Revised: April 1, 2012

Accepted: May 13, 2012

Published online: May 18, 2012

Scurvy is caused by prolonged severe dietary deficiency of ascorbic acid, in which the breakdown of intercellular cement substances leads to capillary hemorrhages and defective growth of fibroblasts, osteoblasts and odontoblasts, resulting in impaired synthesis of collagen, osteoid and dentine. It is characterized by hemorrhagic gingivitis, subperiosteal hemorrhages, perifollicular hemorrhages, and frequently petechial hemorrhages (especially on the feet). People with abnormal dietary habits, mental illness or physical disability are prone to develop this disease. Epiphyseal separation is known to occur in scurvy but is rarely seen now. Epiphyseal separation from the metaphysis is always through the zone of calcified cartilage, known as “scorbutic lattice”, which in the radiographs is represented as “the white line of Frenkel”. We report a case of multiple epiphyseal separations in a cerebral palsy child because of vitamin C deficiency. The child was treated with splintage of extremity and nutritional supplementation. All physeal separation healed completely without any deformity.

- Citation: Gupta S, Kanojia R, Jaiman A, Sabat D. Scurvy: An unusual presentation of cerebral palsy. World J Orthop 2012; 3(5): 58-61

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v3/i5/58.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v3.i5.58

Epiphyseal separations are known to occur in scurvy, but only a few such cases have been reported in children with cerebral palsy[1,2]. Even rarer is epiphyseal separation involving three or more epiphysis in a single patient. We report a case of epiphyseal separation of the bilateral proximal humerii and bilateral distal end of femur in a scurvy affected quadriplegic cerebral palsy child. The aim of this article is to underline the rarity and gravity of this disease and its possible more frequent appearance in children affected by cerebral palsy.

A 6 year old female child presented with a 15 d history of non traumatic sudden onset swelling of bilateral shoulders and bilateral knees. The child was a known case of spastic quadriplegic cerebral palsy with seizure disorder.

Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) score of child was level V. She was completely non ambulatory and had been on oral phenytoin for the last four years; however, the onset of swelling was not related to an epileptic attack.

The child was lethargic but irritable and mildly febrile, was 91 cm in length and 11.5 kg in weight. Oral ulcers were evident. Bilateral upper limbs and lower limbs were spastic with poor power in all the extremities. Bilateral shoulders and knees were grossly swollen with overlying shiny skin (Figure 1).

On gentle palpation of the joints, the temperature was not raised and muffled crepitus was palpable in the affected joints. Any attempted movement of the affected joints was painful and restricted. There was no regional lymphadenopathy and the other joints were normal.

Laboratory parameters revealed severe anemia (hemoglobin 4.4 g/dL) and normal serum calcium, phosphorus and alkaline phosphatase levels (Table 1).

| Blood/serum | Patient’s value | Normal value |

| Hemoglobin | 4.4 gm/dL | 14.3-18.3 gm/dL |

| Total leucocytes count | 7200 | 5.5-15.5 × 103 cells/µL |

| Differential count | Neutrophils 52.4% | 54%-62% |

| Lymphocytes 36.2% | 25%-33% | |

| Mean corpuscular volume | 54.9 | 79.1-98.9 fL |

| Platelets | 382 000 | 150-400 × 103 cells/µL |

| International normalised ratio | 1.2 | 0.9-2.0 |

| Serum calcium | 9.8 | 8.4-10.8 mg/dL |

| Serum phosphorous | 4.4 | 3.7-5.6 mg/dL |

| Serum alkaline phosphatase | 197 | 145-420 IU/L |

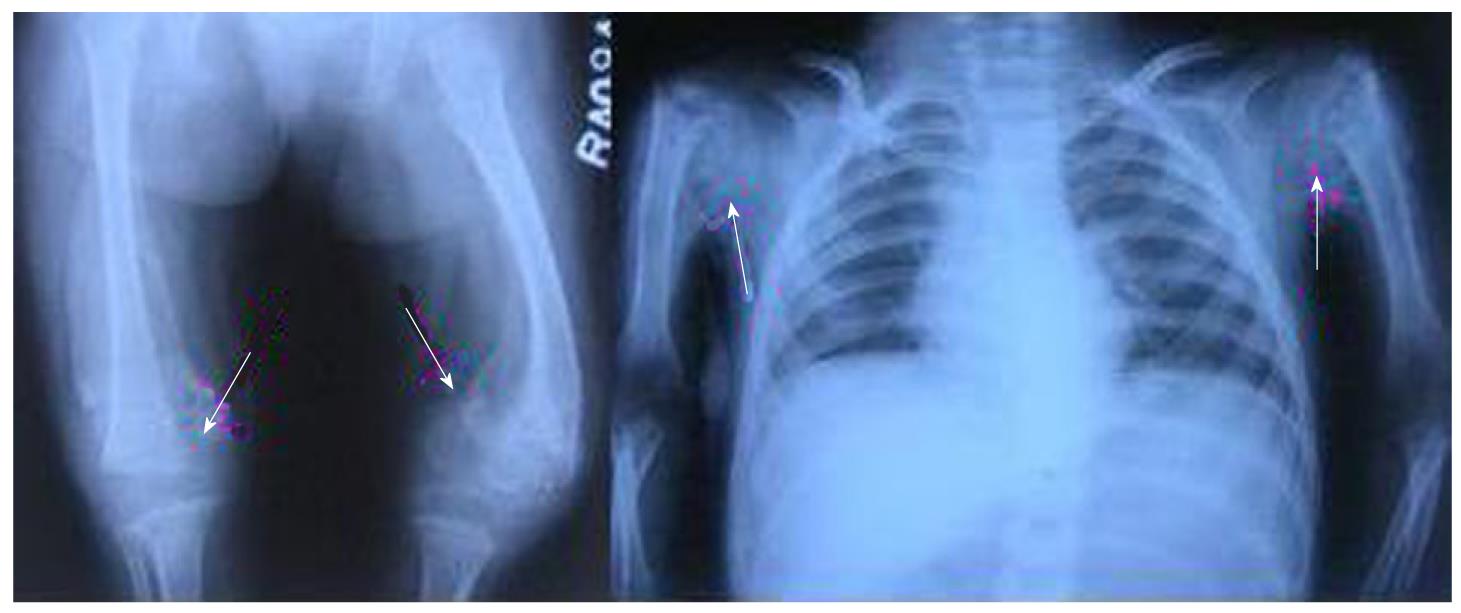

Radiographs of bilateral shoulder and knee joints revealed complete separation of the proximal humerus epiphysis on the right side and the distal femoral epiphysis on the left side and partial separation of the left proximal humeral epiphysis and right distal femoral epiphysis (Figure 2).

Early subperiosteal hematoma was visible on all affected areas. Radiographs showed evidence of osteoporosis and thinning of cortices along with a distinctive radiological sign of scurvy, “Frenkel’s white line”.

The inability to reach a workable diagnosis prompted us to further enquire from the caregivers and it was revealed that the child was surviving on biscuits and pasteurized milk solely.

On the basis of clinical and radiological features, the child was diagnosed as a case of scurvy, confirmed after serum vitamin C level estimation, which was < 0.12 mg/dL (normal range 0.20-1.90 mg/dL).

The child was splinted with high groin plaster slabs in both the lower limbs and cuff and collar slings in both the upper limbs after gentle attempt of closed reduction. Vitamin C 200 mg per day along with hematinics was started. After 5 wk, as the pain and swelling subsided, plaster was removed and passive range of motion was started. All the slips healed within 4 mo. Even the completely displaced slips remodeled very well. At 6 mo of follow-up, all the slips were completely remodeled without obvious deformity (Figure 3).

The underlying basic biochemical defect in scurvy is failure to hydroxylate proline and lysine, an essential step in collagen formation (which is dependent on ascorbate).

Scurvy is rarely seen now because of the improvement in the nutritional and socioeconomic status of most populations. Children suffering from severe cerebral palsy are at increased risk for development of metabolic bone disease[3,4]. Various factors, including poor intake, oral motor dysfunction, feeding problems, nonambulatory status and use of antiepileptics, contribute to deficiency of essential vitamins and minerals in this group of children.

Children with scurvy are irritable and lethargic, may have gum bleeding, petechiae, eccymosis, loosening of teeth, bone pains, weakness and poor wound healing. Early diagnosis requires a high degree suspicion as delay can result in jaundice, generalized edema, oliguria, neuropathy, fever, convulsions and eventually death may be seen. There are certain diseases that can mimic scurvy. Details of these diseases are given in Table 2.

| Differential diagnosis |

| Child abuse and neglect |

| Medication side effects |

| Autoimmune diseases (e.g., henoch-schönlein purpura, systemic lupus erythematosus, sjogren syndrome) |

| Vitamin D deficiency and related disorders |

| Clotting factor deficiencies |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation |

| Platelet dysfunction (e.g., immune thrombocytopenic purpura) |

| Senile purpura |

| Thrombophlebitis, deep venous thrombosis |

| Meningococcemia, rocky mountain spotted fever |

| Hematological malignancies (e.g., acute lymphoblastic leukemia) |

| Hypersensitivity vasculitis (leukocytoclastic vasculitis) |

| Necrotizing gingivitis |

| Osteomyelitis |

| Pediatric syphilis |

| Septic arthritis |

Radiographic features include diminished bone density and cortical thinning. In addition, a white line of radiodensity is seen on the metaphyseal side of the physis, known as the white line of Frenkel[5]. This white line is due to an increase in the width and opacity of the zone of provisional calcification at the end of the metaphysis. Adjacent to this radiodense line is a radiolucent line which results in a very white appearance to this line.

Partial and complete separation of the epiphysis and fractures of calcified cartilage of the epiphyseal plate are known to occur in scurvy[6,7]. The usual locations of these epiphyseal injuries are the lower femur, upper humerus, osteochondral junction and lower tibia[5]. It is very rare to see epiphyseal separation involving three or more epiphyses. Aroojis et al[2] presented a series of four patients of cerebral palsy who had epiphyseal separation because of scurvy. In their series, diagnosis was based upon clinical and radiological features. Out of these four patients, only one patient had epiphyseal separation of both proximal humerii and both distal femurs. In our patient, there was separation of epiphyses of both proximal humerii and both distal femurs. The diagnosis was based upon clinical radiological features and was confirmed by assessment of vitamin C level.

Separation of the epiphysis from the metaphysis is always through the zone of calcified cartilage, known as “scorbutic lattice”, which in the radiographs is represented as “the white line of Frenkel”[5]. A lattice fracture occurs in the zone of provisional calcification; because of this fracture, subperiosteal hemorrhages occur that leads to stripping of the periosteum from the shaft (particularly from the periphery of the epiphyseal plate)[5]. The epiphysis along with growth plate remains lined up to the denuded shaft with a periosteal sleeve containing a hematoma. Upon nutritional supplementation and administration of vitamin C, this subperiosteal hematoma begins to calcify. New bone is laid down on the side of the shaft where the epiphysis is displaced (and to a lesser degree on the opposite side). Thus, a new shaft is formed within the periosteal sleeve, while the protruding shaft undergoes rapid resorption. After subperiosteal bone formation, the epiphysis becomes centered on the widened metaphysic and remains in that position until the phase of remodeling[6-8].

So it can be inferred that separation of the epiphysis in scurvy is best treated conservatively by splintage and observation and a closed or open reduction of the displaced epiphysis is rarely required. Complete remodeling is the rule and residual deformity or disturbance in longitudinal bone growth is seldom seen.

The rarity of residual deformity in such epiphyseal separation can be explained by the blood supply to the growth plate. Trueta and associates have shown that the vessels on the epiphyseal side of the growth plate supply nourishment for resting and proliferative cartilage cells, which are primarily responsible for longitudinal growth of bone. In scurvy, epiphyseal separation occurs in the zone of provisional calcification so the blood vessels present on the epiphyseal side of growth plate are not damaged[7].

Deficiency of vitamin C is a common cause of epiphyseal separation in severely malnourished children and children with cerebral palsy appear to be more prone to this disease. Vitamin C supplementation along with immobilization for few weeks until the pain and swelling has subsided is sufficient for its management. Closed or open reduction is usually not required. Even in severe slips, healing with excellent remodeling is seen.

Peer reviewers: Federico Canavese, MD, PhD, Centre Hospitalier Univesitaire Estaing, Service de Chirurgie Infantile, 1, place Lucie Aubrac, 63003 Clermont Ferrand, France; Saidur Rahman Mashreky, MBBS, MPH, PhD, Public Health and Injury Prevention, Centre for Injury Prevention and Research Bangladesh, House B-162, Road 23, New Dohs, Mohakhali, Dhaka 1206, Bangladesh

S- Editor Yang XC L- Editor Roemmele A E- Editor Yang XC

| 1. | Nerubay J, Pilderwasser D. Spontaneous bilateral distal femoral physiolysis due to scurvy. Acta Orthop Scand. 1984;55:18-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Aroojis AJ, Gajjar SM, Johari AN. Epiphyseal separations in spastic cerebral palsy. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2007;16:170-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Henderson RC, Lin PP, Greene WB. Bone-mineral density in children and adolescents who have spastic cerebral palsy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:1671-1681. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Shaw NJ, White CP, Fraser WD, Rosenbloom L. Osteopenia in cerebral palsy. Arch Dis Child. 1994;71:235-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Scott W. Epiphyseal dislocations in scurvy. J Bone Joint Surg. 1941;23:314–322. |

| 6. | Caffey J. Paediatric Xray diagnosis. 7th ed. Chicago: Yearbook Publishers; 1978; 1459–1466. |

| 7. | Silverman FN. Recovery from epiphyseal invagination: sequel to an unusual complication of scurvy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1970;52:384-390. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Aroojis A, D'Souza H, Yagnik MG. Separation of the proximal humeral epiphysis. Postgrad Med J. 1998;74:752-755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |