Published online Oct 28, 2013. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v5.i10.381

Revised: September 2, 2013

Accepted: October 16, 2013

Published online: October 28, 2013

Processing time: 117 Days and 4.2 Hours

Life-threatening hemorrhage rarely occurs from the portal vein following blunt hepatic trauma. Traditionally, severe portal bleeding in this setting has been controlled by surgical techniques such as packing, ligation, and venorrhaphy. The presence of portal hypertension could potentially increase the amount of hemorrhage in the setting of blunt portal vein trauma making it more difficult to control. This case series describes the use of indirect carbon dioxide portography to identify portal hemorrhage. Furthermore, these cases illustrate attempted endovascular treatment utilizing a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in one scenario and transmesocaval shunt coiling of a jejunal varix in the other.

Core tip: The significance of bleeding from a portal venous origin following blunt hepatic trauma in the setting of portal hypertension, the potential role of indirect carbon dioxide venogram in identifying massive portal hemorrhage, and the use of a multiphase computed tomography of the liver in a trauma case with suspected internal bleeding and known portal hypertension are discussed. These cases illustrate attempted endovascular treatment of portal vein injury utilizing a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in one scenario and transmesocaval shunt coiling of a jejunal varix in the other. Further research is needed to elucidate outcomes of portal interventions in the setting of coexisting portal hypertension and hemorrhage.

- Citation: Sundarakumar DK, Smith CM, Lopera JE, Kogut M, Suri R. Endovascular interventions for traumatic portal venous hemorrhage complicated by portal hypertension. World J Radiol 2013; 5(10): 381-385

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v5/i10/381.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v5.i10.381

The hepatic arterial system is a common source of massive hemorrhage from blunt liver trauma[1]. However, significant bleeding from the portal venous vasculature is rare, with a reported incidence of 0.08%-0.10%[2]. The low pressure typically present in the portal system likely accounts for this difference. Portal venous injuries are generally associated with severe injuries affecting adjacent organs that often require surgical treatment. As a result, the mortality associated with portal venous injury following blunt trauma remains dismal, reportedly as high as 57%[2-4]. Intrahepatic portal venous bleeding is surgically controlled by the tamponade effect of peri-hepatic packing. In instances of pre-existing portal hypertension, injury to the portal vein and its tributaries can result in massive hemorrhage and shock. Although transjugular portosystemic shunt (TIPS) can effectively control variceal bleeding secondary to portal hypertension[5], its role in controlling bleeding secondary to blunt trauma remains unclear. These case reports describe two unusual cases of massive hemorrhage from a portal venous source in the setting of portal hypertension and illustrate techniques for diagnosis and potential management.

A 58-year-old man with hepatitis C cirrhosis suffered severe blunt abdominal trauma in a motor vehicle collision. Limited history, which was later available from the family member suggested chronic liver disease due to Hepatitis C for 3 years without known history of gastrointestinal bleeding or hepatic encephalopathy. No prior medical records or images were available for review. He presented with circulatory shock due to massive intraperitoneal hemorrhage. After initial resuscitation, an emergent exploratory laparotomy was performed to control the intra-abdominal bleeding. Operative findings included multiple right hepatic lobe lacerations as well as a 5 cm hepatic mass, presumptively hepatocellular carcinoma. Massive mesenteric congestion due to portal hypertension was seen, and identification of the source of hemorrhage proved difficult. A clamp was placed across the hepatoduodenal ligament, hepatic artery, and portal vein (Pringle maneuver) and the peri-hepatic region was packed. Ongoing hemodynamic instability prompted emergent angiography. The abdomen was left open to unclamp the patient during angiography.

Angiography of the celiac axis, proper hepatic artery, and right hepatic artery did not reveal any active extravasation. However, given the patient’s unstable status and severe right hepatic lobe injury, the arterial branches supplying the inferior segments of the right lobe were embolized using 100-300 micron Embospheres (Merit Medical Systems, Utah) in order to control a possible tumor related hemorrhage. Hemodynamic instability persisted despite arterial embolization, packing, and resuscitation. The portal venous system was subsequently evaluated for source of hemorrhage.

With the catheter in the right hepatic vein, a wedged carbon dioxide venogram demonstrated brisk extravasation of contrast from a branch of the right portal vein (Figure 1A). The right hepatic vein wedged pressure recordings revealed a portosystemic gradient of 50 mmHg (Free = 5 mmHg, wedged = 55 mmHg). Transhepatic access was obtained to the right portal vein. Direct portal venous pressure measurement and portogram confirmed the high portal venous pressure and brisk extravasation of contrast arising from the right branch of portal vein (Figure 1B). A 10 mm × 8 cm Viatorr endoprosthesis (WL Gore associates) was successfully placed across the hepatic tract and the stent was dilated to 10 mm. Following deployment of the stent, the porto-systemic gradient reduced to 0 mmHg. Post-TIPS portal venogram showed drastic reduction in the contrast extravasation from the portal vein (Figure 1C). Unfortunately, during the procedure, the patient’s hemodynamic status further deteriorated, and he developed profound hypotension. The patient was transferred to the ICU for further cardiovascular resuscitation. Both surgical re-exploration and the possibility of portal vein embolization were contemplated. However, the patient expired three hours after the interventional radiology procedure secondary to refractory shock and acidosis.

A 19-year-old man sustained blunt abdominal trauma in a motor vehicle collision and presented with massive hematemesis and shock. The patient’s history was pertinent for a right liver lobe hepatectomy for hepatoblastoma with the creation of a hepatico-jejunostomy at 1 year old. At 4 years of age, he developed extra-hepatic portal hypertension due to the portal vein thrombosis with cavernous transformation of the portal vein; this was treated with a mesocaval shunt. At 17 years old, stenosis of the shunt was identified and treated with angioplasty and stenting; large esophageal varices were also embolized concomitantly.

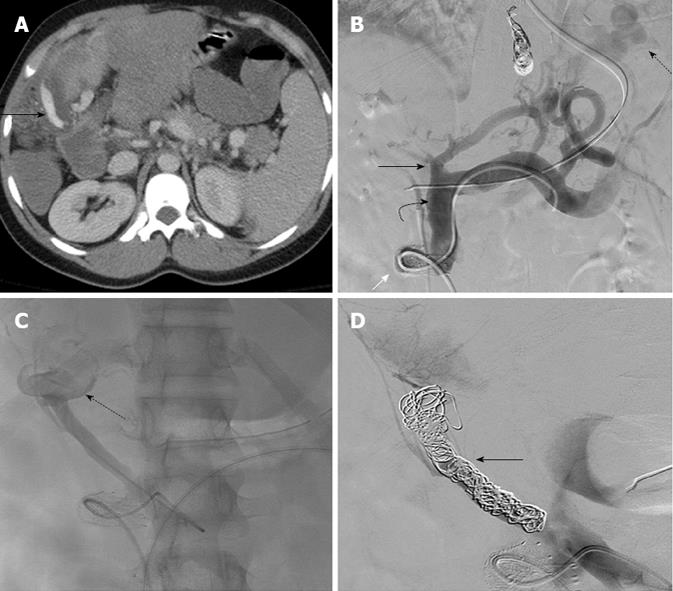

At the time of the traumatic presentation, contrast enhanced computed tomography (CT) revealed possible contrast extravasation from a dilated venous collateral into the peritoneum (Figure 2A). The patient was sent for angiography given ongoing hemodynamic instability. Hepatic and superior mesenteric artery angiography was negative for active extravasation or pseudoaneurysm. Next, the portal circulation was accessed through the preexisting mesocaval shunt. The pressure gradient across the mesocaval shunt measured 4 mmHg. A 5 French, 40 cm Ansel sheath (Cook, Bloomington, Ind) was advanced through the mesocaval shunt. Portal venogram showed a patent mesocaval shunt with severely dilated gastric varices (Figure 2B). Although no clear hemorrhage was identified, these varices were successfully embolized using multiple 6-8 mm Nester (Cook, Bloomington, Ind) coils. Subsequent venogram of a branch of the superior mesenteric vein revealed large venous collaterals in the hepaticojejunostomy loop with active extravasation (Figure 2C). This feeding vein was also successfully embolized using multiple Nester coils (Figure 2D). The patient stabilized after embolization. The remaining post-procedural period was uneventful and the patient was discharged two weeks later. There have been no further episodes of bleeding during the 2 year follow-up period.

Extravasation from an hepatic arterial source is more common, and is effectively managed by arterial embolization. Damage control surgery can be effective at managing hemorrhage in blunt abdominal trauma requiring laparotomy, allowing time for physiological recovery from coagulopathy, shock, and hypothermia[6]. But in cirrhotic patients with blunt abdominal trauma, this approach may prove insufficient. Portal hypertension, coagulopathy, varices, and splenomegaly caused by cirrhosis renders spontaneous arrest of bleeding difficult[7]. Significant bleeding from a portal venous origin is rare, and has a more complex management. In hemodynamically stable patients, primary portal venography, direct reanastomosis, porto-caval anastomosis, interposed grafts, and intraoperative temporary stenting of the injured segment of the portal vein have been performed to achieve continuity without causing mesenteric congestion[2,4,8]. These procedures involve prolonged surgical time, with many deaths resulting from intraoperative exsanguination[9]. Fraga et al[2] report the overall mortality associated with primary repair of the portal vein at 46.7%. A second approach to prompt control of portal hemorrhage involves ligation of the portal vein[9]. When used as a last line resort for controlling the portal hemorrhage, the survival rate is 13%[10]. Acute portal vein ligation increases the portal pressure which can cause mesenteric congestion, systemic hypotension due to sequestration of venous return, and occasionally bowel infarction[11]. The effects of portal ligation in portal hypertensive patients were not reported, however, it is reasonable to speculate that exacerbating the baseline mesenteric congestion in cirrhotic patients would result in even higher mortality rates[10].

Not unexpectedly, mortality following hepatic trauma to the cirrhotic liver correlates with increasing Model for End Stage liver disease (MELD) score. Lin et al[7] studied the outcomes in 34 cirrhotic patients with blunt trauma and concluded that a MELD score of 17 or more correlates with increased post-operative mortality. In the presented case scenarios, portal hypertension may have led to, or at least intensified, massive portal vein hemorrhage.Endovascular treatment such as TIPS could thus potentially provide an alternative or adjunct to surgery in a portal hypertensive patient with proven portal hemorrhage. Although this approach increases the chances of liver failure in high MELD score cases, it also has the potential to avoid operative mortality and morbidity associated with portal venography, as well as avoiding the complications of increased mesenteric congestion caused by portal ligation. The endovascular technique attempted in the first case was based on the extrapolation of the success of emergent TIPS in controlling medically refractive spontaneous massive upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage due to portal hypertension[12]. However, reducing portal pressure using TIPS did not completely stop the extravasation in this patient. If he had been more stable, the next step may have included selective transhepatic portal vein embolization. While this move may have controlled hemorrhage, subsequent liver necrosis and/or fulminant hepatic failure would have been possible complications.

In the second case, the afferent loop of the hepaticojejunostomy was the source of jejunal variceal bleed. Ectopic varices in portal hypertension favor forming at sites of postoperative adhesions[13]. Spontaneous bleeding occurs in only 1%-5% of ectopic varices[14], and this type of hemorrhage is difficult to diagnose, as well as treat, by routine upper gastrointestinal endoscopic techniques. TIPS and balloon occlusion assisted retrograde transvenous obliteration are more effective methods of treating hemorrhage from ectopic varices[15]. The second patient responded well to transmesocaval shunt coiling of the bleeding varix.

In both of the presented case reports, arterial bleeding was ruled out with angiography before proceeding with portal venous evaluation and intervention. CT was not performed in the first patient because of hemodynamic instability, and only a single-phase contrast scan was performed in the second patient. Pre-procedural triple-phase CT in stable trauma patients with known portal hypertension and liver injury could help distinguish arterial versus portal hemorrhage. This could save the time and risks associated with conventional angiography; however, may not be feasible in unstable patients. On single-phase CT, the standard imaging protocol in trauma cases, imaging clues of intra-hepatic portal vein trauma include extension of hepatic laceration through the portal vein, abrupt cut off the portal vessels, vessel wall contour irregularity, and periportal hypodensity[16].

These case reports illustrate the significance of bleeding from a portal venous origin following blunt hepatic trauma in the setting of portal hypertension, and describe some of the challenges associated with diagnosis and treatment. The potential role of indirect carbon dioxide venogram in identifying massive portal hemorrhage was described. However, if clinically permissible, a multiphase CT of the liver could be valuable in differentiating arterial from portal venous hemorrhage as well as planning a potential intervention. Further research and larger case series are clearly desirable to delineate the imaging protocols and to elucidate outcomes of portal interventions in the setting of coexisting portal hypertension and hemorrhage.

P- Reviewers Bergese SD, Rosenthal P S- Editor Zhai HH L- Editor A E- Editor Lu YJ

| 1. | Matthes G, Stengel D, Seifert J, Rademacher G, Mutze S, Ekkernkamp A. Blunt liver injuries in polytrauma: results from a cohort study with the regular use of whole-body helical computed tomography. World J Surg. 2003;27:1124-1130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fraga GP, Bansal V, Fortlage D, Coimbra R. A 20-year experience with portal and superior mesenteric venous injuries: has anything changed? Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2009;37:87-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Pearl J, Chao A, Kennedy S, Paul B, Rhee P. Traumatic injuries to the portal vein: case study. J Trauma. 2004;56:779-782. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Henne-Bruns D, Kremer B, Lloyd DM, Meyer-Pannwitt U. Injuries of the portal vein in patients with blunt abdominal trauma. HPB Surg. 1993;6:163-168. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Boyer TD. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: current status. Gastroenterology. 2003;124:1700-1710. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Rotondo MF, Schwab CW, McGonigal MD, Phillips GR, Fruchterman TM, Kauder DR, Latenser BA, Angood PA. ‘Damage control’: an approach for improved survival in exsanguinating penetrating abdominal injury. J Trauma. 1993;35:375-82; discussion 382-3. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Lin BC, Fang JF, Wong YC, Hwang TL, Hsu YP. Management of cirrhotic patients with blunt abdominal trauma: analysis of risk factor of postoperative death with the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score. Injury. 2012;43:1457-1461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Reilly PM, Rotondo MF, Carpenter JP, Sherr SA, Schwab CW. Temporary vascular continuity during damage control: intraluminal shunting for proximal superior mesenteric artery injury. J Trauma. 1995;39:757-760. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Jurkovich GJ, Hoyt DB, Moore FA, Ney AL, Morris JA, Scalea TM, Pachter HL, Davis JW. Portal triad injuries. J Trauma. 1995;39:426-434. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Stone HH, Fabian TC, Turkleson ML. Wounds of the portal venous system. World J Surg. 1982;6:335-341. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Pachter HL, Drager S, Godfrey N, LeFleur R. Traumatic injuries of the portal vein. The role of acute ligation. Ann Surg. 1979;189:383-385. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Kalva SP, Salazar GM, Walker TG. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for acute variceal hemorrhage. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2009;12:92-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lebrec D, Benhamou JP. Ectopic varices in portal hypertension. Clin Gastroenterol. 1985;14:105-121. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Norton ID, Andrews JC, Kamath PS. Management of ectopic varices. Hepatology. 1998;28:1154-1158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sato T, Akaike J, Toyota J, Karino Y, Ohmura T. Clinicopathological features and treatment of ectopic varices with portal hypertension. Int J Hepatol. 2011;2011:960720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (35)] |

| 16. | Hewett JJ, Freed KS, Sheafor DH, Vaslef SN, Kliewer MA. The spectrum of abdominal venous CT findings in blunt trauma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:955-958. [PubMed] |