Published online Jul 28, 2013. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v5.i7.253

Revised: May 26, 2013

Accepted: June 8, 2013

Published online: July 28, 2013

Processing time: 191 Days and 7.9 Hours

AIM: To retrospectively analyze changes in clinical indication, referring medical specialty and detected pathology for small bowel double-contrast examinations.

METHODS: Two hundred and forty-one (n = 143 females; n = 98 males; 01.01.1990-31.12.1990) and 384 (n = 225 females; n = 159 males; 01.01.2004-31.12.2010) patients underwent enteroclysis, respectively. All examinations were performed in standardized double-contrast technique. After placement of a nasojejunal probe distal to the ligament of Treitz, radiopaque contrast media followed by X-ray negative distending contrast media were administered. Following this standardized projections in all four abdominal quadrants were acquired. Depending on the detected pathology further documentation was carried out by focused imaging. Examination protocols were reviewed and compared concerning requesting unit, indication and final report.

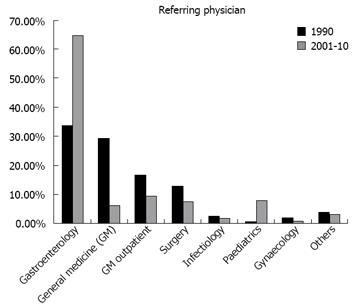

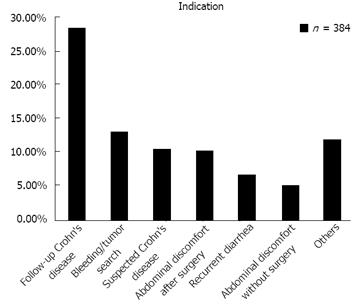

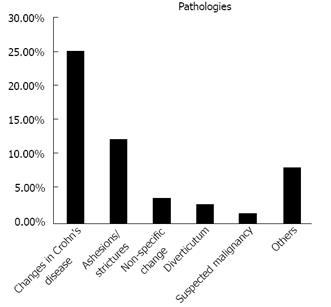

RESULTS: Two hundred and forty-one examinations in 1990 faced an average of 55 examinations per year from 2004-2010. There was an increase of examinations for gastroenterological (33.6% to 64.6%) and pediatric (0.4% to 7.8%) indications while internal (29.0% to 6.0% for inpatients and from 16.6% to 9.1% for outpatients) and surgical (12.4% to 7.3%) referrals significantly decreased. “Follow-up of Crohn’s disease” (33.1%) and “bleeding/tumor search” (15.1%) represented the most frequent clinical indications. A total of 34% (1990) and 53.4% (2004-2010) examinations yielded pathologic findings. In the period 01.01.2004 -31.12.2010 the largest proportion of pathological findings was found in patients with diagnosed Crohn’s disease (73.5%), followed by patients with abdominal pain (67.6% with history of surgery and 52.6% without history of surgery), chronic diarrhea (41.7%), suspected Crohn’s disease (39.5%) and search for gastrointestinal bleeding source/tumor (19.1%). The most common pathologies diagnosed by enteroclysis were “changes in Crohn’s disease” (25.0%) and “adhesions /strictures” (12.2%).

CONCLUSION: “Crohn’s disease” represents the main indication for enteroclysis. The relative increase of pathologic findings reflects today’s well directed use of enteroclysis.

Core tip: The double contrast examination of the small intestine by enteroclysis is a well-established diagnostic tool for small bowel diagnostics. Comparing the number of performed investigations, it becomes obvious that modern endoscopic and radiological methods lead to an increased replacement of classical radiological methods such as enteroclysis. On the other hand the increasing proportion of pathological findings, as shown in the presented study, justifies the continued use of enteroclysis for dedicated clinical indications in a structured diagnostic chain.

- Citation: Maataoui A, Vogl TJ, Jacobi V, Khan MF. Enteroclysis: Current clinical value. World J Radiol 2013; 5(7): 253-258

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v5/i7/253.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v5.i7.253

Due to the anatomical and physiological characteristics of the small bowel the diagnostic accessibility of conventional endoscopic procedures is limited to the duodenum and terminal ileum[1]. Although modern endoscopic techniques such as single-ballon enteroscopy, double-balloon enteroscopy, spiral enteroscopy or video capsule endoscopy allow an almost complete investigation of the small bowel they remain subject to technical and economic limitations[2].

The double contrast examination of the small intestine by enteroclysis is a well-established diagnostic tool for small bowel diagnostics[3], especially for infectious bowel diseases[3-5]. The increasing incidence of inflammatory bowel diseases in the industrialized world is leading to a rising interest in this modality[6,7]. Due to its indirect impression of mucosal structures the double contrast technique allows the detection of very small ulcers, erosions and aphtoid lesions as early signs of common pathologies[8]. The dynamic examination approach permits a functional small bowel assessment; this represents a major advantage over alternate diagnostic modalities. Since the rate of pathological findings is directly dependant on the degree of suspected small bowel disease enteroclysis is inappropriate as a screening procedure.

Because of the non-negligible radiation exposure[9] enteroclysis has to be enclosed in an overall diagnostic concept. In case of abdominal disorders, if clinical symptoms do not suggest small bowel pathology, gastroduodenoscopy or colonoscopy should be preferred as an initial step in the diagnostic chain. In suspected small bowel disease enteroclysis is added to the diagnostic scheme in a stepwise diagnostic approach[4].

Today enteroclysis competes with modern endoscopic and radiological modalities with their specific advantages and disadvantages[4]. At the same time declining numbers of examinations result in a continuous lack of experience of young radiologists in terms of technical implementation and diagnostic assessment. This development will hardly boost the value of enteroclysis and may lead to a declining number of referrals in the future. The aim of this study was to evaluate the currently changing clinical value of enteroclysis considering referring medical specialties and detected pathologies.

The data from 625 patients were retrospectively analyzed. A total of n = 241 (n = 143 females, n = 98 males; investigation period 01.01.1990-31.12.1990) and n = 384 (n = 225 females, n = 159 males; investigation period 01.01.2004-31.12.2010) patients were evaluated for referring physicians and percentage of pathological findings.

In addition, the data from the period 01.01.2004- 31.12.2010 were evaluated in terms of medical indication and detected pathology. This information was not available for the first period of investigation in 1990.

All examinations were performed in standardized double-contrast technique. Examiners were 4th year radiological residents directly supervised by a staff radiologist with more than 10 years of experience in gastrointestinal imaging. After placement of a nasojejunal probe (Guerbet, Sulzbach, Germany) distal to the ligament of Treitz, radiopaque contrast media (Barium, Guerbet, Sulzbach, Germany) followed by X-ray negative distending contrast media (Methylcellulose, Guerbet, Sulzbach, Germany) were administered. All contrast media were applied with a contrast media pump (KMP 2000, Guerbet, Sulzbach, Germany) using standardized flow-rates of 80-120 mL/min. Following this standardized projections in all four abdominal quadrants were acquired. Depending on the detected pathology further documentation was carried out by focused imaging.

There was a decline of examinations from a total of 241 in the period 01.01.1990-31.12.1990 to an average of 55 examinations between 01.01.2004-31.12.2010.

In the overall patient collective only in gastroenterology and in paediatrics a significant increase in patient referrals between both time periods was observed, i.e., 33.6% (81/241) to 64.6% (248/384) in gastroenterology and 0.4% (1/241) to 7.8% (30/384) in paediatrics. In contrast to these referrals from general medicine decreased from 29.0% (70/241) to 6.0% (23/384) for inpatients and from 16.6% (40/241) to 9.1% (35/384) for outpatients. Referrals for surgical inpatients decreased from 12.4% (30/241) to 7.3% (28/384). The number of referrals from all other departments including gynaecology and infectious diseases remained unchanged during the entire evaluation (Figure 1).

Thirty-four percent of studies in the period 01.01.1990-

31.12.1990 and 53.4% of studies in the period 01.01.2004 -31.12.2010 showed a pathological finding. In the latter group, the vast majority of pathologies was diagnosed in patients with known Crohn’s disease (73.5%), followed by patients with abdominal pain (67.6% with history of surgery and 52.6% without history of surgery), chronic diarrhea (41.7%), suspected Crohn’s disease (39.5%) and search for gastrointestinal bleeding source/tumor (19.1%) (Table 1).

| Clinical question | Percentage of pathological findings |

| Control of Crohn’s disease | 73.5 |

| Suspected Crohn’s disease | 39.5 |

| Search for GI bleeding source | 19.1 |

| Abdominal pain (positive history of surgery) | 67.6 |

| Abdominal pain (without history of surgery) | 52.6 |

| Chronic diarrhea | 41.7 |

| Overall percentage of pathological findings | 53.4 |

“Follow-up of Crohn’s disease” was the most frequent indication (33.1%, 127/384). It was followed by the “bleeding/tumor search (15.1%, 58/384)”, “suspected Crohn’s disease” (12.2%, 47/384), “abdominal discomfort after visceral surgery” (12.0%, 46/384), “recurrent diarrhea” (7.8%, 30/384), “abdominal discomfort without history of visceral surgery” (6.0%, 23/384) and “others” (13.8%, 53/384) (Figure 2).

The most common pathologies diagnosed by enteroclysis were “changes in Crohn’s disease” (25.0%, 96/384), “adhesions/strictures” (12.2%, 47/384), “non-specific changes” (3.6%, 14/384), “diverticulum of small bowel” (2.9%, 11/384), “suspected malignancy” (1.6%, 6/384) and “other findings” (8.1%, 31/384) (Figure 3).

The aim of this study was to evaluate the frequency of referrals from various medical specialties and to perform an assessment of the diagnostic value of enteroclysis.

Comparing the number of investigations shows a clear trend: While in 1990 the 241 examinations of the small bowel by enteroclysis were conducted, there was an average of only 55 investigations per year for the period of 2004-2010. The reasons are an increasing use of modern endoscopic procedures[2] which allow a direct visualization of mucosal structures as well as the evolution of alternative imaging techniques such as ultrasound, computer tomography and magnetic resonance imaging[2].

We believe the shift in referral base from surgery to gastroenterology and pediatrics may have an influence on the number of examinations performed. While surgically referred examinations decreased, we found an increase of gastroenterologic and pediatric indications. The referrals, particularly for Crohns patients, may be a reflection of a change in attitude of treating physicians due to the emergence of novel immunomodulatory drug therapy in this disease. This was also established by the authors of the “European evidence based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease: current management”[10]. They confirm that the surgical treatment strategies have lost significantly in importance in the last decade because of developments in drug therapy of chronic inflammatory bowel disease.

With regards to the increase in examinations for the pediatric patients the analysis of demographic data provides important information[11-13]. While in 1990 the youngest patient who underwent enteroclysis was 16 years old, in the years 2004-2010 already 4-year-old children were examined. In 1990 6.6% of patients were 0 to 20 years old, in 2004 to 2010 already 10.9% of patients were in this age group. These data are consistent with the epidemiological trend of chronic inflammatory bowel diseases, which shows that about one third of patients are younger than 20 years of age at the time of diagnosis[14,15]. With the expected increase in number of young patients, alternative radiological modalities without radiation exposure such as ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging are prefered[16]. The decreasing referrals from general medicine confirm the consistent trend for specialization in internal medicine. General medicine physicians usually refer their patients with gastroenterological complaints to a gastroenterologic specialist to initiate further investigations. For the small bowel this is increasingly achieved with the improvement and further development of endoscopic procedures[2,17,18]. If necessary, at this point, enteroclysis is added to the diagnostic process. The described approach will ultimately lead to a selection of the patients referred to the radiologist in which a detailed diagnostic workup was performed already. This leads to a more efficient utilization of diagnostic resources and necessarily to an increasing proportion of pathological findings as shown in this study: While in 1990 34% of the investigations showed pathologic findings it was 53.4% between 2004-2010. Antes et al[19] confirmed an increase of pathological findings in the period of 1998- 2003 from 46% to 57%, respectively. Older data from the 80’s confirm a lower proportion of pathological findings which was between 34.4% and 40%[20-22].

The indications “suspected Crohn’s disease” and “follow-up of Crohn’s disease” were the most common indications in this patient population (2004-2010). At the same time, they are the patient group with the highest percentage of pathological findings. The reason for that is an increasing incidence of chronic inflammatory bowel disease in western industrialized nations[6,7] and the high spatial resolution of enteroclysis. The latter allows the detection of early mucosal lesions with an excellent sensitivity and specificity[23]. The continuous technical development of modern imaging methods lead to an increased use in the investigation of Crohn’s disease. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), therefore, is gaining importance by providing direct visualization of mural and extramural changes as well as utilizing multiplanar imaging[2]. Because of the superior soft tissue contrast MRI imaging is superior to computed tomography (CT) concerning enteral pathologies[2,24]. In addition, the absence of radiation exposure, especially among young and very young patients who have to undergo multiple follow-ups for chronic disease monitoring, is of high value. Both modalities (MRI and CT) are limited by the visualization of mucosal details and cannot perform dynamic studies[25]. Modern endoscopic procedures, such as double balloon endoscopy are important diagnostic and therapeutic procedures because they can obtain biopsies and dilate stenotic bowel sections.

The second most frequent indication was “tumor/bleeding”, which in a fifth of cases turned out to have pathological findings. Taking into account that in this patient population enteroclysis stands at the end of the diagnostic chain these are satisfactory results which are consistent with the data of other research groups and justify the use of enteroclysis[24-27]. None the less investigation of gastrointestinal bleeding remains the domain of endoscopy. Success rates of 54%[28] for the push-enteroscopy and 73%[17] for the double-ballon endoscopy are key arguments. Promising data is supplied by video capsule endoscopy, which achieved a sensitivity of 88.9% and a specificity of 95% in patients with negative gastroscopy and colonoscopy, respectively[29]. With an increasing availability and affordability this modality will be the future reference standard for the detection of otherwise undetectable gastrointestinal bleeding[30].

Studies done for the indication “recurrent diarrhea” yielded a pathological finding in 41.7% such as Crohn’s or Whipples disease (inflammatory), celiac disease (allergic) and diverticulums (functional).

In “unclear abdominal complaints” the double contrast examination of the small bowel resulted in 48.6% (known prior surgery) and in 52.6% (no prior surgery) of cases in pathological findings. In particular the high number of detected pathologies in the latter group differs significantly from previous results. In patients with unclear abdominal complaints Lankisch et al[31] and Malik et al[27] detected 6% and 16.7% pathological findings by enteroclysis. The high percentage of detected pathologies in this study may be explained by the fact that 63.2% of the referrals were with suspected small bowel obstruction. This illustrates impressively the correlation of an exact clinical indication and the efficiency of the used radiological procedure. If the radiological findings stay inconspicuous, the use of video capsule endoscopy provides no diagnostic gain: In 20 patients with unexplained abdominal pain and normal upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, colonoscopy, push-enteroscopy and radiological workup, Bardan et al [27] detected no pathology using video capsule endoscopy.

In conclusion, modern endoscopic and radiological methods lead to an increased replacement of classical radiological methods such as enteroclysis. The results presented in this paper justify the continued use of enteroclysis for dedicated clinical indications in a structured diagnostic chain. However the diagnostic benefit rely on a sound clinical work up.

The double contrast examination of the small intestine by enteroclysis is a well-established diagnostic tool for small bowel diagnostics. Especially the increasing incidence of inflammatory bowel diseases in the western world is leading to a regaining interest in this modality. Today enteroclysis competes with modern endoscopic and radiological modalities, such as single-balloon enteroscopy, double-balloon enteroscopy and magnetic resonance imaging. The aim of the presented study was to evaluate the currently changing clinical value of enteroclysis.

Modern endoscopic and radiological methods lead to an increased replacement of classical radiological methods such as enteroclysis. “Crohn’s disease” represents the main indication for enteroclysis. The relative increase of pathological findings reflects today’s well directed use of enteroclysis. However the diagnostic benefit relies on a sound clinical work up.

Despite modern endoscopic and radiological modalities the study results justify the use of enteroclysis for dedicated clinical indications in a structured diagnostic chain.

Enteroclysis: Enteroclysis is a fluoroscopic X-ray of the small intestine. After placement of a nasojejunal probe, radiopaque contrast media followed by X-ray negative distending radiocontrast are infused. Images are taken in real-time as the contrast moves through the small intestine. Due to its indirect impression of mucosal structures the double contrast technique allows the detection of early signs of common pathologies.

In the retrospective study “Enteroclysis: current clinical value” the authors report on enteroclysis as diagnostic option in small bowel disease. The well elaborated study shows that enteroclysis has its diagnostic value for dedicated clinical indications.

P- Reviewer Domagk D S- Editor Song XX L- Editor A E- Editor Lu YJ

| 1. | Antes G, Eggemann F. Small bowel radiology: Introduction and atlas. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer Berlin 1986; . |

| 2. | Tennyson CA, Semrad CE. Advances in small bowel imaging. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2011;13:408-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Dye CE, Gaffney RR, Dykes TM, Moyer MT. Endoscopic and radiographic evaluation of the small bowel in 2012. Am J Med. 2012;125:1228.e1-1228.e12. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Gatta G, Di Grezia G, Di Mizio V, Landolfi C, Mansi L, De Sio I, Rotondo A, Grassi R. Crohn’s disease imaging: a review. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012:816920. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Lenze F, Wessling J, Bremer J, Ullerich H, Spieker T, Weckesser M, Gonschorrek S, Kannengiesser K, Rijcken E, Heidemann J. Detection and differentiation of inflammatory versus fibromatous Crohn’s disease strictures: prospective comparison of 18F-FDG-PET/CT, MR-enteroclysis, and transabdominal ultrasound versus endoscopic/histologic evaluation. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:2252-2260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, Ghali WA, Ferris M, Chernoff G, Benchimol EI, Panaccione R, Ghosh S, Barkema HW. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:46-54.e42; quiz e30. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Prideaux L, Kamm MA, De Cruz PP, Chan FK, Ng SC. Inflammatory bowel disease in Asia: a systematic review. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:1266-1280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rollandi GA, Biscaldi E, DeCicco E. Double contrast barium enema: technique, indications, results and limitations of a conventional imaging methodology in the MDCT virtual endoscopy era. Eur J Radiol. 2007;61:382-387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Maataoui A, Reusch E, Khan MF, Gurung J, Thalhammer A, Ackermann H, Mulert-Ernst R, Vogl TJ, Jacobi V. [Comparison of analog and digital fluoroscopy devices regarding patient radiation exposure in enteroclysis]. Rofo. 2008;180:246-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Travis SP, Stange EF, Lémann M, Oresland T, Chowers Y, Forbes A, D’Haens G, Kitis G, Cortot A, Prantera C. European evidence based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease: current management. Gut. 2006;55 Suppl 1:i16-i35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 440] [Cited by in RCA: 403] [Article Influence: 21.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hope B, Shahdadpuri R, Dunne C, Broderick AM, Grant T, Hamzawi M, O’Driscoll K, Quinn S, Hussey S, Bourke B. Rapid rise in incidence of Irish paediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Arch Dis Child. 2012;97:590-594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Martín-de-Carpi J, Rodríguez A, Ramos E, Jiménez S, Martínez-Gómez MJ, Medina E. Increasing incidence of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease in Spain (1996-2009): the SPIRIT Registry. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:73-80. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Schildkraut V, Alex G, Cameron DJ, Hardikar W, Lipschitz B, Oliver MR, Simpson DM, Catto-Smith AG. Sixty-year study of incidence of childhood ulcerative colitis finds eleven-fold increase beginning in 1990s. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1-6. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Hildebrand H, Finkel Y, Grahnquist L, Lindholm J, Ekbom A, Askling J. Changing pattern of paediatric inflammatory bowel disease in northern Stockholm 1990-2001. Gut. 2003;52:1432-1434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Phavichitr N, Cameron DJ, Catto-Smith AG. Increasing incidence of Crohn’s disease in Victorian children. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18:329-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Paolantonio P, Ferrari R, Vecchietti F, Cucchiara S, Laghi A. Current status of MR imaging in the evaluation of IBD in a pediatric population of patients. Eur J Radiol. 2009;69:418-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | May A, Nachbar L, Schneider M, Ell C. Prospective comparison of push enteroscopy and push-and-pull enteroscopy in patients with suspected small-bowel bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2016-2024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Xin L, Liao Z, Jiang YP, Li ZS. Indications, detectability, positive findings, total enteroscopy, and complications of diagnostic double-balloon endoscopy: a systematic review of data over the first decade of use. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:563-570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Antes G. [Barium examinations of the small intestine and the colon in inflammatory bowel disease]. Radiologe. 2003;43:9-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Antes G, Lissner J. Double-contrast small-bowel examination with barium and methylcellulose. Radiology. 1983;148:37-40. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Rödl W, Possel HM, Prull A, Wunderlich L. [Value of small bowel double contrast enema in clinical interventions]. Radiologe. 1986;26:55-65. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Salomonowitz E, Wittich G, Czembirek H. [Experience with double-contrast examination of the small intestine]. Radiologe. 1983;23:289-294. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Cirillo LC, Camera L, Della Noce M, Castiglione F, Mazzacca G, Salvatore M. Accuracy of enteroclysis in Crohn’s disease of the small bowel: a retrospective study. Eur Radiol. 2000;10:1894-1898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Schmidt S, Felley C, Meuwly JY, Schnyder P, Denys A. CT enteroclysis: technique and clinical applications. Eur Radiol. 2006;16:648-660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Hohl C, Haage P, Krombach GA, Schmidt T, Ahaus M, Günther RW, Staatz G. [Diagnostic evaluation of chronic inflammatory intestinal diseases in children and adolescents: MRI with true-FISP as new gold standard?]. Rofo. 2005;177:856-863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Korman U, Kantarci F, Selçuk D, Cetinkaya S, Kuruğoğlu S, Mihmanli I. Enteroclysis in obscure gastrointestinal system hemorrhage of small bowel origin. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2003;14:243-249. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Malik A, Lukaszewski K, Caroline D, Parkman H, DeSipio J, Banson F, Bazir K, Reddy L, Srinivasan R, Fisher R. A retrospective review of enteroclysis in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding and chronic abdominal pain of undetermined etiology. Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:649-655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Manning-Dimmitt LL, Dimmitt SG, Wilson GR. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal bleeding in adults. Am Fam Physician. 2005;71:1339-1346. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Pennazio M, Santucci R, Rondonotti E, Abbiati C, Beccari G, Rossini FP, De Franchis R. Outcome of patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding after capsule endoscopy: report of 100 consecutive cases. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:643-653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 637] [Cited by in RCA: 604] [Article Influence: 28.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Teshima CW, Kuipers EJ, van Zanten SV, Mensink PB. Double balloon enteroscopy and capsule endoscopy for obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: an updated meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:796-801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 208] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Lankisch PG, Gaetke T, Gerzmann J, Becher R. The role of enteroclysis in the diagnosis of unexplained gastrointestinal symptoms: a prospective assessment. Z Gastroenterol. 1998;36:281-286. [PubMed] |