Published online Apr 28, 2022. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v14.i4.91

Peer-review started: December 29, 2021

First decision: February 21, 2022

Revised: March 13, 2022

Accepted: April 9, 2022

Article in press: April 9, 2022

Published online: April 28, 2022

Processing time: 116 Days and 10.5 Hours

The resulting tissue hypoxia and increased inflammation secondary to severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) combined with viral load, and other baseline risk factors contribute to an increased risk of severe sepsis or co-existed septic condition exaggeration.

To describe the clinical, radiological, and laboratory characteristics of a small cohort of patients infected by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 who underwent percutaneous drainage for septic complications and their post-procedural outcomes.

This retrospective study consisted of 11 patients who were confirmed to have COVID-19 by RT-PCR test and required drain placement for septic complications. The mean age ± SD of the patients was 48.5 ± 14 years (range 30-72 years). Three patients underwent cholecystostomy for acute acalculous cholecystitis. Percutaneous drainage was performed in seven patients; two peripancreatic collections; two infected leaks after hepatic resection; one recurrent hepatic abscess, one psoas abscess and one lumbar abscess. One patient underwent a percutaneous nephrostomy for acute pyelonephritis.

Technical success was achieved in 100% of patients, while clinical success was achieved in 4 out of 11 patients (36.3%). Six patients (54.5%) died despite proper percutaneous drainage and adequate antibiotic coverage. One patient (9%) needed operative intervention. Two patients (18.2%) had two drainage procedures to drain multiple fluid collections. Two patients (18.2%) had repeat drainage procedures due to recurrent fluid collections. The average volume of the drained fluid immediately after tube insertion was 85 mL. Follow-up scans show a reduction of the retained content and associated inflammatory changes after tube insertion in all patients. There was no significant statistical difference (P = 0.6 and 0.4) between the mean of WBCs and neutrophils count before drainage and seven days after drainage. The lymphocyte count shows significant increased seven days after drainage (P = 0.03).

In this study, patients having septic complications associated with COVID-19 showed relatively poor clinical outcomes despite technically successful percutaneous drainage.

Core Tip: This article highlights the relationship between coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and sepsis. COVID-19 is associated with high risk of severe sepsis or exaggeration of co-existed septic condition. Percutaneous drainage of septic complications co-existed with COVID-19 associated with relatively poor clinical outcomes despite technically successful procedures.

- Citation: Deif MA, Mounir AM, Abo-Hedibah SA, Abdel Khalek AM, Elmokadem AH. Outcome of percutaneous drainage for septic complications coexisted with COVID-19. World J Radiol 2022; 14(4): 91-103

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8470/full/v14/i4/91.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4329/wjr.v14.i4.91

Sepsis is defined as a life-threatening organ dysfunction that happens due to dysregulated host response to an infection[1]. In the bacterial type of sepsis, which is the most frequent etiology, early and rapid therapy by the appropriate antibiotic is essential to reduce the incidence of complications and mortality rates. Most patients infected by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) present no severe symptomatology, but almost 5% of patients show severe lung injury or even multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, with mortality at the ICUs between 8% and 38% depending on the country[2,3]. Patients admitted to ICU showed a dysregulated host response in the form of hyperinflammation, changes in the coagulation profile, and dysregulation in the immune response[4], similar to what happens in bacterial sepsis[5,6]. The body’s adaptive protection mechanism is formed by a moderate inflammatory response and immune suppression, and if any of them become excessive or uncontrolled, this protective compensation will transform into destructive and decompensated status, then sepsis develops[7-9]. Accordingly, most deaths in critically ill coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients are caused by sepsis[10,11].

Hematological examinations for COVID-19 patients show elevated cytokines, C-reactive protein (CRP), abnormal liver and myocardial enzymes decreased lymphocytes, declined platelets, and increased D-dimmer[12]. These findings are similar to sepsis caused by bacterial infections. So, severe COVID-19 could be a sepsis-induced by viral infection causing severe systemic inflammatory response (so-called inflammatory storm)[13,14]. Inflammatory storms are not unique to COVID-19 but also happen in other respiratory viral infections that mimic COVID-19[15,16], such as influenza, SARS, avian influenza, swine flu, and MERS[17-19]. Additionally, specimen cultures in about 80% of COVID-19 patients with septic complications show no bacterial or fungal infection, and the viral infection seems to be the only cause for sepsis[20,21]. Accordingly, sepsis is expected to be responsible for worsening the clinical conditions of these critically ill COVID-19 patients. Our objective was to describe the clinical, radiological, and laboratory characteristics of a small cohort of patients infected by SARS-CoV-2 who underwent percutaneous drainage and their post-procedural outcomes. We hypothesized that septic complication associated with severe COVID-19 has a poor outcome despite adequate percutaneous drainage and antibiotic therapy.

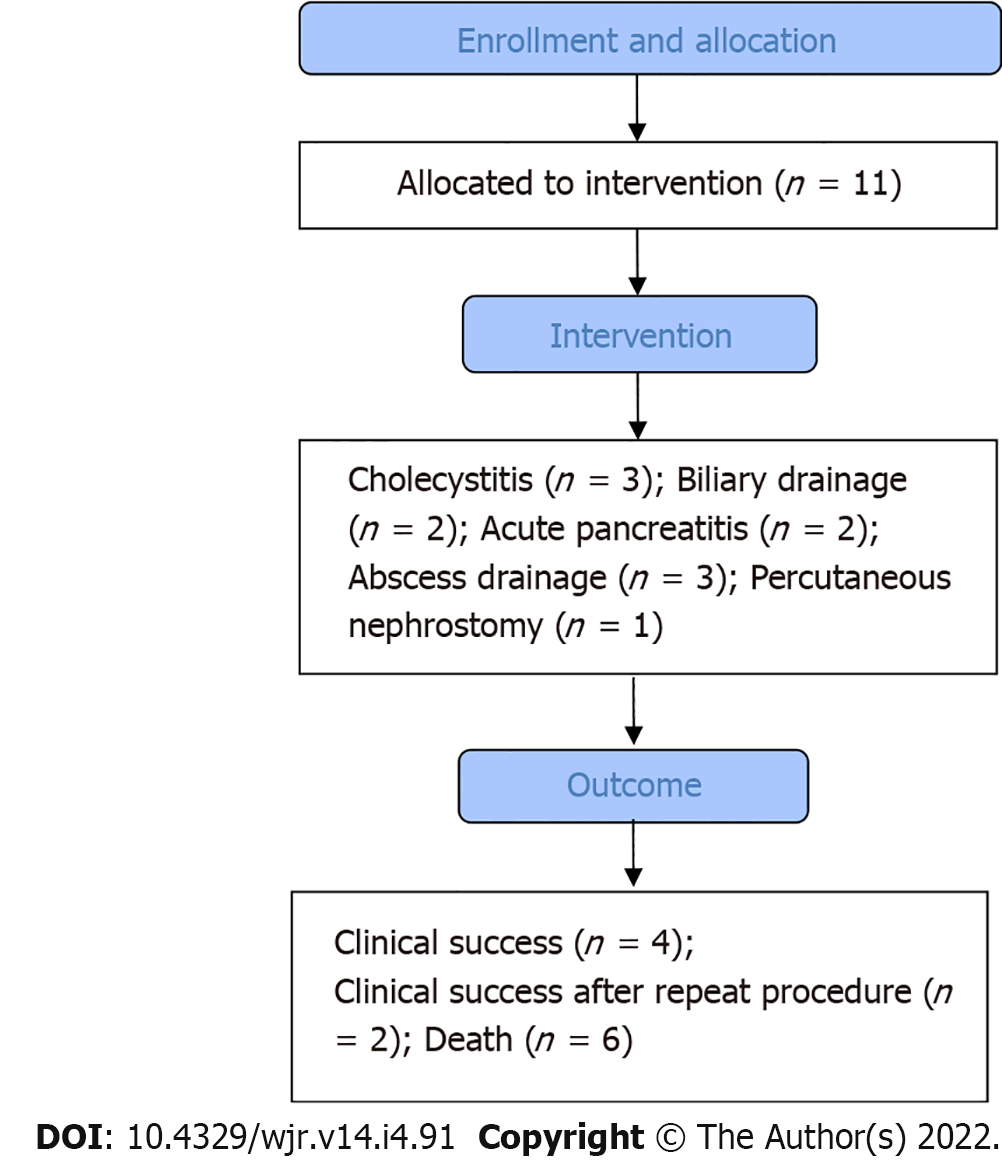

A local institutional review board approved this retrospective study, and waivers of consent of medical record review were received. COVID-19 patients who underwent image-guided percutaneous drainage for suspected septic complications were identified. Patient demographics and clinical and radiological reports were obtained through electronic medical records and picture archiving and communication system (PACS). The severity of the pulmonary parenchymal involvement and distribution of the pulmonary lesions secondary to COVID-19 was assessed by chest X-ray in 4 patients and chest CT in 7 patients. Flow chart of the study is shown in Figure 1.

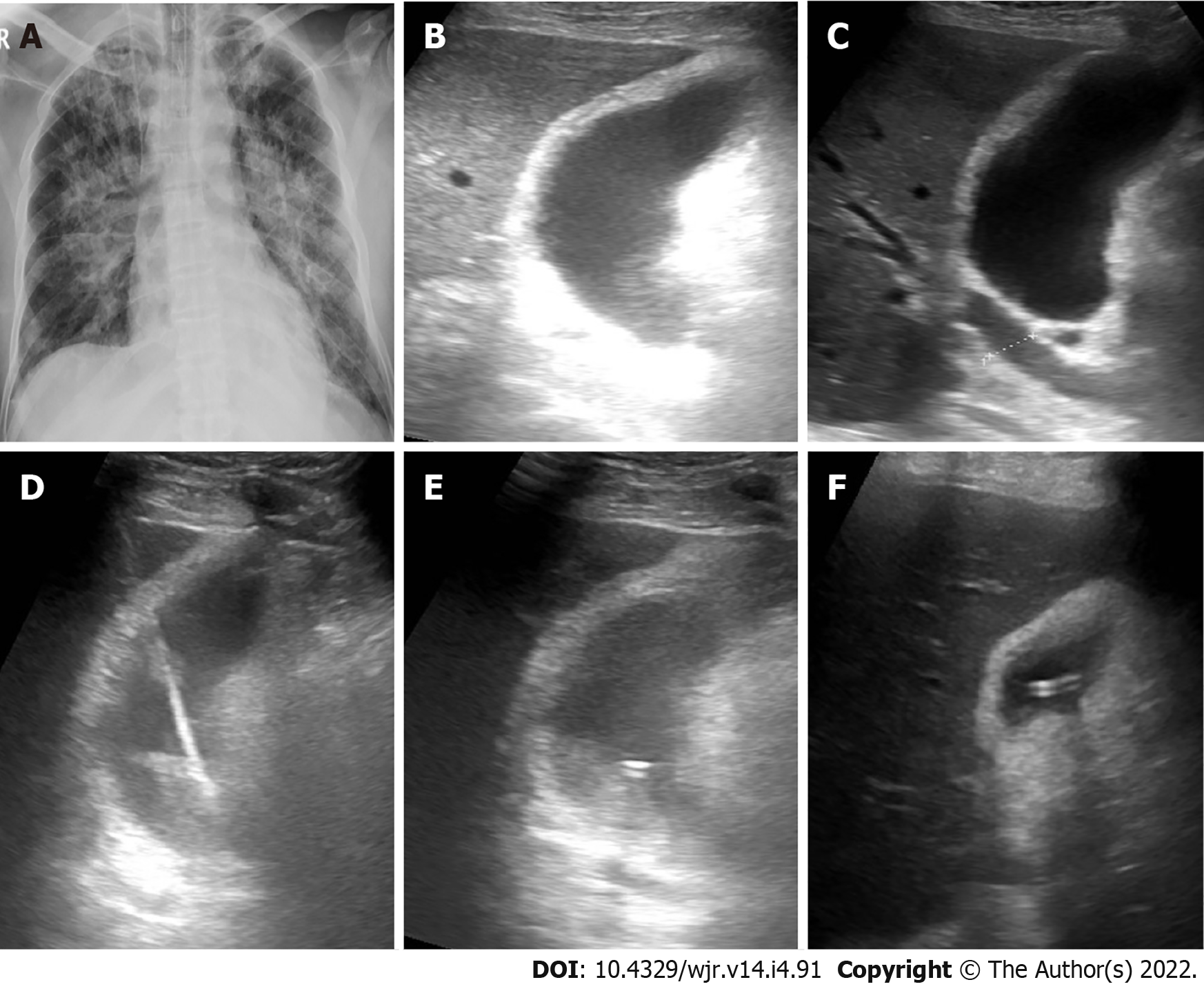

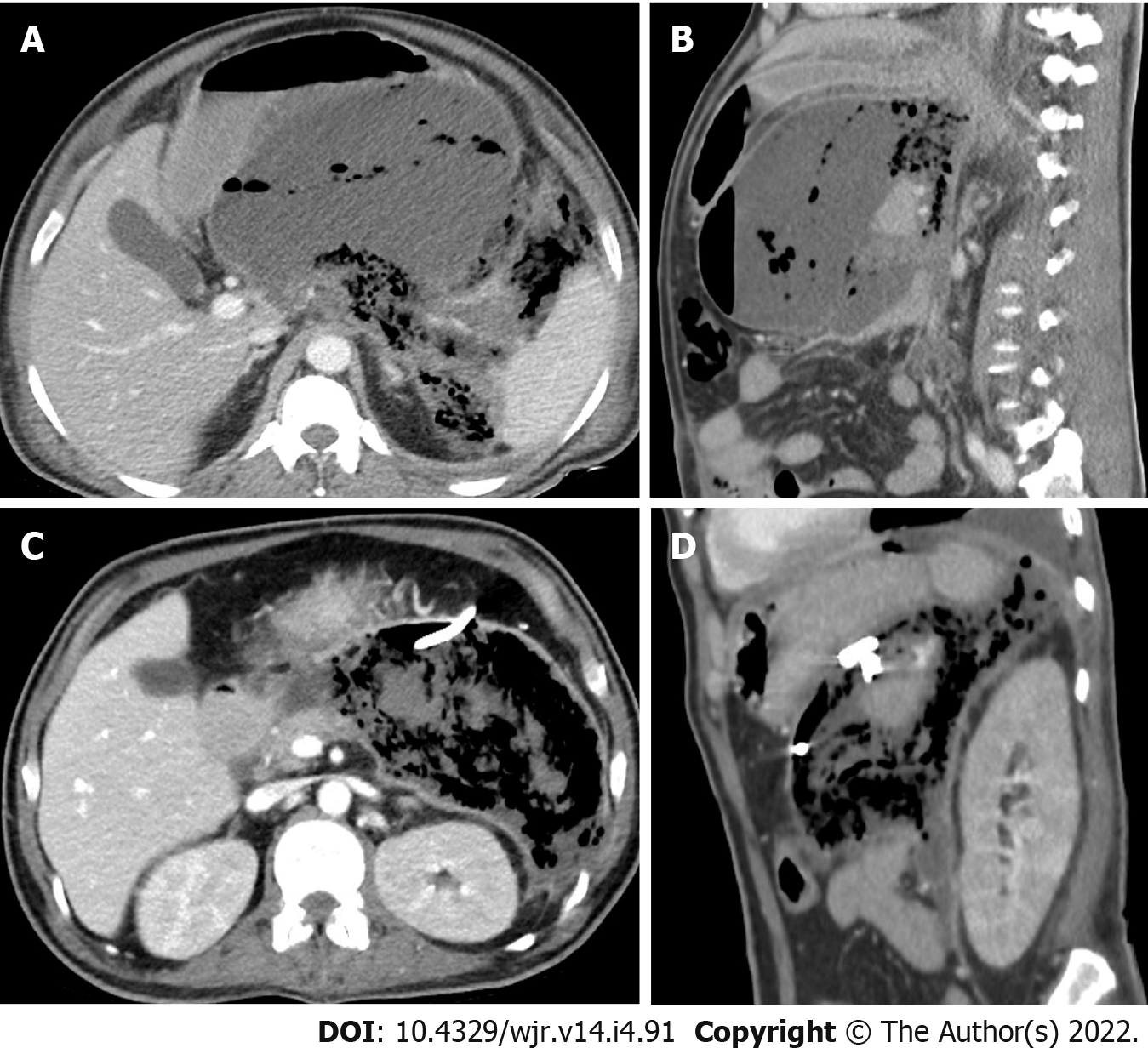

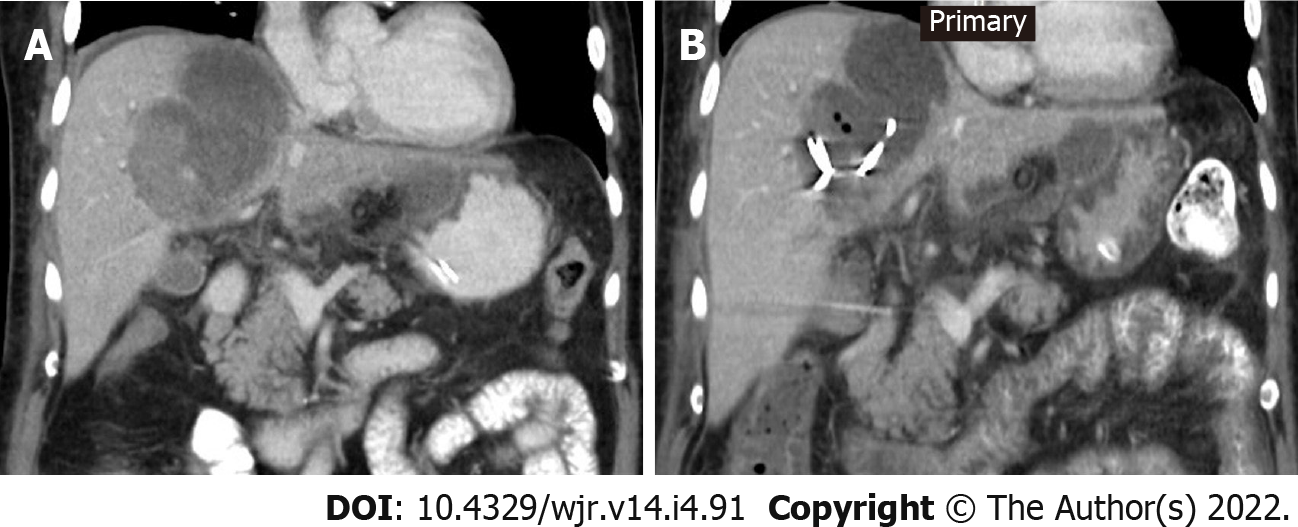

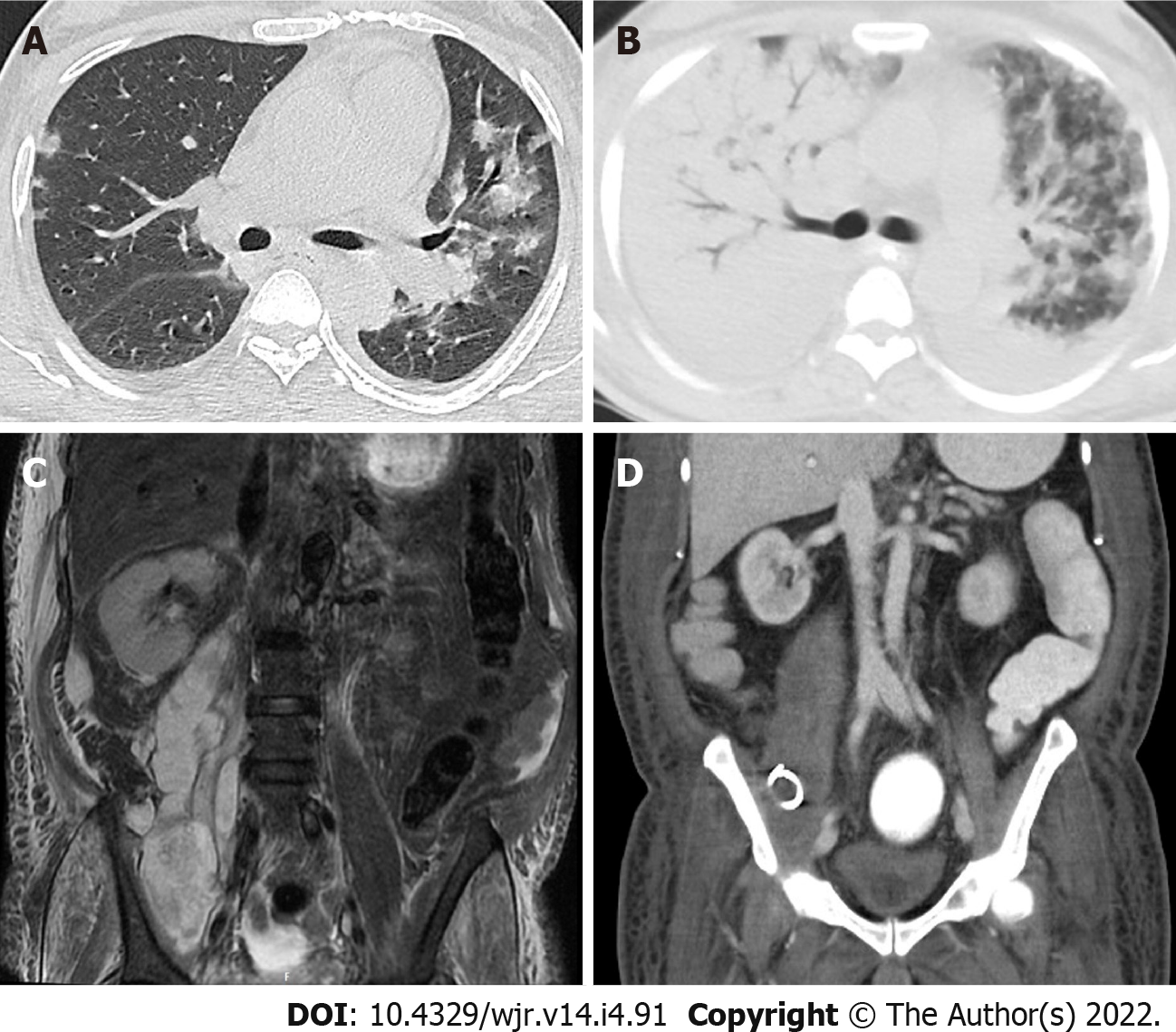

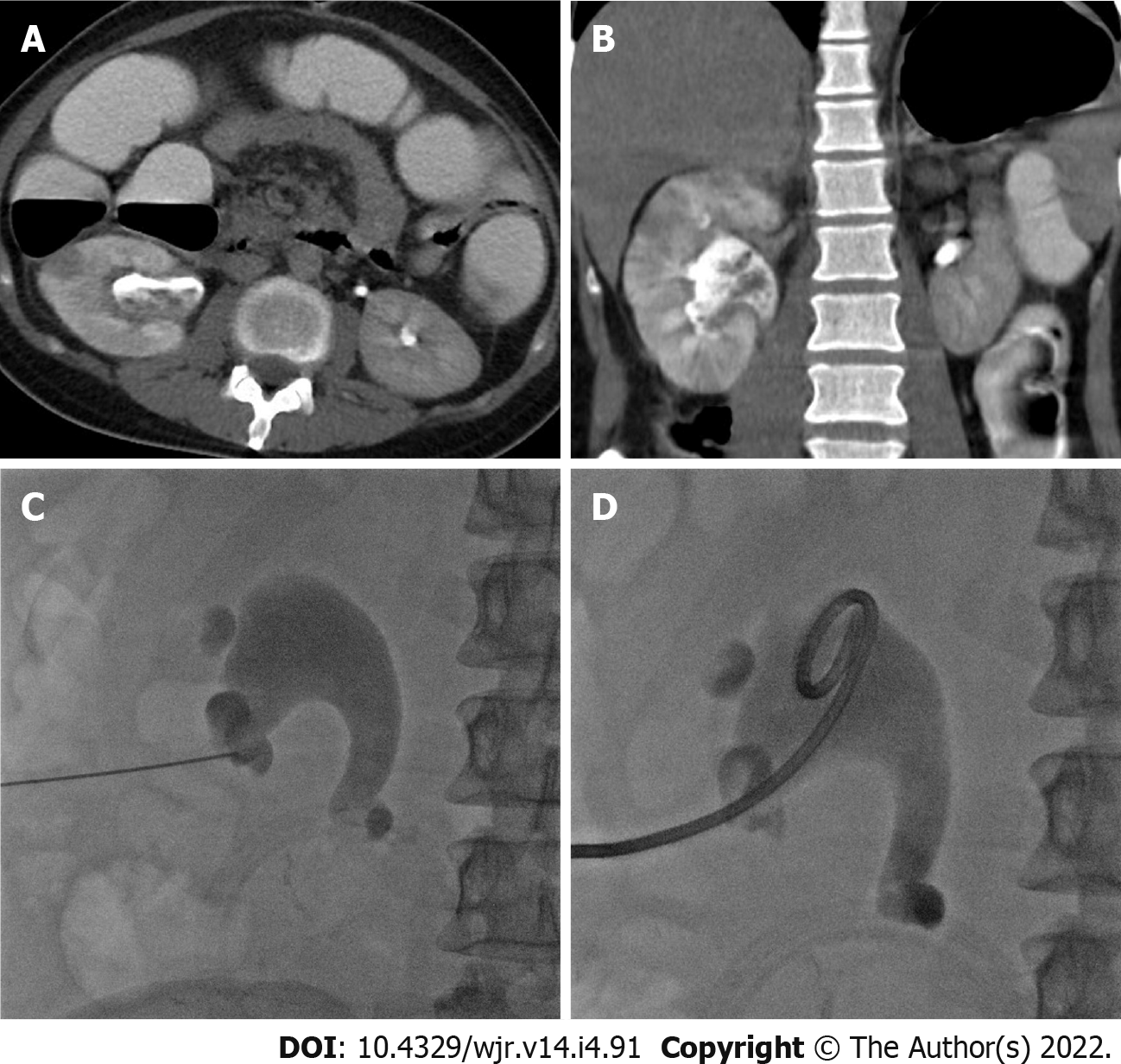

Eleven patients (10 males and 1 female) who were confirmed to have COVID-19 by RT-PCR test required drain placement for septic complications. The mean age ± SD of the patients was 48.5 ± 14 years (range 30-72 years). Three patients underwent cholecystostomy for acute acalculous cholecystitis (Figure 2). Percutaneous drainage was performed in seven patients; two peripancreatic collections (Figure 3); two infected bile leaks in hepatic donor and after resection of hepatic hemangioma; one recurrent hepatic abscess after eight days of surgical evacuation (Figure 4), one psoas abscess (Figure 5) and one lumbar abscess. One patient underwent percutaneous nephrostomy for acute pyelonephritis (Figure 6).

The primary outcome measures were technical and clinical success. The technical success was achieved by completion of the procedure without procedural complications, while the definition of clinical success was the resolution of symptoms without the subsequent need for operative drainage or patient mortality secondary to related sepsis. Secondary outcomes included the amount of drained fluid, microbial analysis of drained fluid, the period of tube drainage, and changes in laboratory findings before and after drainage.

Septic complications were diagnosed by ultrasonography, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging. Two interventional radiologists at two institutions with 10 and 13 years of experience performed all percutaneous drainage procedures. All procedures were done after administration of local anesthesia. Percutaneous access into the collections, inflamed gall bladder, or kidney was achieved under sonographic guidance with an 18- or 21-gauge needle. Using the Seldinger technique and micro-puncture set, following serial dilatations, a drainage catheter was placed. The drainage catheters used ranged from 8-French to 10-French. In all cases, no immediate complications were noted.

Antibiotic therapy was started once the symptoms of septic complications presented on the patients. The antibiotics regimen was readjusted according to the drained fluid culture results. The drained fluid for each patient was analyzed regarding its character and maximum possible volume when the tubes were initially placed. Then a fluid sample was sent for bacterial culture and gram stain evaluation. Patients were observed for any major complications requiring surgical intervention till the last date of follow-up.

Data were analyzed with SPSS® V. 21 (IBM Corp., New York, NY, United States; formerly SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). The normality of data was first tested with the Shapiro test. Qualitative data were described using numbers and percentages. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± SD for parametric data and median (range) for non-parametric data. Finally, the laboratory findings were compared with Wilcoxon test.

Fever and abdominal pain were the most common presenting symptoms, and acute kidney injury (AKI) was the most frequent comorbidity. Technical success was achieved in 100% of patients, while clinical success was achieved only in 4 of 11 patients (36.4%). Despite percutaneous drainage, one patient (9%) needed exploratory laparotomy five days after drainage that revealed perforated sigmoid colon, which was managed by resection followed by patient improvement and discharge after 18 d. Six other patients (54.5%) died within a month after proper percutaneous drainage and adequate antibiotic coverage, all of them were admitted to ICU and put under mechanical ventilation. The cause of death was overlapped between COVID-19 related respiratory failure and sepsis. One patient needed cystogasterostomy for peripancreatic collection after 21 d of tube insertion. Two patients (18.2%) had two drainage procedures to drain multiple fluid collections. Two patients (18.2%) had recurrent fluid collections and repeated percutaneous drainage procedures. The average volume of the drained fluid immediately after tube insertion was 85 mL. The average duration of drainage was 16 d. Follow-up scans showed a reduction of the retained content and associated inflammatory changes after tube insertion in all patients. Patient demographics, comorbidities, and outcomes are listed in Table 1.

| Cause of sepsis | Procedures | Age (yr) | Sex | Presentation | Co-morbidities | Ventilator | Tracheostomy | Outcome | |

| Patient 1 | Acute cholecystitis | Cholecystostomy | 72 | Male | Fever | IHD. AKI | 40 d before drain | 20 d before drain | Died 8 d post drain |

| Patient 2 | Cholangitis and cholecystitis | Cholecystostomy | 61 | Male | Fever | Jaundice. AKI (on dialysis) | 1 d before drain | 12 d post drain | Died 16 d post drain |

| Patient 3 | Acute cholecystitis | Cholecystostomy | 55 | Male | Abdominal pain | DM | No | No | Discharged 4 d post drain. |

| Patient 4 | Post-operative biliary leakage resection of hemangioma | U/S guided drain | 48 | Female | Fever | DM. Septic shock | 10 d post drain | No | Died 12 d post drain |

| Patient 5 | Post-operative biliary leakage after liver resection for transplant | U/S guided drain | 30 | Male | Fever | No | No | No | Discharged 18 d post drain |

| Patient 6 | Acute pancreatitis | CT-guided drain and EUS cystogastrostomy | 43 | Male | Abdominal pain | HTN. Hyperlipidemia | 27 d post drain | No | Died 28 d post drain |

| Patient 7 | Acute pancreatitis | U/S guided drain | 41 | Male | Abdominal pain | GB stones. Biliary obst. AKI | No | No | Discharged 10 d post drain |

| Patient 8 | Recurrent hepatic abscess after surgical evacuation | U/S guided drain (2 tubes) | 63 | Male | Abdominal pain | DM. AKI | 1 d before drain | 1 d before drain | Died 19 d post drain |

| Patient 9 | Right ilio-psoas and perivetebral abscesses | CT-guided drain then tube upsizing | 60 | Male | Abdominal pain | HTN. DM, AKI | 3 d before drain | 7 d post drain | Died 13 d post drain |

| Patient 10 | Left lumbar region abscess and unhealthy sigmoid colon | CT-guided drainage. Sigmoid resection | 31 | Male | Abdominal pain and distension | Crohn’s disease. Achalasia. GJ. Esophageal dilatation | No | No | Clinical failure after 18 d followed by another tube insertion and sigmoid resection. Discharged 48 d |

| Patient 11 | Right pyelonephritis | Rt PCN | 30 | Male | Abdominal pain | Right hemicolectomy | No | No | Discharged 9 d post drain. Recurrence after 39 d and managed by tube exchange |

The nature of drained fluid was reported in all cases. The fluid was reported as “dark green” or “pus” in cholecystostomy cases, “serosanguinous” and “infected bile” in complicated hepatic resection cases, “brownish” in the peripancreatic collection, “clotted blood” in the hepatic abscess, and “pus” in the other collections. After all procedures, samples from drained fluid samples were sent for microbial analysis. Peripheral blood culture was performed for 9 out of 11 patients. In three cases (27.3%), fluid culture results were negative for bacterial growth; however, in one of them, the peripheral blood culture was positive for Klebsiella pneumonia. Eight cases (72.7%) were found to have positive fluid culture, with Escherichia coli being the most common isolated pathogen followed by Klebsiella pneumonia.

Only three patients had imaging features of severe pulmonary parenchymal disease attributed to COVID-19 at drainage tome, nevertheless three other patients were admitted to ICU and put under ventilator due to progression of respiratory symptoms. The parenchymal lesions were ground-glass opacities and consolidations with the basal and peripheral predominant distribution. In addition, pleural effusion was reported in three patients. The median time between confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 by RT-PCR test and drainage of septic complications (time to drainage) was 8 d (range 0 d to 48 d). Table 2 shows data of drainage procedure, drained fluid, outcome, and chest imaging.

| IR procedure | Drain | Guide | Puncture | Drained fluid | Culture | Chest imaging | COVID-19 severity | Lesion distribution | Time between PCR test and drainage | ||

| Drain | Peripheral blood | ||||||||||

| Patient 1 | Cholecystostomy | 1 (8 Fr) | U/S | 18G needle | Dark green | -ve | MDR (Klebsiella) | X-ray | Severe | Bilateral consolidation | 48 d |

| Patient 2 | Cholecystostomy | 1 (8 Fr) | U/S | 18G needle | Dark green | E.coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae | -ve | CT | Mild | Bilateral basal GGO with minimal effusion | 3 d |

| Patient 3 | Cholecystostomy | 1 (8 Fr) | U/S | 18G needle | Pus | P. aeruginoa. MRSA. E.coli | -ve | X-ray | Normal | Normal | 5 d |

| Patient 4 | Percutaneous drainage | 1 (10 Fr) | U/S | 18G needle | Infected bile | E.coli | -ve | CT | Sever | Bilateral consolidation with mild effusion | 8 d |

| Patient 5 | Percutaneous drainage | 1 (8 Fr) | U/S | 18G needle | Sero-sanginous | -ve | -ve | CT | Mild | Mild right pleural effusion | 3 d |

| Patient 6 | Percutaneous drainage | 1 (10 Fr) | CT | 21G needle | Brownish | E.coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae | -ve | CT | Mild | Left minimal effusion and basal GGO | 17 d |

| Patient 7 | Percutaneous drainage | 1 (8 Fr) | CT | 18G needle | Brownish | E.coli | -ve | CT | Mild | Bilateral basal GGO | 2 d |

| Patient 8 | Percutaneous drainage | 2 (8 Fr) | U/S | 18G needle | Clotted blood | -ve | -ve | X-ray | Normal | Mild right side pleural effusion | 9 d |

| Patient 9 | Percutaneous drainage | 1 (10 Fr). 1 (8 Fr) | CT and US | 21G needle | Pus | MRSA and staph aureus | -ve | CT | Severe | Bilateral GGO and consolidations | 15 d |

| Patient 10 | Percutaneous drainage | 2 (8 Fr) | CT | 21G needle | Pus | E.coli and Ent. Foecalis | NA | CT | Mild | Right side GGO | 0 d |

| Patient 11 | Right PCN | 2 (8 Fr) | U/S and fluoro | 21G needle | Pus | Klebsiella pneumoniae | -ve | X-ray | Normal | Normal | 12 d |

The mean WBCs and neutrophil counts show reduction 1 d and 7 d after drainage however there was no significant statistical difference (P = 0.6) between the mean of WBCs count before drainage (15.4 × 109/L) and seven days after drainage (12.1 × 109/L) and between the mean count of neutrophil (P = 0.4) before drainage (82.8 × 109/L) and seven days after drainage (70.9 × 109/L). The lymphocyte count shows significant increased seven days after drainage (P = 0.03). Five patients had AKI manifested by elevation of the serum creatinine and urea levels. Total bilirubin level was elevated in eight patients and showed no significant reduction after drainage (P = 0.2). The CRP values were not significantly different (P = 0.06) before (182.0 mg/dL) and one week after tube insertion (133.0 mg/dL). Other inflammatory markers as D-dimer, procalcitonin and LDH were elevated in all patients before drainage and showed variable degree of non-statistically reduction and increase after drainage. The laboratory findings are listed in Table 3.

| Pre drain | D1 | D7 | P value | |

| WBCs × 109/L | 15.4 (12.50-17.40) | 18.8 (10.6-22.1) | 12.1 (10.3-21.8) | 0.656 |

| Neutrophil × 109/L | 82.8 (72.3-91.8) | 86.6 (70.4-94.2) | 70.9 (60.9-92.3) | 0.091 |

| Lymphocyte × 109/L | 6.8 (3.7-9.9) | 7.10 (2.8-11.2) | 10.9 (2.9-19.2) | 0.032a |

| CRP (mg/L) | 182.0 (91.0-368.0) | 166.0 (32.0-80.0) | 133.0 (26.0-170.0) | 0.061 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 122.0 (70.0-353.0) | 109.0 (54.0-426.0) | 97.0 (56.0-364.0) | 0.789 |

| Urea (mmol/L) | 9.2 (5.8-19.7) | 8.6 (3.6-22.4) | 9.1 (2.8-28.2) | 0.574 |

| Bilirubin (μmol/L) | 19.1 (15.0-28.4) | 14.4 (29.9-12.4) | 15.5 (12.5-21.8) | 0.247 |

| D-Dimer (ng/mL) | 1441.0 (620.0-3340.0) | 1363.0 (460.0-2780.0) | 1413.0 (380.0-3560.0) | 0.373 |

| Procalcitonin (ng/mL) | 1.5 (1.1-3.0) | 1.87 (0.85-3.56) | 1.5800 (0.31-3.11) | 0.398 |

| LDH (IU/L) | 359.0 (194.0-750.0) | 397.0 (155.0-768.0) | 438.0 (144.0-798.0) | 0.929 |

This study presents the clinical, radiological, and laboratory data for patients who underwent percutaneous drainage to manage septic complications associated with COVID-19 infection. The main finding is that patients with suspected septic complications associated with COVID-19 show relatively poor outcomes with 36.4% clinical success of percutaneous drainage despite 100% technical success. This finding was confirmed by the insignificant difference between the inflammatory markers before and after tube drainage insertion. Severe sepsis related to COVID-19 viral infection may be related to a decrease in mitochondrial efficiency and dysfunction of the respiratory chain[22,23]. In addition, autopsies have confirmed hyperinflammatory state with organ fibrosis, especially in high metabolic cells with high mitochondrial volume such as pneumocytes, endothelial cells, hepatocytes, and renal cells[24]. The resulting tissue hypoxia and increased inflammation, viral load, and other baseline risk factors contribute to an increased risk of severe sepsis or co-existed septic condition exaggeration.

This study included different types of septic complications as acute acalculous cholecystitis, acute pancreatitis, post-operative infection, abscesses in different locations, and acute pyelonephritis. Several reports described acute acalculous cholecystitis in COVID-19 patients[25-30] and raised the possibility of underlying dysregulated immune response or presence of viral RNA within the gall bladder wall as a culprit factor[28-30]. Percutaneous cholecystostomy for COVID-19 patients is recommended by multi-society position statement in case of surgical contraindication and after the failure of conservative therapy with antibiotics[31]. It is generally a preferred non-surgical procedure due to its relative safety, simplicity of execution, and reduced costs. Mattone et al[25] reported clinical failure of percutaneous cholecystostomy after 3-d from tube insertion; the patient was shifted to surgery that revealed gangrenous cholecystitis. In this study, clinical success was reported only in one of three patients had cholecystostomy drainage of acute cholecystitis. Contrary to this result, cholecystostomy improved the clinical status of patients presented by acute acalculous cholecystitis co-existed with COVID-19[26,27]; however, the period of hospitalization was prolonged (25-67 d) compared to the mean hospitalization period in non-COVID-19 patients (10.5 d)[32].

COVID-19 associated pancreatic injury and acute pancreatitis are thought to be a result of direct cytopathic effect mediated by local viral replication or indirect mechanism related to either a systemic response to a harmful immune response or respiratory failure induced by the SARS-CoV-2[33]. COVID-19 patients with acute pancreatitis are more likely to experience admission to the ICU, peripancreatic fluid collections, pancreatic necrosis, persistent organ failure, prolonged hospital stay, and higher than usually reported 30-d mortality[34]. We encountered two cases of pancreatitis in the current study, one of them died 28 days after drainage.

In a meta-analysis performed by Abate et al[35], twenty-three articles with 2947 participants were included. The meta-analysis showed a very high global rate of postoperative mortality among COVID-19 patients of 20%. Percutaneous drainage was performed for two patients after complicated hepatic resection for hemangioma and liver donor, only the second patient survived and was discharged 18 days after drainage. The good outcome in this patient is attributed to the non-inflammatory nature of the drained fluid, lower inflammatory marker and less severity of COVID-19 as compared to the other patient.

Hepatic abscesses have been described in association with COVID-19[36,37]. While García Virosta et al[36] reported clinically successful percutaneous drainage for hepatic abscess and patient discharge after ten days from tube insertion, Elliot et al[37] reported a rapidly progressive severe acute respiratory distress syndrome, which was complicated by multiorgan failure and severe sepsis that ended by death after percutaneous drainage of hepatic abscess in a patient with COVID-19. One patient in this study presented with a large lumbar region abscess secondary to sigmoid colon perforation as proved by laparotomy. Bowel perforation secondary to COVID-19 has been attributed to microcirculation thrombosis[38] or direct insult to the colonic cells by the SARS-CoV-2 itself[39].

There is scanty literature on the association between COVID-19 and acute pyelonephritis. van 't Hof et al[40] described an unusual course of acute pyelonephritis in a young female with persistent fever and multiple blood clotting and hemorrhagic events one week after recovery from COVID-19. Similar to our results, pyelonephritis was managed successfully by percutaneous nephrostomy. More frequently, AKI is encountered among critically ill patients with COVID-19, affecting approximately 20%-40% of patients admitted to the hospital and particularly to the ICU[41]. AKI was the most frequent comorbidity (5/11) in this study. A significantly higher in-hospital death rate for patients with kidney abnormalities and AKI was reported by a study consisting of 701 SARS-CoV-2 positive patients[42].

COVID-19 requires a multidisciplinary approach to treatment with interventional radiology procedures that have contributed to worldwide patient care. In a study consisting of 92 patients who underwent 124 interventional procedures[43] [abscess drainage (12), percutaneous cholecystostomy (8), and nephrostomy tube (4)], the mortality rate in this study was 16.3 % (15/92). However, there was no specific data as regards clinical, laboratory, and radiological data of the included patients or correlation between specific IR procedures and mortality. In this study the poor outcome was related to the combined burden of severe COVID-19 pneumonia, presence of other co-morbidities and extent of sepsis.

This study has several limitations. First, our study cohort is small. Second, this study was retrospective in nature. Third, our results were not compared to a negative SARS-CoV-2 group with matched age, complication, and comorbidities; this may have overestimated the poor outcome of percutaneous drainage in this study group.

The current study demonstrates relatively poor clinical outcomes for patients having suspected septic complications associated with COVID-19 despite technically successful tube drainage and adequate antibiotic therapy. This study emphasizes the need for a large-scale comparative study on the relationship between septic complications, COVID-19, and comorbidities that might lead to poor clinical outcomes and clarifies the necessary precautions for percutaneous drainage in such patients.

The resulting tissue hypoxia and increased inflammation secondary to severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) combined with viral load, and other baseline risk factors contribute to an increased risk of severe sepsis or co-existed septic condition exaggeration.

We performed percutaneous drainage for septic complications of COVID-19 and wanted to report our experience.

To describe the clinical, radiological, and laboratory characteristics of a small cohort of patients infected by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 who underwent percutaneous drainage for septic complications and their post-procedural outcomes.

This retrospective study consisted of 11 patients who were confirmed to have COVID-19 by RT-PCR test and required drain placement for septic complications. The mean age ± SD of the patients was 48.5 ± 14 years (range 30-72 years). Three patients underwent cholecystostomy for acute acalculous cholecystitis. Percutaneous drainage was performed in seven patients; two peripancreatic collections; two infected leaks after hepatic resection; one recurrent hepatic abscess, one psoas abscess and one lumbar abscess. One patient underwent a percutaneous nephrostomy for acute pyelonephritis.

Technical success was achieved in 100% of patients, while clinical success was achieved in 4 out of 11 patients (36.3%). Six patients (54.5%) died despite proper percutaneous drainage and adequate antibiotic coverage. One patient (9%) needed operative intervention. Two patients (18.2%) had two drainage procedures to drain multiple fluid collections. Two patients (18.2%) had repeat drainage procedures due to recurrent fluid collections. The average volume of the drained fluid immediately after tube insertion was 85 mL. Follow-up scans show a reduction of the retained content and associated inflammatory changes after tube insertion in all patients. There was no significant statistical difference (P = 0.6 and 0.4) between the mean of WBCs and neutrophils count before drainage and seven days after drainage. The lymphocyte count shows significant increased seven days after drainage (P = 0.03).

In this study, patients having septic complications associated with COVID-19 showed relatively poor clinical outcomes despite technically successful percutaneous drainage.

Prospective, larger multicentric study is needed to validate our results.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Radiology, nuclear medicine and medical imaging

Country/Territory of origin: Egypt

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Wang CY, Taiwan; Wang D, Thailand S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: A P-Editor: Gao CC

| 1. | Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, Bellomo R, Bernard GR, Chiche JD, Coopersmith CM, Hotchkiss RS, Levy MM, Marshall JC, Martin GS, Opal SM, Rubenfeld GD, van der Poll T, Vincent JL, Angus DC. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315:801-810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15803] [Cited by in RCA: 17221] [Article Influence: 1913.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 2. | Carter C, Notter J. COVID-19 disease: a critical care perspective. Clin Integr Care. 2020;1:100003. |

| 3. | Quah P, Li A, Phua J. Mortality rates of patients with COVID-19 in the intensive care unit: a systematic review of the emerging literature. Crit Care. 2020;24:285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 32.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, Sanchez E, Tattersall RS, Manson JJ; HLH Across Speciality Collaboration, UK. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020;395:1033-1034. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6366] [Cited by in RCA: 6752] [Article Influence: 1350.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ding R, Meng Y, Ma X. The Central Role of the Inflammatory Response in Understanding the Heterogeneity of Sepsis-3. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:5086516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Nedeva C, Menassa J, Puthalakath H. Sepsis: Inflammation Is a Necessary Evil. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2019;7:108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 223] [Article Influence: 37.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gentile LF, Cuenca AG, Efron PA, Ang D, Bihorac A, McKinley BA, Moldawer LL, Moore FA. Persistent inflammation and immunosuppression: a common syndrome and new horizon for surgical intensive care. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72:1491-1501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 569] [Cited by in RCA: 552] [Article Influence: 42.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rosenthal MD, Kamel AY, Rosenthal CM, Brakenridge S, Croft CA, Moore FA. Chronic Critical Illness: Application of What We Know. Nutr Clin Pract. 2018;33:39-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Liu Y, Mao B, Liang S, Yang JW, Lu HW, Chai YH, Wang L, Zhang L, Li QH, Zhao L, He Y, Gu XL, Ji XB, Li L, Jie ZJ, Li Q, Li XY, Lu HZ, Zhang WH, Song YL, Qu JM, Xu JF; Shanghai Clinical Treatment Experts Group for COVID-19. Association between age and clinical characteristics and outcomes of COVID-19. Eur Respir J. 2020;55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 258] [Article Influence: 51.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Thomas-Rüddel D, Winning J, Dickmann P, Ouart D, Kortgen A, Janssens U, Bauer M. [Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): update for anesthesiologists and intensivists March 2020]. Anaesthesist. 2020;69:225-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Alhazzani W, Møller MH, Arabi YM, Loeb M, Gong MN, Fan E, Oczkowski S, Levy MM, Derde L, Dzierba A, Du B, Aboodi M, Wunsch H, Cecconi M, Koh Y, Chertow DS, Maitland K, Alshamsi F, Belley-Cote E, Greco M, Laundy M, Morgan JS, Kesecioglu J, McGeer A, Mermel L, Mammen MJ, Alexander PE, Arrington A, Centofanti JE, Citerio G, Baw B, Memish ZA, Hammond N, Hayden FG, Evans L, Rhodes A. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: guidelines on the management of critically ill adults with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:854-887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1239] [Cited by in RCA: 1360] [Article Influence: 272.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, Liu L, Shan H, Lei CL, Hui DSC, Du B, Li LJ, Zeng G, Yuen KY, Chen RC, Tang CL, Wang T, Chen PY, Xiang J, Li SY, Wang JL, Liang ZJ, Peng YX, Wei L, Liu Y, Hu YH, Peng P, Wang JM, Liu JY, Chen Z, Li G, Zheng ZJ, Qiu SQ, Luo J, Ye CJ, Zhu SY, Zhong NS; China Medical Treatment Expert Group for Covid-19. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708-1720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19202] [Cited by in RCA: 18878] [Article Influence: 3775.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 13. | Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, Cheng Z, Yu T, Xia J, Wei Y, Wu W, Xie X, Yin W, Li H, Liu M, Xiao Y, Gao H, Guo L, Xie J, Wang G, Jiang R, Gao Z, Jin Q, Wang J, Cao B. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35178] [Cited by in RCA: 30123] [Article Influence: 6024.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 14. | Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and Important Lessons From the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak in China: Summary of a Report of 72 314 Cases From the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323:1239-1242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11409] [Cited by in RCA: 11507] [Article Influence: 2301.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Elmokadem AH, Batouty NM, Bayoumi D, Gadelhak BN, Abdel-Wahab RM, Zaky M, Abo-Hedibah SA, Ehab A, El-Morsy A. Mimickers of novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on chest CT: spectrum of CT and clinical features. Insights Imaging. 2021;12:12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Elmokadem AH, Bayoumi D, Abo-Hedibah SA, El-Morsy A. Diagnostic performance of chest CT in differentiating COVID-19 from other causes of ground-glass opacities. EJRN. 2021;52:1-10. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Penn R, David-Sanchez RY, Long J, Barclay W. Aberrant RNA replication products of highly pathogenic avian influenza viruses and its impact in the mammalian associated cytokine storm. Access Microbiol. 2019;1. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Spencer JV, Religa P, Lehmann MH. Editorial: Cytokine-Mediated Organ Dysfunction and Tissue Damage Induced by Viruses. Front Immunol. 2020;11:2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Boomer JS, To K, Chang KC, Takasu O, Osborne DF, Walton AH, Bricker TL, Jarman SD 2nd, Kreisel D, Krupnick AS, Srivastava A, Swanson PE, Green JM, Hotchkiss RS. Immunosuppression in patients who die of sepsis and multiple organ failure. JAMA. 2011;306:2594-2605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1072] [Cited by in RCA: 1272] [Article Influence: 90.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, Fan G, Liu Y, Liu Z, Xiang J, Wang Y, Song B, Gu X, Guan L, Wei Y, Li H, Wu X, Xu J, Tu S, Zhang Y, Chen H, Cao B. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054-1062. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17476] [Cited by in RCA: 18201] [Article Influence: 3640.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Abo-Hedibah SA, Tharwat N, Elmokadem AH. Is chest X-ray severity scoring for COVID-19 pneumonia reliable? Pol J Radiol. 2021;86:e432-e439. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Brealey D, Brand M, Hargreaves I, Heales S, Land J, Smolenski R, Davies NA, Cooper CE, Singer M. Association between mitochondrial dysfunction and severity and outcome of septic shock. Lancet. 2002;360:219-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1030] [Cited by in RCA: 1051] [Article Influence: 45.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Singer M. The role of mitochondrial dysfunction in sepsis-induced multi-organ failure. Virulence. 2014;5:66-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 319] [Cited by in RCA: 410] [Article Influence: 34.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Shenoy S. Coronavirus (Covid-19) sepsis: revisiting mitochondrial dysfunction in pathogenesis, aging, inflammation, and mortality. Inflamm Res. 2020;69:1077-1085. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 24.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Mattone E, Sofia M, Schembari E, Palumbo V, Bonaccorso R, Randazzo V, La Greca G, Iacobello C, Russello D, Latteri S. Acute acalculous cholecystitis on a COVID-19 patient: a case report. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2020;58:73-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ying M, Lu B, Pan J, Lu G, Zhou S, Wang D, Li L, Shen J, Shu J; From the COVID-19 Investigating and Research Team. COVID-19 with acute cholecystitis: a case report. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20:437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Wahid N, Bhardwaj T, Borinsky C, Tavakkoli M, Wan D, Wong T. Acute Acalculous Cholecystitis During Severe COVID-19 Hospitalizations. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115:S794. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 28. | Alhassan SM, Iqbal P, Fikrey L, Mohamed Ibrahim MI, Qamar MS, Chaponda M, Munir W. Post COVID 19 acute acalculous cholecystitis raising the possibility of underlying dysregulated immune response, a case report. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2020;60:434-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Bruni A, Garofalo E, Zuccalà V, Currò G, Torti C, Navarra G, De Sarro G, Navalesi P, Longhini F, Ammendola M. Histopathological findings in a COVID-19 patient affected by ischemic gangrenous cholecystitis. World J Emerg Surg. 2020;15:43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Balaphas A, Gkoufa K, Meyer J, Peloso A, Bornand A, McKee TA, Toso C, Popeskou SG. COVID-19 can mimic acute cholecystitis and is associated with the presence of viral RNA in the gallbladder wall. J Hepatol. 2020;73:1566-1568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Campanile FC, Podda M, Arezzo A, Botteri E, Sartori A, Guerrieri M, Cassinotti E, Muttillo I, Pisano M, Brachet Contul R, D'Ambrosio G, Cuccurullo D, Bergamini C, Allaix ME, Caracino V, Petz WL, Milone M, Silecchia G, Anania G, Agrusa A, Di Saverio S, Casarano S, Cicala C, Narilli P, Federici S, Carlini M, Paganini A, Bianchi PP, Salaj A, Mazzari A, Meniconi RL, Puzziello A, Terrosu G, De Simone B, Coccolini F, Catena F, Agresta F. Acute cholecystitis during COVID-19 pandemic: a multisocietary position statement. World J Emerg Surg. 2020;15:38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Popowicz A, Lundell L, Gerber P, Gustafsson U, Pieniowski E, Sinabulya H, Sjödahl K, Tsekrekos A, Sandblom G. Cholecystostomy as Bridge to Surgery and as Definitive Treatment or Acute Cholecystectomy in Patients with Acute Cholecystitis. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2016;2016:3672416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Wang F, Wang H, Fan J, Zhang Y, Zhao Q. Pancreatic Injury Patterns in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 19 Pneumonia. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:367-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 276] [Cited by in RCA: 325] [Article Influence: 65.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Pandanaboyana S, Moir J, Leeds JS, Oppong K, Kanwar A, Marzouk A, Belgaumkar A, Gupta A, Siriwardena AK, Haque AR, Awan A, Balakrishnan A, Rawashdeh A, Ivanov B, Parmar C, M Halloran C, Caruana C, Borg CM, Gomez D, Damaskos D, Karavias D, Finch G, Ebied H, K Pine J, R A Skipworth J, Milburn J, Latif J, Ratnam Apollos J, El Kafsi J, Windsor JA, Roberts K, Wang K, Ravi K, V Coats M, Hollyman M, Phillips M, Okocha M, Sj Wilson M, A Ameer N, Kumar N, Shah N, Lapolla P, Magee C, Al-Sarireh B, Lunevicius R, Benhmida R, Singhal R, Balachandra S, Demirli Atıcı S, Jaunoo S, Dwerryhouse S, Boyce T, Charalampakis V, Kanakala V, Abbas Z, Nayar M; COVID PAN collaborative group. SARS-CoV-2 infection in acute pancreatitis increases disease severity and 30-day mortality: COVID PAN collaborative study. Gut. 2021;70:1061-1069. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Abate SM, Mantefardo B, Basu B. Postoperative mortality among surgical patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Patient Saf Surg. 2020;14:37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | García Virosta M, Ortega I, Ferrero E, Picardo AL. Diagnostic Delay During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Liver Abscess Secondary to Acute Lithiasic Cholecystitis. Cir Esp (Engl Ed). 2020;98:409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Elliott R, Ohene Baah N, Grossman VA, Sharma AK. COVID-19 Related Mortality During Management of a Hepatic Abscess. J Radiol Nurs. 2020;39:271-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Nahas SC, Meira-JÚnior JD, Sobrado LF, Sorbello M, Segatelli V, Abdala E, Ribeiro-JÚnior U, Cecconello I. Intestinal perforation caused by COVID-19. Arq Bras Cir Dig. 2020;33:e1515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | De Nardi P, Parolini DC, Ripa M, Racca S, Rosati R. Bowel perforation in a Covid-19 patient: case report. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2020;35:1797-1800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | van 't Hof LJ, Pellikaan L, Soonawala D, Roshani H. An Unusual Presentation of Pyelonephritis: Is It COVID-19 Related? SN Compr Clin Med. 2021;1-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Revzin MV, Raza S, Srivastava NC, Warshawsky R, D'Agostino C, Malhotra A, Bader AS, Patel RD, Chen K, Kyriakakos C, Pellerito JS. Multisystem Imaging Manifestations of COVID-19, Part 2: From Cardiac Complications to Pediatric Manifestations. Radiographics. 2020;40:1866-1892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Cheng Y, Luo R, Wang K, Zhang M, Wang Z, Dong L, Li J, Yao Y, Ge S, Xu G. Kidney disease is associated with in-hospital death of patients with COVID-19. Kidney Int. 2020;97:829-838. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1757] [Cited by in RCA: 1815] [Article Influence: 363.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Lee KS, Talenfeld AD, Browne WF, Holzwanger DJ, Harnain C, Kesselman A, Pua BB. Role of interventional radiology in the treatment of COVID-19 patients: Early experience from an epicenter. Clin Imaging. 2021;71:143-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |