opioid medications have proven an effective method of analgesia after orthopaedic surgery, increased utilization of these medications in the United States has led to an opioid epidemic with higher levels of opioid dependence and abuse. Opioid dependence and abuse have been linked to worse outcomes after shoulder arthroplasty. Previous studies have shown that patients using opioids prior to total knee arthroplasty or rotator cuff repair have a greater risk of prolonged postoperative use. However, no study to our knowledge has analyzed the effect of diagnosed dependence or abuse on postoperative opioid utilization after shoulder arthroplasty.

With opioid dependence and abuse rapidly increasing in the United States, it is imperative to determine their effects on postoperative opioid use. The current study addresses this question within the setting of shoulder arthroplasty, as orthopedic surgeons have been shown to be one of the largest prescribers of opioid medications. The knowledge gained from this study may impact providers’ decisions to proceed with elective surgery, as opioid dependent patients are more likely to continue opioid use postoperatively and therefore perpetuate their dependence on opioid medications. The study will likely encourage future research pertaining to postoperative opioid monitoring in opioid dependent patients as well as the use of risk assessment tools for opioid dependence or abuse.

The purpose of this study was to analyze the impact of diagnosed opioid dependence or abuse on postoperative opioid utilization after anatomic and reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA). Furthermore, the authors sought to identify risk factors for preoperative opioid dependence or abuse. The study results highlight the importance of future research on the topic of identifying these risk factors, preventing the development of operative opioid dependence or abuse prior to orthopaedic surgery, and subsequently limiting postoperative opioid utilization.

Patients who underwent anatomic (RSA) or reverse TSA were identified from within the Humana claims database and were stratified into groups based on whether they had a history of opioid dependence or abuse. Postoperative opioid utilization was tracked on a month-by-month basis up to one year after surgery and was compared between the groups. A secondary analysis was performed to determine risk factors for preoperative opioid dependence or abuse.

Patients with a history of opioid dependence or abuse had significantly higher opioid utilization at all postoperative intervals after both TSA and RSA (P < 0.01), although the difference was not as prominent within the first postoperative month. Furthermore, age less than 65 years, history of mood disorder, and history of chronic pain were found to be significant risk factors for pre-operative opioid dependence or abuse. These results emphasize the importance of identifying patients preoperatively with a history of opioid dependence/abuse, or risk factors for developing opioid dependence/abuse, so that prolonged postoperative opioid use may be prevented. Further research is needed to determine specifically how these risk factors lead to opioid dependence and for establishing consistent postoperative opioid prescription protocols for shoulder arthroplasty.

New findings of the current study include that patients with a history of opioid dependence or abuse prior to shoulder arthroplasty are at least twice as likely to remain on opioids after TSA or RSA. Patients with risk factors such as mood disorders or chronic pain diagnoses were found to be more prone to opioid dependence/abuse and the authors theorize that this subsequently leads to greater post-operative opioid use. The study provided a summarization of the current knowledge by offering similar findings to previous studies showing that opioid use prior to orthopaedic procedures leads to increased postoperative use. It offered original insights into the current knowledge by focusing on patients with diagnosed opioid dependence or abuse and establishing risk factors for these diagnoses. It proposed a new hypothesis that patients with pre-operative opioid abuse or dependence would have greater opioid utilization after TSA. The authors utilized methodology that identified preoperative opioid dependence or abuse, along with its risk factors, through the use of ICD-9 codes and tracked postoperative utilization through National Drug Codes. The authors found the new phenomena of significantly greater postoperative opioid utilization in opioid dependent patients after shoulder arthroplasty, though opioid use was similar within the first postoperative month. The study experiments confirmed the hypothesis that patients with previously diagnosed opioid dependence or abuse would have greater postoperative opioid utilization and that other factors such as mood disorders and chronic pain diagnoses are associated with opioid dependence/abuse. These findings imply that opioid utilization in opioid dependent patients, or those with risk factors for opioid dependence/abuse, must be monitored closely after shoulder arthroplasty in order to prevent prolonged use. Steps should be taken to implement postoperative opioid protocols for shoulder arthroplasty.

Patients with a history of opioid dependence or abuse are at a higher risk of increased postoperative opioid utilization after shoulder arthroplasty. Future research should be directed at the implementation of postoperative opioid protocols and the use of risk assessment calculators for opioid dependence.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Kurosawa S S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Tan WW

| 1. | Atluri S, Sudarshan G, Manchikanti L. Assessment of the trends in medical use and misuse of opioid analgesics from 2004 to 2011. Pain Physician. 2014;17:E119-E128. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Gilson AM, Ryan KM, Joranson DE, Dahl JL. A reassessment of trends in the medical use and abuse of opioid analgesics and implications for diversion control: 1997-2002. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;28:176-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 246] [Cited by in RCA: 245] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Fischer B, Keates A, Bühringer G, Reimer J, Rehm J. Non-medical use of prescription opioids and prescription opioid-related harms: why so markedly higher in North America compared to the rest of the world? Addiction. 2014;109:177-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lindenhovius AL, Helmerhorst GT, Schnellen AC, Vrahas M, Ring D, Kloen P. Differences in prescription of narcotic pain medication after operative treatment of hip and ankle fractures in the United States and The Netherlands. J Trauma. 2009;67:160-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Volkow ND, McLellan TA, Cotto JH, Karithanom M, Weiss SR. Characteristics of opioid prescriptions in 2009. JAMA. 2011;305:1299-1301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 687] [Cited by in RCA: 676] [Article Influence: 48.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Menendez ME, Ring D, Bateman BT. Preoperative Opioid Misuse is Associated With Increased Morbidity and Mortality After Elective Orthopaedic Surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:2402-2412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 245] [Cited by in RCA: 288] [Article Influence: 28.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Morris BJ, Laughlin MS, Elkousy HA, Gartsman GM, Edwards TB. Preoperative opioid use and outcomes after reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24:11-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Morris BJ, Sciascia AD, Jacobs CA, Edwards TB. Preoperative opioid use associated with worse outcomes after anatomic shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25:619-623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bedard NA, Pugely AJ, Westermann RW, Duchman KR, Glass NA, Callaghan JJ. Opioid Use After Total Knee Arthroplasty: Trends and Risk Factors for Prolonged Use. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32:2390-2394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 24.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Westermann RW, Anthony CA, Bedard N, Glass N, Bollier M, Hettrich CM, Wolf BR. Opioid Consumption After Rotator Cuff Repair. Arthroscopy. 2017;33:1467-1472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Opioid Use, Misuse, and Abuse in Orthopaedic Practice. 2015;Information Statement 1045. |

| 12. | Webster LR, Webster RM. Predicting aberrant behaviors in opioid-treated patients: preliminary validation of the Opioid Risk Tool. Pain Med. 2005;6:432-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 681] [Cited by in RCA: 661] [Article Influence: 34.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ren ZY, Shi J, Epstein DH, Wang J, Lu L. Abnormal pain response in pain-sensitive opiate addicts after prolonged abstinence predicts increased drug craving. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2009;204:423-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Abdallah FW, Halpern SH, Aoyama K, Brull R. Will the Real Benefits of Single-Shot Interscalene Block Please Stand Up? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Anesth Analg. 2015;120:1114-1129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chen HP, Shen SJ, Tsai HI, Kao SC, Yu HP. Effects of Interscalene Nerve Block for Postoperative Pain Management in Patients after Shoulder Surgery. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:902745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |