Published online Oct 10, 2017. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v8.i5.420

Peer-review started: June 6, 2017

First decision: June 27, 2017

Revised: July 5, 2017

Accepted: August 16, 2017

Article in press: August 17, 2017

Published online: October 10, 2017

Processing time: 114 Days and 4.4 Hours

Here we report a patient diagnosed with small cell lung cancer after first presenting with parathyroid hormone-related peptide-induced hypercalcemic pancreatitis and developed walled-off necrosis that resulted in disruption of the main pancreatic duct. Disconnected duct syndrome (DDS) is a rare syndrome that occurs when the main pancreatic duct exocrine flow is disrupted resulting in leakage of pancreatic enzymes and further inflammatory sequela. To date, no prior reports have described DDS occurring with paraneoplastic reactions. Diagnostic imaging techniques and therapeutic interventions are reviewed to provide insight into current approaches to DDS.

Core tip: Acute recurrent pancreatitis flares should raise concern for disconnected duct syndrome (DDS). This case is the first reported case of DDS caused by paraneoplastic hypercalcemia. Paraneoplastic syndromes may predispose patients to prolonged hypercalcemic pancreatitis and in turn, may predispose patients to DDS. Furthermore, this case report reviews the current approach and treatment difficulties of DDS as well as pancreatic walled-off necrosis.

- Citation: Montminy EM, Landreneau SW, Karlitz JJ. First report of small cell lung cancer with PTHrP-induced hypercalcemic pancreatitis causing disconnected duct syndrome. World J Clin Oncol 2017; 8(5): 420-424

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2218-4333/full/v8/i5/420.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5306/wjco.v8.i5.420

Disconnected duct syndrome (DDS) is a pancreatic syndrome where the main pancreatic duct is occluded and pancreatic exocrine flow leaks into the pancreatic parenchyma[1]. This syndrome frequently results in further inflammatory reactions such as sepsis, development of pseudocysts, and fistulizing disease. Etiologies of DDS are more commonly from mass-like lesions such as large pseudocysts, walled-off necrosis, or neoplasms obstructing the main pancreatic duct[1]. DDS often is difficult to treat due to narrow or complete occlusions requiring cannulation and increased surgical morbidity and mortality. Additionally, this case report discusses a unique cause of DDS and the current approaches used for diagnosis and treatment. To date, this is the first report of a DDS being related to a paraneoplastic syndrome.

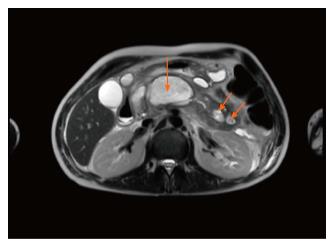

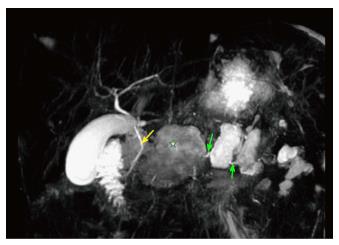

A 38-year-old man with newly diagnosed small cell lung cancer (SCLC) presented in late July 2016 with acute onset epigastric pain, nausea, and vomiting. He was admitted one month prior for acute pancreatitis secondary to a calcium of 13.7 mg/dL (normal 8.4-10.3 mg/dL). He denied alcohol history or previous gall stones at that time, and imaging work up was only positive for pancreatic inflammation and a lung mass determined by biopsy to be SCLC. No evidence of bone metastasis was seen on imaging. During the July 2016 admission, vital signs at presentation were blood pressure 143/99 mmHg, heart rate 120 beat/min, respiratory rate 14 breaths/min, oxygen saturation 100%, temperature 36.6 °C, and physical exam was only positive for epigastric tenderness. Labs demonstrated a serum lipase of 2030 U/L (normal < 90 U/L), serum calcium of 11 mg/dL (normal 8.4-10.3 mg/dL), parathyroid hormone less than 9 pG/mL (normal 12-65 pG/mL) and parathyroid-related peptide of 3.9 pmol/L (normal < 2 pmol/L). Triglycerides were normal. Abdominal ultrasound revealed no evidence of gallstones. MRI of the abdomen with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) showed multiple cystic areas with rim enhancement replacing large portions of the pancreatic body with the largest centered in the mid-body of the pancreas measuring 3.5 cm × 6.2 cm compressing the main pancreatic duct as well as a 2 cm × 4.3 cm collection extending into the pancreatic groove (Figure 1). MRCP displayed complete lack of enhancement of the main pancreatic duct (Figure 2). A diagnosis of DDS was made based off of these findings. Development of the walled-off necrosis and pancreatic inflammation was thought to be secondary to repeated paraneoplastic-induced pancreatitis episodes. ERCP-guided cannulation of main pancreatic duct past the pancreatic head was unsuccessful due to complete occlusion of the duct (Figure 3). Pancreatic duct stent placement was unsuccessful. Endoscopic ultrasound visualized the walled off necrosis, but transmural drainage was avoided due to symptomatic improvement with conservative management. The patient was managed conservatively with pain management and bisphosphonates over the following 24 wk until cholecystectomy and surgical necrosectomy were performed. The surgery was uncomplicated. Currently, the patient was transitioned to home hospice due to progression of his cancer.

Acute pancreatitis is defined by the Atlanta Classification as having: (1) Typical pain; (2) imaging showing pancreatic inflammation; and (3) elevation in amylase or lipase > 3 × the upper limit of normal. Two of the three criteria must be present to confirm the diagnosis[2]. Acute pancreatitis can be complicated by the formation of fluid collections which have been defined and characterized by the 2012 revised Atlanta Classification (Table 1)[2]. Major distinguishing features of fluid collections are the required time for formation, the presence of an encapsulating inflammatory wall, and heterogeneity[2]. An acute peripancreatic fluid collection (APFC) is a collection of adjacent fluid that develops within the first four weeks of the initial pancreatitis[2]. APFC is not contained by a visible encapsulating inflammatory wall and is a homogeneous collection with fluid density[2]. In contrast, a pancreatic pseudocyst is a fluid collection usually outside of the pancreas and typically requires four weeks or more to develop[2]. A pseudocyst has a visible encapsulating inflammatory wall and is homogeneous with only fluid components[2]. If acute pancreatitis progresses to necrotizing pancreatitis, an acute necrotic collection (ANC) can develop. An ANC develops usually less than four weeks from initial event and does not have visible encapsulating walls. ANC can be distinguished from an APFC by a heterogeneous appearance from localized liquid and necrotic pancreatic tissue. After approximately four weeks, an ANC will develop an encapsulated inflammatory wall which is termed a walled-off necrosis (WON). A WON will continue to have a heterogeneous appearance from accumulated fluid and necrotic pancreatic tissue[2].

| Structural complications of acute pancreatitis[2] | |

| Acute peripancreatic fluid collection | Defined as peripancreatic fluid within the first 4 wk of interstitial edematous pancreatitis Homogeneous collection with fluid density No visible encapsulating wall around fluid collection Adjacent to pancreas |

| Pancreatic pseudocyst | Defined as an encapsulated fluid collection usually forming > 4 wk from initial pancreatitis event with visible inflammatory wall typically outside the pancreas with minimal or no necrotic features forming Homogeneous fluid density with no non-liquid components |

| Acute necrotic collection | Defined as a fluid collection with variable amounts of fluid and necrosis without a visible encapsulating wall Only can occur with necrotizing pancreatitis Can involve pancreatic parenchyma and/or peripancreatic tissue Heterogeneous and non-liquid density of varying degrees |

| Walled-off necrosis | Defined as a mature collection of pancreatic and/or peripancreatic necrosis with an encapsulating inflammatory wall typically requiring > 4 wk from initial pancreatitis to form Only can occur with necrotizing pancreatitis Heterogeneous with liquid and non-liquid density with varying degrees of loculation |

Acute recurrent pancreatitis is a clinical condition that is defined as two or more attacks of pancreatitis without evidence of underlying chronic pancreatitis[3]. Acute recurrent pancreatitis is often attributed to gallstones, alcohol ingestion, or idiopathic causes[3]. Furthermore, acute recurrent pancreatitis can progress to necrotizing pancreatitis and develop inflammatory fluid collections that obstruct pancreatic duct drainage, termed DDS. DDS should be considered on a differential diagnosis particularly when a patient presents with repeated bouts of pancreatitis and enlarging pancreatic fluid collections. DDS is a syndrome that starts with an episode of acute pancreatitis that typically develops a large fluid collection or necrosis. This initial fluid collection results in compression of the main pancreatic duct. Disruption of the main pancreatic duct flow, most commonly in the neck or body of the pancreas[4], results in blockage and leakage of distal drainage of pancreatic enzymes. Leakage of these enzymes into the pancreatic parenchyma results in further inflammatory sequela such as more fluid collections, fistulas, or sepsis. Causes of DDS all result in a significant narrowing or complete occlusion of the main pancreatic duct. More frequently encountered causes of duct obstruction are large pseudocysts, necrotic lesions, trauma, and abdominal neoplasms[4,5]. Less commonly, causes such as intra-ductal pancreatic mucinous neoplasm or calculi can result in DDS. Of note, acute recurrent pancreatitis as a presenting feature of SCLC is rare and if present, pancreatitis is more commonly from metastatic lesions obstructing the pancreatic duct rather than PTHrP-induced hypercalcemia[6]. Hypercalcemia results typically from either elevated PTHrP production or osteolytic activity from bone metastasis. Paraneoplastic hypercalcemia is most commonly associated with squamous cell carcinoma of the lung as opposed to small cell lung cancer[7]. The presence of paraneoplastic hypercalcemia in lung cancer has been associated with poorer survival outcomes[8]. No previous cases have reported DDS developing from PTHrP-induced hypercalcemic pancreatitis. There is no clear consensus on which cause of pancreatitis is most likely to result in DDS. This patient possessed persistent hypercalcemia and an aggressive malignancy, both risk factors for pancreatitis, and in turn, risks for development of DDS.

Patients presenting with acute pancreatitis will often have already received an abdominal ultrasound and/or CT abdomen with and without contrast in the emergency department to visualize causes of pancreatic inflammation. In patients with suspected DDS, MRCP is particularly useful by providing detailed mapping of the pancreaticobiliary ducts[4]. ERCP is no longer routinely used for diagnostic purposes as MRCP can provide the same information without the risks associated with ERCP, but is undertaken with therapeutic intentions such as relieving obstructions via stent placement and displaying resolution of obstruction on repeat fluoroscopy[9]. Additionally, endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is utilized for more accurate visualization of the pancreatic duct and ultrasound-guided drainage of large fluid collections causing obstruction of the duct[10]. For cases of DDS involving WON, endoscopic necrosectomy can be coupled with EUS to relieve obstructions by debriding and opening necrotic septa through gastric or duodenum access[11].

Whenever possible, definitive intervention is delayed 4 wk or more to allow organization of necrotic collections and development of an encapsulating wall[12]. Initially, if the patient is clinically stable, a minimally invasive approach can be performed to relieve ductal compression with endoscopic/percutaneous approaches favored over open surgical necrosectomy[12,13]. If endoscopic interventions are unsuccessful, surgical intervention (i.e. necrosectomy, Roux-en-Y, or debridement) is required to relieve obstructions. While data suggests that minimally invasive approaches are superior to surgical intervention for necrosectomy, whether endoscopic or surgical intervention is superior for DDS is still a subject of debate[14,15]. For DDS, endoscopic intervention is typically first-line and less invasive than surgery, but success is dependent on cannulation of narrow strictures and stent placement in cases of ERCP and optimal positioning of lesions for drainage in cases of EUS[14]. Surgical interventions are often successful at relieving obstructions, but often are associated with higher morbidity and mortality compared to endoscopy[11,13,15]. This case demonstrates the approach to a unique case of DDS and highlights the difficulty associated with treatment of DDS. Additionally, this case is evidence of the importance of earlier detection of lesions prior to complete ductal obstructions. In complete pancreatic duct obstructions, ERCP efficacy may be limited and result in patients having to undertake greater morbidity and mortality risks to relieve obstructions.

A 38-year-old man with small cell lung cancer presented with acute onset epigastric pain, nausea and vomiting.

Tenderness in the epigastric region of the abdomen and tachycardia.

Acute hypercalcemic pancreatitis, acute recurrent pancreatitis, gastric ulcer, erosive gastropathy, cholelithiasis, choledocholithiasis.

Labs demonstrated lipase 2030 U/L (normal < 90 U/L), serum calcium of 11 mg/dL (normal 8.4-10.3 mg/dL), parathyroid hormone less than 9 pG/mL (normal 12-65 pG/mL), parathyroid-related peptide of 3.9 pmol/L (normal < 2 pmol/L), and normal triglycerides.

Magnetic resonance imaging with magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography showed multiple cystic areas with rim enhancement replacing large portions of the pancreatic body with the largest centered in the mid-body of the pancreas measuring 3.5 cm × 6.2 cm compressing the main pancreatic duct as well as a 2 cm × 4.3 cm collection extending into the pancreatic groove.

Unsuccessful endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography-guided main pancreatic stent placement followed by successful surgical necrosectomy and cholecystectomy.

Disconnected duct syndrome (DDS) is rare syndrome that often presents with recurrent pancreatitis flares. The syndrome is more commonly caused by mass lesions obstructing the main pancreatic duct. Paraneoplastic hypercalcemia is more often associated with squamous cell lung cancer as opposed to small cell lung cancer.

DDS is a pancreatic syndrome where the main pancreatic duct is occluded and pancreatic exocrine flow leaks into the pancreatic parenchyma. This syndrome frequently results in further inflammatory reactions such as sepsis, development of pseudocysts, and fistulizing disease.

Acute recurrent pancreatitis should raise concerns for DDS due to exocrine leakage into pancreatic parenchyma causing repeated inflammatory reactions. Although less common than squamous cell lung cancer, small cell lung cancer can result in paraneoplastic hypercalcemia which can expose patients to prolonged risks of pancreatitis. This prolonged risk of pancreatitis may increase the risk for develop of DDS.

This is an interesting case for physician.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Chang CC, Yu SP S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Fischer TD, Gutman DS, Hughes SJ, Trevino JG, Behrns KE. Disconnected pancreatic duct syndrome: disease classification and management strategies. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;219:704-712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS; Acute Pancreatitis Classification Working Group. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4932] [Cited by in RCA: 4342] [Article Influence: 361.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (45)] |

| 3. | Testoni PA. Acute recurrent pancreatitis: Etiopathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:16891-16901. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Manikkavasakar S, AlObaidy M, Busireddy KK, Ramalho M, Nilmini V, Alagiyawanna M, Semelka RC. Magnetic resonance imaging of pancreatitis: an update. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:14760-14777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 5. | Debi U, Kaur R, Prasad KK, Sinha SK, Sinha A, Singh K. Pancreatic trauma: a concise review. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:9003-9011. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Hussain A, Adnan A, El-Hasani S. Small cell carcinoma of the lung presented as acute pancreatitis. Case report and review of the literature. JOP. 2012;13:702-704. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Kanaji N, Watanabe N, Kita N, Bandoh S, Tadokoro A, Ishii T, Dobashi H, Matsunaga T. Paraneoplastic syndromes associated with lung cancer. World J Clin Oncol. 2014;5:197-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 8. | Takai E, Yano T, Iguchi H, Fukuyama Y, Yokoyama H, Asoh H, Ichinose Y. Tumor-induced hypercalcemia and parathyroid hormone-related protein in lung carcinoma. Cancer. 1996;78:1384-1387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kozarek RA. Endoscopic therapy of complete and partial pancreatic duct disruptions. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1998;8:39-53. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Ergun M, Aouattah T, Gillain C, Gigot JF, Hubert C, Deprez PH. Endoscopic ultrasound-guided transluminal drainage of pancreatic duct obstruction: long-term outcome. Endoscopy. 2011;43:518-525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Thompson CC, Kumar N, Slattery J, Clancy TE, Ryan MB, Ryou M, Swanson RS, Banks PA, Conwell DL. A standardized method for endoscopic necrosectomy improves complication and mortality rates. Pancreatology. 2016;16:66-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | van Grinsven J, van Santvoort HC, Boermeester MA, Dejong CH, van Eijck CH, Fockens P, Besselink MG; Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Timing of catheter drainage in infected necrotizing pancreatitis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;13:306-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, Bakker OJ, Hofker HS, Boermeester MA, Dejong CH, van Goor H, Schaapherder AF, van Eijck CH, Bollen TL. A step-up approach or open necrosectomy for necrotizing pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1491-1502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1038] [Cited by in RCA: 1037] [Article Influence: 69.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Machado N. Disconnected Duct Syndrome: A Bridge to Nowhere. Pan Disord Ther. 2015;5:153. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Nadkarni NA, Kotwal V, Sarr MG, Swaroop Vege S. Disconnected Pancreatic Duct Syndrome: Endoscopic Stent or Surgeon’s Knife? Pancreas. 2015;44:16-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |