Published online Jan 18, 2015. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v6.i1.150

Peer-review started: March 31, 2014

First decision: May 14, 2014

Revised: May 30, 2014

Accepted: August 27, 2014

Article in press: August 29, 2014

Published online: January 18, 2015

Processing time: 298 Days and 9.9 Hours

AIM: To determine whether there is a functional difference between patients who actively follow-up in the office (OFU) and those who are non-compliant with office follow-up visits (NFU).

METHODS: We reviewed a consecutive group of 588 patients, who had undergone total joint arthroplasty (TJA), for compliance and functional outcomes at one to two years post-operatively. All patients were given verbal instructions by the primary surgeon to return at one year for routine follow-up visits. Patients that were compliant with the instructions at one year were placed in the OFU cohort, while those who were non-compliant were placed in the NFU cohort. Survey mailings and telephone interviews were utilized to obtain complete follow-up for the cohort. A χ2 test and an unpaired t test were used for comparison of baseline characteristics. Analysis of covariance was used to compare the mean clinical outcomes after controlling for confounding variables.

RESULTS: Complete follow-up data was collected on 554 of the 588 total patients (93%), with 75.5% of patients assigned to the OFU cohort and 24.5% assigned to the NFU cohort. We found significant differences between the cohorts with the OFU group having a higher mean age (P = 0.026) and a greater proportion of females (P = 0.041). No significant differences were found in either the SF12 or WOMAC scores at baseline or at 12 mo postoperative.

CONCLUSION: Patients who are compliant to routine follow-up visits at one to two years post-operation do not experience better patient reported outcomes than those that are non-compliant. Additionally, after TJA, older women are more likely to be compliant in following surgeon instructions with regard to follow-up office care.

Core tip: Following total joint arthroplasty, often patients are non-compliant with the surgeon requested follow-up protocol. This study aims to determine if there is a functional difference between patients who actively follow-up in office and those who are non-compliant with the visit protocol. Based on our results, patient compliance to routine follow-up visits at 12-24 mo post-operation does not lead to better patient-reported functional outcomes than those who are non-compliant. Additionally, older women are more likely to be compliant in adhering to surgeon post-operative follow-up instructions.

- Citation: Choi JK, Geller JA, Jr DAP, Wang W, Macaulay W. How are those “lost to follow-up” patients really doing? A compliance comparison in arthroplasty patients. World J Orthop 2015; 6(1): 150-155

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v6/i1/150.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v6.i1.150

Total hip arthroplasties (THA) and total knee arthroplasties (TKA) were initially designed to help relieve pain and improve function in people with debilitating joint pain. Outcomes from these surgeries are often determined through the use of patient reported, validated outcome tools[1-3]. Currently, total joint arthroplasty (TJA) has revolutionized the care of patients with end-stage arthritis of the hip and knee joint, by providing excellent long term results exceeding 20 years after surgery[4-6]. With future projections of close to 3.48 million TKAs and 572000 THAs occurring in the United States alone in the next 15 years, there is an increased importance on learning all criteria that make total joint replacement successful[7].

Following TJA, post-operative follow-up visits with the surgeon are the standard of practice in the United States; although, each surgeon often has his or her own protocol. In a survey of the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons membership, 80% of the respondents recommended that clinical and radiographic examinations following TJA should occur annually or biennially[8]. Regular follow-up visits, including radiographs, enable the surgeon to assess the result of a surgery and can rule out the possible need for revision, amongst other complications[9]. The delayed diagnosis of potential problems such as osteolysis, subsidence, component loosening, and infection can result in the need for a complex and costly revision surgeries[10,11], which often have less certain and worse outcomes than primary joint replacement[12].

As addressed, follow-up visits are also important for patient-reported outcomes based studies of TJA; however, despite recommendations from surgeons, not all patients that undergo TJA return to the office for routine examination. Since surgeons have been unable to estimate non follow-up patient outcomes, studies based on outcomes reported by patients who actively follow-up in the office may not be an accurate representation of TJA patients as a whole. Previous studies have reported that patients who are lost to follow-up are more likely to have worse outcomes and have had further surgical intervention at a second site than those patients who follow-up with their surgeon consistently[13,14]. Conversely, some other studies have shown varied and inconsistent results regarding lost to follow-up patients. Furthermore, most of these studies did not include complete pre-operative and post-operative outcomes for patients that followed-up in office (OFU) and those non-compliant with follow-up procedures (NFU)[15,16].

The purpose of this study was to determine whether there is a difference in functional outcomes between patients that follow-up annually in the surgeon’s office with those who are generally non-compliant with follow-up.

After receiving local institutional review board approval, we identified prospectively tracked patients who had received either a hip or a knee arthroplasty at our center. The patient cohort included primary and revision THA, primary and revision TKA, unicompartmental knee arthroplasties (UKA), bicompartmental knee arthroplasties (BCA), and metal-on-metal hip resurfacings (MOMHR). For those receiving staged, bilateral joint arthroplasties, only data collected from the first procedure were utilized. If a patient received a primary TJA and subsequently required a revision of another joint, he or she was excluded from the study to guarantee no duplication of patients. All procedures were performed by two fellowship trained, adult reconstruction orthopaedic surgeons.

From our CHKR registry, 588 patients, who were available for the annual follow-up visit, fit the inclusion criteria and were included into the study group. At the time of hospital discharge, all patients were given appointments at six weeks and three months post-operatively. Following the three month outpatient visit, each patient was given verbal instructions by his or her primary surgeon to return for another visit at one year post-operatively. At the one year visit, instructions were issued to return at two or three years post-operatively. When the patients checked out at each outpatient visit, each was given two possible options for future appointment scheduling: (1) immediately schedule the future appointment through the receptionist; or (2) contact the office by telephone at a later date to schedule the routine annual follow-up visit. For immediately scheduled appointments, the patient was given the date and time of the next appointment verbally and in written form. Patients with scheduled annual appointments were notified of their upcoming appointments through an automated calling system the day prior to the scheduled appointment.

Preoperative data collected included age, gender, comorbidities, body mass index (BMI), and preoperative diagnosis. Comorbidities collected for this report, verified through medical records, included: alcohol dependency, cancer, cardiac disease, endocrine disease (diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism), gastrointestinal disease, hematologic disease, hepatobiliary disease, hypertension, infectious disease, neurological disease, osteoporosis, Parkinson’s disease, documented psychiatric disorders, respiratory disease, smoking, steroid use, thromboembolic disease, and vascular disease. Also collected preoperatively and postoperatively were the Short Form 12 version 1 (SF12) and Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) patient questionnaires.

To determine postoperative follow-up compliance, we reviewed the electronic medical records of each patient who had undergone TJA. Patient cohorts were then divided into OFU and NFU based on compliance determination. Since patients are routinely compliant with the scheduled three month follow-up visit, these data were not analyzed in this study. Patients that returned to the outpatient office at one or two years post-operatively were included in the OFU cohort, with those not returning to the office included in the NFU group.

Between one and two years after TJA, follow-up questionnaires were collected via routine outpatient visits, mail, or telephone. All data collection, entry, and maintenance were performed using the Patient Analysis and Tracking System (PATS 4.0, Axis Clinical Software, Portland, OR). When the registry was initially reviewed at the start of the study, 206 patients did not have up to date follow-up information. These patients included those who had initially returned to the office, but were in-between biennial appointments. Patients with incomplete follow-up were then mailed the post-operative survey twice, with a minimum, four week interval between the two mailings. Remaining subjects were then contacted via telephone for interviews and/or sent more, repeated mailings until the remainder of the study group was eventually contacted.

To compare baseline characteristics among the groups, a χ2 test was used to analyze non-parametric variables, while an unpaired t test was used for the parametric variables. Analysis of covariance was used to compare the mean of clinical outcomes after arthroplasty between groups, controlling for age, gender, BMI, length of stay, pre-operative diagnosis, comorbidities, procedure, and preoperative SF12 and WOMAC scores. Statistical data analysis was conducted using SPSS Statistics v. 17.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, United States). P values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant.

Final analysis of the entire 588 patient cohort included: 172 TKAs, 200 THAs, 17 revision TKAs, 37 revision THAs, 22 UKAs, 14 BCAs, and 130 MOMHR patients. After initial database analysis, 75.5% of the total cohort had followed-up in the office, giving the OFU cohort 444 subjects and the NFU group 144 subjects. Of the 206 patients that were contacted to update their follow-up information, 62.1% of the patients (128 of 206) responded to the first or second mailing. From the remaining 78 non-responsive patients, 44 additional patients responded to further mailings and telephone interviews. Of the final 34 patients, one patient refused further participation and 33 were non-responsive to any form of contact. The breakdown of the lost patients included six that were initially in the OFU group and 28 in the NFU group.

Baseline characteristics according to each of the two groups are presented in Table 1. We found that there was a significant difference in both age (P = 0.026) and gender (P = 0.041) between the OFU and NFU groups. The mean age (62.5 years old) and percentage of females (56.8%) were both higher in the OFU group than the corresponding mean age (59.8 years old) and female percentage (47.2%) in the NFU cohort. Length of hospital stay, comorbidities, surgeon, operative side, procedure type, diagnosis, SF12 and WOMAC scores were not significantly different between the two cohorts. The types of procedures in each cohort are broken down in Table 2.

| Group | OFU | NFU | P value |

| Number of patients | 444 | 144 | |

| Surgeon 1 | 179 (40.3) | 51 (35.4) | 0.295 |

| Surgeon 2 | 265 (59.7) | 179 (64.6) | |

| Age at procedure | 62.4 ± 12.9 | 59.6 ± 13.3 | 0.026a |

| Length of stay (d) | 3.1 ± 1.3 | 3.4 ± 2.1 | 0.217 |

| Gender: female | 250 (56.3) | 67 (46.5) | 0.041a |

| Comorbidities | 324 (73.0) | 112 (77.8) | 0.252 |

| Operative side: right | 53.4% | 50% | 0.542 |

| SF12 physical | 30.4 ± 8.2 | 30.2 ± 7.2 | 0.778 |

| SF12 mental | 49.8 ± 11.4 | 47.9 ± 11.5 | 0.080 |

| WOMAC pain score | 44.9 ± 26.6 | 46.6 ± 27.8 | 0.506 |

| WOMAC stiffness score | 42.0 ± 25.1 | 43.3 ± 23.0 | 0.581 |

| WOMAC function score | 46.0 ± 21.6 | 48.2 ± 20.9 | 0.271 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30.3 ± 7.0 | 29.9 ± 6.9 | 0.634 |

| Diagnosis | 0.734 | ||

| Osteoarthritis | 347 (78.2) | 106 (73.6) | |

| Osteonecrosis | 45 (10.1) | 18 (12.5) | |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 44 (9.9) | 17 (11.8) | |

| Other | 8 (2.1) | 3 (1.8) | |

| Operative procedure | 0.541 |

| Groups | MOMHR | Primary BKA | Primary THA | Primary TKA | Primary UKA | Revision THA | Revision TKA | Total |

| OFU | 94 (21) | 12 (3) | 148 (34) | 130 (29) | 23 (5) | 28 (6) | 9 (2) | 444 (100) |

| NFU | 36 (25) | 2 (1) | 52 (36) | 31 (22) | 10 (7) | 9 (6) | 4 (3) | 144 (100) |

| Total | 130 | 14 | 200 | 161 | 33 | 37 | 13 | 588 |

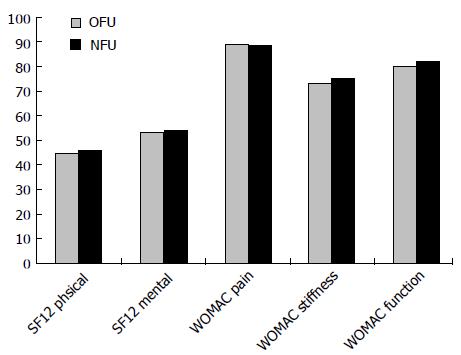

In evaluating the clinical, functional outcomes of the two groups, the mean follow-up periods for the OFU and NFU cohorts are 19.44 ± 8.4 and 20.28 ± 8.64 mo, respectively. While adjusting for confounding variables, there were no significant differences in either the postoperative SF12 mental and physical scores or in WOMAC pain, stiffness, and function scores. Raw scores can be found in Table 3 and seen graphically in Figure 1.

| Group | OFU | NFU | P value |

| SF12 physical | 45.1 ± 11.2 | 46.2 ± 11.2 | 0.685 |

| SF12 mental | 53.4 ± 9.2 | 54.1 ± 9.5 | 0.283 |

| WOMAC pain score | 89.1 ± 19.6 | 88.8 ± 20.5 | 0.612 |

| WOMAC stiffness score | 73.1 ± 24.7 | 75.3 ± 25.7 | 0.657 |

| WOMAC function score | 80.4 ± 21.7 | 82.4 ± 21.6 | 0.849 |

Post-operative follow-up visits have been an integral part of total joint arthroplasty practices. Several authors have suggested that even asymptomatic patients require follow-up care at least biennially following arthroplasty[8]. The reasoning behind this suggestion stems from the idea that even though some patients are asymptomatic, they may demonstrate radiographic or other signs of bone damage, which often require revision surgery despite the absence of symptoms[17]. While most cases of clinically significant osteolysis are typically identified at more than 6 years post-operatively, and with follow-up compliance expected to decrease over time, the detection of silent, clinical problems may be enhanced by early, regular, consistent follow-up visits. This strategy permits identification of potential complications at an earlier stage, and therefore, reduces the likelihood of complex revision procedures[18,19]. While some arthroplasty surgeons may conclude from presented data that routine follow-up visits are not necessary (or can be extended to every five years), anecdotally, at our urban, tertiary care center, we have found that when instructed to return every five years, patients are less likely to be compliant and do not return. From this information, we concur with Ries et al[20] that patients return every two to three years after the first annual follow-up visit.

Continual follow-up is also important for usage in post-operative outcome studies, as all such studies are limited by patient cooperation. If patients lost to follow-up have worse outcomes than those who continue to be assessed, as suggested by some authors, outcome studies, which do not account for these lost to follow-up patients, may give falsely optimistic results[13,14,21,22]. Therefore, extrapolations of the comparison between patients who did and did not consistently follow-up in office is essential to determining the real outcomes of an entire target population, particularly in long-term arthroplasty outcome studies.

Clohisy et al[23] showed that on the basis of a one-time verbal instruction, patient non-compliance with clinical follow-up after arthroplasty at one year post-operatively is up to 39%. Another study by Sethuraman et al[24] found that 45% of patients would prefer to not come into the office for routine evaluations at times greater than two years post TJA. This population based study, along with a separate study by de Pablo et al[25], showed that 15% of THA recipients self-reported receiving no post-operative follow-up radiographs, and only 42% of THA recipients had consistent follow-up over six years. The low office follow-up response rate observed in other studies corresponds well with our report. Our study showed that a large percentage (24.5%) of our patients did not visit the office for follow-up beyond their first year after arthroplasty. This low follow-up rate could be due to our simplistic follow-up protocol, which involves verbal instructions from the primary surgeon. If more intensive surgeon-directed instructions were given to patients, the rate of follow-up may possibly increase.

Many reasons are cited for the low rate of patient follow-up including: a change of residence, difficulty traveling, scheduling conflicts, doctor’s office delays, or simply the patient feels good[23,24]. In previous studies, older patients, patients with lower income, and patients with a lower education level were less likely to have consistent radiographic follow-up over six years post THA[25]. Additionally, these other studies demonstrated that younger patients and higher preoperative Harris hip gait scores were associated with follow-up compliance at two years post THA. Our study showed that the OFU and NFU groups had both different ages and gender proportions. Therefore, when comparing the mean clinical outcomes of the arthroplasties, we adjusted the age and gender through the use of analysis of covariance. One explanation for why younger men were less likely to be compliant with suggested follow-up is due to the desire to remain actively at work and not take the necessary time off to come into the office. This study was performed during a period of relative economic hardship in the surrounding area, which supports this speculation.

In a report by Dorey et al[15] on the influence of follow-up data loss on survivorship analysis in THA, they compared a cohort based on standard data collection with a 45% loss of follow-up to a cohort based on an almost complete data set with less than 10% loss of follow-up. The calculated survival rates for both groups were the same, leading Dorey et al[15] to conclude that the loss of follow-up data had little influence on analysis. Joshi et al[16] reviewed a series of 563 consecutive TKAs, and found no significant differences in revision rates or patient satisfaction between groups of patients who had or had not returned for follow-up office visits. An analysis by King et al[26] showed that there were no significant differences in Knee Society pain and function scores at a minimum of five years post-operative between follow-up and non-follow-up subjects. In contrast to these reports, Murray et al[14] published that patients lost to follow-up experienced worse outcomes in pain, range of motion, and radiologic features; however, these conclusions are based on the analysis of information derived from a patient’s last visit rather than from an actual, final follow-up visit. Similar to previous studies, our analysis shows that there are no significant differences in clinical outcomes, SF12 and WOMAC post-operative scores between the OFU and NFU cohorts.

One limitation of this study is investigator bias, which can occur during office visits or in telephone interviews[27-29]. McGrory et al[30] found that patient reported clinical scores following TKA were significantly different than those reported by physicians, although 97% of the responses were within one clinical grade of each other; however, no differences were noted in THA response. While investigator bias may have had a positive effect on the outcome of the OFU group, there were no significant differences in the patient reported, functional outcomes between the OFU and NFU cohorts. Another possible limitation is the inability to obtain a complete follow-up data set for our cohorts.

In conclusion, as observed in our two surgeon patient cohort from an academic, urban, tertiary care center, patients who do not visit the office for early route follow-up post TJA have similar outcomes to compliant patients, who routinely visit the office for follow-up. While we recommend to TJA patients to routinely follow-up in the office for both clinical and radiographical evaluations, our study shows that patients in our cohort were not negatively affected by non-compliance at early follow-up time periods of one to two years.

The authors of this article would like to acknowledge Jonathan Nyce and Kalman Katlowitz for their assistance on this project.

Total joint arthroplasty (TJA) has drastically changed the care of patients with end-stage arthritis of the hip and knee, and is only becoming more prevalent in today’s society, with more than 4 million TJAs expected to occur annually by 2030. Following TJA, adherence to post-operative follow-up visits allows surgeons to assess the results of a surgery, and to rule out possible needs for revision, amongst other complications. Delayed diagnoses of TJA complications often lead to less certain and worse outcomes. Currently, there is limited literature on the functional outcomes of those patients who adhere do not adhere to these follow-up protocols.

With the expected increase in the number of total joint arthroplasties performed, adherence to post-operative protocols will be key to limiting poor outcomes. Previous research regarding functional outcomes of TJAs often only takes into account those patients who adhere to follow-up protocol timelines; however, without taking into account the non-compliant patients, these outcomes may not be an accurate representation of TJA patients as a whole. The study of functional outcomes of the follow-up non-compliant patient is necessary to determine overall TJA outcomes.

In previous studies regarding the outcomes of total joints, there have been varying reports on how successful patients who have been lost to follow-up have been doing. Additionally, other studies only include patients who report to the office as scheduled, creating an unintentional bias, by not providing the true, overall picture of the success of the surgery. Authors’ study looks at the short-term, patient-reported functional outcome differences between those patients who were compliant to follow-up protocols to those that were non-compliant. Analysis of this data showed that in the short-term, non-compliant patients were not negatively affected with regard to functional outcomes.

This study shows that while it is important to have patients come back for routine, short-term follow-up to analyze for loose implants, infection, and heterotopic ossification, amongst other complications, there is no patient-reported functional outcome difference between compliant and non-compliant patients.

Compliance - adherence of patients to the follow-up visit timeline as requested by the operating surgeon.

This paper shows a well written research study on an important problem in monitoring total joint outcomes. The study highlights the facts that non-compliant patients are generally functioning at the same level as compliant patients, and that there may be future needs to monitor patient outcomes electronically in a way such that an office visit does not have to occur.

P- Reviewer: Fisher DA, Malik MHA, Mugnai R S- Editor: Wen LL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Bourne RB, McCalden RW, MacDonald SJ, Mokete L, Guerin J. Influence of patient factors on TKA outcomes at 5 to 11 years followup. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;464:27-31. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Chesworth BM, Mahomed NN, Bourne RB, Davis AM. Willingness to go through surgery again validated the WOMAC clinically important difference from THR/TKR surgery. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:907-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ethgen O, Bruyère O, Richy F, Dardennes C, Reginster JY. Health-related quality of life in total hip and total knee arthroplasty. A qualitative and systematic review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A:963-974. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Brown SR, Davies WA, DeHeer DH, Swanson AB. Long-term survival of McKee-Farrar total hip prostheses. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;157-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Callaghan JJ, Albright JC, Goetz DD, Olejniczak JP, Johnston RC. Charnley total hip arthroplasty with cement. Minimum twenty-five-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:487-497. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Hamadouche M, Boutin P, Daussange J, Bolander ME, Sedel L. Alumina-on-alumina total hip arthroplasty: a minimum 18.5-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A:69-77. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:780-785. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2079] [Cited by in RCA: 3260] [Article Influence: 181.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Teeny SM, York SC, Mesko JW, Rea RE. Long-term follow-up care recommendations after total hip and knee arthroplasty: results of the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons’ member survey. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18:954-962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mehin R, Yuan X, Haydon C, Rorabeck CH, Bourne RB, McCalden RW, MacDonald SJ. Retroacetabular osteolysis: when to operate? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;247-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bhatia M, Obadare Z. An audit of the out-patient follow-up of hip and knee replacements. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2003;85:32-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lonner JH, Siliski JM, Scott RD. Prodromes of failure in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1999;14:488-492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mahomed NN, Barrett JA, Katz JN, Phillips CB, Losina E, Lew RA, Guadagnoli E, Harris WH, Poss R, Baron JA. Rates and outcomes of primary and revision total hip replacement in the United States medicare population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A:27-32. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Laupacis A. The validity of survivorship analysis in total joint arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71:1111-1112. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Murray DW, Carr AJ, Bulstrode C. Survival analysis of joint replacements. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75:697-704. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Dorey F, Amstutz HC. The validity of survivorship analysis in total joint arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71:544-548. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Joshi AB, Gill GS, Smith PL. Outcome in patients lost to follow-up. J Arthroplasty. 2003;18:149-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hozack WJ, Mesa JJ, Carey C, Rothman RH. Relationship between polyethylene wear, pelvic osteolysis, and clinical symptomatology in patients with cementless acetabular components. A framework for decision making. J Arthroplasty. 1996;11:769-772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lavernia CJ. Cost-effectiveness of early surgical intervention in silent osteolysis. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13:277-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Orishimo KF, Claus AM, Sychterz CJ, Engh CA. Relationship between polyethylene wear and osteolysis in hips with a second-generation porous-coated cementless cup after seven years of follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A:1095-1099. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Ries MD, Link TM. Monitoring and risk of progression of osteolysis after total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:2097-2105. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Norquist BM, Goldberg BA, Matsen FA. Challenges in evaluating patients lost to follow-up in clinical studies of rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:838-842. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Wildner M. Lost to follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77:657. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Clohisy JC, Kamath GV, Byrd GD, Steger-May K, Wright RW. Patient compliance with clinical follow-up after total joint arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:1848-1854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Sethuraman V, McGuigan J, Hozack WJ, Sharkey PF, Rothman RH. Routine follow-up office visits after total joint replacement: do asymptomatic patients wish to comply? J Arthroplasty. 2000;15:183-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | de Pablo P, Losina E, Mahomed N, Wright J, Fossel AH, Barrett JA, Katz JN. Extent of followup care after elective total hip replacement. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:1159-1166. [PubMed] |

| 26. | King PJ, Malin AS, Scott RD, Thornhill TS. The fate of patients not returning for follow-up five years after total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A:897-901. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Fowler FJ, Gallagher PM, Stringfellow VL, Zaslavsky AM, Thompson JW, Cleary PD. Using telephone interviews to reduce nonresponse bias to mail surveys of health plan members. Med Care. 2002;40:190-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | McHorney CA, Kosinski M, Ware JE. Comparisons of the costs and quality of norms for the SF-36 health survey collected by mail versus telephone interview: results from a national survey. Med Care. 1994;32:551-567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 400] [Cited by in RCA: 398] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Robertsson O, Dunbar MJ. Patient satisfaction compared with general health and disease-specific questionnaires in knee arthroplasty patients. J Arthroplasty. 2001;16:476-482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | McGrory BJ, Morrey BF, Rand JA, Ilstrup DM. Correlation of patient questionnaire responses and physician history in grading clinical outcome following hip and knee arthroplasty. A prospective study of 201 joint arthroplasties. J Arthroplasty. 1996;11:47-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |