Published online Dec 28, 2014. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v6.i12.932

Revised: September 2, 2014

Accepted: October 31, 2014

Published online: December 28, 2014

Processing time: 341 Days and 0.8 Hours

Focal fatty change of the segment IV of the liver has been attributed to local systemic venous inflow replacing the portal venous supply, which could develop or be accentuated after gastrectomy. However, focal fatty change due to aberrant pancreaticoduodenal vein that developed after cholecystectomy has never been reported. We report a 30-year-old man with such a rare lesion, which was initially misdiagnosed as a hepatocellular carcinoma, but was confirmed on computed tomography during selective gastroduodenal arteriography. The lesion disappeared 12 mo later without any intervention.

Core tip: We herein present a case with a history of chronic hepatitis C, who initially was misdiagnosed to have a well-differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma, but was finally diagnosed to have a focal fatty change due to aberrant pancreaticoduodenal vein that developed after cholecystectomy.

- Citation: Osame A, Mitsufuji T, Kora S, Yoshimitsu K, Morihara D, Kunimoto H. Focal fatty change in the liver that developed after cholecystectomy. World J Radiol 2014; 6(12): 932-936

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v6/i12/932.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v6.i12.932

Various pseudolesion observed on computed tomography (CT) during arterial portography (CTAP) have been reported and described; some of these have been attributed to venous drainage to the hepatic parenchyma other than portal venous blood (so-called “the third inflow”), such as aberrant right gastric vein (ARGV), cholecystic vein, aberrant pancreaticoduodenal vein (APDV), and epigastric/paraumbilical veins[1,2]. What should be noted is some of these focal fatty change may develop or be accentuated after gastrectomy due to alteration of the local venous blood flow around the region of the porta hepatis.

We herein present a case with a history of chronic hepatitis C (CHC), who initially was misdiagnosed to have a well-differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma (wHCC), but was finally diagnosed to have a focal fatty change due to APDV that developed after cholecystectomy. The nomenclature used in present report to describe hepatic segments is based on Couinaud’s system[3].

A 30-year-old man with a history of CHC was admitted to our hospital with a suspected diagnosis of wHCC. The patient had past history of acute lymphocytic leukemia at the age of six, which showed complete response to chemotherapy; blood transfusion was performed at that time, however, and liver dysfunction was found at the age of 15, which turned out to be due to CHC. Interferon therapy was then given, and sustained virological response was successfully achieved at the age of 25. During the clinico-radiological follow-up thereafter, he was found to have gallbladder polyps, and underwent cholecystectomy in our institution 6 mo before this admission. Pre-cholecystectomy multidetector-row CT (MDCT) and ultrasonography (US) of the liver had shown no liver mass (not shown).

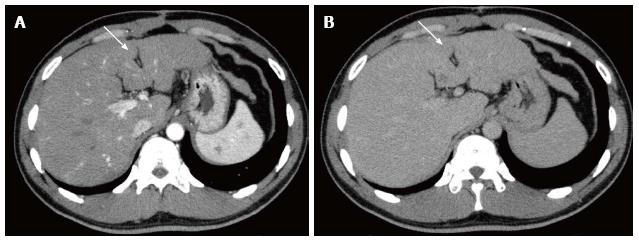

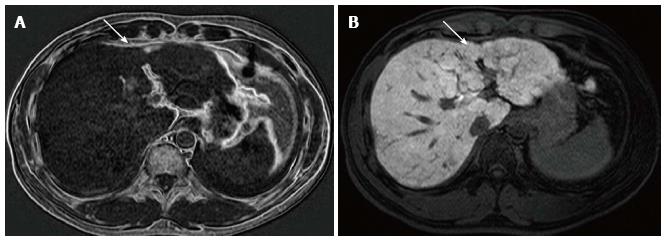

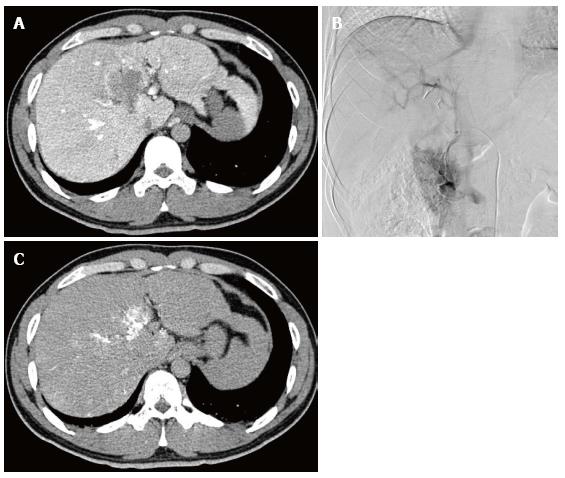

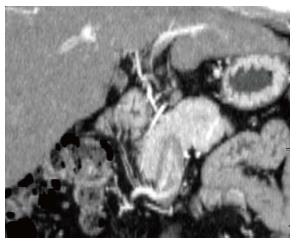

On admission, laboratory data showed only slightly elevated transaminases, but otherwise were within normal limits. MDCT (Aquilion 64, Toshiba, Tokyo, Japan) demonstrated an ill-defined, irregularly shaped lesion of decreased attenuation in segment IV (S4) measuring 13 mm in diameter, which showed poor enhancement after the injection of contrast medium (Figure 1). The lesion was seen as an echogenic area on US (not shown). On magnetic resonance (MR) imaging (1.5 T clinical unit, Intera Achieva Nova Dual, Philips, Eindhoven, Netherland), the lesion showed isointensity on T1- and T2-weighted images (T1WI, T2WI, respectively) and apparent signal reduction on the out-of-phase images as compared to in-phase images of chemical shift imaging (CSI), suggesting the presence of fat. On the dynamic phases after gadoxetate disodium (Primovist, Bayer-Schering Pharmaceuticals, Berlin, Germany) administration, no to poor enhancement was observed. On hepatobiliary phase, the lesion showed diminished uptake of gadoxetate disodium, which was slightly smaller in size than the fatty area shown on CSI (Figure 2). Judging from these information, a diagnosis of wHCC with slight fatty change was made and surgical resection was planned. On CTAP via superior mesenteric artery, which was performed as a preoperative workup, demonstrated an ill-defined portal perfusion defect in S4, which was significantly larger in size than the fatty area shown on MDCT or MR imaging. CT during proper hepatic arteriography, on the other hand, revealed no significant abnormal vascular lesion at the corresponding area. Meticulous review of the venous phase of the celiac angiography suggested the presence of an APDV coursing toward S4 of the liver, and then, selective catheterization of GD artery was performed. The venous phase of computed tomography during selective gastroduodenal arteriography (CTGDA) was obtained, which confirmed that the portal perfusion defect located in S4 as seen on CTAP was a pseudolesion caused by APDV drainage (Figure 3). The patient was discharged without any specific intervention. Retrospective review of MDCT images, both before cholecystectomy and immediately before the admission, revealed the presence of this APDV (Figure 4).

Serial follow-up US and MR imaging (not shown) showed that the lesion gradually diminished in size and became faint in appearance, then disappeared completely at 20 mo after surgery, supporting the non-neoplastic nature of the lesion. The appearance of APDV remained unchanged on these follow-up images.

Couinaud reported the existence of vessels running parallel to the common bile duct and hepatic artery, just anterior to the portal vein and originating from the pancreaticoduodenal, right gastric and cholecystic veins, naming them the parabiliary venous system (PVS)[4]. These veins usually join in the main trunk or major branches of the portal venous system but occasionally enter the liver directly around the porta hepatis (ARGV or APDV), sometimes resulting in isolated perfusion.

These aberrant venous inflows has been attributed to the presence of focal fatty change of the S4.

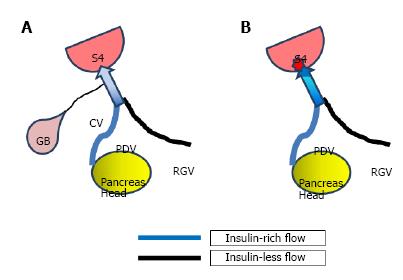

The pathogenesis of fatty infiltration in the liver is multifactorial. Some authors have speculated a mechanism related to the insulin level in the venous blood, as follows. It is considered that free fatty acids are the major substrates for hepatic triglyceride and ketone body synthesis. Insulin inhibits the oxidation of fatty acids to ketone bodies and promote esterification of fatty acids into triglycerides that accumulate in hepatocytes. The area mainly supplied from the pancreaticoduodenal vein directly entering the liver may be influenced by a high local concentration of insulin that inhibits the formation of ketone bodies, thus favoring accumulation of triglycerides in hepatocytes[5].

Pseudolesions due to APDV has been reported sporadically[2,5,6], but one report has suggested its incidence around 2%[7]. In the presented case, S4 was shown as a defect of the portal venous supply on CTAP, while the venous phase of the GD arteriography showed an APDV running toward this segment along the course of the portal vein: CTGDA showed an APDV blood directly entering the defective area of portal venous supply. Because the area with decreased portal perfusion on CTAP was ill-defined and larger in size than the actual fatty area, this area was considered to be perfused both by APDV and portal venous blood reciprocally, and only the small area with the highest insulin concentration (presumably the entering point of APDV) became fatty.

One notable point in this particular case is that the focal fatty area in S4 was not seen 6 mo before on CT, but became apparent after cholecystectomy. Similar phenomenon has been reported in patients with PVS who underwent gastrectomy[7], the mechanism of which may also be applicable to the current case as well. That is, before the cholecystectomy, the venous blood from the region of the head of the pancreas, which contains insulin that is known to have a steatogenic effect on hepatocytes, as mentioned earlier, is diluted by venous blood from the gall bladder that does not contain insulin before reaching S4 of the liver. After the cholecystectomy, this diluting blood flow disappeared and venous blood from the region of the pancreas head with highly concentrated insulin directly drained S4, where intense focal fatty change may occur[7] (Figure 5). The reason why this focal fatty area became obliterated on the follow-up is unclear, but again, similar sequential change of focal fatty area has been reported in patients with PVS who underwent gastrectomy[7]. The exact mechanism of this of this phenomenon, however, is still unknown and will require further investigation.

One limitation in this study is lack of pathological proof of fatty change at S4. We dared not to perform percutaneous biopsy of the lesion and decided to follow the patient, considering the difficulty in making the pathological diagnosis of wHCC only on the biopsy specimens[8]. We believe the clinico-radiological data, namely CTGDA findings and non-progressive nature of the lesion on the follow-up, may sufficiently support the non-neoplastic etiology of the fatty area in S4 in this particular patient.

In conclusion, we presented a case with a focal fatty area in S4 of the liver, caused by APDV, that developed after cholecystectomy. Radiologists and clinicians need to be aware of this phenomenon and should not mistake these lesions for HCCs or metastases.

We thank Professor Shotaro Sakisaka, Chair of Department of Gastroenterology, Faculty of Medicine, Fukuoka University, for providing clinical information of the patient in this report.

A 30-year-old man with a history of chronic hepatitis C with a suspected diagnosis of well-differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma (wHCC).

Judging from clinical date, computed tomography and magnetic resonance (MR) information, a diagnosis of wHCC with slight fatty change.

Focal fatty change, metastasis.

laboratory data showed only slightly elevated transaminases, but otherwise were within normal limits.

Multidetector-row computed tomography (CT) and MRI findings suggested wHCC with slight fatty change. The venous phase of computed tomography during selective gastroduodenal arteriography was obtained, which confirmed that the portal perfusion defect located in segment IV as seen on CT during arterial portography was a pseudolesion caused by aberrant pancreaticoduodenal vein drainage.

The patient was discharged without any specific intervention.

Focal fatty change may develop or be accentuated after gastrectomy due to alteration of the local venous blood flow around the region of the porta hepatis.

The third inflow: venous drainage to the hepatic parenchyma other than portal venous blood.

Radiologists and clinicians need to be aware of this phenomenon and should not mistake these lesions for HCCs or metastases.

The manuscript entitled Focal fatty change in the medial segment of the liver due to aberrant pancreatico-duodenal venous drainage that developed after cholecystectomy: A Case Report is well-presented and written. It is also a rare case which shows that it can cause confusion with HCC based on certain diagnostic procedures.

P- Reviewer: Sazci A S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Matsui O, Takahashi S, Kadoya M, Yoshikawa J, Gabata T, Takashima T, Kitagawa K. Pseudolesion in segment IV of the liver at CT during arterial portography: correlation with aberrant gastric venous drainage. Radiology. 1994;193:31-35. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Yoshimitsu K, Honda H, Kuroiwa T, Irie H, Aibe H, Shinozaki K, Masuda K. Unusual hemodynamics and pseudolesions of the noncirrhotic liver at CT. Radiographics. 2001;21 Spec No:S81-S96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Couinaud C. Le Foie: etudes anastomoique et chirugicales. Paris: Masson 1957; . |

| 4. | Couinaud C. The parabiliary venous system. Surg Radiol Anat. 1988;10:311-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fukukura Y, Fujiyoshi F, Inoue H, Sasaki M, Hokotate H, Baba Y, Nakajo M. Focal fatty infiltration in the posterior aspect of hepatic segment IV: relationship to pancreaticoduodenal venous drainage. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:3590-3595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nakayama T, Yoshimitsu K, Masuda K. Pseudolesion in segment IV of the liver with focal fatty deposition caused by the parabiliary venous drainage. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2000;24:259-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yoshimitsu K, Irie H, Kakihara D, Tajima T, Asayama Y, Hirakawa M, Ishigami K, Noshiro H, Kakeji Y, Honda H. Postgastrectomy development or accentuation of focal fatty change in segment IV of the liver: correlation with the presence of aberrant venous branches of the parabiliary venous plexus. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2007;41:507-512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Durand F, Regimbeau JM, Belghiti J, Sauvanet A, Vilgrain V, Terris B, Moutardier V, Farges O, Valla D. Assessment of the benefits and risks of percutaneous biopsy before surgical resection of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2001;35:254-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |