Published online Feb 18, 2020. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v11.i2.76

Peer-review started: March 28, 2019

First decision: July 30, 2019

Revised: December 3, 2019

Accepted: December 5, 2019

Article in press: December 5, 2019

Published online: February 18, 2020

Processing time: 328 Days and 10.6 Hours

On September 20, 2017 Hurricane Maria, a category 4 hurricane, made landfall on the eastern coast of Puerto Rico. This was preceded by Hurricane Irma, a category 5 hurricane, which passed just off the coast 13 d prior. The destruction from both Hurricane Irma and Maria precipitated a coordinated federal response which included the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the United States military. The United States Army dispatched the 14th Combat Support Hospital (CSH) to Humacao, a city on the eastern side of the island where Maria made landfall. The mission of the 14th CSH was to provide medical humanitarian aid and conduct disaster relief operations in support of the government of Puerto Rico and FEMA. During the 14th CSH deployment to Puerto Rico, 1157 patients were evaluated and treated. Fifty-seven operative cases were performed to include 23 orthopaedic cases. The mean age of the orthopaedic patients treated was 45.7 years (range 13-76 years). The most common operation was irrigation and debridement of open contaminated and/or infected wounds. Patients presented a mean 10.8 d from their initial injury (range 1-40 d). Fractures and infections were the most common diagnoses with the greatest delay in treatment from the initial date of injury. The deployment of the 14th CSH to Puerto Rico was unique in its use of air transport, language and local customs encountered, as well as deployment to a location outside the continental United States. These factors coupled with the need for rapid deployment of the 14th CSH provided valuable experience which will undoubtedly enable future success in similar endeavors.

Core tip: Health care providers embarking on humanitarian and disaster relief efforts should consider the following factors: What specific diagnoses or injuries can your team safely manage considering the knowledge, technical ability, equipment, and facilitates your team possesses? What was the health of the patient population pre-disaster and their access to quality health care? What can be done to help mitigate language and cultural barriers which make effective communication with patients difficult? What local providers and resources can be engaged to ensure continued care for patients after relief efforts have concluded?

- Citation: Lanham N, Bockelman K, Lopez F, Serra MM, Scanlan B. Orthopaedic care provided by the 14th combat support hospital in support of humanitarian and disaster relief after hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico. World J Orthop 2020; 11(2): 76-81

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v11/i2/76.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v11.i2.76

On September 20, 2017 Hurricane Maria, a category 4 hurricane, made landfall on the eastern coast of Puerto Rico. This was preceded by Hurricane Irma, a category 5 hurricane, which passed just off the coast 13 d prior. The destruction which ensued precipitated a coordinated federal response which included the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and the United States military. United States Army assets were mobilized to Puerto Rico to provide support in the form of personnel, food, drinking water, medicine, and military aircraft. In addition to providing immediate relief services, the United States Army dispatched the 14th Combat Support Hospital (CSH) to Humacao, a city on the eastern side of the island where Maria made landfall. The mission of the 14th CSH was to provide medical humanitarian aid and conduct disaster relief operations in support of the government of Puerto Rico and FEMA.

From October 6 through November 12, 2017, the 14th CSH provided medical and surgical services for the population of Humacao and surrounding region. The purpose of this paper is to describe the mission and capability of the 14th CSH, detail the operative care provided to orthopaedic patients, and provide lessons learned from the humanitarian and disaster relief operations conducted in Puerto Rico in response to Hurricane Maria.

The 14th CSH is one of several active duty combat support hospitals within the Army Medical Department. CSH’s are an essential element within the echelons of care in battlefield medicine. A CSH affords the highest level of medical, surgical, and trauma care available within the combat zone. They possess modular configurations which allow commanders to tailor medical support to various operational environments. Specialists which can be assigned to a CSH include general surgeons, orthopaedic surgeons, thoracic surgeons, vascular surgeons, obstetrician/gynecologists, and urologic surgeons. In addition to laboratory and radiographic capabilities, CSH’s also offer a blood blank and nutrition capabilities. The 44-bed CSH configuration can have up to 250 personnel, with two operating tables, 20 intensive care unit (ICU) beds, and 24 holding beds. Within combat environments, patients are typically held no longer than 72 h prior to evacuation to higher echelons of care[1].

While the primary mission of the 14th CSH is to provide the highest level of patient care within combat zones in support of conventional military operations, a secondary mission of the 14th CSH involves the Defense Support of Civil Authorities (DSCA). DSCA includes support provided by United States military forces, Department of Defense (DOD) civilians, DOD contract personnel, DOD Component assets, and National Guard forces in response to requests from civil authorities for domestic emergencies within the continental United States, Alaska, Hawaii and United States territories. This support can involve law enforcement, certain domestic activities, or certain qualifying entities for special events[2]. Examples of prior United States military DSCA missions include: The response to Hurricane Katrina[3] in 2005 as well as hurricane Sandy[4] in 2012.

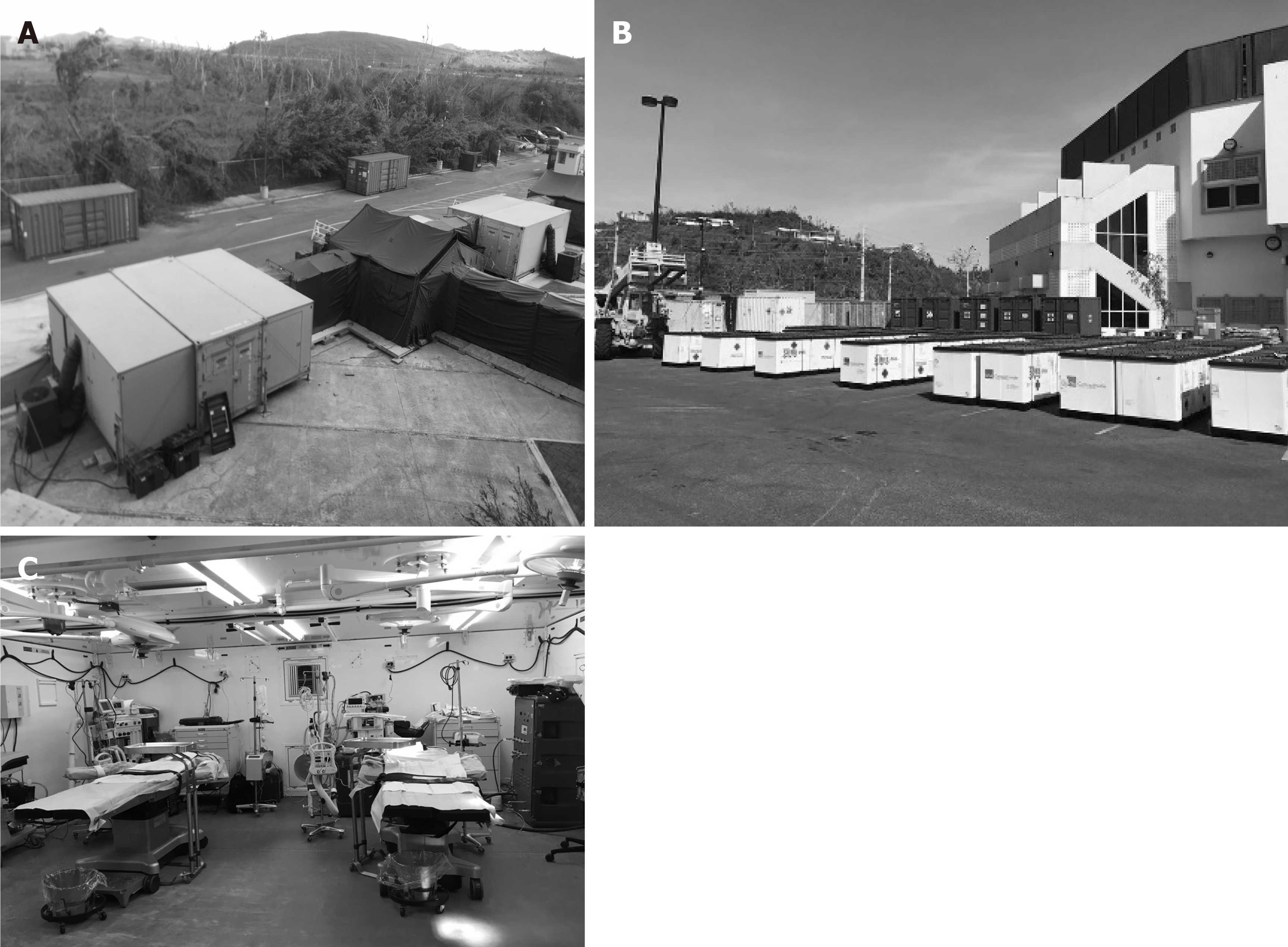

Given the scope and scale of destruction which resulted from Hurricane Maria, the 14th CSH was activated in support of its DCSA mission role. The operations of the 14th CSH were conducted out of the Humacao Arena, an 8000-seat building which was the home of a local professional basketball team. The structure suffered minimal damage and possessed its own generator with central air conditioning. It was also located within a few miles of the city’s two main hospitals and was easily accessible by two major highways. A landing zone was set up immediately across from the arena in a large open field for air medical and transport operations. The 14th CSH operating room and radiology facilities were set up just outside the arena (Figure 1). The Emergency Medical Treatment section, Pharmacy, Laboratory, as well as inpatient wards were set up within the arena (Figure 2).

Patients presented to the CSH either by military or local civilian medical transport. The patients were then evaluated by triage nurses and physicians to ensure the patients could be effectively managed with the resources of the CSH. Patients necessitating resources beyond the capability of the CSH were transferred to other military or local medical facilities.

During the 14th CSH deployment to Puerto Rico, 1157 patients were evaluated and treated. Fifty-seven operative cases were performed to include 23 orthopaedic cases. The mean age of the orthopaedic patients treated was 45.7 years (range 13-76 years). The most common operation was irrigation and debridement of open contaminated and/or infected wounds (Table 1). Patients presented a mean 10.8 d from their initial injury (range 1-40 d). Fractures and infections were the most common diagnoses with the greatest delay in treatment from the initial date of injury (Table 1).

| Sex | Age (yr) | Diagnosis | ASA | Time from injury (d) | Operative treatment |

| M | 56 | Foreign body | 3 | 3 | Foreign body excision/I&D |

| F | 26 | Complex elbow dislocation | 1 | 1 | CR splinting |

| M | 13 | BBFF | 1 | 1 | CR splinting |

| M | 42 | BBFF | 3 | 40 | ORIF |

| F | 25 | Humerus fx | 2 | 2 | CR splinting |

| M | 14 | Radial shaft fx | 1 | 1 | ORIF |

| F | 71 | Patella fx | 2 | 1 | ORIF |

| M | 76 | Flexortenosynovitis | 3 | 35 | Amputation |

| F | 41 | Trimal ankle fx | 2 | 40 | CR splinting |

| M | 66 | Crush injury digit | 1 | 2 | CRPP, nailbed repair |

| M | 52 | Open 5th MC fx1 | 4 | 1 | I&D, 5th ray resection |

| M | 47 | Pre-patella septic bursitis/septic knee2 | 3 | 28 | I&D |

| M | 26 | DRF with acute CTS | 2 | 2 | ORIF, CTR |

| F | 68 | Bimal ankle fx | 4 | 1 | ORIF |

| M | 63 | Patella fx | 1 | 4 | ORIF |

| M | 36 | Crush injury digit | 2 | 1 | Nailbed repair |

| M | 27 | Ulna shaft fx | 1 | 2 | ORIF |

| M | 51 | Distal biceps rupture | 2 | 24 | Open repair |

| 45.73 | 2.33 | 10.83 |

Patients were assessed pre-operatively by the Medicine and Anesthesia services. Mean the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) scores were 2.3 (Table 1). Diabetes was the most common co-morbid diagnosis. Regional anesthesia was performed at the discretion of the Anesthesia Service after discussion with the operating physician. A total of 8 regional blocks were performed. All patients received pre-operative antibiotics. Intra-operative cultures, when obtained, were sent to a local hospital laboratory for processing. Intra-operative plain radiographs were performed with a portable unit which had a viewing station located just outside the operating room.

Five patients were discharged on the same day as their operation. Patients without risk factors for DVT and isolated lower extremity fractures were managed with 81 mg ASA twice daily for DVT prophylaxis as inpatients. One post-operative patient was transferred to another facility after his septic joint was irrigated and debrided for further evaluation and treatment given his multiple medical co-morbidities which necessitated a higher level of medical care. The remaining post-operative patients were discharged to their respective local residences with patient instructions, follow-up plans of care, medications, and dressing supplies if necessary.

Resorbable suture was used when 2 wk follow up went beyond the anticipated conclusion of CSH operations. In addition, patient follow-up and care coordination was made with local providers and other military medical assets. These included a local non-operative orthopaedist, the ambulatory clinic at Fort Buchanan, and the USNS Comfort. No immediate complications were observed however even immediate short term follow-up was limited. Mean follow-up with post-operative patients was 7.5 d (range 0-28 d).

This case series provides the first description of orthopaedic care provided by a CSH on a DSCA mission. The deployment of the 14th CSH to Puerto Rico was unique for many reasons. These included: Use of air transport, language and local customs encountered, as well as deployment to a location outside the continental United States. These factors coupled with the need for rapid deployment of the 14th CSH provided valuable experience which will undoubtedly enable future success in similar endeavors.

Another unique element of the 14th CSH relief efforts was its direct collaboration with Disaster Medical Assistance Teams (DMAT). A DMAT is a trained, mobile, self-contained, self-sufficient, multidisciplinary medical team that can respond rapidly after a disaster (48 to 72 h) to provide medical treatment to an affected area. The team can include physicians, nurses, pharmacists, paramedics, and EMTs. DMATs fall under the National Disaster Medical System (NDMS), a federally coordinated system with the United States Department of Health and Human Services[5]. Multiple DMATs assisted the 14th CSH efforts for 2 weeks at a time and were an important part of the triage and treatment of the local population. These teams operated out of the same location and used the same facilities as the 14th CSH.

Shortly after the 14th CSH became operational, representatives from the 14th CSH contacted local hospitals to assist with helping these facilities become more operational. This included coordinating the request and delivery of needed supplies such as tarps and generator equipment. In addition, the 14th CSH engaged local and regional government to help with delivery of food and water to local organizations and churches for distribution.

Within the Humacao area, the 14th CSH was able to locate only one practicing orthopaedic surgeon who was working part-time as a non-operative provider. This led to challenges with coordinating care for patients in anticipation of the 14th CSH’s departure. In addition, patients faced challenges with access to orthopaedic surgeons outside of the Humacao area due to overburdened hospitals as well as underinsurance and/or no insurance. This left a large patient population within the Humacao region in need of orthopaedic services. Many of the patients presenting for orthopaedic care had delayed presentations which made treatment more difficult. This included patients presenting with malunited fractures and sub-acute infections. Other challenges included adverse effects of weather on facilities and equipment which included power outages, loss of climate control in the operating room and patient wards, and water leakage into the operating room and equipment/supply areas. The operating room did not possess a viewing station for digitally captured radiographs which made viewing intra-operative radiographs challenging.

Similar challenges have been described by other authors in disaster relief efforts. Sechriest et al[6] characterized the orthopaedic care provided on the USNS Mercy after the 2004 Asian Tsunami as “challenging at every level”. This involved patient deconditioning and/or poor physical health, chronic and complex injuries and conditions, and lack of timely follow-up by physicians with orthopaedic expertise in the post-disaster region. In addition, the authors describe communication with patients and their families as perhaps the single greatest challenge faced by the providers. Despite interpreters from the host nation, language and cultural barriers presented difficulties in gathering accurate histories, obtaining informed consent, and communicating post-operative expectations and plans for continued care. Beitler et al[7] cited one of the greatest challenges for the 48th CSH, during Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan, was maintaining the balance between capabilities and requirements. In providing care to Afghan and United States contractors, the pediatric and more elderly patients which were treated frequently required advanced ICU care followed by rehabilitation. Patients evacuated to the 48th CSH because of limited local medical infrastructure led to significant challenges with respect to discharge planning, transport, and placement. Born et al[8] describe lack of systems interface as a recurrent problem in disaster response and note that during the 2005 Hurricane Katrina relief effort, no communication existed between government and/or military responders for several days. Due to flooding and power outages, medical facilities were isolated, which allowed for little command and control as well as limited contact with the relief efforts surrounding them. The authors also describe challenges faced by the USNS Comfort during the 2010 Haiti Earthquake which included access to a single C-arm as well as a limited supply of orthopaedic implants.

Despite experiencing many similar challenges, the 14th CSH was able to provide orthopaedic care to residents within the Humacao region and performed nearly two dozen orthopaedic cases. Although follow-up was very limited, there were no immediate complications. In all cases, management was guided by the principle of “primum non nocere” (first do no harm). Additional objectives focused on operative intervention which required limited ancillary support and follow-up. Comprehensive work-up and treatment was performed by a multi-disciplinary team comprised of specialists in nutrition, pharmacy, medicine, anesthesia, and surgery in order to optimize patients peri-operatively.

As an essential element within the echelons of care in battlefield medicine with equipment and personnel typically configured for combat zones, the 14th CSH primarily possessed capability for damage control intervention with less capacity for the subacute and ambulatory patients which presented during the relief effort. When fixation was performed it was most often definitive fixation with small fragment or mini-fragment plates and screws. Percutaneous K-wire fixation was also utilized in a few cases in the hand and upper extremity. One case necessitated the shipment of implants to the CSH. In addition, capability for definitive management for subacute and ambulatory patients was also limited due to a lack of fluoroscopy and a radiolucent operating table.

This case series illustrates the unique capabilities of the CSH and as well as the orthopaedic conditions encountered the hurricane Maria disaster relief effort. It also highlighted challenges of providing care to patients with limited resources and uncertain follow-up care. Future similar efforts will undoubtedly benefit from the experience gained and lessons learned by the 14th CSH’s deployment to Puerto Rico.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ju SQ, Mogulkoc R S-Editor: Wang J L-Editor: A E-Editor: Liu MY

| 1. | Bagg MR, Covey DC, Powell ET 4th. Levels of medical care in the global war on terrorism. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2006;14:S7-S9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Defense Support of Civil Authorities. Department of Defense Directive Number 3025.18. December 29, 2010. |

| 3. | Winslow DL. Wind, rain, flooding, and fear: coordinating military public health in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41:1759-1763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | USNORTHCOM Hurricane Sandy Response Support. [published on November 1, 2012]. Available from: http://www.northcom.mil/Newsroom/Article/563652/usnorthcom-hurricane-sandy-response-support-nov-1/. |

| 5. | Arziman I. Field Organization and Disaster Medical Assistance Teams. Turk J Emerg Med. 2015;15:11-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sechriest VF 2nd, Lhowe DW. Orthopaedic care aboard the USNS Mercy during Operation Unified Assistance after the 2004 Asian tsunami. A case series. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:849-861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Beitler AL, Wortmann GW, Hofmann LJ, Goff JM. Operation Enduring Freedom: the 48th Combat Support Hospital in Afghanistan. Mil Med. 2006;171:189-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Born CT, Cullison TR, Dean JA, Hayda RA, McSwain N, Riddles LM, Shimkus AJ. Partnered disaster preparedness: lessons learned from international events. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2011;19 Suppl 1:S44-S48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |