Published online Jul 28, 2011. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v3.i7.194

Revised: May 20, 2011

Accepted: May 27, 2011

Published online: July 28, 2011

Varicoceles are often treated with percutaneous embolization, using fibered coils and sclerosing agents, with the latter targeted at occlusion of pre-existing collateral veins. While various methods of surgical and embolization treatment are available, varicoceles may still recur from venous collateralization. We present a case, where following demonstration of complete occlusion of the right and left gonadal veins, direct puncture of the pampiniform venous plexus under ultrasound guidance revealed recurrent varicoceles supplied by anastomoses from the ipsilateral saphenous and femoral veins to the pampiniform plexus. In doing so, we describe a technique of percutaneous pampiniform venography in a case where the pertinent anatomy was not easily demonstrated by other methods.

- Citation: Gendel V, Haddadin I, Nosher JL. Antegrade pampiniform plexus venography in recurrent varicocele: Case report and anatomy review. World J Radiol 2011; 3(7): 194-198

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v3/i7/194.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v3.i7.194

A varicocele is an abnormal dilatation of the pampiniform plexus, the venous drainage system of the testicle. Both surgical and percutaneous routes have provided effective treatment with recurrence rates reported at 1%-20% in the recent literature[1-3]. The cause of recurrence is most frequently demonstrated by retrograde gonadal venography as collateralization of the gonadal vein by retroperitoneal collateral flow. We report the use of ultrasound-guided antegrade venography of the pampiniform plexus, demonstrating an infrequent etiology of varicocele recurrence. We also review the venous drainage of the testicle, including the pertinent anatomy, which is more frequently demonstrated by antegrade venography and more often recognized in the urology literature.

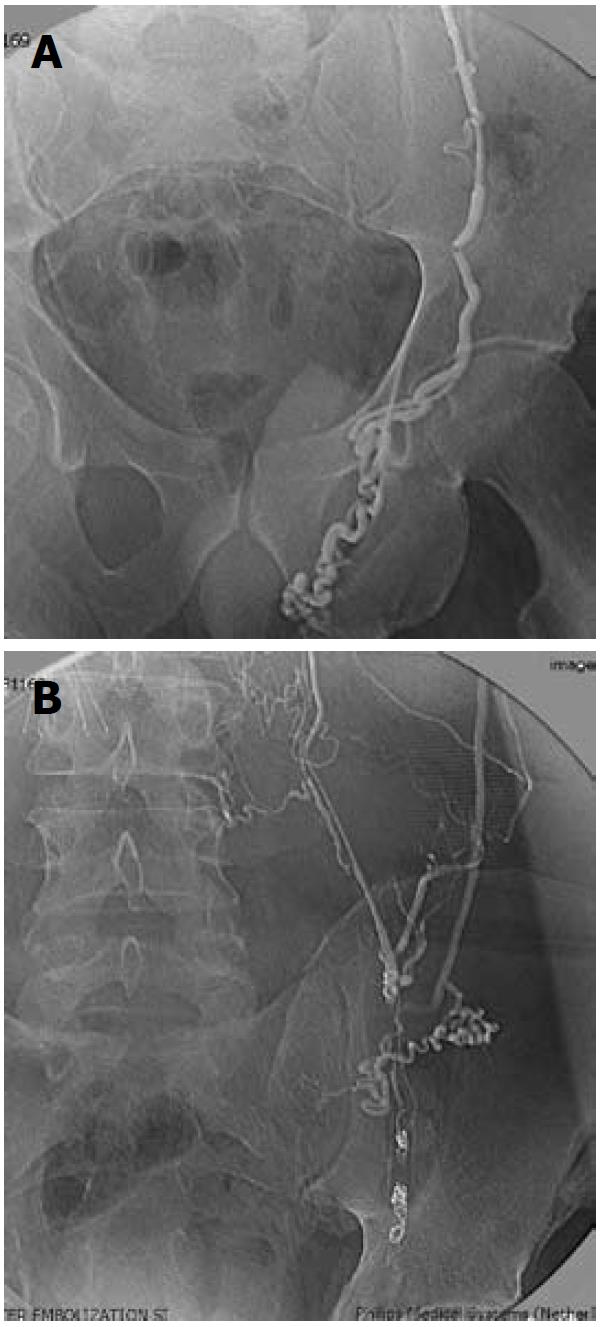

A 45-year-old man with multiple medical problems, including end stage idiopathic dilated non-ischemic cardiomyopathy, with a left ventricular ejection fraction of 20%, presented with unremitting discomfort related to bilateral varicoceles. The patient specifically reported significant bilateral testicular pain and swelling, especially with prolonged standing and heavy lifting. He was subsequently admitted for planned treatment with percutaneous embolization of the gonadal veins and associated collaterals. Venography following transjugular access demonstrated reflux into the left and right gonadal veins with extensive retroperitoneal collateralization to both the left and right gonadal veins (Figure 1A and B). Occlusion of the gonadal veins bilaterally was carried out at multiple levels, starting at the inguinal ring, using fibered coils (Tornado; Cook Inc., Bloomington, IN) in the gonadal veins and N-butyl cyanoacrylate (NBCA) glue to occlude the collateral branches.

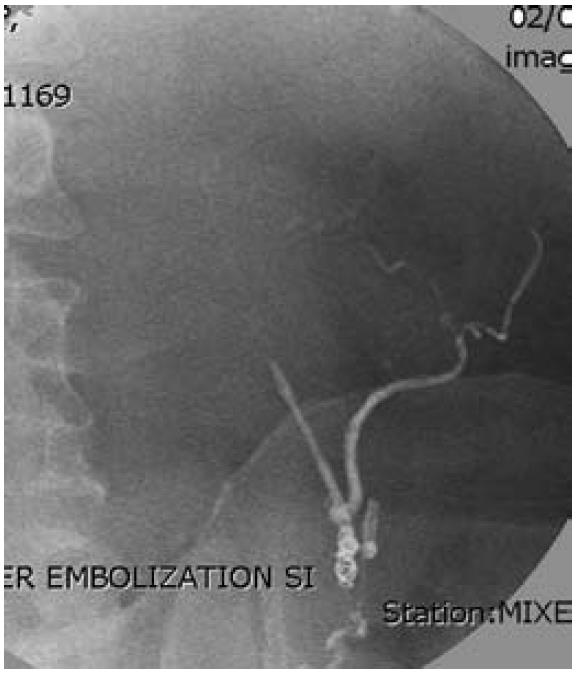

While the patient experienced initial improvement, 7 mo following treatment, his symptoms of testicular pain and swelling recurred. Repeat venography of the gonadal veins was performed to determine the etiology of the recurrence. Repeat access through the right internal jugular vein and catheterization of both renal veins showed no evidence of residual reflux into either gonadal vein (Figure 2). The right gonadal vein was occluded at its origin. Catheterization of the right renal capsular vein did not show evidence of filling of the gonadal system. Scrotal ultrasound performed on the same day revealed large bilateral varicoceles.

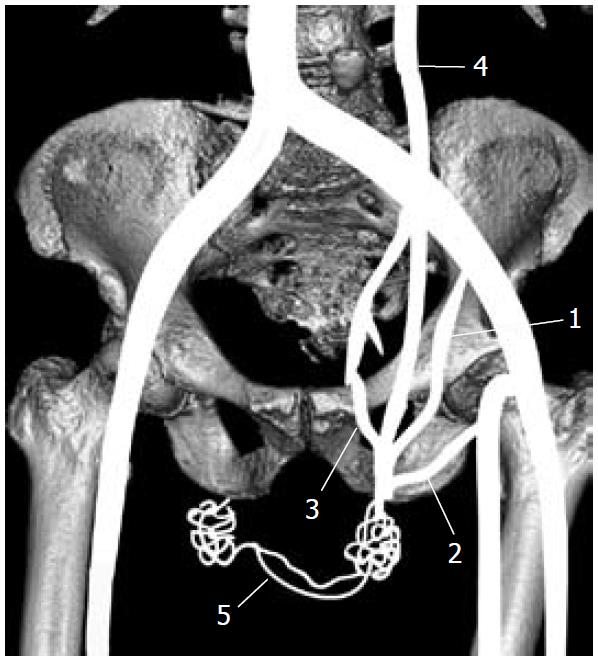

The patient was subsequently rescheduled for venography using direct puncture of the dilated pampiniform plexus. Under ultrasound guidance, a dilated branch of the right pampiniform plexus was accessed using a micropuncture needle, followed by placement of a 0.018-inch guidewire and a 3 French inner micropuncture catheter (Arrow International, Reading, PA) over the wire. Hand injection of contrast initially revealed filling of the varicocele followed by filling of the right saphenous vein, right femoral vein, left pampiniform plexus and left saphenous vein (Figure 3A and B). When the etiology of recurrent varicocele was established, treatment with sclerotherapy was not considered because of the likelihood of sclerosant reflux into the femoral and iliac venous systems. Following the diagnosis of recurrent varicocele, the patient proceeded to undergo surgical ligation of bilateral gonadal veins and unfortunately suffered a cardiac arrest shortly after the procedure.

A varicocele is an abnormal dilatation of the pampiniform plexus, the venous drainage system of the testicle. Primary varicoceles typically form as a result of valvular insufficiency of the gonadal vein, with concomitant enlargement of the pampiniform plexus. Secondary varicoceles may form as a manifestation of various disease processes, such as cirrhosis, abdominal neoplasms, portal hypertension, or heart failure[4]. Varicoceles can present with scrotal discomfort, or alternatively low semen counts and abnormal sperm motility as a treatable cause of male infertility[1,2,5,6].

The pampiniform plexus is a network of veins arising from the testicular venous outflow. It begins in the scrotum and extends into the spermatic cord, then coalesces to form the gonadal vein, which travels through the inguinal canal and into the retroperitoneum[1]. On the left, the gonadal vein usually drains into the left renal vein. On the right, it most often drains directly into the infrarenal inferior vena cava. Multiple collateral vein variations may arise, usually between the gonadal vein origin and the deep inguinal ring[2]. These are parallel or perpendicular to the gonadal vein, and may include retroperitoneal, perirenal, and lumbar veins.

Both surgical and percutaneous routes have provided effective treatment with reported recurrence rates up to 20%[1-3]. The reason for recurrence, most frequently demonstrated by retrograde gonadal venography, is collateralization of the gonadal vein by retroperitoneal collateral flow. Controversy exists as to the indications for treatment of varicocele, as well as the methods, which include a variety of surgical techniques, involving ligation of the gonadal vein, or percutaneous embolization with coil occlusion with or without venous sclerosis[1,5,7,8].

Initial evaluation of a varicocele usually begins with a physical examination, where scrotal palpation is performed with the patient relaxed and during a Valsalva maneuver[1]. Color Doppler ultrasound is widely accepted for the diagnosis and quantification of varicoceles. Several studies have reported this to have a better diagnostic accuracy than physical examination, with the most widely accepted criteria for diagnosis being the presence of multiple veins greater than 3.0-3.5 mm in diameter with reversal of flow on Valsalva[6].

Spermatic venography is the “gold standard” for diagnosis but is primarily employed during intended treatment of varicocele, be it surgical or percutaneous[6,9-12]. Reflux that lasts at least two seconds has been reported as equivalent to a positive venography result[1].

The goal of treatment of varicocele is interruption of retrograde flow into the pampiniform plexus from the gonadal and pre-existing collateral veins. Reported methods for percutaneous endovascular treatment include occlusion of the gonadal vein with coils[13], starting from just above the inguinal ligament, extending to the confluence of the gonadal vein with the renal vein, accompanied by treatment of collaterals with any number of liquid agents, including alcohol, polidocanol[2,5,14], sodium tetradecyl sulfate[8,15], and NBCA glue[16].

Treatment of recurrent varicocele begins with spermatic vein venography through catheterization of gonadal vein remnants or retroperitoneal collaterals from either the renal veins or retroperitoneal branches. Following surgical ligation, the proximal gonadal veins are most often patent, which facilitates venography[7,17]. Failure to demonstrate the gonadal vein or significant collateral circulation to the pelvic gonadal veins presents a dilemma with respect to diagnosing the cause of recurrence as well as to its treatment.

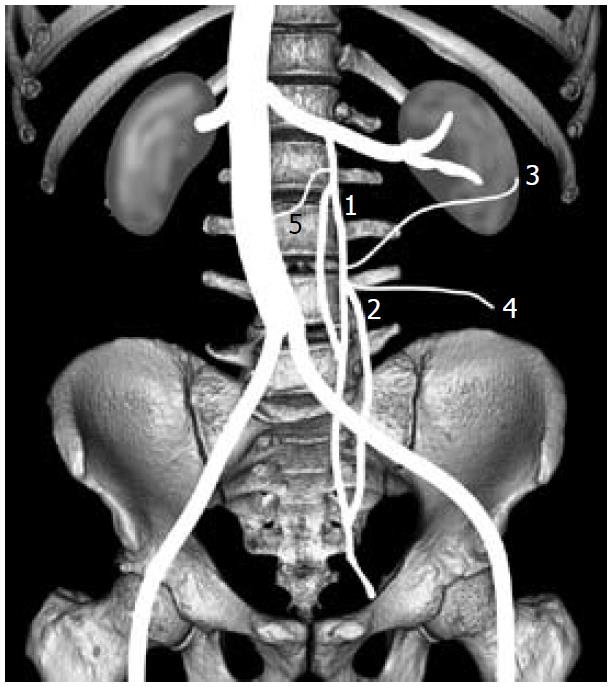

There have been many reviews of the anatomy of the gonadal vein and its collateral supply. In the simplest case, the pampiniform plexus of veins drains into a single gonadal vein, which empties into the renal vein on the left and directly into the inferior vena cava on the right. This corresponds with the type 1 anatomy of Bahren[2]. Parallel collaterals to the gonadal veins can occur at high, mid or low locations and correspond to type 2 Bahren or type P (subtypes A, B, and C) of Murray[2]. Additional collateral supply to the gonadal vein can occur from medial retroperitoneal branches, which may communicate with the contralateral gonadal vein, or from lateral retroperitoneal branches, which may communicate with colonic, distal renal, or renal capsular veins[18] (Figure 4). While these constitute the most significant collateralization to the gonadal veins and the most common causes of treatment failure, other collaterals exist and assume importance especially after endovascular occlusion or ligation of the gonadal vein.

Venography following surgical cannulation of a vein of the pampiniform plexus has been well described in the urology literature[9-12,17,18], but is infrequently referred to in the radiology literature. In addition, there is little mention of the anatomy that is appreciated through venography by this route. Access to the pampiniform plexus is achieved through trans-scrotal cut-down and cannulation of a vein of the plexus[3,9,10]. Using this route, collateralization of the pampiniform plexus is appreciated from the external pudendal vein via the saphenofemoral route[12,17]. Additional collaterals of a smaller magnitude have been shown, including the cremasteric vein (external spermatic vein), draining into the inferior epigastric vein at its origin from the external iliac vein, as well as the vein of the vas deferens, which ends in branches of the internal iliac vein[12,17]. Moreover, there is trans-scrotal collateralization of the right and left pampiniform plexus through scrotal veins[11,17] (Figure 5). This venous anatomy plays a role in recurrent varicocele in a minority of instances.

Of note is a classification of the etiology of varicocele based on differentiating a distal vs proximal nutcracker phenomenon[11,19]. The proximal or high nutcracker type, otherwise known as type I or anterior varicocele in the reviewed literature, is due to aorto-mesenteric compression of the left renal vein, causing renal-spermatic venous reflux. The distal or low nutcracker type, otherwise called type II or posterior varicocele, is caused by compression of the left common iliac vein by the left common iliac artery, leading to reflux into the deferential and cremasteric venous branches. A third type has also been identified, which is a combination of types I and II and may be accompanied by venous hypertension, as was the etiology in the case presented here.

Most recurrent varicoceles occur as a result of failure to eliminate collateral supply to the gonadal vein in the abdomen or pelvis. Recurrence from saphenofemoral collateral circulation or from internal iliac venous communication with the pampiniform plexus requires both ileo-femoral or saphenofemoral venous hypertension as well as retrograde flow in the affected veins. In the case under discussion, successful occlusion of the left and right gonadal veins to the level of and into the inguinal canal, along with cyanoacrylate occlusion of collateral veins, eliminated reflux from the gonadal venous system as a cause of recurrent varicocele. However, long-standing and recurrent systemic venous hypertension from severe cardiomyopathy combined with saphenous vein incompetency provided a route for collateralization of the pampiniform plexus and recurrent varicocele. Further steps to treat this patient’s recurrent varicocele via percutaneous methods were not undertaken, when considering the possibility of sclerosant reflux into the saphenofemoral and iliac venous systems.

As described above, percutaneous puncture of a dilated pampiniform plexus vein under ultrasound guidance was achieved using a micropuncture needle, a 0.018-inch guidewire, followed by placement of the inner 3-French catheter of the micropuncture system. Indeed, the procedure was no more complex than that used for venous access for peripherally inserted central catheter line placement. Therefore, this method should be considered for cases in which access to the gonadal venous system is not possible by traditional routes, or in which the cause of recurrent varicocele is not evident. This route can also be considered for antegrade sclerotherapy.

The outcome of this case cannot be applied to the large majority of varicocele diagnoses, most of which are a result of valve incompetence rather than a sequela of other disease processes. It does, however, underline the distinct venous anatomy of the testicle and presents a novel method of approaching scrotal venography via direct puncture of the pampiniform plexus using ultrasound guidance and a micropuncture system.

Peer reviewer: Tilo Niemann, MD, Department of Radiology, University Hospital Basel, Petersgraben 4, CH-4031 Basel, Switzerland.

S- Editor Cheng JX L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Bittles MA, Hoffer EK. Gonadal vein embolization: treatment of varicocele and pelvic congestion syndrome. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2008;25:261-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sze DY, Kao JS, Frisoli JK, McCallum SW, Kennedy WA, Razavi MK. Persistent and recurrent postsurgical varicoceles: venographic anatomy and treatment with N-butyl cyanoacrylate embolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19:539-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Niedzielski J, Paduch DA. Recurrence of varicocele after high retroperitoneal repair: implications of intraoperative venography. J Urol. 2001;165:937-940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bhosale PR, Patnana M, Viswanathan C, Szklaruk J. The inguinal canal: anatomy and imaging features of common and uncommon masses. Radiographics. 2008;28:819-35; quiz 913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Flacke S, Schuster M, Kovacs A, von Falkenhausen M, Strunk HM, Haidl G, Schild HH. Embolization of varicocles: pretreatment sperm motility predicts later pregnancy in partners of infertile men. Radiology. 2008;248:540-549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lee J, Binsaleh S, Lo K, Jarvi K. Varicoceles: the diagnostic dilemma. J Androl. 2008;29:143-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Paduch DA, Skoog SJ. Current management of adolescent varicocele. Rev Urol. 2001;3:120-133. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Reiner E, Pollak JS, Henderson KJ, Weiss RM, White RI. Initial experience with 3% sodium tetradecyl sulfate foam and fibered coils for management of adolescent varicocele. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19:207-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mottrie AM, Matani Y, Baert J, Voges GE, Hohenfellner R. Antegrade scrotal sclerotherapy for the treatment of varicocele in childhood and adolescence. Br J Urol. 1995;76:21-24. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Ficarra V, Porcaro AB, Righetti R, Cerruto MA, Pilloni S, Cavalleri S, Malossini G, Artibani W. Antegrade scrotal sclerotherapy in the treatment of varicocele: a prospective study. BJU Int. 2002;89:264-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Coolsaet BL. The varicocele syndrome: venography determining the optimal level for surgical management. J Urol. 1980;124:833-839. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Wishahi MM. Anatomy of the spermatic venous plexus (pampiniform plexus) in men with and without varicocele: intraoperative venographic study. J Urol. 1992;147:1285-1289. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Shlansky-Goldberg RD, VanArsdalen KN, Rutter CM, Soulen MC, Haskal ZJ, Baum RA, Redd DC, Cope C, Pentecost MJ. Percutaneous varicocele embolization versus surgical ligation for the treatment of infertility: changes in seminal parameters and pregnancy outcomes. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1997;8:759-767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gazzera C, Rampado O, Savio L, Di Bisceglie C, Manieri C, Gandini G. Radiological treatment of male varicocele: technical, clinical, seminal and dosimetric aspects. Radiol Med. 2006;111:449-458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gandini R, Konda D, Reale CA, Pampana E, Maresca L, Spinelli A, Stefanini M, Simonetti G. Male varicocele: transcatheter foam sclerotherapy with sodium tetradecyl sulfate--outcome in 244 patients. Radiology. 2008;246:612-618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Pollak JS, White RI. The use of cyanoacrylate adhesives in peripheral embolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2001;12:907-913. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hill JT, Hirsh AV, Pryor JP, Kellett MJ. Changes in the appearance of venography after ligation of a varicocele. J Anat. 1982;135:47-52. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Wishahi MM. Detailed anatomy of the internal spermatic vein and the ovarian vein. Human cadaver study and operative spermatic venography: clinical aspects. J Urol. 1991;145:780-784. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Nania G, Bronzetti B, Galletta E, Cucinotta A, Lucibello L, Panunzio P, Galeano A, Cocuzza G, Giordano T, Melina D. Percutaneous sclerotherapy for varicocele: a report of 300 cases. Osp Ital Chir. 2003;9:501-505. |