Published online Mar 27, 2016. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v8.i3.266

Peer-review started: September 1, 2015

First decision: September 29, 2015

Revised: December 12, 2015

Accepted: January 5, 2016

Article in press: January 7, 2016

Published online: March 27, 2016

Processing time: 202 Days and 20.3 Hours

AIM: To review the current data about the success rates of fibrin sealant use in pilonidal disease.

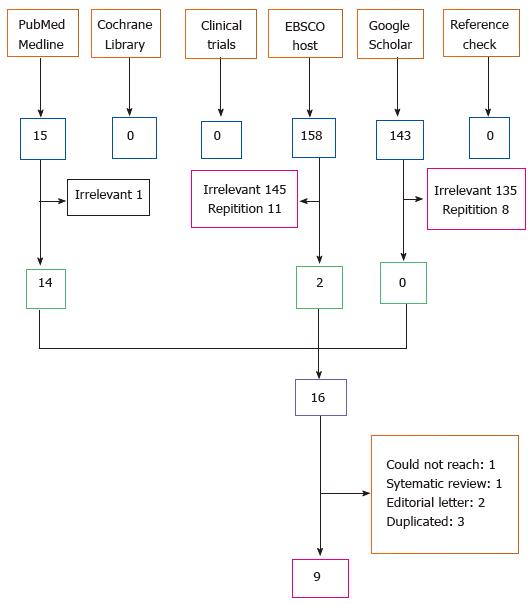

METHODS: Fibrin sealant can be used for different purposes in pilonidal sinus treatment, such as filling in the sinus tracts, covering the open wound after excision and lay-open treatment, or obliterating the subcutaneous dead space before skin closure. We searched Pubmed, Google-Scholar, Ebsco-Host, clinicaltrials, and Cochrane databases and found nine studies eligible for analysis; these studies included a total of 217 patients (84% male, mean age 24.2 ± 7.8).

RESULTS: In cases where fibrin sealant was used to obliterate the subcutaneous dead space, there was no reduction in wound complication rates (9.8% vs 14.6%, P = 0.48). In cases where sealant was used to cover the laid-open area, the wound healing time and patient comfort were reported better than in previous studies (mean 17 d, 88% satisfaction). When fibrin sealant was used to fill the sinus tracts, the recurrence rate was around 20%, despite the highly selected grouping of patients.

CONCLUSION: Consequently, using fibrin sealant to decrease the risk of seroma formation was determined to be an ineffective course of action. It was not advisable to fill the sinus tracts with fibrin sealant because it was not superior to other cost-effective and minimally invasive treatments. New comparative studies can be conducted to confirm the results of sealant use in covering the laid-open area.

Core tip: Fibrin sealant use in pilonidal disease treatment may involve filling in the sinus tracts, covering the laid-open area after excision, or obliterating the subcutaneous dead space before skin closure. This systematic review demonstrates that when the fibrin sealant was used to obliterate the subcutaneous dead space, there was no reduction in wound complications. It was unadvisable to fill the sinus tracts because it was not superior to the other more cost-effective treatments with a 20% recurrence rate. More studies are necessary for sealant use in covering the laid-open area, which has promising results, predicting shorter wound healing time and increased patient satisfaction.

- Citation: Kayaalp C, Ertugrul I, Tolan K, Sumer F. Fibrin sealant use in pilonidal sinus: Systematic review. World J Gastrointest Surg 2016; 8(3): 266-273

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v8/i3/266.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v8.i3.266

Pilonidal sinus is a benign disease seen more commonly in young males and negatively alters the quality of life. Its prevalence was reported as 26 cases per 100000 people[1]. The mainstay of pilonidal sinus treatment begins with the surgical excision of the sinus tracts, which is followed by either primary closure after excision or laying open the wound for secondary healing; these are the most commonly preferred surgical methods. However, these traditional techniques prolong the recovery period, cause a delay in returning to daily life, and ultimately interrupt the educational or professional lives of these young and active patients.

Fibrin sealant may be used for different purposes in pilonidal sinus surgery. Filling the sinus tracts with the fibrin sealant instead of surgically removing the sinus tracts has been described in the literature as a minimally invasive technique. Additionally, the open surface of the surgical area may be covered with the fibrin seal in the lay-open technique. A third option requires that the potential dead space that is formed after the total excision and primary closure of the defect may be obliterated by the fibrin sealant. All these methods are used in order to accelerate the recovery period, to decrease morbidity, and to enable a quick return to work. Our aim in this review was to collect all accessible data in the literature on the treatment of pilonidal disease with fibrin sealant and to make a prediction about the promising treatments.

The databanks of http://http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed, http://http://www.cochrane.org, scholar.google.com and web.a.ebscohost.com were last searched on the 3rd of June, 2015, using the key words [(pilonidal*) and (glue* OR sealant*)]. All varieties of researches, including congressional summaries describing the patient data about the treatment, were analyzed. Two reviewers (IE & CK) determined the selection of the searched articles on http://http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed and http://http://www.cochrane.org by the key words in all fields. Some studies were excluded due to the nature of their content (editorial letters, reviews, duplicated studies). Later, a search to scholar.google.com and web.a.ebscohost.com were done by the key words in titles of the studies. Lastly, http://www.clinicaltrials.gov was also searched. We performed an additional reference cross check as well.

As we were scanning the literature for the pilonidal sinus treatment modalities using fibrin glue, publications concerning the use of fibrin glue to fill the tracts without excision, publications concerning covering the defect following surgical excision and publications concerning filling the cavity with fibrin glue before primary closure were all included in this analysis. Treatments of pilonidal sinuses outside of the sacrococcygeal area (interdigital, umbilical, penile, vulvar) were excluded.

We used no limitations to the patient and journal features. All patients were were accepted for analysis if there were enough data. There was no restrain with regard to article language, country, or journal. In cases of disagreement during analysis, a consensus of the two researcher authors was necessary for the acceptance of the studies. Data for affiliation, number of patients, age, gender, history of prior pilonidal surgery, method of application, complications, recurrence, time to heal, length of follow-up period, success, clinical findings, inclusion and exclusion criteria, body mass index, intra-operative and postoperative complications, duration of surgery, postoperative pain, postoperative hospital stay, time off work, and overall satisfaction were analyzed.

Data were organized into tables, and column sums were done including percentages, means ± standard deviations, or the ranges. If the studies reported the median and range, the mean and standard deviation were estimated by Hozo et al[2] method. Percentages were preferred for the dichotomous parameters and means for the continuous parameters[3]. The Chi-square test or the Fisher exact test (if expected values were less than 5) and Student’s t test were used. (SPSS 17.0). P < 0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

A total of nine publications were found that detailed the use of fibrin sealant in pilonidal sinus treatment[4-12] (Figure 1). These publications included 217 patients that were treated between June 2001 and December 2013 (Table 1). Eighty-four percent of the patients were male, and their mean age was 24.2 ± 7.8 (ranged 12-70). One of the studies was conducted within a pediatric age group; the mean age for participants in this study was 14.5 and their mean body weight was 73 kg[12]. The inclusion criteria and the surgical techniques used in these studies constituted sufficient heterogeneity (Tables 2 and 3). The studies were gathered into three subgroups depending on the application technique of the fibrin glue (Table 3). Fibrin sealant was used to obliterate the dead space before wound closure in three studies[4,8,9]. In two other studies, it was used to cover the defect after the excision and lay-open technique[6,7]. In the remaining four studies, the sinus tracts were filled with the fibrin sealant without performing any surgery, which was intended to constitute a definitive treatment[5,10-12]. Thirty-nine percent of all these interventions were performed under local anesthesia. An average of 3.8 mL (ranged 1-6 mL) of fibrin glue was used; drains were used in only 7.3% of these cases (Table 4).

| Ref. | Year | Country | Study period | No. | Male | Age | BMI or weight |

| Greenberg et al[4] | 2004 | Israel | Jun 2001 to Dec 2001 | 30 | 22 | 23.5 ± 2.8 (17-44) | NA |

| Lund et al[5] | 2005 | United Kingdom | NA | 6 | 6 | 28.5 ± 5.5 (22-44) | NA |

| Seleem et al[6] | 2005 | Saudi Arabia | Sep 2001 to Feb 2004 | 25 | 23 | 26.4 ± 8.5 (17-50) | NA |

| Patti et al[7] | 2006 | Italy | NA | 8 | 8 | 21.8 ± 6.5 | NA |

| Altinli et al[8] | 2007 | Turkey | Jan 2003 to Jan 2004 | 16 | 16 | 24.5 ± 6.0 | 25.7 + 4.1 kg/m2 |

| Sözen et al[9] | 2011 | Turkey | Jan 2008 to Mar 2008 | 25 | 25 | 22.5 ± 4.0 (20-36) | 26 kg/m2 |

| Elsey et al[10] | 2013 | United Kingdom | Mar 2007 to Sep 2011 | 57 | 42 | 26.0 ± 13.3 (17–70) | NA |

| Isik et al[11] | 2014 | Turkey | Dec 2007 to Dec 2011 | 40 | 32 | 24.0 ± 8.5 (16-50) | NA |

| Smith et al[12] | 2014 | United Kingdom | Aug 2006 to Dec 2013 | 10 | NA | 14.5 ± 1.0 (12–16) | 73 kg |

| Total | Jun 2001 to Dec 2013 | 217 | 84% | 24.2 ± 7.8 (12-70) |

| Ref. | No. | Inclusion and exclusion criteria | Recurrent |

| Greenberg et al[4] | 30 | No exclusion criteria | 8 |

| Lund et al[5] | 6 | 3-4 openings and no large cavity | 3 |

| Seleem et al[6] | 25 | 1-3 openings, no prior surgery, no infection | 0 |

| Patti et al[7] | 8 | 3 < openings, no prior surgery, no infection, no large cavity or distant orifice | 0 |

| Altinli et al[8] | 16 | No prior surgery | 0 |

| Sözen et al[9] | 25 | No prior surgery, no infection, no lateral extension < 3 cm | 0 |

| Elsey et al[10] | 57 | No infection, no very scarred cases due to repeated episodes or surgeries | 2 |

| Isik et al[11] | 40 | Only 1 opening, no prior surgical or medical treatment, no infection | 0 |

| Smith et al[12] | 10 | No exclusion criteria | 0 |

| Total | 217 | 13 (6%) |

| Ref. | No. | Surgical procedure | Aim of using fibrin sealant |

| Greenberg et al[4] | 30 | Excision and primary closure | Obliterate the dead space under the wound |

| Lund et al[5] | 6 | No sinus excision, only cleaning the tracts | Fill the tracts with sealent |

| Seleem et al[6] | 25 | Excision and lay open | Overlap the open wound with sealent |

| Patti et al[7] | 8 | Excision and lay open | Overlap the open wound with sealent |

| Altinli et al[8] | 16 | Excision and closure with Limberg flap | Obliterate the dead space under the wound |

| Sözen et al[9] | 25 | Excision and closure with Karydakis flap | Obliterate the dead space under the wound |

| Elsey et al[10] | 57 | No sinus excision, only cleaning the tracts | Fill the tracts with sealent |

| Isik et al[11] | 40 | No sinus excision, only cleaning the tracts | Fill the tracts with sealent |

| Smith et al[12] | 10 | No sinus excision, only cleaning the tracts | Fill the tracts with sealent |

| Ref. | No. | Anesthesia | Amount of glue | Drain |

| Greenberg et al[4] | 30 | General or spinal | 2-4 mL | None |

| Lund et al[5] | 6 | General | 1-2 mL | None |

| Seleem et al[6] | 25 | Local (n = 23), general (n = 2) | NA | None |

| Patti et al[7] | 8 | Local | 1.9 ± 0.6 mL | None |

| Altinli et al[8] | 16 | Spinal | 6 mL | Yes |

| Sözen et al[9] | 25 | NA | 6 mL | None |

| Elsey et al[10] | 57 | General | NA | None |

| Isik et al[11] | 40 | Local | 2-4 mL | None |

| Smith et al[12] | 10 | General | NA | None |

| Total | 217 | Local 39% | 3.8 (1-6) | 7.3% |

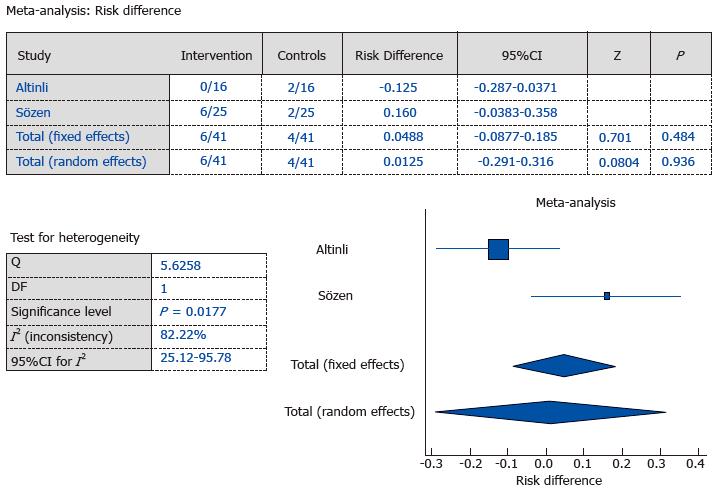

In three studies, fibrin sealant was applied in order to obliterate the subcutaneous dead space[4,8,9]. There were no recurrences in any of these cases after a mean follow-up period of 15.2 mo (Table 5). However, wound-related complications were observed in 16.4% of the patients. In one study, the authors declared that postoperative purulent drainage after fibrin sealant application was more frequent in cases requiring recurrent surgeries[4]. In another study, the amount of drainage decreased within the fibrin sealant group, but instances of wound complications did not decrease significantly[8]. In another study, fibrin sealant was replaced with a subcutaneous drain; there were no wound-related complications within the no-drain fibrin sealant group[9]. In the studies with control groups[8,9], it was observed that use of the fibrin sealant did not decrease wound complication rates (control groups 9.8% vs sealant groups 14.6%; P = 0.48) (Figure 2).

Fibrin sealant was used in two studies in order to shorten the wound’s healing period and to mitigate the negative effects associated with an open wound following surgical excision[6,7] (Table 6). Healing periods for these patients were around 17 d and the morbidity rate was only 6%, which mainly involved early detachment of the fibrin sealant. When the fibrin sealant detached from the wound, either a new sealant was applied to the wound[7], or it was left open for secondary intention[6]. Work-off time of those patients was reported to be lower than expected (5.3 + 2.1 d)[7]. In this group of patients, there were no recurrences reported and the patient satisfaction rate was reported to be 88% (Table 6).

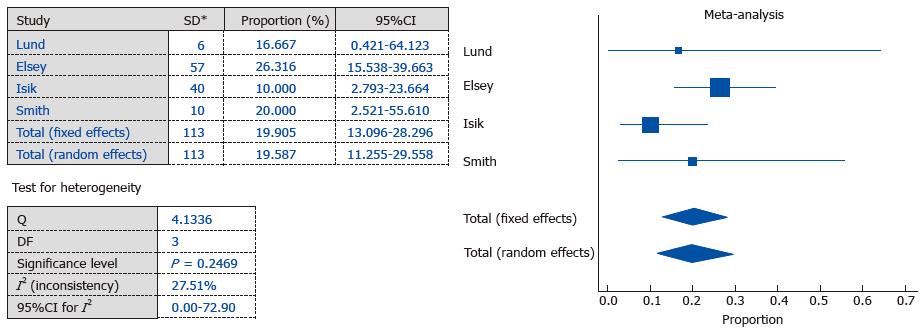

Simply filling the pilonidal sinus tracts with fibrin sealant after curettage was used in four studies conducted with 113 patients as a minimally invasive treatment modality. Work-off time was generally less than 7 d, and the morbidity rates were generally reported to be less than 1% (Table 7). The success rate for this group of patients was about 80%, after a mean follow up of 21.7 mo. In other words, the recurrence rates were around 20% (Figure 3).

The fibrin sealant is composed of two ingredients; human fibrinogen and bovine thrombin. When the two of these are combined, the thrombin converts the fibrinogen into fibrin in less than a minute. This 3 dimensional fibrin plug is used as a haemostatic or a sealing agent. Fibrin was first used as a local haemostatic material in Germany about 100 years ago[13]. In the 1940s, it was used to repair the peripheral nerves[14] and to keep skin grafts in place[15]. Although it has been used commercially in Europe since 1972, it was not approved by the FDA for use in the United States[16] until around 1998. Nowadays, fibrin sealant has been approved by the FDA for the following uses; hemostasis in surgical interventions, sealing of the colon during colostomy closure, and fixation of skin grafts given to burn patients[16,17]. The other uses for fibrin sealants that fall outside of the FDA indications include prevention of seroma formation, fixation of mesh, and fistula tract closure[16].

Recently, there has been a tendency to use minimally invasive surgical techniques in the treatment of pilonidal sinus, as with other surgically-treated diseases[18]. Ideal treatment of pilonidal sinus should be conducted in outpatient settings under local anesthesia, have less postoperative pain, fast recovery, high success rates, and low costs[18]. Fibrin sealant can be used for three purposes; (1) to obliterate the dead space under a closed wound; (2) to cover an open wound; (3) for primary treatment of sinus tracts in which they are filled with the sealant.

Seroma formation is a commonly observed complication following primary closure or flap closure of a wound. The collection of seroma leads to dehiscence of the wound, prolongation of the healing period, necessitates increased wound dressing changes, and causes a decrease in the patient’s overall comfort and satisfaction. Deep sutures or use of drains are the most common techniques for closing the dead space, which prevents seroma formation. However, deep sutures increase pain and invert the natal cleft, which is ought to be flattened. The presence of the drains detracts from patient comfort, increases the workload associated with wound care, and raises the risk of infection. It is suspected that the use of the fibrin sealant may decrease seroma formation and decrease the need for the use of drains. But this analysis did not reveal that the fibrin sealant is effective in decreasing wound complications. Similar seroma problems were reported in mastectomy and axilla dissection cases, and many studies have been conducted with the fibrin sealant as a method of seroma prevention[19]. Studies on fibrin sealant use in breast cancer surgery laid the groundwork for the use of fibrin sealant in treatment of pilonidal sinus patients. But the evidence-based medicine showed that the fibrin sealant did not influence the incidence of seromas, wound infections, overall complications, and the length of hospital stays for patients undergoing breast cancer surgery[19]. The fibrin sealant’s inability to prevent seroma formation can be explained by its tendency to liquefy as it dissolves, and that it causes a tissue reaction[20]. With the help of this analysis and similar studies conducted in mastectomy patients, we can conclude that the use of the fibrin sealant to obliterate the subcutaneous dead space is not very effective in preventing wound complications. Additionally, it has been observed that the use of the fibrin sealant leads to higher rates of subcutaneous fluid accumulation than treatment with drains[9].

To this aim, the fibrin sealant can be used to decrease pain, dressing changes, and healing period. Nevertheless, a control group is needed to confirm that fibrin sealant does indeed achieve these desired ends. The absence of a control group in these studies[6,7] makes it difficult to objectively evaluate the effectiveness of this technique. Without any comparative studies having been conducted, this technique cannot be proposed as an acceptable application.

Fibrin sealant may be used as a sole treatment modality in pilonidal sinus treatment. Filling the sinus tracts with fibrin sealant without any other surgery has the advantages of less pain, shorter recovery period and a rapid return to daily life, and fewer dressing changes. Although it is generally recommended that this procedure be performed under local anesthesia, two thirds of all the reported cases were, surprisingly, performed under general anesthesia (Tables 3 and 4). Since even surgical excisions of the pilonidal sinus and flap procedures are performed under local anesthesia[21], the use of the general anesthesia for a mere tract debridement and fibrin sealant application may be supererogatory. According to us, general or regional anesthesia should be used under special circumstances (pediatric patients, jitters, history of adverse reactions to local anesthesia, etc.). In this meta-analysis, an 80% success rate for filling sinus tracts with fibrin sealant is pleasing. However, this result should be approached with caution. In one study, there was a 39% rate of non-responders[10]. Another study included sinuses only with one orifice and cases without any purulent drainage (may be asymptomatic)[11]. There was no study that was conducted with a sufficient number of symptomatic patients. Additionally, there was no information about the effect of repetitive applications of the sealant on this success rate. The results of single applications were also unknown. Conditions requiring repeated applications were not identified. Similar analyses were performed previously for phenol application in pilonidal disease; a success rate of 70% in single application and a success rate of 86.7% in repetitive applications were reported[22,23]. Even if the 80% success rate is to be accepted as accurate, it nevertheless does not constitute an advantage over phenol application. Furthermore, fibrin sealant is much more expensive than phenol. In cases where repeated sealant applications are necessary, the use of phenol may offer an advantage due to the higher cost of fibrin. We may comfortably claim that the treatment of pilonidal tracts with fibrin sealant is not definitively superior to other minimally invasive methods. Additionally, the higher cost of fibrin sealant does not justify its routine use in filling sinus tracts as a primary treatment modality.

A review was published in 2012 about the fibrin sealant use in pilonidal sinus[24]. In this review, which analyzed only 5 publications with a total number of 85 patients, researchers declared that adjuvant fibrin sealant in the treatment of pilonidal sinus was a promising technique, and they justified more research about it[24]. In the last four years, new studies have been conducted; our systematic review analyzed 9 publications, which included 217 patients altogether. Analyzing more patients than the previously published review provided us to make some specific comments. However, it is obvious that more studies are still necessary for clear comments.

The limitations of our study were (1) a low number of randomized controlled trials; (2) heterogeneity of the studies involved; and (3) a lack of subgroup analysis for special groups (pediatric cases, recurrent cases, etc.). Because of these constraints, we used descriptive statistics in general, and sometimes meta-analysis. Despite these limitations, some results of this analysis are able to justify certain conclusions. In our opinion, the use of fibrin sealant in preventing subcutaneous seroma formation is not advantageous. The use of the fibrin sealant in order to fill the sinus tracts is also not advised, as its success rate was not greater than that of more cost-effective minimally invasive methods. New studies must be conducted regarding fibrin sealant use in covering wounds after excision and lay-open.

Fibrin sealant may be used for different purposes in pilonidal sinus surgery. All the methods are used in order to accelerate the recovery period, to decrease morbidity, and to enable a quick return to work. The aim in this review was to collect all accessible data in the literature on the treatment of pilonidal disease with fibrin sealant and to make a prediction about the promising treatments.

Fibrin was first used as a local haemostatic material in Germany about 100 years ago. In the 1940s, it was used to repair the peripheral nerves and to keep skin grafts in place. Although it has been used commercially in Europe since 1972, it was not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in the United States until around 1998.

Recently, there has been a tendency to use minimally invasive surgical techniques in the treatment of pilonidal sinus, as with other surgically-treated diseases. Ideal treatment of pilonidal sinus should be conducted in outpatient settings under local anesthesia, have less postoperative pain, fast recovery, high success rates, and low costs. Retrieved manuscripts concerning the utility of fibrin sealant in pilonidal disease were reviewed by the authors, and the data were extracted using a standardized collection tool.

This review suggests that fibrin sealant can be used for three purposes; (1) to obliterate the dead space under a closed wound; (2) to cover an open wound; (3) for primary treatment of sinus tracts in which they are filled with the sealant.

The fibrin sealant is composed of two ingredients; human fibrinogen and bovine thrombin. When the two of these are combined, the thrombin converts the fibrinogen into fibrin in less than a minute. This 3 dimensional fibrin plug is used as a haemostatic or a sealing agent.

In this systematic review, the authors have presented a thorough and critical analysis of the utility of fibrin sealant for the treatment of pilonidal disease as a minimally invasive method.

P- Reviewer: Berna A, Klinge U S- Editor: Qiu S L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Hull TL, Wu J. Pilonidal disease. Surg Clin North Am. 2002;82:1169-1185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5:13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4895] [Cited by in RCA: 6890] [Article Influence: 344.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kayaalp C. Basic calculating errors in systematic reviews. Obes Surg. 2013;23:1673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Greenberg R, Kashtan H, Skornik Y, Werbin N. Treatment of pilonidal sinus disease using fibrin glue as a sealant. Tech Coloproctol. 2004;8:95-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lund JN, Leveson SH. Fibrin glue in the treatment of pilonidal sinus: results of a pilot study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1094-1096. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Seleem MI, Al-Hashemy AM. Management of pilonidal sinus using fibrin glue: a new concept and preliminary experience. Colorectal Dis. 2005;7:319-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Patti R, Angileri M, Migliore G, Sparancello M, Termine S, Crivello F, Gioè FP, Di Vita G. Use of fibrin glue in the treatment of pilonidal sinus disease: a pilot study. G Chir. 2006;27:331-334. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Altinli E, Koksal N, Onur E, Celik A, Sumer A. Impact of fibrin sealant on Limberg flap technique: results of a randomized controlled trial. Tech Coloproctol. 2007;11:22-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sözen S, Emir S, Güzel K, Ozdemir CS. Are postoperative drains necessary with the Karydakis flap for treatment of pilonidal sinus? (Can fibrin glue be replaced to drains?) A prospective randomized trial. Ir J Med Sci. 2011;180:479-482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Elsey E, Lund JN. Fibrin glue in the treatment for pilonidal sinus: high patient satisfaction and rapid return to normal activities. Tech Coloproctol. 2013;17:101-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Isik A, Eryılmaz R, Okan I, Dasiran F, Firat D, Idiz O, Sahin M. The use of fibrin glue without surgery in the treatment of pilonidal sinus disease. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7:1047-1051. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Smith CM, Jones A, Dass D, Murthi G, Lindley R. Early experience of the use of fibrin sealant in the management of children with pilonidal sinus disease. J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50:320-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bergel S. Uber Wirkungen des Fibrins. Deutsch Wochenschr. 1909;35:633-665. |

| 14. | Pertici V, Laurin J, Marqueste T, Decherchi P. Comparison of a collagen membrane versus a fibrin sealant after a peroneal nerve section and repair: a functional and histological study. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2014;156:1577-1590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 274] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Spotnitz WD. Fibrin sealant: past, present, and future: a brief review. World J Surg. 2010;34:632-634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Emir S, Bali İ, Sözen S, Yazar FM, Kanat BH, Gürdal SÖ, Özkan Z. The efficacy of fibrin glue to control hemorrhage from the gallbladder bed during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ulus Cerrahi Derg. 2013;29:158-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kayaalp C, Aydin C. Review of phenol treatment in sacrococcygeal pilonidal disease. Tech Coloproctol. 2009;13:189-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sajid MS, Hutson KH, Rapisarda IF, Bonomi R. Fibrin glue instillation under skin flaps to prevent seroma-related morbidity following breast and axillary surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;5:CD009557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Cha HG, Kang SG, Shin HS, Kang MS, Nam SM. Does fibrin sealant reduce seroma after immediate breast reconstruction utilizing a latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap? Arch Plast Surg. 2012;39:504-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kayaalp C, Olmez A, Aydin C, Piskin T. Tumescent local anesthesia for excision and flap procedures in treatment of pilonidal disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1780-1783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kayaalp C, Olmez A, Aydin C, Piskin T, Kahraman L. Investigation of a one-time phenol application for pilonidal disease. Med Princ Pract. 2010;19:212-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Olmez A, Kayaalp C, Aydin C. Treatment of pilonidal disease by combination of pit excision and phenol application. Tech Coloproctol. 2013;17:201-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Handmer M. Sticking to the facts: a systematic review of fibrin glue for pilonidal disease. ANZ J Surg. 2012;82:221-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |