Published online Sep 18, 2019. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v10.i9.339

Peer-review started: March 8, 2019

First decision: April 16, 2019

Revised: May 15, 2019

Accepted: August 12, 2019

Article in press: August 13, 2019

Published online: September 18, 2019

Processing time: 208 Days and 8 Hours

Heel pain is a common orthopaedic complaint, and if left untreated can be a source of chronic morbidity. Accurate diagnosis can be challenging, owing to the complex anatomy and multiple pain generators present in the foot. We aim to share our clinical experience managing an unusual case of chronic heel pain secondary to osteochondroma.

A 41-year-old obese male who works as a porter presented with a long-standing history of left plantar heel pain. He was assessed to have point tenderness over the plantar insertion of the calcaneus as well as a positive Silfverskiöld test. He was treated for plantar fasciitis and tight gastrocnemius but failed conservative therapies as well as surgical intervention. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed the presence of a pedunculated bony protrusion over the plantar aspect of the calcaneus. The decision was made for excision of the osteochondroma, and the patient has been pain-free since.

Osteochondromas are rarely symptomatic in skeletally mature patients. While most are benign with a very low risk of malignant transformation, surgical excision can yield excellent results and significant pain relief in symptomatic patients.

Core tip: Heel pain is a common orthopaedic complaint. If not treated correctly, it can lead to chronic morbidity and disability. Plantar fasciitis is diagnosed clinically. Advanced imaging is rarely required and used to exclude underlying sinister pathology. Osteochondromas of the calcaneum are rare. In symptomatic patients, excision can improve outcomes.

- Citation: Koh D, Goh Y, Yeo N. Calcaneal osteochondroma masquerading as plantar fasciitis: An approach to plantar heel pain - A case report and literature review. World J Orthop 2019; 10(9): 339-347

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-5836/full/v10/i9/339.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5312/wjo.v10.i9.339

Heel pain is a common orthopaedic complaint, constituting about 15% of foot pain[1]. 1 in 8 people aged 50 years and older complain of heel pain, with more than half reporting that the severity is disabling[2].

The various aetiologies of heel pain can be broadly classified into mechanical, neurological, traumatic and degenerative causes with the most common cause being mechanical[3,4]. Accurate diagnosis can be challenging, owing to the complex anatomy and their interdependent mechanical relationships as well as vulnerable pain generators present in the foot[5]. Heel pain is best defined by the Heel Pain Committee of the American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons as pain either over the posterior or plantar aspect of the foot[4]. For the purpose of this article, focus will be on plantar heel pain.

As with all foot and ankle pathologies, a good grasp of anatomy, clinical acuity, detailed history taking as well as physical examination are key to achieving an accurate diagnosis. Astute application of investigative modalities aid in confirming the diagnosis. Conversely, inappropriate treatment can lead to worsening or chronic pain that can result in morbidity[2]. In this case report, we aim to share our clinical experience in managing one such patient whose plantar heel pain was refractory to all treatment modalities offered. We present an unusual case of chronic heel pain secondary to osteochondroma.

A 41-year-old Malay gentleman who works as a hospital porter presented with a long-standing history of left plantar heel pain.

His gastrocnemius was also noted to be tight with positive Silfverskiöld test. He was treated for plantar fasciitis and tight gastrocnemius and underwent extensive physiotherapy sessions targeted at gastrocnemius stretching. He was started on anti-inflammatory and analgesic medications. However, his symptoms persisted, and he underwent left gastrocnemius release and endoscopic plantar fascia release. This provided temporal relief of his symptoms, and he was able to return to work.

Two and half years later, he presented with similar symptoms of left heel pain. His gastrocnemius was once again assessed to be tight demonstrating limited dorsiflexion in the absence of ankle osteoarthritis. A repeated minimally invasive gastrocnemius release was performed. He underwent a prolonged recovery with enforced rest and time off work, which improved his symptoms. However, his symptoms quickly reoccurred upon return to work.

He is obese (BMI: 31 kg/m2), has hyperlipidaemia but reports no history of diabetes or gout.

Patient ambulated with an antalgic gait. On physical assessment, his gastrocnemius remained tight with a positive Silfverskiöld test. Tenderness around the plantar aspect of the calcaneum was non-specific and found along the distribution of the plantar fascia insertion.

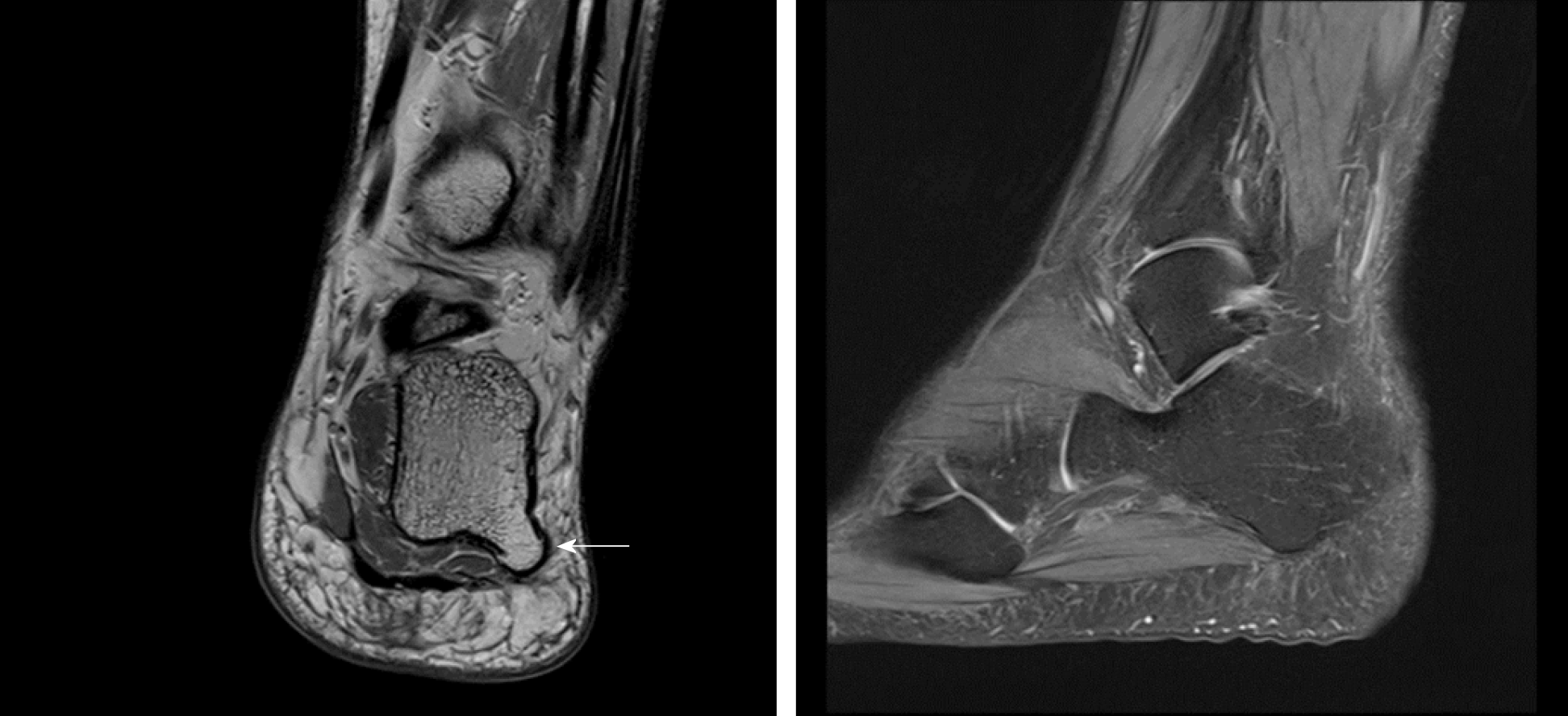

Foot and calcaneal radiographs showed normal bony relationships of the foot with no features of arthritis (Figure 1). No fractures or obvious lesions were noted. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the left foot was performed. It reported the absence of plantar fascia thickening as well as no signal alteration in the adjacent soft tissue or bone marrow. MRI did reveal a pedunculated bony protrusion arising from the posterolateral plantar aspect of the calcaneus measuring 1.1 cm × 0.9 cm, which was consistent with an osteochondroma (Figure 2). Computed tomography scan was organised to better evaluate this lesion (Figure 3).

Osteochondroma of the calcaneum with a concomitant gastrocnemius contracture.

Decision for surgical excision of left calcaneal lesion was made in view of chronic discomfort and limited relief from two other previous procedures. A mini-incision was made centred over the posterolateral border of calcaneum. A soft tissue flap was raised allowing access to the lesion. The bony lesion was excised en bloc and sent for histological analysis. Layered closure was attempted and wound dressed with Jones dressing. Patient was kept on non-weight bearing over the left lower limb before progressing to full weight bearing once the wound healed. Histology reported the lesions as a nodular lesion with mature lamellar bone consistent with a matured osteochondroma.

The patient was followed up closely and remains pain-free 12 mo after surgery. He is back to work and very satisfied with the surgery.

This patient presented with typical signs and symptoms of plantar fasciitis, a common cause of heel pain especially amongst middle-aged patients[6]. Plantar fasciitis is a condition attributed to biomechanical stress of the plantar fascia and its calcaneal insertion. Risk factors of developing plantar fasciitis involve those subjecting the plantar fascia to excessive biomechanical stress. Being obese is a well-documented risk factor[7-9]. Abnormal strain on the windlass mechanism of the foot results in excessive plantar fascia tendon loading and subsequent injury[10]. In non-athletic individuals, patients with BMI ≥ 27 kg/m2 are 3.7 times more likely to suffer from plantar heel pain[7]. In addition, this patient had a tight gastrocnemius[8] as well as a job requiring excessive push-off force to manually transport heavy carts, patients and machines around the hospital. Tight gastrocnemius limits ankle dorsiflexion, thereby producing increased strain on the plantar fascia during the gait cycle[11-13]. Pes cavus is another anatomical risk factor. Patients who have pes cavus have a reduced distance between the calcaneus and the metatarsal heads and rigid relationships between both bony and soft tissue structures[14].

The initial management for plantar fasciitis is conservative. In keeping with the literature, this patient was started on a course of plantar fascia as well as gastrocnemius stretching with a physiotherapist[11,15]. DiGiovanni et al[16,17] demonstrated significant pain relief after 8 wk of plantar fascia specific stretches as compared to gastrocnemius stretches alone. Coupled with the use of non-inflammatory and analgesia medications, off-loading orthotics, heel cups and adequate rest, these treatments form the backbone of plantar fasciitis management[4,5,18].

However, our patient remained symptomatic after a year of conservative management and decided to undergo endoscopic plantar fasciotomy and gastrocnemius release. This surgery offered significant relief in the acute setting. Plantar fasciotomy is the technique of choice in recalcitrant plantar fasciitis[19-22]. In a survey of 64 patients who underwent plantar fasciotomy, Wheeler et al[22] reported 84% of patients were satisfied or very satisfied, with almost three quarters of patients experiencing greater than 80% pain relief. However, owing to varying techniques described within the literature (namely open, mini-open and endoscopic ablation), there remains a paucity of good quality evidence supporting its role[21]. Most agree with the use of the medial open approach releasing the medial third of the plantar fascia[23,24], although there is a growing number of studies showing comparable results using endoscopic plantar fasciotomy[5,25].

Proximal medial gastrocnemius release in the treatment of refractory plantar fasciitis has also shown excellent results without the complications associated with plantar fasciotomy[20,24,26]. This technique was conceived after DiGiovanni et al[27] reported plantar foot pain associated with gastrocnemius contracture and Barouk et al[24] demonstrated the safe surgical technique most authors now perform.

However, results can be unpredictable, especially in patients with chronic heel pain[28]. Our patient returned complaining of similar symptoms after two and half years. The use of advanced imaging modalities, such as ultrasound and MRI is not necessary in diagnosing plantar fasciitis. Toomey et al[29] demonstrated poor correlation between plantar fascia thickness and plantar heel pain. Therefore, most authors believe that plantar fasciitis is a clinical diagnosis[5,24,29,30]. In the case above however, recalcitrant heel pain despite surgical intervention is a red flag warranting further investigation[4,5]. In addition, should the tenderness not be localised to the plantar fascia insertion or if the clinical picture appears inconsistent, then advanced imaging would be prudent.

In a diagnostically challenging case, astute clinical reasoning is key. Most heel pain arises from soft tissue structures such as tendons, fascia and nerves around the calcaneus and less commonly from bone and apophyses[3]. Plantar foot pain pathologies are often mechanical in nature[31].

The authors propose key considerations when approaching heel pain (Table 1). Location, age, precipitating events and nature of symptoms are all important clues to deriving an accurate diagnosis. Pinpointing the location of greatest discomfort is the most useful way of arriving at a diagnosis; it narrows potential differentials and focuses history taking and clinical examination towards structures underlying the site[30]. Patients are encouraged to point a finger at the location of greatest discomfort and through the application of clinical anatomy enquire about exacerbating factors as well as perform respective provocation manoeuvres (Table 1).

| Location | Asking the patient to point with a finger over the point of greatest discomfort allows for narrowing of diagnosis. Subsequent provocation tests or history enquiring of exacerbating factors will provide greater clarity regarding the underlying pathology[30]. |

| Age | In the middle aged (> 45 years old) and elder patients (> 65 years old), degenerative causes such as tendinopathies should be considered[32-34,49]. Whereas in the young, traumatic or overuse injuries such as stress fractures and acute tendinitis are more common[31,36-38]. |

| Trauma and stress injuries | Fundamental to most orthopaedic history-taking, a recent traumatic injury should be ascertained. Radiographic evaluation to rule out fractures should there be a positive history of trauma[4]. In addition, nature of activity as well as occupation will provide insight as to whether patients are at risk of repetitive stress. Athletes as well as manual laborers are predisposed to repetitive strain injuries or tendinitis. |

| Pain characteristic | Characterising pain allows assessment of whether the pain is mechanical or non-mechanical. Start-up pain coupled with progressive worsening with activities may suggest a degenerative or inflammatory cause[30], whilst pain at rest and in the night may suggest a more sinister pathology. |

| Red flags | Whilst rare, it is crucial to exclude sinister causes of plantar heel pain. Tumour: Constitutional symptoms like loss of appetite and loss of weight as well as pain disrupting sleep are red flags suggestive of more systemic pathology[50]. Prompt and advanced imaging modalities are warranted. Infection: Classic features of inflammation – calor, dolor, rubor and tumour coupled with systemic symptoms of fever and malaise are suggestive of an infective process. Both radiological and laboratory tests are crucial in establishing diagnosis as well as evaluating its severity. |

| Others | Neurologic: Patients with compressive neuropathy can present with foot discomfort. In the presence of paraesthesia or numbness, it would be prudent to screen the spine for potential nerve root compression. Rheumatologic: Patients with inflammatory arthritis can present with heel pain. In patients with polyarthropathy, laboratory investigations looking at inflammatory and autoimmune markers are advisable. |

Age is another useful tool in diagnosing heel pain. Almost a quarter of the population aged 45 years and older suffer from foot pain[32]. In the middle aged and elderly, osteoarthritis and tendinopathies as well as plantar fasciitis are more common[24,33,34]. Scher et al[35] reported increasing incidence of plantar fasciitis with increasing age of United States military service members suggesting that the loss of heel-pad elasticity and its ability to “shock-absorb” results in excessive strain to the plantar fascia. Whereas, in the younger, active populations, traumatic or repetitive stress injuries are more likely[36-38].

In the absence of trauma or a fall, bony injury is less likely. Pain that worsens with activity and pushing off suggests a mechanical origin. However, in a patient with chronic heel pain not improved by surgery, sinister causes such as malignancy or infection need to be excluded. Other considerations include a neurological cause from radicular symptoms, referred pain or even systemic inflammatory pathologies (Table 1).

Bilateral dorsoplantar and lateral weight-bearing foot radiographs are fundamental investigations when assessing foot pain. It offers insight into the foot’s bony relationships and allows comparison with the contralateral limb (Figure 1A). Dedicated calcaneal radiographs provide an unobstructed axial view, commonly obscured by overlapping structures of the foot. The presence of osteochondroma on calcaneal radiographs was not obvious on either foot (Figure 1).

In patients with recalcitrant pain refractory to surgery, advanced imaging, such as MRI or computed tomography scans is indicated to evaluate other causes of pain. MRI would allow better assessment of soft tissue pathology as well as acute bony injury after trauma (Figure 2). On the other hand, computed tomography scans provide good bony definition (Figure 3).

Osteochondromas are the most common benign tumour of the skeleton accounting for 36% to 41% of benign bone tumours[39-41] and affecting about 2% to 3% of the general population[41-43]. However, its presentation in a foot and ankle account for less than 10% of such cases[42-46]. Osteochondromas are benign osseous lesions that originate from the metaphyseal regions of long bones and on histology classically present with normal bony trabeculae with a distinct hyaline cartilage cap[41,42,44]. Most osteochondromas are usually asymptomatic and are incidentally picked up on radiographs[42]. They are commonly found in adolescents and young adults presenting often as a painless mass, but it can be symptomatic as a sequelae of its size causing entrapment of neurovascular structures, restriction of movement and fractures[42,44]. Malignant transformation is rare accounting for less than 1% of osteochondromas[41,47,48]. Its presentation in a skeletally mature adult is rare. To date, only a handful of case reports are found in the literature[42,45,46].

There are many causes of heel pain, with plantar fasciitis being the most common cause. However, in recalcitrant heel pain refractory to both conservative and surgical management, it would be astute to investigate the underlying cause further. Osteochondroma of the calcaneum is uncommon but a potential cause of debilitating plantar heel pain. Surgical excision can improve symptoms and reduce plantar heel pain.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Orthopedics

Country of origin: Singapore

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Bravo Petersen SM, Yu B S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Liu MY

| 1. | Garrow AP, Silman AJ, Macfarlane GJ. The Cheshire Foot Pain and Disability Survey: a population survey assessing prevalence and associations. Pain. 2004;110:378-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chatterton BD, Muller S, Roddy E. Epidemiology of posterior heel pain in the general population: cross-sectional findings from the clinical assessment study of the foot. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2015;67:996-1003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tu P. Heel Pain: Diagnosis and Management. Am Fam Physician. 2018;97:86-93. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Thomas JL, Christensen JC, Kravitz SR, Mendicino RW, Schuberth JM, Vanore JV, Weil LS Sr, Zlotoff HJ, Bouché R, Baker J; American College of Foot and Ankle Surgeons heel pain committee. The diagnosis and treatment of heel pain: a clinical practice guideline-revision 2010. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2010;49:S1-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 268] [Cited by in RCA: 262] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lareau CR, Sawyer GA, Wang JH, DiGiovanni CW. Plantar and medial heel pain: diagnosis and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22:372-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Buchbinder R. Clinical practice. Plantar fasciitis. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2159-2166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 324] [Cited by in RCA: 302] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | van Leeuwen KD, Rogers J, Winzenberg T, van Middelkoop M. Higher body mass index is associated with plantar fasciopathy/'plantar fasciitis': systematic review and meta-analysis of various clinical and imaging risk factors. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50:972-981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Irving DB, Cook JL, Young MA, Menz HB. Obesity and pronated foot type may increase the risk of chronic plantar heel pain: a matched case-control study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007;8:41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hill JJ, Cutting PJ. Heel pain and body weight. Foot Ankle. 1989;9:254-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Fuller EA. The windlass mechanism of the foot. A mechanical model to explain pathology. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2000;90:35-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bolívar YA, Munuera PV, Padillo JP. Relationship between tightness of the posterior muscles of the lower limb and plantar fasciitis. Foot Ankle Int. 2013;34:42-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Carlson RE, Fleming LL, Hutton WC. The biomechanical relationship between the tendoachilles, plantar fascia and metatarsophalangeal joint dorsiflexion angle. Foot Ankle Int. 2000;21:18-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Erdemir A, Hamel AJ, Fauth AR, Piazza SJ, Sharkey NA. Dynamic loading of the plantar aponeurosis in walking. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:546-552. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Bolgla LA, Malone TR. Plantar fasciitis and the windlass mechanism: a biomechanical link to clinical practice. J Athl Train. 2004;39:77-82. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Sweeting D, Parish B, Hooper L, Chester R. The effectiveness of manual stretching in the treatment of plantar heel pain: a systematic review. J Foot Ankle Res. 2011;4:19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Digiovanni BF, Nawoczenski DA, Malay DP, Graci PA, Williams TT, Wilding GE, Baumhauer JF. Plantar fascia-specific stretching exercise improves outcomes in patients with chronic plantar fasciitis. A prospective clinical trial with two-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1775-1781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | DiGiovanni BF, Nawoczenski DA, Lintal ME, Moore EA, Murray JC, Wilding GE, Baumhauer JF. Tissue-specific plantar fascia-stretching exercise enhances outcomes in patients with chronic heel pain. A prospective, randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:1270-1277. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Lim AT, How CH, Tan B. Management of plantar fasciitis in the outpatient setting. Singapore Med J. 2016;57:168-70; quiz 171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Brown JN, Roberts S, Taylor M, Paterson RS. Plantar fascia release through a transverse plantar incision. Foot Ankle Int. 1999;20:364-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Abbassian A, Kohls-Gatzoulis J, Solan MC. Proximal medial gastrocnemius release in the treatment of recalcitrant plantar fasciitis. Foot Ankle Int. 2012;33:14-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Rompe JD. Plantar fasciopathy. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev. 2009;17:100-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wheeler P, Boyd K, Shipton M. Surgery for Patients With Recalcitrant Plantar Fasciitis: Good Results at Short-, Medium-, and Long-term Follow-up. Orthop J Sports Med. 2014;2:2325967114527901. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kitaoka HB, Alexander IJ, Adelaar RS, Nunley JA, Myerson MS, Sanders M. Clinical rating systems for the ankle-hindfoot, midfoot, hallux, and lesser toes. Foot Ankle Int. 1994;15:349-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3199] [Cited by in RCA: 3113] [Article Influence: 100.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Monteagudo M, de Albornoz PM, Gutierrez B, Tabuenca J, Álvarez I. Plantar fasciopathy: A current concepts review. EFORT Open Rev. 2018;3:485-493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Bader L, Park K, Gu Y, O'Malley MJ. Functional outcome of endoscopic plantar fasciotomy. Foot Ankle Int. 2012;33:37-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Monteagudo M, Maceira E, Garcia-Virto V, Canosa R. Chronic plantar fasciitis: plantar fasciotomy versus gastrocnemius recession. Int Orthop. 2013;37:1845-1850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | DiGiovanni CW, Kuo R, Tejwani N, Price R, Hansen ST, Cziernecki J, Sangeorzan BJ. Isolated gastrocnemius tightness. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84:962-970. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Martin RL, Irrgang JJ, Conti SF. Outcome study of subjects with insertional plantar fasciitis. Foot Ankle Int. 1998;19:803-811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Toomey EP. Plantar heel pain. Foot Ankle Clin. 2009;14:229-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Alvarez-Nemegyei J, Canoso JJ. Heel pain: diagnosis and treatment, step by step. Cleve Clin J Med. 2006;73:465-471. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Agyekum EK, Ma K. Heel pain: A systematic review. Chin J Traumatol. 2015;18:164-169. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Thomas MJ, Roddy E, Zhang W, Menz HB, Hannan MT, Peat GM. The population prevalence of foot and ankle pain in middle and old age: a systematic review. Pain. 2011;152:2870-2880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Menz HB, Dufour AB, Casey VA, Riskowski JL, McLean RR, Katz P, Hannan MT. Foot pain and mobility limitations in older adults: the Framingham Foot Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2013;68:1281-1285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Menz HB, Tiedemann A, Kwan MM, Plumb K, Lord SR. Foot pain in community-dwelling older people: an evaluation of the Manchester Foot Pain and Disability Index. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006;45:863-867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Scher DL, Belmont PJ, Bear R, Mountcastle SB, Orr JD, Owens BD. The incidence of plantar fasciitis in the United States military. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:2867-2872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Sherman KP. The foot in sport. Br J Sports Med. 1999;33:6-13. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Outerbridge AR, Micheli LJ. Overuse injuries in the young athlete. Clin Sports Med. 1995;14:503-516. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Sammarco GJ. Soft tissue conditions in athletes' feet. Clin Sports Med. 1982;1:149-155. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Wodajo FM. Top five lesions that do not need referral to orthopedic oncology. Orthop Clin North Am. 2015;46:303-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Dahlin DC, Beabout JW. Dedifferentiation of low-grade chondrosarcomas. Cancer. 1971;28:461-466. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Sandell LJ. Multiple hereditary exostosis, EXT genes, and skeletal development. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91 Suppl 4:58-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Blitz NM, Lopez KT. Giant solitary osteochondroma of the inferior medial calcaneal tubercle: a case report and review of the literature. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2008;47:206-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Griffiths HJ, Thompson RC, Galloway HR, Everson LI, Suh JS. Bursitis in association with solitary osteochondromas presenting as mass lesions. Skeletal Radiol. 1991;20:513-516. [PubMed] |

| 44. | Sella EJ, Chrostowski JH. Calcaneal osteochondromas. Orthopedics. 1995;18:573-574; discussion 574-575. [PubMed] |

| 45. | Nogier A, De Pinieux G, Hottya G, Anract P. Case reports: enlargement of a calcaneal osteochondroma after skeletal maturity. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;447:260-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Koplay M, Toker S, Sahin L, Kilincoglu V. A calcaneal osteochondroma with recurrence in a skeletally mature patient: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:7013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Murphey MD, Choi JJ, Kransdorf MJ, Flemming DJ, Gannon FH. Imaging of osteochondroma: variants and complications with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2000;20:1407-1434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 528] [Cited by in RCA: 480] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | de Souza AM, Bispo Júnior RZ. Osteochondroma: ignore or investigate? Rev Bras Ortop. 2014;49:555-564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Dunn JE, Link CL, Felson DT, Crincoli MG, Keysor JJ, McKinlay JB. Prevalence of foot and ankle conditions in a multiethnic community sample of older adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:491-498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 324] [Cited by in RCA: 346] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Flanagan AM, Lindsay D. A diagnostic approach to bone tumours. Pathology. 2017;49:675-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Scott A, Khan KM, Cook JL, Duronio V. What is "inflammation"? Are we ready to move beyond Celsus? Br J Sports Med. 2004;38:248-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |