Published online Aug 27, 2025. doi: 10.4240/wjgs.v17.i8.104474

Revised: April 27, 2025

Accepted: June 23, 2025

Published online: August 27, 2025

Processing time: 166 Days and 4.8 Hours

Cardiovascular (CV) complications are common in intensive care unit (ICU) patients after gastrointestinal surgery and are associated with increased mortality and prolonged hospital stay. The optimization of postoperative nursing inter

To investigate the effects of enhanced recovery nursing on CV complications after gastrointestinal surgery in ICU patients and associated risk factors.

A retrospective analysis was conducted on 78 adult patients who underwent gastrointestinal surgery in the ICU of our hospital between February 2023 and September 2024. Among them, 40 patients received standard care (control group), while 38 received enhanced recovery nursing (observation group). We compared the incidence of CV complications and nursing satisfaction between the two groups. Patients were divided into CV complication and non-complication groups based on complication occurrence, and logistic regression analysis was used to identify risk factors.

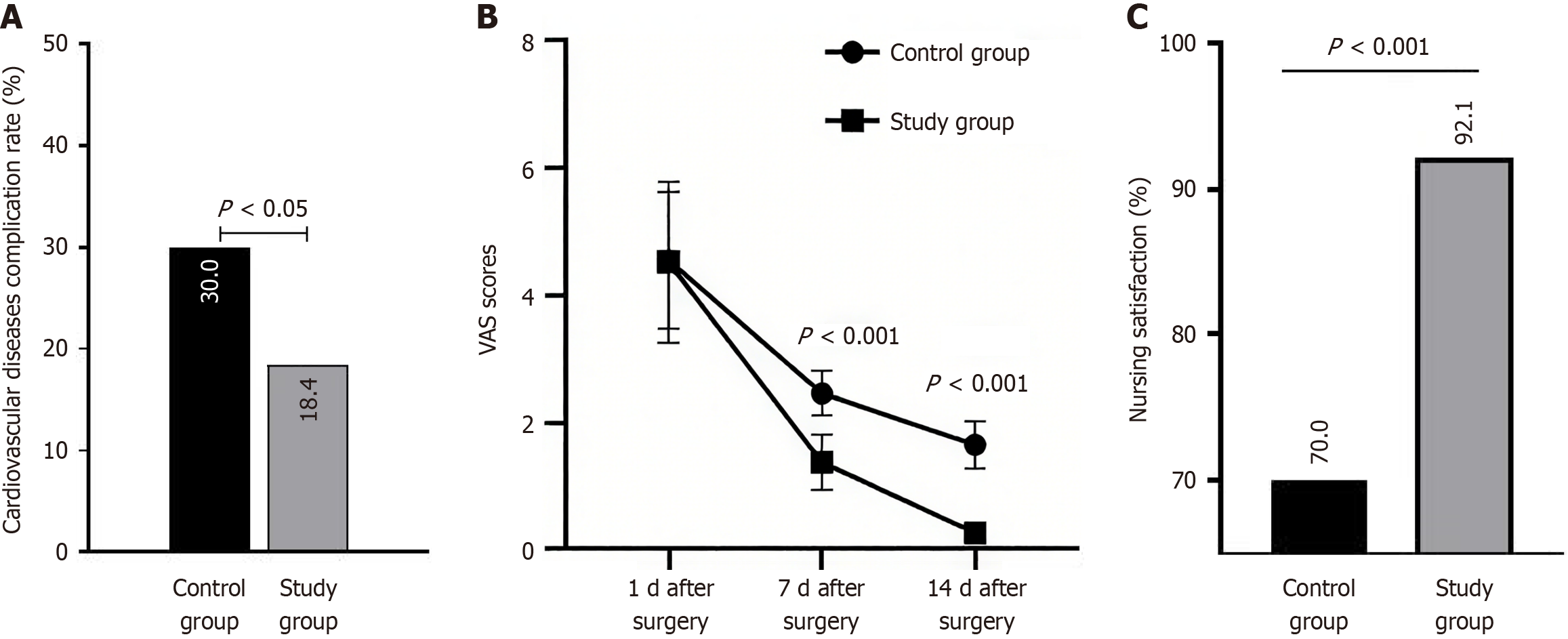

In the control and observation groups, the incidence of CV complications was 30.0% (12/40) and 18.4% (7/38), with a nursing satisfaction rate of 70.0% (28/40) and 92.1% (35/38), respectively. The postoperative pain score at 14 days was significantly lower in the observation group (0.27 ± 0.15) compared to the control group (1.65 ± 0.37), with all differences being statistically significant (P < 0.05). Univariate analysis indicated significant differences in age, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes, smoking history, history of heart failure, and previous myocardial infarction (P < 0.05). Multivariate logistic regression identified heart failure history, previous myocardial infarction, age, hypertension, and diabetes as independent risk factors, with odds ratios of 1.195, 1.528, 1.062, 1.836, and 1.942, respectively (all P < 0.05).

Implementing enhanced recovery nursing for ICU patients after gastrointestinal surgery is beneficial in reducing the incidence of CV complications and improving nursing satisfaction.

Core Tip: Cardiovascular (CV) complications are common in intensive care unit (ICU) patients post-gastrointestinal surgery, leading to higher mortality and longer hospital stays. This study highlights the benefits of enhanced recovery nursing in reducing these complications and improving nursing satisfaction. The results indicate that key independent predictors of CV complications include a history of heart failure, previous myocardial infarction, advanced age, hypertension, and diabetes. Optimizing postoperative nursing interventions, particularly in pain management, is essential for mitigating these risks in ICU patients.

- Citation: Wang L, Yang P, He XQ, Xia H. Nursing interventions’ impact on cardiovascular complications after gastrointestinal surgery in intensive care unit: Risk factor analysis. World J Gastrointest Surg 2025; 17(8): 104474

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-9366/full/v17/i8/104474.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4240/wjgs.v17.i8.104474

Gastrointestinal diseases are prevalent clinical conditions with a high incidence, and many patients require surgical intervention due to the severity of their conditions[1]. Surgical treatment frequently entails considerable physiological and psychological stress[2]. In particular, patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) who are recuperating from gastrointe

During gastrointestinal surgery, anesthetic stimulation and surgical trauma have been shown to inhibit gastrointestinal motility to a certain extent, resulting in postoperative symptoms such as abdominal distension, pain, and altered bowel movements[5]. These symptoms have been demonstrated to exert a detrimental effect on patients' physical and mental well-being and they can also result in various postoperative complications, severely affecting patients' quality of life[6]. A review of the extant literature reveals that the incidence of complications following gastrointestinal surgery has been documented to range from 10-30% in clinical studies[7]. Of these complications, cardiovascular (CV) complications are particularly severe and may include myocardial infarction, heart failure, and arrhythmias[7]. These complications further increase the risk of mortality and the healthcare burden on the system.

Consequently, the implementation of clinical nursing interventions assumes paramount importance in the context of gastrointestinal surgical interventions. Typically, patients receiving intensive care following gastrointestinal surgery are subject to conventional nursing interventions, which prioritize fundamental care components such as vital sign mo

As contemporary healthcare models undergo continuous evolution, the clinical demand for nursing has undergone a gradual shift from a myopic focus on disease treatment to an integrated model encompassing health maintenance, rehabilitation, and prevention[9]. The concept of enhanced recovery nursing has emerged in this context, originating in Europe and the United States in the 1990s. The emphasis on utilizing scientific methodologies prior to, during, and following surgical procedures aims to mitigate surgical stress responses, reduce the risk of complications, and accelerate postoperative recovery[10,11]. This approach involves a comprehensive assessment of the patient's condition, the development of personalized nursing plans, and enhanced rehabilitation training post-surgery. The efficacy of these interventions in positively impacting postoperative recovery and prognosis has been demonstrated through empirical evidence.

In recent years, China has gradually adopted the concept of enhanced recovery nursing for postoperative rehabilitation care for gastrointestinal diseases, achieving notable outcomes[12,13]. However, there remains a paucity of in-depth and systematic research on the specific effects of enhanced recovery nursing on CV complications in ICU patients following gastrointestinal surgery, as well as an analysis of the associated risk factors. Furthermore, by thoroughly analyzing the risk factors for CV complications in ICU patients’ post-gastrointestinal surgery, targeted measures can be implemented to reduce the risk of complications and improve clinical outcomes for patients.

This study aims to explore the impact of enhanced recovery nursing on CV complications after gastrointestinal surgery in ICU patients and to analyze related risk factors, with a view to providing strong support for optimizing nursing strategies and improving the quality of postoperative recovery in ICU patients after gastrointestinal surgery.

This study retrospectively selected the clinical data of 78 adult patients who underwent gastrointestinal surgery in the ICU of our hospital from February 2023 to September 2024. The study population included 40 patients receiving conventional care, who were assigned to the control group, and 38 patients receiving enhanced recovery nursing, who were assigned to the observation group. The incidence of CV complications and nursing satisfaction between the two groups were compared. Based on the occurrence of CV complications, patients were divided into the CV complications group and the non-CV complications group, and data were collected for logistic regression analysis to determine the risk factors for CV complications. Given the retrospective nature of the study, a formal sample size calculation was not conducted. The study adhered to institutional privacy and security policies to ensure the protection and security of patient data during data sourcing, cleansing, scrubbing, normalization, and acquisition.

This study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of our hospital and was conducted by the principles of the Helsinki Declaration.

Inclusion criteria[14]: (1) Underwent gastrointestinal surgery in the ICU; (2) Diagnosed with colorectal cancer, gastric cancer, or rectal cancer; and (3) Normal consciousness, mental status, and communication ability.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Poor compliance with nursing; (2) Coagulation disorders; (3) Severe major organ dysfunction; (4) Received preoperative chemotherapy or radiotherapy; and (5) Gastrointestinal obstruction.

Control group: The control group implemented conventional nursing[15]: (1) Preoperative assessment: Evaluate the patient's general condition, specialty status, psychological state, nutritional status, and potential complications. Specialty assessment includes checking for abdominal masses, tenderness, distension, acid reflux, loss of appetite, and other gastrointestinal symptoms; (2) Preoperative care: Timely alleviate the patient's negative emotions, answer questions, and explain the surgical methods and precautions. Complete routine checks, coagulation function tests, assessments of major organ functions, and specialized examinations such as gastrointestinal endoscopy and abdominal computed tomography. Instruct patients to avoid gas-producing foods for 2 days before surgery, switch to a liquid diet 1 day before surgery, fast for 12 hours before surgery, and restrict water intake for 4-6 hours before surgery. Prepare for routine preoperative preparations such as skin preparation and blood preparation. For laparoscopic surgery patients, ensure the cleanliness of the umbilical incision. Administer antibiotics orally according to individual circumstances 3 days before surgery, and perform a cleansing enema on the morning of the surgery or the day before; (3) Intraoperative care: Assist the surgical team with drainage, suturing, and other procedures, and adjust the operating room's temperature and humidity; and (4) Postoperative care: Closely monitor the patient's vital signs, and provide routine pain relief, dietary guidance, and rehabilitation training. Ensure nutritional support after surgery, observe the patient's consciousness, and check for dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, or gastrointestinal reactions. Regularly test blood lipids, blood glucose, and liver and kidney functions. Monitor for complications such as nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain, and provide symptomatic treatment promptly.

Observation group: The observation group implemented enhanced recovery nursing[16]: (1) Preoperative care: (a) Pre

CV complications[17]: This includes new-onset severe arrhythmias, recurrent angina, recurrent heart failure, repeat revascularization, in-stent stenosis, myocardial infarction, and cardiogenic death.

Postoperative pain scores[18]: The Visual Analog Scale (VAS) is used to assess pain, with scores categorized as follows: 0 indicates no pain, 1-3 represents mild pain, 4-6 indicates moderate pain, 7-9 signifies severe pain, and 10 denotes unbearable severe pain.

Nursing satisfaction[19]: This study observed and compared nursing satisfaction levels. A nursing satisfaction qu

Identification of risk factors for CV complications: Logistic regression analysis will be used to determine the risk factors associated with CV complications.

Statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics software, version 26.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). Descriptive statistics were expressed as means and standard deviations for continuous variables, while categorical variables were expressed as counts and percentages. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs) were used to evaluate risk factors impacting CV complications. The study subjects were divided into two groups based on the occurrence of CV complications, and factors with P < 0.05 from the univariate analysis were included in the multifactorial logistic regression analysis using the forward method. A two-tailed P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Control group: 26 males and 14 females; Age 27-75 years old; Mean 69.18 ± 5.32 years old; Types of surgery: Rectal surgery in 10 cases, colon surgery in 12 cases, stomach surgery in 16 cases. Observation group: 24 males and 14 females; Mean 67.35 ± 4.76 years old; Types of surgery: Rectal surgery 11 cases, colon surgery 12 cases, stomach surgery 17 cases. After statistical analysis, there was no significant difference in baseline data between the two groups (P > 0.05), which was comparable.

After the nursing intervention, the incidence of overall CV complications in 78 patients was 24.3% (19/78). Among them, CV complications occurred in 30.0% of patients in the control group (12/40) and 18.4% of patients in the study group (7/38). The overall incidence of CV complications in the control group was significantly higher than that in the observation group (P = 0.035). As shown in Figure 1A.

Of the 19 patients who developed CV complications, there were 10 cases of severe arrhythmia (52.63%), 3 cases of angina pectoris (15.79%), 2 cases of heart failure (10.53%), 1 case of revascularization (5.26%), 1 case of stent stenosis (5.26%), 1 case of myocardial infarction (5.26%) and 1 case of cardiac death (5.26%). As shown in Table 1.

| Cardiovascular diseases | n (%) |

| Severe arrhythmia | 10 (52.63) |

| Angina pectoris | 3 (15.79) |

| Heart failure | 2 (10.53) |

| Revascularization | 1 (5.26) |

| Stent stenosis | 1 (5.26) |

| Myocardial infarction | 1 (5.26) |

| Cardiac death | 1 (5.26) |

Before the nursing intervention, the pain score of gastrointestinal surgery patients in the observation group was 4.52 ± 1.26 points, and there was no statistically significant difference compared with the control group (4.55 ± 1.07) points (P = 0.909). Pain scores (1.38 ± 0.43) and (0.27 ± 0.15) on 7 days and 14 days after surgery were lower than those of the control group (2.46 ± 0.35) and (1.65 ± 0.37), with statistical significance (P < 0.001), as shown in Figure 1B.

The nursing satisfaction score of patients in the observation group was 92.10% (35/38), which was significantly higher than that of the control group [70.00% (28/40)], and the difference was statistically significant (P < 0.001), as shown in Figure 1C.

After the nursing intervention, 19 patients with CV complications were in the CV complications group, and 59 patients without CV complications were in the non- CV complications group. Univariate analysis showed that there were significant differences in age, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes, smoking history, heart failure history, and previous history of myocardial infarction (all P < 0.05; Table 2).

| Variables | Cardiovascular diseases, n = 19 | Non-cardiovascular diseases, n = 59 | P value |

| Age (mean ± SD, years) | 78.3 ± 4.2 | 57.5 ± 3.9 | < 0.001 |

| Sex (%) | 0.215 | ||

| Male | 12 (63.2) | 38 (64.4) | |

| Female | 7 (36.8) | 21 (35.6) | |

| BMI (mean ± SD, kg/m2) | 24.5 ± 3.0 | 21.9 ± 3.2 | 0.045 |

| ASA score [n (%)] | 0.253 | ||

| I-II | 9 (47.3) | 26 (44.1) | |

| III-IV | 10 (52.6) | 33 (55.9) | |

| History of smoking [n (%)] | 9 (47.3) | 12 (20.3) | < 0.001 |

| History of diabetes mellitus [n (%)] | 13 (68.4) | 24 (40.6) | < 0.001 |

| History of hypertension [n (%)] | 15 (78.9) | 25 (42.4) | < 0.001 |

| History of heart failure [n (%)] | 7 (36.8) | 6 (2.3) | 0.043 |

| History of myocardial infarction [n (%)] | 5 (26.3) | 5 (8.4) | 0.008 |

With CV complications as the dependent variable (0 = no, 1 = yes), according to the univariate analysis results in Table 2, variables with statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) were analyzed by Logistic regression for independent risk factors affecting CV complications.

The results showed that the Diabetes history is the risk of CV complications (OR = 1.942, 95%CI: 1.826-2.139). A history of heart failure is a risk factor for CV complications (OR = 1.195, 95%CI: 1.141-1.326), and a history of hypertension is also a risk factor for CV complications (OR = 1.836, 95%CI: 1.517-2.592). Age is a risk factor for CV complications (OR = 1.062; 95%CI: 1.035-1.089); History of myocardial infarction is also a risk factor for CV complications (OR = 1.528; 95%CI: 1.456-1.872). As shown in Table 3, P < 0.05.

| Variable | Reference | P value | OR | 95%CI |

| History of myocardial infarction | ||||

| Yes | No | < 0.001 | 1.528 | 1.456-1.872 |

| History of heart failure | ||||

| Yes | No | 0.028 | 1.195 | 1.141-1.326 |

| Age ≥ 60, years | < 60 | < 0.001 | 1.062 | 1.035-1.089 |

| History of hypertension | ||||

| Yes | No | < 0.001 | 1.836 | 1.517-2.592 |

| Diabetes history | ||||

| Yes | No | 0.017 | 1.942 | 1.825-2.136 |

With the continuous advancement of surgical techniques, the management of postoperative complications has become increasingly important. Enhanced recovery nursing, as an emerging nursing model, emphasizes multidisciplinary colla

In this study, the incidence of CV complications in the observation group was 18.4%, while in the control group, it was 30.0%, with a statistically significant difference (P = 0.035). This result aligns with existing literature, suggesting that enhanced recovery nursing may improve patient outcomes by optimizing postoperative management and reducing the incidence of complications[21,22]. Enhanced recovery nursing emphasizes multidisciplinary collaboration, early mo

The nursing satisfaction in the observation group was 92.10%, significantly higher than the control group’s 70.00% (P < 0.001). This result suggests that enhanced recovery nursing can significantly improve overall patient satisfaction, likely due to more personalized care, timely pain management, and better communication provided to patients post-surgery. The increase in nursing satisfaction not only contributes to patients' psychological well-being but may also influence their postoperative recovery speed and quality of life[24].

Both univariate analysis and logistic regression analysis revealed that a history of diabetes, heart failure, hypertension, age, and previous myocardial infarction were independent risk factors for CV complications. This is consistent with existing research, highlighting the importance of these factors in postoperative CV risk assessment[25,26]. Notably, patients with diabetes and hypertension have a significantly increased risk of CV complications, indicating that closer monitoring and management of these high-risk patients is crucial in clinical practice. Additionally, advancing age was positively correlated with the risk of CV complications, suggesting that CV health management should be prioritized in elderly patients.

Based on the risk factors identified in this study, it is crucial to develop personalized interventions for high-risk patients. For example, specialized monitoring and management programs can be implemented for patients with diabetes and hypertension to ensure early identification and management of potential CV risks. Furthermore, hospitals should address potential implementation barriers, such as resource limitations and inadequate staff training, by taking effective intervention measures, such as introducing multidisciplinary teamwork and enhancing nursing training, thereby promoting the implementation of enhanced recovery nursing in clinical practice.

The results of this study indicate that enhanced recovery nursing can effectively reduce the incidence of CV complications in ICU patients following gastrointestinal surgery and improve nursing satisfaction. A history of diabetes, heart failure, hypertension, age, and previous myocardial infarction are significant risk factors for CV complications. Screening for risk factors should be prioritized before surgery to identify high-risk patients for targeted interventions, including intensive glycemic control (maintaining HbA1c < 7% for diabetics), optimization of blood pressure (targeting systolic < 140 mmHg), and adjustment of cardioprotective medications. Enhanced recovery care protocols should feature dynamic risk monitoring, like using wearable devices to track hemodynamic stability in older patients and implementing nurse-led delirium prevention bundles. Multidisciplinary teams must work together to address modifiable risks by encouraging early postoperative mobilization for hypertensive patients and structured fluid management for those with heart failure histories. By translating these evidence-based strategies into standardized clinical pathways, providers can proactively reduce CV risk and improve surgical outcomes in high-risk populations.

| 1. | Li X, Liu S, Liu H, Zhu JJ. Acupuncture for gastrointestinal diseases. Anat Rec (Hoboken). 2023;306:2997-3005. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Magoon R, Puri S, Bandyopadhyay A. Gastrointestinal complications from a cardiac surgical perspective. Aust Crit Care. 2024;37:842. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chor CYT, Mahmood S, Khan IH, Shirke M, Harky A. Gastrointestinal complications following cardiac surgery. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2020;28:621-632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Vanstone MG, Krewulak K, Taneja S, Swinton M, Fiest K, Burns KEA, Debigare S, Dionne JC, Guyatt G, Marshall JC, Muscedere JG, Deane AM, Finfer S, Myburgh JA, Gouskos A, Rochwerg B, Ball I, Mele T, Niven DJ, English SW, Verhovsek M, Cook DJ; Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. Patient-important upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the ICU: A mixed-methods study of patient and family perspectives. J Crit Care. 2024;81:154761. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lundberg RK, Elftmann AE, Wilson SD, Gamblin TC. The Connell Stitch: A Two-Generation Contribution to Gastrointestinal Surgery. Am Surg. 2023;89:6449-6451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cook DJ, Swinton M, Krewulak KD, Fiest K, Dionne J, Debigare S, Guyatt G, Taneja S, Alhazzani W, Burns KEA, Marshall JC, Muscedere J, Gouskos A, Finfer S, Deane AM, Myburgh J, Rochwerg B, Ball I, Mele T, Niven D, English S, Verhovsek M, Vanstone M. What counts as patient-important upper gastrointestinal bleeding in the ICU? A mixed-methods study protocol of patient and family perspectives. BMJ Open. 2023;13:e070966. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lin S, Kühn F, Schiergens TS, Zamyatnin AA Jr, Isayev O, Gasimov E, Werner J, Li Y, Bazhin AV. Experimental postoperative ileus: is Th2 immune response involved? Int J Med Sci. 2021;18:3014-3025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Huang D, Li Y, Ye J, Liu C, Shen D, Lv Y. Different nursing interventions on sleep quality among critically ill patients: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023;102:e36298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Toews I, George AT, Peter JV, Kirubakaran R, Fontes LES, Ezekiel JPB, Meerpohl JJ. Interventions for preventing upper gastrointestinal bleeding in people admitted to intensive care units. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;6:CD008687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wang C, Tan B, Qian Q. The impact of perioperative enhanced recovery nursing model on postoperative delirium and rehabilitation quality in elderly patients with femoral neck fractures. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2023;24:947. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hu Z, Li D. The Effect of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Nursing on the Recovery in Patients After Liver Transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2024;56:1617-1623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zhang L, Wu Q, Wang X, Zhu X, Shi Y, Wu CJ. Factors impacting early mobilization according to the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery guideline following gastrointestinal surgery: A prospective study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2024;24:234-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hu J, Zhang X, Sun J, Hu H, Tang C, Ba L, Xu Q. Supportive Care Needs of Patients With Temporary Ostomy in Enhanced Recovery After Surgery: A Mixed-Methods Study. J Nurs Res. 2024;32:e329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Piwowarczyk P, Kutnik P, Borys M, Rypulak E, Potręć-Studzińska B, Sysiak-Sławecka J, Czarnik T, Czuczwar M. Influence of Early versus Late supplemental ParenteraL Nutrition on long-term quality of life in ICU patients after gastrointestinal oncological surgery (hELPLiNe): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2019;20:777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hsiao WL, Hung WT, Yang CH, Lai YH, Kuo SW, Liao HC. Effects of high flow nasal cannula following minimally invasive esophagectomy in ICU patients: A prospective pre-post study. J Formos Med Assoc. 2023;122:1247-1254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Brown ML, Simpson V, Clark AB, Matossian MD, Holman SL, Jernigan AM, Scheib SA, Shank J, Key A, Chapple AG, Kelly E, Nair N. ERAS implementation in an urban patient population undergoing gynecologic surgery. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2022;85:1-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kirmani TA, Singh M, Kumar S, Kumar K, Parkash O, Sagar, Yasmin F, Khan F, Chughtai N, Asghar MS. Plasma random glucose levels at hospital admission predicting worse outcomes in STEMI patients undergoing PCI: A case series. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2022;78:103857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Delgado DA, Lambert BS, Boutris N, McCulloch PC, Robbins AB, Moreno MR, Harris JD. Validation of Digital Visual Analog Scale Pain Scoring With a Traditional Paper-based Visual Analog Scale in Adults. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev. 2018;2:e088. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 394] [Article Influence: 56.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zhang M, Li X, Bai Y. Prone position nursing combined with ECMO intervention prevent patients with severe pneumonia from complications and improve cardiopulmonary function. Am J Transl Res. 2021;13:4969-4977. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Pinho B, Costa A. Impact of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) guidelines implementation in cesarean delivery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2024;292:201-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Turan Z, Topaloglu M, Ozyemisci Taskiran O. Is tele-rehabilitation superior to home exercise program in COVID-19 survivors following discharge from intensive care unit? - A study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. Physiother Res Int. 2021;26:e1920. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Chang SC, Lai JI, Lu MC, Lin KH, Wang WS, Lo SS, Lai YC. Reduction in the incidence of pneumonia in elderly patients after hip fracture surgery: An inpatient pulmonary rehabilitation program. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e11845. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Pang Y, Li H, Zhao L, Zhang C. An Established Early Rehabilitation Therapy Demonstrating Higher Efficacy and Safety for Care of Intensive Care Unit Patients. Med Sci Monit. 2019;25:7052-7058. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Yagi M, Morita K, Matsui H, Michihata N, Fushimi K, Koyama T, Fujitani J, Yasunaga H. Outcomes After Intensive Rehabilitation for Mechanically Ventilated Patients: A Nationwide Retrospective Cohort Study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2021;102:280-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Tsai IT, Wang CP, Lu YC, Hung WC, Wu CC, Lu LF, Chung FM, Hsu CC, Lee YJ, Yu TH. The burden of major adverse cardiac events in patients with coronary artery disease. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2017;17:1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Salinero-Fort MA, Andrés-Rebollo FJS, Cárdenas-Valladolid J, Méndez-Bailón M, Chico-Moraleja RM, de Santa Pau EC, Jiménez-Trujillo I, Gómez-Campelo I, de Burgos Lunar C, de Miguel-Yanes JM; MADIABETES. Cardiovascular risk factors associated with acute myocardial infarction and stroke in the MADIABETES cohort. Sci Rep. 2021;11:15245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |