Published online Jun 26, 2025. doi: 10.4330/wjc.v17.i6.106445

Revised: April 24, 2025

Accepted: May 24, 2025

Published online: June 26, 2025

Processing time: 114 Days and 4.4 Hours

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is rare among patients aged ≤ 40 years but imposes significant morbidity, psychological distress, and economic burden. App

To describe the characteristics of AMI in young patients, including presentation, risk factors, coronary angiography (CAG) findings, and management strategies.

This retrospective cross-sectional study analyzed 91 patients aged 20–40 years diagnosed with AMI at Mouwasat Hospital Dammam, from June 2020 to May 2023. Data on clinical presentation, cardiovascular risk factors, CAG findings, and treatments were collected from medical records. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize findings.

Of 91 patients (96.7% male, mean age 35.9 years ± 3.4 years), 43.9% were obese (body mass index > 30 kg/m²). Hyperlipidemia was the most prevalent risk factor (69.2%), followed by smoking (49.5%), diabetes mellitus (33.0%), and hypertension (26.4%). ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) was the most common presentation (57.1%). The left anterior descending artery was frequently affected (78.0%), with single-vessel disease predominant (72.5%). Most patients underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) (74.7%), while 8.8% required surgery.

Young AMI patients are predominantly obese males with hyperlipidemia and smoking as key risk factors, pre

Core Tip: This retrospective single-center study aimed to describe characteristics of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in young patients, including presentation, risk factors, coronary angiography findings, and management strategies for AMI in a young population aged less than 40 years. The most common presenting diagnosis was ST-elevation myocardial infarction, with the left anterior descending artery being the most frequently affected artery. Most patients required percutaneous coronary intervention with single stent placement. Obesity and hyperlipidemia were identified as major risk factors for developing AMI in young individuals. Early screening for traditional risk factors and appropriate treatment in the young population is crucial for the primary prevention of AMI.

- Citation: Hegazi Abdelsamie A, Abdelhadi HO, Abdelwahed AT. Acute myocardial infarction in the young: A 3-year retrospective study. World J Cardiol 2025; 17(6): 106445

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1949-8462/full/v17/i6/106445.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v17.i6.106445

Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) is rare among patients aged ≤ 40 years but imposes significant morbidity, psychological distress, and economic burden[1]. Approximately 10% of AMI hospitalizations involve patients under 45 years, underscoring the need to study this group[2]. Compared to older patients, young AMI patients exhibit fewer traditional risk factors (e.g., hypertension, diabetes) but higher rates of smoking, obesity, and non-atherosclerotic causes like spon

Global trends show rising obesity and dyslipidemia in young populations, with smoking contributing to 62%–90% of AMI cases in this age group[5-7]. Family history of coronary artery disease (CAD) also elevates risk, particularly in acute coronary syndrome[2]. Studies like Bhardwaj et al[1] report that young AMI patients are predominantly male with single-vessel disease, unlike the multi-vessel disease typical in older cohorts. This study characterizes AMI in young adults (≤ 40 years) at a single center, focusing on presentation, risk factors, angiographic findings, and management to guide preventive strategies.

This retrospective cross-sectional study analyzed data from the cardiovascular department archive at Mouwasat Hospital Dammam, Saudi Arabia. We included patients aged 20–40 years diagnosed with AMI from June 2020 to May 2023 who underwent coronary angiography (CAG). AMI was defined per the Fourth Universal Definition, requiring clinical evidence of acute myocardial ischemia and a rise and/or fall in cardiac troponin (cTn) above the 99th percentile, with or without ST-segment elevation[8]. Patients aged < 20 years or > 40 years or with undetectable cTn were excluded. Data on clinical presentation, cardiovascular risk factors (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, smoking, obesity), CAG findings, and treatments were extracted from medical records. Obesity was defined as body mass index (BMI) > 30 kg/m². The age cutoff of 40 years aligned with prior studies defining “young” AMI patients, ensuring clinical relevance and adequate sample size[1,4]. The lower limit of 20 years excluded rare pediatric cases. Consecutive sampling included all eligible patients, yielding 91 cases over 3 years, consistent with an estimated 30–35 annual AMI cases in this age group at our center, which performs approximately 1200 percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) annually. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics (means ± SD for continuous variables, frequencies/percentages for categorical variables) in Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 26. No inferential tests were conducted due to the study’s descriptive design. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (No. 2023-D-002), with informed consent obtained from all participants.

From June 2020 to May 2023, 91 patients with AMI (mean age 35.9 years ± 3.4 years, 96.7% male) were studied (Table 1). Most were obese (43.9%, BMI > 30 kg/m²) or overweight (35.2%). Hyperlipidemia was the most common risk factor (69.2%), followed by smoking (49.5%), diabetes mellitus (DM) (33.0%), hypertension (26.4%), and family history of CAD (20.9%) (Table 1).

| Parameter | Value |

| Age (mean ± SD) (years) | 35.9 ± 3.38 |

| Sex | |

| Male | 88 (96.7) |

| Female | 3 (3.3) |

Most patients had a high BMI (30.7 kg/m2 ± 5.8 kg/m2). Of these, 40 (43.9%) patients were obese (BMI more than 30 kg/m2). A total of 32 (35.16%) patients were overweight (BMI ranging between 25- 29.9 kg/m2) (Table 2).

| Category (kg/m2) | |

| Underweight (< 18.5) | 0 |

| Healthy (18.5-24.9) | 19 (20.87) |

| Overweight (25-29.9) | 32 (35.16) |

| Obese (> 30) | 40 (43.9) |

| Body mass index (mean ± SD) | 30.7 ± 5.8 |

Traditional risk factors for ischemic heart disease were nearly similar to those in older patients. A total of 24 (26.37%) patients were hypertensive. DM was present in 30 (33.0%) patients, including 2 (2.2%) patients with type 1 DM, 28 (30.8%) patients with type 2 DM, and 8 (8.8%) patients newly diagnosed during admission. A total of 63 (69.2%) patients had hyperlipidemia, of whom 28 (36.7%) patients were newly diagnosed during admission. Total 49.45% of patients were smokers. Lastly, 20.88% of patients had a positive family history of ischemic heart disease in their first-degree relatives (Table 3).

| Risk factor | Measure | |

| Hypertension | Yes | 24 (26.37) |

| No | 67 (73.63) | |

| DM | Yes | 30 (32.97) |

| No | 61 (67.03) | |

| Type 1 DM | 2 (2.2) | |

| Type 2 DM | 28 (30.76) | |

| Newly diagnosed DM | 8 (8.79) | |

| Dyslipidemia | Yes | 63 (69.23) |

| No | 28 (30.76) | |

| Newly diagnosed dyslipidemia | 25 (39.68) | |

| Smoking status | Yes | 45 (49.45) |

| No | 46 (50.54) | |

| Family history of ischemic heart disease | Yes | 19 (20.88) |

| No | 72 (79.12) |

ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) predominated (57.1%), with anterior STEMI most frequent (38.5%), fo

| Cause of admission | Measure | |

| STEMI | Yes | 52 (57.1) |

| No | 39 (42.86) | |

| Anterior STEMI | 35 (38.46) | |

| Inferior STEMI | 16 (17.58) | |

| Lateral STEMI | 1 (1.1) | |

| Non-STEMI | Yes | 39 (42.86) |

| No | 52 (57.1) |

Regarding the Echocardiographic assessment, mean ejection fraction was 47.8% ± 12.9%. Regarding segmental wall motion abnormality (SWMA), we found anterior and apical hypokinesia (21.98%), inferior/posterior hypokinesia (21.98%), anterior-septal hypokinesia (10.99%), apical akinesia (6.59%), global hypokinesia (13.19%) and lateral hypo

| Parameter | |

| Segmental wall motion | |

| Normal | 17 (18.68) |

| Inferior/posterior hypokinesia | 20 (21.98) |

| Anterior-septal hypokinesia | 9 (10.99) |

| Apical akinesia | 6 (6.59) |

| Anterior and apical hypokinesia | 20 (21.98) |

| Global hypokinesia | 12 (13.19) |

| Lateral hypokinesia | 6 (6.59) |

| Ejection fraction range (mean ± SD) | 47.8% ± 12.92% |

CAG showed the left anterior descending artery (LAD) as the most affected (78.0%), followed by the right coronary artery (RCA) (54.9%), left circumflex artery (LCX) (44.0%), left main (LM) (5.5%) and ramus artery (5.5%) (Table 6).

| Parameter | n = 91 | |

| LM | Normal | 86 (94.51) |

| Significant lesion | 4 (4.4) | |

| Total occlusion (dissection) | 1 (1.1) | |

| LAD | Normal | 20 (21.98) |

| Significant lesion | 23 (25.28) | |

| Non-significant lesion | 12 (13.19) | |

| Total occlusion | 18 (19.78) | |

| Subtotal occlusion | 9 (9.89) | |

| Thrombus | 4 (4.39) | |

| Bridge | 3 (3.3) | |

| Total D1 | 2 (2.2) | |

| LCX | Normal | 51 (56.04) |

| Significant lesion | 16 (17.58) | |

| Non-significant lesion | 18 (19.78) | |

| Total occlusion | 3 (3.3) | |

| Subtotal occlusion | 2 (2.2) | |

| Dissection | 1 (1.1) | |

| RCA | Normal | 41 (45.05) |

| Significant lesion | 11 (12.09) | |

| Non-significant lesion | 20 (21.98) | |

| Total occlusion | 9 (9.89) | |

| Subtotal occlusion | 8 (8.79) | |

| Thrombus | 2 (2.2) | |

| Ramus | Normal | 86 (94.51) |

| Significant lesion | 1 (1.1) | |

| Non-significant lesion | 4 (4.4) | |

| n = 79 | ||

| Culprit artery | LAD | 51 (56.04) |

| RCA | 17 (18.68) | |

| LCX | 11 (12.09) | |

| n = 84 | ||

| Frequency of affected vessels | Single vessel disease | 66 (72.53) |

| Two vessel disease | 8 (8.79) | |

| Three vessel disease | 5 (5.49) | |

| LM + three vessel disease | 4 (4.4) | |

| LM + two vessel disease | 1(1.1) | |

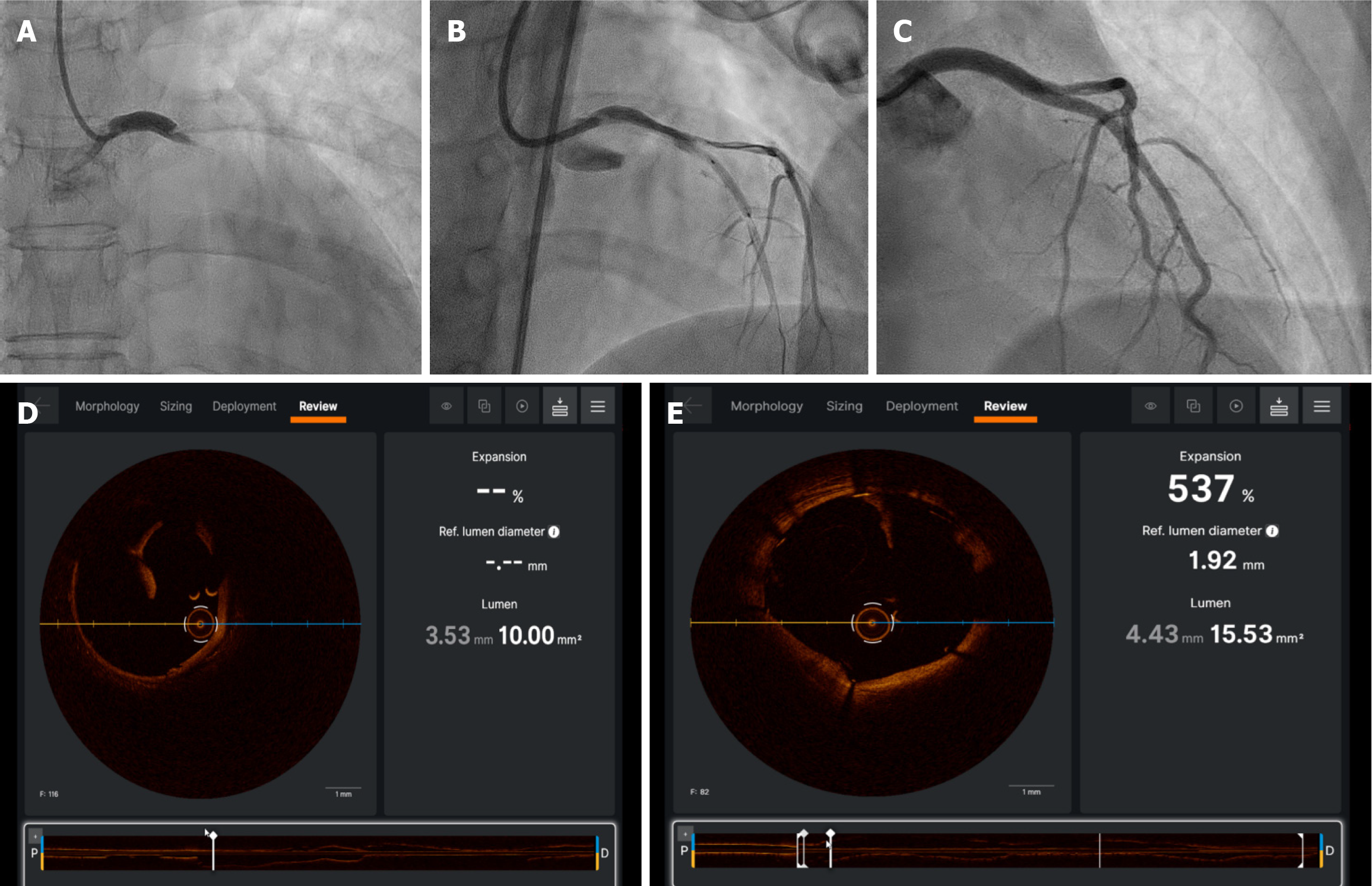

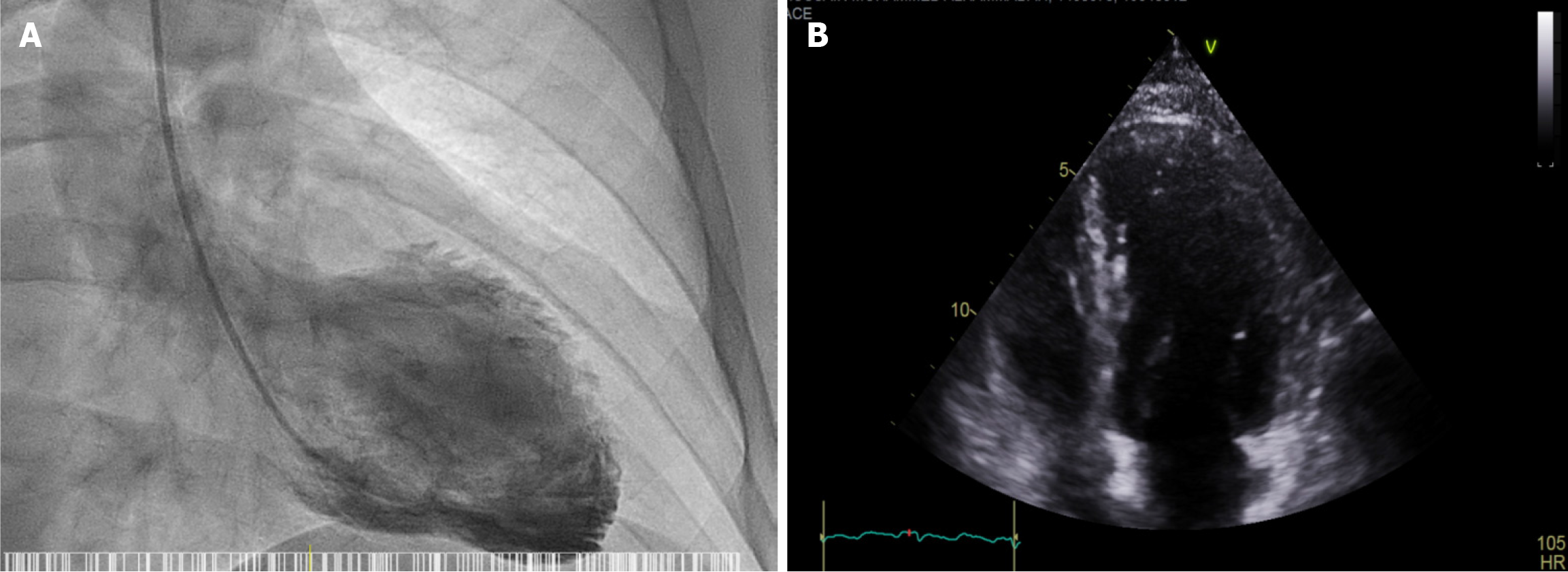

Single-vessel disease was common (72.5%), followed by double-vessel (8.8%) and three-vessel disease (5.5%), LM and three vessel disease (4.4%), and the least common was LM and two vessel disease (1.1%). It is worth mentioning that this particular patient was a 25-year-old postpartum female who presented with extensive anterior STEMI and was found to have SCAD involving LM, LAD and LCX arteries (Table 6 and Figure 1).

Furthermore, we found that LAD was the most commonly affected culprit artery (56.04%), followed by RCA (18.68%), and lastly LCX (12.09%) (Table 6).

Obstructive CAD was observed in 83.5% of patients, while myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arte

| Final diagnosis | n = 91 |

| Obstructive CAD | 76 (83.51) |

| Myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries | 13 (14.28) |

| Non-obstructive CAD | 5 (5.5) |

| Normal coronary | 6 (6.59) |

| Takotsubo cardiomyopathy | 1 (1.1) |

| Aortic valve insufficiency induced cardiomyopathy | 1 (1.1) |

| Coronary artery dissection | 2 (2.2) |

| With no obstructive lesion | 1 (1.1) |

| With obstructive lesion | 1 (1.1) |

Management was classified into PCI with balloon dilatation and stenting (74.7%). Thrombus aspiration without sten

| Conclusion | n = 91 | |

| Intervention | 78 (85.71) | |

| PCI | Total number | 68 (74.72) |

| PCI with 1 DES | 57 (62.64) | |

| PCI with 2 DES | 6 (6.59) | |

| PCI with 3 DES | 1 (1.1) | |

| PCI with 5 DES | 1 (1.1) | |

| PCI with 1 DES and 1 DEB | 1 (1.1) | |

| PCI with 2 DES and 1 DEB | 1 (1.1) | |

| PCI with 1 DES and 3 DEB | 1 (1.1) | |

| Thrombus aspiration | 2 (2.2) | |

| Open heart surgery | Total number | 8 (8.79) |

| MVD for CABG | 6 (6.59) | |

| MVD for CABG + AVR | 1 (1.1) | |

| AVR and Bentall procedure | 1 (1.1) | |

| Medical treatment | 6 (6.6) | |

| Normal coronaries | 7 (7.7) | |

| Parameter | Value (n = 91) |

| Age (years, mean ± SD) | 35.9 ± 3.4 |

| Male | 88 (96.7) |

| Body mass index (kg/m²) (mean ± SD) | 30.7 ± 5.8 |

| Obese (> 30) | 40 (43.9) |

| Overweight (25–29.9) | 32 (35.2) |

| Risk factors | |

| Hyperlipidemia | 63 (69.2) |

| Smoking | 45 (49.5) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 30 (33.0) |

| Hypertension | 24 (26.4) |

| Family history of CAD | 18 (20.9) |

| Presentation | |

| STEMI | 52 (57.1) |

| Non-STEMI | 39 (42.9) |

| Coronary angiography findings | |

| Obstructive CAD | 76 (83.51) |

| Myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries | 13 (14.28) |

| Coronary artery dissection | 2 (2.2) |

| Management | |

| Percutaneous intervention | 70 (76.92) |

| Surgery | 8 (8.79) |

| Medical treatment | 6 (6.6) |

| Normal coronaries | 7 (7.7) |

This study characterizes AMI in young adults (≤ 40 years), revealing a predominance of male patients (96.7%) with obesity (43.9%) and traditional risk factors like hyperlipidemia (69.2%) and smoking (49.5%). These align with Bhardwaj et al[1], who noted AMI in young patients as primarily male with similar risk profiles. Regarding obesity, the guidelines recommend an ideal BMI of 25 kg/m2 and suggest a reduction in body weight if BMI > 30 kg/m2 or when waist circumference is > 102 cm for men and > 88 cm for women[5]. In the current study, we noticed that the mean BMI of the patients is high (30.7 kg/m2 ± 5.8 kg/m2). Most of our patients (79.12%) were overweight or obese. Previous Literature found that obesity is the most prevalent risk factor in young adults[4]. Obese individuals have a higher incidence of cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension, DM and dyslipidemia. Therefore, this group of patients has higher morbidity and mortality associated with cardiovascular disorders[5]. Moreover, cigarette smoking is the most important and consistent risk factor for CAD, with contribution ranging from 62% to 90% in various literature[6,7]. In previous studies, smokers comprised 78.5% of the population[9]. Our study detected that 49.45% of patients were active smokers. Typically, a young AMI patient is an overweight or obese, hyperlipidemic and a smoker. Therefore, implementing targeted screening programs for young adults with obesity or family history of CAD, and promoting smoking cessation campaigns is crucial.

Unlike older AMI patients, where multi-vessel disease and hypertension are prevalent, our cohort showed single-vessel disease (72.5%) and lower hypertension rates (26.4%)[10]. This suggests a distinct pathophysiology driven by modifiable factors like smoking and obesity rather than chronic vascular changes.

The clinical significance lies in preventive opportunities. High rates of undiagnosed hyperlipidemia (39.7%) and diabetes (8.8%) highlight the need for routine screening in young adults, especially those with a family history of CAD (20.9%). Smoking, present in nearly half of cases, is a key target for public health interventions, as cessation could reduce AMI incidence significantly[6]. Our MINOCA rate (14.3%) matches prior studies (Al-Ali et al[11], 15.6%; von Korn et al[12], 8.8%), emphasizing the role of advanced diagnostics [e.g., intravascular ultrasound (IVUS), optical coherence tomo

Angiographically, in young patients with AMI, STEMI was more prevalent than non-STEMI. CAD was more fre

Compared to classic AMI populations, young patients required simpler interventions (62.6% needed one stent), reflecting less extensive CAD. The same finding was described in Andreenko et al[15] study. However, SCAD (2.2%) is an infrequent finding in young AMI patients in our study, notably in a postpartum female, underscores the need to consider non-traditional etiologies in young women, as reported by Tweet et al[16]. These differences advocate for tailored diagnostic and management approaches to optimize outcomes in young AMI patients.

In order to properly evaluate and treat non-obstructive CAD, European guidelines put a clear definition for MINOCA. The diagnosis of MINOCA must meet 3 criteria. First, a definitive diagnosis of AMI must be made (the same as that of AMI caused by obstructive CAD). Second, CAG must show non-obstructive coronary disease, i.e., no obstructive coronary disease (i.e., no coronary stenosis ≥ 50%) is found in any possible infarction-related Angiography, including normal coronary arteries (no stenosis < 30%) and mild coronary atherosclerosis (stenosis > 30 and < 50%). Third, there is no clinical finding of other specific diseases that cause AMI, e.g., myocarditis and pulmonary embolism[8]. Additional diagnostics, such as IVUS, OCT, and cardiovascular magnetic resonance, for accurate diagnosis.

Previous studies faced similar difficulties in building up the provisional diagnosis of this particular type of patients[17]. The current study revealed that 14.29% of the patients with AMI lacked significant coronary stenosis according to the CAG procedure performed during the hospital admission; which was consistent with the results of Al-Ali et al[11] study (15.6%) and von Korn et al[12] study (8.8%).

Angina or ischemia with no obstructive CAD (ANOCA/INOCA) is another entity of non-obstructive CAD. It is frequently underdiagnosed and undertreated condition, primarily due to the limitations of current diagnostic tools. The condition is proposed to arise from two mechanisms: (1) Coronary microvascular dysfunction, leading to myocardial sub perfusion during stress; and (2) Microvascular spasm at rest. The definitive diagnostic approach involves invasive CAG with assessments of endothelial-independent microvascular dysfunction in response to adenosine, and endothelial-dependent microvascular dysfunction in response to acetylcholine, as well as evaluations for epicardial and microva

Young AMI patients are predominantly obese males with hyperlipidemia and smoking as key risk factors, presenting with STEMI and single-vessel disease amenable to PCI. Traditional risk factors, such as hypertension, DM, and hyperlipidemia, are increasing in the young population, who are often not aware of their condition and its potential complications. Early detection through screening programs and proper treatment would significantly impact primary prevention of AMI in young adults. Smoking prevention and cessation remain crucial targets to reduce the incidence of AMI in this group.

We extend our sincere gratitude to Dr. Ahmed Atef Elbekiey, Dr. Ahmed Mostafa, and Mr. Eyad Abu Saad, Cath lab Technician, for their invaluable guidance, insightful discussions, and unwavering support throughout this research endeavor. Their expertise and encouragement have significantly enriched our work.

| 1. | Bhardwaj R, Kandoria A, Sharma R. Myocardial infarction in young adults-risk factors and pattern of coronary artery involvement. Niger Med J. 2014;55:44-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Rubin JB, Borden WB. Coronary heart disease in young adults. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2012;14:140-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wahrenberg A, Magnusson PK, Discacciati A, Ljung L, Jernberg T, Frick M, Linder R, Svensson P. Family history of coronary artery disease is associated with acute coronary syndrome in 28,188 chest pain patients. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2020;9:741-747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mirza AJ, Taha AY, Khdhir BR. Risk factors for acute coronary syndrome in patients below the age of 40 years. Egypt Heart J. 2018;70:233-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Foussas S. Obesity and Acute Coronary Syndromes. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2016;57:63-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wolfe MW, Vacek JL. Myocardial infarction in the young. Angiographic features and risk factor analysis of patients with myocardial infarction at or before the age of 35 years. Chest. 1988;94:926-930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Weinberger I, Rotenberg Z, Fuchs J, Sagy A, Friedmann J, Agmon J. Myocardial infarction in young adults under 30 years: risk factors and clinical course. Clin Cardiol. 1987;10:9-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Thygesen K. 'Ten Commandments' for the Fourth Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction 2018. Eur Heart J. 2019;40:226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lakka HM, Lakka TA, Tuomilehto J, Salonen JT. Abdominal obesity is associated with increased risk of acute coronary events in men. Eur Heart J. 2002;23:706-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 246] [Cited by in RCA: 243] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sinha SK, Krishna V, Thakur R, Kumar A, Mishra V, Jha MJ, Singh K, Sachan M, Sinha R, Asif M, Afdaali N, Mohan Varma C. Acute myocardial infarction in very young adults: A clinical presentation, risk factors, hospital outcome index, and their angiographic characteristics in North India-AMIYA Study. ARYA Atheroscler. 2017;13:79-87. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Al-Ali MH, Farhan HA. Troponin positive acute coronary syndrome with and. |

| 12. | von Korn H, Graefe V, Ohlow MA, Yu J, Huegl B, Wagner A, Gruene S, Lauer B. Acute coronary syndrome without significant stenosis on angiography: characteristics and prognosis. Tex Heart Inst J. 2008;35:406-412. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Anjum M, Zaman M, Ullah F. Are Their Young Coronaries Old Enough? Angiographic Findings In Young Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2019;31:151-155. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Fournier JA, Sánchez A, Quero J, Fernández-Cortacero JA, González-Barrero A. Myocardial infarction in men aged 40 years or less: a prospective clinical-angiographic study. Clin Cardiol. 1996;19:631-636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Andreenko EY, Yavelov IS, Loukianov ММ, Vernohaeva AN, Drapkina OM, Boytsov SA. Ischemic Heart Disease in Subjects of Young Age: Current State of the Problem. Features of Etiology, Clinical Manifestation and Prognosis. Kardiologiia. 2018;58:24-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tweet MS, Hayes SN, Pitta SR, Simari RD, Lerman A, Lennon RJ, Gersh BJ, Khambatta S, Best PJ, Rihal CS, Gulati R. Clinical features, management, and prognosis of spontaneous coronary artery dissection. Circulation. 2012;126:579-588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 539] [Cited by in RCA: 642] [Article Influence: 49.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zasada W, Bobrowska B, Plens K, Dziewierz A, Siudak Z, Surdacki A, Dudek D, Bartuś S. Acute myocardial infarction in young patients. Kardiol Pol. 2021;79:1093-1098. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ashokprabhu ND, Quesada O, Alvarez YR, Henry TD. INOCA/ANOCA: Mechanisms and novel treatments. Am Heart J Plus. 2023;30:100302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ford TJ, Stanley B, Sidik N, Good R, Rocchiccioli P, McEntegart M, Watkins S, Eteiba H, Shaukat A, Lindsay M, Robertson K, Hood S, McGeoch R, McDade R, Yii E, McCartney P, Corcoran D, Collison D, Rush C, Sattar N, McConnachie A, Touyz RM, Oldroyd KG, Berry C. 1-Year Outcomes of Angina Management Guided by Invasive Coronary Function Testing (CorMicA). JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13:33-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 29.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |